their abrupt click breaking through the mortiferous layer of the Pose.

"Mortiferous" means deadly. For Barthes, the mechanical, very real sound of the camera shutter clicking breaks through the fakeness and death-anticipation of being photographed.

their abrupt click breaking through the mortiferous layer of the Pose.

"Mortiferous" means deadly. For Barthes, the mechanical, very real sound of the camera shutter clicking breaks through the fakeness and death-anticipation of being photographed.

his eye (which terrifies me)

The "eye" of the photographer, or the lens of the camera, "terrifies" Barthes because they are the things over which he has no control; they will determine the look of his portrait photograph and influence the way others interpret it.

The shutter of the camera, and the click sound that it makes, however, are solid, material, predictable, and therefore comforting things.

eidos

The "ethos" of a culture is a set of core beliefs and ideals that guide its members' feelings toward life; while the "eidos" is the intellectual approach taken toward examining it.

When Barthes says that "Death is the eidos of the camera," he is saying that the purpose of a portrait photograph is the "death" of its subject, in the sense that it captures the image of a thing that will eventually die, and preserves it by rendering it still and lifeless.

It is my political right to be a subject which I must protect.

A subject has a voice and a degree of control; an object does not. Barthes believes it is a poltitical act to try to prevent oneself from becoming an object, or being objectified, by a photograph.

Think about how this applies to the facial recognition technology in wide use today.

disinternalized

When something is "internalized," it is so very much a part of you that you are almost unaware of it. To "disinternalize" something is to take that interior, private state and make it exterior and public, so that it loses its deep connection to you, and to its private meaning.

recent bereavement

He was mourning the death of his mother.

hey turn me, ferociously, into an object, they put me at their mercy, at their disposal, classified in a file

He is talking about what happens to photographs; how they are used and interpreted, or discarded and forgotten, independently of the will of the people in them.

when I discover myself in the product of this operation, what, I see is that I have become Total Image, which is to say, Death in person

When he looks at a photograph of himself, he sees a ghost of himself because he doesn't recognize his own spirit within it. He also imagines others looking at it after his death.

what society makes of my photograph, what it reads there, I do not know

Barthes is saying that he has no control over what others will think of the photograph of him, what they will think of him, or what conclusions they will draw about him based upon it. He also recognizes that he has no control over its duplication or use.

terrified

Barthes believes the portrait photographer's greatest fear is failing to make the subject look truly alive. For him, this is irony, because he sees the photograph as a form of death.

lifelike

Barthes goes on to note the list of fake scenes to be captured in photos that will be perceived as reality.

plastron

This is a reference to the writing of Marquis de Sade (1740-1814), after whom the term "sadism" was named, who was famous for his sexual exploits.

Sade wrote about French houses of prostitution, in front of which prostitutes were sometimes stationed to handle the advancing men. He likened these women to "plastrons," which is the French word for an armored breastplate that protects the torso against projectiles.

Barthes thinks of himself posing for the lens as creating a "plastron" for the camera: A solid piece of armor, passively placed, to protect what is within. He likens the act of being photographed to an act of prostitution, in the way that both elicit a sort of passive guardedness against a consensual violation.

I then experience a micro-version of death (of parenthesis): I am truly becoming a specter.

"Barthes loves paradox, and becoming four things at once (five if you count dead) makes his compulsive posing of the greatest interest to him. Portrait photography itself (the entire subject of Barthes’s book) is always a paradox. He looks at a very old picture of two young girls and has the vertiginous realization that 'They have their whole lives before them; but also they are dead (today), they are then already dead (yesterday).' Therefore, 'each photograph always contains this imperious sign of my future death.'" https://slowreads.com/2011/07/13/death-and-photography/

a subject who feels he is becoming an object

The moment of shooting a photo is a meaningful split second of time, during which a person is transformed into an object.

imposture

Pretending to be someone else in order to deceive others.

inauthenticity

Posing for a photograph feels like being fake.

I am at the same time: the one I think I am, the one I want others to think I am, the one the photographer thinks I am, and the one he makes use of to exhibit his art.

Think about the fact that a photograph is an image of you over which you have no control, and whose interpretation may be very far from your image of yourself.

image-repertoires

"A set of images fuctioning as a misunderstanding of the subject." https://books.google.com/books?id=CJO-kUld-24C&pg=PA67&lpg=PA67&dq=image-repertoire+meaning&source=bl&ots=yDRLSFvoSh&sig=ACfU3U3pqKzvj7mpEJRIzWrLj4YDpcivdw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwingOndtITrAhWhna0KHW-5DU4Q6AEwBXoECAkQAQ#v=onepage&q=image-repertoire%20meaning&f=false

this headrest was the pedestal of the statue I would become, the corset of my imaginary essence.

Barthes uses language poetically; his statements are layered with symbolic meaning.

He explains that portrait photographers of the 1800s used a device to help people hold still for the long exposure of the photograph. It involved a headrest, which being behind the head, was invisible to the camera.

Metaphorically, Barthes stands upon this antique headrest now as if it were a pedestal, and he makes himself into a statue on it as he poses for a photograph.

This turning of himself into a statue confines and immobilizes him, in a sense, like a corset would.

assume long poses

While photos today are usually taken in a spit second, the first photographs required extremely long exposure times. The earliest photos - daguerreotypes - took 15 minutes to expose, so they were totally impractical for photographing people.

Early forms of portrait photography required people to sit perfectly still without blinking in bright sunlight for about 15 seconds, which is longer than it sounds. https://dp.la/exhibitions/evolution-personal-camera/early-photography

Photography transformed subject into object

If you allow someone to take your photo, then you are the subject of the photo. The photo itself, however, is an object.

Is landscape itself only a kind of loan made by the owner of the terrain?

This statement can be interpreted both literally and metaphorically.

Literally, if you want to take a photograph of a landscape on property that is owned by someone else, you have to get their permission to be there, and to take and use the photo. The owner is "lending" you their lanscape.

Metaphorically, "landscape" can mean any subject of any photograph. The subject of the photo is generally another person, or something owned by another person.

ownership

Who owns your body? Who owns the image of it? Doesn't a photograph of you impart a kind of ownership over you, or your image, to the individual who possesses it?

that faint uneasiness which seizes me when I look at "myself" on a piece of paper.

He is talking about the discomfort one feels in seeing oneself anywhere aside from a mirror. He refers to the phenomenon of "doubles," or thinking you've seen yourself from a distance, which was a theme in European literature.

profound madness of Photography

Barthes says there is "profound madness" in photography because it allows you to see a double of yourself. Before the invention of photographic technology, it would have been "madness" - crazy - to think that you saw yourself anywhere but in a mirror, or possibly reflected off a body of water.

hallucinosis

"A mental disorder the symptom of which is hallucinations, commonly associated with the ingestion of alcohol or other drugs." https://www.dictionary.com/browse/hallucinosis#:~:text=%2F%20(h%C9%99%CB%8Clu%CB%90s%C9%AA%CB%88n%C9%99%CA%8As%C9%AAs)%20%2F-,noun,of%20alcohol%20or%20other%20drugs

Heautoscopy

"Heautoscopy is a term used in psychiatry and neurology for the reduplicative hallucination of seeing one's own body at a distance. It can occur as a symptom in schizophrenia and epilepsy." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autoscopy#:~:text=Heautoscopy%20is%20a%20term%20used,possible%20explanation%20for%20doppelg%C3%A4nger%20phenomena.

the Photograph is the advent of myself as Other: a cunning dissociation of consciousness from identity

A photograph captures a version of you that feels alien to you as soon as you see it. Further, It goes out into the world to represent you, without your awareness.

I want a History of Looking.

Barthes wants us to consider the history of the image, and how changing technology has "disrupted," or at least transformed, society.

To see oneself (differently from in a mirror): on the scale of History, this action is recent, the painted, drawn, or miniaturized portrait having been, until the spread of Photography, a limited possession

Prior to the invention of photography, the only way a person could ever see an image of themselves, aside from in a mirror, was by having a portrait painted. It was expensive, but an artist could make you look more attractive than perhaps you were in person.

turns you into a criminal type

To Barthes, a snapshot looks a lot like a "mugshot" - the official photograph of a person under arrest.

Photomat

In the days of film, as opposed to digital, photography, a photomat was a store you took your film to, to have printed photos made.

perhaps only my mother?

For context: This book is, in part, a meditation on his mother's death.

Alas, I am doomed by (well-meaning) Photography always to have an expression

A photograph captures a split second, and a momentary facial expression is fixed for all time, regardless of what it meant, or whether it meant anything at all.

the image which is heavy, motionless, stubborn

A photograph is a moment in time, fixed in place forever, while a person is continually in motion and changing.

"myself' never coincides with my image

The photo feels unrelated to how he sees himself.

image, buffeted among a thousand shifting photographs, altering with situation and age, should always coincide with my (profound) "self"

Again, Barthes wants a photo to represent his image of himself.

effigy

A material representation of a person, like a sculpture or a painting.

to square the circle

To bring the argument back around to its beginning premise.

I lend myself to the social game, I pose

Ironically, he is consciously composing a fake image in order to make the result represent him more truly.

I don't know how to work upon my skin from within

Barthes doesn't know how to make his body create an image for the camera that he feels really represents who he is.

Photography is anything but subtle

A bad photo can make you look really bad, and it takes a skilled photographer to shoot a really good portrait photo.

what I want to have captured is a delicate moral texture and not a mimicry

He wants the photograph to capture his essence, or his spirit, the way a painting might, rather than an exactly faithful copy of however superficially good or bad he might look that day.

painted

Barthes wishes that a photo was as easy to control as a painting is, in terms of how good it makes the person look. Bear in mind that he lived before the time of Instagram, Photoshop, and digital photo filters. Someone took a photo of you on film, which neither one of you could see until the film was developed and printed, and that took time and money.

antipathetic

Unlikeable.

filiation

Google definition:"the manner in which a thing is related to another from which it is derived or descended in some respect." A family relationship.

In other words, Barthes is uncertain of his relationshp to a photograph of himself. Is his body the creator and master of the image, or does he unconsciously pose his body for the creation of an image, or does the image create his body for whoever looks at it?

I derive my existence from the photographer

Barthes passed away in 1980, but looking at a photo of him on Google, always with a cigarette or cigar dangling in his mouth, brings him to life for us, in a way.

I do not risk so much as that

Barthes is admitting that photos don't endanger him, the way they did the Communards.

Communards paid with their lives for their willingness or even their eagerness to pose on the barricades: defeated, they were recognized by Thiers's police and shot, almost every one)

In 1871, the French were defeated and occupied by the German kingdom of Prussia. The people of Paris fought back by establishing a socialist commune in the middle of Paris; the rebels posed proudly for photos on the barricades they built. Their resistance was brutally put down by the Prussians, who killed tens of thousands of people. Barthes refers here to the fact that photos were used to identify and track down the rebels. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Communards

mortiferous

Google definition: deadly.

caprice

Google definition: "a sudden and unaccountable change of mood or behavior."

the Photograph creates my body or mortifies it

A photograph "creates" your body because firstly, you pose for it, and secondly, it represents that body when people look at it later on.

Barthes goes on to explain in the next sentence that a photograph can be deadly, too.

transform myself in advance into an image.

When someone points a camera at you, you turn yourself into a superficial version of yourself for the lens to capture, don't you?

once I feel myself observed by the lens, everything changes: I constitute myself in the process of "posing,"

Think about how you react to a camera pointed at you. Don't you immediately think about how you look? Do you immediately pose? Or run away?

too often, to my taste

Despite the popularity of selfies and Instagram, many people still dislike being photographed.

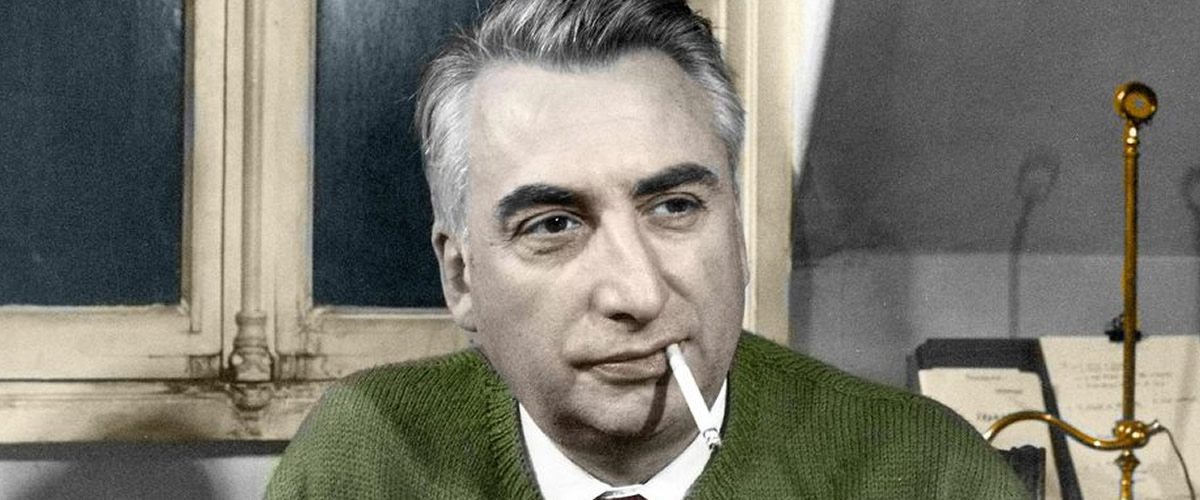

Roland Barthes

1915 - 1980, a French philosopher whose thinking had an influence on late 20th century anthropology.

I have determined to be guided by the consciousness of my feelings

Barthes set out to write a book that was based exclusively on his own personal experiences, rather than what he had read or heard about.

Reflections on Photography

The title is a play on words, because a photograph is a reflection of an object.