Research, data and education products to support you and help you meet your objectives.

ask a question about this.

Research, data and education products to support you and help you meet your objectives.

ask a question about this.

QIIME 2 stores data in a directory structure called an Archive. These archives are zipped to make moving data simple and convenient. The directory structure has a single root directory named with a UUID which serves as the identity of the archive.

If the archive is an artifact, then the payload is determined by the directory format.

In addition to storing data, we can store metadata containing information such as what actions were performed, what versions exist, what references to cite.

In the root of an archive directory, there is a file named metadata.yaml. This file describes the type, the directory format, and repeats the identity of a piece of data. An example of this file: uuid: 45c12936-4b60-484d-bbe1-98ff96bad145 type: FeatureTable[Frequency] format: BIOMV210DirFmt It is possible for format to be set as null in some cases; it means the /data/ directory (described below) does not have a schema. This occurs when the type is set as Visualization (representing a Visualization (Type)).

Following the provenance directory, we see that the provenance structure is repeated within the /provenance/artifacts/ directory. This directory contains the ancestral provenance of all artifacts used up to this point. Because the structure repeats itself, it is possible to create a new provenance directory by simply adding all input artifacts’ /provenance/ directories into a new /provenance/artifacts/ directory. Then the /provenance/artifacts/ directories of the original inputs can be also merged together. Because the directories are named by a UUID, we know the identity of each ancestor, and if seen twice, can simply be ignored. This simplifies the problem of capturing ancestral provenance to one of merging uniquely named file-trees.

As it relates to the archive structure, the /provenance/ directory is designed to be self-contained and self-referential. This means that it duplicates some of the information available in the root of the archive, but this simplifies the code responsible for tracking and reading provenance.

qiime2.core.archive.archiver:_ZipArchive is the structure responsible for managing the contents of a ZIP file (using zipfile:ZipFile).

¶ Every QIIME 2 archive has the following structure: A root directory which is named a standard representation of a UUID (version 4), and a file within that directory named VERSION. The UUID is the identity of the archive, while the VERSION file provides enough detail to determine how to parse the rest of the archive’s structure. Within VERSION the following text will be present: QIIME 2 archive: <integer version> framework: <version string>

Multiplexed reads with the barcodes in the sequence reads can be demultiplexed in QIIME 2 using the q2-cutadapt plugin, which wraps the cutadapt 201 tool.

Illumina sequencing chemistry works by tagging a growing DNA strand with a labelled base to indicate the last nucleotide which was added. 4 different dyes are used for the 4 different bases and imaging the flowcell after each base addition allows the machine to read the most recently added base for each cluster.

There are a couple of different ways in which this problem can manifest itself. Possibly the most obvious is that you can get a huge over-representation of poly-G sequences in reads other than the first read (which is used for cluster detection). From reports we’ve seen this seems to be most prevalent in the first barcode read, but could presumably affect any read where the initial priming of the read failed for any reason.

With the introduction of the NextSeq system Illumina changed the way their image data was acquired so that instead of capturing 4 images per cycle they needed only 2. This speeds up image acquisition significantly but also introduces a problem where high quality calls for G bases can be made where there is actually no signal on the flowcell.

In the standard version of this system used on HiSeq and MiSeq instruments each cycle of chemistry is followed by the acquisition of 4 images of the flowcell, using filters for each of the 4 emission wavelenths of the dyes used. The time taken for this imaging is significant in the overall run time, so it would obviously be beneficial to reduce this. With the introduction of the NextSeq system Illumina introduced a new imaging system which reduced the number of images per cycle from 4 to 2. They did this by using filters which could allow the simultaneous measurement of 2 of the 4 dyes used. By combining the data from these two images they could work out the appropriate base to call.

The problem here though is that there is a fifth base option, which is that there is no signal there to detect. This could happen for a number of reasons: There is no priming site for this read, so no extension is happening. If this happens in the first read then it just won’t detect a cluster, but in subsequent reads the cluster will be assumed to still be present. Enough of the cluster has degraded or stalled that the signal remaining is too faint to detect Something is physically blocking the imaging of the flowcell (air bubbles, dirt on the surface etc etc) In the 4 colour system this extra option is easy to identify since you get no signal from anything, but in the 2 colour system we have a problem, since no signal in either channel is what you’d expect from a G base, so you can’t distinguish no signal from G. What we find therefore on Illumina systems running this chemistry is that we see an over-calling of G bases in these cases, and this can cause problems in downstream processing of data.

There are a few potential strategies for fixing this problem and some of the symptoms will be easier than others. For unprimed reads which are completely polyG then these will probably not affect downstream analyses other than triggering QC alerts, so will have less of an impact once people are aware of their source. For the progressive quality loss the need for a solution is more pressing. Illumina already have a system in place which artificially downweights the quality scores for reads whose quality dips below a certain level. It seems likely that they should be able to adapt their calling software to recognise reads where quality dips to be replaced with high quality poly-G and then artificially downweight the quality scores for the remainder of the read. This same case can probably also be tacked by the authors of trimming programs where they might, for example, provide and option to exempt G calls from the assessment of quality and to trim 3′ Gs from reads as a matter of course. Lessons Learnt You can’t always trust the quality scores coming from sequencers, and if you see odd sequences in your libraries it’s worth investigating them as they may unearth a deeper problem.

A 3’ adapter is assumed to be ligated to the 3’ end of your sequence of interest. When such an adapter is found, the adapter sequence itself and the sequence following it (if there is any) are trimmed.

Instead of removing an adapter from a read, it is also possible to take other actions when an adapter is found by specifying the --action option.

Cutadapt can detect multiple adapter types. 5’ adapters preceed the sequence of interest and 3’ adapters follow it. Further distinctions are made according to where in the read the adapter sequence is allowed to occur.

By default, all adapters are searched error-tolerantly. Adapter sequences may also contain any IUPAC wildcard character (such as N).

it is possible to remove a fixed number of bases from the beginning or end of each read, to remove low-quality bases (quality trimming) from the 3’ and 5’ ends, and to search for adapters also in the reverse-complemented reads.

By using the --cut option or its abbreviation -u, it is possible to unconditionally remove bases from the beginning or end of each read. If the given length is positive, the bases are removed from the beginning of each read. If it is negative, the bases are removed from the end.

Cutadapt searches for the adapter in all reads and removes it when it finds it. Unless you use a filtering option, all reads that were present in the input file will also be present in the output file, some of them trimmed, some of them not. Even reads that were trimmed to a length of zero are output. All of this can be changed with command-line options

The -q (or --quality-cutoff) parameter can be used to trim low-quality ends from reads. If you specify a single cutoff value, the 3’ end of each read is trimmed: cutadapt -q 10 -o output.fastq input.fastq For Illumina reads, this is sufficient as their quality is high at the beginning, but degrades towards the 3’ end.

Quality trimming is done before any adapter trimming.

Some Illumina instruments use a two-color chemistry to encode the four bases. This includes the NextSeq and the NovaSeq. In those instruments, a ‘dark cycle’ (with no detected color) encodes a G. However, dark cycles also occur when when sequencing “falls off” the end of the fragment. The read then contains a run of high-quality, but incorrect “G” calls at its 3’ end. Since the regular quality-trimming algorithm cannot deal with this situation, you need to use the --nextseq-trim option: cutadapt --nextseq-trim=20 -o out.fastq input.fastq This works like regular quality trimming (where one would use -q 20 instead), except that the qualities of G bases are ignored.

A 3’ adapter is a piece of DNA ligated to the 3’ end of the DNA fragment you are interested in. The sequencer starts the sequencing process at the 5’ end of the fragment and sequences into the adapter if the read is long enough. The read that it outputs will then have a part of the adapter in the end. Or, if the adapter was short and the read length quite long, then the adapter will be somewhere within the read, followed by some other bases. For example, assume your fragment of interest is mysequence and the adapter is ADAPTER. Depending on the read length, you will get reads that look like this: mysequen mysequenceADAP mysequenceADAPTER mysequenceADAPTERsomethingelse Use Cutadapt’s -a ADAPTER option to remove this type of adapter. This will be the result: mysequen mysequence mysequence mysequence As this example shows, Cutadapt allows regular 3’ adapters to occur in full anywhere within the read (preceeded and/or succeeded by zero or more bases), and also partially degraded at the 3’ end. Cutadapt deals with 3’ adapters by removing the adapter itself and any sequence that may follow. As a consequence, a sequence that starts with an adapter, like this, will be trimmed to an empty read: ADAPTERsomething By default, empty reads are kept and will appear in the output. If you do not want this, use the --minimum-length/-m filtering option.

Cutadapt finds and removes adapter sequences, primers, poly-A tails and other types of unwanted sequence from your high-throughput sequencing reads. Cleaning your data in this way is often required: Reads from small-RNA sequencing contain the 3’ sequencing adapter because the read is longer than the molecule that is sequenced. Amplicon reads start with a primer sequence. Poly-A tails are useful for pulling out RNA from your sample, but often you don’t want them to be in your reads. Cutadapt helps with these trimming tasks by finding the adapter or primer sequences in an error-tolerant way. It can also modify and filter single-end and paired-end reads in various ways. Adapter sequences can contain IUPAC wildcard characters. Cutadapt can also demultiplex your reads.

Directionality, in molecular biology and biochemistry, is the end-to-end chemical orientation of a single strand of nucleic acid. In a single strand of DNA or RNA, the chemical convention of naming carbon atoms in the nucleotide sugar-ring means that there will be a 5′-end (usually pronounced "five prime end" ), which frequently contains a phosphate group attached to the 5′ carbon of the ribose ring, and a 3′-end (usually pronounced "three prime end"), which typically is unmodified from the ribose -OH substituent. In a DNA double helix, the strands run in opposite directions to permit base pairing between them, which is essential for replication or transcription of the encoded information.

Nucleic acids can only be synthesized in vivo in the 5′-to-3′ direction, as the polymerases that assemble various types of new strands generally rely on the energy produced by breaking nucleoside triphosphate bonds to attach new nucleoside monophosphates to the 3′-hydroxyl (-OH) group, via a phosphodiester bond. The relative positions of structures along a strand of nucleic acid, including genes and various protein binding sites, are usually noted as being either upstream (towards the 5′-end) or downstream (towards the 3′-end).

In molecular biology, complementarity describes a relationship between two structures each following the lock-and-key principle. In nature complementarity is the base principle of DNA replication and transcription as it is a property shared between two DNA or RNA sequences, such that when they are aligned antiparallel to each other, the nucleotide bases at each position in the sequences will be complementary, much like looking in the mirror and seeing the reverse of things. This complementary base pairing allows cells to copy information from one generation to another and even find and repair damage to the information stored in the sequences.

The degree of complementarity between two nucleic acid strands may vary, from complete complementarity (each nucleotide is across from its opposite) to no complementarity (each nucleotide is not across from its opposite) and determines the stability of the sequences to be together. Furthermore, various DNA repair functions as well as regulatory functions are based on base pair complementarity. In biotechnology, the principle of base pair complementarity allows the generation of DNA hybrids between RNA and DNA, and opens the door to modern tools such as cDNA libraries. While most complementarity is seen between two separate strings of DNA or RNA, it is also possible for a sequence to have internal complementarity resulting in the sequence binding to itself in a folded configuration.

With lexical scope, a name always refers to its lexical context. This is a property of the program text and is made independent of the runtime call stack by the language implementation. Because this matching only requires analysis of the static program text, this type of scope is also called static scope. Lexical scope is standard in all ALGOL-based languages such as Pascal, Modula-2 and Ada as well as in modern functional languages such as ML and Haskell. It is also used in the C language and its syntactic and semantic relatives, although with different kinds of limitations. Static scope allows the programmer to reason about object references such as parameters, variables, constants, types, functions, etc. as simple name substitutions. This makes it much easier to make modular code and reason about it, since the local naming structure can be understood in isolation. In contrast, dynamic scope forces the programmer to anticipate all possible execution contexts in which the module's code may be invoked.

Correct implementation of lexical scope in languages with first-class nested functions is not trivial, as it requires each function value to carry with it a record of the values of the variables that it depends on (the pair of the function and this context is called a closure). Depending on implementation and computer architecture, variable lookup may become slightly inefficient[citation needed] when very deeply lexically nested functions are used, although there are well-known techniques to mitigate this.[7][8] Also, for nested functions that only refer to their own arguments and (immediately) local variables, all relative locations can be known at compile time. No overhead at all is therefore incurred when using that type of nested function. The same applies to particular parts of a program where nested functions are not used, and, naturally, to programs written in a language where nested functions are not available (such as in the C language).

as if it was buried 6 days in a row.

Clarify why burying is relevant here.

If you’re still unsure of the rarefaction depth, you can also use the sample summary to look at which samples are lost by supplying sample metadata to the feature table summary.

Show example of this

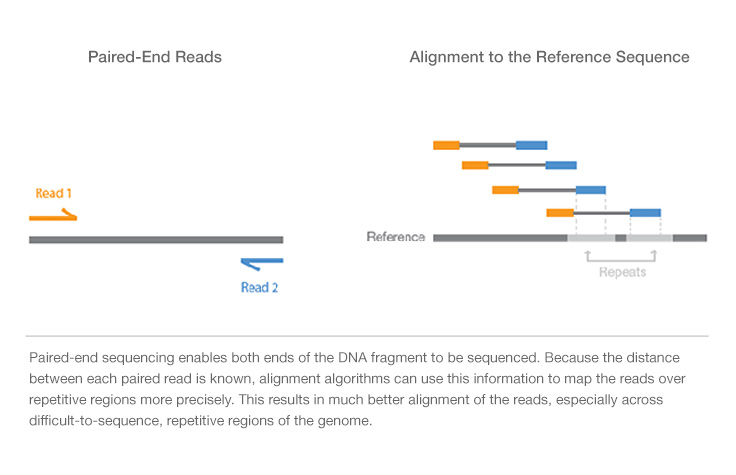

Paired-end sequencing allows users to sequence both ends of a fragment and generate high-quality, alignable sequence data. Paired-end sequencing facilitates detection of genomic rearrangements and repetitive sequence elements, as well as gene fusions and novel transcripts.