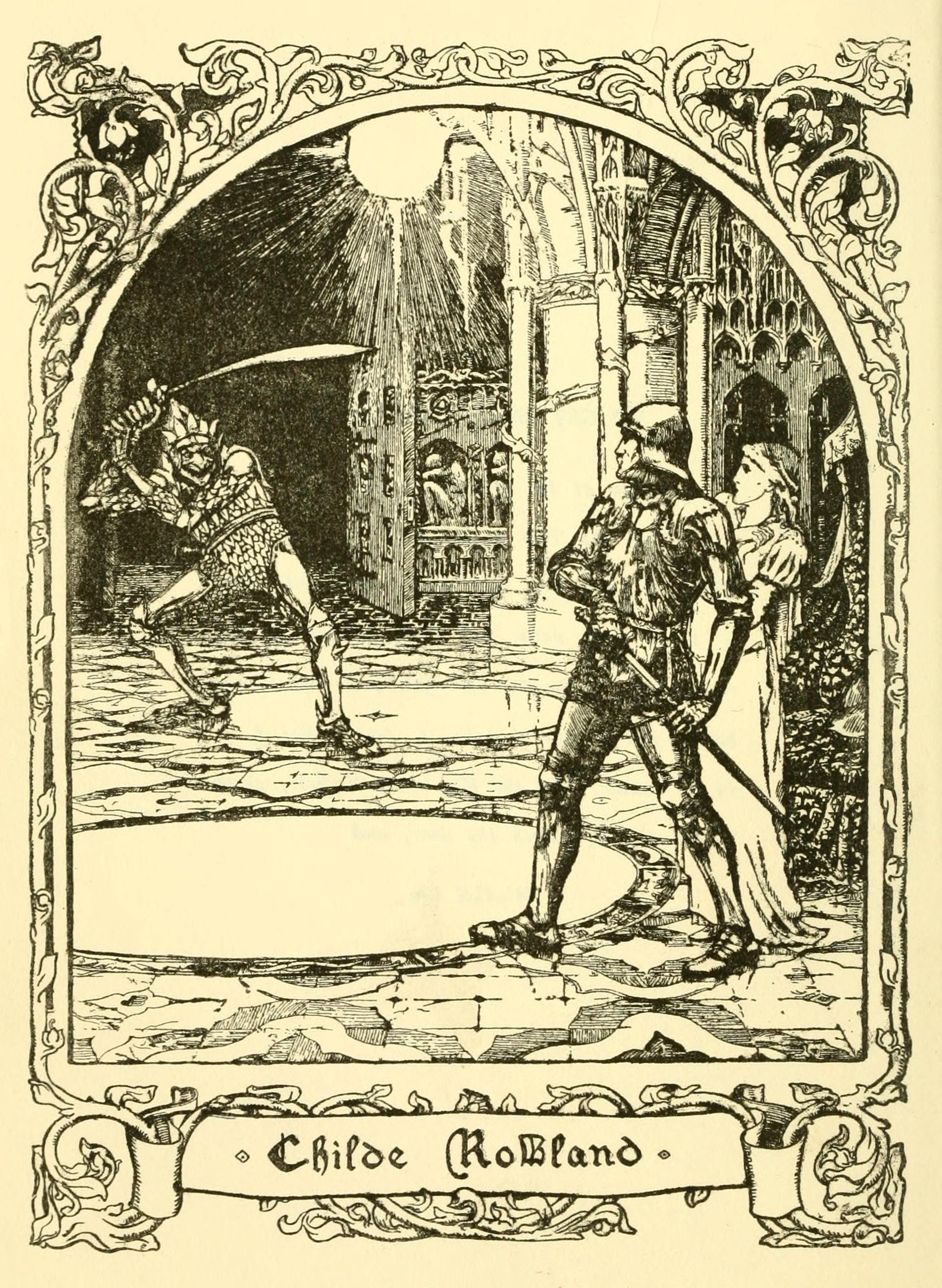

“Childe Roland to the Dark Tower came.”

Clearly, the poem’s closing declaration has reverberated far beyond Victorian poetry. T. S. Eliot draws on its ruinous landscape in "The Waste Land", while Stephen King’s Dark Tower series recasts Roland’s quest as the foundation of his expansive fantasy epic. Its influence continues across speculative fiction: Alan Garner’s Elidor reimagines Roland as a modern quester, Roger Zelazny alludes to Browning in Sign of the Unicorn, Philip José Farmer quotes the poem in The Dark Design, John Connolly features it in The Book of Lost Things, and Alastair Reynolds names a doomed explorer Roland Childe in Diamond Dogs. These afterlives reveal the poem’s flexibility, as each era reshapes the Tower according to its own anxieties. Readers encountering the Tower today therein participate in a long tradition of reinterpretation, proving that Browning’s ambiguous ending is part of what gives the poem lasting cultural life.

This

This