- Apr 2017

-

www.gutenberg.org www.gutenberg.org

-

He assured the company that it was a fact, handed down from his ancestor, the historian, that the Kaatskill mountains had always been haunted by strange beings. That it was affirmed that the great Hendrick Hudson, the first discoverer of the river and country, kept a kind of vigil there every twenty years, with his crew of the Half-moon; being permitted in this way to revisit the scenes of his enterprise, and keep a guardian eye upon the river and the great city called by his name. That his father had once seen them in their old Dutch dresses playing at ninepins in the hollow of the mountain; and that he himself had heard, one summer afternoon, the sound of their balls, like distant peals of thunder.

This solidifies the fact that these ghosts are “real” (at least in the world of the narrative) since they have been noted by other people then just Rip, and have similar stories of interactions/observations between the Dutch ghosts and members of the town.

-

He doubted his own identity, and whether he was himself or another man.

This moment provides an example of an existentialist dilemma in the form of dissociative dread toward his understanding of self. Rip’s confusion is so strong that it causes him to doubt the nature of his own being.

-

stared at him with such a fixed statue-like gaze, and such strange uncouth, lack-lustre countenances, that his heart turned within him, and his knees smote together.

This is a moment defining real fear towards his current predicament.

-

On nearer approach, he was still more surprised at the singularity of the stranger’s appearance. He was a short, square-built old fellow, with thick bushy hair, and a grizzled beard. His dress was of the antique Dutch fashion—a cloth jerkin strapped round the waist—several pairs of breeches, the outer one of ample volume, decorated with rows of buttons down the sides, and bunches at the knees. He bore on his shoulders a stout keg, that seemed full of liquor, and made signs for Rip to approach and assist him with the load. Though rather shy and distrustful of this new acquaintance, Rip complied with his usual alacrity;

These Dutch ghosts are part of the history of the area but are also tangible forces that drive the plot. Rip can physically interact with these ghosts as if they were normal people, the only thing that proves odd is that they do not speak. Regardless, they are ghosts that are more like echoes of a time past that can be encountered, rather than being antagonistic like the ambiguous forces that Poe presents in his works.

-

As he was about to descend, he heard a voice from a distance hallooing: “Rip Van Winkle! Rip Van Winkle!” He looked around, but could see nothing but a crow winging its solitary flight across the mountain. He thought his fancy must have deceived him, and turned again to descend, when he heard the same cry ring through the still evening air, “Rip Van Winkle! Rip Van Winkle!”—at the same time Wolf bristled up his back, and giving a low growl, skulked to his master’s side, looking fearfully down into the glen. Rip now felt a vague apprehension stealing over him; he looked anxiously in the same direction, and perceived a strange figure slowly toiling up the rocks, and bending under the weight of something he carried on his back. He was surprised to see any human being in this lonely and unfrequented place, but supposing it to be some one of the neighborhood in need of his assistance, he hastened down to yield it.

This build up provides a sense of apprehension, with Wolf detecting some sort of danger and the odd way that Rip’s name was being called through echo. This does not stop him from proceeding onward to make his chance meeting with the company of Dutch ghosts.

-

“Oh! that flagon! that wicked flagon!”

A loose connection to Poe within the realm of alcahol playing a part in altered mind states.

-

His mind now misgave him; he began to doubt whether both he and the world around him were not bewitched.

The assumption that one has come under a spell or some other form of witchcraft would be a real fear for people of the time. Many believed the early superstitions, and while they acted as explanations for things they could not explain, they acted as warnings and preventive measures for certain behavior. Stories of ghosts and witches could be used to keep people away from dangerous territories, or provide lessons about needing to be more attentive to the possible dangers found outside of the safety of civilization. Irvings other works (like Legend of Sleepy Hallow) highlight the impact that fear can has on the mind.

-

The moment Wolf entered the house, his crest fell, his tail drooped to the ground, or curled between his legs, he sneaked about with a gallows air, casting many a sidelong glance at Dame Van Winkle, and at the least flourish of a broomstick or ladle, he would fly to the door with yelping precipitation.

This is a light bit of foreshadowing, noting that the dog has a sense for danger. It comes up again when Rip is about to encounter the Dutch ghosts.

-

The great error in Rip’s composition was an insuperable aversion to all kinds of profitable labor. It could not be for want of assiduity or perseverance

Rip as a character is surprisingly similar to Irving in his mannerisms. Though it is not as widely known, Irving had a similar aversion to labor due to a massive amount of anxiety brought on by the failure of his brother’s businesses after the Revolution. The fear of the state of the new nation was noticeable in how drastically the economy was shifting, which was one of the deciding factors that pushed Irving into writing and publishing. It was a way to secure some financial stability and support for his family’s livelihood while also avoiding ventures that could, at any moment due to the young nation’s “growing pains”, could fail and lead to ruin (Kopec).

-

ghosts, witches, and Indians.

Most of the early American folklore has been lost to time, since many of these stories were told mainly by word of mouth alone. Irving was one of the first to solidify local folklore in his works, practically starting the genre of “campfire narratives” in literature. His short piece of horror fiction, Legend of Sleepy Hallow, is what pioneered the American Gothic form of literature, which would be later built upon by writers like Poe.

-

RIP VAN WINKLE.

The annotations below are focused on the themes and language of American gothic horror and the connection to another text located here.

Associated Sources in MLA Style:

Badenhausen, Richard. "Fear and Trembling in Literature of the Fantastic: Edgar Allan Poe's 'The Black Cat'." Studies in Short Fiction, vol. 29, no. 4, 1992, pp. 487-498. EBSCOhost.

Bann, Jennifer. "Ghostly Hands and Ghostly Agency: The Changing Figure of the Nineteenth-Century Specter." Victorian Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Social, Political, and Cultural Studies, vol. 51, no. 4, 2009, pp. 663-686. EBSCOhost.

Kopec, Andrew. "Irving, Ruin, and Risk." Early American Literature, vol. 48, no. 3, Nov. 2013, pp. 709-735. EBSCOhost.

Norton, Mary Berth. "Witchcraft in the Anglo-American Colonies." OAH Magazine of History, vol. 17, no. 4, July 2003, pp. 5-9. EBSCOhost.

-

-

www.gutenberg.org www.gutenberg.org

-

It was now the representation of an object that I shudder to name—and for this, above all, I loathed, and dreaded, and would have rid myself of the monster had I dared—it was now, I say, the image of a hideous—of a ghastly thing—of the GALLOWS!—oh, mournful and terrible engine of Horror and of Crime—of Agony and of Death!

Here is a distinct fear of the gallows, something the narrator has told us he is condemned to for his crime at the beginning of his tale. The fear outlined in this sentence represents the narrator’s true fear, the fear of facing what he has done. The gallows are an object for delivering punishment through the death of the criminal. The narrator constantly faced fear, guilt, and anger but fails to address their effects throughout the story. He instead chooses to run away from these emotions by burying them in alcohol or just remove them from his life with violence. This is the only moment that causes the narrator to seize up and deliver short hyphenated statements, which to a reader would sound quick and manic. This fear is an existential fear of closure and finality, now that the narrator has own death it shows through the text a moment of vulnerability (Badenhausen 492-493).

-

But may God shield and deliver me from the fangs of the Arch-Fiend! No sooner had the reverberation of my blows sunk into silence, than I was answered by a voice from within the tomb!—by a cry, at first muffled and broken, like the sobbing of a child, and then quickly swelling into one long, loud, and continuous scream, utterly anomalous and inhuman—a howl—a wailing shriek, half of horror and half of triumph, such as might have arisen only out of hell, conjointly from the throats of the dammed in their agony and of the demons that exult in the damnation.

Here the replacement cat (and possible paranormal force) acts upon the plot by revealing the narrators misdeeds. Like Irving’s Dutch ghosts, this mysterious cat is integral to the story for without their influence the main characters would be unaffected. Again, this cat provides another confusing instance of possible paranormal power by somehow ending up inside the wall. The narrator hated the creature so much, how could he have missed it as he bricked up his wife’s corpse? It either had managed to avoid detection to hide itself within the wall, or had some greater power that allowed it to appear there as it had in the tavern.

-

I withdrew my arm from her grasp and buried the axe in her brain. She fell dead upon the spot, without a groan.

This is the point of no return, where the narrator goes from mere killer of beast to full villain with manslaughter. He is unmoved by killing the thing that prevented him from taking out his anger again, she had interrupted his control and for that she died.

-

Pluto had not a white hair upon any portion of his body; but this cat had a large, although indefinite splotch of white, covering nearly the whole region of the breast. Upon my touching him, he immediately arose, purred loudly, rubbed against my hand, and appeared delighted with my notice. This, then, was the very creature of which I was in search. I at once offered to purchase it of the landlord; but this person made no claim to it—knew nothing of it—had never seen it before.

Just like the mark on the wall, this is another stange occuance that could be related to the paranormal. This cat appears out of nowhere and specifically targets the narrator. It could be seen as an antagonistic force, a manifestation meant to spell the narrator’s downfall. Again, Pluto’s name is referenced, calling back to the idea of death and relating it to this new cat. Its lack of an eye is an intentional narrative decision by Poe, but in the world inside the text is strangely coincidental to be near identical to Pluto, almost unsettling so. What is interesting about this cat is that the white tuft of fur it sports “develops” the image of the stockade. Either an outside force is at work on the cat’s fur, or the cat itself is a doppelganger (a supernatural creature that morphs its own body to match another’s appearance) of sorts.

-

I approached and saw, as if graven in bas relief upon the white surface, the figure of a gigantic cat. The impression was given with an accuracy truly marvellous. There was a rope about the animal’s neck.

This odd occurrence might be attributed to something paranormal. As the narrator later explains, it is physically possible for flesh remains to leave burn impressions on surfaces. However, the corpse of the cat would have to have been resting against the wall for that impression to develop, and the chances of that happening to produce such a haunting representation is highly improbable. Perhaps there was some sort of other force at work and it made possible the author’s explanation or something else entirely. Whatever the case, it remains unknown, but a reader can confirm that within the world of the narrative because it is a tangible remnant viewed by multiple people and not just the narrator.

-

One night as I sat, half stupified, in a den of more than infamy

The narrator never seeks to remedy his situation, only to run from it or drink it away.

-

I experienced a sentiment half of horror, half of remorse, for the crime of which I had been guilty

These are the common themes Poe tends to play on throughout his body of work, which are tied to very personal and emotional moments. A healthy human mind is capable of a vast array of different feelings, each meant to inform thought via bodily sensations and responses. If the narrator can comprehend the emotions, but does not associate them to his crime, is it an effect of alcohol? Could it be something darker, something stemming from a broken mind?

-

spirit of PERVERSENESS

This is not a "physical" sprit like those in Irving's works. In this case, "spirit" embodies the “feeling” or the “quality of” what it is referencing. The spirit of perverseness would be something of a compulsion, something internal that forces negative action and/or thought.

-

Pluto

This is a bit of plain faced foreshadowing. Pluto is the Roman equivalent of Hades, the god of death and overseer for the underworld. The name calls upon the imagery of darkness and death, which no doubt plays into the narrative throughout.

-

In speaking of his intelligence, my wife, who at heart was not a little tinctured with superstition, made frequent allusion to the ancient popular notion, which regarded all black cats as witches in disguise.

The concept of the witch played a large role in the development of colonial America, and the superstitions surrounding witchcraft are usually connected to larger outside forces that were difficult to explain or comprehend. Disease, injury, misfortune, and other tragic events that would occur were often blamed on fellow townsfolk that had preexisting issues or disagreements with others (Norton 5-6). Due to the empiricist model of thought, perception defined reality, so all that was required to prove someone was capable of witchcraft was to “experience” the effects. If someone said they saw a person turn into a cat, it was taken as proper testimony to the event.

It is interesting that the wife holds this belief, yet the narrator downplays it. Perhaps that is a veiled critique of these old superstitions.

-

But my disease grew upon me—for what disease is like Alcohol!

Poe was a known alcholic, so it is interesting how he comments on it a being a "disease" with this narrator character. Perhaps there is more self-inserted introspection involved then his usual themes of guilt, sadness, and loss noteable in his other works.

-

THE BLACK CAT.

The annotations below are focused on the themes and language of American gothic horror and the connection to another text located here.

Associated Sources in MLA Style:

Badenhausen, Richard. "Fear and Trembling in Literature of the Fantastic: Edgar Allan Poe's 'The Black Cat'." Studies in Short Fiction, vol. 29, no. 4, 1992, pp. 487-498. EBSCOhost.

Bann, Jennifer. "Ghostly Hands and Ghostly Agency: The Changing Figure of the Nineteenth-Century Specter." Victorian Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Social, Political, and Cultural Studies, vol. 51, no. 4, 2009, pp. 663-686. EBSCOhost.

Kopec, Andrew. "Irving, Ruin, and Risk." Early American Literature, vol. 48, no. 3, Nov. 2013, pp. 709-735. EBSCOhost.

Norton, Mary Berth. "Witchcraft in the Anglo-American Colonies." OAH Magazine of History, vol. 17, no. 4, July 2003, pp. 5-9. EBSCOhost.

-

-

-

Put this in the crown of your hats, gentlemen! A fool of either sex is the hardest animal to drive that ever required a bit. Better one who jumps a fence now and then, than your sulky, stupid donkey, whose rhinoceros back feels neither pat or goad.

Rough paraphrase: “Get this through your heads! An idiot, male or female, is the hardest thing to convince to change their mind. It is better to have someone that completely surprises you now and again with his or her ideas, instead of someone who remains so stubbornly close-minded they cannot feel good or bad about it.”

This is the closing “emotional punch” required to grab a reader, perhaps even agitate them. as long as it draws attention, it can be an effective tactic to illustrate the point the author wishes to make. With an approach that is both emotional and even mildly condescending, this is the form of editorial form Fern is talking about women needing to apply themselves to throughout the body of her own editorial.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

- Dec 2016

-

ignisart.com ignisart.com

-

THE SPECKLED BAND

WORK CITED:

Gelly, Christophe. "Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes Stories: Crime and Mystery from the Text to the Illustrations.” Cahiers victoriens et édouardiens. Volume 73: Issue No. 1 (2011), 107-129. JSTOR.

Hodgson, John. “The Recoil of "The Speckled Band": Detective Story and Detective Discourse.” Poetics Today. Volume 12: Issue No. 2 (1992), 309-324. JSTOR.

Metress, Christopher. “Thinking the Unthinkable: Reopening Conan Doyle's "Cardboard Box." The Midwest Quarterly. Volume 42: Issue No. 2 (2001), 183. JSTOR.

Pratt-Smith, Stella. “The other serpents: deviance and contagion in "The Speckled Band." Victorian Newsletter. Volume 113 (2008), 54. JSTOR.

-

The little which I had yet to learn of the case was told me by Sherlock Holmes as we travelled back next day.

The third and final part of the Holmes formula. Holmes returns back to Baker Street with Watson, where he tells Watson (as well as the reader) how he came to the conclusions he did.

-

“I had come to these conclusions before ever I had entered his room. An inspection of his chair showed me that he had been in the habit of standing on it, which of course would be necessary in order that he should reach the ventilator. The sight of the safe, the saucer of milk, and the loop of whipcord were enough to finally dispel any doubts which may have remained. The metallic clang heard by Miss Stoner was obviously caused by her stepfather hastily closing the door of his safe upon its terrible occupant. Having once made up my mind, you know the steps which I took in order to put the matter to the proof. I heard the creature hiss as I have no doubt that you did also, and I instantly lit the light and attacked it.”

This explanation of how Holmes came to his conclusions are fairly flawed. In conjunction with the issues with the snake, Hodgson writes, "The appeal of Sherlock Holmes, after all, comes from his method and his skillful application of it. Holmes is the master reasoner, diagnostician, interpreter: he not only sees (Watson can do as much), he makes sense of what he sees, thanks to his vast store of useful, if often esoteric, knowledge and his highly developed powers of inference. But in "The Speckled Band" Holmes makes nonsense of what he sees; here, to a degree unmatched elsewhere in the canon, his method is not merely shaky, but overtly and devastatingly flawed."

-

“It is a swamp adder!” cried Holmes; “the deadliest snake in India. He has died within ten seconds of being bitten. Violence does, in truth, recoil upon the violent, and the schemer falls into the pit which he digs for another. Let us thrust this creature back into its den, and we can then remove Miss Stoner to some place of shelter and let the county police know what has happened.”

This is one of the plot holes in "The Speckled Band". Hodgson writes in his article, "Snakes don't have ears...can't survive in an airtight safe. There's no such thing as an Indian swamp adder. No snake poison could have killed a huge man like Grimesby Roylott instantly."

-

Subtle enough and horrible enough. When a doctor does go wrong he is the first of criminals. He has nerve and he has knowledge. Palmer and Pritchard were among the heads of their profession. This man strikes even deeper, but I think, Watson, that we shall be able to strike deeper still.

Both men were doctors who were convicted of murder by poison. Dr. William Palmer was executed on the 6th of August 1824 in Stafford, Staffordshire. Dr. Edward Pritchard was executed on the 28th of July, 1865 in Glasgow, Scotland.

-

“It is a nice household,” he murmured. “That is the baboon.” I had forgotten the strange pets which the doctor affected. There was a cheetah, too; perhaps we might find it upon our shoulders at any moment.

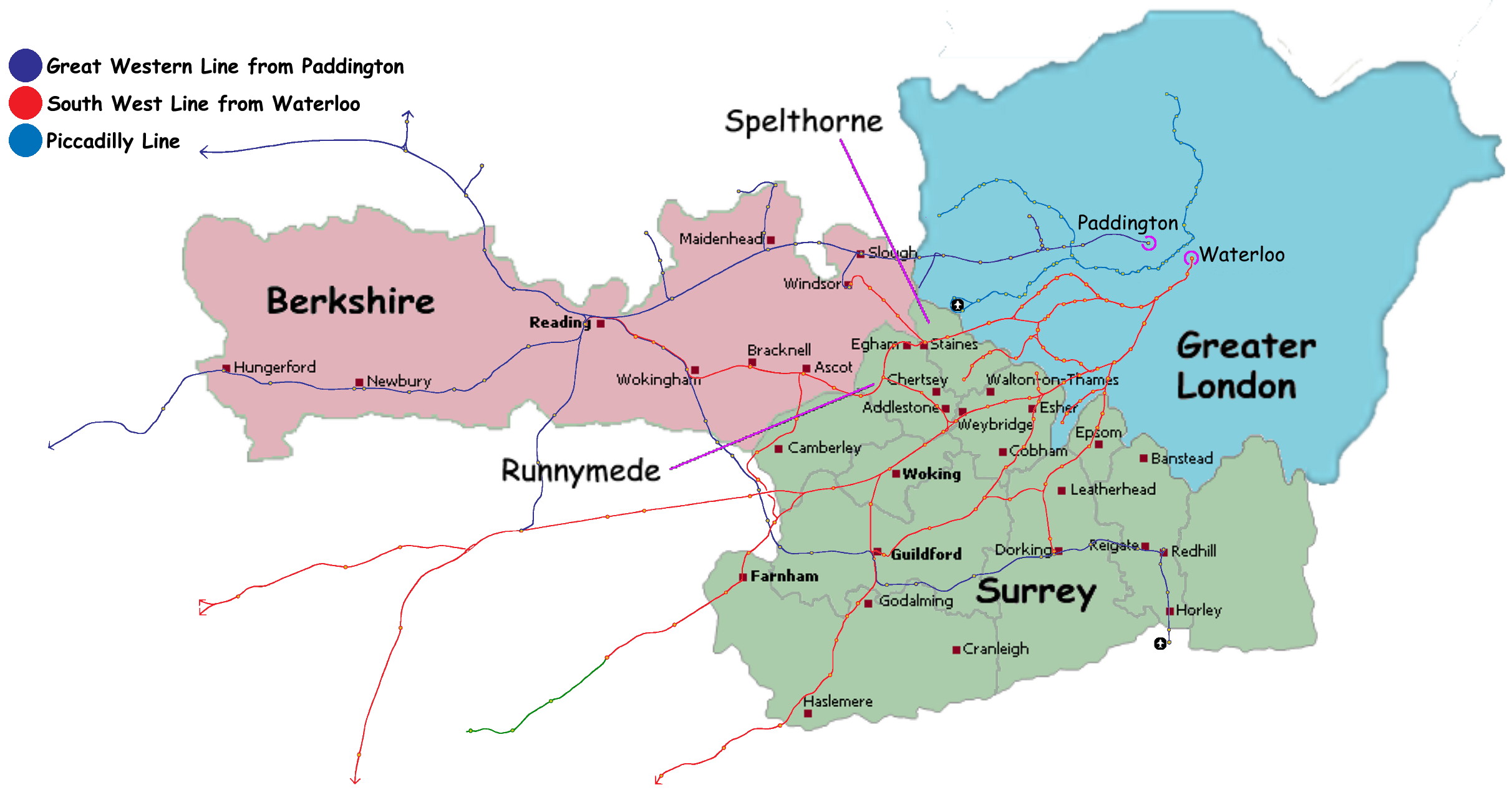

The various exotic pets that the doctor has around the house serve to make the manner feel alien to the rest of the town, bringing the foreign feeling of imperialism from India to Surrey. It makes the grounds seem dangerous and inaccessible, distancing Helen and her father from everyone else.

-

unrepaired breaches [271] gaped

According to the OED, breaches means " A disrupted place, gap, or fissure, caused by the separation of continuous parts; a break.' Gaped means "Of material objects, wounds, etc.: To open as a mouth; to split, crack, part asunder." With the manor grounds in such disrepair, it was easy for Holmes and Watson to gain entrance.

-

“You speak of danger. You have evidently seen more in these rooms than was visible to me.” “No, but I fancy that I may have deduced a little more. I imagine that you saw all that I did.” “I saw nothing remarkable save the bell-rope, and what purpose that could answer I confess is more than I can imagine.” “You saw the ventilator, too?” “Yes, but I do not think that it is such a very unusual thing to have a small opening between two rooms. It was so small that a rat could hardly pass through.”

This part is showcasing Holmes' remarkable ability of deduction, reasoning, and inference. His assistant Watson, who is also an extremely educated and smart man, did not notice many things that Holmes did during their walkthrough of the manor. This is a hallmark of detection fiction, showing that the main character is highly intelligent, smarter than the normal person.

-

scruples

According to the OED, scruples means, "A thought or circumstance that troubles the mind or conscience; a doubt, uncertainty or hesitation in regard to right and wrong, duty, propriety, etc.; esp. one which is regarded as over-refined or over-nice, or which causes a person to hesitate where others would be bolder to act." Sherlock is worried by the amount of danger that may face Watson by joining him in the manor.

-

“I believe, Mr. Holmes, that you have already made up your mind,” said Miss Stoner, laying her hand upon my companion’s sleeve. “Perhaps I have.” “Then, for pity’s sake, tell me what was the cause of my sister’s death.” “I should prefer to have clearer proofs before I speak.” “You can at least tell me whether my own thought is correct, and if she died from some sudden fright.” “No, I do not think so. I think that there was probably some more tangible cause. And now, Miss Stoner, we must leave you, for if Dr. Roylott returned and saw us our journey would be in vain. Good-bye, and be brave, for if you will do what I have told you you may rest assured that we shall soon drive away the dangers that threaten you.”

Conan Doyle has peaked the reader's interest at this point in the story. He has laid out all of the clues and they seem to not add up to much. However, Holmes has formed a hypothesis and believes he knows the answers. In Metress' article in the Midwest Quarterly, he writes, "Why does Helen's room contain a vent that connects, not with the outside and fresh air, but with another room? Why does the room have a bell-rope that is unconnected to a bell? Why does the room contain a bed that is bolted to the floor? What can all this mean? Although Sherlock Holmes assures Helen Stoner in the first section of the tale that "There is no mystery," now, in the second section of the tale, there is nothing but mystery. Thus, what is "inconceivable" at the beginning of this and all other tales--"that all united should fail to enlighten"--is not only conceivable but highly probable."

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.gutenberg.org www.gutenberg.org

-

when I am glowing with the enthusiasm of success, there will be none to participate my joy; if I am assailed by disappointment, no one will endeavour to sustain me in dejection. I shall commit my thoughts to paper, it is true; but that is a poor medium for the communication of feeling.

The sentiments expressed by Walton mirror those proposed by Anthony F. Badalamenti in his article, "Why did Mary Shelley Write Frankenstein?" (http://search.proquest.com/docview/756918789?pq-origsite=summon)

In the article, Badalamenti cites Shelley's estranged relationship with her parents as a possible driving force for the novel's creation. Shelley's birth-mother died soon following her delivery. Her father later remarried to Mary Jane Clairmont who, "showed little regard for young Mary’s gifts or for the breadth of her interests" Furthermore, Badalamenti says, "Mary saw her stepmother as distancing her father from her and as coming between them." This distance ultimately left a thin hope for connection through the craft that Shelley and her biological parents shared: writing. In Badalamenti's words, "Mary Shelley was deeply attached to her parents’ works, the one deepening her tie to her father and the other among her few means of knowing her natural mother."

Considering Shelley's experiences, Walton's thoughts could demonstrate how, despite trying to close the gap between her creators through common interests, her parents' emotional and physical absence made it impossible to reach them. In that sense, Walton's angst would be an expression of Shelley's as well: lamenting the inability to share success or grief with another.

Badalamenti, A. F. (2006). Why did mary shelley write frankenstein? Journal of Religion and Health, 45(3), 419-439. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10943-006-9030-0

-

Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus

Further Reading:

"Why did Mary Shelley Write Frankenstein?" - Anthony F. Badalamenti (http://search.proquest.com/docview/756918789?pq-origsite=summon)

Badalamenti, A. F. (2006). Why did mary shelley write frankenstein? Journal of Religion and Health, 45(3), 419-439. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10943-006-9030-0

"Strangers and Orphans: Knowledge and mutuality in Mary Shelley's Frankenstein" - Claudia Rozas Gomez (http://web.b.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=93864b1c-c2de-488e-9f82-3e3ebeb47ee9%40sessionmgr107&vid=1&hid=125)

Gómez, Claudia Rozas. Strangers and orphans: Knowledge and mutuality in Mary Shelley's Frankenstein. Educational philosophy and theory 45.4 2013: 360-370. Blackwell Publishing. 09 Dec 2016.

"Frankenstein: A Child's Tale." - Marshall Brown (http://web.a.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail/detail?sid=ad64c71d-93fd-40c6-b899-57e627ea0a05%40sessionmgr4009&vid=0&hid=4112&bdata=JkF1dGhUeXBlPWlwLHVpZCZzY29wZT1zaXRl#AN=12672272&db=aph)

Brown, Marshall. "Frankenstein: A Child's Tale." Novel: A Forum On Fiction 36.2 (2003): 145-175. Academic Search Premier. Web. 9 Dec. 2016.

"Can Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein be read as an early research ethics text?" - Hugh Davies (http://mh.bmj.com/content/30/1/32.full)

Davies, Hugh. "Can Mary Shelley's Frankenstein be Read as an Early Research Ethics Text?" Medical Humanities, vol. 30, no. 1, 2004., pp. 32-35doi:10.1136/jmh.2003.000153.

-

devoted my nights to the study of mathematics, the theory of medicine, and those branches of physical science from which a naval adventurer might derive the greatest practical advantage.

Hugh Davies cited this passage in his article, "Can Mary Shelley's Frankenstein be read as an early research ethics text?" (http://mh.bmj.com/content/30/1/32.full)

In the article, Dvies uses this passage as a counter-argument against assertions that Frankenstein is solely a cautionary tale. In Walton's words, he provides an example of how scientific research can be intended for positive outcomes. Davies's intention with this claim is to demonstrate that Shelley viewed scientific discovery is from a dual perspective and did not set out to solely condemn or praise to pursuit of knowledge, but to emphasize the need for moderation.

Davies, Hugh. "Can Mary Shelley's Frankenstein be Read as an Early Research Ethics Text?" Medical Humanities, vol. 30, no. 1, 2004., pp. 32-35doi:10.1136/jmh.2003.000153.

-

My father was enraptured on finding me freed from the vexations of a criminal charge, that I was again allowed to breathe the fresh atmosphere and permitted to return to my native country.

Criminal court cases are held very similar to that of the United States criminal court cases. There is one judge and an appointed jury. The jury in Victor's case came to a unanimous decision that he was innocent.

It seems that the aristocratic party tended to favor those of high rank and often freed them disregarding any factual evidence (European Romantic Review). Mary Shelley may be suggesting that Victor's privileged rank may be the reason he was set free.

-

You, who call Frankenstein your friend, seem to have a knowledge of my crimes and his misfortunes. But in the detail which he gave you of them he could not sum up the hours and months of misery which I endured wasting in impotent passions. For while I destroyed his hopes, I did not satisfy my own desires. They were forever ardent and craving; still I desired love and fellowship, and I was still spurned. Was there no injustice in this? Am I to be thought the only criminal, when all humankind sinned against me? Why do you not hate Felix, who drove his friend from his door with contumely? Why do you not execrate the rustic who sought to destroy the saviour of his child? Nay, these are virtuous and immaculate beings! I, the miserable and the abandoned, am an abortion, to be spurned at, and kicked, and trampled on. Even now my blood boils at the recollection of this injustice.

Marshall Brown suggests that the sentiments expressed in this speech, intended to be directed at Walton, may extend to the reader as well. In his article, "Frankenstein: A Childs Tale," (http://web.a.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail/detail?sid=e8f7b0dc-662f-4ccc-8ec1-8c2ebfa5d291%40sessionmgr4008&vid=0&hid=4112&bdata=JkF1dGhUeXBlPWlwLHVpZCZzY29wZT1zaXRl#AN=12672272&db=aph) he asserts that Shelley's novel is a monster in itself. He expresses, "Frankenstein, then, is just as horrible as it seems. It plays with our sensibilities, like a child's game from the loser's perspective." That is to say, the reader is made to sympathize with the Creature and know what it feels like to be abandoned and misunderstood. Brown asserts that the Creature can be read as a neglected child-figure. Without proper education, it becomes impossible to fully blame him for his crimes. As Brown puts it, "it invalidates the moral questioning supporting ideological readings. In other books murder and mayhem may be subject to restorative justice or redemptive religion, but Frankenstein has a dark abyss at its core."

The Creature's speech may then serve the purpose to call any notions of black-and-white morality that the reader may hold. Considering that Shelley's novel as a whole holds the capacity to unsettle its reader with this same line of questioning, Brown goes on to extend the title of "Monster" to not only the Creature, but the very text itself.

Brown, Marshall. "Frankenstein: A Child's Tale." Novel: A Forum On Fiction 36.2 (2003): 145-175. Academic Search Premier. Web. 9 Dec. 2016.

-

I may there discover the wondrous power which attracts the needle and may regulate a thousand celestial observations that require only this voyage to render their seeming eccentricities consistent forever. I shall satiate my ardent curiosity with the sight of a part of the world never before visited, and may tread a land never before imprinted by the foot of man. These are my enticements, and they are sufficient to conquer all fear of danger or death and to induce me to commence this laborious voyage with the joy a child feels when he embarks in a little boat, with his holiday mates, on an expedition of discovery up his native river.

Claudia Rozas Gomez addresses this passage in her article, "Strangers and Orphans: Knowledge and mutuality in Mary Shelley's Frankenstein." (http://web.b.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=93864b1c-c2de-488e-9f82-3e3ebeb47ee9%40sessionmgr107&vid=1&hid=125) In the article, Gomez compares this sentiments to Victor's, the connection being that they both view knowledge in over-simplified terms in which, "the role of the learner is to obtain the knowledge or make the discovery, and then pass it on to others. It is not to engage or reflect critically in any way. Neither Victor nor Walton considers any negative outcomes of their respective quests. There is no expectation that the outcome could be anything other than what they have imagined it to be."

Not considering the ramifications of his scientific accomplishment led Victor to create a monster. Considering Walton and Victor's similar goals of advancement and discovery, it could be asserted that there would've been comparable ramifications were Walton to have continued his journey and succeeded. Victor's aborted second creature can then be seen as a strong parallel to Walton's aborted journey.

Gómez, Claudia Rozas. Strangers and orphans: Knowledge and mutuality in Mary Shelley's Frankenstein. Educational philosophy and theory 45.4 2013: 360-370. Blackwell Publishing. 09 Dec 2016.

-

I am going to unexplored regions, to "the land of mist and snow," but I shall kill no albatross; therefore do not be alarmed for my safety or if I should come back to you as worn and woeful as the "Ancient Mariner."

Here, Walton makes a direct reference to poetry and quotes Coleridge's "Rime of the Ancient Mariner." This further solidifies Walton's lack of formal education and shows his knowledge of poetry, instead.

-

"That is also my victim!" he exclaimed. "In his murder my crimes are consummated; the miserable series of my being is wound to its close! Oh, Frankenstein! Generous and self-devoted being! What does it avail that I now ask thee to pardon me? I, who irretrievably destroyed thee by destroying all thou lovedst. Alas! He is cold, he cannot answer me.

Without Walton's letters acting as a framing device, this scene would not have been possible. Walton's framing allows us to feel sympathy for the Creature. As stated earlier, if the story were told from Victor's point of view, the story would characterize the Creature as a monster. Victor is never able to see the Creature admit his guilt for destroying Victor and his family. Therefore, Walton is important to give truth to the story and show the Creature for who he really is: someone who is lonely and remorseful.

-

I am surrounded by mountains of ice which admit of no escape and threaten every moment to crush my vessel. The brave fellows whom I have persuaded to be my companions look towards me for aid, but I have none to bestow

Here, Walton seems to fully be accepting the danger that he has put his crew in. It becomes clear that Walton doesn't know what he is doing and he cannot help his crew. He got caught up in his books and thought that he could accomplish this journey, much like how Victor got caught up in his alchemy books and thought that he could create life. However, Walton must face the consequences of putting his crew in danger, as Victor faced the fact that he put his family in danger. Both also ultimately put themselves in danger.

-

"When younger," said he, "I believed myself destined for some great enterprise.

Earlier in the novel, in Walton's first set of letters, he says something very similar. Walton states, "And now, dear Margaret, do I not deserve to accomplish some great purpose? My life might have been passed in ease and luxury, but I preferred glory to every enticement that wealth placed in my path." This shows that Walton and Victor are similar in the sense that both believed that they were destined for something greater.

-

His tale is connected and told with an appearance of the simplest truth, yet I own to you that the letters of Felix and Safie, which he showed me, and the apparition of the monster seen from our ship, brought to me a greater conviction of the truth of his narrative than his asseverations, however earnest and connected.

Britton says that "sympathy determine's the novel's frame structure... As the frames open... each shift in both perspective and genre is simultaneous with an experience of sympathy." Walton frames the sympathy for Victor, who frames the sympathy for the Creature, who frames the sympathy for Safie's story. As Walton states here, this story is told with "an appearance of the simplest truth." As each character frames another character's story, we are able to see each story as being true. Without this framing device, the story would be told from one person's perspective and it would have been biased. This story naturally would have been told from Victor's perspective and he would have painted the Creature to be a monster. However, Walton frames everyone's stories and allows us to see the truth. As Britton states, "As those frames close, and as the text returns to its outermost level and original epistolary form, the impossibility of sympathy silences each voice and concludes each frame."

Britton, Jeanne M. “Novelistic Sympathy in Mary Shelley's ‘Frankenstein.’” Studies in Romanticism, vol. 48, no. 1, 2009, pp. 3–22. www.jstor.org/stable/25602177.

-

Strange and harrowing must be his story, frightful the storm which embraced the gallant vessel on its course and wrecked it—thus!

As scholar Jeanne M. Britton points out, thus far, Walton has been the "letter-writer and first-person narrator." Walton accepts Victor onto his ship and feels an immediate sympathy for him, and as stated earlier, Walton seems to find a much-needed friendship in Victor. As Victor begins his story, the novel switches to his perspective. We then hear the Creature's story and within that narrative, we also hear Safie's story. Britton says, "The process by which the monster can identify with Safie and, in the act of transcribing her letters, adopt her voice marks the limit of the simultaneous experience of sympathy and shift in perspective that allows Walton to speak for Frankenstein and Frankenstein to speak for his creature. But by generating this transcription of letters, the desire for a sympathetic experience that seems within reach also produces a physical document that attests to both the truth of the monster's tale and the narrative and novelistic functions that sympathy performs." Walton's letters frame the whole novel, but Victor's narration also frames the Creature's story, which frames Safie's story. Each of these frames gives us a new story and gives us a complete picture of the characters in this novel. If the story were told from one point of view, there would be no truth to the story, as it would be completely biased. Walton is our unbiased framing device.

Britton, Jeanne M. “Novelistic Sympathy in Mary Shelley's ‘Frankenstein.’” Studies in Romanticism, vol. 48, no. 1, 2009, pp. 3–22. www.jstor.org/stable/25602177.

-

I shall commit my thoughts to paper, it is true; but that is a poor medium for the communication of feeling. I desire the company of a man who could sympathize with me, whose eyes would reply to mine. You may deem me romantic, my dear sister, but I bitterly feel the want of a friend. I have no one near me, gentle yet courageous, possessed of a cultivated as well as of a capacious mind, whose tastes are like my own, to approve or amend my plans. How would such a friend repair the faults of your poor brother!

Here, Walton is expresses his loneliness by saying that communicating through paper is not enough. He wishes that he had a friend who could "sympathize" with him. He wants someone with similar tastes and someone who is "cultivated as well as of a capacious mind." OED defines "capacious" as "able to hold much; roomy, spacious, wide." Walton wants a companion who shares his ideologies and is of the same mind. He seems to be saying that he is all of these things, "gentle yet courageous," "cultivated," and has a "capacious mind." Therefore, he wants someone like him whom he can talk to. This becomes important when Victor boards the ship and the two become friends. Victor seems to be everything that Walton has wanted. Therefore, Walton seems to be foreshadowing the fact that he and Victor resemble each other. He so desperately wants an educated friend to share his thoughts with, and he gets this in Victor. The fact that Walton sees Victor of being worthy of being a friend suggests that Victor does indeed have these qualities and that Walton sees him as "cultivated." OED defines "cultivated" as "of a person or society: improved by education or training; refined." Only someone with Walton's background of having a neglected formal education would find Victor to be "cultivated."

-

my intention is to hire a ship there, which can easily be done by paying the insurance for the owner, and to engage as many sailors as I think necessary among those who are accustomed to the whale-fishing.

Here, Walton may be accepting that he doesn't actually know what he is doing. He needs to hire a ship and sailors, all of whom will hopefully know what they are doing more than Walton. Walton seems to accept that he might not be successful in this journey and that "If [he] fail[s], [his sister] will see [him] again soon, or never."

-

Now I am twenty-eight and am in reality more illiterate than many schoolboys of fifteen

Walton acknowledges that his formal education has been neglected and that he is "more illiterate than many schoolboys," but this doesn't seem to deter him from his journey. He seems to think that reading the books from his uncle's library is enough to teach him how to man a ship and find the Northern Passage. However, it later becomes clear that he was perhaps just reading poetry and that this will not be enough for him to complete this journey. Poetry does not give you the knowledge that you need to complete a journey like this. Walton's poetry resembles Victor's alchemy books that seem to encourage him to attempt to create life. Both characters seem to be reading fiction and accepting it as truth.

-

and my familiarity with them increased that regret which I had felt, as a child, on learning that my father's dying injunction had forbidden my uncle to allow me to embark in a seafaring life.

Walton seems to be using this journey to find the Northern Passage as a way to make up for a lost childhood of sorts. He spent his childhood reading about these voyages from his uncle's library and feels "regret" that his father had forbidden him from "embark[ing] in a seafaring life." Earlier in this letter, he also states that he will "commence this laborious voyage with the joy a child feels when he embarks in a little boat." Walton doesn't seem to be accepting the dangers of this journey and is simply fulfilling a childhood dream of his. Beck also attributes these quotes to Walton's immaturity.He also states that Walton resembles Victor because, "in their 'scientific' explorations, they are both driven by the same kind of prelapsarian (Miltonic) fantasy and by the same kind of absolutionist utopian desire: to start afresh from a point in time before the Fall, to find a shortcut out of history and thus to become benefactors of mankind." Victor does this by trying to create life, while Walton fails "to create a permanent Paradise of his own by literary means," and instead decides to embark on this journey and attempt to return to his childhood innocence.

Beck, Rudolf. “‘The Region of Beauty and Delight’: Walton's Polar Fantasies in Mary Shelley's ‘Frankenstein.’” Keats-Shelley Journal, vol. 49, 2000, pp. 24–29. www.jstor.org/stable/30213044.

-

I also became a poet and for one year lived in a paradise of my own creation

In his article "‘The Region of Beauty and Delight’: Walton's Polar Fantasies in Mary Shelley's ‘Frankenstein,’” Beck characterizes Walton as being someone with a "boyish immaturity," with the desire to "(re-)enter Paradise" and live as a poet again. Beck points out that Walton's formal education was neglected and that he turned to books as a source of knowledge. This included books of poetry and suggests that Walton's idea of the real world has been altered by the books he has read. As stated in an earlier annotations, Beck suggests that Walton's image of the North Pole comes from Milton's Paradise Lost. Therefore, it doesn't seem as if Walton completely has a hold of reality. Much like Victor, he seems to be slipping, as far as education goes. Victor held his alchemy books dearly to be the truth and Walton seems to be doing the same for books of poetry. Books seem to give people their paradise, or even their reality, in this novel.

Beck, Rudolf. “‘The Region of Beauty and Delight’: Walton's Polar Fantasies in Mary Shelley's ‘Frankenstein.’” Keats-Shelley Journal, vol. 49, 2000, pp. 24–29. www.jstor.org/stable/30213044.

-

What may not be expected in a country of eternal light?

Scholar Rudolf Beck attributes Walton's imagined North Pole to be a reference to Milton's "Paradise Lost." He says, "There can hardly be any doubt that Walton's vision of a 'country of eternal light,' and even more specifically, his idea of a permanently visible sun with its 'broad disk just skirting the horizon and diffusing a perpetual splendour,' corresponds directly to Milton's special-case 'prelapsarian astronomy." Beck attributes this to Walton's lack of a formal education. Walton seems to have learned much of what he has learned on his own from books. This relates him to both Victor and the Creature. Victor studied alchemy on his own, which gave him the "knowledge" he needed to create life. However, the Creature actually reads "Paradise Lost" in the novel and this is where he gets his ideas about a creator and needing a partner in life. All of these characters seem to be doing their own "research" and learning which may lead to their downfall.

Beck, Rudolf. “‘The Region of Beauty and Delight’: Walton's Polar Fantasies in Mary Shelley's ‘Frankenstein.’” Keats-Shelley Journal, vol. 49, 2000, pp. 24–29. www.jstor.org/stable/30213044.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.bartleby.com www.bartleby.com

-

Percy Bysshe Shelley

Husband of Mary Shelley who is the author of Frankenstein. (562).

Richards, Irving T. “A Note on Source Influences in Shelley's Cloud and Skylark.” PMLA, vol. 50, no. 2, 1935, pp. 562–567. www.jstor.org/stable/458158.

-

Sublime on the towers of my skiey bowers

sublime is thought of as the excitement that comes from fearful events.

-

crimson

A deep red color.

-

I bind the sun’s throne with a burning zone, And the moon’s with a girdle of pearl;

The cloud protects the earth and all that is on it from the suns harmful rays and from the moon. It is protecting the creation under its care. https://letterpile.com/poetry/Summary-of-The-Cloud-1820-by-Percy-Bysshe-Shelly

-

behind her

Her refers to the moon. The stars are like the children of the moon.

-

torrent sea,

A strong body of water

-

blue dome of air,

Describes the sky.

-

mountain crag

The edge of a mountain that sticks out.

-

I bind the sun’s throne with a burning zone, And the moon’s with a girdle of pearl;

The cloud protects the earth and all that is on it from the suns harmful rays and from the moon. It is protecting the creation under its care. https://letterpile.com/poetry/Summary-of-The-Cloud-1820-by-Percy-Bysshe-Shelly

-

I change, but I cannot die.

The cloud changes and morphs over time but never disappears or can be destroyed. Its life cycle is one that is never ending but rather changing.

https://letterpile.com/poetry/Summary-of-The-Cloud-1820-by-Percy-Bysshe-Shelly

-

orbèd

circular.

-

sanguine sunrise

cheerful, positive

-

The Cloud

The cloud is not inclusive to just plants and animals. People experience the effects of the cloud as well.

Taylor, Beverly. “SHELLEY'S PHILOSOPHICAL PERSPECTIVE AND THEMATIC CONCERNS IN ‘THE CLOUD.’” Interpretations, vol. 12, no. 1, 1980, pp. 70–75. www.jstor.org/stable/23240551.

-

In a cavern under is fretted the thunder, It struggles and howls at fits

The talk of storms in the poem is thought to be influenced by Robert Herrick's The Hag.

Richards, Irving T. “A Note on Source Influences in Shelley's Cloud and Skylark.” PMLA, vol. 50, no. 2, 1935, pp. 562–567. www.jstor.org/stable/458158.

-

I am the daughter of earth and water, And the nursling of the sky;

The cloud is represented as an authority or mother figure taking care of the earth by bringing fresh water. Shelley is also scientifically backing up the cycle a cloud goes through by using weather to describe it.

Taylor, Beverly. “SHELLEY'S PHILOSOPHICAL PERSPECTIVE AND THEMATIC CONCERNS IN ‘THE CLOUD.’” Interpretations, vol. 12, no. 1, 1980, pp. 70–75. www.jstor.org/stable/23240551.

-

Lightning my pilot sits,

During this time, scientists were studying electricity and were fascinated with idea of it being the source of life.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.gutenberg.org www.gutenberg.org

-

They were a boy and girl. Yellow, meagre, ragged, scowling, wolfish; but prostrate, too, in their humility. Where graceful youth should have filled their features out, and touched them with its freshest tints, a stale and shrivelled hand, like that of age, had pinched, and twisted them, and pulled them into shreds. Where angels might have sat enthroned, devils lurked, and glared out menacing. No change, no degradation, no perversion of humanity, in any grade, through all the mysteries of wonderful creation, has monsters half so horrible and dread.

According to author Robert D. Butterworth, critic Thomas Hood was very concerned with the Poor Law and it's operations involving the prisons and work houses. The authorities of these facilities would ensure the dehumanization of its workers, who were already humiliated in having no choice but to go there (Butterworth, 432). This dehumanization stemmed from family separation, lack of free expression, and long work hours with much limitation on meals since the authorities were cheap about the costs. The dehumanization is shown in the two children within the folding of the ghost who appear hideous and show animal-like behavior. They represent the poor class that seem so frightening because of the ignorance of those with higher status, like Scrooge, who neglected them as people, sparing no provisions or donations when needed.

-

There never was such a goose. Bob said he didn’t believe there ever was such a goose cooked. Its tenderness and flavour, size and cheapness, were the themes of universal admiration. Eked out by apple-sauce and mashed potatoes, it was a sufficient dinner for the whole family;

According to Tara Moore, author of Starvation In Victorian Christmas Fiction, the novel by Dickens conveys the role food plays in determining the ethnic and class identity of the Cratchit family (Moore, 498). Compared to the list of foods a family of should typically have at Christmas dinner, the Cratchits had the minimal amount, with goose, apple sauce, mashed potatoes, and pudding. This exploited their low class status as the wife and kids all stayed home to prepare the meal throughout the day. However this meal was still sufficient for the whole family as they found the power of joy to be within themselves and their love for each other rather than in the manifestations of the holiday itself.

-

“There are some upon this earth of yours,” returned the Spirit, “who lay claim to know us, and who do their deeds of passion, pride, ill-will, hatred, envy, bigotry, and selfishness in our name, who are as strange to us and all our kith and kin, as if they had never lived. Remember that, and charge their doings on themselves, not us.”

The Ghost of Christmas Present suggests that Scrooge should acknowledge those who mean well by him and credit them for their work under his authority. Dickens lived in a society where businesses would attempt to lessen the obligations owed to those would did their work (Sullivan, 934). Referring back to the novel, we see this idea conveyed through Scrooge's commentary on the justice that he thinks the prison and work place provide for the poor, lower class. The reference along with the Ghost's suggestion also parallels how Scrooge treats his clerk Bob Cratchit, paying him low wages for as much work as he has Bob do for him. Yet Scrooge never seems to feel obliged towards Crachit regardless.

-

But they didn’t devote the whole evening to music. After a while they played at forfeits; for it is good to be children sometimes, and never better than at Christmas, when its mighty Founder was a child himself.

In reference to the birth of Christ in the manger. Christmas was to bring much merriment as the birth of Christ brought joy to the world.

-

Plenty’s horn

Plenty's Horn refers to a cornucopia, a large horn shaped object overflowing with produce. It symbolized an abundance of nourishment, particularly associated with giving thanks and being joyous. This is the same kindness the Ghost of Christmas Present bestows upon those in the town who were quarreling on the way to church, returning joy to their soul.

-

Gentlemen of the free-and-easy sort, who plume themselves on being acquainted with a move or two, and being usually equal to the time-of-day, express the wide range of their capacity for adventure by observing that they are good for anything from pitch-and-toss to manslaughter; between which opposite extremes, no doubt, there lies a tolerably wide and comprehensive range of subjects.

According to the article Retelling of A Christmas Carol even though Charles Dickens was poor when he was young, at the time of writing Carol he was ashamed to be part of such lower class and thus prided himself among reaching out to his now fellow middle class citizens. Angered by pirates, who called themselves artistic collaborators and re-originated his novel, Dickens eagerly desired to take full authorship of his work (Davis, 112). However such pirates, filled with greed and vulgarity, were able to confront Dickens, suggesting that his writing was not a way to escape his cruel past. Dickens spoke on preventing the copyright of British works by American publishers which made hims seem self-serving in the eye of the American media, as the so called pirates who were copying his novel came forth as his collaborators and were able to reach the lower class by way of cheaper illustration, popularizing Dickens's novel even more (Davis, 113). The vulgar nature of the pirates, and Dickens's supposed obsession with authorship and royalties place them parallel to the free-and-easy sort of gentlemen in A Christmas Carol, like Scrooge, who deem it necessary capable of any endeavors they decide to carry out. The similarities convey Scrooge's selfish behavior, supplying charity to the labor house and prison which he he supports, instead of also giving donations for the poor, which in this case could be deemed indirect manslaughter, as the prison and workhouse conditions were of ill status.

-

A CHRISTMAS CAROL

References for further reading:

Butterworth, Robert D. "THOMAS HOOD, EARLY VICTORIAN CHRISTIAN SOCIAL CRITICISM, AND THE HOODIAN HERO | Victorian Literature and Culture | Cambridge Core." Cambridge Core. Cambridge University Press, 2011. Web. 09 Dec. 2016. https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/S1060150311000076.

Davis P. Retelling A Christmas Carol. American Scholar [serial online]. Winter90 1990;59(1):109. Available from: Historical Abstracts, Ipswich, MA. Accessed December 9, 2016.

Moore, Tara. "STARVATION IN VICTORIAN CHRISTMAS FICTION | Victorian Literature and Culture | Cambridge Core." Cambridge Core. Cambridge University Press, 2008. Web. 09 Dec. 2016. https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/S1060150308080303.

Sullivan, Barry, A Book that Shaped Your World: Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol (October 1, 2013). Alberta Law Review, Vol. 50, No. 4, 2013; Loyola University Chicago School of Law Research Paper No. 2013-024. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2369511

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.gutenberg.org www.gutenberg.org

-

For there is no friend like a sister, In calm or stormy weather, To cheer one on the tedious way, To fetch one if one goes astray, To lift one if one totters down, To strengthen whilst one stands

Another possible piece of evidence for a feministic theme. Most of the female poets and authors succeeding Barbauld can be attributed to furthering the feminist wave and coincidentally, women gained suffrage in Britain less than a century after the publication of Goblin's Market.

-

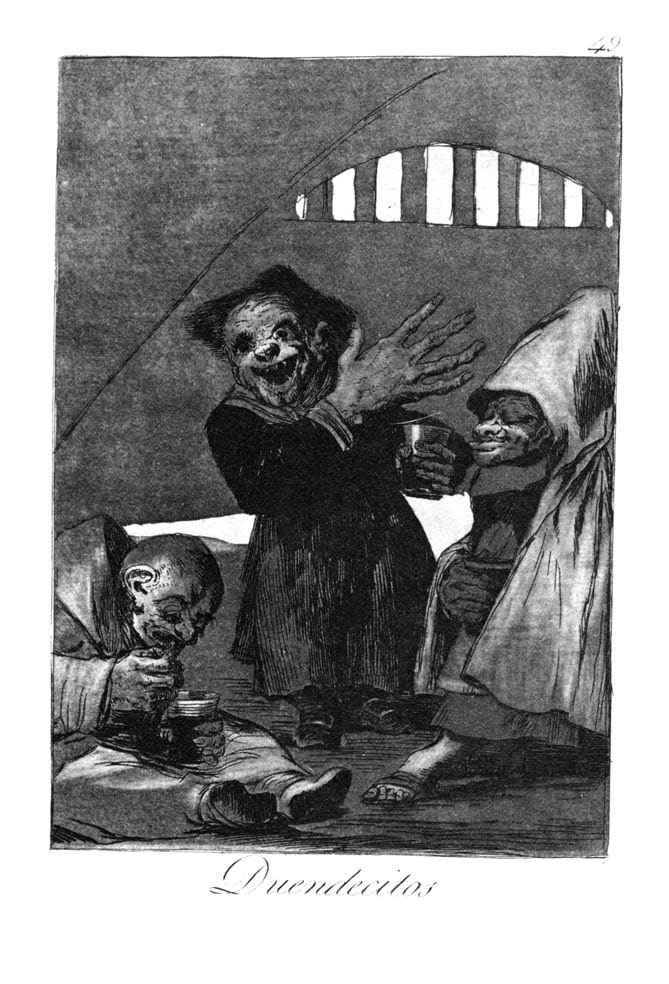

goblins

Goblins are characters of British and Germanic folklore as well as Latin and Greek mythology. They are considered evil and characteristically mischievous across most interpretations. Below is a painting titles "Little Goblins" by Goya. http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Goblin

-

One had a cat's face, One whisked a tail, One tramped at a rat's pace, One crawled like a snail, One like a wombat prowled obtuse and furry, One like a ratel tumbled hurry-scurry. She heard a voice like voice of doves

This can be interpreted as Rossetti making the villains of the poem more child-friendly. Another interpretation is that much like the biblical demons, the goblins take on facades to make them seem more likeable.

-

moonlight

Another example of sexual reference. The night is often related to passion as well as of functioning in a sexual profession. Purchasing fruits in the moonlight is also unusual, perverting the interaction with the goblins further.

-

Chuckling, clapping, crowing, Clucking and gobbling, Mopping and mowing, Full of airs and graces, Pulling wry faces, Demure grimaces, [15]Cat-like and rat-like, Ratel and wombat-like, Snail-paced in a hurry, Parrot-voiced and whistler, Helter-skelter, hurry-skurry, Chattering like magpies, Fluttering like pigeons, Gliding like fishes,-- Hugged her and kissed her; Squeezed and caressed her;

The poem is often described as being inappropriately for children, lines like this which are examples of alliteration, give the poem a dancing quality which makes it child-friendly. Much like there is little to no direct reference to Christianity, there are no direct sexual references, only interpretations.

-

fruit forbidden

This is one of the only few instances of a reference to Genesis. It is inverted only to rhyme with the next line. It's important to note that one of the only uses of this term is said by Laura, the one afflicted for eating the fruit. Even then, the term Forbidden Fruit isn't used in the bible. It is more of a cultural metaphor for the situation in Genesis and sources of temptation in general.

http://openprairie.sdstate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1977&context=etd

-

She fell at last; Pleasure past and anguish past,

These lines sound akin to a refractory period after sex, which furthers the sexuality interpretation of this poem.

-

Life out of death.

Rebirth, perhaps furthering the religious sub-tone.

-

Apples

Perhaps Rossetti placed apples first in the list in order to evoke images of the book of Genesis. Most religious interpretations arise from this and the theme of temptation is applicable to the character of Laura. However, the procession of fruits and the lack of direct christian reference in the poem can lead to other interpretations.

-

GOBLIN MARKET

Everett, Glenn. "The Life of Christina Rossetti." The Victorian Web. N.p., 1988. Web. 09 Dec. 2016. http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/crossetti/rossettibio.html.

Farhana, Jannatul. "Revolutionary Poetic Voices of Victorian Period: A Comparative Study between Elizabeth Barrette Browning and Christina Rossetti." English Language and Literature Studies 6.1 (2016): 69. Web. http://www.ccsenet.org/journal/index.php/ells/article/viewFile/57703/30859.

Mihajlovic, Randi, "Queering the Spheres: Non-Normative Gender, Sexuality, and Family in Three Victorian Texts" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. Paper 974. http://openprairie.sdstate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1977&context=etd.

-

-

www.bartleby.com www.bartleby.com

-

Then came some palsied oak, a cleft in him Like a distorted mouth that splits its rim 155 Gaping at death, and dies while it recoils.

In the second half of this stanza, our narrator describes the image of an unsightly oak tree.

-

Alive? he might be dead for aught I know, With that red, gaunt and collop’d neck a-strain, 80 And shut eyes underneath the rusty mane; Seldom went such grotesqueness with such woe; I never saw a brute I hated so; He must be wicked to deserve such pain.

Throughout this stanza (80), Browning continues to describe the image of the half dead horse, as well as the orator's own befuddlement and dread toward the apparent validity of its actual existence. In other words, we see our orator begin to question what he see's. We will see this theme of madness continually being referenced and strengthen through the remaining progression of the poem.

-

One stiff blind horse, his every bone a-stare, Stood stupefied, however he came there: Thrust out past service from the devil’s stud!

This three lines of stanza 75 personify the sudden image of a sickly horse.The description contains striking parallels to the well-known Medieval Age Horses of the Apocalypse myth. In particular, the apocalypse horse of Famine. This makes sense considering the previously described wasteland. The image further amplifies the reader's personification of both the wasteland and Browning's overall Medieval theme of the poem.

-

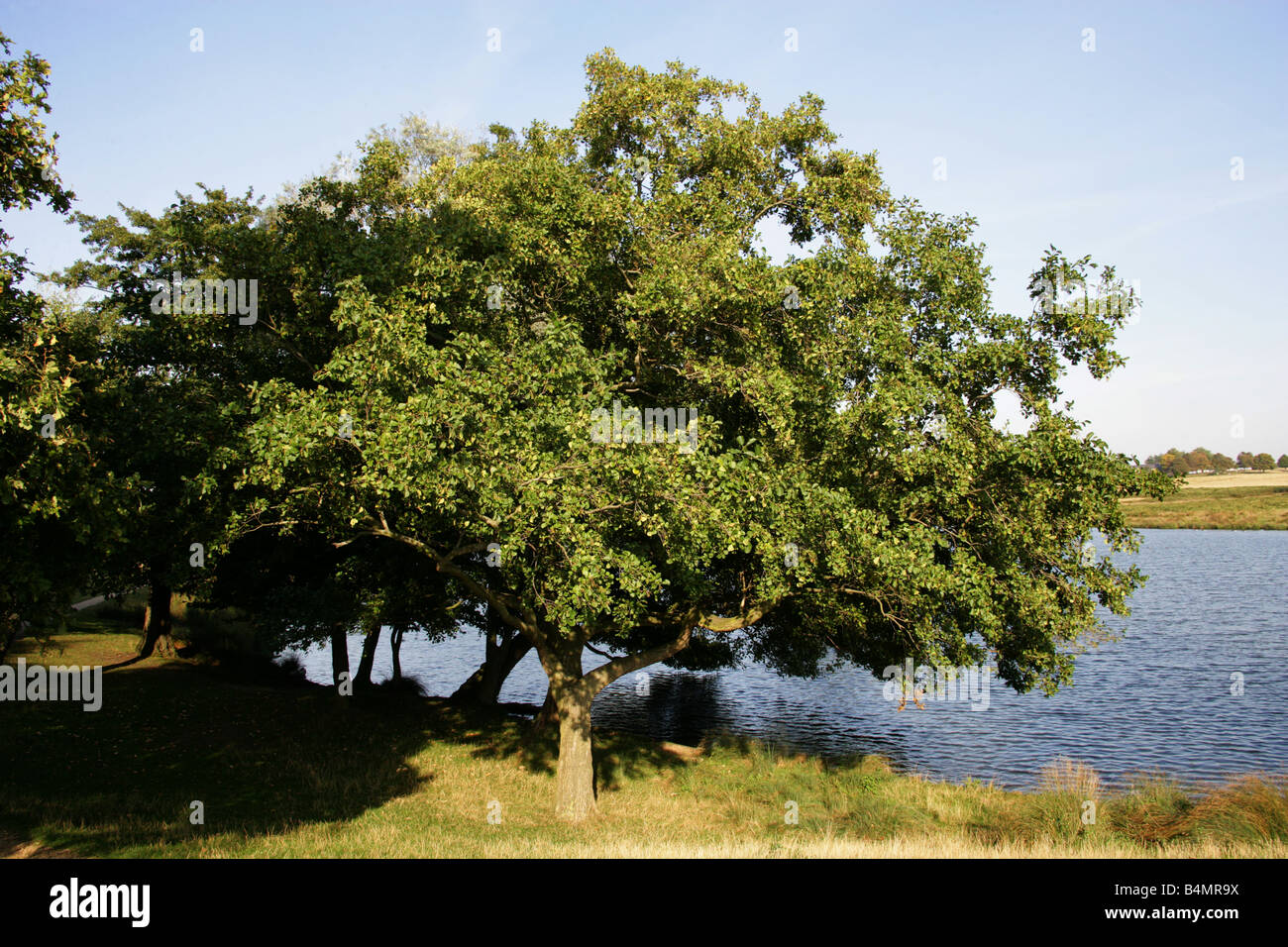

Was settling to its close, yet shot one grim Red leer to see the plain catch its estray.

These two final lines of stanza 45 are just the orator's realization and distinct description of the coming dawn. The orator makes note of the reddish colored sky being "pulled away" by the surrounding wasteland. It should be noted that Browning's probable, intended vision was one similar to the exampled photograph.

-

There they stood, ranged along the hill-sides, met To view the last of me, a living frame 200 For one more picture! in a sheet of flame I saw them and I knew them all. And yet Dauntless the slug-horn to my lips I set,

As the poem finalizes, we get a visual scene of Roland crying out upon his, somewhat "forced" discovery of the Dark Tower. Yet we (the reader), are left with an eerie and ambiguous sense of negative capability as the poem immediately concludes and questions are raised ragarding Roland's looming madness.

-

A sudden little river cross’d my path As unexpected as a serpent comes.

One of the key themes of this poem is the use of illusion through landscape. This plays further into Roland's (our narrator) mental stability, as we get the impression he sudden comes across a somewhat "random" river.

-

Not see? because of night perhaps?—Why, day Came back again for that! before it left, The dying sunset kindled through a cleft: The hills, like giants at a hunting, lay, 190 Chin upon hand, to see the game at bay,—

Browning means to compare Roland's vision of the Dark Tower to an illusion, much like the famed "desert mirage", as in darkness, he sees a sudden flash of light.

-

MY 1 first thought was, he lied in every word, That hoary cripple, with malicious eye Askance to watch the working of his lie On mine, and mouth scarce able to afford Suppression of the glee, that purs’d and scor’d 5 Its edge, at one more victim gain’d thereby

The poem opens with our narrator, Roland, irritated at the intentional wrong directions given to him by a "hoary cripple, with malicious eye." Lines 5-6 see Roland imaging the old man's glee, leading Roland astray with dishonest directions.

-

Not hear? when noise was everywhere! it toll’d Increasing like a bell. Names in my ears Of all the lost adventurers my peers,— 195 How such a one was strong, and such was bold, And such was fortunate, yet each of old Lost, lost! one moment knell’d the woe of years.

Roland is hearing spectral voices of lost adventures and old friends upon his (supposed) discovery of the Tower. But one must raise an eyebrow to these voices's actual existence. It is here, withing the last stanza of Browning poem, that one could strongly argue Roland's sanity, and the validity of his discovery. However, Browning does not distinctly verify Roland's mental condition, and brilliantly leaves the reader with a sense of subjective interpretation.

-

What in the midst lay but the Tower itself? The round squat turret, blind as the fool’s heart, Built of brown stone, without a counter-part In the whole world. The tempest’s mocking elf Points to the shipman thus the unseen shelf 185 He strikes on, only when the timbers start.

Browning makes a beautiful allegory here following the supposed discovery of the Dark Tower by Roland, our narrator. In his moment of utter disparity, much like a sailor at sea trapped in a raging storm, who finds land as his ship begins to break apart, Roland spies the Dark Tower.

-

tempest’s mocking elf

A tempest is a massive storm (usually occurring at sea), while the word "elf" here implies something of trickery or mischievous.

-

Burningly it came on me all at once, 175 This was the place! those two hills on the right, Couch’d like two bulls lock’d horn in horn in fight, While, to the left, a tall scalp’d mountain … Dunce, Dotard, a-dozing at the very nonce, After a life spent training for the sight!

Suddenly, our narrator spies what (might be) the Dark Tower!

-

Yet half I seem’d to recognize some trick Of mischief happen’d to me, God knows when— 170 In a bad perhaps. Here ended, then, Progress this way. When, in the very nick Of giving up, one time more, came a click As when a trap shuts—you ’re inside the den.

Our narrator and protagonist is clearly, aimlessly wondering about in the labyrinth of mountains. Yet just as he continually approaches the edge of defeat, he finds a sudden "click" of inspiration, pushing him forward. Browning is never clear as to what this inspiration actually is, purposely aiding to the subjective interpretation of the reader.

-

For, looking up, aware I somehow grew, Spite of the dusk, the plain had given place All round to mountains—with such name to grace 165 Mere ugly heights and heaps now stolen in view. How thus they had surpris’d me,—solve it, you! How to get from them was no clearer case.

In this stanza, our narrator, continuing on his quest to seek the Dark Tower, suddenly comes to a change in scenery, as he exists a wooded area into a mountainous region. What's interesting here, is that he doesn't actually realize the dramatic change in topography; once again implying questionable elements of his mental stability.

-

At the thought, A great black bird, Apollyon’s bosom-friend, 160 Sail’d past, nor beat his wide wing dragon-penn’d That brush’d my cap—perchance the guide I sought

Our narrator, struggling with the will to continue his quest/journey, sees a black bird (mostly likely a crow or carrion), which he interprets as the devil's guide. This vision, of a demonic black bird, again raises the question of our narrator's sanity. As readers, we begin to wonder if our protagonist realizes his own mental instability, as he willing pursues his "cursed" quest.

-

Apollyon

According to the OED (Oxford English Dictionary), "Apollyon" is another name "given to the Devil or destroyer."

-

palsied

According to the OED (Oxford English Dictionary), the word "palsied" is described as something "paralyzed" or "deprived of muscular energy or power of action; rendered impotent; tottering, trembling."

-

Then came a bit of stubb’d ground, once a wood, 145 Next a marsh, it would seem, and now mere earth Desperate and done with; (so a fool finds mirth, Makes a thing and then mars it, till his mood Changes and off he goes!) within a rood— Bog, clay, and rubble, sand and stark black dearth

Here, again, Browning mixes descriptive language and subliminal allegory to personify the destruction of nature. This theme is an underlying motif within the poem, as deforestation and natural pollution at the hands of a rapidly growing industrial England, and their associated effects on the surrounding land/nature are becoming serious issues within both England and Europe in the second half of the 19th Century. In addition, our narrator makes a comparison to this destructive theme and earth itself to a "fool who finds mirth"(happiness/joy) in making something, only to "mars it" (destroy it).

-

And more than that—a furlong on—why, there! What bad use was that engine for, that wheel, 140 Or brake, not wheel—that harrow fit to reel Men’s bodies out like silk?

Browning is making an interesting comparison here. Our narrator, upon continuing his travels, see the remains of war machines/engines, to which effects he parallels to an agricultural harrow, tearing the earth's soil like "men's bodies out like silk." Browning specifically references silk for two reasons; both its delicacy and fluidity, both of which are applicable to human physicality and disposition.

-

harrow

According to the OED (Oxford English Dictionary), a "harrow" is defined as "a heavy frame of timber (or iron) set with iron teeth or tines, which is dragged over ploughed land to break clods, pulverize and stir the soil, root up weeds, or cover in the seed."

-

furlong

According to the OED (Oxford English Dictionary), a "furlong" is described as "the length of the furrow in the common field, which was theoretically regarded as a square containing ten acres."

-

Who were the strugglers, what war did they wage Whose savage trample thus could pad the dank 130 Soil to a plash? Toads in a poison’d tank, Or wild cats in a red-hot iron cage— The fight must so have seem’d in that fell cirque. What penn’d them there, with all the plain to choose? No foot-print leading to that horrid mews, 135 None out of it. Mad brewage set to work Their brains, no doubt, like galley-slaves the Turk Pits for his pastime, Christians against Jews.

These two stanzas portray our narrator's interpretation following the grimly remains of a battle. As he questions each side and their represented motives', he compares the battle to a watery prison, where participants fought with hatred/resentment against their enemy. Browning makes a comparison to such resentment, by paralleling the ancient religious struggle between Christians, Muslims ("Turks") and Jews.

-

mews

According to the OED (Oxford English Dictionary), the word "mew" is defined as a "place of confinement, a cage, or a prison."

-

-

knarf.english.upenn.edu knarf.english.upenn.edu

-

670

Works CitedArtUK. Robert Fowler, 2010, http://artuk.org/discover/artists/fowler-robert-18531926. Accessed 21 Nov. 2016.

Baker C. & Clark D. L. “Literary Sources of Shelley’s The Witch of Atlas”. PMLA. 56:2, 472-494. JSTOR.

Bio. Mary Shelley Biography, 2016, http://www.biography.com/people/mary-shelley 9481497#related-video-gallery. Accessed 21 Nov. 2016.

Britton, J. M. “Sympathy in Mary Shelley’s ‘Frankenstein’.” Studies in Romanticism. 48:1 (May, 2009). JSTOR.

Fleck, P. D. “Shelley’s Notes to Shelley’s Poems and ‘Frankenstein’.” Studies in Romanticism. 6:4 (August, 1987). JSTOR.

Goulding, C. “Percy Shelley, James Lind, and The Witch of Atlas.” Notes and Queries. 50:3 (September 2016), 309-311. JSTOR.

Hogle, J. “Metaphor and Metamorphosis in Shelley’s ‘The Witch of Atlas’”. Studies in Romanticism. 19:3 (1990), 327-353. JSTOR.

Shelley’s Ghost. Shelley, draft of The Witch of Atlas, http://shelleysghost.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/the witch-of-atlas-draft#Description. Accessed 21 Nov. 2016.

Shelley, M. Frankenstein. 2008. Project Gutenberg’s Frankenstein. Web. 9 December 2016.

-

visionary rhyme.

According to Fleck from Boston University, in his article “Mary Shelley’s Notes to Shelley’s Poems”, Mary divided Percy’s poems into two categories for this publication , the purely imaginative and the ones that “spring from the emotions of the heart” saying: “[Mary] Shelley wrote ‘Shelley gave the reins to his fancy, and luxuriated in every idea as it rose…there is a sense of mystery which formed essential portions of his perception of life—a clinging to the subtler inner spirit, rather than to the outward form’…Mary saw in [the Witch of Atlas] Shelley’s preoccupation with the operations of the human mind” (Fleck, p. 229). This “preoccupation” seems obvious through the reading of this poem. Not only is the imagery and description very imaginative, Percy also focuses on the learning power of dreams and sleep as a reflection of mankind and how dreams effect the human mind. His "visionary rhyme" is much more than that.

-

Then by strange art she kneaded fire and snow Together, tempering the repugnant mass With liquid love -- all things together grow

This is the Witch's attempt at creation. She uses the elements (fire and snow) and "liquid love" to create her new being. It is beautiful, and graceful, and full of "perfect purity". In stanza XXXVII, the creature is described as having wings and seems to be more angel than demon.

-

XXIII.

This stanza highlights the destruction her creatures can cause. While they are beautiful and loyal, they are draining the springs, destroying mountains, and consuming the ocean and the Witch states that this "may not be" and that she cannot keep loving them until they both die. This is her first experience with the disaster of playing god.

-

The Witch of Atlas

This poem was published in 1824 in the larger work Posthumous Poems. The first published edition was edited by Percy's wife and fellow author Mary Shelley. Percy Shelley is said to have written the poem in only 3 days, during a journey through Italy. Oxford University has pages of the original draft of this poem, including images of sailors and boats drawn by Shelley. The images may be depictions of the Witch's river journey later in the poem.

-

And she would write strange dreams upon the brain

This is another example of the Witch playing god. With specific mortals, she takes them after death and puts them into and type of unaging sleep. She then writes dreams on their brains. They aren't bad dreams; she seems to be righting the wrongs of life in death. One example is, line 623 "The miser in such dreams would rise and shake Into a beggar's lap;". In this line, the Witch seems to be taking from the rich to give to the poor, even if it is just in a dream. Despite her good intentions, is it okay for her to play god?

-

She called "Hermaphroditus!"

This, I think, is a reference to her creature. Previously, the creature was described as being "sexless" and containing the gracefulness of both genders. A hermaphrodite is an "an individual in which reproductive organs of both sexes are present" or "an organism, as an earthworm or plant, having normally both the male and female organs of generation" (Dictionary.com).

-

And she saw princes couched under the glow Of sunlike gems; and round each temple-court In dormitories ranged, row after row, She saw the priests asleep -- all of one sort -- For all were educated to be so. -- The peasants in their huts, and in the port The sailors she saw cradled on the waves, And the dead lulled within their dreamless graves.

In these lines, like the other descriptions of sleep, Shelley uses where the humans are sleeping to describe them. The Witch sees the princes asleep alone under gems, the priests asleep in rows like "all were educated to be so", and the peasants in their huts, the sailors on the waves, and the dead in "dreamless graves". Shelley, again uses sleep to described the factions of society. We are all the same in sleep, but where we sleep can represent who we are awake. These was some of my favorite lines in the poem.

-

Mortals subdued in all the shapes of sleep.

In the following stanzas (LXI, LXII, LXIII, LXIV, and LXV) the Witch, through her journey as a star, sees all "all the shapes of sleep". Shelley, interestingly, represents the varied states of man all through their images of sleep. He represets innocence through the sleeping twins, sadness by the "lone youth" who cries in his sleep, love through the lovers, and the "calm old age". Shelley also represents the dark side of humanity and the Witch describes those as "distortions foul of supernatural awe". By showing the bright side of humanity through examples and only stating the dark, Shelley is showing that the light is stronger and more important to recognize.

-

Chasing the rapid smiles that would not stay, And drinking the warm tears, and the sweet sighs Inhaling, which, with busy murmur vain, They had aroused from that full heart and brain.

Shelley decides to comment on the intelligence of the "the Image" in line 368: he states, "[the dreams] had aroused [warm tears and sweet sighs] from that full heart and brain". The image or creature, is an intelligent and feeling being. This is an important aspect to note about her creation. This puts the creature more in line with humans than with animals.

-