Edge Effects

It was in the Design Science Studio that I learned about edge effects.

Yesterday, I was thinking about how my life embodies the concept of edge effects. That same day, a book was delivered to our door, Design for the Real World by Victor Papanek.

Today, I was reading these words:

Design for the Real World

Design for Survival and Survival through Design: A Summation

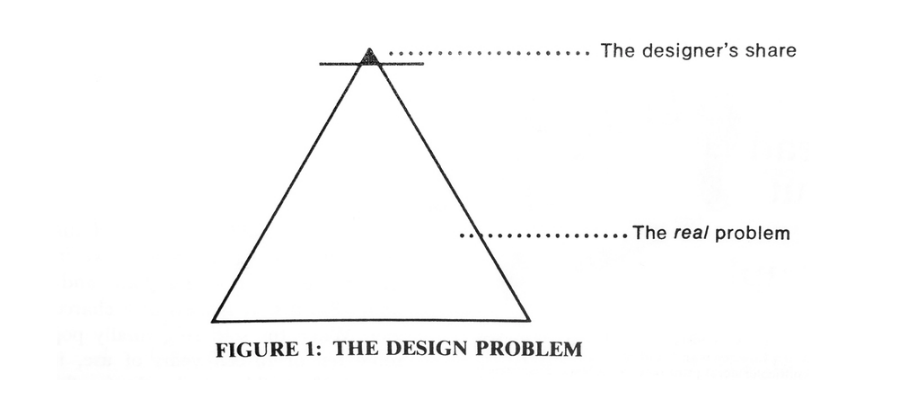

Integrated, comprehensive, anticipatory design is the act of planning and shaping carried on across the various disciplines, an act continuously carried on at interfaces between them.

Victor Papanek goes on to say:

It is at the border of different techniques or disciplines that most new discoveries are made and most action is inaugurated. It is when two differing areas of knowledge are brought into contact with one another that… a new science may come into being.

(Page 323)

Exiles and Emigrés

The Bauhaus spread its ideas because it existed at the boundaries, the avant-garde, the edges of what was thought to be possible, especially as a socialist utopian idea found its way to a capitalist industrial-military complex, where the concept of modernism was co-opted and colonized by globalizing economic forces beyond the control of the individual. Design was the virus that propagated around the world through the vehicle of corporate globalization.

That same design ethic is infecting corporations with a conscience, with empathy, with a process that begins with listening to people. Design is the virus that can spread the values of unconditional love throughout the body of neoliberal capitalism.