The majority of the annotations on this page draw from the following critical editions of The War of the Worlds, which will be cited and tagged according to the last name(s) of the editor(s) of that edition:

DANAHAY: Martin A. Danahay. The War of the Worlds. Broadview Press, 2003.

HUGHES AND GEDULD: David Y. Hughes and Harry M. Geduld, eds. A Critical Edition of The War of the Worlds: H. G. Wells’s Scientific Romance, with Introduction and Notes by David Y. Hughes and Harry M. Geduld. Indiana UP, 1993.

MCCONNELL: Frank McConnell, ed. The Time Machine and The War of the Worlds: A Critical Edition. Oxford UP, 1977.

STOVER: Leon Stover. The War of the Worlds: A Critical Text of the 1898 London First Edition, with an Introduction, Illustrations and Appendices. McFarland and Company, Inc, 2001.

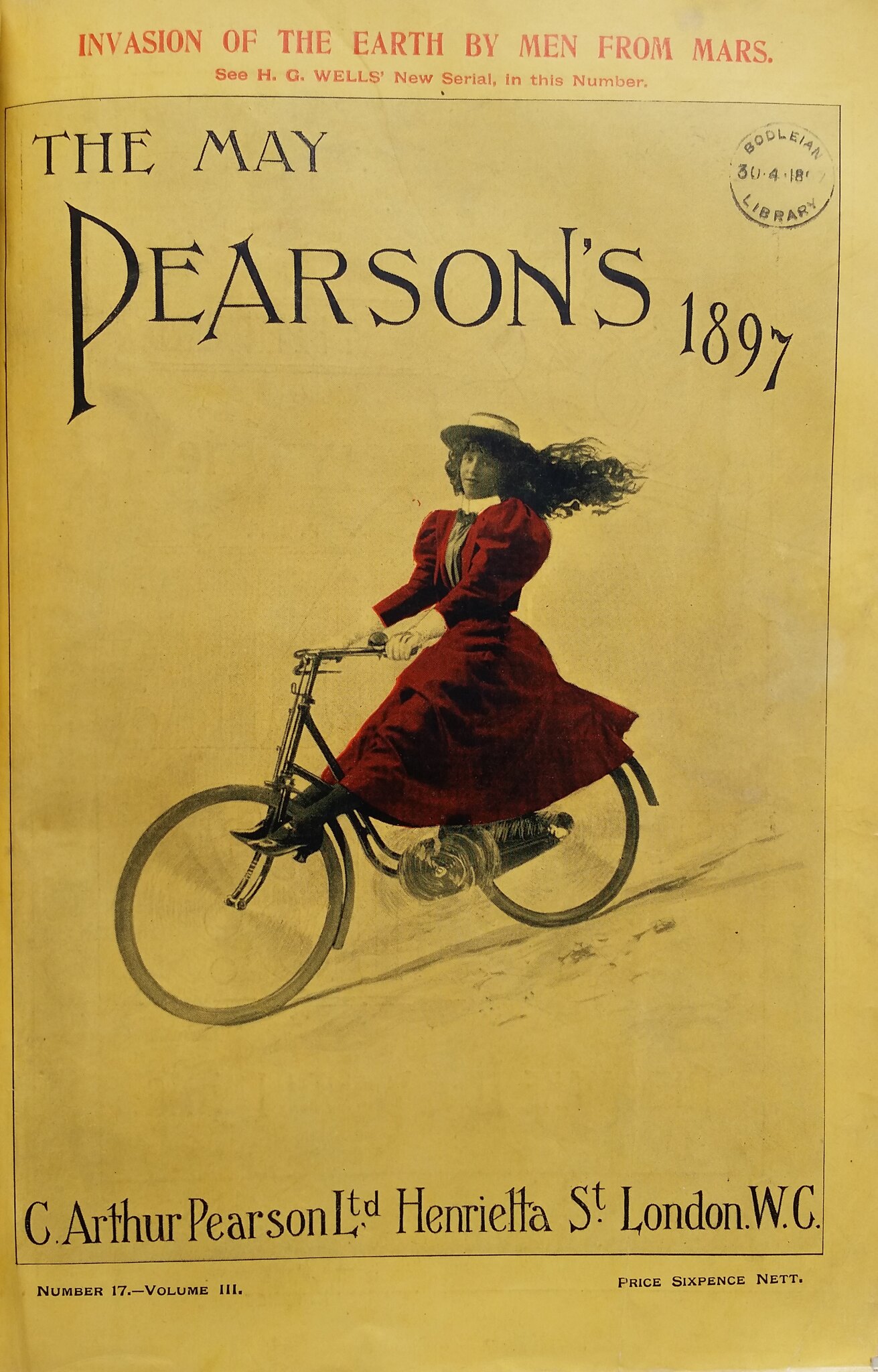

Madeline Gangnes has added additional annotations and resources, especially those that address materials related to Pearson's Magazine and adaptations of the text. They are cited with their source(s) (where applicable) and tagged as GANGNES.