The natives of the land come to the mariners, bearing lotus.

What is the lotus of this story? Is it the flower that we would associate it with today?

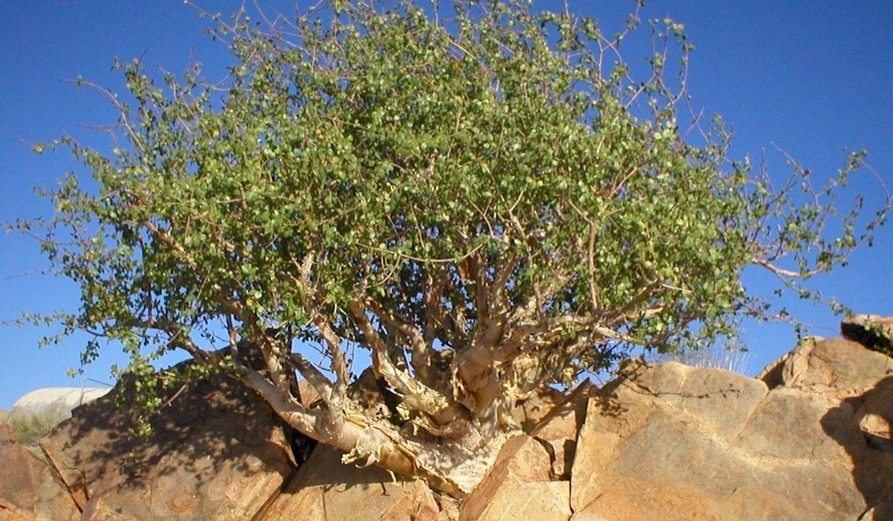

Authors during Homer's time used the term lotus to describe a number of different types of plants: the actual lotus (of which there are different types), jujube, as well as others.

Alexander Pope investigated this same issue: "It has been a question whether it is an herb, a root, or a tree: [Eustathius] is of the opinion that Homer speaks of it as an herb...There is an Egyptian lotos, which, as Herodotus affirms, grows in great abundance along the Nile in the time of its inundations;...The Egyptians dry it in the sun, then take the pulp out of it, which grows like the head of a poppy and bake it like bread;this...agrees likewise" with Homer's description of the lotus.

However, scholars during Pope's time (who Tennyson studied) took the classical works too literally, at times attempting to work with the texts as if they were fact(however it is interesting to note Pope's reference to poppy).

More modern scholars have attempted to discover the answer to this question not by the physical description Homer gave, but by the euphoric characteristics of the plant. They note (as Pope knowingly or unknowingly also did) the similarities to opium (derived from poppy). It is possible that Homer had or heard of an experience with opium, but did not know what it was.

Whatever the true origin of the lotus in this story, Tennyson recognizes the similarities it has with the opium of his day.

Works cited:

Pope, Alexander, and Maynard Mack. The Poems of Alexander Pope. London: Methuen, 1969. Print.

Stevenson, Catherine Barnes. “The Shade of Homer Exorcises the Ghost of De Quincey: Tennyson's "the Lotos-eaters"”. Browning Institute Studies 10 (1982): 117–141.

).

).