Nishga case

The Nishg’a Case, also known as the Calder case named after Nishg’a chief and politician Frank Calder, is a milestone in the fight for aboriginal title in Canada. The colonization of British Columbia forced many First Nations off of their ancestral lands removing the inhabitants’ original status in the 1800’s and early 1900’s as the “The new "assimilationist" paradigm was institutionalized following the transfer of control over Indians to the colonial governments in 1860, and received its organizational form in the reserve and band systems contained in the various Indian acts promulgated by the colonial governments and replicated by the federal government following confederation in 1867” (Crowe, 1979). The Nishg’a were specifically placed in a reserve while receiving money or goods to keep cooperative for many years in the Dominion of Canada. Frank Calder grew up in the midst of the early fight for Nishg’a lands observing his ancestors’ grievances. He was sent to a residential school and studied as the first status native at the University of British Columbia, but after his education and election to the Legislative assembly of British Columbia, Frank Calder’s life’s purpose began.

The Calder case requested the Supreme Court of British Columbia in 1969 to review the fact that the lands of the Nishg’a in the Nass River Valley had never been lawfully extinguished. This case was dismissed in trial immediately, Justice Gould claimed “In his view, whatever territorial rights the Nishg’a had could not have survived the establishment in the colony of British Columbia of general land legislation” (Sanders, 1973). Thomas Berger was employed into the front as The Supreme Court of Canada was next in line to view the Native Claim. In November of 1971, the case was finally heard by the Supreme Court. The Court was benched by seven judges and only six out of the seven confirmed aboriginal title existed. However, the Justices were split evenly if the rights had been extinguished through land laws in the annexation of British Columbia during Confederation. The final ruling of this case was achieved through a technicality from Justice Pigeon (the seventh judge) because the attorney general never gave clear permission for the Nishg’a to sue (Sanders, 1973). This technicality dismissed the case, which resulted in a negative acquisition in legality for the Nishg’a in January of 1973.

The loss for the plaintiffs in the Nishg’a case was not intended by Calder or any of the First Nations observing the fight. However, it served as a catalyst for aboriginal rights in Canadian Law, “following the 1973 Calder decision the constitution became the dominant issue for Canada's Indians, Metis, and Inuit. Through a persistent lobbying effort in the following decade, and thanks to the intervention of a federal election that brought a more sympathetic government to power in Ottawa, Canada's Aboriginal organizations managed to secure a place at the constitutional bargaining table” (Howlett, 1994). With native claims cases growing and gaining legitimacy the Nishg’a’s experience acted as another example of success. The fight was not over, as negotiations between the federal government and the Nishg’a tribal council began in 1976 and lasted until 1999 as the two-negotiated self-government and land claims. Both goals were ratified, and the Nishg’a became the first self-governing tribe in British Columbia.

Sanders, Douglas. The Nishga Case. Vancouver: 1973.

Caption: Frank Calder, Nishg'a Chief

Caption: Frank Calder, Nishg'a Chief

Source: The Canadian Encyclopedia http://ojs.library.ubc.ca/index.php/bcstudies/article/viewFile/782/824 Howlett, Michael. “Policy paradigms and policy change: Lessons from the old and new Canadian policies towards aboriginal peoples”. Policy Studies Journal, (Winter 1994). https://search.proquest.com/docview/210555691?OpenUrlRefId=info:xri/sid:wcdiscovery&accountid=9784 Crowe, Keith. “A Summary of Northern Native Claims in Canada”: The Process and Progress of Negotiations. Études/Inuit/Studies3, no.1 (1979): 31-39. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42869300

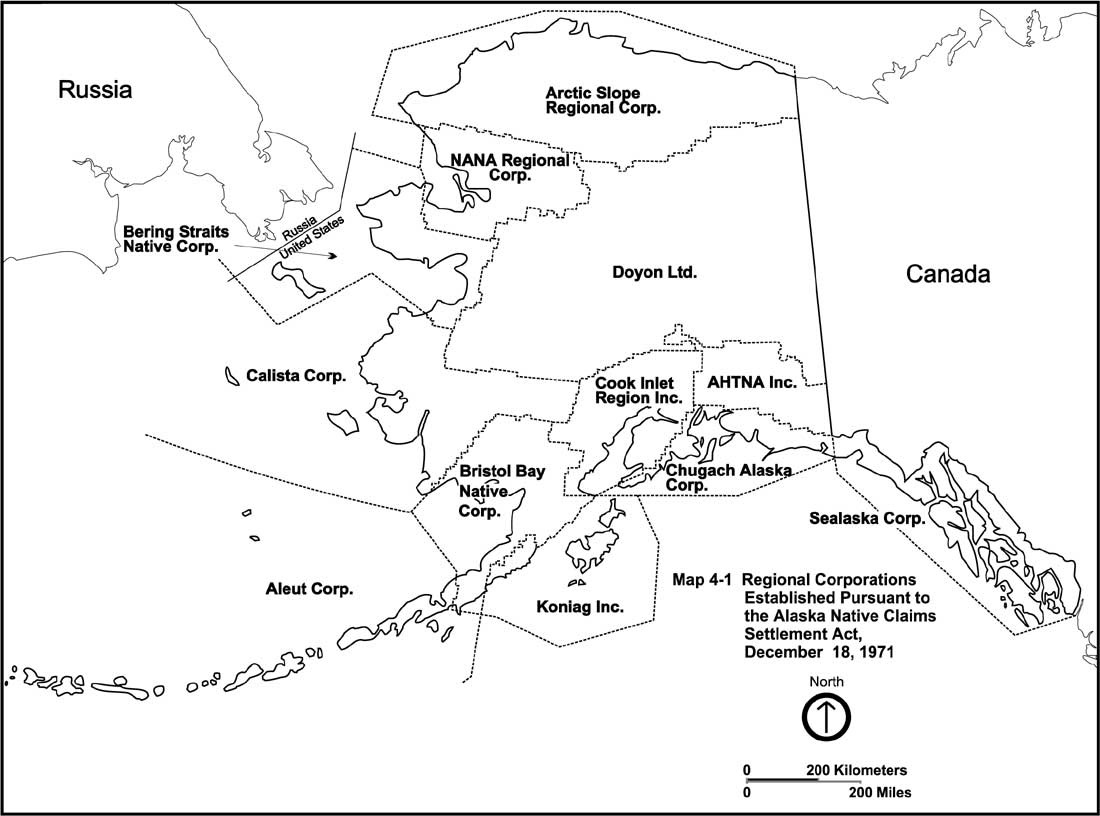

Caption: Map of Regional Corporations

Source: US National Park Service

Caption: Map of Regional Corporations

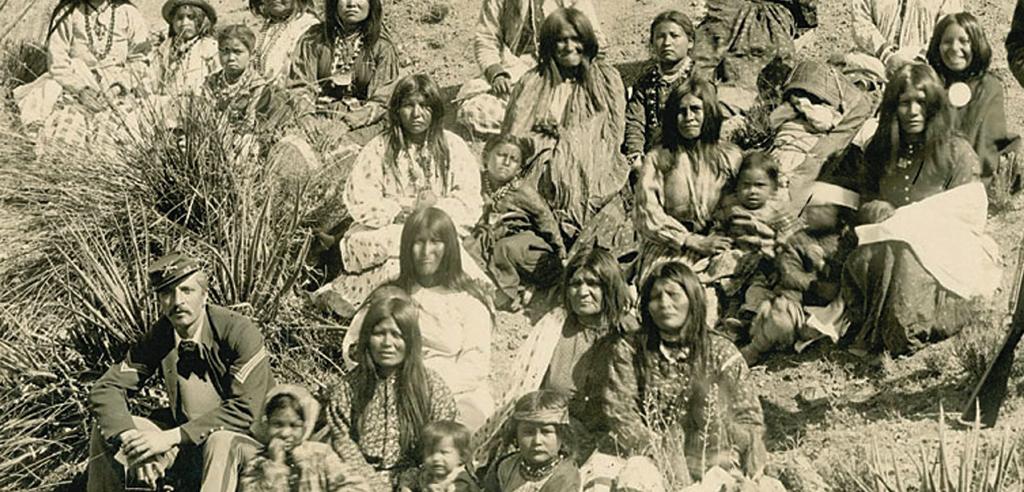

Source: US National Park Service Caption: Forced Indian Removal

Sourece: Equal Justice Initiative

Caption: Forced Indian Removal

Sourece: Equal Justice Initiative