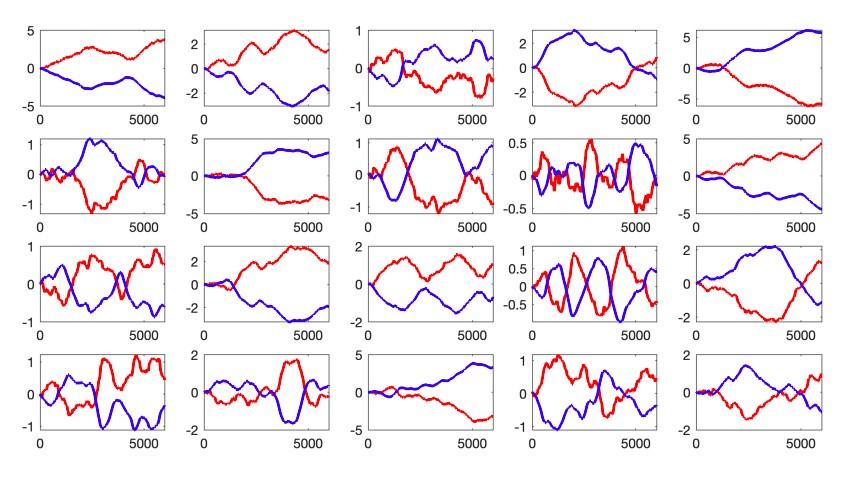

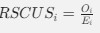

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Here I submit my previous review and a great deal of additional information following on from the initial review and the response by the authors.

* Initial Review *

Assessment:

This manuscript is based upon the unprecedented identification of an apparently highly unusual trigeminal nuclear organization within the elephant brainstem, related to a large trigeminal nerve in these animals. The apparently highly specialized elephant trigeminal nuclear complex identified in the current study has been classified as the inferior olivary nuclear complex in four previous studies of the elephant brainstem. The entire study is predicated upon the correct identification of the trigeminal sensory nuclear complex and the inferior olivary nuclear complex in the elephant, and if this is incorrect, then the remainder of the manuscript is merely unsupported speculation. There are many reasons indicating that the trigeminal nuclear complex is misidentified in the current study, rendering the entire study, and associated speculation, inadequate at best, and damaging in terms of understanding elephant brains and behaviour at worst.

Original Public Review:

The authors describe what they assert to be a very unusual trigeminal nuclear complex in the brainstem of elephants, and based on this, follow with many speculations about how the trigeminal nuclear complex, as identified by them, might be organized in terms of the sensory capacity of the elephant trunk.<br />

The identification of the trigeminal nuclear complex/inferior olivary nuclear complex in the elephant brainstem is the central pillar of this manuscript from which everything else follows, and if this is incorrect, then the entire manuscript fails, and all the associated speculations become completely unsupported.

The authors note that what they identify as the trigeminal nuclear complex has been identified as the inferior olivary nuclear complex by other authors, citing Shoshani et al. (2006; 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2006.03.016) and Maseko et al (2013; 10.1159/000352004), but fail to cite either Verhaart and Kramer (1958; PMID 13841799) or Verhaart (1962; 10.1515/9783112519882-001). These four studies are in agreement, but the current study differs.

Let's assume for the moment that the four previous studies are all incorrect and the current study is correct. This would mean that the entire architecture and organization of the elephant brainstem is significantly rearranged in comparison to ALL other mammals, including humans, previously studied (e.g. Kappers et al. 1965, The Comparative Anatomy of the Nervous System of Vertebrates, Including Man, Volume 1 pp. 668-695) and the closely related manatee (10.1002/ar.20573). This rearrangement necessitates that the trigeminal nuclei would have had to "migrate" and shorten rostrocaudally, specifically and only, from the lateral aspect of the brainstem where these nuclei extend from the pons through to the cervical spinal cord (e.g. the Paxinos and Watson rat brain atlases), the to the spatially restricted ventromedial region of specifically and only the rostral medulla oblongata. According to the current paper the inferior olivary complex of the elephant is very small and located lateral to their trigeminal nuclear complex, and the region from where the trigeminal nuclei are located by others appears to be just "lateral nuclei" with no suggestion of what might be there instead.

Such an extraordinary rearrangement of brainstem nuclei would require a major transformation in the manner in which the mutations, patterning, and expression of genes and associated molecules during development occur. Such a major change is likely to lead to lethal phenotypes, making such a transformation extremely unlikely. Variations in mammalian brainstem anatomy are most commonly associated with quantitative changes rather than qualitative changes (10.1016/B978-0-12-804042-3.00045-2).

The impetus for the identification of the unusual brainstem trigeminal nuclei in the current study rests upon a previous study from the same laboratory (10.1016/j.cub.2021.12.051) that estimated that the number of axons contained in the infraorbital branch of the trigeminal nerve that innervate the sensory surfaces of the trunk is approximately 400 000. Is this number unusual? In a much smaller mammal with a highly specialized trigeminal system, the platypus, the number of axons innervating the sensory surface of the platypus bill skin comes to 1 344 000 (10.1159/000113185). Yet, there is no complex rearrangement of the brainstem trigeminal nuclei in the brain of the developing or adult platypus (Ashwell, 2013, Neurobiology of Monotremes), despite the brainstem trigeminal nuclei being very large in the platypus (10.1159/000067195). Even in other large-brained mammals, such as large whales that do not have a trunk, the number of axons in the trigeminal nerve ranges between 400,000 and 500,000 (10.1007/978-3-319-47829-6_988-1). The lack of comparative support for the argument forwarded in the previous and current study from this laboratory, and that the comparative data indicates that the brainstem nuclei do not change in the manner suggested in the elephant, argues against the identification of the trigeminal nuclei as outlined in the current study. Moreover, the comparative studies undermine the prior claim of the authors, informing the current study, that "the elephant trigeminal ganglion ... point to a high degree of tactile specialization in elephants" (10.1016/j.cub.2021.12.051). While clearly the elephant has tactile sensitivity in the trunk, it is questionable as to whether what has been observed in elephants is indeed "truly extraordinary".

But let's look more specifically at the justification outlined in the current study to support their identification of the unusually located trigeminal sensory nuclei of the brainstem.

(1) Intense cytochrome oxidase reactivity<br />

(2) Large size of the putative trunk module<br />

(3) Elongation of the putative trunk module<br />

(4) Arrangement of these putative modules correspond to elephant head anatomy<br />

(5) Myelin stripes within the putative trunk module that apparently match trunk folds<br />

(6) Location apparently matches other mammals<br />

(7) Repetitive modular organization apparently similar to other mammals.<br />

(8) The inferior olive described by other authors lacks the lamellated appearance of this structure in other mammals

Let's examine these justifications more closely.

(1) Cytochrome oxidase histochemistry is typically used as an indicative marker of neuronal energy metabolism. The authors indicate, based on the "truly extraordinary" somatosensory capacities of the elephant trunk, that any nuclei processing this tactile information should be highly metabolically active, and thus should react intensely when stained for cytochrome oxidase. We are told in the methods section that the protocols used are described by Purkart et al (2022) and Kaufmann et al (2022). In neither of these cited papers is there any description, nor mention, of the cytochrome oxidase histochemistry methodology, thus we have no idea of how this histochemical staining was done. In order to obtain the best results for cytochrome oxidase histochemistry, the tissue is either processed very rapidly after buffer perfusion to remove blood or in recently perfusion-fixed tissue (e.g., 10.1016/0165-0270(93)90122-8). Given: (1) the presumably long post-mortem interval between death and fixation - "it often takes days to dissect elephants"; (2) subsequent fixation of the brains in 4% paraformaldehyde for "several weeks"; (3) The intense cytochrome oxidase reactivity in the inferior olivary complex of the laboratory rat (Gonzalez-Lima, 1998, Cytochrome oxidase in neuronal metabolism and Alzheimer's diseases); and (4) The lack of any comparative images from other stained portions of the elephant brainstem; it is difficult to support the justification as forwarded by the authors. It is likely that the histochemical staining observed is background reactivity from the use of diaminobenzidine in the staining protocol. Thus, this first justification is unsupported.<br />

Justifications (2), (3), and (4) are sequelae from justification (1). In this sense, they do not count as justifications, but rather unsupported extensions.

(4) and (5) These are interesting justifications, as the paper has clear internal contradictions, and (5) is a sequelae of (4). The reader is led to the concept that the myelin tracts divide the nuclei into sub-modules that match the folding of the skin on the elephant trunk. One would then readily presume that these myelin tracts are in the incoming sensory axons from the trigeminal nerve. However, the authors note that this is not the case: "Our observations on trunk module myelin stripes are at odds with this view of myelin. Specifically, myelin stripes show no tapering (which we would expect if axons divert off into the tissue). More than that, there is no correlation between myelin stripe thickness (which presumably correlates with axon numbers) and trigeminal module neuron numbers. Thus, there are numerous myelinated axons, where we observe few or no trigeminal neurons. These observations are incompatible with the idea that myelin stripes form an axonal 'supply' system or that their prime function is to connect neurons. What do myelin stripe axons do, if they do not connect neurons? We suggest that myelin stripes serve to separate rather than connect neurons." So, we are left with the observation that the myelin stripes do not pass afferent trigeminal sensory information from the "truly extraordinary" trunk skin somatic sensory system, and rather function as units that separate neurons - but to what end? It appears that the myelin stripes are more likely to be efferent axonal bundles leaving the nuclei (to form the olivocerebellar tract). This justification is unsupported.

(6) The authors indicate that the location of these nuclei matches that of the trigeminal nuclei in other mammals. This is not supported in any way. In ALL other mammals in which the trigeminal nuclei of the brainstem have been reported they are found in the lateral aspect of the brainstem, bordered laterally by the spinal trigeminal tract. This is most readily seen and accessible in the Paxinos and Watson rat brain atlases. The authors indicate that the trigeminal nuclei are medial to the facial nerve nucleus, but in every other species, the trigeminal sensory nuclei are found lateral to the facial nerve nucleus. This is most salient when examining a close relative, the manatee (10.1002/ar.20573), where the location of the inferior olive and the trigeminal nuclei matches that described by Maseko et al (2013) for the African elephant. This justification is not supported.

(7) The dual to quadruple repetition of rostro-caudal modules within the putative trigeminal nucleus as identified by the authors relies on the fact that in the neurotypical mammal, there are several trigeminal sensory nuclei arranged in a column running from the pons to the cervical spinal cord, these include (nomenclature from Paxinos and Watson in roughly rostral to caudal order) the Pr5VL, Pr5DM, Sp5O, Sp5I, and Sp5C. But, these nuclei are all located far from the midline and lateral to the facial nerve nucleus, unlike what the authors describe in the elephants. These rostrocaudal modules are expanded upon in Figure 2, and it is apparent from what is shown that the authors are attributing other brainstem nuclei to the putative trigeminal nuclei to confirm their conclusion. For example, what they identify as the inferior olive in figure 2D is likely the lateral reticular nucleus as identified by Maseko et al (2013). This justification is not supported.

(8) In primates and related species, there is a distinct banded appearance of the inferior olive, but what has been termed the inferior olive in the elephant by other authors does not have this appearance, rather, and specifically, the largest nuclear mass in the region (termed the principal nucleus of the inferior olive by Maseko et al, 2013, but Pr5, the principal trigeminal nucleus in the current paper) overshadows the partial banded appearance of the remaining nuclei in the region (but also drawn by the authors of the current paper). Thus, what is at debate here is whether the principal nucleus of the inferior olive can take on a nuclear shape rather than evince a banded appearance. The authors of this paper use this variance as justification that this cluster of nuclei could not possibly be the inferior olive. Such a "semi-nuclear/banded" arrangement of the inferior olive is seen in, for example, giraffe (10.1016/j.jchemneu.2007.05.003), domestic dog, polar bear, and most specifically the manatee (a close relative of the elephant) (brainmuseum.org; 10.1002/ar.20573). This justification is not supported.

Thus, all the justifications forwarded by the authors are unsupported. Based on methodological concerns, prior comparative mammalian neuroanatomy, and prior studies in the elephant and closely related species, the authors fail to support their notion that what was previously termed the inferior olive in the elephant is actually the trigeminal sensory nuclei. Given this failure, the justifications provided above that are sequelae also fail. In this sense, the entire manuscript and all the sequelae are not supported.

What the authors have not done is to trace the pathway of the large trigeminal nerve in the elephant brainstem, as was done by Maseko et al (2013), which clearly shows the internal pathways of this nerve, from the branch that leads to the fifth mesencephalic nucleus adjacent to the periventricular grey matter, through to the spinal trigeminal tract that extends from the pons to the spinal cord in a manner very similar to all other mammals. Nor have they shown how the supposed trigeminal information reaches the putative trigeminal nuclei in the ventromedial rostral medulla oblongata. These are but two examples of many specific lines of evidence that would be required to support their conclusions. Clearly tract tracing methods, such as cholera toxin tracing of peripheral nerves cannot be done in elephants, thus the neuroanatomy must be done properly and with attention to detail to support the major changes indicated by the authors.

So what are these "bumps" in the elephant brainstem?

Four previous authors indicate that these bumps are the inferior olivary nuclear complex. Can this be supported?

The inferior olivary nuclear complex acts "as a relay station between the spinal cord (n.b. trigeminal input does reach the spinal cord via the spinal trigeminal tract) and the cerebellum, integrating motor and sensory information to provide feedback and training to cerebellar neurons" (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542242/). The inferior olivary nuclear complex is located dorsal and medial to the pyramidal tracts (which were not labelled in the current study by the authors but are clearly present in Fig. 1C and 2A) in the ventromedial aspect of the rostral medulla oblongata. This is precisely where previous authors have identified the inferior olivary nuclear complex and what the current authors assign to their putative trigeminal nuclei. The neurons of the inferior olivary nuclei project, via the olivocerebellar tract to the cerebellum to terminate in the climbing fibres of the cerebellar cortex.

Elephants have the largest (relative and absolute) cerebellum of all mammals (10.1002/ar.22425), this cerebellum contains 257 x109 neurons (10.3389/fnana.2014.00046; three times more than the entire human brain, 10.3389/neuro.09.031.2009). Each of these neurons appears to be more structurally complex than the homologous neurons in other mammals (10.1159/000345565; 10.1007/s00429-010-0288-3). In the African elephant, the neurons of the inferior olivary nuclear complex are described by Maseko et al (2013) as being both calbindin and calretinin immunoreactive. Climbing fibres in the cerebellar cortex of the African elephant are clearly calretinin immunopositive and also are likely to contain calbindin (10.1159/000345565). Given this, would it be surprising that the inferior olivary nuclear complex of the elephant is enlarged enough to create a very distinct bump in exactly the same place where these nuclei are identified in other mammals?

What about the myelin stripes? These are most likely to be the origin of the olivocerebellar tract and probably only have a coincidental relationship to the trunk. Thus, given what we know, the inferior olivary nuclear complex as described in other studies, and the putative trigeminal nuclear complex as described in the current study, is the elephant inferior olivary nuclear complex. It is not what the authors believe it to be, and they do not provide any evidence that discounts the previous studies. The authors are quite simply put, wrong. All the speculations that flow from this major neuroanatomical error are therefore science fiction rather than useful additions to the scientific literature.

What do the authors actually have?<br />

The authors have interesting data, based on their Golgi staining and analysis, of the inferior olivary nuclear complex in the elephant.

* Review of Revised Manuscript *

Assessment:

There is a clear dichotomy between the authors and this reviewer regarding the identification of specific structures, namely the inferior olivary nuclear complex and the trigeminal nuclear complex, in the brainstem of the elephant. The authors maintain the position that in the elephant alone, irrespective of all the published data on other mammals and previously published data on the elephant brainstem, these two nuclear complexes are switched in location. The authors maintain that their interpretation is correct, but this reviewer maintains that this interpretation is erroneous. The authors expressed concern that the remainder of the paper was not addressed by the reviewer, but the reviewer maintains that these sequelae to the misidentification of nuclear complexes in the elephant brainstem render any of these speculations irrelevant as the critical structures are incorrectly identified. It is this reviewer's opinion that this paper is incorrect. I provide a lot of detail below in order to provide support to the opinion I express.

Public Review of Current Submission:

As indicated in my previous review of this manuscript (see above), it is my opinion that the authors have misidentified, and indeed switched, the inferior olivary nuclear complex (IO) and the trigeminal nuclear complex (Vsens). It is this specific point only that I will address in this second review, as this is the crucial aspect of this paper - if the identification of these nuclear complexes in the elephant brainstem by the authors is incorrect, the remainder of the paper does not have any scientific validity.

The authors, in their response to my initial review, claim that I "bend" the comparative evidence against them. They further claim that as all other mammalian species exhibit a "serrated" appearance of the inferior olive, and as the elephant does not exhibit this appearance, what was previously identified as the inferior olive is actually the trigeminal nucleus and vice versa.

For convenience, I will refer to IOM and VsensM as the identification of these structures according to Maseko et al (2013) and other authors and will use IOR and VsensR to refer to the identification forwarded in the study under review.<br />

The IOM/VsensR certainly does not have a serrated appearance in elephants. Indeed, from the plates supplied by the authors in response (Referee Fig. 2), the cytochrome oxidase image supplied and the image from Maseko et al (2013) shows a very similar appearance. There is no doubt that the authors are identifying structures that closely correspond to those provided by Maseko et al (2013). It is solely a contrast in what these nuclear complexes are called and the functional sequelae of the identification of these complexes (are they related to the trunk sensation or movement controlled by the cerebellum?) that is under debate.

Elephants are part of the Afrotheria, thus the most relevant comparative data to resolve this issue will be the identification of these nuclei in other Afrotherian species. Below I provide images of these nuclear complexes, labelled in the standard nomenclature, across several Afrotherian species.

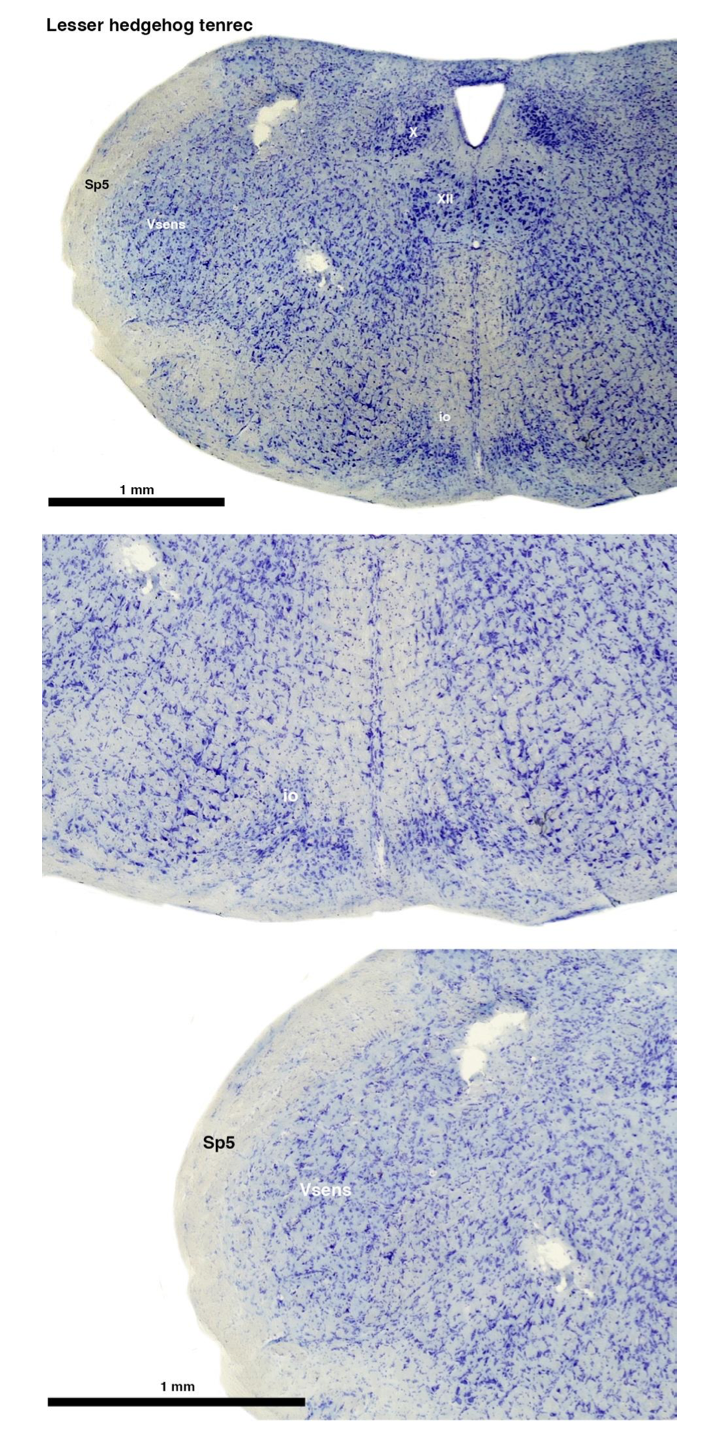

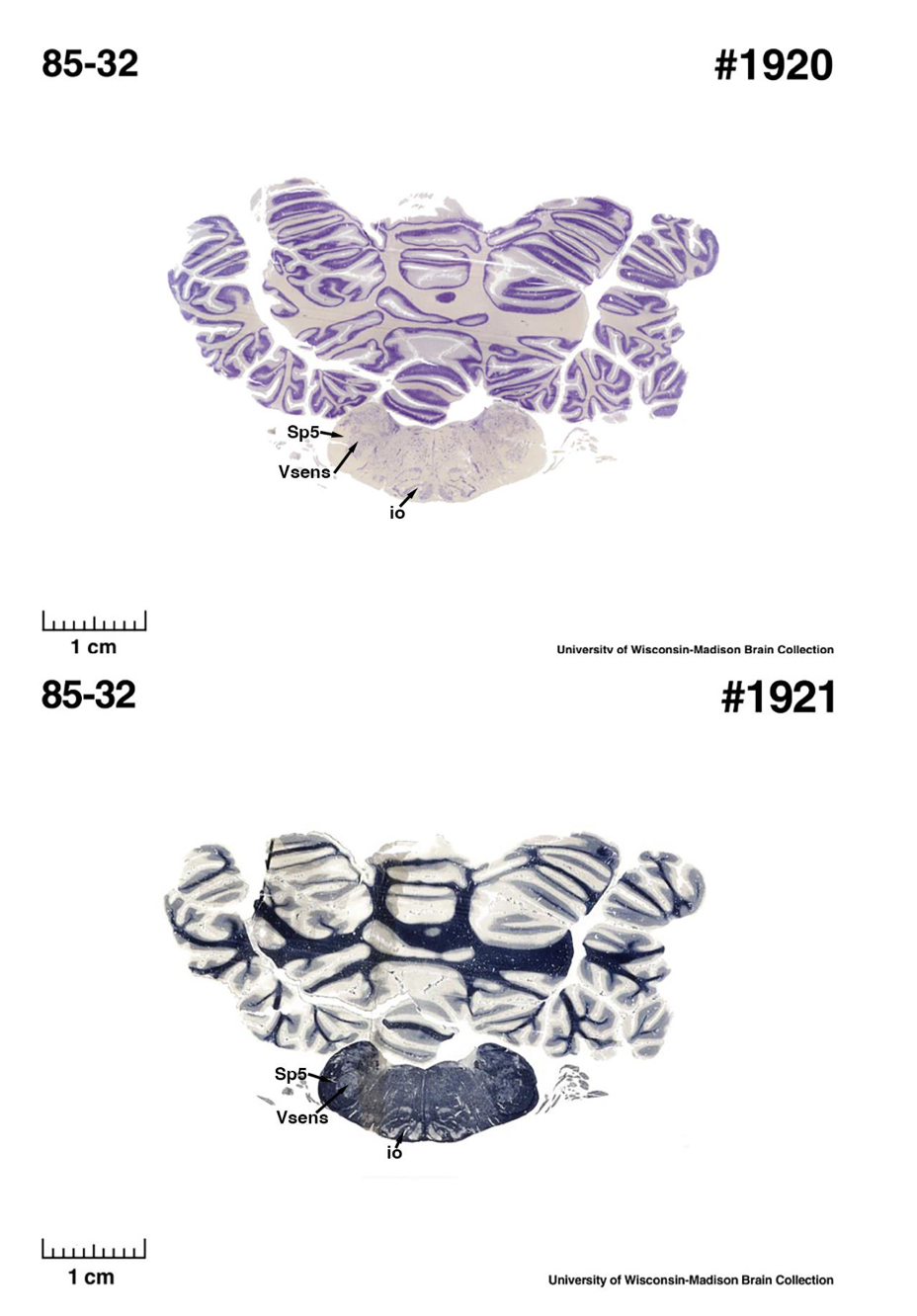

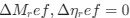

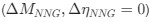

(A) Lesser hedgehog tenrec (Echinops telfairi)

Tenrecs brains are the most intensively studied of the Afrotherian brains, these extensive neuroanatomical studies were undertaken primarily by Heinz Künzle. Below I append images (coronal sections stained with cresol violet) of the IO and Vsens (labelled in the standard mammalian manner) in the lesser hedgehog tenrec. It should be clear that the inferior olive is located in the ventral midline of the rostral medulla oblongata (just like the rat) and that this nucleus is not distinctly serrated. The Vsens is located in the lateral aspect of the medulla skirted laterally by the spinal trigeminal tract (Sp5). These images and the labels indicating structures correlate precisely with that provided by Künzle (1997, 10.1016/S0168- 0102(97)00034-5), see his Figure 1K,L. Thus, in the first case of a related species, there is no serrated appearance of the inferior olive, the location of the inferior olive is confirmed through connectivity with the superior colliculus (a standard connection in mammals) by Künzle (1997), and the location of Vsens is what is considered to be typical for mammals. This is in agreement with the authors, as they propose that ONLY the elephants show the variations they report.

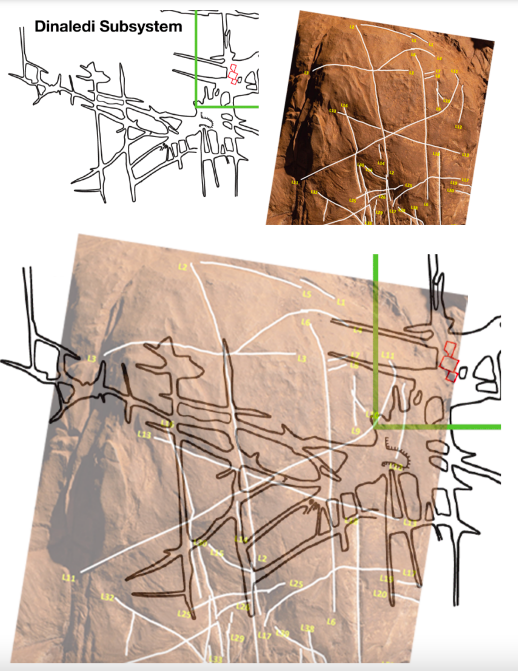

Review image 1.

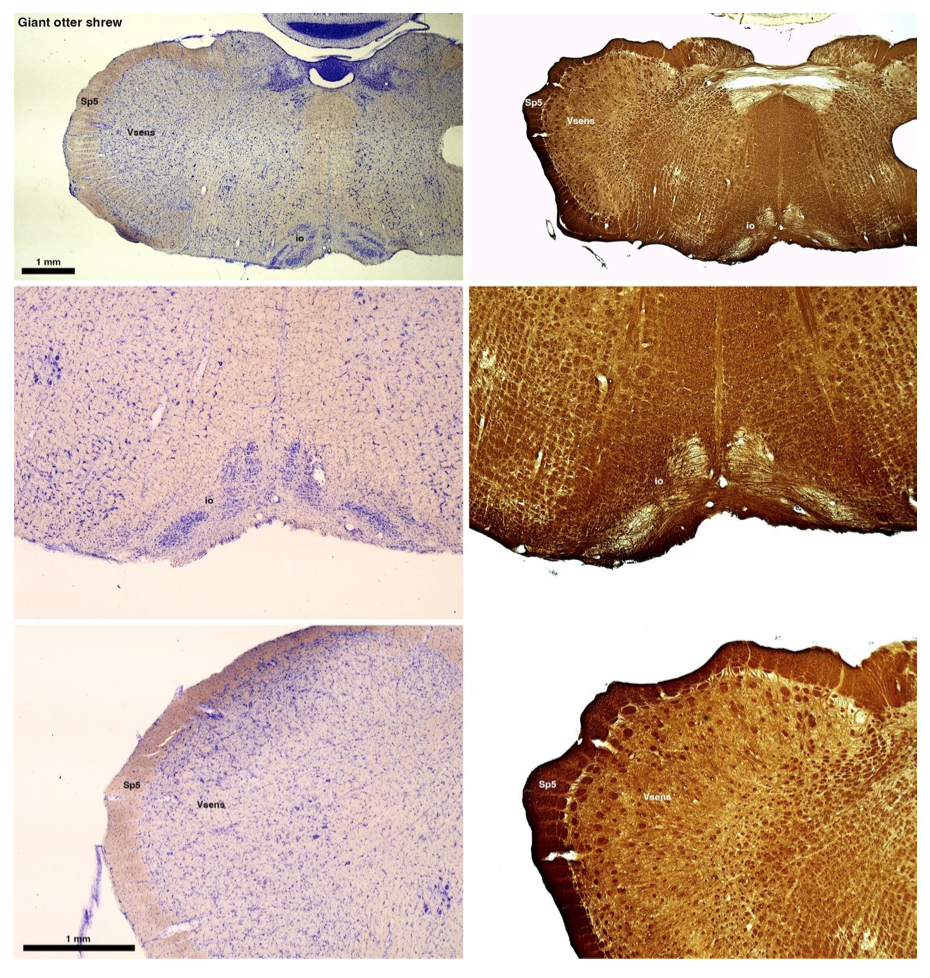

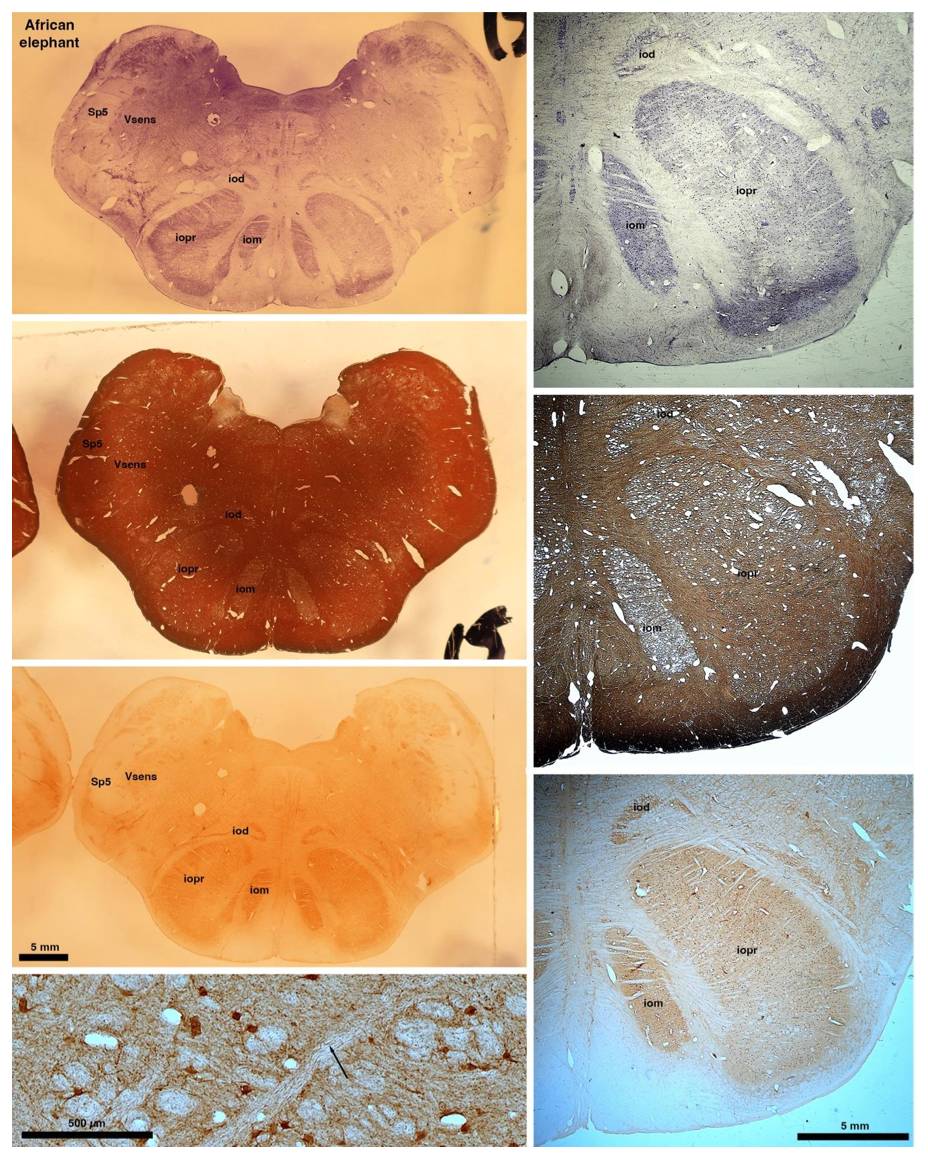

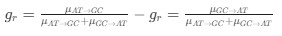

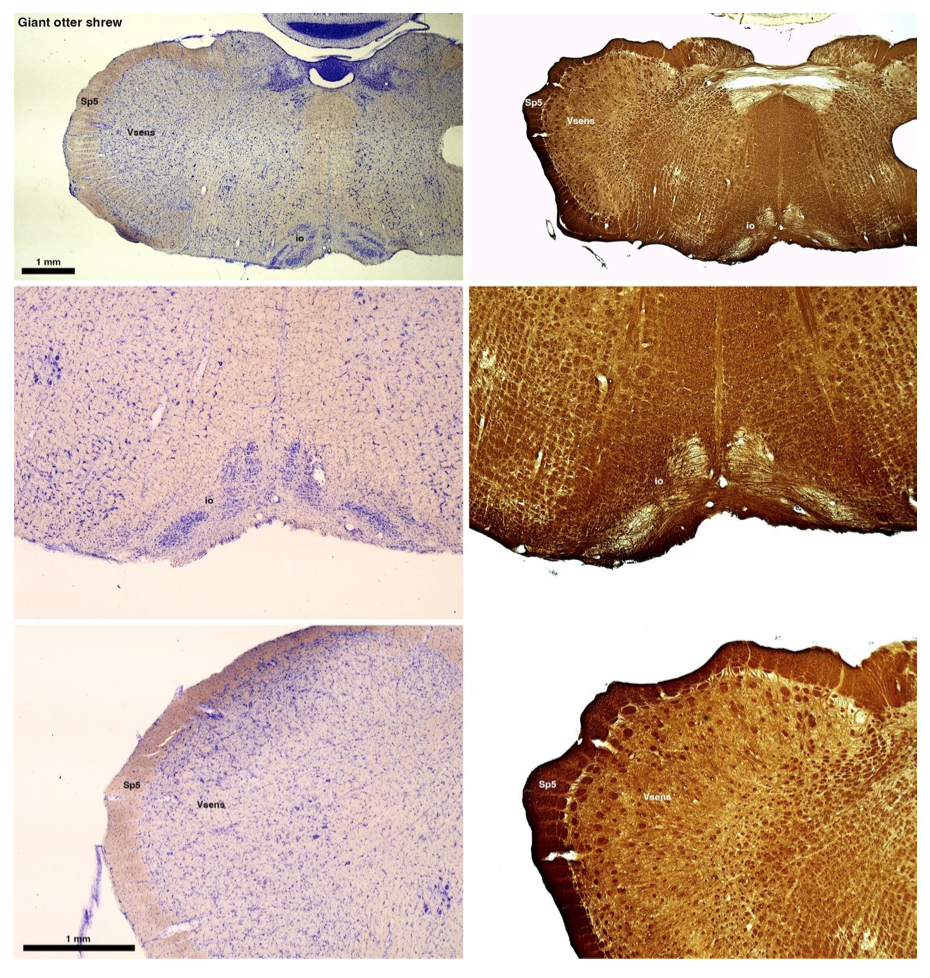

(B) Giant otter shrew (Potomogale velox)

The otter shrews are close relatives of the Tenrecs. Below I append images of cresyl violet (left column) and myelin (right column) stained coronal sections through the brainstem with the IO, Vsens and Sp5 labelled as per standard mammalian anatomy. Here we see hints of the serration of the IO as defined by the authors, but we also see many myelin stripes across the IO. Vsens is located laterally and skirted by the Sp5. This is in agreement with the authors, as they propose that ONLY the elephants show the variations they report.

Review image 2.

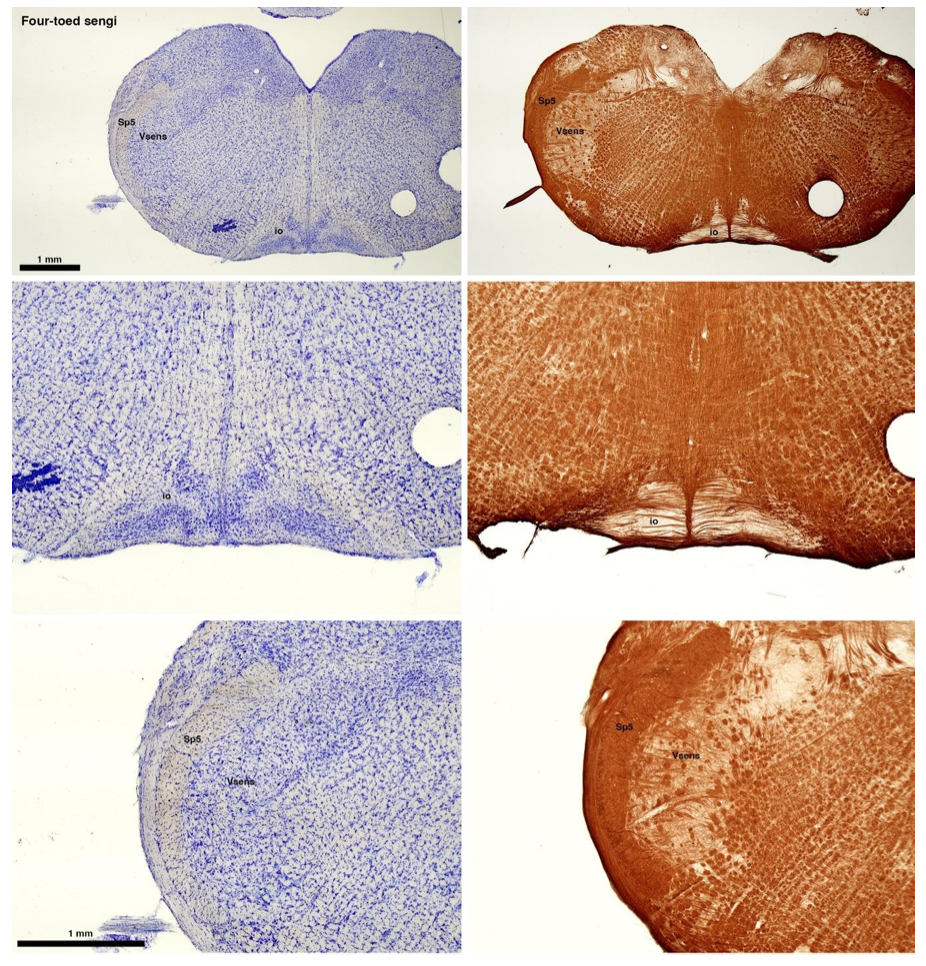

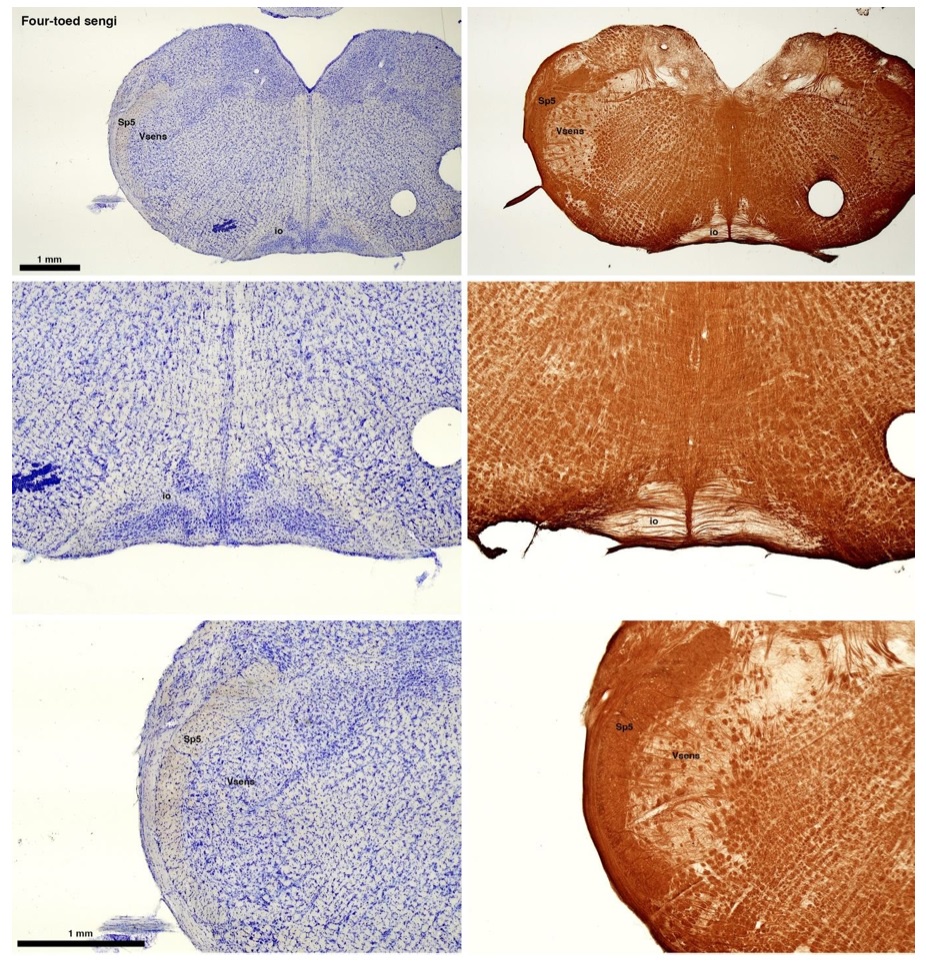

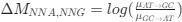

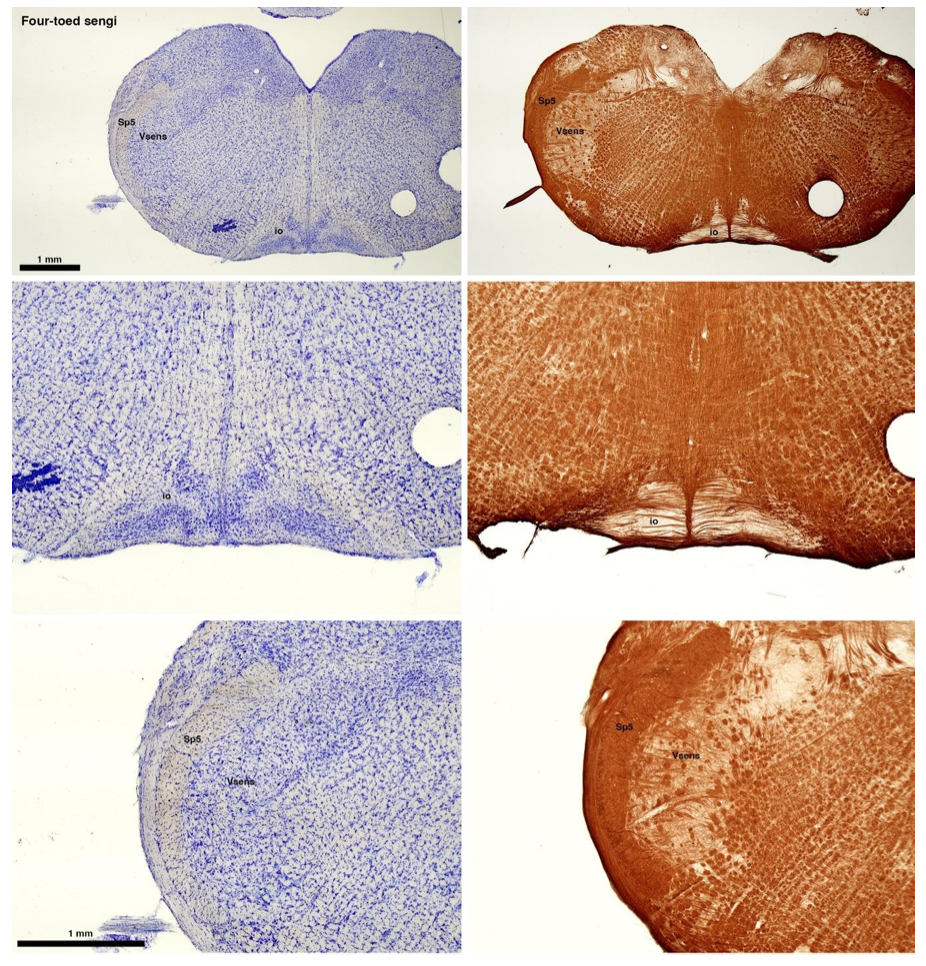

(C) Four-toed sengi (Petrodromus tetradactylus)

The sengis are close relatives of the Tenrecs and otter shrews, these three groups being part of the Afroinsectiphilia, a distinct branch of the Afrotheria. Below I append images of cresyl violet (left column) and myelin (right column) stained coronal sections through the brainstem with the IO, Vsens and Sp5 labelled as per standard mammalian anatomy. Here we see vague hints of the serration of the IO (as defined by the authors), and we also see many myelin stripes across the IO. Vsens is located laterally and skirted by the Sp5. This is in agreement with the authors, as they propose that ONLY the elephants show the variations they report.

Review image 3.

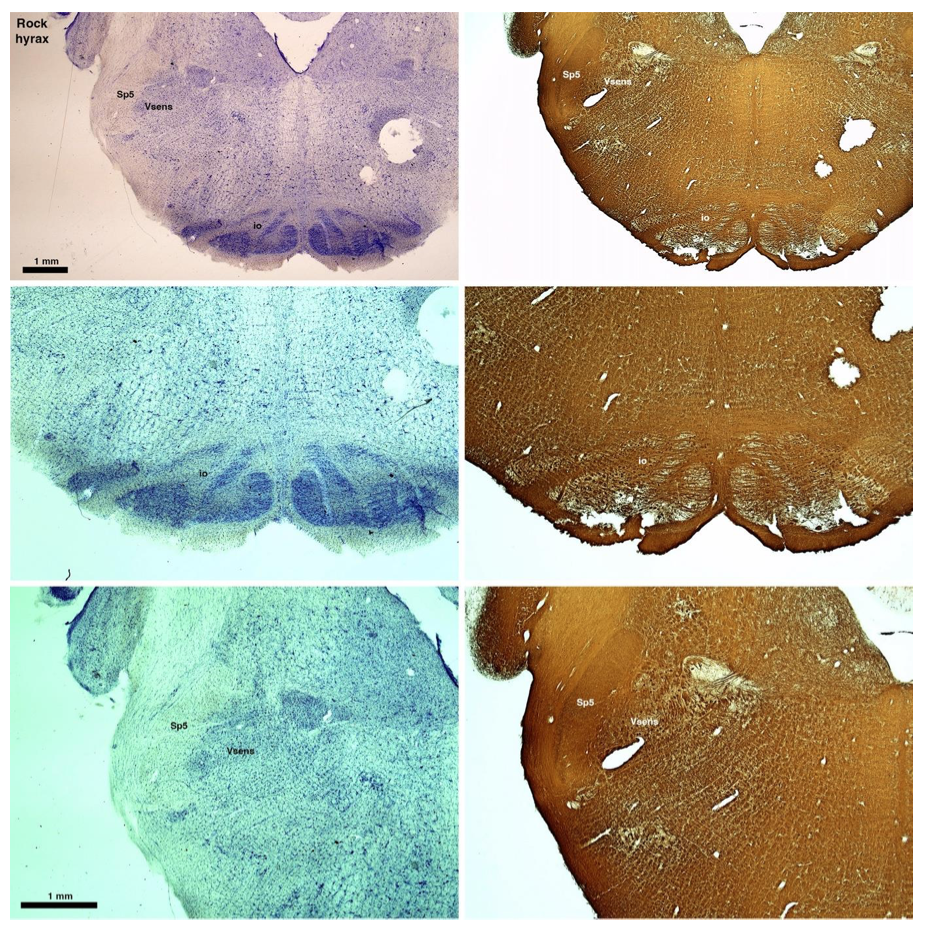

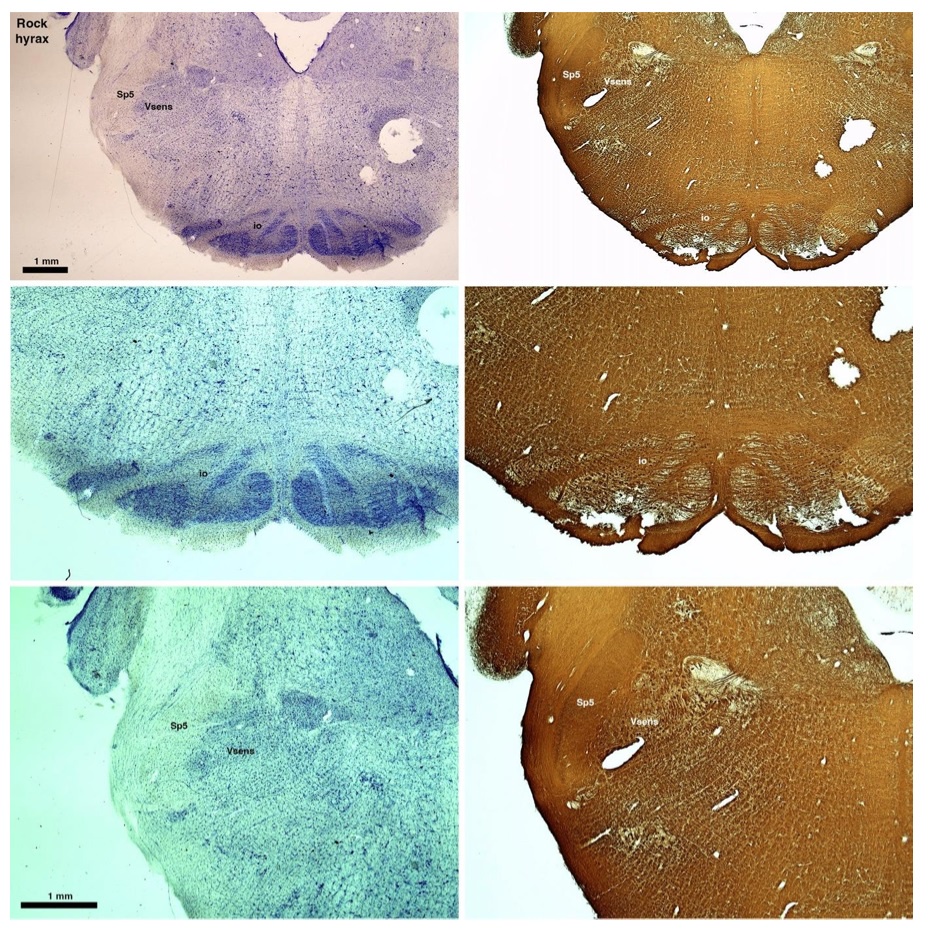

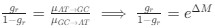

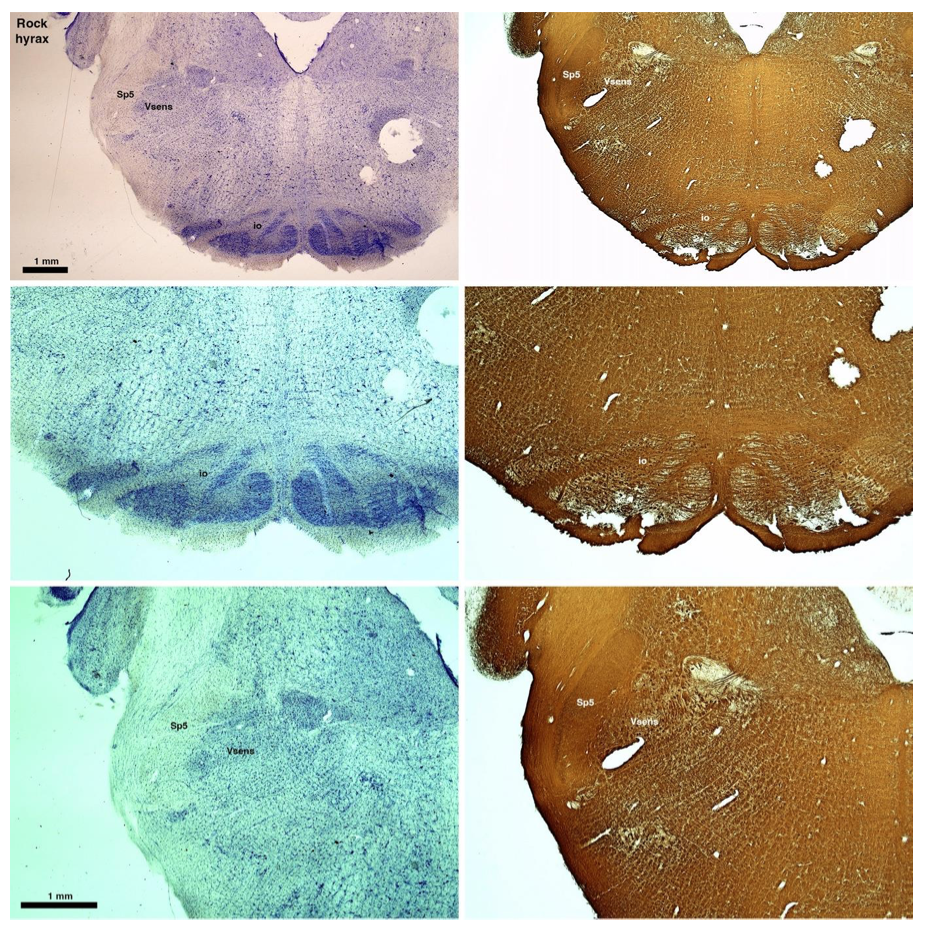

(D) Rock hyrax (Procavia capensis)

The hyraxes, along with the sirens and elephants form the Paenungulata branch of the Afrotheria. Below I append images of cresyl violet (left column) and myelin (right column) stained coronal sections through the brainstem with the IO, Vsens and Sp5 labelled as per the standard mammalian anatomy. Here we see hints of the serration of the IO (as defined by the authors), but we also see evidence of a more "bulbous" appearance of subnuclei of the IO (particularly the principal nucleus), and we also see many myelin stripes across the IO. Vsens is located laterally and skirted by the Sp5. This is in agreement with the authors, as they propose that ONLY the elephants show the variations they report.

Review image 4.

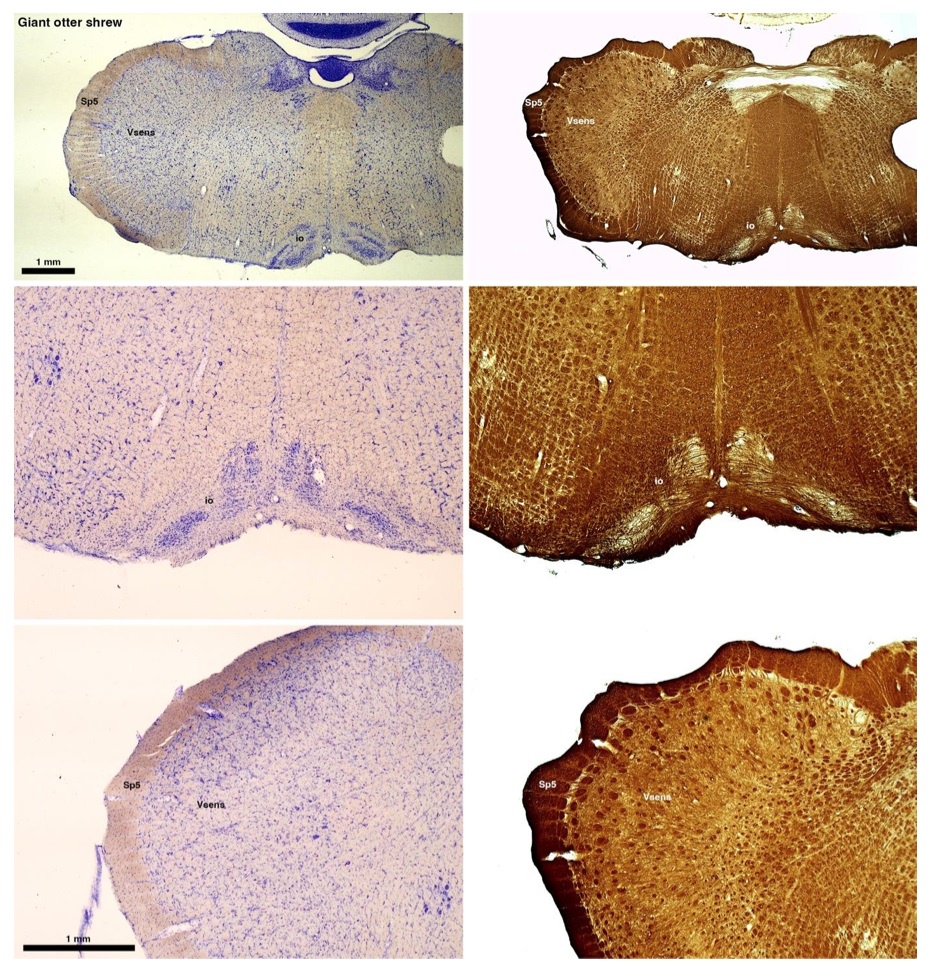

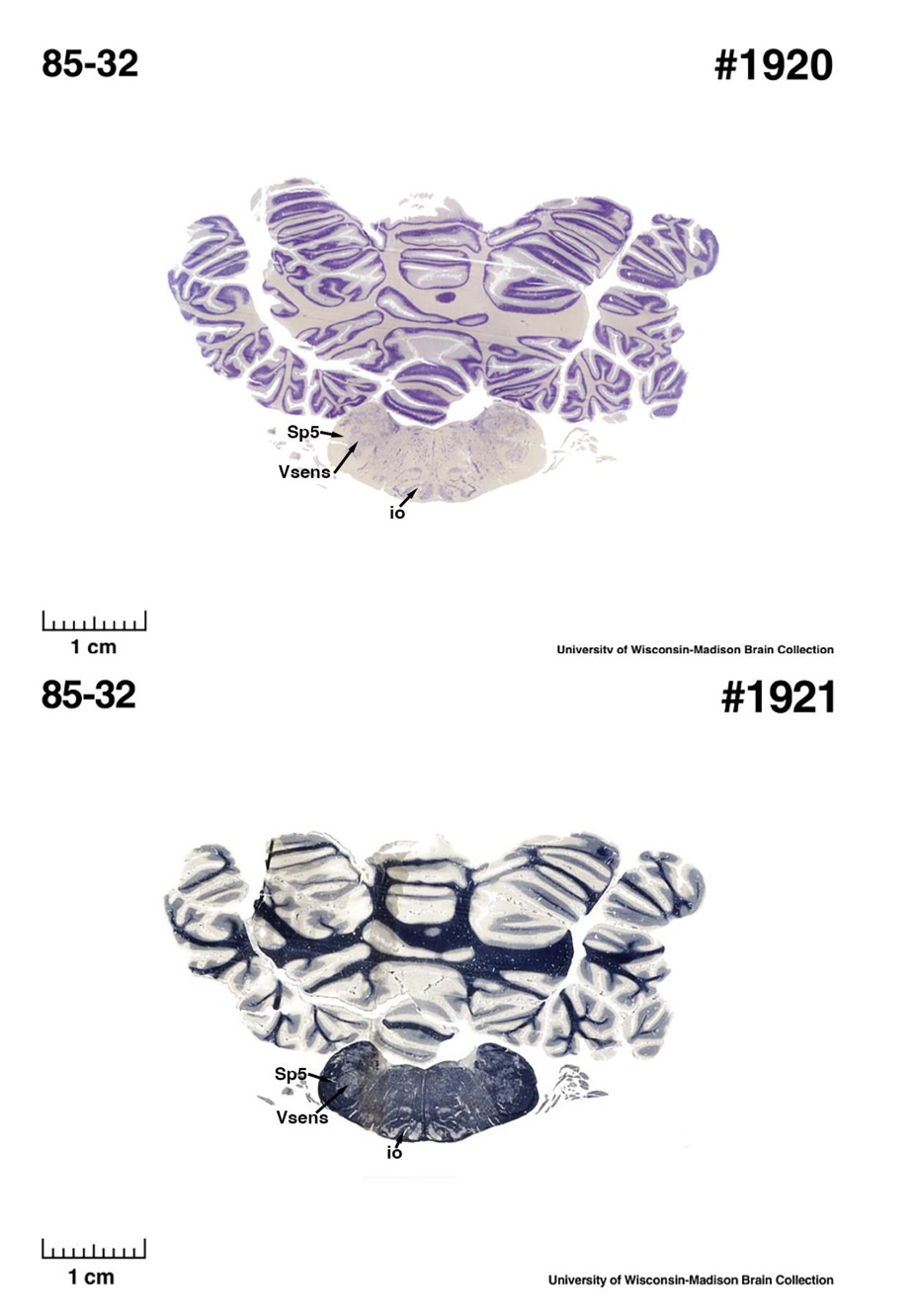

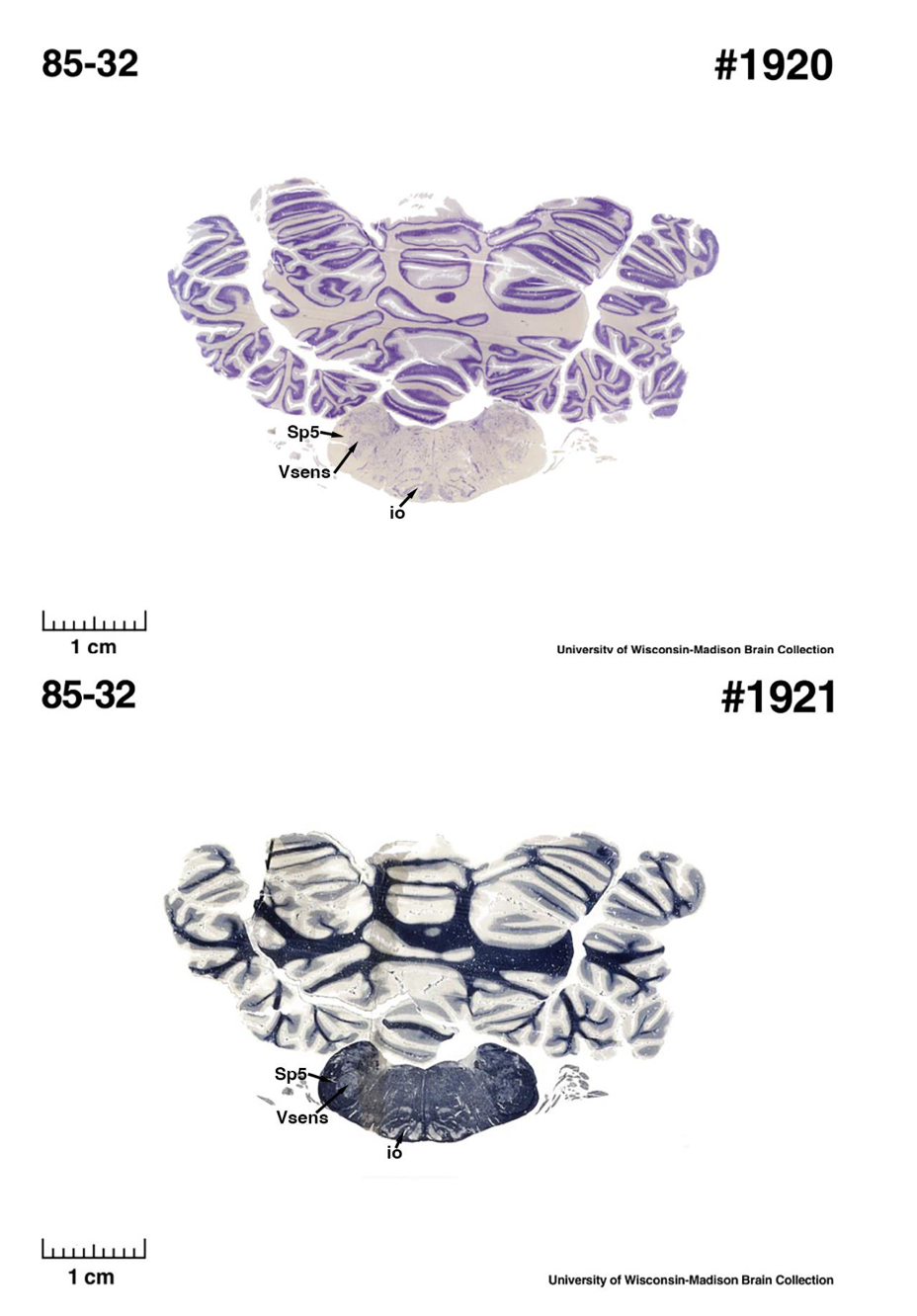

(E) West Indian manatee (Trichechus manatus)

The sirens are the closest extant relatives of the elephants in the Afrotheria. Below I append images of cresyl violet (top) and myelin (bottom) stained coronal sections (taken from the University of Wisconsin-Madison Brain Collection, https://brainmuseum.org, and while quite low in magnification they do reveal the structures under debate) through the brainstem with the IO, Vsens and Sp5 labelled as per standard mammalian anatomy. Here we see the serration of the IO (as defined by the authors). Vsens is located laterally and skirted by the Sp5. This is in agreement with the authors, as they propose that ONLY the elephants show the variations they report.

Review image 5.

These comparisons and the structural identification, with which the authors agree as they only distinguish the elephants from the other Afrotheria, demonstrate that the appearance of the IO can be quite variable across mammalian species, including those with a close phylogenetic affinity to the elephants. Not all mammal species possess a "serrated" appearance of the IO. Thus, it is more than just theoretically possible that the IO of the elephant appears as described prior to this study.

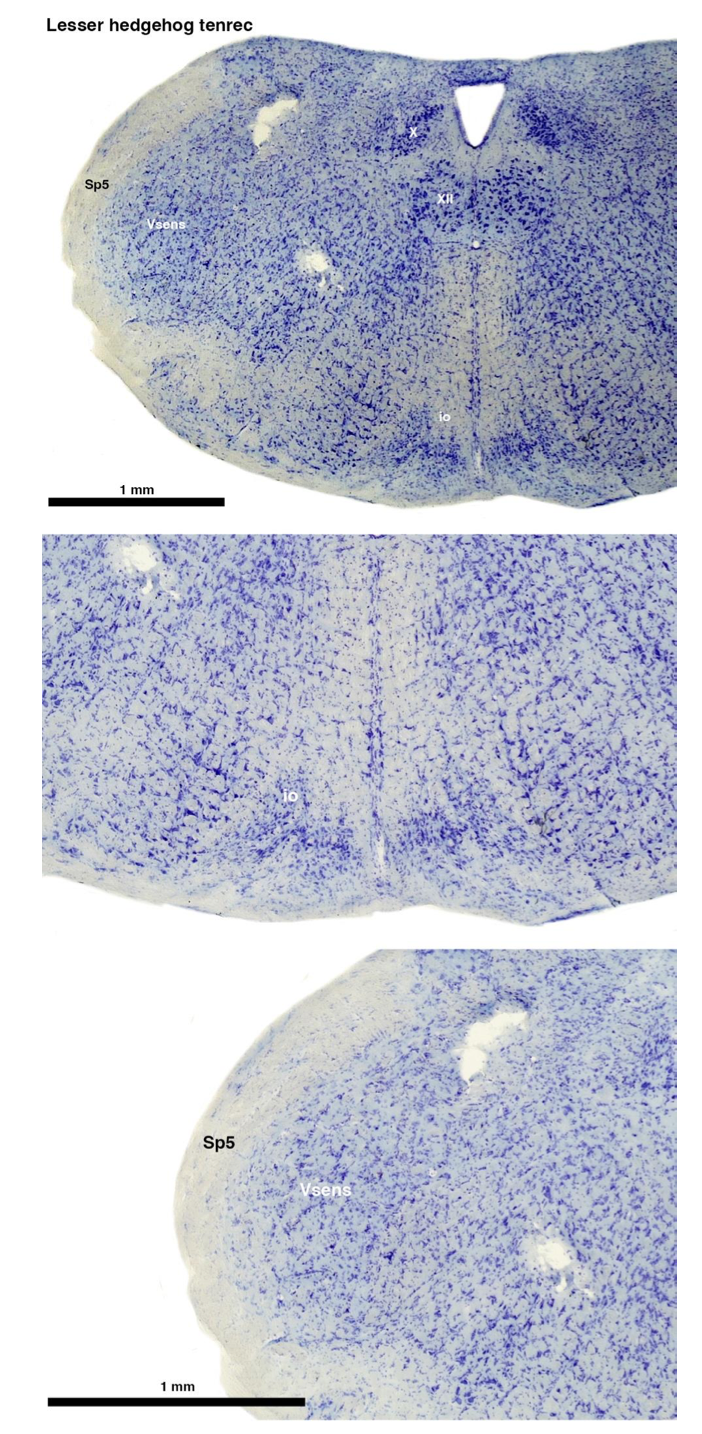

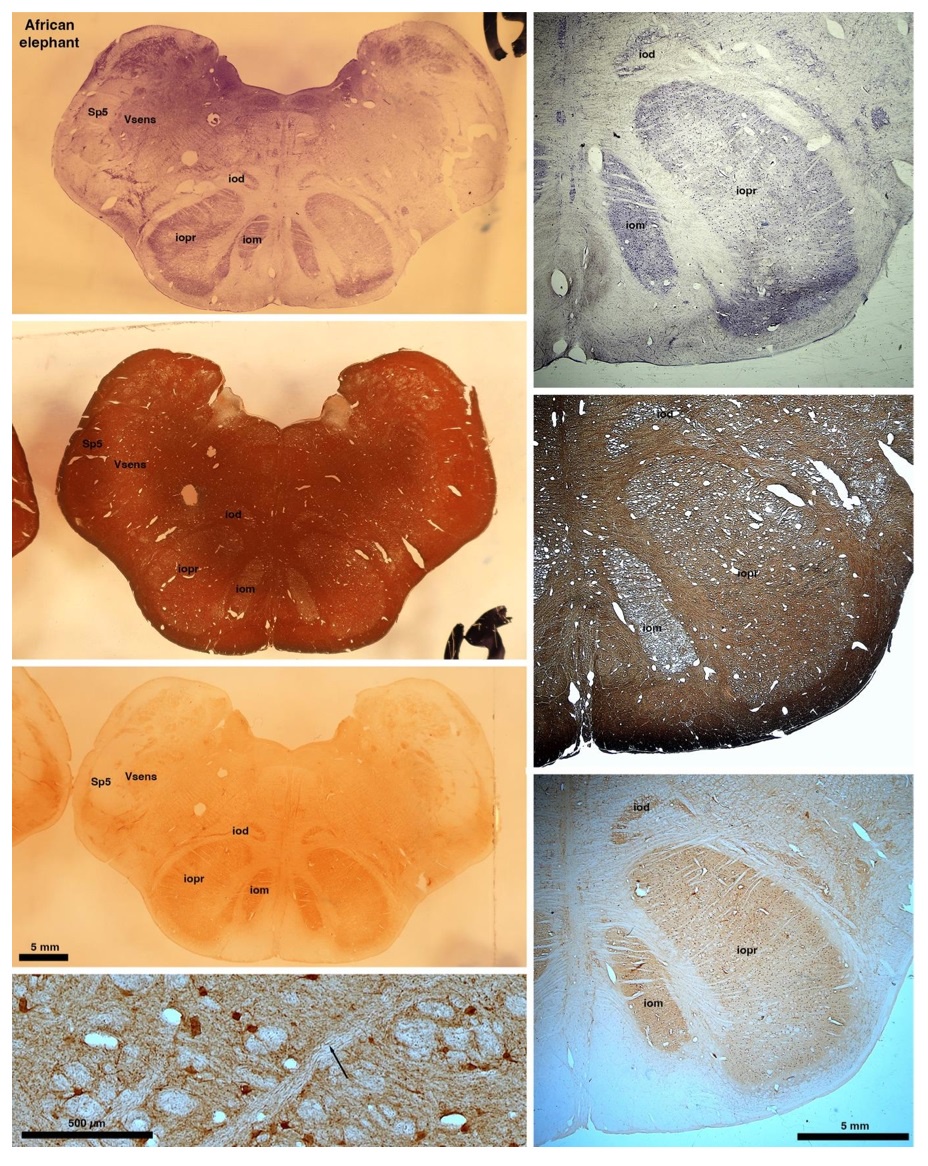

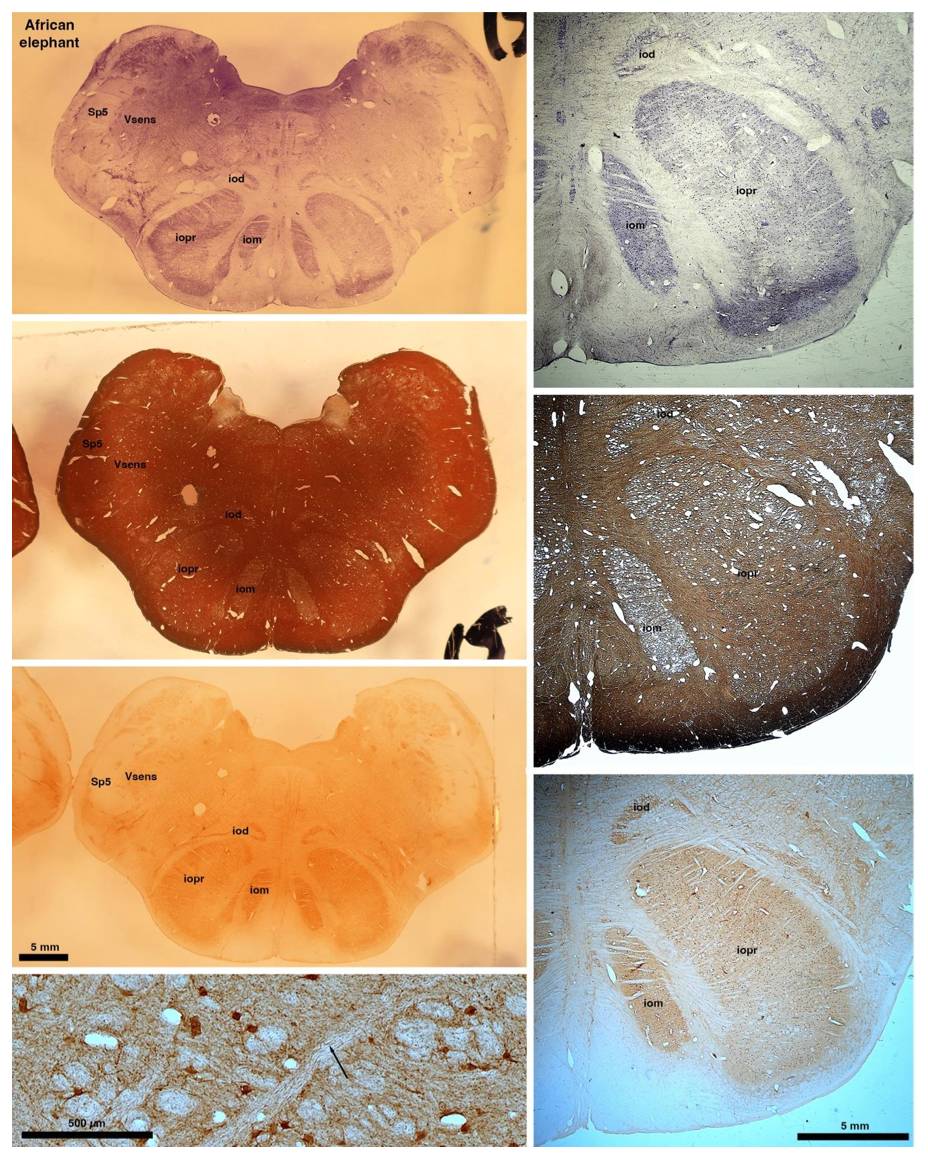

So what about elephants? Below I append a series of images from coronal sections through the African elephant brainstem stained for Nissl, myelin, and immunostained for calretinin. These sections are labelled according to standard mammalian nomenclature. In these complete sections of the elephant brainstem, we do not see a serrated appearance of the IOM (as described previously and in the current study by the authors). Rather the principal nucleus of the IOM appears to be bulbous in nature. In the current study, no image of myelin staining in the IOM/VsensR is provided by the authors. However, in the images I provide, we do see the reported myelin stripes in all stains - agreement between the authors and reviewer on this point. The higher magnification image to the bottom left of the plate shows one of the IOM/VsensR myelin stripes immunostained for calretinin, and within the myelin stripes axons immunopositive for calretinin are seen (labelled with an arrow). The climbing fibres of the elephant cerebellar cortex are similarly calretinin immunopositive (10.1159/000345565). In contrast, although not shown at high magnification, the fibres forming the Sp5 in the elephant (in the Maseko description, unnamed in the description of the authors) show no immunoreactivity to calretinin.

Review image 6.

Peripherin Immunostaining

In their revised manuscript the authors present immunostaining of peripherin in the elephant brainstem. This is an important addition (although it does replace the only staining of myelin provided by the authors which is unusual as the word myelin is in the title of the paper) as peripherin is known to specifically label peripheral nerves. In addition, as pointed out by the authors, peripherin also immunostains climbing fibres (Errante et al., 1998). The understanding of this staining is important in determining the identification of the IO and Vsens in the elephant, although it is not ideal for this task as there is some ambiguity. Errante and colleagues (1998; Fig. 1) show that climbing fibres are peripherin-immunopositive in the rat. But what the authors do not evaluate is the extensive peripherin staining in the rat Sp5 in the same paper (Errante et al, 1998, Fig. 2). The image provided by the authors of their peripherin immunostaining (their new Figure 2) shows what I would call the Sp5 of the elephant to be strongly peripherin immunoreactive, just like the rat shown in Errant et al (1998), and moreover in the precise position of the rat Sp5! This makes sense as this is where the axons subserving the "extraordinary" tactile sensitivity of the elephant trunk would be found (in the standard model of mammalian brainstem anatomy). Interestingly, the peripherin immunostaining in the elephant is clearly lamellated...this coincides precisely with the description of the trigeminal sensory nuclei in the elephant by Maskeo et al (2013) as pointed out by the authors in their rebuttal. Errante et al (1998) also point out peripherin immunostaining in the inferior olive, but according to the authors this is only "weakly present" in the elephant IOM/VsensR. This latter point is crucial. Surely if the elephant has an extraordinary sensory innervation from the trunk, with 400,000 axons entering the brain, the VsensR/IOM should be highly peripherin-immunopositive, including the myelinated axon bundles?! In this sense, the authors argue against their own interpretation - either the elephant trunk is not a highly sensitive tactile organ, or the VsensR is not the trigeminal nuclei it is supposed to be.

Summary:

(1) Comparative data of species closely related to elephants (Afrotherians) demonstrates that not all mammals exhibit the "serrated" appearance of the principal nucleus of the inferior olive.

(2) The location of the IO and Vsens as reported in the current study (IOR and VsensR) would require a significant, and unprecedented, rearrangement of the brainstem in the elephants independently. I argue that the underlying molecular and genetic changes required to achieve this would be so extreme that it would lead to lethal phenotypes. Arguing that the "switcheroo" of the IO and Vsens does occur in the elephant (and no other mammals) and thus doesn't lead to lethal phenotypes is a circular argument that cannot be substantiated.

(3) Myelin stripes in the subnuclei of the inferior olivary nuclear complex are seen across all related mammals as shown above. Thus, the observation made in the elephant by the authors in what they call the VsensR, is similar to that seen in the IO of related mammals, especially when the IO takes on a more bulbous appearance. These myelin stripes are the origin of the olivocerebellar pathway and are indeed calretinin immunopositive in the elephant as I show.

(4) What the authors see aligns perfectly with what has been described previously, the only difference being the names that nuclear complexes are being called. But identifying these nuclei is important, as any functional sequelae, as extensively discussed by the authors, is entirely dependent upon accurately identifying these nuclei.

(4) The peripherin immunostaining scores an own goal - if peripherin is marking peripheral nerves (as the authors and I believe it is), then why is the VsensR/IOM only "weakly positive" for this stain? This either means that the "extraordinary" tactile sensitivity of the elephant trunk is non-existent, or that the authors have misinterpreted this staining. That there is extensive staining in the fibre pathway dorsal and lateral to the IOR (which I call the spinal trigeminal tract), supports the idea that the authors have misinterpreted their peripherin immunostaining.

(5) Evolutionary expediency. The authors argue that what they report is an expedient way in which to modify the organisation of the brainstem in the elephant to accommodate the "extraordinary" tactile sensitivity. I disagree. As pointed out in my first review, the elephant cerebellum is very large and comprised of huge numbers of morphologically complex neurons. The inferior olivary nuclei in all mammals studied in detail to date, give rise to the climbing fibres that terminate on the Purkinje cells of the cerebellar cortex. It is more parsimonious to argue that, in alignment with the expansion of the elephant cerebellum (for motor control of the trunk), the inferior olivary nuclei (specifically the principal nucleus) have had additional neurons added to accommodate this cerebellar expansion. Such an addition of neurons to the principal nucleus of the inferior olive could readily lead to the loss of the serrated appearance of the principal nucleus of the inferior olive and would require far less modifications in the developmental genetic program that forms these nuclei. This type of quantitative change appears to be the primary way in which structures are altered in the mammalian brainstem.