The river sweats Oil and tar

Nature defiled by the unreal city

The river sweats Oil and tar

Nature defiled by the unreal city

London Bridge is falling down falling down falling down

I find this reference to the London bridge interesting here. The last time it was mentioned in the poem was the end of the first book. This seems to bring the poem full circle by having the first and last book end with a similar mention while also referencing death

Unreal City

The name of the place he is about to describe being "Unreal City" is fitting because although the setting is a real place and people seem to be acting normal in the beginning, it quickly changes. Suddenly corpses and death are being mentioned as a normal conversation between the people of this city. The poem describes a place in a way that makes it seem almost like an alternate world.

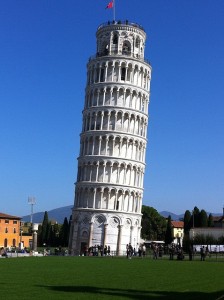

And upside down in air were towers Tolling reminiscent bells, that kept the hours

Throughout the poem Eliot revisits the imagery of towers. Towers are understood as signs of progress, of civic pride, of civic authority. Towers take on this authority.

In these lines, Eliot literally flips the tower function on its head. The tower that is used to establish a sense of time, Eliot uses to dissociate time. At first it seems that time in the present has ceased to function and all that is left is the ghost of that time. However, Eliot seems more interested in the cyclical nature of time given that the poem opens with a discussion of the inevitability of spring. Because of the cyclical nature of time, the tolling bell seems to be both echoes of past chimes and chimes in the present. The present has now lost its significance and each moment has now lost its sense of originality. Eliot has disoriented time and in doing so, he has undermined one of the most important ordering tools in society. The idea of “now” becomes unreal. The significance of time as a tool is echoed in the architecture of the towers. Clocks are positioned on these towers, these pillars of society.

The tower itself is undermined. Earlier, Eliot references falling towers: Jerusalem, Athens, Alexandria, Vienna, and London, which were epic civilizations “in their time.” The reference to falling towers immediately connotes biblical reference to the towers of Babel, which fell when God decided that humans had made too much progress and had become arrogant. All that was left was chaos. Eliot uses towers to undermine the arrogance of the concept of progress and disorients the conception of linear time.

Here is the man with three staves, and here the Wheel, And here is the one-eyed merchant, and this card, Which is blank, is something he carries on his back, Which I am forbidden to see. I do not find The Hanged Man. Fear death by water. 55 I see crowds of people, walking round in a ring.

The ‘Wheel’ represents the circle in which the whole world moves on. The process, how it seems to be presented by unreal cities is nothing but an illusion. Eliot shows that there is no progress, only change that nonetheless does not change anything. A 'wheel' is characterized by having a center around which it is turning all the time. If one relates the poem to Yeat's "The Second Coming" http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/172062 the 'wheel' can be compared to a 'gyre'. The more the gyre is turning, the more it gets away from its center. If the center was nature or a just a specific point in the past, where mankind and nature were more closely connected, it could be interpreted as constantly moving away from 'realness'. In a gyre it is impossible to move to the center; one is constantly pushed towards the outside. The same in a wheel. What is turning on the outside and constantly moving on is disconnected from the center, that stays where it is.

However, the wheel and its center always have to move the same way. Without synchrony the wheel does not work. In a gyre the cycles become bigger and bigger, but still there needs to be synchrony. Modern time in the Waste Land seems to be moving too fast and like a gyre destroying something or approaching 'apocalypse'. The wheel turning faster as its center destroys the synchrony and harmony and hence makes it unreal. So modern time with its unreal cities could be moving on without a center, without a basis or a close connection to something constant. Therefore Eliot mentions the ring, where crowds of people are walking around. Basically like a wheel without a center. Maybe just because they lost the connection to the nature, the center of human nature. In comparison to a ring, a wheel has spokes that lead to the center. Spokes that make a connection and therefore make it real.

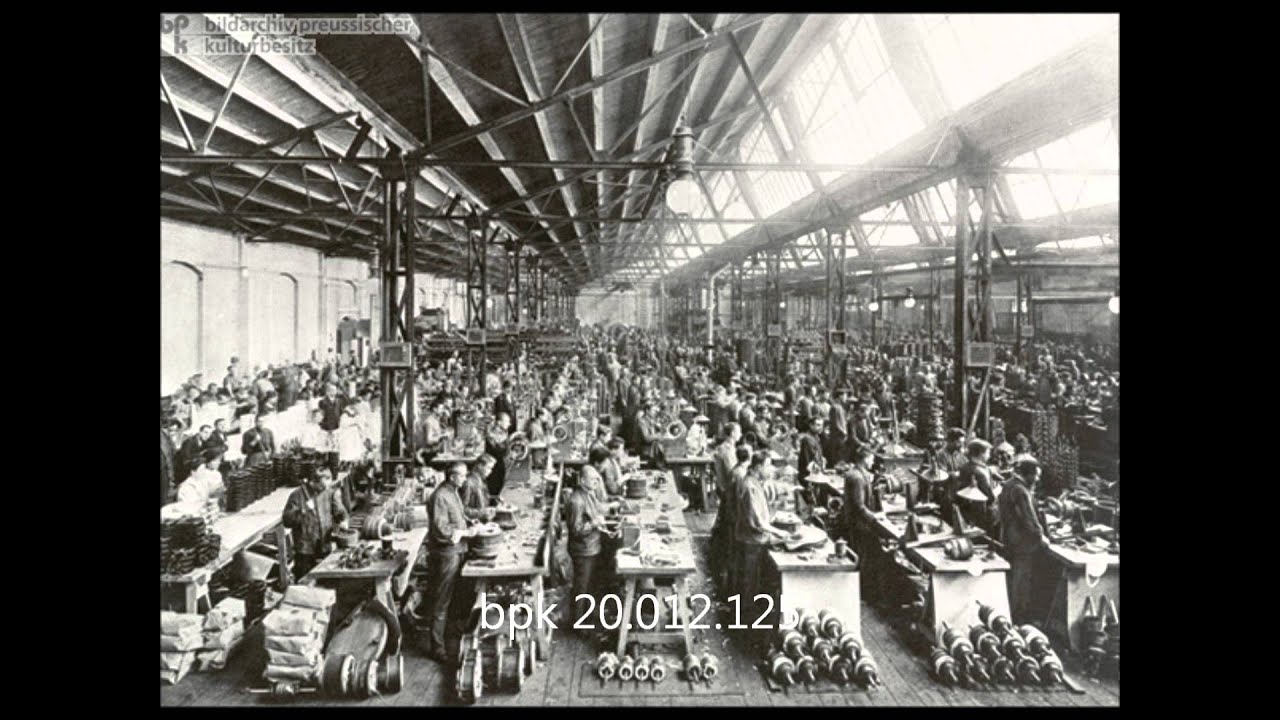

‘Crowds of people, walking round in a ring’ alludes to ghostly figures created by an unreal city. For example in an industrialized world, in big cities, where people go to work every day and just follow the crowd. Cities, civilization and culture pretend to lead people somewhere and to make them move on. They think they have a destination. However, they do not move on, but stay in that circle.

The ‘Wheel’ capitalized stands for a higher power that makes the system move. A wheel literally standing for a new invention and for progress does not apply in this context, it stands for something higher or even godlike.

The clairvoyante could therefore just stand for mankind’s predetermined destiny and the ‘one-eyed merchant’ stands for another aspect of an unreal city. In the modern world, due to the consequences of the industrialization, there is a big difference between rural and urban areas. Cities stand for agglomeration of people, capital and products. The ‘one-eyed merchant’ however, seems not to see the ‘whole thing’. He seems to be blinded by the illusion of the unreal cities and the modern world. This also refers to Eliot’s rejection of a modern world. In a city, people just follow the mainstream and believe in non-existing things, they are not alive and conscious, but just ghostly figures.

Furthermore, the ‘one-eyed merchant’ carries something on his back, which the clairvoyante cannot see. It is a blank card. It seems like a burden for humanity that men must carry, especially the one-eyed merchant, as a representative of a ‘modern urban man’. If the clairvoyante cannot see it, it might contradict the fact that the future is pre-determined and hence the ‘Wheel’ can be interpreted differently. The blank card could mean that there is still a possibility to change the future and that people are able to act. The ‘Wheel’ itself is just turning around its center, but seen as a whole the ‘Wheel’ could be moving on.

The river’s tent is broken: the last fingers of leaf Clutch and sink into the wet bank. The wind Crosses the brown land, unheard. The nymphs are departed.

The river referred to is the Thames River in London. During the Industrial Revolution (1760-1820) when factories and mass production were on the rise in Europe, the urbanization and industrialization of the society caused sewage and waste to spill into the Thames River. Eliot mentions this pollution: “The river sweats / Oil and tar” (266-267). Sea creatures were thriving in the river, but by late 1850s the creatures disappeared. What was once a natural habitat for these animals became a contaminated waste.

The river’s shelter can be interpreted as a tree hovering over the river and protecting it. The shelter is now destroyed and has fallen and collapsed into its inhabitant causing the leaves to fall into the river. The river is displaced. The images of fallen leaves and brown land suggest a dull and ruined civilization. The brown land could be referencing a polluted land. The river bears “empty bottles, sandwich papers, Silk handkerchiefs, cardboard boxes, cigarette ends” (177-178). The material items brought by modern civilization have caused the destruction of the once clean and pure river. The civilization has become a wasteland. This vision of the unreal city is filthy resulting in the deterioration of modern civilization.

Nymphs are spirits of nature. This land that was once was considered a thriving and flourishing civilization filled with nature is diminished, causing the nymphs to leave. This introduces the concept of anti-progress. At a time when industrialization and technology is advancing, society is deteriorating. This land is no longer of nature. The nymphs have left because the land is of un-nature occupied by material waste caused by civilization. The brown land is deserted and deteriorated. This land is now in ruins. The brown land has become a ghost town.

As modern civilization progresses, society continues to shatter, which will eventually lead to the civilization's downfall. Another instance of this occurrence is in the "Falling towers Jerusalem Athens Alexandria / Vienna London / Unreal"(373-376). This represents the destruction of civilization as a consequence of the advancement of modern civilization. The falling towers of the ancient and modern cities is the aftermath of the continuous ruin of civilizations. Anti-progress in modern civilization is so disastrous and devastating that it terminates civilization as a whole.

With a shower of rain; we stopped in the colonnade, And went on in sunlight, into the Hofgarten, 10 And drank coffee, and talked for an hour.

The Hofgarten used to be a residence representing the old Europe, which consisted of empires ruled by monarchs. However, World War I and the Russian Revolution changed the political system in Europe completely. Propaganda led to the alienation of the other countries and to the division of the peoples. Multinational empires were split up in a very short time that had existed for so long.

The Hofgarten in Munich is used by Eliot in order to represent the downfall of this political structure and also represents the motif of the unreal city. Due to its downfall the Hofgarten also stands for the motif of a ghost, which once was alive in the past, but now its existence is present even if it does not really exist anymore. An aerial photo of the Hofgarten shows its baroque architecture, very symmetrical, with a huge man-made garden. It still is an unreal, artificial and man-made place. The complete opposite of a waste land of disorder, industry, pollution and grotesqueness. However, going to the Hofgarten is a travel to the past. Eliot mentioning the sunlight seems to show a longing for the past or just a rejection of the fast changing modern world.

The Hofgarten in Munich is used by Eliot in order to represent the downfall of this political structure and also represents the motif of the unreal city. Due to its downfall the Hofgarten also stands for the motif of a ghost, which once was alive in the past, but now its existence is present even if it does not really exist anymore. An aerial photo of the Hofgarten shows its baroque architecture, very symmetrical, with a huge man-made garden. It still is an unreal, artificial and man-made place. The complete opposite of a waste land of disorder, industry, pollution and grotesqueness. However, going to the Hofgarten is a travel to the past. Eliot mentioning the sunlight seems to show a longing for the past or just a rejection of the fast changing modern world.

Time is not seen linear, but rather like a circle. After rain there will be sunshine and then maybe rain again. The weather can be referred to the changing political systems. Like London, Athens or Alexandria, cities (that also stand for a political system or an empire) are not 'real'. Some fall and others rise. It is just an illusion.

Considering the year when the poem was written, many countries in Europe tried to forget the horrible consequence of WWI in the 1920s, so probably many cities also seemed unreal due to an unauthentic/superficial atmosphere. For example Paris and the "années folles" (engl. "the crazy years"), the center of art and entertainment, where Eliot also spend some time, and the reason for Hemingway describing the "Lost Generation". Basically a generation created by the 'unrealness of the city'.

There I saw one I knew, and stopped him, crying “Stetson! You who were with me in the ships at Mylae!

Here, slipped into an otherwise contemporary depiction of the “unreal city” of London, is a reference to the Battle of Mylae, which was fought between Rome and Carthage and took place in 260 BC. Having this bit of dialogue interspersed with imagery of London in 1922 shatters our linear perception of time and the illusion of “progress” upon which unreal cities like London are built, which is precisely what makes them unreal – they’re built upon an illusion, and it’s the illusion that allows a city to exist in the first place. This bit of dialogue throws us back in time abruptly by two thousand years, and the fact that it’s slipped so covertly into an otherwise contemporary passage recalls the clairvoyant’s vision at the beginning of the poem of “the Wheel” and “people walking in circles” at the start of the poem – although the “crowd flow[ing] over London bridge” in this passage are all staunch believers in the illusion of progress and in the fact that they’re moving forward over the bridge, they are, in fact, walking in circles just as people were in 260 BC.

This passage also calls to attention the futility of war, and the fact that it doesn’t matter which battle the speaker was in the ships with Stetson at – whether it was World War I in the 20th century or Mylae so long ago, the result is the same, even if the goals behind them are purportedly different. War just feeds into this illusion that we’re moving forward , in a line, towards some better future, when really we’re “walking in circles” just like before.

When Eliot reinvokes this image of contemporary London under a “brown fog” later on in the poem, he slips “Mr. Eugenides, the Smyrna merchant” (209) into his depiction of the unreal city. Upon first researching Smyrna, I discovered it was an ancient city located in what is now Turkey – meaning that this ancient merchant would have somehow been thrown forward into the modern-day world. This would present London as being just another version of these past, now-fallen “unreal cities” built atop the ruins of those that came before it, and further the idea of time being presented as a circular, rather than linear, thing.

However, upon further research I discovered that The Great Fire of Smyrna was a catastrophe that occurred in the year 1922 – and it couldn’t possibly be a coincidence that this happened in the same year that “The Wasteland” was written. It occurred shortly after the end of Greek occupation of the port city during World War I. This could be another gesture toward the futility of war and how its furthering “progress” is nothing more than an illusion, and also relates to the motif of exile in the poem.

The boundary between past and present is blurred yet again at the mention of “Elizabeth and Leicester” (278) – referring to Queen Elizabeth and Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester – sailing down the Thames later on in the poem. This passage and the one directly preceding it are nearly identical – except that one is taking place on the contemporary Thames, and one on the 16th century Thames, almost 400 years prior. History, in this section, is repeating itself – or perhaps what we think of as being “present” is simply layered on top of what we think of as being “past,” and the distinction between the two is being blurred until they become one in the same thing. London is not only depicted as being built atop the ruins of prior “unreal cities” that also believed in the illusion of progress (but eventually fell, just as it is predicted that London will in this poem) – contemporary London is also being shown as layered atop all of its past phases in history, and somehow all of these phases of history seem to be bleeding into one in this poem. London is not only filled with crowds of modern-day people flooding over London bridge – it is also filled with ghostly figures of times past, and all of them seem to be existing at the same time, furthering the image of the city as being something “unreal.”

It was during the reign of Queen Elizabeth that England became an as important a player in European exploration and imperialism as continental countries like Spain and Portugal [x], and perhaps this is why the poem flashes back to the Elizabethan period rather than any other one, with an image of Elizabeth and Leicester sailing down the Thames juxtaposed with a bleak and worn-out image of the contemporary Thames "sweating oil and tar." It is an image of the British empire after its run its course (just like any other empire), placed beside a hopeful image of a British empire thats still on the rise, and which believes itself to be immortal just like anybody or anything still in its youthful stages.

During the Victorian era not so long before 1922, it was a popular saying that "the sun never set on the British empire," meaning that British imperialism had expanded so far across the globe that the sun always shone upon it at any given time. However, by 1922, the empire that Britain had become by the late Victorian era was already being gradually disbanded, and when the notion of "progress" that the Victorians believed so firmly in was shattered by this "progress" culminating in nothing constructive after all, but rather the destruction of WWI, the empire began to fall apart. Although Britain believed itself to be moving forward toward some higher, more elevated state as its technology progressed, it was proven during the war that humanity was every bit as capable of destructive acts as ever before, and that technology had, if anything, given humankind the means to be more destructive than they had ever been before contemporary technology existed.

British imperialism depended not only upon the illusion of time progressing us toward some higher, more evolved state but also upon the idea that the British had somehow reached this higher state more quickly than the other civilizations they colonized. Britain justified its colonization of other cultures by claiming that they were more enlightened than these other people, and that by colonizing them they were "helping" them reach the same heights of enlightenment as the British. However, when all of Europe's notion of progress was shattered, imperialism could no longer be justified, and the British empire as it existed during the reign of Queen Victoria could no longer hold itself together. The illusory glue that held it together had dissolved, and so it eventually fell apart.

The British empire, in this way, is being depicted by Eliot as the ultimate "unreal city" – a culture that believed so strongly in the illusions upon which it was founded that it has managed to exist for centuries and branched out to span the entire globe – based upon nothing more than a firm belief in the ideology of progress. In 1922, enough people still believed in this notion that the empire hadn't quite shattered to pieces as Eliot predicts that it will by flashing forward at the end of the poem to its ruins. However, the ideological glue holding the empire together was wearing thin as the aftermath of the war prompted people to question the entire notion of progress which was its foundation, and Eliot, who could see the foundation weakening, realized that the center of the empire could not hold, and that Great Britain – which had been unreal from its beginning – was on the verge of falling apart.

A heap of broken images

“A heap of broken images” here is reminiscent of the “falling towers” (373) and the “decayed hole among the mountains” (385) that the ruins at the end of the poem are described as – ruins that could very well have once been London. The fact that the poem begins with this image of ruins and ends with them gestures again toward the circular nature of time pointed out by the clairvoyant at the start of the poem – London was raised out of the ruins of unreal cities and has fallen back into them yet again in this post-apocalyptic depiction of the future, but the ending seems hopeful in that yet another “unreal city” may rise again from the ruins of London later on.

The “heap of broken images” could refer to the heap of ruins of past unreal cities – “images” referring to the fact that these cities/civilizations are nothing more than mirages based upon an illusion of progress, and that this unreal city is the one that will somehow last forever (despite the fact that all of its predecessors whose ruins it was built atop have fallen), and “heap” referring to the fact that they’re all stacked atop one another, and in a way existing at the same time. “Heap” and “broken” also sounds messy – one city doesn’t just fall for another one to cleanly rise from the ruins. New cities always contain remnants or fragments inherited from its predecessors, and contemporary London has many predecessors.

In this way London’s predecessors are a palimpsest upon which London has been written. The old ones have been erased but still exist beneath the fresher writing of London - and someday London, too, will be scratched out for a new unreal city to be written in its place. This shows us that London is in no way exempt from the fate of the “unreal cities” that came before it, despite all of its grand illusions of progress.

This relates to the mention of the Battle of Mylae, The Smyrna Merchant, and Elizabeth and Leicester in that these are all ghostly figures from past unreal cities/past phases in London’s history that are somehow still visible in London in 1922. These figures are like the writing on the palimpsest that have been scratched out to write contemporary London in their place – but despite having been partially erased, they’re still showing through, and their influences are still present in London in the 1920s.

This idea of “broken images” also relates to the concepts of modernism in general and of fragments/“isolate flecks” that we’ve discussed in class with regard to other poetry that was written in the same era as “The Wasteland.” It particularly calls to mind Ezra Pound’s “In a Station of the Metro,” since that poem is a potent depiction of the motif of the “unreal city” contained in just one, concise image.

The fact that the faces described by the speaker in this poem are an “apparition” calls to mind the “apparition” of ghostly figures like Elizabeth and Leicester appearing in contemporary London, and of all ghostly figures from London’s predecessors still existing beneath the unreal city of London. The “heap of broken images” could be referring to a whole pile of images resembling the one contained within “In a Station of the Metro” that makes up the image of the unreal city, which is not just one coherent picture but rather a whole heap of fragmented glimpses. Perhaps this is because in the modern world, everything must be seen in fragments, or glimpses, due to the speed at which things move. Or maybe it’s because London is built atop so many unreal cities that the old ones are peeking through, which may be a sign that the “unreal city” of London has had its time and is coming to an end like all of its predecessors. London is coming apart at the seams and breaking into a “heap of broken images” before it falls entirely, and can no longer exist as one coherent image now that World War I has shattered the illusion of “progress” upon which it depended to stay standing.

“My feet are at Moorgate, and my heart Under my feet. After the event He wept. He promised ‘a new start.’ I made no comment. What should I resent?”

Moorgate was a postern in the London Wall that was initially built by the Romans and was turned into a gate in the 15th century. Moorgate was torn down in 1762, but the name remains as a major street in London today. The name Moorgate is taken from Moorsfield, which was the last open field of the city. The district of Moorgate is presently a financial sector that contains an underground train station.

The speaker may be Queen Elizabeth I accompanied by Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester. Queen Elizabeth I and Robert Dudley, a married man, were rumored to have been in an intimate romantic relationship with one another. They are standing at what may be the ruins of Moorgate after its demolition. Dudley promises a “new start”. She makes no comment and asks herself, “What should I resent?” The queen cannot be bitter towards him or their situation because she understands that there are no such things as new starts in this civilization.

Although Moorgate was once a postern that became an urban metropolitan consisting of an underground train station, there is no such thing as progress and a new start. Modern civilization is degenerating. Madame Sosostris’s card “the Wheel” (51) is a figure of this unachievable new start and progress. This wheel is civilization repeatedly coming full circle and never being able to change or progress. Eliot suggests that whether it's a new start in Queen Elizabeth’s relationship with Dudley or civilization as a whole, there is no such thing as a new start in this modern world.

A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many, I had not thought death had undone so many.

Links with zombies - Cities are actually not progressive, just make us become part of a machine - no individualism

The river’s tent is broken: the last fingers of leaf Clutch and sink into the wet bank. The wind Crosses the brown land, unheard. The nymphs are departed.

The images of fallen leaves and brown land suggest a dull and miserable civilization. The brown land could possibly be referencing a dry and possibly polluted land. Nymphs are spirits of nature. The nymphs are absent from this land, which may be because the land is no longer a flourishing and thriving civilization. This land is no longer of nature. The nymphs have left because the land is of un-nature. The brown land has become a ghost town.

brown fog

this image reminds me of the smog that covers some big cities. Emissions pollute the air and accumulate in a cloud of brown fog above the roofs of the city. The Unreal city is causing pollution and destroying nature.

Falling towers Jerusalem Athens Alexandria Vienna London Unreal

Here, a list of cities that have once been at the center of something/some empire, and are definitely no longer at the center of things anymore (as London is). It's interesting that none of these cities are actually in ruins though, and are still in existence as functioning cities - just not as important as they once were. By listing them all (in Historical order, I think?) and ending in London, Eliot seems to be saying that London will fade just as all of its predecessors - who also believed in the idea of "progress" – did before it.

The cities are "unreal" because they are built upon this idea of progress, which is really just the illusion that time is taking us somewhere different/better than where we are today.

Elizabeth and Leicester

Referring to Queen Elizabeth and Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester.

Another example of unreal cities/past and present civilizations being layered on top on each other. This passage and the one preceding it are almost identical - except that one is taking place on the contemporary Thames, and one on the 16th century Thames, almost 400 years prior. History, in this section, is repeating itself, and time is moving in a circular motion (like the Wheel/people walking in circles seen by the clairvoyant).

This also speaks to the idea of the "ghost city" that we discussed in class - Elizabeth and Leicester, the Smyrna merchant, and the person who fought at Mylae are all ghosts from past unreal cities haunting the present one. Or you could eliminate the idea of "past" and "present" completely, and say that all of these cities are existing at the same time/occupying the same space, and that none of the past unreal cities are as "past" as we think of them as being.

Ringed by the flat horizon only What is the city over the mountains

Here the "unreal city" is presented as a mirage seen over the horizon - something that will fade once you get too near to it. The wet/dry motif also seems to be connected with the unreal city motif in that wetness is related to civilization and dryness is related to the fall of civilizations. But wetness is also connected with being wrapped up in this mirage of the unreal city/illusion of progress, and results in "drowning the senses" and an inability to think clearly. Dryness seems to be associated with moments of clarity and seeing the bigger picture of things, the circular nature of time, and the fact that our linear idea of time and progress is just a mirage.

Unreal City Under the brown fog of a winter noon Mr. Eugenides, the Smyrna merchant

Like in the preceding "Unreal City" passage, in which London is also being depicted under a "brown fog," our linear perception of time/progress is being undermined here. In the last passage, the speaker mentions having fought in the battle of Mylae with somebody - a battle that took place in 260 BC - despite the fact that the passage, other than that, takes place in contemporary London.

Now, in another otherwise contemporary London passage, a "Smyrna merchant" is slipped in. Smyrna was an ancient city located in what is now modern-day Turkey, but this ancient merchant is existing in a modern-day world. This (and the Mylae passage) present London as being just another version of these past, now-fallen "unreal cities," built atop the ruins of what came before it.

I really liked Prof. Hanley's image of these past cities being a palimpsest (a word I didn't know!) and London being yet another unreal city written atop the old ones which have been erased but which still exist beneath it - someday London, too, will be scratched out for a new unreal city to be written in its place. The mention of Mylae and the Smyrna merchant give us glimpses of the scratched-out words of past civilizations, and show us that today's unreal city is in no way special/exempt from eventual destruction like those that came before it.

There I saw one I knew, and stopped him, crying: “Stetson! “You who were with me in the ships at Mylae!

Although this scene clearly takes place in contemporary London (at least up until this line), Mylae was a battle between Rome and Carthage that took place in 260 BC. This is another point in the poem where our linear perception of time is shattered. Either we've been thrown back, suddenly, from 1922 to 260 BC at this point in the poem, showing that people have been walking in circles in the same way since then, or this line is making the point that it doesn't matter what battle they were in the ships together at - whether it's World War I in the 20th century or Mylae so long ago. All of the battles that are fought, even if they give the illusion of progress toward something/furthering some cause or goal, are the same. We're moving in circles no matter how many battles are fought for however many reasons – and the result of battles is always the same, even if the goals behind them are purportedly different.

I see crowds of people, walking round in a ring.

Possibly relating to "the Wheel" mentioned a few lines prior and "the crowd flowing over London bridge" mentioned in the next stanza - these people, inhabiting the "unreal city" of London, believe that they're going somewhere by walking over London bridge with all of the others in the crowd - going somewhere, doing something with their lives, making progress toward something bigger. The clairvoyant, however, is able to see the bigger picture in a way that these people aren't - she sees that these people walking forward is only an illusion, and that they're really walking in circles, just as people have always done and will do again. She is shattering their illusion of progress, the illusion upon which the building of "unreal cities" depends.

What are the roots that clutch, what branches grow Out of this stony rubbish? Son of man, You cannot say, or guess, for you know only A heap of broken images,

The "stony rubbish" and "heap of broken images" could be previews of the post-apocalyptic world of ruined cities depicted in the last section of the poem. Also, the fact that the poem begins with these ruins and ends with them as well shatters our linear notion of time moving us toward something, and shows it to be something circular. We begin with an unreal city growing from the "stony rubbish" (of a past city) and end with it falling back into the stony rubbish yet again.

"Son of man," however, doesn't have the power to perceive this circular repetition of things - he, and all humans, know only "a heap of broken images," which could really describe the entire poem – a heap of broken images of Europe in the 1920s, yet another "unreal city" that is in the process of falling down like all the ones that preceded it. However, this "Son of man" and all people who are a part of this world are too immersed in these broken images to perceive the circular nature of time - they are too caught up in their own time to see the bigger picture.

Unreal

the sandy road

Unreal City

Departed, have left no addresses

river’s tent

rats’ alley

throne

In this decayed hole among the mountains

Referring to the now ruined "unreal cities" mentioned previously in the poem, and people are living in them - maybe a prediction of the future, that all of the "towers" of these great cities will eventually fall and become ruins - or that they're already falling?

Above the antique mantel was displayed As though a window gave upon the sylvan scene

Rather than a real, natural sylvan scene seen through a window, an image of a natural scene unnaturally depicted in a painting hanging in a wholly unnatural, sumptuously decorated room - material objects/displays of wealth used as a substitute for nature here.

London Bridge is falling down falling down falling down

stumbling in cracked earth

What is the city over the mountains Cracks and reforms and bursts in the violet air Falling towers

Trams and dusty trees.

Falling towers Jerusalem Athens Alexandria Vienna London Unreal