Confederation

The idea of confederation was brought up in 1839 by Lord Durham, in his Report on the Affairs of British North America. In 1837 some areas of Canada began to experience rebellions. In response to the turmoil, Durham was sent by Great Britain to investigate the cause of these rebellions, thus the foundation of his report. In his report he said that “It is not necessary that I should take any pains to prove that this is a state of things which should not, which cannot continue. Neither the political nor the social existence of any community can bear much longer.”3 Durham was expecting to find that liberalism and economincs were the cause of the rebellion, however; he found that the rebellion was actually being caused by conflict between the traditional French and modernizing English. In response, Durham proposed that Upper and Lower Canada be united into one province. Although this idea never actually held any significance, it still managed to set a precedent and spark the idea of a possible Confederation.<br> It took nearly 30 years after Durham's report to formulate the British North American Act. On July 1, 1867, the British Colonies of Canada, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick were united to form the Dominion of Canada. This is what is referred to as the Canadian Confederation. This was not a revolution, but rather a calculated political separation. In the decades before 1867, “almost all influential British opinion came to favour the eventual creation of a regional union, [but] in Canada opinion was more divided.”1 Canada knew that they wanted to be their own country, but they were not sure to what level of independence they really wanted. On the other hand, Great Britain wanted to decrease their involvement with overseas colonies as it was becoming increasingly expensive. So, when they heard that Canada wanted independence, they were very eager to make a deal. Canada has always had a primarily resource based economy, so Britain was not ready to let them go completely. Britain wanted to come up with a way in which they could still benefit from the overseas resources, while still giving Canada what they wanted.<br> The British North America Act (BNA) brought upon the new Dominion of Canada a constitution “similar to that of the United Kingdom.”2 Although separated, Britain still had its way of maintaining just enough control of Canada. The executive government of the new dominion was still vested in Queen Victoria and her successors. Canada's new government was formed in British tradition of a parliament and a cabinet. Senators were appointed for life to form the legislature, and representation for the House of Commons was determined by elections.<br> The most important part of the BNA was the new constitution, which outlined the federal and provincial powers. The people were not so worried about all of the little details; they were really just worried about being able to live peacefully the ‘Canadian way.’ One of the lines of the BNA stated that the ultimate goal was peace, order, and good government. Canadians took this little minute detail and lived by it. They even came to brand that as the new Dominions motto.

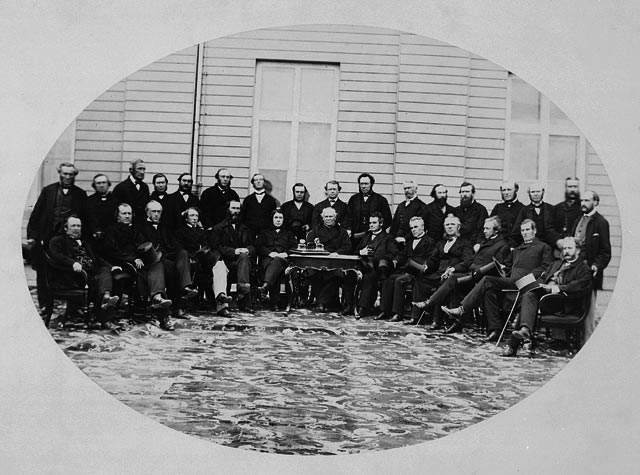

The Delegates of the Provinces and the Quebec Confederation Conference. 27, Oct. 1864.

The Delegates of the Provinces and the Quebec Confederation Conference. 27, Oct. 1864.

1White, W. L. Canadian Confederation: a decision-making analysis. Toronto: Macmillan of Canada, 1979. Page 110.

2McConnell, William H. Commentary on the British North America Act. Toronto: Macmillan of Canada, 1977. Page 7.

3Durham, Lord. Archive.org. Edited by C.P. Lucas. Vol. 3. 3 vols. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1912. Page 127, 128.