involve some hocus-pocus

Wood-cut image (1598) of Mathematician and Astronomer Johannes Kepler defending his mother, Katharina Kepler, who was accused of witchcraft by potion brewing. This potion was said to create an illness in the accuser.

involve some hocus-pocus

Wood-cut image (1598) of Mathematician and Astronomer Johannes Kepler defending his mother, Katharina Kepler, who was accused of witchcraft by potion brewing. This potion was said to create an illness in the accuser.

discourse of those Egyptian magicians

Egyptians often saw rhetoric as an important part of life. They viewed the ability to utilize speech efficiently as magical, and magic was speech based. Here, Thomasius is playing with this fact and allowing his audience to understand his use of rhetoric.

And the devil cannot bring about things that are self-contradicting either, because even the divine power, greater than all others, cannot bring about self-contradictory things.

From Matthew Hopkins' The Discovery of Witches, 1647.

"God suffers the Devill many times to doe much hurt, and the devill doth play many times the deluder and impostor with these Witches, in perswading them that they are the cause of such and such a murder wrought by him with their consents, when and indeed neither he nor they had any hand in it, as thus: We must needs argue, he is of a long standing, above 6000. yeers, then he must needs be the best Scholar in all knowledges of arts and tongues, & so have the best skill in Physicke, judgment in Physiognomie, and knowledge of what disease is reigning or predominant in this or that mans body, (and so for cattell too) by reason of his long experience. This subtile tempter knowing such a man lyable to some sudden disease, (as by experience I have found) as Plurisie, Imposthume, &c. he resorts to divers Witches; if they know the man, and seek to make a difference between the Witches and the party, it may be by telling them he hath threatned to have them very shortly searched, and so hanged for Witches, then they all consult with Satan to save themselves, and Satan stands ready prepared, with a What will you have me doe for you, my deare and nearest children, covenanted and compacted with me in my hellish league, and sealed with your blood, my delicate firebrand-darlings.

The Divells speech to the Witches. Oh thou (say they) that at the first didst promise to save us thy servants from any of out deadly enemies discovery, and didst promise to avenge and flay all those, we pleased, that did offend us; Murther that wretch suddenly who threatens the down-fall of your loyall subjects. He then promiseth to effect it. Next newes is heard the partie is dead, he comes to the witch, and gets a world of reverence, credence and respect for his power and activeness, when and indeed the disease kills the party, not the Witch, nor the Devill, (onely the Devill knew that such a disease was predominant) and the witch aggravates her damnation by her familiarity and consent to the Devill, and so comes likewise in compass of the Lawes. This is Satans usuall impostring and deluding, but not his constant course of proceeding, for he and the witch doe mischiefe too much. But I would that Magistrates and Jurats would a little examine witnesses when they heare witches confess such and such a murder, whether the party had not long time before, or at the time when the witch grew suspected, some disease or other predominant, which might cause that issue or effect of death."

crystal-gazers, exorcists, and conjurors

Gypsies in the Market by Hans Burgkmair, 1473-1531, Germany

Gypsies in the Market by Hans Burgkmair, 1473-1531, Germany

but sorcerers and witches only tried to commit them by their spells and deceit

The last witch burning in Germany took place in 1775, nearly 50 years after Thomasius' death. The "witch" on trial was Anna Maria Schwegelin. She was said to have freely confessed to Satanism

supernaturally induced diseases

From King James I Daemonologie, 1587

"This word of Sorcerie is a Latine worde, which is taken from casting of the lot, & therefore he that vseth it, is called Sortiarius à sorte. As to the word of Witchcraft, it is nothing but a proper name giuen in our language. The cause wherefore they were called sortiarij, proceeded of their practicques seeming to come of lot or chance: Such as the turning of the riddle: the knowing of the forme of prayers, or such like tokens: If a person diseased woulde liue or dye. And in generall, that name was giuen them for vsing of such charmes, and freites, as that Crafte teacheth them. Manie poynts of their craft and practicques are common [pg 032] betuixt the Magicians and them: for they serue both one Master, althought in diuerse fashions. And as I deuided the Necromancers, into two sorts, learned and vnlearned; so must I denie them in other two, riche and of better accompt, poore and of basser degree. These two degrees now of persones, that practises this craft, answers to the passions in them, which (I told you before) the Deuil vsed as meanes to intyse them to his seruice, for such of them as are in great miserie and pouertie, he allures to follow him, by promising vnto them greate riches, and worldlie commoditie."

Code of Criminal Law

From Malleus Maleficarum: Who are the Fit and Proper Judges in the Trial of Witches?, 1486.

"Again, the laws decree that clerics shall be corrected by their own Judges, and not by the temporal or secular Courts, because their crimes are considered to be purely ecclesiastical. But the crime of witches is partly civil and partly ecclesiastical, because they commit temporal harm and violate the faith; therefore it belongs to the Judges of both Courts to try, sentence, and punish them. This opinion is substantiated by the Authentics, where it is said: If it is an ecclesiastical crime needing ecclesiastical punishment and fine, it shall be tried by a Bishop who stands in favour with God, and not even the most illustrious Judges of the Province shall have a hand in it. And we do not wish the civil Judges to have any knowledge of such proceedings; for such matters must be examined ecclesiastically and the souls of the offenders must be corrected by ecclesiastical penalties, according to the sacred and divine rules which our laws worthily follow. So it is said. Therefore it follows that on the other hand a crime which is of a mixed nature must be tried and punished by both courts. We make our answer to all the above as follows. Our main object here is to show how, with God's pleasure, we Inquisitors of Upper Germany may be relieved of the duty of trying witches, and leave them to be punished by their own provincial Judges; and this because of the arduousness of the work: provided always that such a course shall in no way endanger the preservation of the faith and the salvation of souls. And therefore we engaged upon this work, that we might leave to the Judges themselves the methods of trying, judging and sentencing in such cases. Therefore in order to show that the Bishops can in many cases proceed against witches without the Inquisitors; although they cannot so proceed without the temporal and civil Judges in cases involving capital punishment; it is expedient that we set down the opinions of certain other Inquisitors in parts of Spain, and (saving always the reverence due to them), since we all belong to one and the same Order of Preachers, to refute them, so that each detail may be more clearly understood. Their opinion is, then, that all witches, diviners, necromancers, and in short all who practise any kind of divination, if they have once embraced and professed the Holy Faith, are liable to the Inquisitorial Court, as in the three cases noted in the beginning of the chapter, Multorum querela, in the decretals of Pope Clement concerning heresy; in which it says that neither must the Inquisitor proceed without the Bishop, nor the Bishop without the Inquisitor: although there are five other cases in which one may proceed without the other, as anyone who reads the chapter may see. But in one case it is definitively stated that one must not proceed without the other, and that is when the above diviners are to be considered as heretics. In the same category they place blasphemers, and those who in any way invoke devils, and those who are excommunicated and have contumaciously remained under the ban of excommunication for a whole year, either because of some matter concerning faith or, in certain circumstances, not on account of the faith; and they further include several other such offences. And by reason of this the authority of the Ordinary is weakened, since so many more burdens are placed upon us Inquisitors which we cannot safely bear in the sight of the terrible Judge who will demand from us a strict account of the duties imposed upon us."

beasts in various ways

The first use of the word "Witch" in Germany was in 1450, and it was rarely used in association with a trial. By 1532 the views of witches had change dramatically. Cases of witch-craft harming citizens became more pronounced. Of these cases it was not uncommon for the witch to have caused a hail-storm to ruin the victims crops or for the witch to have bewitched cattle or farm animals. While this impacted the citizens and the local society, this kind of witch-craft did not interested the courts.

a broomor a goa

From Howard William's The Superstitions of Witchcraft, 1865.

"They ride in sieves on the sea, on brooms, spits magically prepared; and by these modes of conveyance are borne, without trouble or loss of time, to their destination. By these means they attend the periodical sabbaths, the great meetings of the witch-tribe, where they assemble at stated times to do homage, to recount their services, and to receive the commands of their lord. They are held on the night between Friday and Saturday; and every year a grand sabbath is ordered for celebration on the Blocksberg mountains, for the night before the first day of May. In those famous mountains the obedient vassals congregate from all parts of Christendom—from Italy, Spain, Germany, France, England, and Scotland. A place where four roads meet, a rugged mountain range, or perhaps the neighbourhood of a secluded lake or some dark forest, is usually the spot selected for the meeting."

and so forth

confession

From Ann Foster's Trial Documents in Salem, Mass.,1692

"18 July 1692. Ann Foster Examined confesed that the devill in shape of a #[black] man apeared to her w'th Goody carier about six yeare since when they made her awitch & that she promised to serve the divill two yeares: upon w'ch the Divill promised her prosperity & many things but never performed it, that she & martha Carier did both ride on a stick or pole when they went to the witch meeting at Salem Village & that the stick broak: as they ware caried in the aire above the tops of the trees & they fell but she did hang fast about the neck of Goody Carier & ware presently at the vilage, that she was then much hurt of her Leg, she further saith that she hard some of the witches say that their was three hundred & five in the whole Country, & that they would ruin that place the Vilige, also saith ther was present at that metting two men besides mr Buroughs the minister & one of them had gray haire, she saith that she formerly frequented the publique metting to worship god. but the divill had such power over her that she could not profit there & that was her undoeing: she saith that above three or foure yeares agoe Martha Carier told her she would bewitch James Hobbs child to death & the child dyed in twenty four howers"

hat Jews

Practical Kabbalah is a sect of the Judaism in which the use of "white magic" is common place by more elite members of the church. However, within this belief system, mostly amulets and incantations are utilized in associations with the divine.

Rather, perhaps Thomasius is referring to the custom of abstaining from bread during Passover. This is physically symbolized by those of the Jewish faith throwing bread into the fire.

Who does not know that Gypsies can set fire to stables and barns and that nevertheless this does not cause injury?

(1552 image of the Romani people)

(1552 image of the Romani people)

Blocksberg [sabbat]

During the witch trials, a common accusation was that a witch had taken sabbath with the devil. Sabbaths were often perceived as meetings between witches, demons, and the devil in which the latter would examine witches and sorcerers for his mark. If his mark, described as a mark of pain, was not present, then the devil would proceed to mark them. In 1670, this accusation of attending a sabbath had been the cause of multiple women getting the death sentence.

However, King Louis XIV instead ruled that they be banished instead of being burnt at the stake. The parliament appealed once more for the condemned witches to be burned, stating, “It has been the general feeling of all nations that such criminals ought to be condemned to death, and all the ancients were of the same opinion.” However, King Louis held fast to his order of the witches’ punishment to be exile rather than that of death. This political event made a huge impact on how witch trials and accused sabbath attenders were viewed, as reflective in Thomasius’ clear opinion on the sabbath.

witch-master who inflicted this disease on the patient

Wittenberg

In Wittenburg, during the early 1500s, Martin Luther began his vocal and written renouncement against the Catholic Church as corrupt and inherently sinful due to the indulgences associated with the church.

Despite how enlightened Martin Luther hoped to portray his Protestant teaching, Luther was an advent believer in witch-hunts. His rhetoric influenced followers into fearing the sinful natures of neighbors, homeless, and outcasts. This would eventually help stoke the fire of fear against witches and "devil's whores", as Luther put it, within Germany.

Pharise

I hold that he is responsible for the first sinful fall of the first human beings (that is, original sin).

It is commonly believed that the serpent in the Garden of Eden, which led Eve and Adam to sin against God’s orders, was representative of the Devil. This moment in the Bible is what Thomasius is referring to:

3 Now the serpent was more subtil than any beast of the field which the Lord God had made. And he said unto the woman, Yea, hath God said, Ye shall not eat of every tree of the garden?

2 And the woman said unto the serpent, We may eat of the fruit of the trees of the garden:

3 But of the fruit of the tree which is in the midst of the garden, God hath said, Ye shall not eat of it, neither shall ye touch it, lest ye die.

4 And the serpent said unto the woman, Ye shall not surely die:

5 For God doth know that in the day ye eat thereof, then your eyes shall be opened, and ye shall be as gods, knowing good and evil.

6 And when the woman saw that the tree was good for food, and that it was pleasant to the eyes, and a tree to be desired to make one wise, she took of the fruit thereof, and did eat, and gave also unto her husband with her; and he did eat.

7 And the eyes of them both were opened, and they knew that they were naked; and they sewed fig leaves together, and made themselves aprons.

8 And they heard the voice of the Lord God walking in the garden in the cool of the day: and Adam and his wife hid themselves from the presence of the Lord God amongst the trees of the garden.

9 And the Lord God called unto Adam, and said unto him, Where art thou?

10 And he said, I heard thy voice in the garden, and I was afraid, because I was naked; and I hid myself.

11 And he said, Who told thee that thou wast naked? Hast thou eaten of the tree, whereof I commanded thee that thou shouldest not eat?

12 And the man said, The woman whom thou gavest to be with me, she gave me of the tree, and I did eat.

13 And the Lord God said unto the woman, What is this that thou hast done? And the woman said, The serpent beguiled me, and I did eat. (KJV)

However, within Genesis there is no specific mention of the Devil by name.

sleep [that is, sexual intercourse] with them,

In the Fifteenth century there were eighteen witch executioned in Augsburg, Germany alone during this time period. One of which is the case of Anna Ebeler, an elderly lying-in maid who was convicted for witchcraft in 1669. All her victims were infants under the age of six months and the new mothers to these children. During her interrogation, or torture, Ebeler confessed to having intercourse with the devil on multiple occasions. This portrayal of “marriage” to the devil is not uncommon during this time period. However, Thomasius refused to acknowledge these admittances. He could not believe that a being of divine nature, as the devil was, could or would be intimate with a mortal.

In the Fifteenth century there were eighteen witch executioned in Augsburg, Germany alone during this time period. One of which is the case of Anna Ebeler, an elderly lying-in maid who was convicted for witchcraft in 1669. All her victims were infants under the age of six months and the new mothers to these children. During her interrogation, or torture, Ebeler confessed to having intercourse with the devil on multiple occasions. This portrayal of “marriage” to the devil is not uncommon during this time period. However, Thomasius refused to acknowledge these admittances. He could not believe that a being of divine nature, as the devil was, could or would be intimate with a mortal.

that the devil has horns, claws, or talons,

Art from the Renaissance often portrayed the devil as a horned figure with claws. As a new concept during this time-period, due to the sudden interest in the devil and demons, inspiration was often taken from originally Pagan imagery. This can be seen in the similarity of “horned-gods”, like that of Cernunnos of Celtic origin, and the depiction of the devil in Knight, Death and the Devil by German artist Albrecht Dürer. Christian Thomasius understood the implications of this imagery, as the Bible gives no description of the devil, and rejects the concepts as kindling to the fire of fear.

Art from the Renaissance often portrayed the devil as a horned figure with claws. As a new concept during this time-period, due to the sudden interest in the devil and demons, inspiration was often taken from originally Pagan imagery. This can be seen in the similarity of “horned-gods”, like that of Cernunnos of Celtic origin, and the depiction of the devil in Knight, Death and the Devil by German artist Albrecht Dürer. Christian Thomasius understood the implications of this imagery, as the Bible gives no description of the devil, and rejects the concepts as kindling to the fire of fear.

crystal-gazers

Johann Georg Faust was a scientist, physician, astrologer, and magician during the early 1500’s in Germany. Folklore grew around him and his abilities during this time period as he toured through Germany reading horoscopes and crystals, until the 1530’s when he was denounced by the church as being in league with the devil. This accusation caused cities and villages to bar his entry. In 1540, Faust died due to one of his experiments exploding, which caused mutilations to his body. The church interpreted these wounds as representative that the devil was taking him back to hell. This death, and the attention garnered to him after his burial, immortalized Faust in Germany. Growing up with these stories, Christian Thomasius was no stranger to this type of supernatural which he acknowledges as not only plausible, but very real, despite his views on witchcraft.

Johann Georg Faust was a scientist, physician, astrologer, and magician during the early 1500’s in Germany. Folklore grew around him and his abilities during this time period as he toured through Germany reading horoscopes and crystals, until the 1530’s when he was denounced by the church as being in league with the devil. This accusation caused cities and villages to bar his entry. In 1540, Faust died due to one of his experiments exploding, which caused mutilations to his body. The church interpreted these wounds as representative that the devil was taking him back to hell. This death, and the attention garnered to him after his burial, immortalized Faust in Germany. Growing up with these stories, Christian Thomasius was no stranger to this type of supernatural which he acknowledges as not only plausible, but very real, despite his views on witchcraft.

since I was forced to learn

Although in English-speaking society, Christian Thomasius is a barely known advocator of ending the witch trials, within German society his name is often brought up as one of the founders of modern-day philosophy and politics. Part of his fame is due to his creation of the first successful public journals within a society which intellectuals often only spoke to other intellectuals. By doing this, Thomasius opened the door for something that was virtually unheard of, a conscious public. Barnard states that, “[i]n order to arouse a civic consciousness among people who hitherto knew or cared for nothing but their private concerns, Thomasius took up issues few dared to touch upon, and his language was bold and incisive” (584).

Although in English-speaking society, Christian Thomasius is a barely known advocator of ending the witch trials, within German society his name is often brought up as one of the founders of modern-day philosophy and politics. Part of his fame is due to his creation of the first successful public journals within a society which intellectuals often only spoke to other intellectuals. By doing this, Thomasius opened the door for something that was virtually unheard of, a conscious public. Barnard states that, “[i]n order to arouse a civic consciousness among people who hitherto knew or cared for nothing but their private concerns, Thomasius took up issues few dared to touch upon, and his language was bold and incisive” (584).

By informing the public, Thomasius took a stance that he fully believed; each human is an individual with individualistic reasonings why they would not obey any one’s but their own will. Further, he argued that each of these individuals should be told why they had to submit to a certain authority (law). Not only should the public have a say in their own behaviors, but each person’s morals are separate from their neighbors and should not be governed through politics. This belief system is echoed in his political works in which he touches on heresy and witch craft, and the need to allow their moral codes to catch up with them upon death and the afterlife, and, thus, allow law to deal with their physical crimes.

Throughout Christian Thomasius’ career as a jurist and academic, he was seen as the dawn of a new time for intellectual thinkers. However, very little is known or taught about him in the modern day, leaving academics of today to wonder if his beliefs were as truly influential as once thought. F.M. Barnard explores Thomasius’ work throughout his lifetime to consider whether this is truly a great thinker that was overlooked or simply an eclectic man who was given some form of power over the academic population and, thus, the political sphere.

One aspect of Thomasius’ work that greatly impacts how modern- day intellectuals see him is the content in which many of his beliefs are built upon. Thomasius had no qualms against repeating discoursed made by “Hobbes and Locke, Grotius and Pufendorf, and Descartes and Bayle […] Indeed, he was disarmingly open about his borrowings and almost excessively generous with praise for his ‘creditors’” (222). Utilizing these teaching of others, Thomasius created schools with the basis of “non-intellectual” rhetoric, in which the teacher taught, and the student followed. These lessons and beliefs were meant to be not stagnant, but rather continuously evolve and change when he deemed fit. This led to Christian Thomasius to question beliefs he once had and reopen questions that seemed already fully answered in the philosophical realm. This ability was one that was unheard of in the early modern period.

In a word, I consider that witch trials are useless, that the bodily horned devil with his pitch-ladle and his mother is a pure fabrication of popish priests, and that it is their greatest secret in order to frighten people with such devils so that they will pay money for masses for their souls, contribute rich inheritances and money to the endowments of monasteries or other pious causes and treat innocent people who cry “Father, what do you do?” as if they were sorcerers.

Christian Thomasius’ work is inherently framed as political due to content of governmental witchcraft trials and the unlikely-hood of the validity of the official statements that come from them. However, upon closer examination, there is a deep connection to what we would consider modern-day politics and the early modern period’s political issues within his work. One of the main points made by Thomasius’ in his discourse is on the subject of witchcraft (and heresy) being a moral error rather than a political one. He states that despite how a crime was committed, the criminal should be treated as any other criminal of the same crime. For instance: if a woman utilizes a pact with the devil to kill an infant, the woman should be punished for infanticide, but not the pact she made.

This opinion on morals vs law points towards the need of separation between church and state. Ian Hunter comments that, “Given this separation of law and morality, and the limitation of state action to the former, it is not surprising that Thomasius’ campaign against witch trials has been seen as a proto-liberal effort to set limits to government in the name of individual freedom and human reason” (257). Further, Thomasius’ views the witchcraft as a fallacy pushed by the church in order to ordain more power over the political sphere.

These instances seem to fuel his disdain towards the religious atmosphere and is easily found in his work, “ In a word, I consider that witch trials are useless, that the bodily horned devil with his pitch-ladle and his mother is a pure fabrication of popish priests, and that it is their greatest secret in order to frighten people with such devils so that they will pay money for masses for their souls, contribute rich inheritances and money to the endowments of monasteries or other pious causes and treat innocent people who cry “Father, what do you do?” as if they were sorcerers” (Thomasius).

De crimine magiae

Published in 1701, in this disputation Christian Thomasius rejects the idea of a “Devil’s alliances”. He calls for the end of witch trials, as he believes that it goes against the law. Thomasius also touched on atheism and claimed that executing atheist is unjust.

high wages

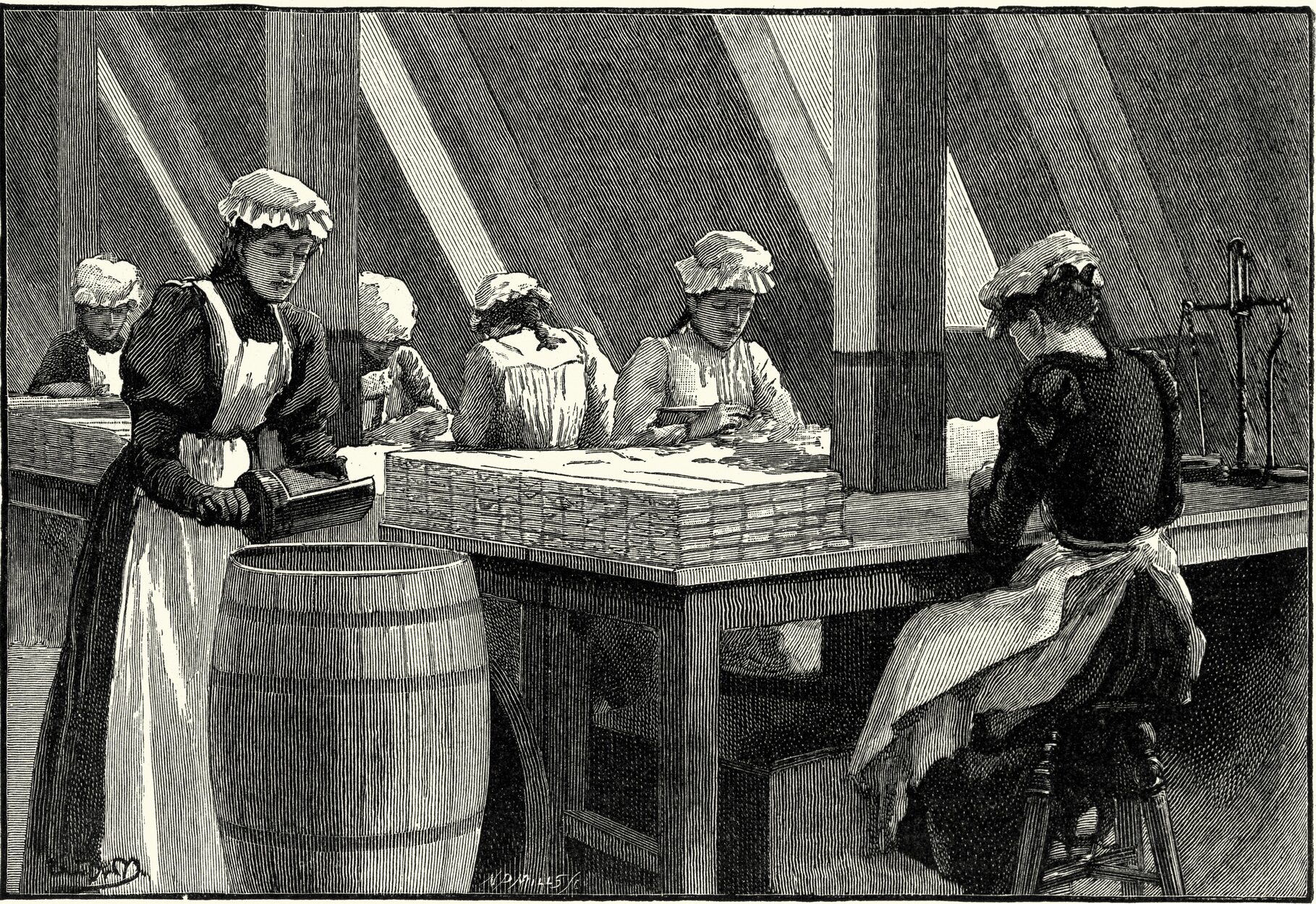

From "Lowell Mills and the 'Mill Girls,'" Massachusetts Historical Society, (2018):

"For this, mill owners and investors--led by men like Abbott Lawrence, John Amory Lowell, and Nathan Appleton--turned to New England's young women: accustomed to hard work and textile production in the home, educated, and serious-minded. Agents of the textile corporations ranged rural villages throughout New England, attracting young women to work in the mills with offers of high wages; once established, the mill girls themselves often recruited friends and relatives to come to Lowell and work alongside them."

From "Lowell Mills and the 'Mill Girls,'" Massachusetts Historical Society, (2018):

"In exchange, work in the mills provided good wages--from $1.85 to $3.00 per week--the highest in the country for women (although men working in the same mills were generally paid at least two times the salaries of women)."

From “Lowell Mill Girl Letters: Sarah George Bagley Letters” (1846):

“With the mean and paltry sum allowed to females, who work for the rich, you may be assured that I am obliged to make the most of my time and means as I possibly can.”

neat speec

From "Sarah Bagley Laboring for Life" by Teresa Murphy (2003):

"The public speaking that took place at the labor conventions was a particularly sensitive arena. Women who spoke in public at this time were commonly regarded as little better than prostitutes, and women who spoke in public to challenge economic or political arrangements were considered particularly vile examples of the species" (4).

Many of them educated the younger children of the family and young men were sent to college with the money furnished by the untiring industry of their women relatives.

From "Pleasures of Factory Life" in Lowell Offering by Sarah G. Bagley (1840):

"Another great source of pleasure is, that by becoming operatives, we are often to assist aged parents who have become too infirm to provide for themselves; or perhaps to educate some orphan brother or sister, and fit them for future usefulness."

From "Sarah Bagley Laboring for Life" by Teresa Murphy (2003):

"Sarah noted another benefit that would provide the theme for later articles: the ability to financially support one's parents, one's siblings, or oneself" (2).

seven vocations

From "Bennett Letters: M.M. Edwards" (1839):

"There are many young Ladies at work in the factories that have given up milinary dessmaking & shool keeping for to work in the mill."

From "Bennett Letters: Persis Edwards" (1840):

"I thought of learning the Milleners & Dressmakers trade but have failed in the attempt..."

From "Bennett Letters: Ann Blake" (1843):

"I think it would be best for me to work in the mill a year and then I should be better prepared to learn a traid."

From "Sarah Bagley Laboring for Life" by Teresa Murphy (2003):

"The rise of factories expanded women's economic roles and opportunities and increased their independence from their immediate families, but at the same time it rendered these new wage workers vulnerable to the vagaries of the economy, the health of their industry, and the control of their employers" (1).

aid of the family purse

From "Pleasures of Factory Life" in Lowell Offering by Sarah G. Bagley (1840):

"Another great source of pleasure is, that by becoming operatives, we are often to assist aged parents who have become too infirm to provide for themselves; or perhaps to educate some orphan brother or sister, and fit them for future usefulness."

From "Bennett Letters: Jemima W. Sandborn" (1843):

"You will probely want to know the cause of our moveing here which are many. I will menshion a few of them. One of them is the hard times to get aliving off the farm for so large famely so we have devided our famely...The rest of us have moved here to Nashvill thinking the girls and Charles they would probely work in the Mill."

From "Sarah Bagley Laboring for Life" by Teresa Murphy (2003):

"The Lowell, Massachusetts, mills relied overwhelmingly on the labor of young, unmarried, native-born white farm women - so called farmers' daughters and mill girls - whose families' financial situation propelled them into the new world of wage labor, at least until they married" (1).

five o’clock in the morning until seven in the evening, with one half-hour each, for breakfast and dinner.

From "An Account of a Visitor to Lowell" in The Harbinger (1836):

"The operatives work thirteen hours a day in the summer time, and from daylight to dark in the winter. At half past four in the morning the factory bell rings, and at five the girls must be in the mills. A clerk, placed as a watch, observes those who are a few minutes behind the time, and effectual means are taken to stimulate to punctuality. This is the morning commencement of the industrial discipline (should we not rather say industrial tyranny?) which is established in these associations of this moral and Christian community.

At seven the girls are allowed thirty minutes for breakfast, and at noon thirty minutes more for dinner, except during the first quarter of the year, when the time is extended to forty-five minutes. But within this time they must hurry to their boardinghouses and return to the factory, and that through the hot sun or the rain or the cold. A meal eaten under such circumstances must be quite unfavorable to digestion and health, as any medical man will inform us. At seven o'clock in the evening the factory bell sounds the close of the day's work.

Thus thirteen hours per day of close attention and monotonous labor are exacted from the young women in these manufactories. . . . So fatigued--we should say, exhausted and worn out, but we wish to speak of the system in the simplest language--are numbers of girls that they go to bed soon after their evening meal, and endeavor by a comparatively long sleep to resuscitate their weakened frames for the toil of the coming day."

Troops of young girls came

From "An Account of a Visitor to Lowell" in The Harbinger (1836):

"In Lowell live between seven and eight thousand young women, who are generally daughters of farmers of the different states of New England. Some of them are members of families that were rich in the generation before. . . ."

These boarding-houses were considered so attractive that strangers, by invitation, often came to look in upon them

From "An Account of a Visitor to Lowell" in The Harbinger (1836):

"We have lately visited the cities of Lowell and Manchester and have had an opportunity of examining the factory system more closely than before. We had distrusted the accounts which we had heard from persons engaged in the labor reform now beginning to agitate New England. We could scarcely credit the statements made in relation to the exhausting nature of the labor in the mills, and to the manner in which the young women - the operatives - lived in their boardinghouses, six sleeping in a room, poorly ventilated. We went through many of the mills, talked particularly to a large number of the operatives, and ate at their boardinghouses, on purpose to ascertain by personal inspection the facts of the case."

Sarah Bagley

Published "Pleasures of Factory Life" in December 1840.

Picture of Sarah George Bagley:

From "Sarah Bagley, the Voice of America's Early Women's Labor Movement" by Cara Giamo (2017):

"Twenty-eight-year-old Sarah Bagley made her way to Lowell in 1835, leaving her home in New Hampshire in the hope that she’d be able to send some extra money back to her struggling family. Like many of the mill girls, she embraced the cultural environment in Lowell, and in 1840, Bagley published a short essay in the Lowell Offering, a monthly literary magazine written and edited largely by mill girls. In the piece, called “Pleasures of Factory Life,” Bagley ruminated on the various good parts of her job—the new friends, the learning opportunities, the potted plants the women placed around the factory floor—but she gave special weight to the space the job left for thinking. As the body goes through the motions of twisting, pulling, and plucking, Bagley wrote, “all the powers of the mind are made active.” The looms themselves inspired further thought: “Who can closely examine all the movements of the complicated, curious machinery, and not be led to the reflection, that the mind is boundless,” she wrote, “and that it can accomplish almost any thing on which it fixes its attention!” (1-2).

From “Lowell Notes: Sarah Bagley.” Lowell National Historical Park, National Park Service:

"In 1844, the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association (LFLRA) was founded, becoming one of the earliest successful organizations of working women in the United States, with Sarah Bagley as its president” (2).

"The year 1845 also saw Sarah taking on new responsibilities as a writer and editor for the Voice of Industry, founded in 1844 by the New England Workingmen's Association."

From “Lowell Mill Girl Letters: Sarah George Bagley Letters” (1846):

"As I am President..."

Picture of “Constitution of the Lowell Factory Girls Association,” (1836):

http://americanantiquarian.org/millgirls/files/original/f91aeff28dda1b3eb89d82015a62c01b.jpg

wages were to be cut down

From “Lowell Notes: Sarah Bagley.” Lowell National Historical Park, National Park Service:

“By 1842 the pressure that Bagley had experienced as a weaver began to erupt in the form of labor conflict. In that year the Middlesex Manufacturing Company, one of Lowell’s textile giants, announced a speedup and subsequent 20% pay cut. In protest, seventy female workers walked out. All were fired and blacklisted” (1).

From "Sarah Bagley, the Voice of America's Early Women's Labor Movement" by Cara Giamo (2017):

"A few years later, exactly where Bagley had fixed her attention became clear. In the early 1840s, as factory owners tried to maximize profits in the face of a recession, the already-high demands of mill work ramped up. Many of these changes were sexist: In one mill, management cut wages for everyone; when the need for austerity ended, pay was raised again, but only for men. Another mill tried to double the number of looms that each weaver was responsible for. When a group of 70 women went on strike in response, they were not only fired, but blacklisted from ever getting another mill job. Earlier strikes by women workers—in 1834 and 1836—had ended similarly" (2).

first strikes

From “Lowell Mill Women Create the First Union of Working Women,” American Federation of Labor-Congress of Industrial Organizations, (2018):

“In the 1830s, half a century before the better-known mass movements for workers’ rights in the United States, the Lowell women organized, went on strike and mobilized in politics…and created the first union of working women in American history” (1).

“In 1834, when their bosses decided to cut their wages, the mill girls had enough…The mill girls ‘turned out’ – in other words, went on strike – to protest” (1).

“Management had enough power and resources to crush the strike” (1).

From "Sarah Bagley, the Voice of America's Early Women's Labor Movement" by Cara Giamo (2017):

"Driven by the foresight of the so-called 'Lowell Mill Girls,' American women have been going on strike at least since the 1830s, and thanks to the powerful rhetoric of one woman, Sarah Bagley, they began officially organizing not long after" (1).

legislative committee on the subject and plead, by their presence, for a reduction of the hours of labor

From “Lowell Notes: Sarah Bagley.” Lowell National Historical Park, National Park Service:

"In 1844, the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association (LFLRA) was founded, becoming one of the earliest successful organizations of working women in the United States, with Sarah Bagley as its president” (2).

"Working in cooperation with the New England Workingmen’s Association (NEWA) and spurred by a recent extension of work hours, the organizations submitted petitions totaling 2,139 names to the Massachusetts state legislature in 1845” (2).

“In response, the legislature called a hearing and asked Bagley, among eight others, to testify…the legislators ultimately refused to act against the powerful mills” (2).

"The year 1845 also saw Sarah taking on new responsibilities as a writer and editor for the Voice of Industry, founded in 1844 by the New England Workingmen's Association.

education

From "Pleasures of Factory Life" in Lowell Offering by Sarah G. Bagley (1840):

"In Lowell, we enjoy abundant means of information, especially in the way of public lectures. The time of lecturing is appointed to suit the convenience of the operatives; and sad indeed would be the picture of our Lyceums, Institutes, and scientific Lecture rooms, if all the operatives should absent themselves."

but their thoughts were free

From A New England Girlhood by Lucy Larcom (1889):

"I know that sometimes the confinement of the mill became very wearisome to me. In the sweet June weather I would lean far out of the window, and try not to hear the unceasing clash of sound inside. Looking away to the hills, my whole stifled being would cry out 'Oh, that I had wings!'" (54).

"Even the long hours, the early rising and the regularity enforced by the clangor of the bell were good discipline for one who was naturally inclined to dally and to dream, and who loved her own personal liberty with a willful rebellion against control" (57).

"I discovered, too, that I could so accustom myself to the noise that it became like a silence to me. And I defied the machinery to make me its slave. Its incessant discords could not drown the music of my thoughts if I would let them fly high enough" (57).

From "Pleasures of Factory Life" in Lowell Offering by Sarah G. Bagley (1840):

"But, aside from the talking, where can you find a more pleasant place for contemplation? There all the powers of the mind are made active by our animating exercise; and having but one kind of labor to perform, we need not give all our thoughts to that, but leave them measurably free for reflection on other matters. The subjects for pleasurable contemplation, while attending to our work, are numerous and various. many of them are immediately around us. For example: In the mill we see displays of the wonderful power of the mind. who can closely examine all the movements of the complicated, curious machinery, and not be led to the reflection, that the mind is boundless, and is destined to rise higher and still higher: and that it can accomplish almost any thing on which it fixes its attention!"

From "Bennett Letters: Persis Edwards" (1839):

"I work in the mill like very well enjoy myself much better than I expected am very confined could wish to have my liberty a little more but however I can put up with that as I am favored with other priveleges."

This was the greatest hardship

From “Lowell Mill Girl Letters: Sarah George Bagley Letters” (1846):

“Why by compelling females of New England to labor thirteen hours per day in rooms heated by hot air furnaces and sleep on the average from six to ten in a room. These very men are…mere partisans and not lovers of human rights."

ten-hour law

From “Lowell Mill Women Create the First Union of Working Women,” American Federation of Labor-Congress of Industrial Organizations, (2018):

“In 1847, New Hampshire became the first state to pass a 10-hour workday law – but it wasn’t enforceable” (2).

From “Lowell Notes: Sarah Bagley.” Lowell National Historical Park, National Park Service:

"The ten-hour workday was signed into law in 1874; only in 1920 did women gain a legal voice in national politics” (2).

Lucy Larcom

From “Lowell Mill Women Create the First Union of Working Women,” American Federation of Labor-Congress of Industrial Organizations, (2018):

"Lucy Larcom started as a doffer of bobbins when she was only 12 and 'hated the confinement, noise, and lint-filled air, and regretted the time lost to education,' according to one historian."

precedent

From “Lowell Mill Women Create the First Union of Working Women,” American Federation of Labor-Congress of Industrial Organizations, (2018):

“A second strike in 1836 – also sparked by wage cuts – was better organized and made a bigger dent in the mills’ operation. But in the end, the results were the same” (2).

From “A Quiet Strike.” Voice of Industry, by Cabolville Chronotype, 21 Nov. 1845:

“The ladies employed in the Spinning Room of Mill No. 2, Dwight Corporation, made a very quiet and successful “strike,” on Monday. The spinning machinery was set in motion in the morning, but there was no girls to tend it. They had heard a rumor that their wages were to be cut down, upon which they determined to quit" (1).

"They silently kept their resolve…when they were requested to return…[they received] an addition to their previous wage of fifty cents per week” (1).

“We think the girls have acted rightly, and by way of encouragement…we say ‘stick to your text,’ and pursue a steady course, with a determined spirit, and you will come off victorious” (1).

s Saul also among the prophets?

Found in Series II, Volume 4, 1843-1844 of the Lowell Offering

we are so tired

From "Lowell Mills and the 'Mill Girls,'" Massachusetts Historical Society, (2018):

"Over the years, working conditions in the mills deteriorated and wages decreased. Although the end of the war saw a temporary return of the mill girls to Lowell as factories rehired experienced hands to restart their factories, never again would young American women form the majority of the textile workforce."

foreign parentage

From "Lowell Mills and the 'Mill Girls,'" Massachusetts Historical Society, (2018):

"Beginning in about 1845, immigrants displaced by the Irish Potato Famine began flocking to Lowell in search of work. Willing to work for even lower wages (and to have their children work in the factories as well), they began to supplant Lowell's women workers. Successive waves of immigrants from other countries would take their place at the bottom of the mill hierarchy in turn."

Lowell Offering

From "Lowell Mills and the 'Mill Girls,'" Massachusetts Historical Society, (2018):

"Between 1840 and 1845, a literary magazine called the Lowell Offering published writings by the mill girls, edited and produced by their fellow workers."

social or literary advantages

From "Lowell Mills and the 'Mill Girls,'" Massachusetts Historical Society, (2018):

"Young women working in the Lowell mills availed themselves of circulating libraries, evening classes, lecture series, and literary and self-improvement clubs."

working hours

From "Regulations to be Observed by Persons Employed in the Boott Cotton Mills" (1866):

"All persons entering into the employ of the Company are considered as engaged to work twelve months, if the Company require their services so long."

From "Lowell Mills and the 'Mill Girls,'" Massachusetts Historical Society, (2018):

"Despite working an average of 73 hours per week."

good moral character,

From "Regulations to be Observed by Persons Employed in the Boott Cotton Mills" (1866):

"Any one who shall take from the mills, or the yard, any yarn, cloth or other article belonging to the Company, will be considered guilty of stealing, and prosecuted accordingly."

From "Lowell Mills and the 'Mill Girls,'" Massachusetts Historical Society, (2018):

"High standards of behavior were expected."

required her to attend regularly some place of public worship

From "Regulations to be Observed by Persons Employed in the Boott Cotton Mills" (1866):

"A regular attendance on public worship on the Sabbath, is necessary for the preservation of good order."

From "Pleasures of Factory Life" in Lowell Offering by Sarah G. Bagley (1840):

"In the mills, we are not so far from God and nature, as many person might suppose...And last, though not least, is the pleasure of being associated with the institutions of religion, and thereby availing ourselves of the Library, Bible Class, Sabbath School, and all other means of religious instruction."

From "Lowell Mills and the 'Mill Girls,'" Massachusetts Historical Society, (2018):

"The mill girls were subject to curfews and required to attend church, and signed contracts to that effect."

boarding-houses

From "Regulations to be Observed by Persons Employed in the Boott Cotton Mills" (1866):

"They are to board in one of the boarding-houses belonging to the Company, and conform to the regulations of the house where they board."

From "Lowell Mills and the 'Mill Girls,'" Massachusetts Historical Society, (2018):

"To this end, corporations established their own boardinghouses, supervised by women of good standing, where unmarried textile workers were required to live."

these needy people began to pour

From "Lowell Mills and the 'Mill Girls,'" Massachusetts Historical Society, (2018):

"In 1820, the town of East Chelmsford, Massachusetts, was a sleepy farming hamlet of 200 people. Just thirty years later, the renamed city of Lowell was home to thirty-two textile mills and a population that had grown to 33,000."

caste of the factory girl

From "Bennett Letters: M.M. Edwards" (1839):

"You have been informed I suppose that I am a factory girl...I suppose your mother would think it far beneith your dignity to be a factory girl."

From "Bennett Letters: Persis Edwards" (1840):

"I do not know what my employment will be this Summer. Mother is not willing I should go to the Factory."

From A New England Girlhood by Lucy Larcom (1889):

"His courtesy was genuine. Still, we did not call ourselves ladies. We did not forget that we were working-girls, wearing coarse aprons suitable to our work, and that there was some danger of our becoming drudges" (50).

The society of one another was of great advantage to these girls.

From A New England Girlhood by Lucy Larcom (1889):

"I found that the crowd was made up of single human lives, not one of them wholly uninteresting, when separately known. I learned also that there are many things which belong to the whole world of us together, that no one of us, nor any few of us, can claim or enjoy for ourselves alone" (57).

From "Pleasures of Factory Life" in Lowell Offering by Sarah G. Bagley (1840):

"Another source is found in the fact of our becoming acquainted with some person or persons that reside in almost every part of the country. And through these we become familiar with some incidents that interest and amuse us wherever we journey; and cause us to feel a greater interest in the scenery, inasmuch as there are gathered pleasant associations about every town, and almost every house and tree that may meet our view."

health

From "Regulations to be Observed by Persons Employed in the Boott Cotton Mills" (1866):

"They are not to be absent from their work without consent, except in case of sickness, and then they are to send the Overseer word of the cause of their absence."

From "Bennett Letters: M.M. Edwards" (1839):

"I would not advise any one to do it for I was so sick of it at first I wished a factory had never been thought of...My health is very poor indeed but it is better than it was when I left home."

From "Bennett Letters: Jemima W. Sandborn" (1843):

"Our famely is all in good health except myself. I have been qite out of health this spring but am much better now. The Doctor says I have the liver complaint."

From "Bennett Letters: Lucy Davis" (1846):

"After I had been there a number of days I was obliged to stay out sick but I did not mean to give it up so and tried it again but was obliged to give it up altogether. I have now been out about one week and am some better than when I left but not verry well. I think myself cured of my Mill fever as I cannot stand it to work there...My head is considerably affected since I went into the Mill...Next time I write I hope my head will feel better and I will write more..."

From "Pleasures of Factory Life" in Lowell Offering by Sarah G. Bagley (1840):

"We are placed in the care of overseers who feel under moral obligations to look after our interests; and, if we are sick to acquaint themselves with our situation and wants; and, if need be, to remove us to the Hospital, where we are sure to have the best attendance, provided by the benevolence of our Agents and Superintendents."

hours of labor were long

From A New England Girlhood by Lucy Larcom (1889):

"Even the long hours, the early rising and the regularity enforced by the clangor of the bell were good discipline for one who was naturally inclined to dally and to dream, and who loved her own personal liberty with a willful rebellion against control" (57).

five o’clock in the morning

From A New England Girlhood by Lucy Larcom (1889):

"No matter if we must get up at five the next morning and go back to our hum-drum toil" (50).

spinning-frames

From A New England Girlhood by Lucy Larcom (1889):

"My return to mill-work involved making acquaintance with a new kind of machinery. The spinning-room was the only one I had hitherto known anything about. Now my sister Emilie found a place for me in the dressing-room, beside herself. It was more airy, and fewer girls were in the room, for the dressing-frame itself was a large, clumsy affair, that occupied a great deal of space. Mine seemed to me as unmanageable as an overgrown spoilt child. It had to be watched in a dozen directions every minute, and even then it was always getting itself and me into trouble. I felt as if the half-live creature, with its great, groaning joints and whizzing fan, was aware of my incapacity to manage it, and had a fiendish spite against me. I contracted an unconquerable dislike to it; indeed, I had never liked, and never could learn to like, any kind of machinery. And this machine finally conquered me. It was humiliating, but I had to acknowledge that there were some things I could not do, and I retired from the field, vanquished" (71).

paid accordingly

From "Regulations to be Observed by Persons Employed in the Boott Cotton Mills" (1866):

"The time of the persons employed and the amount of labor performed by them, will be made up to the first Saturday of every month inclusive, and the sums due therefor, including board and wages, will be paid in the course of the following week."

overseers

From "Regulations to be Observed by Persons Employed in the Boott Cotton Mills" (1866):

"The Overseers are be punctually in their rooms at the starting of the mill, and not to be absent unnecessarily during work hours. They are to see that all those employed in their rooms are in their places in due season. They may grant leave of absence to those employed under them, when there are spare hands in the room to supply their places; otherwise they are not to grant leave of absence except in cases of absolute necessity."

regulation paper,

From "Regulations to be Observed by Persons Employed in the Boott Cotton Mills" (1866):

"These Regulations are considered a part of the contract with all persons entering into the employment of the Boott Cotton Mills."

regulation paper

Link for "Regulations to be Observed by Persons Employed in the Boott Cotton Mills" (1866):

Albert Parsons

unrelated misery

From "Pleasures of Factory Life" by Sarah Bagley in Lowell Offering, December 1840:

"And then you have so little leisure - I could not bear such a life of fatigue."

overruling hum of the iron animals

From A New England Girlhood by Lucy Larcom:

"I never cared much for machinery. The buzzing and hissing and whizzing of pulleys and rollers and spindles and flyers around me often grew tiresome" (47).

"I loved quietness. The noise of machinery was particularly distasteful to me...I discovered, too, that I could so accustom myself to the noise that it became like a silence to me. And I defied the machinery to make me its slave. Its incessant discords could not drown the music of my thoughts if I would let them fly high enough" (57).

From "Pleasures of Factory Life" by Sarah Bagley in Lowell Offering, December 1840:

"I could not endure such a constant clatter of machinery, that I could neither speak to be heard, nor think to be understood, even by myself."

three hundred and sixty-five days

From Early Factory Labor in New England by Harriet H. Robinson (1889):

"Those of the mill-girls who generally had homes generally worked from eight to ten months in the year; the rest of the time was spent with parents or friends" (6).

From "Regulations to be Observed by Persons Employed in the Boott Cotton Mills" (1866):

"All persons entering into the employ of the Company are considered as engaged to work twelve months, if the Company require their services so long."

married women;

From Early Factory Labor in New England by Harriet H. Robinson (1889):

"It may be said here that at one time the fame of the Lowell Offering caused the mill-girls to be considered very desirable for wives; and young men came from near and far to pick and choose for themselves, and generally with good success" (22).

The air swam with the fine, poisonous particles

From Early Factory Labor in New England by Harriet H. Robinson (1889):

"The health of the early mill-girls was good. The regularity and simplicity of their lives and the plain and substantial food provided for them kept them free from illness. From their Puritan ancestry they had inherited sound bodies and a fair share of endurance. Fevers and similar diseases were rare among them, and they had no time to pet small ailments" (15).

From "The Bennett Letters" (1839) by Melinda Blodgett:

"But I would not advise any one to do it for I was so sick of it at first I wished a factory had never been thought of. But the longer I stay the better I like and I think if nothing unforesene calls me away I shall stay here till fall...My health is very poor indeed but it is better than it was when I left home."

From "The Bennett Letters" (1846) by Lucy Davis:

"I could not get a chance to suit me, so I came here to work in the Mill. The work was much harder than I expected and quite new to me. After I had been there a number of days I was obliged to stay out sick but I did not mean to give it up so and tried it again but was obliged to give it up altogether. I have now been out about one week and am some better than when I left but not very well. I think myself cured of my Mill fever as I cannot stand it to work there...My head has been considerably affected since I went into the Mill...will you pleas to ask Miss Forbs to excuse me for not paying my bill...Pleas tell her if I do not come to H soon I shal send to you when I pay my assessments...Next time I write I hope my head will feel better and I will write more..."

It was subordinately surrounded by a cluster of other and smaller buildings, some of which, from their cheap, blank air, great length, gregarious windows, and comfortless expression, no doubt were boarding-houses of the operatives.

From Early Factory Labor in New England by Harriet H. Robinson (1889):

"Life in the boarding-houses was very agreeable. These houses belonged to the corporation, and were usually kept by widows (mothers of some of the mill-girls), who were often friends and advisers of their boarders. Each house was a village or community itself. There fifty or sixty young women from different parts of New England met and lived together...These boarding-houses were considered so attractive that strangers, by invitation, often came to look in upon them, and see for themselves how the mill-girls lived" (8-9).

"It was their [the mill-girls] custom the first of every month, after paying their board bill 9$1.25 a week0, to put their wages in the savings bank" (10).

girls

From A New England Girlhood by Lucy Larcom:

"Still, we did not call ourselves ladies. We did not forget that we were working-girls" (57).

From Early Factory Labor in New England by Harriet H. Robinson (1889): "Evening schools were soon established...Here might often be seen a little girl of ten puzzling over her sums in Colburn's Arithmetic, and at her side another 'girl' of fifty poring over her lesson in Pierpoint's National Reader" (8).

twelve hours to the day

From the "Sarah George Bagley" Letters:

"Why by compelling the females of New England to labor thirteen hours per day in rooms heated by hot air furnaces and sleep on the average from six to tn in a room" (1 Jan. 1846).

From "Sarah Bagley, the Voice of America's Early Women's Labor Movement" by Cara Giaimo (2017):

"Over Bagley's three-year term, the Association [Lowell Labor Female Reform Association, est. 1844] took on multiple projects. The most pressing of these was the 'Ten Hour Movement,' an attempt to get the grueling mill workday, which often lasted 12 to 14 hours, down to a slightly more manageable ten" (2).

From "Lowell Mill Women Create the First Union of Working Women" by the AFL-CIO (2018):

"A mill worker named Amelia - we don't know her full name - wrote that mill girls worked an average of nearly 13 hours a day" (1).

From Early Factory Labor in New England by Harriet H. Robinson (1889):

"The working hours of all girls extended from five o'clock in the morning until seven in the evening, with one-half hour each, for breakfast and dinner. Even the doffers ["very young girls" who "doffed, or took off, the full bobbins from the spinning-frames, and replaced them with empty ones" (6). Robinson worked as a doffer as a child in the mills.] were forced to be on duty nearly fourteen hours a day. This was the greatest hardship in the lives of these children" (6).

served mutely and cringingly as the slave serves the Sultan

A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers by Henry David Thoreau

In a section of Thoreau’s novel, A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, he describes the fate of the shad fish as caused by the Billerica dam. Thoreau describes how the dam and factories along the river are destroying the river and the fish. He describes the shad thus, “Armed with no sword, no electric shock, but mere Shad, armed only with innocence and a just cause, with tender dumb mouth only forward, and scales easy to be detached.” This description of the “poor shad” is reminiscent of the description of the girls in the factory. The narrator describes the girls as “blank-looking girls” which parallels “innocence.” The narrator also describes the machine that makes the paper, “Nothing was heard but the low, steady, overruling hum of the iron animals. The human voice was banished from the spot. Machinery--that vaunted slave of humanity--here stood menially served by human beings, who served mutely and cringingly as the slave serves the Sultan.” This quote can be compared to how Thoreau describes the shad, “with tender dumb mouth only forward, and scales easy to be detached.” The shad are slaves of the Billerica dam, to serves human needs, just as the girls are slaves to the machinery in the mill to serve the bachelors. Thoreau also asks, “Who hears the fishes when they cry?” Who hears the girls working in the factory? No one. For none of the dialogue in the story belongs to a female character. Those who are oppressed do not have a voice to stand up for themselves.

M.J. Tortessi

haggard

Pioneer Paper-making In Berkshire: Life, Life Work And Influence of Zenas Crane by Joseph Edward Adams Smith

This source is a book about the life of Zenas Crane and his work with his paper mill (the same paper mill that Melville visited in 1851). This book helps to inform Melville’s story because it describes the scenery of where the paper mill was located. The book states that Crane “reached a region of superb natural beauty, and moreover discovered a location exactly suited to his purpose as a paper-maker. In the town of Dalton...lies a sheltered valley through which flows the largest of the eastern branches of the Housatonic river, affording in its rapid descent several fine water powers” (16). In the story, the paper mill is also in a valley, though the scenery is not described as “superb natural beauty,” but as “bleak,” “violent,” and “haggard,” and the river, aptly named “Blood River,” is described as “brick-colored,” and “strange-colored,” implying that the river in 1851 is much more polluted from the factory than it was in 1799 when Crane first chose the spot for his mill.

M.J. Tortessi

are indiscriminately called girls, never women?"

This wanted advertisement is from the Berkshire County Whig in 1842. It states, “Wanted. 10 OR 12 GIRLS to work in the Paper Mill of the subscribers at Dalton. Z. CRANE & SONS.” This advertisement informs Melville’s story because the advertisement is looking for workers and uses the word “GIRLS” in all capital letters. The narrator asks the proprietor, “Why is it, Sir, that in most factories, female operatives, of whatever age, are indiscriminately called girls, never women?” This is an ad for workers for the very same mill that Melville will visit in just nine years. And clearly the workers are all “girls.”

M.J. Tortessi

he business is poor in these parts

From Early Factory Labor in New England (1889) by Harriet H. Robinson:

"Troops of young girls came from different parts of New England...some of these were daughters of sea captions (like Lucy Larcom), of professional men or teachers, whose mothers, left widows, were struggling to maintain the younger children. a few were the daughters of reduced circumstances, who had left home 'on a visit' to sent their wages surreptitiously in the aid of the family purse" (4).

"Some of the mill-girls helped maintain widowed mothers, or drunken, incompetent, or invalid fathers. Many of them educated the younger children of the family and young men were sent to college with the money furnished by the untiring industry of their women relatives. The most prevailing incentive to labor was to secure the means of education for some male member of the family. To make a gentleman of the brother or a son, to give him a college education, was the dominant thought in the minds of a great many of the better class of mill-girls. I have known more than one to give every cent of her wages, month after month, to her brother, that he might get the education necessary to enter some profession" (11).

"Its is well to digress here a little, and speak of the influence the possession of money had on the characters of some of these women. We can hardly realize what a change the cotton factory made in the status of the working women. Hitherto woman had always been a money saving rather than a money earning, member of the community. Her labor could command but small return. If she worked out as servant, or 'help,' her wages were from 50 cents to $1.00 a week; or, if she went from house to house by the day to spin and weave, or do tailoress work, she could get but 75 cents a week and her meals. As teacher her services were not in demand, and the arts, the professions, and even the trades and industries, were nearly all closed to her" (11-12).

"As late as 1840 there were only seven vocations outside the home into which the women of New England had entered. At this time woman had no property rights. A widow could be left without her share of her husband's (or the family) property, an "incumbrance" to his estate. A share of the inheritance. He usually left her a home on the farm as long as she remained single. A woman was not supposed to be capable of spending her own, or of using other people's money" (12).

From "The Bennett Letters" (1839) by Melinda Blodgett:

"There are many young Ladies at work in the factories that have given up milinary dessmaking & shool keeping for to work in the mill."

From "The Bennett Letters" (1843) by Jemima Sandborn:

"You will probely want to know the cause of our moveing here which are many. I will menshion a few of them. One of them is the hard times to get aliving off the farm for so large famely so we have devided our family...The rest of us have moved here to Nashvill thinking the girls and Charles they would probely work in the Mill but we have had bad luck giting them in."

These rapid waters unite at last in one turbid brick-colored stream, boiling through a flume among enormous boulders. They call this strange-colored torrent Blood River.

Singh, P., Katiyar, D., Gupta, M. and Singh, A. (2011) ‘Removal of pollutants from pulp and paper mill effluent by anaerobic and aerobic treatment in pilot-scale bioreactor’, Int. J. Environment and Waste Management, Vol. 7, Nos. 3/4, pp.436–444.

This scientific essay discusses the effluent (chemical waste) that is produced during the paper-making process. The essay states that a pulp and paper mill produces effluent that is “highly polluted and is characterised by parameters unique to these waste such as colour.” The essay continues to describe the color that water turns due to the pollutants being released: “The discharge of untreated effluents from pulp and paper mills into water bodies damage the water quality (Singh et al., 2002). The brown colour imparted to water due to the addition of effluents is detectable over long distances (Crawford et al., 1987).” The significance of this research is when the essay describes the color of the water as “brown.” This informs Melville’s story because the narrator describes the river that powers the paper mill as a “brick-colored stream” and “strange-colored.” This parallels the description of polluted water from the essay. The river that powered the mill that Melville actually visited in 1851 is the Housatonic River, but when writing the story, Melville changes the name of the river to “Blood River,” which again emphasizes the brown color of the water that occurs from the pulp and paper effluent that is released into the river during the paper-making process.

M.J. Tortessi

"'Tis not unlikely, then," murmured I, "that among these heaps of rags there may be some old shirts, gathered from the dormitories of the Paradise of Bachelors.

money.cnn.com/2010/08/09/smallbusiness/cranes/index.htm

This article, published by CNN Money, provides a history of the paper mill Crane & Co.--the same mill that Melville visited in 1851. The company has been in business for over 200 years and prides itself on the claim that the company, “supplied Paul Revere with the paper that served as the American colonies’ first non-coin money.” During the mill’s early days, the company made “drafting paper,” “stock certificate,” and “highly combustible rifle paper.” This informs the text because when Cupid is taking the narrator around the facility, the narrator notes that the paper the girls make will become “sermons, lawyer’s briefs...love-letters, marriage certificates...and so on,” just like the article states. However, the girls in the story will never be able use paper for such things as “love-letters,” much like the current workers at Crane & Co. who make American currency, will never see the amount of money in their personal lives that they see being created in the mill. The article also states that the mill created “men’s paper shirt collars--which were the wave of fashion in the 1800s.” In the story, when Cupid and the narrator are coughing in the “rag-room,” the narrator whispers, “Tis not unlikely, then...that among these heaps of rags there may be some old shirts, gathered from the dormitories of the Paradise of Bachelors.” This phrase is really interesting in relation to the article because the “girls” working in the mill were making the paper collars for the bachelors across the ocean. For surely, the Bachelors were up with the “wave of fashion.”

M.J. Tortessi

an eye supernatural with unrelated misery

www.cranecurrency.com/company/history/

This article, which can be found on the Crane & Co. website, describes the history of the company through a very patriotic lens. The history, according to their website, says that the company began in 1775. The company associates itself with Paul Revere and American independence. This is interesting, because according to the novel, Pioneer Paper-making In Berkshire: Life, Life Work And Influence of Zenas Crane, Crane & Co. wasn’t founded until 1799, well after 1775 and the war for independence. However, the company is adamant about associating itself with independence and the “American Dream.” Therefore, it is shocking when compared to the state of the mill and its workers as described in Melville’s text. The girls have no independence and the girls will never be able to achieve the “American Dream.”

M.J. Tortessi

condemned state-prisoners

www.britannica.com/technology/papermaking

This article describes the paper-making process from the early days through the 19th century. This article is very informative because it describes the different chemicals used throughout the process. According to the article, these chemicals started being used in the 19th century. When further research is performed about the negative effects of these chemicals it starts to make a lot of sense about why Melville described the girls in the factory as “pallid,” “blank,” and “condemned state-prisoners.” Below is a list of some of the chemicals used in the paper-making process and their ill effects:

Praxair. Sulfur dioxide. 2016, p. 1, Safety Data Sheet P-4655.

Sulfur dioxide

Occidental Chemical Corporation. Caustic Soda Liquid (All Grades). 2015, p. 1-2, Safety Data Sheet M32415.

Caustic soda

Science Lab: Chemicals & Laboratory Equipment. Sulfurous Acid. 2013, p. 1, Safety Data Sheet SLS3352.

Sulfurous acid

Science Lab: Chemicals & Laboratory Equipment. Calcium Hypochlorite. 2013, p. 1, Safety Data Sheet SLC3310.

Calcium hypochlorite (bleach)

Science Lab: Chemicals & Laboratory Equipment. Sodium Hypochlorite. 2013, p. 1, Safety Data Sheet SLS1654.

Sodium hypochlorite (bleach)

Airgas: An Air Liquide Company. Chlorine. 2017, p. 1, Safety Data Sheet 001015.

Gaseous chlorine (an ingredient for Mustard Gas)

M.J. Tortessi

But foolscap being in chief demand, we turn out foolscap most

Foolscap is a highly used size of paper with specific dimensions and varying quality, and was popular with letter writers. This type of paper was smaller, so it was more manageable for writing and folding for envelops. Despite what people often think, foolscap wasn't a reference to the quality of paper, but instead was named after the watermark traditionally used for this paper.

Annotation: Vicci

Lawyer

Herman Melville was said to have been inspired by the Inns of Court in crafting Part I of The Paradise of Bachelors and the Tartarus of Maids. The Inns of Court were four societies in London whole members were lawyers and were called to the bar as barristers.

Briana

Westminster

Provisions of Westminster and Statues of Westminster were landmark legal acts. The Provisions of Westminster were legislative improvements that were made after Henry III of England and his barons became at odds with one another. The Statutes of Westminster described how much power English Commonwealths were to have.

Briana

Temple Church

The Temple Church owes its name to the Middle and Inner Temple, which are two of the four Inns of Court.

Briana

elderly person

From Early Factory Labor in New England (1889) by Harriet H. Robinson:

"The early mill-girls were of different ages. Some (like the writer) were not over ten years of age: a few were in middle life, but the majority were between the ages of sixteen and twenty-five" (6).

stunted wood

In a brief diary entry by Susan Fenimore Cooper in November of 1849, she describes crossing the Oakdale River. She states, “Its broad shallow stream turns several mills, one of them a paper-mill, where rags from over the ocean are turned into sheets for Yankee newspapers.” This section is interesting in that it implies that Europe is sending old rags to this paper-mill to create newspapers. This coincides with Melville’s story when the narrator whispers, “Tis not unlikely, then...that among these heaps of rags there may be some old shirts, gathered from the dormitories of the Paradise of Bachelors.” The Paradise of Bachelors is located in London--over the ocean. Cooper also describes the area around the mill. She states, “One of the few sycamores in the neighborhood stands by the bridge.” The important part of this quote is “one of the few,” implying that there are not many sycamore trees remaining because the paper-mill has cleaned the area of most trees for use in the mill. This description of the landscape correlates to Melville’s description of the land around the mill that the narrator visits. He describes it as “bleak hills,” “haggard rock,” and “stunted wood.” The only evidence of trees are in the description “the sullen background of mountain-side firs, and other hardy evergreens, inaccessibly rising in grim terraces for some two thousand feet.” Implying that these trees are the only ones that remain merely because they are inaccessible. Again, the paper-mill has destroyed and cleaned out the landscape.

M.J. Tortessi

John Locke

Let us then suppose the mind to be, as we say, white paper void of all characters, without any ideas. How comes it to be furnished? Whence comes it by that vast store which the busy and boundless fancy of man has painted on it with an almost endless variety? Whence has it all the materials of reason and knowledge? To this I answer, in one word, from EXPERIENCE.

Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690)

Templar's

The Knights of Templar were a Catholic military order composed of men who pledged to protect pilgrims on their journey to the Holy Land. They were known for their bravery and quickly gained power and wealth.

Briana

whited sepulchre

Matthew 23:27 Woe unto you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! for ye are like unto whited sepulchres, which indeed appear beautiful outward, but are within full of dead men's bones, and of all uncleanness.

blank-looking girls