Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971

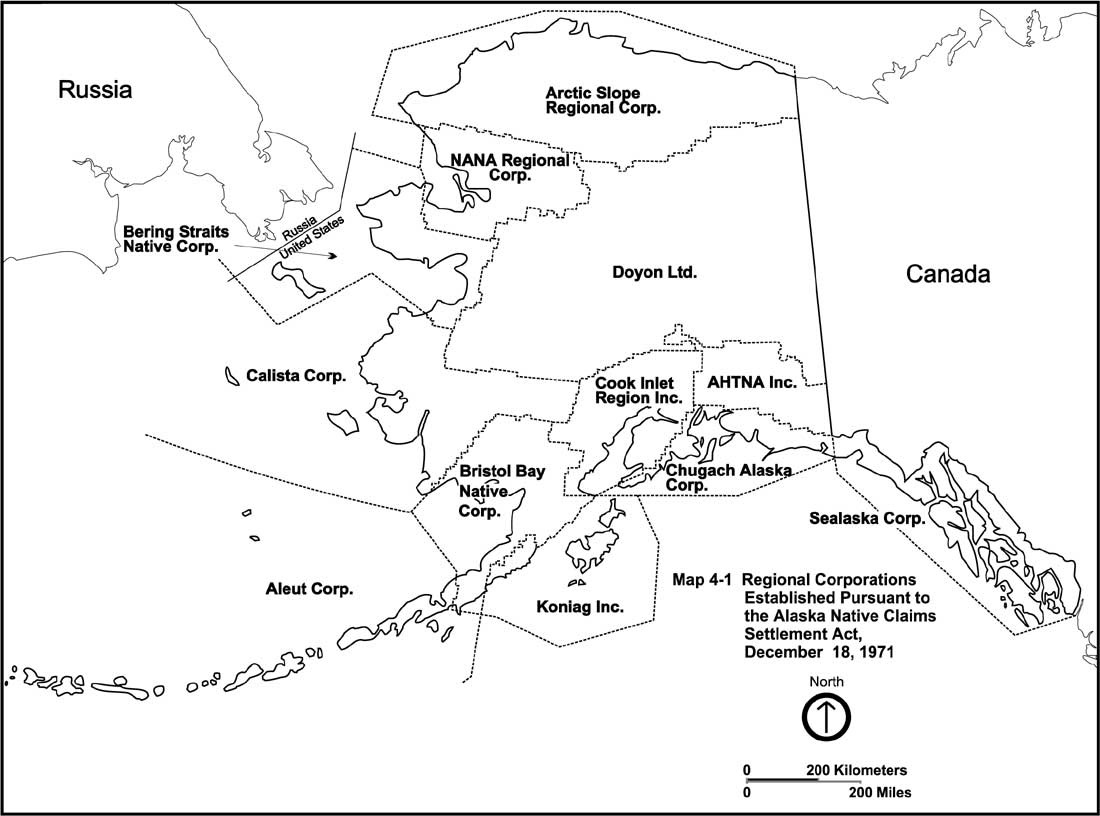

The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act is a treaty in which the United States government granted the legal title to 44 million acres, along with the mineral rights of this territory in Alaska to Native peoples. The 44 million acres that went to Native Alaskans were picked by the Natives over a period of time. 22 million acres were to be picked by the 246 village corporations that were created through the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act and 16 million acres were set aside for certain regional corporations (Anders 1983). The United States government also gave Natives of Alaska $962.5 million (Hales and Goniwiecha, 1986). This $962.5 million was split between the United States federal government and the State of Alaska and was to be paid over eleven years to the Alaska Native Fund (Anders, 1983). The act additionally divided Alaska into twelve geographic regions in correspondence with the twelve Native associations formed prior to the land settlement. Each of these regions were considered regional corporations, so it actively brought Native people into the capitalistic world.

With the money that these geographic regions received, a majority of the money went to villages that were located in each of these regions. This money was primarily used to survey the land for the villages land selection, which was vital to the villages’ futures (Berry, 240). This land selection could either mean disaster for their way of life or the prospect of a positive future. The land selection was so important due to the Natives claim to the minerals in their selected lands. Many of the villages hired biologists and geologist to give an accurate depiction of geographical and mineral information. Natives want to make sure that they were picking valuable pieces of land, so they could further profit off of their selection.

However, as this land claim seemed generous to the Native peoples, it came with a number of areas of conflict. The first was the increased dependency on non-natives. Few Natives were capable of carrying out a number of the responsibilities laid out in the ANCSA, so non-Natives that were professionals in specific fields of Native responsibilities were hired. The next issue came from the competition between Native Corporations. Native Corporations found themselves competing over profitable investments based on their resource endowment and the conflict between renewable resources and resource extraction. A third issue that arose was the social stratification in the native communities. With the ANSCA, a new elite class of Corporate Natives were born. Their high-paying positions socialized these Natives in different was that made them seem less attentive to the concerns and daily conditions of the majority of rural Native Alaskans. This situation of social stratification was only magnified when more rural Native Alaskans moved to urban areas to take advantage of the newly created jobs through the ANSCA (Anders, 1983).

Caption: Depiction of the regions created during the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971

Source: National Parks Service

Anders, Gary. 1983. "The Role of Alaska Native Corporations in the Development of Alaska." Development and Change 14 (4): 555-575. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7660.1983.tb00166.x.

Berry, Mary Clay. 1975. The Alaska Pipeline : The Politics of Oil and Native Land Claims. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Hales, David A., and Mark C. Goniwiecha. 1986. "Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act and National Interest Lands: Some Major Resources." Reference Services Review 14 (1): 35-40. doi:10.1108/eb048925.

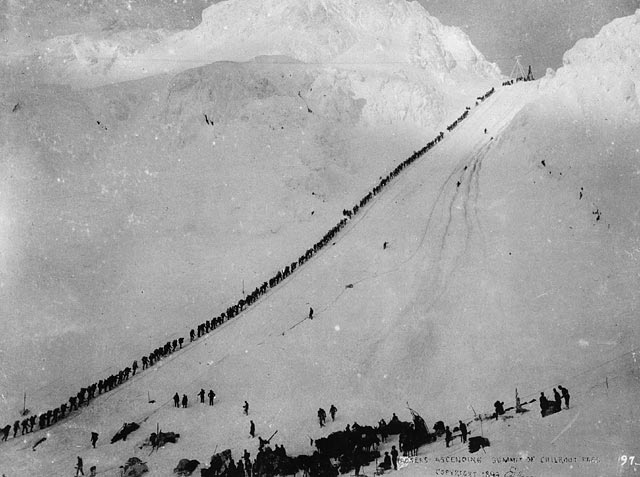

Caption: The Chilkoot Pass in the midst of the Klondike Gold Rush of 1898. Prospectors hike up the frigid pass often making multiple trips to haul all of their gear through the pass.<br>

Source:

Caption: The Chilkoot Pass in the midst of the Klondike Gold Rush of 1898. Prospectors hike up the frigid pass often making multiple trips to haul all of their gear through the pass.<br>

Source: