Note: This response was posted by the corresponding author to Review Commons. The content has not been altered except for formatting.

Learn more at Review Commons

Reply to the reviewers

Reviewer #1 (Evidence, reproducibility and clarity (Required)):

Summary

The manuscript by Aarts et al. explores the role of GRHL2 as a regulator of the progesterone receptor (PR) in breast cancer cells. The authors show that GRHL2 and PR interact in a hormone-independent manner and based on genomic analyses, propose that they co-regulate target genes via chromatin looping. To support this model, the study integrates both newly generated and previously published datasets, including ChIP-seq, CUT&RUN, RNA-seq, and chromatin interaction assays, in breast cancer cell models (T47DS and T47D).

Major comments:

R1.1 Novelty of GRHL2 in steroid receptor biology

The role of GRHL2 as a co-regulator of steroid hormone receptors has previously been described for ER (J Endocr Soc. 2021;5(Suppl 1):A819) and AR (Cancer Res. 2017;77:3417-3430). In the ER study, the authors also employed a GRHL2 ΔTAD T47D cell model. Therefore, while this manuscript extends GRHL2 involvement to PR, the contribution appears incremental rather than conceptual.

We are fully aware of the previously described role of GRHL2 as a co-regulator of steroid hormone receptors, particularly ER and AR. As acknowledged in our introduction (lines 104-108), we explicitly state: "Grainyhead-like 2 (GRHL2) has recently emerged as a potential pioneer factor in hormone receptor-positive cancers, including breast cancer21. However, nearly all studies to date have focused on GRHL2 in the context of ER and estrogen signaling, leaving its role in PR- and progesterone-mediated regulation unexplored22-26".

As for the specific publications that the reviewer refers to: The first refers to an abstract from an annual meeting of the Endocrine Society. As we have been unable to assess the original data underpinning the abstract - including the mentioned GRHL2 DTAD model - we prefer not to cite this particular reference. We do cite other work by the same authors (Reese et al. 2022, our ref. 25). We also cite the AR study mentioned by the reviewer (our ref. 55) in our discussion. As such, we think we do give credit to prior work done in this area.

By characterizing GRHL2 as a co-regulator of the progesterone receptor (PR), we expand on the current understanding of GRHL2 as a common transcriptional regulator within the broader context of steroid hormone receptor biology. Given that ER and PR are frequently co-expressed and active within the same breast cancer cells, our findings raise the important possibility that GRHL2 may actively coordinate or modulate the balance between ER- and PR-driven transcriptional programs, as postulated in the discussion paragraph.

Importantly, we also functionally link PR/GRHL2-bound enhancers to their target genes (Fig5), providing novel insights into the downstream regulatory networks influenced by this interaction. These results not only offer a deeper mechanistic understanding of PR signaling in breast cancer but also lay the groundwork for future comparative analyses between GRHL2's role in ER-, AR-, and PR-mediated gene regulation.

As such, we respectfully suggest that our work offers more than an incremental advance in our knowledge and understanding of GRHL2 and steroid hormone receptor biology.

R1.2 Mechanistic depth

The study provides limited mechanistic insight into how GRHL2 functions as a PR co-regulator. Key mechanistic questions remain unaddressed, such as whether GRHL2 modulates PR activation, the sequential recruitment of co-activators/co-repressors, engages chromatin remodelers, or alters PR DNA-binding dynamics. Incorporating these analyses would considerably strengthen the mechanistic conclusions.

Although our RNA-seq data demonstrate that GRHL2 modulates the expression of PR target genes, and our CUT&RUN experiments show that GRHL2 chromatin binding is reshaped upon R5020 exposure, we acknowledge that we have not further dissected the molecular mechanisms by which GRHL2 functions as a PR co-regulator.

We did consider several follow-up experiments to address this, including PR CUT&RUN in GRHL2 knockdown cells, CUT&RUN for known co-activators such as KMT2C/D and P300, as well as functional studies involving GRHL2 TAD and DBD mutants. However, due to technical and logistical challenges, we were unable to carry out these experiments within the timeframe of this study.

That said, we fully recognize that such approaches would provide deeper mechanistic insight into the interplay between PR and GRHL2. We have therefore explicitly acknowledged this limitation in our limitations of the study section (line 502-507) and mention this as an important avenue for future investigation.

R1.3 Definition of GRHL2-PR regulatory regions (Figure 2)

The 6,335 loci defined as GRHL2-PR co-regulatory regions are derived from a PR ChIP-seq performed in the presence of hormone and a GRHL2 ChIP-seq performed in its absence. This approach raises doubts about whether GRHL2 and PR actually co-occupy these regions under ligand stimulation. GRHL2 ChIP-seq experiments in both hormone-treated and untreated conditions are necessary to provide stronger support for this conclusion.

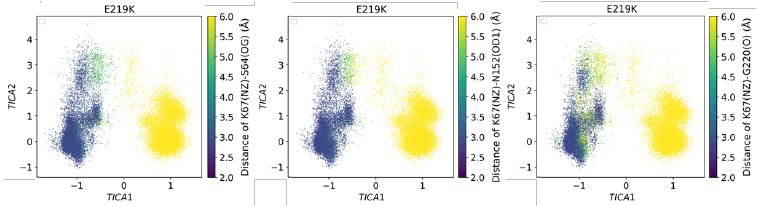

Although bulk ChIP-seq cannot definitively demonstrate simultaneous binding of PR and GRHL2 at the same genomic regions, we agree that the ChIP-seq experiments we present do not provide a definitive answer on if GRHL2 and PR co-occupy these regions under ligand stimulation. As a first step to address this, we performed CUT&RUN experiments for both GRHL2 and PR under untreated and R5020-treated conditions. These experiments revealed a subset of overlapping PR and GRHL2 binding sites (approximately {plus minus}5% of the identified PR peaks under ligand stimulation).

We specifically chose CUT&RUN to minimize artifacts from crosslinking and sonication, thereby reducing background and enabling the mapping of high-confidence direct DNA-binding events: Given that a fraction of GRHL2 physically interacts with PR (Fig1D), it is possible that ChIP-seq detects indirect binding of GRHL2 at PR-bound sites and vice versa. CUT&RUN, by contrast, allows us to identify direct binding sites with higher confidence.

Nonetheless, although outside the scope of the current manuscript, we agree that a dedicated GRHL2 ChIP with and without ligand stimulation would provide additional insight, and we have accordingly added this suggestion to the discussion (line 502-507).

R1.4 Cell model considerations

The manuscript relies heavily on the T47DS subclone, which expresses markedly higher PR levels than parental T47D cells (Aarts et al., J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 2023; Kalkhoven et al., Int J Cancer 1995). This raises concerns about physiological relevance. Key findings, including co-IP and qPCR-ChIP experiments, should be validated in additional breast cancer models such as parental T47D, BT474, and MCF-7 cells to generalize the conclusions. Furthermore, data obtained from T47D (PR ChIP-seq, HiChIP, CTCF and Rad21 ChIP-seq) and T47DS (RNA-seq, CUT&RUN) are combined along the manuscript. Given the substantial differences in PR expression between these cell lines, this approach is problematic and should be reconsidered.

We agree that physiological relevance is important to consider. Here, all existing model systems have some limitations. In our experience, it is technically challenging to robustly measure gene expression changes in parental T47D cells (or MCF7 cells, for that matter) in response to progesterone stimulation (Aarts et al., J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 2023). As we set out to integrate PR and GRHL2 binding to downstream target gene induction, we therefore opted for the most progesterone responsive model system (T47DS cells). We agree that observations made in T47D and T47DS cells should not be overinterpreted and require further validation. We have now explicitly acknowledged this and added it to the discussion (line 507-509).

As for the reviewer's suggestion to use MCF7 cells: apart from its suboptimal PR-responsiveness, this cell line is also known to harbor GRHL2 amplification, resulting in elevated GRHL2 levels (Reese et al., Endocrinology2019). By that line of reasoning, the use of MCF7 cells would also introduce concerns about physiological relevance. That being said, and as noted in the discussion (line 390-391), the study by Mohammed et al. which identified GRHL2 as a PR interactor using RIME, was performed in both MCF7 and T47D cells. This further supports the notion that the PR-GRHL2 interaction is not limited to a single cell line.

R1.5 CUT&RUN vs ChIP-seq data

The CUT&RUN experiments identify fewer than 10% of the PR binding sites reported in the ChIP-seq datasets. This discrepancy likely results from methodological differences (e.g., absence of crosslinking, potential loss of weaker binding events). The overlap of only 158 sites between PR and GRHL2 under hormone treatment (Figure 3B) provides limited support for the proposed model and should be interpreted with greater caution.

We acknowledge the discrepancy between the number of binding sites between ChIP-seq and CUT&RUN. Indeed, methodological differences likely contribute to the differences in PR binding sites reported between the ChIP-seq and CUT&RUN datasets. As the reviewer correctly notes, the absence of crosslinking and sonication in CUT&RUN reduces detection of weaker binding events. However, it also reduces the detection of indirect binding events which could increase the reported number of peaks in ChIPseq data (e.g. the common presence of "shadow peaks").

As also discussed in our response to R1.3, we deliberately chose the CUT&RUN approach to enable the identification of high-confidence direct DNA-binding events. Since GRHL2 physically interacts with PR, ChIP-seq could potentially capture indirect binding of GRHL2 at PR-bound sites, and vice versa. By contrast, CUT&RUN primarily captures direct DNA-protein interactions, offering a more specific binding profile. Thus, while the number of CUT&RUN binding sites is much smaller than previously reported by ChIP-seq, we are confident that they represent true, direct binding events.

We would also like to emphasize that the model presented in figure 6 does not represent a generic or random gene, but rather a specific gene that is co-regulated by both GRHL2 and PR. In this specific case, regulation is proposed to occur via looping interactions from either individual TF-bound sites (e.g., PR-only or GRHL2-only) or shared GRHL2/PR sites. We do not propose that only shared sites are functionally relevant, nor do we assume that GRHL2 and PR must both be directly bound to DNA at these shared sites. Therefore, overlapping sites identified by ChIP-seq-potentially reflecting indirect binding events-could indeed be missed by CUT&RUN, yet still contribute to gene regulation. To clarify this, we have revised the main text (line 331-334) and the legend of Figure 6 to explicitly state that the model refers to a gene with established co-regulation by both GRHL2 and PR.

R1.6 Gene expression analyses (Figure 4)

The RNA-seq analysis after 24 hours of hormone treatment likely captures indirect or secondary effects rather than the direct PR-GRHL2 regulatory program. Including earlier time points (e.g., 4-hour induction) in the analysis would better capture primary transcriptional responses. The criteria used to define PR-GRHL2 co-regulated genes are not convincing and may not reflect the regulatory interactions proposed in the model. Strong basal expression changes in GRHL2-depleted cells suggest that much of the transcriptional response is PR-independent, conflicting with the model (Figure 6). A more straightforward approach would be to define hormone-regulated genes in shControl cells and then examine their response in GRHL2-depleted cells. Finally, integrating chromatin accessibility and histone modification datasets (e.g., ATAC-seq, H3K27ac ChIP-seq) would help establish whether PR-GRHL2-bound regions correspond to active enhancers, providing stronger functional support for the proposed regulatory model.

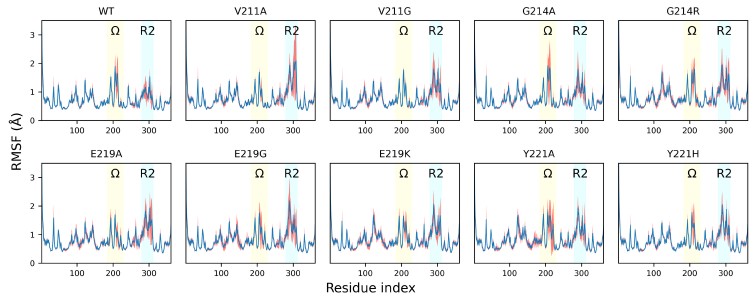

We thank the reviewer for pointing this out. We now recognize that our criteria for selecting PR/GRHL2 co-regulated genes were not clearly described. To address this, we have revised our approach as per the reviewer's suggestion: we first identified early and sustained PR target genes based on their response at 4 and 24 hours of induction and subsequently overlaid this list with the gene expression changes observed in GRHL2-depleted cells. This revised approach reduced the amount of PR-responsive, GRHL2 regulated target genes from 549 to 298 (46% reduction). We consequently updated all following analyses, resulting in revised figures 4 and 5 and supplementary figures 2,3 and 4. As a result of this revised approach, the number of genes that are transcriptionally regulated by GRHL2 and PR (RNAseq data) that also harbor a PR loop anchor at or near their TSS after 30 minutes of progesterone stimulation (PR HiChIP data) dropped from 114 to 79 (30% reduction). We thank the reviewer for suggesting this more straightforward approach and want to emphasize that our overall conclusions remain unaltered.

As above in our response to R1.3, we want to emphasize that the model presented in figure 6 does not depict a generic or randomly chosen gene, but a gene that is specifically co-regulated by both GRHL2 and PR. We also want to emphasize that the majority of GRHL2's transcriptional activity is PR-independent. This is consistent with the limited fraction of GRHL2 that co-immunoprecipitated with PR (Figure 1D), and with the well-established roles of GRHL2 beyond steroid receptor signaling. In fact, the overall importance of GRHL2 for cell viability in T47D(S) cells is underscored by our inability to generate a full knockout (multiple failed attempts of CRISPR/Cas mediated GRHL2 deletion in T47D(S) and MCF7 cells), and by the strong selection we observed against high-level GRHL2 knockdown using shRNA.

As for the reviewer's suggestion to assess whether GRHL2/PR co-bound regions correspond to active enhancers by integrating H3K27ac and ATAC-seq data: We have re-analyzed publicly available H3K27ac and ATAC-seq datasets from T47D cells (references 42 and 43). These analyses are now added to figure 2 (F and G). The H3K27Ac profile suggests that GRHL2-PR overlapping sites indeed correspond to more active enhancers (Figure 2F), with a proposed role for GRHL2 since siGRHL2 affects the accessibility of these sites (Figure 2G).

Minor comments

Page 19: The statement that "PR and GRHL2 trigger extensive chromatin reorganization" is not experimentally supported. ATAC-seq would be an appropriate method to test this directly.

We agree with the reviewer and have removed this sentence, as it does not contribute meaningfully to the flow of the manuscript.

Prior literature on GRHL2 as a steroid receptor co-regulator should be discussed more thoroughly.

We now added additional literature on GRHL2 as a steroid hormone receptor co-regulator in the discussion (line 397-401) and we cite the papers suggested by R1 in R1.1 (references 25 and 54).

Reviewer #1 (Significance (Required)):

The identification of novel PR co-regulators is an important objective, as the mechanistic basis of PR signaling in breast cancer remains incompletely understood. The main strength of this study lies in highlighting GRHL2 as a factor influencing PR genomic binding and transcriptional regulation, thereby expanding the repertoire of regulators implicated in PR biology.

That said, the novelty is limited, given the established roles of GRHL2 in ER and AR regulation. Mechanistic insight is underdeveloped, and the reliance on an engineered T47DS model with supra-physiological PR levels reduces the general impact. Without validation in physiologically relevant breast cancer models and clearer separation of direct versus indirect effects, the overall advance remains modest.

The manuscript will be of interest to a specialized audience in the fields of nuclear receptor signaling, breast cancer genomics, and transcriptional regulation. Broader appeal, including translational or clinical relevance, is limited in its current form.

We have addressed all of these points in our response above and agree that with our implemented changes, this study should reach (and appeal to) an audience interested in transcriptional regulation, chromatin biology, hormone receptor signaling and breast cancer.

Reviewer #2 (Evidence, reproducibility and clarity (Required)):

The authors present a study investigating the role of GRHL2 in hormone receptor signaling. Previous research has primarily focused on GRHL2 interaction with estrogen receptor (ER) and androgen receptor (AR). In breast cancer, GRHL2 has been extensively studied in relation to ER, while its potential involvement with the progesterone receptor (PR) remains largely unexplored. This is the rationale of this study to investigate the relation between PR and GRHL2. The authors demonstrate an interaction between GRHL2 and PR and further explore this relationship at the level of genomic binding sites. They also perform GRHL2 knockdown experiments to identify target genes and link these transcriptional changes back to GRHL2-PR chromatin occupancy. However, several conceptual and technical aspects of the study require clarification to fully support the authors' conclusions.

R2.1 Given the high sequence similarity among GRHL family members, this raises questions about the specificity of the antibody used for GRHL2 RIME. The authors should address whether the antibody cross-reacts with GRHL1 or GRHL3. For example, GRHL1 shows a higher log fold change than GRHL2 in the RIME data.

Indeed, GRHL1, GRHL2, and GRHL3 are structurally related. They share a similar domain organization and are all {plus minus}70kDa in size. Sequence similarity is primarily confined to the DNA-binding domain, with GRHL2 and GRHL3 showing 81% similarity in this region, and GRHL1 showing 63% similarity to GRHL2/3 (Ming, Nucleic Acids Res 2018).

The antibody used, sourced from the Human Protein Atlas, is widely used in the field. It targets an epitope within the transactivation domain (TAD) of GRHL2-a region with relatively low sequence similarity to the corresponding domains in GRHL1 and GRHL3.

We assessed the specificity of the antibody using western blotting (Supplementary Figure 2A) in T47DS wild-type and GRHL2 knockdown cells. As expected, GRHL2 protein levels were reduced in the knockdown cells providing convincing evidence that the antibody recognizes GRHL2. The remaining signal in shGRHL2 knockdown cells could either be due to remaining GRHL2 protein or due to the antibody detecting GRHL1/3. Furthermore, the observed high log-fold enrichment of GRHL1 in our RIME may reflect known heterodimer formation between GRHL1 and GRHL2, rather dan antibody cross-reactivity. As such, we cannot formally rule out cross-reactivity and have mentioned this in the limitations section (line 497-501).

R2.2 In addition, in RIME experiments, one would typically expect the bait protein to be among the most highly enriched proteins compared to control samples. If this is not the case, it raises questions about the efficiency of the pulldown, antibody specificity, or potential technical issues. The authors should comment on the enrichment level of the bait protein in their data to reassure readers about the quality of the experiment.

We agree with the reviewer that this information is crucial for assessing the quality of the experiment. We have therefore added the enrichment levels (log₂ fold change of IgG control over pulldown) to the methods section (line 592).

As the reviewer notes, GRHL2 was not among the top enriched proteins in our dataset. This is due to unexpectedly high background binding of GRHL2 to the IgG control antibody/beads, for which we currently have no explanation. As a result, although we detected many unique GRHL2 peptides, observed high sequence coverage (>70%), and GRHL2 ranked among the highest in both iBAQ and LFQ values, its relative enrichment was reduced due to the elevated background. During our RIME optimization, Coomassie blue staining of input and IP samples revealed a band at the expected molecular weight of GRHL2 in the pull down samples that was absent in the IgG control (see figure 1 for the reviewer below, 4 right lanes), supporting the conclusion that GRHL2 is specifically enriched in our GRHL2 RIME samples. Combined with enrichment of some of the expected interacting proteins (e.g. KMT2C and KMT2D), we are convinced that the experiment of sufficient quality to support our conclusions.

Figure 1 for reviewer: Coomassie blue staining of input and IP GRHL2 and IgG RIME samples. NT = non-treated, T = treated.

R2.3 The authors report log2 fold changes calculated using iBAQ values for the bait versus IgG control pulldown. While iBAQ provides an estimate of protein abundance within samples, it is not specifically designed for quantitative comparison between samples without appropriate normalization. It would be helpful to clarify the normalization strategy applied and consider using LFQ intensities.

We understand the reviewer's concern. Due to the high background observed in the IgG control sample (see R2.2), the LFQ-based normalization did not accurately reflect the enrichment of GRHL2, which was clearly supported by other parameters such as the number of unique peptides (see rebuttal Table 1). After discussions with our Mass Spectrometry facility, we decided to consider the iBAQ values-which reflect the absolute protein abundance within each sample-as a valid and informative measure of enrichment. In the context of elevated background levels, iBAQ provides an alternative and reliable metric for assessing protein enrichment and was therefore used for our interactor analysis.

Unique peptides

IBAQ GRHL2

IBAQ IgG

LFQ GRHL2

LFQ IgG

GRHL2

52

1753400.00

155355.67

5948666.67

3085700.00

GRHL1

23

56988.33

199.03

334373.33

847.23

*Table 1. Unique peptide, IBAQ and LFQ values of the GRHL2 and IgG pulldowns for GRHL2 and GRHL1 *

R2.4 Other studies have reported PR RIME, which could be a valuable source to investigate whether GRHL proteins were detected.

We thank the reviewer for pointing this out. We are aware of the PR RIME, generated by Mohammed et al., which we refer to in the discussion (lines 390-391). This study indeed identified GRHL2 as a PR-interacting protein in MCF7 and T47D cells. Although they do not mention this interaction in the text, the interaction is clearly indicated in one of the figures from their paper, which supports our findings. To our knowledge, no other PR RIME datasets in MCF7 or T47D cells have been published to date.

R2.5 In line 137, the term "protein score" is mentioned. Could the authors please clarify what this means and how it was calculated.

We agree that this point was not clearly explained in the original text. The scores presented reflect the MaxQuant protein identification confidence, specifically the sum of peptide-level scores (from Andromeda), which indicates the relative confidence in protein detection. We have now added this clarification to line 137 and to the legend of Figure 1.

R2.6 In line 140-141. The fact that GRHL2 interacts with chromatin remodelers does not by itself prove that GRHL2 acts as a pioneer factor or chromatin modulator. Demonstrating pioneer function typically requires direct evidence of chromatin opening or binding to closed chromatin regions (e.g., ATAC-seq, nucleosome occupancy assays). I recommend revising this statement or providing supporting evidence.

We agree that the fact that GRHL2 interacts with chromatin remodelers does not by itself prove that GRHL2 acts as a pioneer factor or chromatin modulator. However, a previous study (Jacobs et al, Nature genetics, 2018) has shown directly that the GRHL family members (including GRHL2) have pioneering function and regulate the accessibility of enhancers. We adapted line 140-141 to state this more clearly. In addition, our newly added data in Figure 2G also support the fact that GRHL2 has a role in regulating chromatin accessibility in T47D cells.

R2.7 The pulldown Western blot lacks an IgG control in panel D.

This is correct. As the co-IP in Figure 1D served as a validation of the RIME and was specifically aimed at determining the effect of hormone treatment on the observed PR/GRHL2 interaction, we did not perform this control given the scale of the experiment. However, during RIME optimization, we performed GRHL2 staining of the IgG controls by western blot, shown in figure 2 for the reviewer below. As stated above, some background GRHL2 signal was observed in the IgG samples, but a clear enrichment is seen in the GRHL2 IP.

Taken together, we believe that the well-controlled RIME, combined with the co-IP presented, provides strong evidence that the observed signal reflects a genuine GRHL-PR interaction.

Figure 2 for reviewer: WB of input and IP GRHL2 and IgG RIME samples stained for GRHL2. NT = non-treated, T = treated

R2.8 Depending on the journal and target audience, it may be helpful to briefly explain what R5020 is at its first mention (line 146).

Thank you. We have adapted this accordingly.

R2.9 The authors state that three technical replicates were performed for each experimental condition. It would be helpful to clarify the expected level of overlap between biological replicates of RIME experiments. This clarification is necessary, especially given the focus on uniquely enriched proteins in untreated versus treated cells, and the observation that some identified proteins in specific conditions are not chromatin-associated. Replicates or validations would strengthen the findings.

We use the term technical rather than biological replicates because for cell lines, defining true biological replicates is challenging, as most variability arises from experimental rather than biological differences. To introduce some variation, we split our T47DS cells into three parallel dishes 5 days prior to starting the treatment. We purposely did this, to minimize to minimize the likelihood that proteins identified as uniquely enriched are artifacts. Each of the three technical replicates comes from one of these three parallel splits (so equal passage numbers but propagated in parallel dishes for 5 days before the start of the experiment).

To generate the three technical replicates for our RIME, we plated cells from the parallel grown splits. Treatments for the three replicates were performed per replicate. Samples were crosslinked, harvested and lysed for subsequent RIME analysis, the three replicates were processed in parallel, for technical and logistical reasons. To clarify the experimental setup, we have updated the methods section accordingly (lines 566-568).

As for the detection of non-chromatin-associated proteins: We cannot rule out that these are artifacts, as they may arise from residual cytosolic lysate during nuclear extraction. Alternatively, they could reflect a more dynamic subcellular localization of these proteins than currently annotated or appreciated.

R2.10 The volcano plot for the RIME experiment appears to show three distinct clusters of proteins on the right, which is unusual for this type of analysis. The presence of these apparent groupings may suggest an artifact from the data processing, such as imputation. Can the authors clarify the origin of these groupings? If it is due to imputation or missing values, I recommend applying a stricter threshold, such as requiring detection in all three replicates (3/3) to improve the robustness of the enrichment analysis and increase confidence in the identified interactors.

We thank the reviewer for pointing this out. As suggested, we re-evaluated the imputation and applied a stricter threshold, requiring detection in all three replicates. Indeed, the separate clusters were due to missing values, therefore we now revised the imputation method by imputing values based on the normal distribution. Using this revised analysis, we identify 2352 GRHL2 interactors instead of 1140, but the number of interacting proteins annotated as transcription factors or chromatin-associated/modifying proteins was still 103. Figure 1B, 1E, and Supplementary Figure 4A have been updated accordingly. We also revised the methods section to reflect this change. We think this suggestion has improved our analysis of the data and we thank the reviewer for pointing this out.

R2.11 The statement that "PR and GRHL2 frequently overlap" may be overstated given that only ~700 overlapping sites are reported (cut&run).

We have replaced "frequently overlap" by "can overlap" (line 229-230).

R2.12 The model in Figure 6 suggests limited chromatin occupancy of PR and GRHL2 in hormone-depleted conditions, consistent with the known requirement of ligand for stable PR-DNA binding. However, Figure 1 shows no major difference in GRHL2-PR interaction between untreated and hormone-treated cells. This raises questions about where and how this interaction occurs in the absence of hormone. Since PR binding to chromatin is typically minimal without ligand, can the authors clarify this given that RIME data reflect chromatin-bound interactions.

Indeed, the model in figure 6 suggests limited chromatin occupancy of PR and GRHL2 under hormone-depleted conditions. It is, however, important to note that the locus shown represents a gene regulated by both PR and GRHL2 - and not just any gene. We recognize that this was not sufficiently clear in the original version, and we have now clarified this in both the main text (line 331-334) and the figure legend.

We propose that PR and GRHL2 bind or become enriched at enhancer sites associated with their target genes upon ligand stimulation. This is consistent with the known requirement of ligand for stable PR-DNA binding and with our observation that PR/GRHL2 overlapping peaks are detected only in the ligand-treated condition of the CUT&RUN experiment. Given the broader role of GRHL2, it also binds chromatin independently of progesterone and the progesterone receptor, which is why we included-but did not focus on-GRHL2-only binding events in our model.

We would also like to clarify that, although RIME includes a nuclear enrichment step that enriches for chromatin-associated proteins, the pulldown is performed on nuclear lysates. Therefore, it captures both chromatin-bound protein complexes and freely soluble nuclear complexes, which unfortunately cannot be distinguished. GRHL2 is well established as a nuclear protein (Zeng et al., Cancers 2024; Riethdorf et al., International Journal of Cancer 2015), and although PR is classically described as translocating to the nucleus upon hormone stimulation, several studies-including our own-have shown that PR is continuously present in the nucleus (Aarts et al., J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 2023; Frigo et al., Essays Biochem. 2021).

We therefore propose that PR and GRHL2 may already interact in the nucleus without directly binding to chromatin. Given our observation that GRHL2 binding sites on the chromatin are redistributed upon R5020 mediated signaling activation, we hypothesize that such pre-formed PR-GRHL2 nuclear complexes may assist the rapid recruitment of GRHL2 to progesterone-responsive chromatin regions.

We have expanded the discussion to include a dedicated section addressing this point (line 376-388).

R2.13 It would be of interest to assess the overlap between the proteins identified in the RIME experiment and the motif analysis results.

In the discussion section of our original manuscript, we highlighted some overlapping proteins in the RIME and motif analysis, including STAT6 and FOXA1. However, we had not yet systematically analyzed overlap in both analyses. To address this, we now compared all enriched motifs (so not only the top 5 as displayed in our figures) under GRHL2, PR, and GRHL2/PR shared sites from both the CUT&RUN and ChIP-seq datasets with the proteins identified as GRHL2 interactors in our RIME. Although we identified numerous GRHL2-associated proteins, relatively few of them were transcription factors whose binding motifs were also enriched under GRHL2 peaks.

In our revised manuscript we have added a section in the discussion highlighting our systematic overlap of the results of our RIME experiment and the motif enrichment of the ChIP-seq and CUT&RUN analysis (line 415-436).

R2.14 The authors chose CUT&RUN to assess chromatin binding of PR and GRHL2. Given that RIME is also based on chromatin immunoprecipitation - ChIP protocol, it would be helpful to clarify why CUT&RUN was selected over ChIP-seq for the DNA-binding assays. What is the overlap with published data?

As also mentioned in our response to R1.3 and R1.5, we deliberately chose the CUT&RUN approach to minimize artifacts introduced by crosslinking and sonication, thereby reducing background and allowing the identification of high-confidence, direct DNA-binding events. Since GRHL2 physically interacts with PR, ChIP-seq could potentially capture indirect binding of GRHL2 at PR-bound sites (and vice versa). In contrast, CUT&RUN primarily detects direct DNA-protein interactions, providing a more specific and accurate binding profile. Additionally, CUT&RUN serves as an independent validation method for data obtained using ChIP-like protocols.

Since CUT&RUN, similar to ChIP, can show limited reproducibility (Nordin et al., Nucleic Acids Research, 2024), and to our knowledge few PR CUT&RUN and no GRHL2 CUT&RUN datasets are currently available, it is challenging to directly compare our data with published datasets. Nevertheless, studies performing PR or ER CUT&RUN (Gillis et al., Cancer Research, 2024; Reese et al., Molecular and Cellular Biology, 2022) report a comparable number of peaks-in the same range of thousands-as observed in our data.

This suggests that a single CUT&RUN experiment in general may detect fewer events than a single ChIP-seq experiment, but that the peaks that are found are likely to reflect direct binding events.

Reviewer #2 (Significance (Required)):

General Assessment:

This study investigates the role of the transcription factor GRHL2 in modulating PR function, using RIME and CUT&RUN to explore protein-protein and protein-chromatin interactions. GRHL2 have been implicated in epithelial biology and transcriptional regulation and interaction with steroid hormone receptors has been reported. This study extends the field by showing a functional link between GRHL2 and PR, which has implications for understanding hormone-dependent gene regulation.

The research will primarily interest a specialized audience in transcriptional regulation, chromatin biology, and hormone receptor signaling.

Key words for this reviewer: chromatin biology, transcription factor function, epigenomics, and proteomics.

We agree that with our implemented changes, this study should reach (and appeal to) an audience interested in transcriptional regulation, chromatin biology, hormone receptor signaling and breast cancer.

Reviewer #3 (Evidence, reproducibility and clarity (Required)):

This study explores the important transcriptional coordination role of Grainyhead-like 2 (GRHL2) on the transcriptional regulatory function of progesterone receptor (PR). In this paper, the authors start with their recruitment characteristics, take into account their regulatory effects on downstream genes and their effects on the occurrence and development of breast cancer, and further clarify the coordination between them in three-dimensional space. The interaction between GRHL2 and PR, and the subsequent important influence on the co-regulated genes by GRHL2 and PR are analyzed. The overall framework of this study is mainly by RNA seq and CUT-TAG analysis, the molecular mechanism underlying the association between GRHL2 and PR and regulation function of two proteins in breast cancer is not clearly clarified. Some details need to be further improved:

Major comments:

R3.1 For Fig.1D, the molecular weight of each protein should be marked in the diagram, and the expression of GRHL2 in the input group should be supplemented.

We apologize for not including molecular weights in our initial submission. We are not entirely clear what the reviewer means with their statement that "the expression of GRHL2 in the input group should be supplemented". The blot depicted in Figure 1D shows both the input signal and the IP. For the reviewer's information, the full Western blot is depicted below.

Figure 3 for reviewer: Full WBs of input and IP GRHL2 samples stained for GRHL2 or PR. NT = non-treated, T = treated

R3.2 In Fig.2B and Fig 5C, it should be describe well whether GRHL2 recruitment is in the absence or presence of R5020? How about the co-occupancy of PR and GRHL2 region, Promoter or enhancer region? It would be better to show histone marks such as H3K27ac and H3K4me1 to annotate the enhancer region.

As also stated in our response to R1.3, we acknowledge that the ChIP-seq experiments cannot definitively determine whether GRHL2 and PR co-occupy genomic regions under ligand-stimulated conditions, since the GRHL2 dataset was generated in the absence of progesterone stimulation (as indicated in lines 167-169). To clarify this, we have now specified this detail in the legend of figure 2 by noting "untreated GRHL2 ChIP." To directly assess GRHL2 chromatin binding under progesterone-stimulated conditions, we performed CUT&RUN experiments for both GRHL2 and PR under untreated and R5020-treated conditions. These experiments revealed a subset of overlapping PR and GRHL2 binding sites (approximately 5% of all identified PR peaks.

In our original manuscript, we performed genomic annotation of the GRHL2, PR, and GRHL2/PR overlapping peaks (Figure 2E) and found that most of these sites were located in intergenic regions, where enhancers are typically found, with ~20% located in promoter regions. We appreciate the reviewer's suggestion to further overlap the ChIP-seq peaks with histone marks such as H3K27ac and H3K4me1. We have now incorporated publicly available ATAC-seq and H3K27ac ChIP datasets in our revised manuscript (as also suggested by Reviewer 1) and find that shared GRHL2/PR sites are indeed located in active enhancer regions marked by H3K27ac (see Figure 2F). Additionally, as expected, we find that GRHL2/PR overlapping sites are enriched at open chromatin (Figure 2G).

R3.3 What is the biological function analysis by KEGG or GO analysis for the overlapping genes from VN plots of RNA-seq with CUT-TAG peaks. The genes co-regulated by GRH2L and PR are further determined.

For us, it is not entirely clear what reviewer 3 is asking here, but we can explain the following: as it is challenging to integrate HiChIP with CUT&RUN, due to the fundamentally different nature of the two techniques, we chose not to directly assign genes to CUT&RUN peaks. However, we did carefully link the GRHL2, PR, and GRHL2/PR ChIP-seq peaks to their target genes by integrating chromatin looping data from a PR HiChIP analysis. The result from this analysis is depicted in Figure 4B.

As suggested by this reviewer, we also performed a GO-term analysis on the 79 genes that are regulated by both GRHL2 and PR (we now have 79 genes after the re-analysis as suggested in R1.6). The corresponding results are provided for the reviewer in figure 3 of this rebuttal (below). As this additional analysis does not provide further biological insight beyond what is already presented in Figure 4C, we decided to not include this figure in the manuscript.

Figure 4 for reviewer: GO-term analysis on the 79 GRHL2-PR co-regulated genes that are transcriptionally regulated by GRHL2 and PR and that also harbor a PR HiChIP loop anchor at or near their TSS

R3.4 Western blotting should be performed to determine the protein levels of downstream genes co-regulated genes by GRH2L and PR in the absence or presence of R5020.

We agree that determining the response of co-regulated is important. Therefore, in Figure 4D, we present three representative examples of genes that are directly co-regulated by GRHL2 and PR-specifically, genes that are differentially expressed after 4 hours of R5020 exposure. Although protein levels of the targets are of functional importance, GRHL2 and PR are of transcription factors whose immediate effects are primarily exerted at the level of gene transcription. Therefore, in our opinion, changes in mRNA abundance provide the most direct and mechanistically relevant readout of their regulatory activity.

R3.5 The author mentioned that this study positions that GRHL2 acts as a crucial modulator of steroid hormone receptor function, while the authors do not provide the evidences that how does GRHL2 regulate PR-mediated transactivation, and how about these two proteins subcellular distribution in breast cancer cells.

We agree that while our RNA-seq data demonstrate that GRHL2 modulates the expression of PR target genes, and our CUT&RUN experiments show that GRHL2 chromatin binding is reshaped upon R5020 exposure, we have not yet further dissected the molecular mechanism by which GRHL2 functions as a PR co-regulator.

As also mentioned in our response to R1.2, we did consider several follow-up experiments to address this, including PR CUT&RUN in GRHL2 knockdown cells, CUT&RUN for known co-activators such as KMT2C/D and P300, as well as functional studies involving GRHL2 TAD and DBD mutants. However, due to technical and logistical challenges, we were unable to carry out these experiments within the timeframe of this study.

That said, we fully recognize that such approaches would provide deeper mechanistic insight into the interplay between PR and GRHL2. We have therefore explicitly acknowledged this limitation in our limitations of the study section (lines 502-507) and consider it an important avenue for future investigation.

Regarding the subcellular distribution in breast cancer cells: As also mentioned in our response to R2.12, GRHL2 is well established as a nuclear protein (Zeng et al., Cancers 2024; Riethdorf et al., International Journal of Cancer 2015), and although PR is classically described as translocating to the nucleus upon hormone stimulation, several studies-including our own-have shown that PR is continuously present in the nucleus (Aarts et al., J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 2023; Frigo et al., Essays Biochem. 2021). Thus, both proteins mostly reside in the nucleus in breast (cancer) cells both in the absence and presence of hormone stimulation, but dynamic subcellular shuttling is likely to occur.

Minor comments:

Please describe in more detail the relationship between PR and GRHL2 binding independent of the hormone in the discussion section.

As also mentioned in our response to R2.12, we have expanded the discussion to include a dedicated section addressing this point (lines 376-388).

Reviewer #3 (Significance (Required)):

Advance: Compare the study to existing published knowledge, it fills a gap. The authors provide RNA seq and CUT-TAG sequence analysis to show the recruitment of GRHL2 and PR and the co-regulated genes in the absence or presence of progesterone.

Audience: breast surgery will be interested, and the audiences will cover clinical and basic research.

My expertise is focused on the epigenetic modulation of steroid hormone receptors in the related cancers, such as breast cancer, prostate cancer, and endometrial carcinoma.

We agree that with our implemented changes, this study should reach (and appeal to) an audience interested in transcriptional regulation, chromatin biology, hormone receptor signaling and breast cancer.