commonweal

GANGNES: In this case, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, "common well-being; esp. the general good, public welfare, prosperity of the community."

commonweal

GANGNES: In this case, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, "common well-being; esp. the general good, public welfare, prosperity of the community."

conducive to digestion and even essential

GANGNES: We now know for a certainty that bacteria are absolutely essential to digestion in human beings and many other organisms. See Sai Manasa Jandhyala, et al, "Role of the Normal Gut Microbiota" (2015).

“Germs.”

GANGNES: The Germ Theory of Disease ("Germ Theory")--the understanding that diseases are caused by microorganisms (bacteria and viruses)--only came into British public consciousness toward the end of the nineteenth century. Prior to the rise of Germ Theory, "Miasma Theory" dominated scientific conceptions of the nature of disease. Gaining a better understanding of how diseases were caused and spread led to reforms in public health and sanitation.

More information:

went up the stairs. I went

GANGNES: The 1898 volume inserts the following paragraph between these two:

"I followed them to my study, and found lying on my writing-table still, with the selenite paper weight upon it, the sheet of work I had left on the afternoon of the opening of the cylinder. For a space I stood reading over my abandoned arguments. It was a paper on the probable development of Moral Ideas with the development of the civilising process; and the last sentence was the opening of a prophecy: 'In about two hundred years,' I had written, 'we may expect——' The sentence ended abruptly. I remembered my inability to fix my mind that morning, scarcely a month gone by, and how I had broken off to get my Daily Chronicle from the newsboy. I remembered how I went down to the garden gate as he came along, and how I had listened to his odd story of 'Men from Mars.'"

Through this revision, Wells reminds the reader that the narrator is a philosophical writer. There is an irony here: in his paper, the narrator speculates on moral development two centuries after what ends up being the arrival of the Martians. Speculating about far-future morality is proven folly in the face of an unforeseen present crisis that leaves human beings struggling to live at all, let alone live according to a certain moral code. There is also an implicit irony to the fact that the Martians are at least two centuries ahead of human beings technologically, and they have their own "moral" codes far different to what the narrator might have expected. See text comparison page.

kindly insipidity

GANGNES: In this case insipidity would be defined as "want of taste or judgement; weakness, folly" (Oxford English Dictionary). The narrator is not altogether pleased with the French operator's comments; France cheers England's "triumph" over the Martians, after having offered no aid during the crisis. Essentially, his "tousand congratulation" are in poor taste considering the circumstances.

Jewess

GANGNES: Another instance of casual anti-Semitic language, though the narrator does not seem to mean it disparagingly, and it is not nearly as offensive as "the Jew" clutching at gold in the narrator's brother's story. The word did not have to be changed (if, indeed, it would have been changed) for the volume because this entire section was cut.

Camden Town

GANGNES: district in north London just southeast of Primrose Hill and northeast of Regent's Park, adjacent to the London Zoo

eked

GANGNES: "to supplement, supply the deficiencies of anything" (Oxford English Dictionary)

XXII.―THE EPILOGUE.

GANGNES: The Epilogue was completely overhauled for the 1898 volume. Firstly, it was split into two parts: Book II, Ch. IX ("Wreckage") and Book II, Ch. X ("Epilogue"). The first five paragraphs of the serial's Epilogue were cut, and eight new paragraphs were written for the beginning of Book II, Ch. IX, the rest of which came from the serial's Epilogue. A few other paragraphs from the serial were cut for the new Epilogue (see below notes).

This rearrangement and supplementation of text has been simplified and/or glossed over in other scholars' accounts of revisions between the Pearson's version and the 1898 volume of the novel. When mentioned at all, it is often said that for the volume, Wells added "The Man on Putney Hill" and a "new Epilogue." Comparison of the text reveals that the reality of the revision was far more complicated, with a fair amount of text preserved from the serial to create the reworked Epilogue. Engaging with these nuanced changes offers insights into not only the editorial process of collecting serialized works for volume publication, but also the degree to which rearranging, tweaking, and supplementing text can affect pacing, characterization, and "message" at the end of a novel. See text comparison page.

tintinnabulations

GANGNES: "a ringing of a bell or bells, bell-ringing; the sound or music so produced" (Oxford English Dictionary)

Crystal Palace

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 228: "a Victorian exhibition center constructed (in 1854 by Sir John Paxton) of glass and iron. It was originally used to showcase materials from the Great Exhibition of 1851. The Palace, which burned in the 1930s, was in Sydenham in southeast London, about eight miles from the city center."

GANGNES: The Crystal Palace was a massive glass structure constructed for the Great Exhibition of 1851. It stood in Hyde Park, London until it was moved to Sydenham Hill in 1852-4, where it remained until it was burned down in 1936. During the Exhibition, it housed exhibits on cultures, animals, and technologies from all over the world.

More information:

would fight no more for ever

GANGNES: Note here that HUGHES AND GEDULD disagree with MCCONNELL's identification of the reference.

From MCCONNELL 289-90: "A last, and very curious, invocation of the sub-theme of colonial warfare and exploitation. In 1877 Chief Joseph of the Nez Percé Indians had surrendered to the United States Army in a noble and widely-reported speech: 'I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed. . . . Hear me, my chiefs, I am tired. My heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands I will fight no more for ever.' Wells, by associating the tragic dignity of Chief Joseph's language with the now-defeated Martian invader, achieves a striking reversal of emotion. For we now understand that it is the Martians, pathetically overspecialized prisoners of their own technology, who are the truly pitiable, foredoomed losers of this war of the worlds, of ecologies, of relationships to Nature."

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 224: MCCONNELL's comment is "farfetched. ... [T]he Nez Perce in Wells's day were unsung, and he would not deal in such an obscure allusion."

More information:

put upon this earth. Here and there they were scattered

GANGNES: In the 1898 volume, a large paragraph is added between these two:

"For so it had come about, as indeed I and many men might have foreseen had not terror and disaster blinded our minds. These germs of disease have taken toll of humanity since the beginning of things—taken toll of our prehuman ancestors since life began here. But by virtue of this natural selection of our kind we have developed resisting power; to no germs do we succumb without a struggle, and to many—those that cause putrefaction in dead matter, for instance—our living frames are altogether immune. But there are no bacteria in Mars, and directly these invaders arrived, directly they drank and fed, our microscopic allies began to work their overthrow. Already when I watched them they were irrevocably doomed, dying and rotting even as they went to and fro. It was inevitable. By the toll of a billion deaths man has bought his birthright of the earth, and it is his against all comers; it would still be his were the Martians ten times as mighty as they are. For neither do men live nor die in vain."

In the serialized text, a similar rumination on microorganisms and their role in the Martians' destruction is positioned, though not phrased the same way, closer to the end of the installment's epilogue. Changing the order of these mental asides by the narrator alters the pacing and reveals background information at different points in the narrative. See text comparison page.

St. Edmund’s Terrace

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 233: "a street in central London, between Regent's Park (on the south) and Primrose Hill (on the north)"

We were the last of men.

GANGNES: Cut from the 1898 volume. See text comparison page.

Baker Street

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 227: "an important thoroughfare in London's West End area. The (fictitious) home of Sherlock Holmes was at 221B Baker Street."

GANGNES: The majority of the Sherlock Holmes stories, like The War of the Worlds, were serialized in a popular general-interest periodical--in this case, The Strand Magazine. Arthur Conan Doyle, who wrote the Holmes stories, was an active fiction writer around the same time as Wells, and they published in some of the same periodicals.

More information:

South Kensington

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 233: "the sector of the west London borough of Kensington due south of Kensington Gardens and Hyde Park. It is the home of many of London's great museums."

Installment 6 of 9 (September 1897)

This installment comprises the text that is roughly comparable to Book I ("The Coming of the Martians"), part of Chapter XV through the beginning of XVII of the 1898 collected edition and subsequent versions.

This is the cover of the September 1897 issue of Pearson's Magazine:

Just after midnight the fifth cylinder fell, green and livid, crushing a house, as I shall presently tell in fuller detail, beside the road between Richmond and Barnes. The fifth cylinder—and there were five more yet to come!

GANGNES: Cut from the 1898 version. Likely the extent to which the break between Chapters XVI and XVII changed the flow of the narrative made this installment ending redundant. It works very effectively in the serial as a suspense-building hint at the next part of the narrative, but is perhaps not necessary in a collected volume. See text comparison page.

six million people

GANGNES: In the Pearson's Chapter XIV, the number of Londoners is written as "five million"; it is correct here, and Chapter XIV was changed in the volume so that both would read "six million."

The Jew

GANGNES: The anti-Semitism embodied in this figure is clear even when "Jew" is changed to "man" in the 1898 volume and subsequent editions (see the text comparison page). As STOVER (111) observes, the caricature of a greedy "eagle-faced man" would have been recognizable to Victorian readers even with the explicit word "Jew" removed.

Vestry

GANGNES: Note that MCCONNELL, HUGHES AND GEDULD, and STOVER do not completely agree on their explanations of this reference.

From MCCONNELL 218: In the Church of England, the Vestry is not just the room in a church where vestments are stored; it is also a committee of parishioners who arrange local matters like street cleaning.

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 214: "Vestry here is not used in its usual ecclesiastical sense but refers to a committee of citizens 'vested' with the task of arranging for such basic local services as health and food inspection and garbage disposal. St. Pancras (then a London borough) is located northwest of the City of London."

From STOVER 161: "A public-health committee of that city district responsible for its garbage removal--a task now beyond its capacity as all public services are overwhelmed."

lowering

GANGNES: according to the Oxford English Dictionary, "to frown, scowl; to look angry or sullen"

Essex towards Harwich

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 229: Essex is "a county of southeast England bordered by Cambridge and Suffolk (on the north), the river Thames (on the south), London (on the southwest), and the North Sea, Middlesex, and Hertford (on the east)."

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 230: Harwich is "a North Sea port in northeast Essex, at the confluence of the rivers Stout and Orwell, about seventy miles northeast of London."

GANGNES: Essex is 32-33 miles east of New Barnet; essentially the same area as Chelmsford (where the narrator's brother's friends live).

fugitives

GANGNES: in this case, someone who is fleeing from danger; see Oxford English Dictionary

Chalk Farm

GANGNES: area of London on the north side of the Thames; north of the British Museum and on the way north to Haverstock Hill, where the narrator's brother goes next

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 228: "In the 1890s [Chalk Farm Station] was a busy station on the London and North-Western Railway (terminus Euston), at the junction of Adelaide Road and Haverstock Hill, immediately north of Primrose Hill in central London."

outhouses

GANGNES: In this case, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, the door to "subsidiary building in the grounds of or adjoining a house, as a barn, shed, etc."

And here I come upon the most obscure of all the problems that centre about the Martians, the riddle of the Black Gas.

GANGNES: The 1898 volume replaces this sentence with "Now at the time we could not understand these things, but later I was to learn the meaning of these ominous kopjes that gathered in the twilight." The fact that Chapter XV is not divided in the volume allows for a smoother transition. See text comparison page.

magnum

GANGNES: "a bottle for wine, spirits, etc., twice the standard size and now usually containing 1½ litres (formerly two quarts); the quantity of liquor held by such a bottle" (Oxford English Dictionary)

I went down Putney High Street

GANGNES: The section beginning here and ending with "...across the pavement" is either removed from the 1898 volume or repurposed and moved until after an additional chapter--"The Man on Putney Hill"--is inserted. There is a lengthier note about "The Man on Putney Hill" at the beginning of Installment 9. See text comparison page.

Apparently the Martian had taken it all on the previous day.

GANGNES: This is a truly terrifying moment if we remember that the Martians do not digest food. They did not take the supplies in the pantry because they wanted them for themselves to consume; they took the supplies because they suspected that a human being was in the house, and by taking the provisions they can starve him out.

touching and examining

GANGNES: The tactile nature of the Martians' hunt for the narrator is a scene of intense tension in adaptations and illustrations of the novel. Byron Haskin’s 1953 film increases the danger posed by the machine's searching tentacle by adding a mechanical "eye" to its end, so that the characters must stay out of sight as well as sitting still.

More information:

catch

GANGNES: In this case, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, "a device for fastening or checking the motion of something, esp. a latch or other mechanism for fastening a door, window, etc."

worried

GANGNES: In this case, according to the Oxford English Dictionary: "to pull or tear at (an object)."

Briareus

From MCCONNELL 259: "in Greek myth, a pre-Olympian giant with fifty heads and a hundred hands."

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 220: "In Greek mythology Briareus was a giant with fifty heads and a hundred hands."

From STOVER 210: "Briareus, in Greek mythology, is a giant with fifty heads and a hundred hands. The Martians' robotic Handling Machines are the multiplex hands of their guiding heads--one giant in their common purpose."

From DANAHAY 156: "in mythology, a monster with a hundred hands"

More information:

The brotherhood of man! To make the best of every child that comes into the world! . . How we have wasted our brothers! . . . . . Oppressors of the poor and needy. . . . The Wine Press of God!

From MCCONNELL 257: "A jumble of Biblical allusions, probably the most important of which is to Isaiah 63:3, an image of apocalypse or the vengeance of God."

From DANAHAY 155: (re just "The Wine Press of God") See Isaiah 63:3.

sex

GANGNES: In this case, the word refers to an organism's sex based on chromosomes (which most Victorians would conflate with gender). The "budding off" makes it clear that Martians do not have sexual intercourse, so any differences in chromosomes (if any) are inconsequential. The Martians have achieved a kind of asexual utopia, where their energies and emotions are not "wasted" on finding a mate. Human beings, with our base impulses and inefficient digestive systems, don't stand a chance against advanced beings who quickly process sustenance, never sleep, and don't have to bother with courtship and breeding.

tear out the hair of the living women they captured, in order to deck themselves with the spoils; nor did they, in my judgment, carry the sporting instinct quite so far as men

GANGNES: These are references to how human beings treat "lower animals"; for example, hunting them for fun, skinning them or cutting off their horns for clothing and jewelry, and so forth. The comparison would be especially appropriate during a time when "big game"/trophy/sport hunting in colonial locales (especially Africa) was popular among British men. A particularly tragic example is the ivory trade, which forms the backdrop of Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness (1899).

More information:

vivisects

GANGNES: Vivisection is "the action of cutting or dissecting some part of a living organism; spec. the action or practice of performing dissection, or other painful experiment, upon living animals as a method of physiological or pathological study" (Oxford English Dictionary).

Since Wells cut this section from the volume, no explicit reference to vivisection remains in a collected edition of the novel. However, the practice is central to Wells's 1896 novel The Island of Doctor Moreau.

More information:

tenth Cylinder

From STOVER 188: (with regard to cutting this section) "Wells may have considered the fact that the narrator's reference to a 'tenth cylinder' is three too many. On the other hand, his miscounting of the seven actual landings would be consistent with his unreliability on so many other points."

The bare idea of this is no doubt horribly repulsive to us, but at the same time I think that we should remember how repulsive our carnivorous habits would seem to an intelligent rabbit.

GANGNES: The text beginning with "I know it is..." and ending with "But I wander from my subject" several paragraphs later was cut from the 1898 volume. See text comparison page.

STOVER argues, "The reason Wells cut this passage from the book version is probably aesthetic. He did not wish to give away too much, if he were to keep with the novel's deepest artistic ambiguity" (188). However, this assessment risks oversimplifying an extensive edit. Apart from "giving away too much"--offering a lot of information that the narrator would not find out until much later and therefore informing the reader of details about the Martians relatively early--this passage can come off as "preachy" or overly philosophical in a way that Wells may have later decided he disliked.

This omitted section tells us a great deal not only about the Martians' grisly study of a live human subject, but also about the narrator's ideologies. Looking back on his first glimpses of the Martians from a later time of safety, the narrator offers a kind of persuasive philosophical essay (he is, by trade, a professional writer of similar essays) on the ethical and moral lessons to be gleaned, from the Martians' behavior, about humans' treatment of other animals.

While the passage may "wander from [the narrator's] subject," it offers an intriguing dissonance between the narrator's terror of being killed by the Martians--to the point where he sacrifices others' lives--and his cool, high-minded defense of their consumption of human beings.

In the end, Wells retains only the first sentence of this passage in the volume to speak very briefly to the narrator's philosophical thoughts on the matter. What we gain in narrative flow and "artistic ambiguity" we may lose in characterization.

So it came about that I and the curate were imprisoned out of the sight of, and yet within sound of, the Martians, and by creeping up to the triangular hole in the broken wall, we could even lie (and to that our courage attained on the second day) peeping through a narrow crack between two masses of plaster at them.

GANGNES: The first six paragraphs of Chapter XIX were cut from the text when it was collected as a volume, and replaced with a similar amount of text at the beginning of what became Book II, Chapter II of the 1898 volume. See text comparison page.

The replacement of this section relates to Wells's reorganization of the narrative toward the end of the novel. Certain devices, such as the foreshadowing in sentences like "The dreadful thing that happened at last between myself and the curate, and how in the end I escaped from that house, I will defer from telling in this chapter," are not as necessary in a volume; in fact, they can disrupt narrative flow. Foreshadowing helps keep a serial reader interested in an installment of a story and interested in buying the next one when it comes out.

Fifth Cylinder

GANGNES: MCCONNELL 240 identifies this as a "contradiction. The fourth start had fallen late Sunday night, north of where the narrator and the curate are hiding..., and the narrator only hears of it later, from his brother. So it is impossible for him to know, at the time, that this is the fifth star; he should think it is the fourth." A case could be made, however, that the narrator is writing this in retrospect, and therefore could be imposing his later knowledge of which cylinder it is onto his impressions at the time.

HUGHES AND GEDULD further complicate the matter by responding to MCCONNELL: "But the first three cylinders fell one after the other late on the nights of Thursday, Friday, and Saturday. Doubtless the narrator simply assumes that the fourth fell 'late Sunday night' and that this one (late Monday night) is the fifth. ... The real trouble is that--far from being unaware of the fourth cylinder--the narrator should be only too well acquainted with it. It fell the previous night, into Bushey Park, which he and the curate have just traversed. But Wells has forgetfully caused the park to contain nothing more remarkable than 'the deer going to and fro under the chestnuts.'"

aperture

GANGNES: In this case, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, "An opening, an open space between portions of solid matter; a gap, cleft, chasm, or hole."

Our situation was so strange and dangerous

GANGNES: A great deal of text here was shifted around and significantly revised for the volume. See text comparison page.

semi-detached villa

From MCCONNELL 238: "a still-common English term for a suburban dwelling house"

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 216: "a fashionable name for a kind of small suburban house--in this case a two-family structure--popularly considered to be a 'better class' of dwelling"

GANGNES: Americans might call this kind of house a high-end "duplex," in that the structure itself is the size of a large house, but there are two "homes" within it, separated by a long dividing wall. Many semi-detached houses have two floors.

Pompeii

From MCCONNELL 236: "the Roman city on the Bay of Naples, completely buried by the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in 79 A.D."

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 216: "The eruption of Mount Vesuvius near Naples on August 24, A.D. 79 buried the towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum under thousands of tons of volcanic ash and lava, killing some 20,000 inhabitants."

From DANAHAY 136: "The Roman city of Pompeii was destroyed by a volcanic eruption in 79 A.D. Archaeologists found citizens of Pompeii who had been overcome by the ash from the eruption preserved where they had fallen."

More information:

matchwood

GANGNES: In this case, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, "very small pieces or splinters of wood."

thirty-six pounds

From MCCONNELL 228: at the time, ~$180

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 215: at least ten times the usual amount

Channel Fleet

GANGNES: "a fleet of the Royal Navy detailed for service in the English Channel. ... In 1909 the Channel Fleet became the 2nd Division of the Home Fleet." (Oxford English Dictionary).

Chipping Ongar

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 228: "a small town in west Essex about sixteen miles north-northeast of London"

GANGNES: Chipping Ongar is to the east and slightly north of Edgware, about two-thirds of the way from Edgware to Chelmsford (relevant to the narrator's brother's journey).

Colchester

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 228: "a town in northeast Sussex, on the river Colne, about seventy miles northeast of central London"

GANGNES: Colchester is near the east coast of England, ~25 miles northeast of Chelmsford.

Blackfriars Bridge. At that the Pool became a scene of mad confusion, fighting and collision, and for some time a multitude of boats and barges jammed in the northern arch of the Tower Bridge

GANGNES: Blackfriars Bridge and Tower Bridge are two large bridges spanning the Thames from north to south in the eastern part of London. Today, the Millennium Bridge (a pedestrian bridge) and Southwark Bridge lie between them, but Southwark Bridge was not opened until 1921, and the Millennium Bridge 2000 (hence the name). These are four of the five Thames bridges overseen today by the London City Corporation. See the City of London site's page on bridges.

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 227: Blackfriars Bridge is "a bridge in central London between Waterloo Bridge and Southwark Bridge. It spans the Thames from Queen Victoria Street (on the north) to Southwark Street (on the south).

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 234: Tower Bridge is "London's most famous bridge. It opens periodically to admit the passage of shipping. It spans the Thames between the Tower of London (on the north) and the district of Bermondsey (on the south)."

mettle

GANGNES: In this instance, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, "a person's spirit; courage, strength of character; vigour, spiritedness, vivacity"

parapets

GANGNES: In this instance, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, "a low wall or barrier, often ornamental, placed at the edge of a platform, balcony, roof, etc. ... to prevent people from falling"

part of Marylebone, and in the Westbourne Park district and St. Pancras, and westward and northward in Kilburn and St. John’s Wood and Hampstead, and eastward in Shoreditch and Highbury and Haggerston and Hoxton, and indeed through all the vastness of London from Ealing to East Ham

GANGNES: As is evident by this point, the entirety of The War of the Worlds is specifically situated in actual locations in and around London. This rapid-fire naming of specific streets and neighborhoods can be overwhelming to readers who are not familiar with London, but to those who are (as many of Wells's readers would be), they underscore that this crisis is happening in a very real location. It also gives the narrative a breathless sense of momentum while maintaining the specificity of war reporting.

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 235: Westbourne Park is "a district in the London borough of Kensington, about two and a half miles from the city center."

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 233: St. Pancras is "a London borough north of the Thames, two miles form the city center. It is the site of Euston and St. Pancras [train] stations, main transit points for northern England and Scotland."

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 230: Kilburn is "a northwest London district between Hampstead (on the north) and Paddington (on the south), about three and a half miles northwest of central London."

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 233: St. John's Wood is "a middle-to-upper-class residential district northwest of Regent's Park, in north London."

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 229: Hampstead is "a hilly northeast London suburb, about five miles from the city center. From its highest point, on Hampstead Heath, it offers a magnificent vista of London."

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 233: Shoreditch is "a working-class district in east London, about a mile from the city center."

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 229: Haggerston is "a tough, working-class district in north London, north of Bethnal Green and east of Shoreditch."

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 230: Hoxton is "a tough, working-class district in north London, between Shoreditch and Haggerston, about two miles northeast of Charing Cross in central London."

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 229: Ealing is "a London borough in the county of Middlesex, some eight miles west of the city center."

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 229: East Ham is a "London district in the county of Essex, about seven miles east of the city center."

Marylebone Road

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 231: "a busy central-London thoroughfare, south of Regent's Park, between Lisson Grove (on the west) and Baker Street (on the east)."

the Strand

GANGNES: The Strand (technically just "Strand") is a road just south of Trafalgar Square (see below) and north of the Thames; it runs along to the east and then becomes Fleet Street (see above). The Strand Magazine, which published the Sherlock Holmes stories, took its name from the fact that its first publishing house was located on Southampton Street, intersecting with Strand.

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 234: The Strand is "an important thoroughfare in central London. It runs parallel with the Thames (a very short distance away) and extends west from the Aldwych to Trafalgar Square. It is the location of fashionable stores, hotels, theatres, and office buildings."

St. James’ Gazette

From MCCONNELL: evening paper published 1880-1905

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 212: "Established in 1880, St. James's Gazette was a pro-Tory paper with features that also appealed to readers with intellectual literary interests."

GANGNES: St. James's Gazette (Pearson's mistakenly leaves off the second "S") was a conservative daily broadsheet. It included social, political, and literary commentary, news, marriage announcements, stock market prices, and advertisements.

Source:

pillars of fire

GANGNES: MCCONNELL is partially incorrect here; his citation is more thorough in that it addresses both the pillar of fire and pillar of smoke, but the appropriate chapter is Exodus 13, not Exodus 15. The most thorough and correct citation here would be a combination of the two--Exodus 13:21-22--which STOVER cites, though inexplicably as a note at the beginning of Chapter XII rather than at the textual reference.

From MCCONNELL 173: "In Exodus 15:21-22, God sends a pillar of fire to guide the Israelites through the Sinai Desert by night, and a pillar of cloud to guide them by day."

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 209: "See Exodus 13:21: 'And the Lord went before them [to guide the Israelites through the Sinai] ... by night in a pillar of fire.'"

From STOVER 114: quotes Exodus 13:21-22, then: "As the Lord guided the Israelites through the Sinai desert, so the Martians lead humanity through a wasteland of suffering. Ahead, leaving the old order behind, is the promise of world unity."

a driver in the Artillery

From MCCONNELL170: "That is, he drove the horse-drawn carriage of the heavy field guns."

GANGNES: As other scholars have pointed out (e.g., HUGHES AND GEDULD 210), the marked difference in the role of the artilleryman in the Pearson's version as compared with the volume constitutes a significant change between the two versions. He is the "man" in the new chapter--"The Man on Putney Hill"--added for the volume, and he is a conduit through which the novel explores how humankind might grapple (or fail to grapple) with such a crisis as the Martian invasion. See Installment 9.

torpor

GANGNES: according to the Oxford English Dictionary, "absence or suspension of motive power, activity, or feeling"

Later I was to learn that this was the case. That with incredible rapidity these bodiless brains, these limbless intelligences, had built up these monstrous structures since their arrival, and, no longer sluggish and inert, were now able to go to and fro, destroying and irresistible.

GANGNES: This section is replaced in the 1898 edition with the following passage after "...rules in his body?":

"I began to compare the things to human machines, to ask myself for the first time in my life how an ironclad or a steam engine would seem to an intelligent lower animal."

This revision is particularly interesting because Wells removed language referring to steam engines and other human technologies in the narrator's description of the fighting machines in the previous chapter (beginning "And this Thing!").

In this site's page on "The Terrible Trades of Sheffield," a connection is drawn between these edits and Wells's opinion of Warwick Goble's illustrations, which were too close to human technologies. In the revision, then, Wells reframes human technologies as part of an analogy; Martian technology is beyond human technology to so extreme a degree as to be incomprehensible to humans.

the potteries

From MCCONNELL 168: "A district in central England, also called the 'Five Towns,' famous for its pottery and china factories. The area was a favorite subject of Wells's friend, the novelist Arnold Bennett (1867-1931)."

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 208: The "five towns" MCCONNELL refers to are Stoke-on-Trent, Hanley, Burslem, Tunstall, and Longton. In 1888 Wells spent three months in the Potteries region.

From DANAHAY 80: "an area of central England with a large number of china factories and their furnaces"

heard midnight pealing out

From DANAHAY 75: church bells ringing

GANGNES: Which is to say, the church bells rang in such a way that indicated the time was midnight.

I’m selling my bit of a pig.

GANGNES: HUGHES AND GEDULD and STOVER both disagree with MCCONNELL about the meaning of this phrase.

From MCCONNELL 159: "The landlord fears he may be selling (not buying) a 'pig in a poke.'"

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 207: "One nineteenth-century slang meaning of 'pig' was goods or property. Hence the sentence might simply mean: 'I'm selling my bit of property.' Another slang meaning of 'pig' was nag, donkey, or moke; while 'bit of' was an adjectival term that could be used variously to express affection for the subject it preceded. ... Another possibility is a real pig, i.e., the landlord is surprised--after asking a pig buyer to pay a pound and drive the pig home himself--to be offered two pounds with a promise moreover to return the pig. According to this, people are simply talking at cross-purposes, and the narrator then explains that he wants a dogcart, not a pig."

From STOVER 98: "The landlord is puzzled by the narrator's haste to pay two pounds for his 'bit of pig' (=his valuable piece of property) coupled with a strong promise to return it."

tea

GANGNES: In this case, the equivalent of dinner or an evening meal (hence it being "six in the evening"). See Oxford English Dictionary: "locally in the U.K. (esp. northern) ... a cooked evening meal"

belligerent

GANGNES: In this case, according to the Oxford English Dictionary: "waging or carrying on regular recognized war; actually engaged in hostilities," which is to say, the narrator is imagining, and is excited about, an epic war between the British and the Martians.

stereotyped formula

GANGNES: In this case, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, "something continued or constantly repeated without change; a stereotyped phrase, formula, etc.; stereotyped diction or usage."

a rapidly fluctuating barometer

GANGNES: This indicates that the weather is volatile and likely heralds an imminent storm. See Oxford English Dictionary on "barometer": "an instrument for determining the weight or pressure of the atmosphere, and hence for judging of probable changes in the weather, ascertaining the height of an ascent, etc" and Encyclopædia Britannica entry.

close

GANGNES: In this usage, according to the Oxford English Dictionary: "of the atmosphere or weather: Like that of a closed up room; confined, stifling, without free circulation."

Sunbury

GANGNES: North and slightly to the east of Upper Halliford, where the narrator and curate are located at this point. Roughly a half-hour walk or less, depending on where in Upper Halliford and where in Sunbury-on-Thames.

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 234: "a town in Middlesex, known fully as Sunbury-on-Thames, thirteen miles west-southwest of London"

parboiled

GANGNES: according to the Oxford English Dictionary, "partially cooked by boiling"

Kingston and Richmond

GANGNES: towns/villages on the banks of the Thames, past Halliford toward central London; Richmond is farther away from Halliford than Kingston

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 230: "Usually called Kingston-on-Thames. A municipal borough in northeast Surrey, about nine miles southwest of central London."

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 233: "a borough of greater London, on the Thames in North Surrey, about eight miles west-southwest of central London"

In my convulsive excitement I took no heed of the artilleryman behind me, and to this day I do not know what became of him. I never set eyes on him again.

GANGNES: This line is cut from the 1898 version because it is no longer true. As HUGHES AND GEDULD (210) and others point out, the artilleryman becomes a major figure in the volume, featured in Chapter 7 of Book II, "The Man on Putney Hill." See text comparison page, the earlier note about the artilleryman on this page, and the note about the artilleryman on the Installment 3 page.

outhouse

GANGNES: In this case, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, the door to "subsidiary building in the grounds of or adjoining a house, as a barn, shed, etc."

these is vallyble

GANGNES: A large collection of orchids would, indeed, have been quite valuable. The craze surrounding "orchid hunting"--the search for rare and beautiful orchids to collect (and/or sell to collectors)--was at its height during the late nineteenth century, to the point where the fad had a name: "orchidelirium." Some varieties would fetch extremely high prices, and wealthy Victorians sank excessive amounts of money into their collections.

Sources and more information:

photographically distinct

GANGNES: See earlier note in this installment from STOVER on "much as the parabolic mirror of a lighthouse projects a beam of light." As MCCONNELL (182) notes in Installment 4: "The first portable camera, the Kodak, had been patented by George Eastman in 1888. Wells himself was an ardent amateur photographer."

Even before the portable camera and the beginnings of amateur photography, the prevalence of photojournalism would have made most readers familiar with, and likely interested in, photography. References to cameras and photography, especially in relation to the heat ray, are prevalent throughout the novel.

More information:

the mounted policeman came galloping through the confusion with his hands clasped over his head and screaming

GANGNES: This is the policeman who is depicted running from the Heat Ray in both of Cosmo Rowe's illustrations (the Installment 1 header image and the Installment 2 frontispiece).

much as the parabolic mirror of a lighthouse projects a beam of light

From STOVER 81: "The Heat-Ray is often taken as a prophecy of beam-focused lasers, but this is to miss the photographic metaphor Wells uses: 'the camera that fired the Heat-Ray,' 'the camera-like generator of the Heat-Ray.' The Martians' rayguns are in fact cameras in reverse, emitting light not receiving it, and they are in fact mounted on tripods as were the heavy old cameras of the day. What they see they zap. More, the photo-journalistic realism of the invasion recounted by the narrator recalls that of Roger Fenton, whose coverage of the Crimean War in 1855 is the first instance of a war photographer on the scene of action. His pictures were accompanied by sensational stories done by the famed William Howard Russell of the London Times, the first war correspondent in the modern sense. The narrator's account is modeled after both precedents, visually and journalistically."

GANGNES: Stover here gestures (though not by name) to MCCONNELL (145), whose note is quoted by HUGHES AND GEDULD in their edition. MCCONNELL'S note reads: "Though the details of the heat-ray are vague, they do anticipate in some remarkable ways the development of the laser beam in the 1950s."

That said, MCCONNELL and others rightly point to one of the numerous instances in which Wells's descriptions of technologies and events appear prescient. Indeed, many of the Martian technologies seem to anticipate military tech developed for use in the First and Second World Wars. For an analysis of The War of the Worlds and its early illustrations as they relate to early twentieth-century warfare, see Gangnes, "Wars of the Worlds: H.G. Wells’s Ekphrastic Style in Word and Image" in Art and Science in Word and Image: Exploration and Discovery (Brill, 2019), pp. 100-114.

Knap Hill

GANGNES: Changed to "Knaphill" in the 1898 edition and subsequent versions.

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 204 and 230: Knaphill is ~3 miles due west from Horsell Common. The distances might seem exaggerated to today's readers, but they are presented from a pedestrian's perspective.

SUMMARY

GANGNES: Summaries like these are common in serialized fiction, as they are in comics and in television series--a kind of "previously on" bit of information. This not only reminds readers of what happened in the previous installment (which in this case would have been released a month prior), but also allows new readers to jump in at a later issue if they missed out. This was especially important in cases where an issue of a popular magazine or newspaper might have been sold out.

Gorgon circlet of tentacles

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 203: "Gorgon" is an allusion to monsters from Greek myths "whose hair was a tangle of writing snakes." Humans were irresistibly tempted to look at them, but doing so would turn the viewer to stone.

GANGNES: See Medusa as an example.

“Extra-terrestrial”

GANGNES: This term was relatively new when Wells wrote the novel; it first emerged in the mid-nineteenth century and was generally used in scientific journals.

Source:

telegraph the news

GANGNES: The kind of electrical telegraphy with which Wells's readers would have been familiar began development in the early-to-mid nineteenth century and was commonly used by the end of the Victorian period.

More information:

People in these latter times scarcely realise the abundance and enterprise of our nineteenth century papers.

GANGNES: The narrator's comment here underscores this novel's preoccupation with the Victorian press. The style of the narration evokes something of war journalism from this period, and the unreliability and mercenary practices of newspapers are a theme throughout the novel. Wells is not exaggerating; the Victorian period has been called the "Golden Age" of the British periodical because of the staggering number and quality of newspapers, journals, and magazines published during the time.

More information:

I remember how jubilant Markham was at securing a new photograph of the planet for the illustrated paper he edited in those days.

GANGNES: It is not clear whether "Markham" is supposed to refer to a real editor of a specific newspaper. W. O. Markham edited the British Medical Journal, but that publication was not an illustrated paper. It is highly likely that "Markham" is a fictional character who is an acquaintance of the narrator.

Source:

Punch

GANGNES: Punch (1841-2002) was a weekly satirical magazine that was first marketed toward the Victorian middle class. It included text, cartoons and illustrations, and other visual features. It was characterized by a "whimsical mode of comedy that focused on the trials and aspirations of the still emergent middle classes."

Source:

More information:

the chances against anything man-like on Mars are a million to one, he said

GANGNES: A variation on this line is used as the first sung lines in track 1 ("The Eve of the War") of Jeff Wayne's 1978 musical adaptation of The War of the Worlds (LP only; not originally performed live as a play). In the musical, the line is altered to "The chances of anything coming from Mars are a million to one, he said." In the novel, Ogilvy is telling the narrator that there may well be life on Mars, but it is not likely to be "man-like," i.e., intelligent and capable of communicating in the way humans communicate. The musical's altered line instead has Ogilvy opine that regardless of what kind of life might be on Mars, the odds that Martians would come to Earth are very low.

The musical incorporates narration adapted from the novel, instrumental music, vocals, and "plot" additions. The LP set was sold with an accompanying illustrated booklet related to the novel's plot. The musical has recently been updated as "The New Generation." Live performances of the musical with accompanying stage effects tour the United Kingdom.

More information:

Ottershaw

GANGNES: village to the north of Woking but south of Chertsey

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 232: "A small village about two miles north-northwest of Woking, Surrey, and about three miles from the narrator's home in Maybury. It is the location of Ogilvy's observatory."

Warwick Goble (1862-1948)

GANGNES: Warwick Goble (1862-1943) was a Victorian and early-twentieth-century periodical and book illustrator. His watercolor book illustrations have strong Japanese and Chinese influences and themes. Simon Houfe refers to Goble as a "brilliant watercolour painter of the 1900s and 1920s" and writes that Goble's "filmy translucent watercolours, with their subtle tints and Japanese compositions ... are unique in British illustration, but are not noticed by the collectors of [Arthur] Rackham and [Edmund] Dulac" (210).

In his dictionary entry, Houfe only acknowledges Goble's early relationship with periodicals in his role as a staff illustrator for the Pall Mall Gazette and the Westminster Gazette; Pearson's Magazine is not mentioned, despite the fact that Goble illustrated not only The War of the Worlds, but also Arthur Conan Doyle's Tales of the High Seas (short series) and other pieces in 1897. He provided illustrations for volumes of two other major pieces of late-Victorian serialized fiction: Robert Louis Stevenson's Treasure Island and Kidnapped.

Biographical sources:

Nature

From MCCONNELL 126: Nature is a scientific journal first edited by Sir Norman Lockyer, who was one of Wells's teachers at the Normal School of Science.

From STOVER 57: This is a reference to the article "A strange Light on Mars," which was published in Nature in 1894.

GANGNES: This is one of the many instances where Wells establishes the novel within a framework of real scientific discoveries and historical events. These connections enhance the realism and journalistic quality of the narrative.

More information:

Perrotin, of the Nice Observatory

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 199: Nice Observatory was "France's most important nineteenth-century observatory." It was constructed in 1880 on Mt. Gros, northeast of Nice. It used a 30" refracting telescope.

From MCCONNELL 126: Henri Joseph Anastase Perrotin (1845-1904) was a French astronomer who worked at the Nice Observatory 1880-1904.

GANGNES: The 1898 edition adds a reference to Lick Observatory (in California), which the narrator says noticed the light before Perrotin did.

More information:

Schiaparelli

From MCCONNELL 126: Giovanni Virginio Schiaparelli (1835-1910) was an Italian astronomer who claimed to have discovered "canals" on Mars. Schiaparelli called them canali ("channels" in Italian) but the (mis)translation of the word in to English caused speculation that the canali might have been made by intelligent life.

From STOVER 57: Schiaparelli mapped Mars during the opposition of 1877 and provided names for some surface features still used today.

More information:

Tasmanians

From MCCONNELL 125: In the eighteenth century, England drove native Tasmanians from their land in order to turn Tasmania into a prison colony.

From STOVER 55-6: "The racially Australoid natives of Tasmania survived until 1876 in a state of upper paleolithic culture. To the island's Dutch and later British colonists, they were so many subhumans hunted down for dog meat."

More information:

inferior races

GANGNES: "Inferior" as it is used here reflects Victorian conceptions of racial hierarchies. There are, of course, many, many scholarly works on this subject, but here are a few good places to start:

vanished bison and the dodo

From MCCONNELL 125 and 151: The dodo was a large, flightless bird from Mauritius that was hunted into extinction by the seventeenth century. North American bison were also thought to be on the verge of extinction during this time. This is the first of two comparisons between the extinction of the dodo and the potential extinction of humans by the Martians; the second is in Chapter VII.

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 205: "Later, the very idea of such a bird [as the dodo] was ridiculed ... until skeletal remains came to light in 1863 and 1889."

More information:

idea of life upon them as impossible or improbable

From DANAHAY 41: Reference to a Victorian debate regarding the existence of intelligent life on Mars. See Wells's article "Intelligence on Mars" in the Saturday Review 8 (April 4, 1896), p. 345-46.

More information:

a man with a microscope might scrutinise the transient creatures that swarm and multiply in a drop of water

From DANAHAY 41: Wells was interested in the microscope to the point where he visited a microscope factory for his article "Through a Microscope."

More information:

No one would have believed in the last years of the nineteenth century

GANGNES: Adaptations of The War of the Worlds have tended to modify their settings to match those of their main audience. To aid in establishing their time periods and locations, they open with a prologue that is similar to this one, but with several details changed to suit the adaptation.

The 1938 RADIO DRAMA (Orson Welles, Mercury Theatre on the Air)) begins: "We know now that in the early years of the twentieth century this world was being watched closely by intelligences greater than man's and yet as mortal as his own. We know now that as human beings busied themselves about their various concerns they were scrutinized and studied, perhaps almost as narrowly as a man with a microscope might scrutinize the transient creatures that swarm and multiply in a drop of water. With infinite complacence people went to and fro over the earth about their little affairs, serene in the assurance of their dominion over this small spinning fragment of solar driftwood which by chance or design man has inherited out of the dark mystery of Time and Space. Yet across an immense ethereal gulf, minds that to our minds as ours are to the beasts in the jungle, intellects vast, cool and unsympathetic, regarded this earth with envious eyes and slowly and surely drew their plans against us. In the thirty-ninth year of the twentieth century came the great disillusionment."

The 1953 FILM ADAPTATION (Byron Haskin)) includes a bit of narration before the title that briefly discusses war technology from WWI and WWII, then begins: "No one would have believed, in the middle of the twentieth century, human affairs were being closely watched by a greater intelligence. Yet, across the gulf of space, on the planet Mars, intellects vast and unsympathetic regarded our Earth enviously, slowly and surely drawing their plans against us."

The 2005 FILM ADAPTATION (Steven Spielberg)) begins: "No one would have believed in the early years of the twenty-first century, that our world was being watched by intelligences greater than our own. That as men busied themselves about their various concerns, they observed and studied. Like the way a man with a microscope might scrutinize the creatures that swarm and multiply in a drop of water. With infinite complacency men went to and fro about the globe, confident of our empire over this world. Yet, across the gulf of space, intellects, vast and cool and unsympathetic regarded our plant with envious eyes. And slowly and surely, drew their plans against us."

Perhaps most interestingly, the opening lines were modified to fit a fictional setting: the DC Comics universe. The DC "Elseworlds" comic "SUPERMAN: WAR OF THE WORLDS" (1988) accommodates the existence of Krypton in this way: "No one would have believed, in the early decades of the twentieth century, that the Earth was being watched keenly and closely across the gulf of space by intelligences greater than man's and yet as mortal as his own. One such older world was Mars, where minds that are to our mind as ours are to the beasts--intellects vast and cool and unsympathetic--regarded Earth with envious eyes, and slowly and surely drew their plans against us. Another such world, unknown alike to our earth and to the red planet... was the doomed sphere called Krypton." The narration goes on to link the fates of Earth, Mars, and Krypton to establish their similarities and draw them together under the Elseworlds Martian invasion.

I think that we should remember how repulsive our carnivorous habits would seem to an intelligent rabbit.

GANGNES: Passages such as these garnered praise for the novel in late-Victorian vegetarian publications such as The Herald of the Golden Age (1896-1918) and The Vegetarian Magazine (1890-1909).

More information:

Harrow Road

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 229: "a main thoroughfare of northwest London, north of Hammersmith and south of Willesden"

London veiled in her robes of smoke

GANGNES: The "robes of smoke" here refers to the "London fog" (also known as "pea soup fog," "black fog," and "killer fog"). This greasy, yellowish fog that hung around London in the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries was a byproduct of coal burning. It caused respiratory problems and other illnesses for London residents, especially factory workers. Here, then, Wells offers a vision of a London whose pollution has, perhaps paradoxically, been temporarily swept away by the Martians' own Black Smoke, which has brought London's industry to a standstill.

More information:

Installment 9 of 9 (December 1897)

This installment comprises the text that is roughly comparable to Book II, Chapter VIII ("Dead London") through Chapter X ("The Epilogue") of the 1898 collected edition and subsequent versions. "The Man on Putney Hill"--Book II, Chapter VII of the volume--did not appear in the Pearson's version.

This is the cover of the December 1897 issue of Pearson's Magazine: the 1897 Double Christmas Number:

XXI.―AFTER THE FIFTEEN DAYS (continued).

GANGNES: For the 1898 volume, Wells inserted a new chapter--"The Man on Putney Hill"--just before this point in the text. This chapter features a reunion between the narrator and the artilleryman he met in Woking in Installment 3. In this new chapter, the artilleryman shares his grandiose plans for a new human civilization that would be rebuilt in the water mains beneath London, so that even when the Martians take over, Britons can preserve their culture and thrive there until they are ready to rise up against the Martians. It soon becomes clear to the narrator that the artilleryman has gone mad: the "gulf between his dreams and his powers" is insurmountable. See the 1898 version of the text in facsimile and the Project Gutenberg transcription.

The further I penetrated into London

GANGNES: In addition to the new chapter ("The Man on Putney Hill"), five paragraphs of text were added here in the 1898 volume as the beginning of a new chapter (Book II, Ch. VIII) called "Dead London." See text comparison page. The effect of these additions is that the narrator's experience wandering through an empty London is drawn out and given more narrative room to breathe; in the Pearson's version the narrator encounters the dying Martians much more quickly after his arrival in London.

Somehow I felt that this was not the end.

GANGNES: This line and "That, at any rate, would be completion." (below) were cut from the 1898 volume. Perhaps Wells decided that less of the narrator's internal commentary on his feelings would be more effective. See text comparison page.

Ulla, ulla, ulla, ulla

From STOVER 237: "The 'ulla, ulla' of the last of [the Martians] echoes the Irish Gol, or Ullaloo, a lamentation over the dead. It has classical references in Virgil (Magnoque ululante tumulta) and in Ovid (Ululatibus omne / Implevere nemus), as in the title of E.A. Poe's Ballad 'Ulalume'."

Exhibition Road

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 229: "a spacious thoroughfare in South Kensington, London. Location of the Imperial College of Science, formerly the Normal School of Science (part of the University of London), where Wells studied under Thomas Henry Huxley."

the Serpentine

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 233: "an artificial lake in Kensington Gardens, used for boating"

lying in state, and in its black shroud

GANGNES: To "lie in state" is "the tradition in which the body of a dead official is placed in a state building, either outside or inside a coffin, to allow the public to pay their respects" (Wikipedia). The "black shroud" here refers metaphorically to a burial shroud or a shroud worn by mourners. Here, then, Wells compares the entire city of London and its inhabitants as corpses, and the black smoke (and resulting black dust) as its burial covering.

thought of the poisons in the chemists’ shops, of the liquors the wine merchants stored

GANGNES: These are potential ways to kill oneself and join the rest of London, the narrator considers.

two sodden creatures of despair

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 223: "The drunken man who is black as a sweep and the dead woman with the magnum of champagne. Wells added the statement that she is dead in revising the serial and evidently forgot to drop the mention of her here."

Marble Arch

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 231: "a triumphal stone arch (designed in 1828 by John Nash) in central London, at the northeast corner of Hyde Park"

putrescent

From MCCONNELL 286: "growing rotten or decayed"

From DANAHAY 179: rotting

Samson

From MCCONNELL 286: "The incredibly strong, unruly hero of Jewish folklore whose exploits are celebrated in Judges 13:1-16:31. Taken prisoner by the Philistines, he destroyed himself and them by pulling down the walls of their palace."

overwhelmed in its overthrow

GANGNES: Lost its balance or similar and fell.

Zoological Gardens

GANGNES: Now better known as the London Zoo. The Zoological Society of London established the Zoological Gardens in 1828. For excerpts from primary and secondary accounts, see Lee Jackson, "Victorian London - Entertainment and Recreation - Zoo's and Menageries - London Zoo / Zoological Gardens."

Regent’s Canal

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 232: "one of London's key commercial waterways. It begins at the Commercial Docks, Limehouse (east London), runs north to Victoria Park, traverses much of north London, and then links up with the Paddington Canal, which belongs to a network of canals that extend as far north as Liverpool."

black. Night

GANGNES: In the 1898 volume, the following line is added between these two sentences: "All about me the red weed clambered among the ruins, writing to get above me in the dimness." The addition perhaps adds a sense of being lost in an alien landscape rather than a familiar city; the Martians and their flora have not just destroyed London; they have taken over it. See text comparison page.

The windows in the white houses were like the eye-sockets of skulls.

GANGNES: In his illustrations for the 1906 limited-edition Belgian volume, Henrique Alvim Corrêa sometimes takes a fantastical/magic-realist approach to his depictions, literalizing metaphors and making the mundane strange. In this case, Corrêa literally draws the narrator's conception of London's buildings resembling skulls:

temerity

From DANAHAY 180: recklessness

Albert Road

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 227: "a large thoroughfare north of Regent's Park in central London. Also known as Prince Albert Road."

redoubt

From MCCONNELL 288: fortification

From DANAHAY 181: "a fort put up before a battle to protect troops and artillery"

putrefactive

From MCCONNELL 288: "causing decay or rottenness"

destruction of Sennacherib

From MCCONNELL 289: "'The Destruction of Sennacherib' is the title of one of the most famous poems of Lord Byron (1788-1824). In II Kings: 19 it is related how the Assyrian King Sennacherib brought a great army to war against the Israelites; but, thanks to the prayers of the Israelites, the Lord killed Sennacherib's whole army in a single night. The legend has an obvious relevance to the sudden, total, and unhoped-for obliteration of the Martian invaders."

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 224: "In a single night, in answer to the prayers of the Israelites, God destroyed the Assyrian army led by King Sennacherib (II Kings 19:35-37). This is the subject of Byron's celebrated poem 'the Destruction of Sennacherib'."

From DANAHAY 182: "reference to II Kings: 19 in which an entire army is wiped out by God in one night"

below me. Then at the sound

GANGNES: The 1898 volume inserts a new sentence between these two: "Across the pit on its farther lip, flat and vast and strange, lay the great flying machine with which they had been experimenting upon our denser atmosphere when decay and death arrested them. Death had come not a day too soon." See text comparison page. This revelation raises the stakes in the volume; the serial mentions the Martians' flying machines but does not emphasize the danger posed by them, but the volume stresses that the Martians were improving their flying technology so that they could travel farther across Britain and beyond.

enhaloed

From DANAHAY 182: "the birds form circular patterns like a halo"

Albert Terrace

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 227: "a street linking Regent's Park Road and Albert Road, north of Regent's Park in central London"

There is a round store place for wines by the Chalk Farm Station, and vast railway yards, marked once with a graining of black rails, but red lined now with the quick rusting of a fortnight’s disuse.

GANGNES: This sentence is cut from the 1898 volume and a paragraph break is added. See text comparison page.

Langham Hotel

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 230: "a large, modern (in the 1890s) hotel on Portland Place, in central London, between Marylebone Road and Langham Place"

Albert Hall

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 227: short for The Royal Albert Hall; "a huge enclosed amphitheater in the Italian Renaissance style in South Kensington, London. It was constructed in 1867-71, mainly as a concert hall and is still regularly used for that purpose."

Imperial Institute

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 230: "on Exhibition Road, South Kensington, London. It was opened in 1893 as an exhibition center displaying raw materials and manufactured products that represented the commercial, industrial, and agricultural progress of the British Empire."

Brompton Road

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 227: "a thoroughfare in South Kensington (West London), linking Fulham Road with Knightsbridge"

St. Paul’s

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 233: "Sir Christopher Wren's great cathedral. In London, east of Ludgate Hill, one-eighth of a mile north of the Thames at Blackfriars."

GANGNES: St. Paul's Cathedral is a massive cathedral that traces its origins to the year 604. It lies in the Blackfriars region of London, near the London Stock Exchange, and is tall enough that it would have been visible to the narrator in most parts of the city.

More information:

St. Paul's Cathedral in the late nineteenth century:

Such narratives we must have first in abundance, and afterwards the history may be written.

GANGNES: The narrator here is commenting on the process of historical documentation: historians must gather personal narratives (like his and his brother's) together and synthesize them into "official" records of history. The narrator simultaneously downplays the importance of his account and asserts its role in the creation of historical records.

It speaks eloquently for the lesson that humanity had learned that no attack was made on our stricken Empire during the months of reconstruction

GANGNES: Which is to say, in spite of the weakened state of Britain during the Martian invasion and the rebuilding period, no other country took advantage of this weakness and attacked Britain or its colonies. The narrator takes heart about the human spirit from this, despite the fact that in the same paragraph he mentions cannibalism, and we must remember what he, himself, did to the curate.

Nom de Dieu!

GANGNES: French, "Name of God!"

Vive l’Angleterre!

GANGNES: French, "Long live England!"

special constable

GANGNES: "Special constables" in the Victorian period were private citizens who were appointed or volunteered to help the official police keep the peace in times of crisis. The "white badge" (below) likely refers to the white armbands issued to special constables in the nineteenth century. "Staff" may indicate their truncheons, or the narrator was given another kind of wooden weapon.

More information:

hussars

From DANAHAY 187: "light cavalry, named after the fifteenth-century Hungarian units on which they were modeled"

The door had been forced

GANGNES: Someone had broken in while the narrator was gone.

I dashed out and caught her in my arms.

GANGNES: STOVER (248) incorrectly comments on this line as if it were the ending of the serialized version of the text:

"All critics think this is a weak ending, and ending it was in the serial version of 1897. The Epilogue is new to the book but it, too, strikes the very same note."

This is likely due to some confusion over the fact that an Epilogue was "new to the book"; Wells wrote a new Epilogue for the 1898 volume, for which he retained and rearranged portions of the serialized text, including this scene with the narrator's cousin and wife.

The asterisk inserted here indicates a "hard break" (paragraph break of several lines) in the serialized text, but it is not, as Stover calls it, the novel's ending. Rather, it is simply a pause at the conclusion of the narrator's journey before he reflects on his telling of it, and the outcome and aftereffects of the Martian invasion.

Carver

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 225: This name has not been traced to any "real" person.

At the very base of the vegetable kingdom

GANGNES: The following two paragraphs are cut from the 1898 volume, likely because a similar discussion of microorganisms appears in a different place in the revision. See text comparison page.

That they did not bury any of their dead, and the reckless slaughter they perpetrated, point also to an entire ignorance of the putrefactive process.

GANGNES: The hypothesis here is that the Martians do not bury their dead because the dead do not decompose on their planet, or at least do not decompose in a way that risks making others ill.

three lines in the green

From MCCONNELL 297: "A contradiction. In Book I, Chapter Fifteen, the black smoke is said to produce unusual lines in the blue of the spectrum."

GANGNES: This contradiction appears in the volume because of an added passage in Chapter XV. See note in Installment 6.

possible that it combines with argon

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 225: "This contradicts the earlier statement that the Black Smoke contained 'an unknown element giving a group of four lines in the blue spectrum'. ... Actually, argon, as an inert gas, cannot combine with another element to form a compound."

GANGNES: The "blue spectrum" line is not in the serial. See Installment 6 note. HUGHES AND GEDULD (225) speculate that this kind of "carelessness in this final chapter probably reflects Wells's changing intentions regarding its publication." These "changing intentions" had much to do with Heinemann's insistence on the book being longer (HUGHES AND GEDULD 5-6).

It has often been asked

GANGNES: The following two paragraphs were cut from the 1898 volume. They are substituted in a different part of the ending with a shorter comment about the Martians' flying machines inserted farther up. See note above and text comparison page. In the revision process, the flying machines become a point of frightening calamity avoided rather than a scientific discussion.

a score or so of miles

GANGNES: A "score" is 20 miles, so roughly 20-40 miles.

in conjunction

From MCCONNELL 298: "At conjunction, the Earth and Mars are on opposite sides of the Sun."

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 225: "Mars and Earth are in (superior) conjunction, and farthest from each other, when they are lined up with the sun between them; they are in opposition, and closest to each other, when they are lined up with Earth between Mars and the sun."

From DANAHAY 189: "It is far away from earth, but will be 'in opposition' again."

Lessing

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 225: This name has not been traced to any "real" person.

sinuous marking

From HUGHES AND GEDULD 225: "These sinuous markings are evidently signals. The first occurs on Venus and signals Mars that the Martian invasion of Venus is under way, and the response, occurring on Mars, appears immediately after ('dark' presumably because the signal makes a dark mark on a photographic plate)."

The photographs were reproduced

GANGNES: This sentence was cut from the 1898 volume; we lose this referencing back to the Nature article. See text comparison page.

Knowledge

GANGNES: Knowledge: An Illustrated Magazine of Science, Plainly Worded -- Exactly Described (1881-1918) was founded as a weekly periodical with three-column pages by astronomer Richard Anthony Proctor in an effort to make scientific research more accessible. Advertisements allowed Knowledge to undercut the sales of Nature (see next note and Installment 1). It became a monthly periodical in 1885 and, under the editorship of Arthur Cowper, began to introduce reproductions of astronomical photographs, which allowed for the popular distribution of pictures of the stars. This structure of Knowledge at the time when Wells was writing The War of the Worlds is consistent with the idea that the journal might have published photographs of Mars and Venus.

Source:

corresponding column of Nature

GANGNES: This is a reference to the real article in Nature that was mentioned in Installment 1 ("A Strange Light on Mars").

sidereal

From DANAHAY 190: "having to do with the stars"

gibber

From DANAHAY 191: "to speak rapidly, inarticulately, and often foolishly"

the mockery of life in a galvanised body

GANGNES: Possibly a reference to Mary Shelley's novel Frankenstein; Or, the Modern Prometheus (1818), or at least to the theories about using electricity to reanimate dead flesh that inspired her story. See Sharon Ruston, "The Science of Life and Death in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein" on the British Library's website.

the swift tragedy that had burst upon the world had deranged his mind

GANGNES: The narrator believes the curate to be suffering from what we would now call Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Victorians might have referred to this condition as "male hysteria" in the curate's case; soon it would be called "Shell Shock" due to the PTSD experienced by soldiers during the First World War.

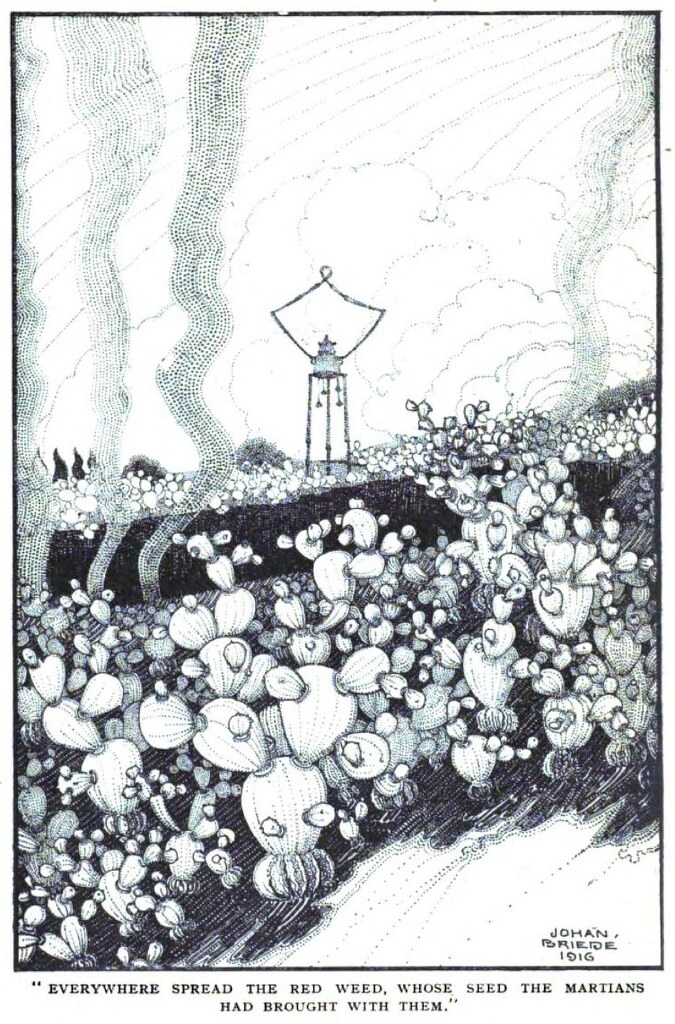

its cactus-like branches

GANGNES: Illustrations of the Red Weed vary significantly across illustrations and adaptations of The War of the Worlds. In many cases, the weed resembles a creeping vine or red kelp. Only one of the novel's major illustrators, Johan Briedé, took the "cactus-like" quality of the plants to heart. Briedé's illustrations were published in The Strand Magazine in 1920 with an introduction from Wells himself.

More information:

Installment 8 of 9 (November 1897)

This installment comprises the text that is roughly comparable to Book II, Chapter II ("What We Saw from the Ruined House") through Chapter VI ("The Work of Fifteen Days") of the 1898 collected edition and subsequent versions.

This is the cover of the November 1897 issue of Pearson's Magazine:

these wretched creatures

GANGNES: Which is to say, the human being captured by the Martians.

tympanic surface

From MCCONNELL 244: "Like the tympanum, the vibrating membrane of the middle ear."

From DANAHAY 143: "A tympan is a drum, so the Martian skin here is like a drum."

The greater part of the structure is the brain, sending enormous nerves to the eyes, ear and tentacles.

From DANAHAY 144: "The Martians are all brain, in keeping with Wells's theory that the bodies of 'advanced' creatures would atrophy through disuse."

pipette

From DANAHAY 144: "a small glass tube used by chemists to move liquid from one area to another"

birds used in pigeon shooting, theirs was indisputably a fortunate one. And the aimless collecting spirit which encourages the systematic impalement of insects by children

GANGNES: Live pigeon shooting was at peak popularity in late-1800s Britain. It involved rounding up live pigeons and releasing them in such a way that participants could shoot them with rifles mid-flight. Clay pigeon shooting was introduced in 1880 as a more controlled, convenient, and humane sport.

The "systematic impalement of insects" refers to butterfly collecting and other sorts of insect collecting--a fad that was extremely popular during the Victorian period (it features in George Eliot's novel Middlemarch (1871-2)). Insects were displayed to their best advantage by driving a pin through their bodies to stick them into display boxes.

More information:

healthy or unhealthy livers

From DANAHAY 145: "Wells himself suffered from liver problems."

silicious

From MCCONNELL 245: "growing in silica-rich soil, crystalline"

From DANAHAY 145: "crystalline, made of silica or sand"

would have crushed them

GANGNES: The following sentence is added here to the 1898 volume: "And while I am engaged in this description, I may add in this place certain further details which, although they were not all evident to us at the time, will enable the reader who is unacquainted with them to form a clearer picture of these offensive creatures." Wells makes a clearer distinction in the collected volume between his narrator's thoughts and feelings during the time of the narrative, and those during the writing of the narrative. See text comparison page.

In three other points the Martian physiology differs from ours.

GANGNES: There are many small changes made to the descriptions of the Martians for the collected volume (see text comparison page). A seemingly nitpicky one is that every instance of a present-tense state of being (e.g., "differs," "do," "have," etc.) is past-tense in the volume. This is perhaps not a material difference, but it does affect the reader's understanding of whether the Martians might still be around at the end of the narrative, and/or if human beings can no longer consider Martians to be a thing of the past even if they defeat them; the Martians still exist on other planets.

the case with the ants

GANGNES: Ants do sleep, though not in the same way humans or many other animals do.

More information:

wonderful

GANGNES: In this case, strange and unbelievable (not inherently a good thing).

budded off just as young lily bulbs

From DANAHAY 145: "the bulbs of a lily that reproduce by budding off from each other through the process of fission, a form of asexual reproduction"

fresh water polyp

From MCCONNELL 246: "a sedentary marine animal with a fixed base like a plant, and sensitive tendrils (palp) around its mouth with which it snares its prey"

From DANAHAY 145: "a sedentary type of animal form characterized by a more or less fixed base, columnar body, and free end with mouth and tentacles"

Tunicates

From MCCONNELL 246: "marine animals with saclike bodies and two protruding openings for the ingestion and expulsion of water (their means of locomotion)"

From STOVER 190: "The Tunicates ... are Sea Squirts, belonging to the Urchordata, a subphylum of chordata or 'vertebrated animals [to which they are] first cousins.'"

From DANAHAY 146: "a subspecies of sea animals that have saclike bodies and minimal digestive systems"

the case.

GANGNES: The 1898 version of the novel adds two paragraphs here about the thoughts of "a certain speculative writer of quasi-scientific repute" on Martian technology and anatomy. This is commonly thought to be a cheeky reference to Wells himself. See text comparison page.

But of that I will write more at length later.

GANGNES: This line is replaced in the 1898 volume with "A hundred diseases, all the fevers and contagions of human life, consumption, cancers, tumours and such morbidities, never enter the scheme of their life." This constitutes a subtle foreshadowing about the ultimate fate of the Martians and is perhaps a bit more elegantly constructed than the serial's sentence.

carmine

From DANAHAY 147: bright red

I found it broadcast

GANGNES: The narrator heard about the Red Weed spreading across England through its waterways.

a stream of water.