OMGoodness! I see why no one went to his lectures. What is he saying is that the scientific community has done some experiments and these experiments give us results that make us think the relationship between density and the "quantity" of a material (the amount of matter, now know as the mass) is directly proportional. Here's how the math works out:

He starts with...

- I have a gas of some density, \(d_{1}\). Using \(d_{1}\) is a fancy =, mathy way to say-- I'm going to talk about a lot of things called d. Just remember, this one is the first one. We don't know what \(d_{1}\) is equal to. But, we don't need to yet. We just need to remember that

$$density{1} = \frac{mass{1}}{volume_{1}}$$

- Now, if you have a new gas whose density (we will be calling that \(d_{2}\) )is equal to \(2*d_{1}\) . But, \(volume_{2} = 2*volume_{1}\).

- How much "quantity" (matter) is there in the new gas? Basically, what is \(mass_{2}\) equal to? Let's find out:

Here are the facts we are given:

$$d{1}= \frac{mass{1}}{volume{1}}$$ AND $$d{2} = 2*d_{1}$$

I will substitute what \(d_{1}\) equals in the first equation into the second equation and I get this:

$$d_{2} = 2*\frac{mass_{1}}{volume_{1}} $$

But, we can also say \(d_{2}\) this way:

$$\frac{mass_{2}}{volume_{2}}

$$

So, I substitute that in on the left hand side and we get this:

$$\frac{mass_{2}}{volume_{2}} = 2*\frac{mass_{1}}{volume_{1}}$$

But, he says we have "double space" in the second case. So, I can substitute \(2*volume_{1}\) for \(volume_{2}\). That gives us:

$$\frac{mass_{2}}{2*volume_{1}} = 2*\frac{mass_{1}}{volume_{1}}$$

If I multiply both sides by \(volume_{1}\), I am left with:

$$\frac{mass_{2}}{2} = 2*mass_{1}$$

Multiply both sides by 2 and we get:

$$mass_{2}= 4*mass_{1}$$

Yep, the "quantity" has quadrupled. You can try the next one about the triple in space (volume) for yourself.

Image from

Image from  Source:

Source:

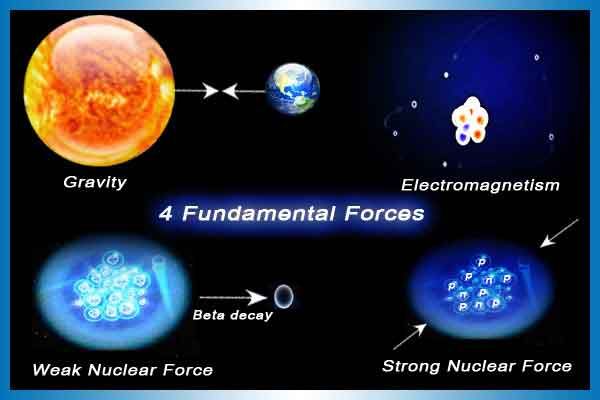

Image is from a great article on proportionality at

Image is from a great article on proportionality at  Image Credit:

Image Credit:

Even their dining hall looks like the one at Hogwarts:

Even their dining hall looks like the one at Hogwarts:

And, students have to wear robes to classes. So, I guess if you don't end up getting your letter from Hogwarts, you can always go here for college or grad school as a consolation. (This is from Oxford-- another Hogwarts alternative that also requires academic/wizard robes.)

And, students have to wear robes to classes. So, I guess if you don't end up getting your letter from Hogwarts, you can always go here for college or grad school as a consolation. (This is from Oxford-- another Hogwarts alternative that also requires academic/wizard robes.)

But, what Planck found out was that the energy comes in distinct buckets. So, it would look more like this in reality:

But, what Planck found out was that the energy comes in distinct buckets. So, it would look more like this in reality: