Herman Melville’s The Piazza has many mythological and theological referrals scattered throughout its pages. Greek mythology terms such as Elysium, Orion, and Damocles are intertwined with biblical references of Abraham, Lazarus, and the Kaaba (Holy Stone), among many others. These parabled sources spoke to the readers of his era in descriptors that would be easily recognizable and understandable. Melville’s conscious mixing of the two religious forms, showing more than one ideological opinion, is reminiscent of another author he was known to look to for inspiration, Plutarch (as spoken about in several commentary excerpts found in Melville’s Marginalia). Greek by birth, Plutarch integrated into Roman society in the middle part of his life, even changing his name to Lucius Plutarchus, and was witness to Roman acceptance of multiple forms of religion. Although Christianity was not accepted in Rome for another three and a half centuries, the well-rounded structure of the Roman society of Plutarch’s time was no doubt an influence on his work, and subsequently, on Melville. It is quite possible that some of the conscious or unconscious blending of these biblical and mythical concepts also came from Melville’s reading of Dante, translated by Rev. Henry Francis Cary, one of many books found in the Melville collection on the “Melville’s Marginalia” website.<br>

Melville filled the pages of the Piazza with allusion, many of which can be lost on the modern reader. One such reference this contemporary reader may not readily connect to is Abraham. For Melville, this citation is most likely drawn from The New Testament of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ: Translated out of the Original Greek, and The Book of Psalms: Translated out of the Original Hebrew, published by the American Bible Society, New York, 1844, Book of John, pg. 171. A book found in Melville’s personal collection.<br>

The Piazza quote where we first find mention of Abraham “And then, in the cool elysium of my northern bower, I, Lazarus in Abraham's bosom, cast down the hill a pitying glance on poor old Dives, tormented in the purgatory of his piazza to the south.”(Pg. 2), is a striking reference to the biblical ideal mixing of Greek Mythology and the Jewish faith. This entire idiom can be quite puzzling to the unknowing reviewer of Melville’s work. The belief is that Abraham is the father of all Jews, with all faithful Jews being called the sons and daughters of Abraham. They are promised that Abraham will be there to meet them when they pass away.

The first part of the quote “I, Lazarus in Abraham's bosom,” is a reference to the story of Lazarus found in the Book of John 11, where Lazarus comes down with an illness and passes away (resting in the bosom of Abraham), until the fourth day of his passing, when Jesus visits his tomb and Lazarus is resurrected.

Elysium is a common Greek citation alluded to in describing a heavenly destination for those who were heroes or lived virtuous and courageous lives. In Greek mythology, interestingly, the term refers to two ideally similar, yet geographically different, locales. The first of the two backdrops is an island paradise (Island of the Blessed), surrounded by a river, reigned over by Kronos, the son of Zeus. The second location was found in the underworld kingdom of Haides (or Hades), where it’s pleasing meadows were separated from Hell, also by a river. The river itself has held several names throughout the many reincarnations of the ancient concept, being known as Okeanos, or Lethe, but is best recognized and remembered as the river Styx. This place, Elysium, is the piazza Melville refers to where his narrator (Melville’s version of Lazarus) looks down from his heavenly perch upon the supposedly rich person of the town, left to suffer his poor views from his self-imposed hell.<br>

The acknowledgment of “poor old Dives” is yet another harkening to the story of Lazarus. The biblical man, nicknamed Dives, was a rich man who did not offer any assistance to the hungry and sick Lazarus, and upon both men’s passing (which were close in interval to one another), Dives looked up from his sweltering confines in Hades (later renamed by the Catholic faith as purgatory) to see Lazarus in comfort at the side of Abraham, in Elysium.<br>

It is of interest to note, on page 10 of The Piazza, a point of view change for the narrator. Instead of continuing to cast or see himself as Lazarus, the storyteller now shows the opposite human qualities of Poor Old Dives, referenced in the earlier quote from the story. This contrast could be Melville’s way of showing the hypocrisy inherently found in all humans. Melville’s orator denies the impoverished girl of the knowledge as to his true identity, and with this action, or inaction, also denies himself the ability to help relieve her misery. This could be a possible nod to tendencies of the intrinsic need for self-preservation being held in highest regard, whether we are consciously aware of it or not, and despite our supposed best intentions, morals, and values.

Once, and if, the present-day reader is capable of deciphering Melville’s intimations, the underlying story of The Piazza becomes clearer. One of the biggest obstacles to reading classical works is understanding the author’s frame of reference. This inclination of recognizing the era in which a work was produced is often lost on the casual reader. Because of this, the writing (or alternative forms of art being studied) is frequently discarded based on lack of knowledge and understanding of its outdated references and allusions.<br>

Through researching the terminology Melville used in the earlier quoted text, the reader is better able to relate to the idea, or message, behind the allusions. This analysis and interpretation, although complex and inconvenient at times, can open (for both the researcher and modern reader), countless windows to more well-rounded and higher levels of learning.<br>

Researching this small quote from The Piazza allowed me to gain a much better perspective and appreciation of the entire text. This recognition is not only for the writing itself, or for the allusions used, which help the reviewer to envision the picture Melville has created, but for the arduous work ethic and passion which the modern examiner of these works must possess. My small foray into Melville’s world was mesmerizing. Looking through the actual library of his favorite texts, most being used in some form or other, to bolster his own writing, was for me, like seeing into the author’s mind. Melville’s annotations in several of the texts were a great insight into his personal character and beliefs. The intrinsic insights of Melville left behind in the pages of all these now classic works were also an interesting way for someone like me to see how an accomplished writer such as Melville looked at (both revering and loathing) many of his contemporaries.

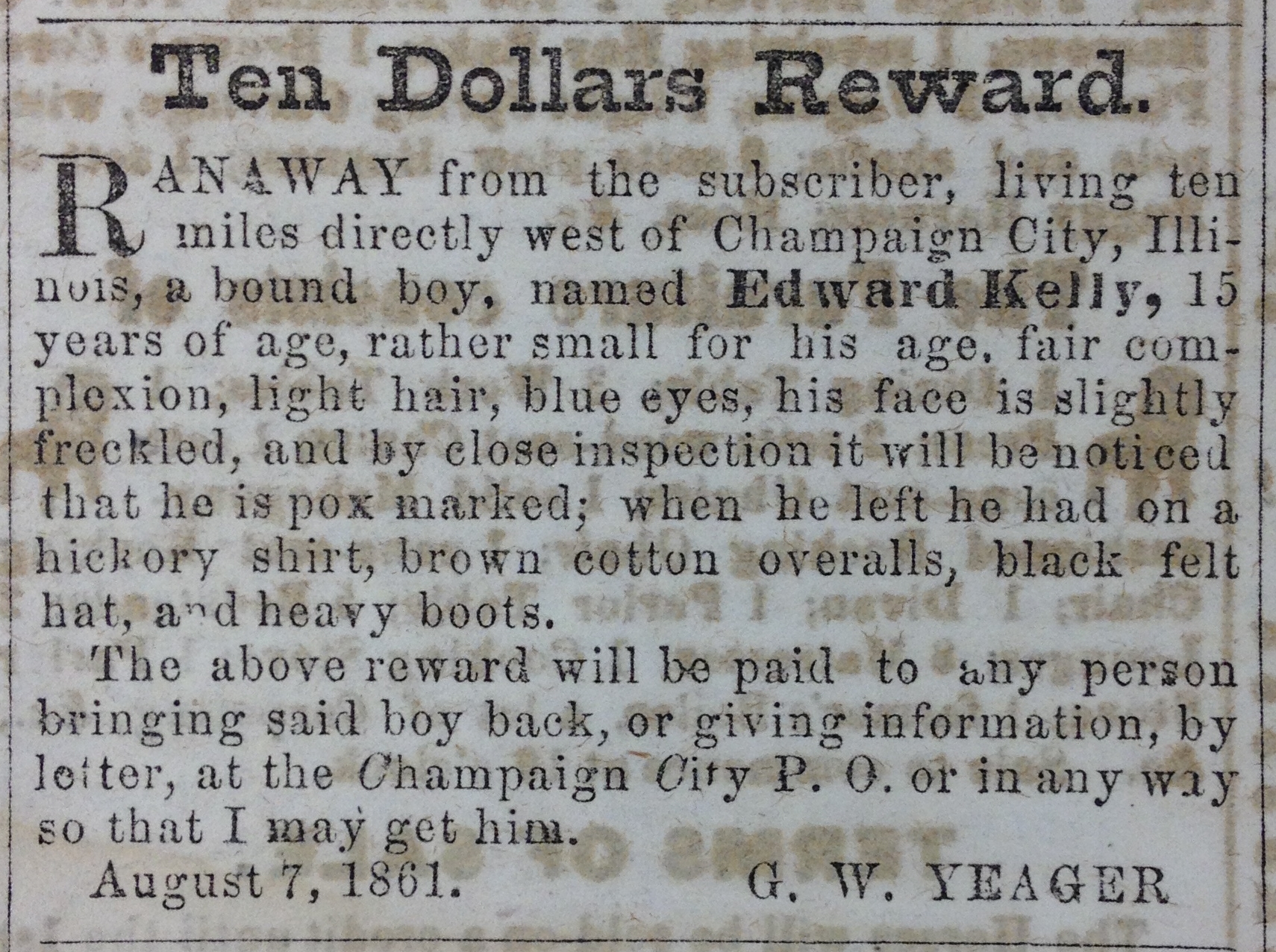

This artifact depicts the perceptions of many of those in society in the 19th century surrounding the problem of orphaned children. For instance, the image depicts a timeline of orphaned children, beginning with their life living on the streets, barefoot and sinister, followed by the picturesque notion of them heading out west on the orphan trains, and finally as upstanding young citizens, working for the farming families that had adopted them. This image is highly relevant to Herman Melville’s, “The Piazza,” in that Melville criticized the emigration program founded by Charles Loring Brace in 1855, with his characters Marianna and her brother, who he defines in “The Piazza,” as orphan children. Additionally, like Melville’s story revolving around Marianna and her brother, the picture paints idealistic notions about Brace’s emigration program, despite the reality that many of these children were not merely rescued orphans, but should be seen instead, as indentured servants. Both Melville and this image broach this subject, albeit in different forms. For instance, the image shows an orphaned boy plowing a field with the caption, “The Young Farmer.” Here, the idea of indentured servitude is depicted as an honorable and positive alternative to the life the orphans lived before being “placed-out” by Brace’s institution.

In opposition to this, Melville portrays the lives of young orphan boys in a different light. For example, in “The Piazza,” Melville writes that Marianna’s brother, “seven months back … only seventeen, had come hither, a long way from the other side, to cut wood and burn coal” and that one “evening, fagged out, he did come home, he soon left his bench, poor fellow, for his bed, just as one, at last, wearily quits that, too, for still deeper rest. The bench, the bed, the grave” (Melville). Additionally, Melville portrays the life of Marianna as one much different than images such as this one. For example, Melville writes that, Marianna wishes she “could rest like [him]; but [hers] is mostly but dull woman’s work- - sitting, sitting, restless sitting” (Melville). One can see the stark contrast between the different depictions of the orphaned children in the image and that of Melville’s. Despite Brace’s attempts to suggest his emigration program was beneficial to orphaned children, and the image’s attempt to glorify it as well, it’s clear that when one knows the truth, as Melville surely did, many of the adopted children who were sent out west, did not end up being strong, happy young men and women, but instead were merely indentured servants, forced to work for the families who took them in.

This artifact depicts the perceptions of many of those in society in the 19th century surrounding the problem of orphaned children. For instance, the image depicts a timeline of orphaned children, beginning with their life living on the streets, barefoot and sinister, followed by the picturesque notion of them heading out west on the orphan trains, and finally as upstanding young citizens, working for the farming families that had adopted them. This image is highly relevant to Herman Melville’s, “The Piazza,” in that Melville criticized the emigration program founded by Charles Loring Brace in 1855, with his characters Marianna and her brother, who he defines in “The Piazza,” as orphan children. Additionally, like Melville’s story revolving around Marianna and her brother, the picture paints idealistic notions about Brace’s emigration program, despite the reality that many of these children were not merely rescued orphans, but should be seen instead, as indentured servants. Both Melville and this image broach this subject, albeit in different forms. For instance, the image shows an orphaned boy plowing a field with the caption, “The Young Farmer.” Here, the idea of indentured servitude is depicted as an honorable and positive alternative to the life the orphans lived before being “placed-out” by Brace’s institution.

In opposition to this, Melville portrays the lives of young orphan boys in a different light. For example, in “The Piazza,” Melville writes that Marianna’s brother, “seven months back … only seventeen, had come hither, a long way from the other side, to cut wood and burn coal” and that one “evening, fagged out, he did come home, he soon left his bench, poor fellow, for his bed, just as one, at last, wearily quits that, too, for still deeper rest. The bench, the bed, the grave” (Melville). Additionally, Melville portrays the life of Marianna as one much different than images such as this one. For example, Melville writes that, Marianna wishes she “could rest like [him]; but [hers] is mostly but dull woman’s work- - sitting, sitting, restless sitting” (Melville). One can see the stark contrast between the different depictions of the orphaned children in the image and that of Melville’s. Despite Brace’s attempts to suggest his emigration program was beneficial to orphaned children, and the image’s attempt to glorify it as well, it’s clear that when one knows the truth, as Melville surely did, many of the adopted children who were sent out west, did not end up being strong, happy young men and women, but instead were merely indentured servants, forced to work for the families who took them in.