The Passages of Paris and Benjamin's Mind by Herbert Muschamp details the rich history surrounding Benjamin's "Arcades Project" and the influence it had on the city of Paris. Though left incomplete on Benjamin's death in 1940, "The Arcades Project" nevertheless remains one of the most important urban analyses of the time. Benjamin was born to a Jewish art dealer in Berlin. He was educated there, but the Paris Arcade Project began in 1927 as a newspaper article. The manuscript was recovered by essayist George Batailles and was later taken to the Bibliotheque National in Paris. In the many sections of his analysis, Benjamin included both his own reflections and a vast amount of research material, which includes passages from other historical and architectural sources. Benjamin considered this type of building the most important during his time period because they signaled the end of an age production and the beginning of an era of consumption.

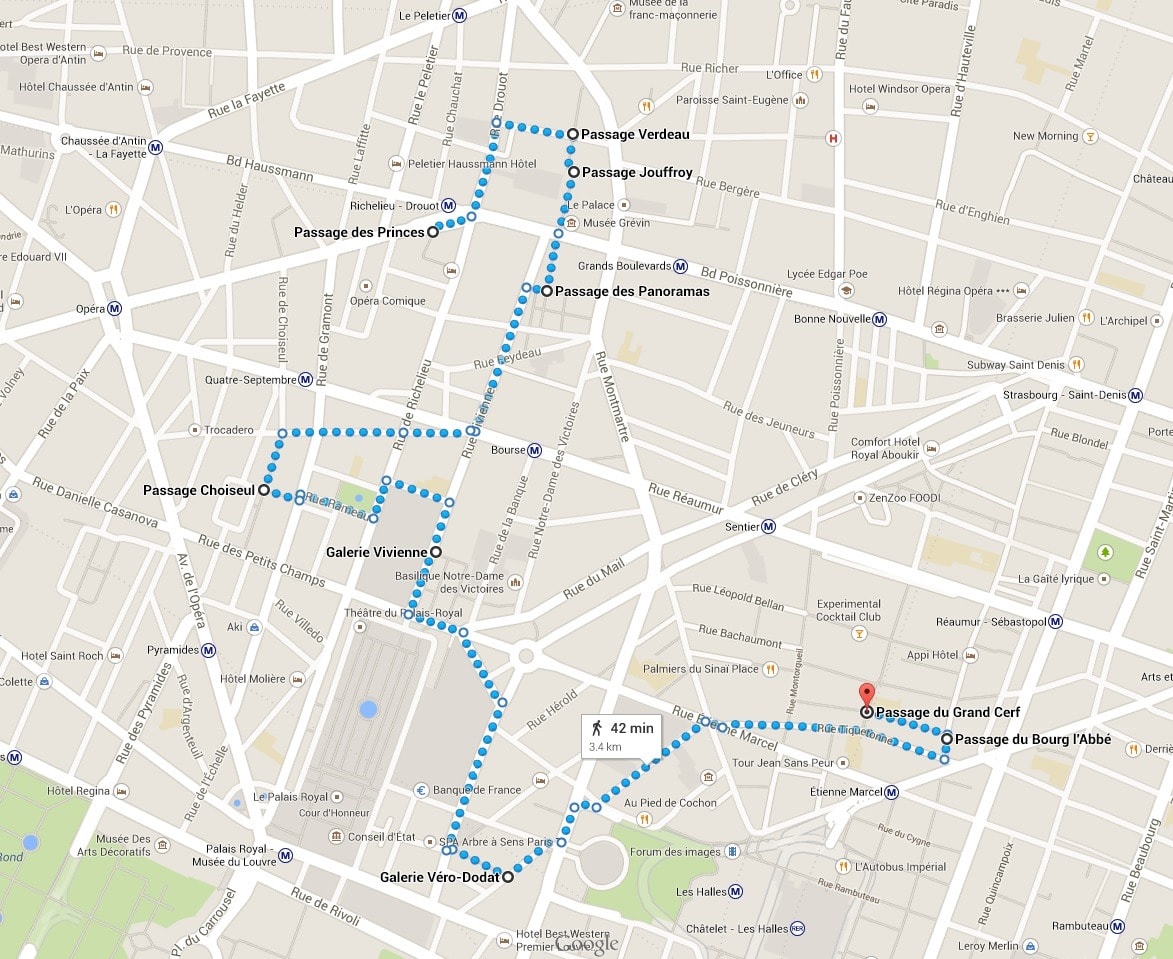

The article describes the arcade as a building type that predated Haussmann's grand boulevards. Essentially, the arcades were pedestrian passages between buildings--alleyways with iron and glass roofs over top of them. They were typically lined with shops and small restaurants, or tea rooms. The other even goes so far to describe the arcades as "the embryo of the suburban mall." Surprisingly, the arcades had been left behind, for the most part, when Benjamin was in Paris, Haussmann Boulevards having ripped through Paris to make room for new urban fantasies. Benjamin, however, was still a bit stuck on the old ones. He remains fixed on the "phantasmagoria" that exists in the arcades, and his criticism aims to bring awareness to his readers and "release them from the hold of manufactured states of mind," which are oftne proliferated by the architects of this age.

Muschamp, Herbert. "The Passages of Paris And of Benjamin's Mind." The New York Times. The New York Times, 16 Jan. 2000. Web. 10 Oct. 2016.

(

(