who talked continuously seventy hours from park to pad to bar to Bellevue to museum to the Brooklyn Bridge, a lost batallion of platonic conversationalists jumping down the stoops off fire escapes off windowsills off Empire State out of the moon yacketayakking screaming vomiting whispering facts and memories and anecdotes and eyeball kicks and shocks of hospitals and jails and wars,

Kerouac: Essentials of Spontaneous Prose

Part of what makes Howl, and other Ginsberg/beat writings of the era, so captivating is the style of writing that the beats were known to employ in their works. Ginsberg's literary blitzkrieg mirrors the chaos of the world he lives in, which he is forced to survive in amidst the disarray and confusion of living within a society that punishes the non-conformers.

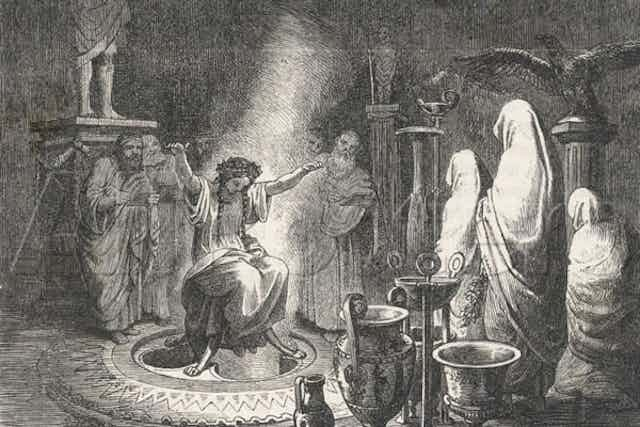

There are numerous references to Greek mythology in this passage, hence my accompanying image of the oracle of Delphi.

There are numerous references to Greek mythology in this passage, hence my accompanying image of the oracle of Delphi.  The hyacinth has two symbolic meanings, depending on how you choose to interpret the context: The first is either a sense of jealously, which stems from the Greek myth of the origin of the flower's name, and the second is newfound love. Given the context of modernism as background information for when this piece was written & published, I am inclined to believe that the appearance of the hyacinth in this poem is meant to evoke the latter.

The hyacinth has two symbolic meanings, depending on how you choose to interpret the context: The first is either a sense of jealously, which stems from the Greek myth of the origin of the flower's name, and the second is newfound love. Given the context of modernism as background information for when this piece was written & published, I am inclined to believe that the appearance of the hyacinth in this poem is meant to evoke the latter. These lines evoke the imagery of Sascha Schneider's famous painting, Hypnosis, to me. The hyacinth girl is a contrast to the narrator's conflict between the living world and the dead, which perhaps ties back into the theme of doubleness we explored recently.

These lines evoke the imagery of Sascha Schneider's famous painting, Hypnosis, to me. The hyacinth girl is a contrast to the narrator's conflict between the living world and the dead, which perhaps ties back into the theme of doubleness we explored recently.