Such boundary objects play a brokering role involving translation, coordination, and alignment among the perspectives of different communities coming together in a kind of meta-community [26], which is the case in our fractalized community networks.

- Sep 2021

-

www.mdpi.com www.mdpi.com

-

-

boundary objects

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

- Jan 2019

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

hus, we believe challenges occur in all three indica-tors of the level of development of a TMS—expertisespecialization, credibility, and expertise coordination—requiring a need to consider extending theorizing abouteach indicator for emergent response groups.

Ways to extend TMS to emergent groups:

"1. Reconceptualize the Role of Expertise Specialization as a Basis for Task Assignment"

"2. Assessing Credibility in Emergent Response Groups"

"3. Expertise Coordination in Emergent Response Groups"

These extensions evoke boundary objects and invisibility

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

third response to manage tensions is to promoteknowledge collaboration by enacting dynamic bound-aries. In social sciences, although boundaries divide anddisintegrate collectives, they also coordinate and inte-grate social action (Bowker and Star 1999, Lamont andMolnár 2002). Fluidity brings the need for flexible andpermeable boundaries, but it is not only the propertiesof the boundaries but also their dynamicity that helpmanage tensions.

Cites Bowker and Star

Good examples of how boundaries co-evolve and take on new meanings follow this paragraph.

-

Based on our collective research on to date, we haveidentified that as tensions ebb and flow, OCs use (or,more precisely, participants engage in) any of the fourtypes of responses that seem to help the OC be gen-erative. The first generative response is labeledEngen-dering Roles in the Moment. In this response, membersenact specific roles that help turn the potentially negativeconsequences of a tension into positive consequences.The second generative response is labeledChannelingParticipation. In this response, members create a nar-rative that helps keep fluid participants informed ofthe state of the knowledge, with this narrative havinga necessary duality between a front narrative for gen-eral public consumption and a back narrative to airthe differences and emotions created by the tensions.The third generative response is labeledDynamicallyChanging Boundaries. In this response, OCs changetheir boundaries in ways that discourage or encouragecertain resources into and out of the communities at cer-tain times, depending on the nature of the tension. Thefourth generative response is labeledEvolving Technol-ogy Affordances. In this response, OCs iteratively evolvetheir technologies in use in ways that are embedded by,and become embedded into, iteratively enhanced socialnorms. These iterations help the OC to socially and tech-nically automate responses to tensions so that the com-munity does not unravel.

Productive responses to experienced tensions.

Evokes boundary objects (dynamically changing boundaries) and design affordances/heuristics (evolving technology affordances)

-

Fluidity recognizes the highly flexible or permeableboundaries of OCs, where it is hard to figure out whois in the community and who is outside (Preece et al.2004) at any point in time, let alone over time. Theyare adaptive in that they change as the attention, actions,and interests of the collective of participants change overtime. Many individuals in an OC are at various stagesof exit and entry that change fluidly over time.

Evokes boundary objects and boundary infrastructures.

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

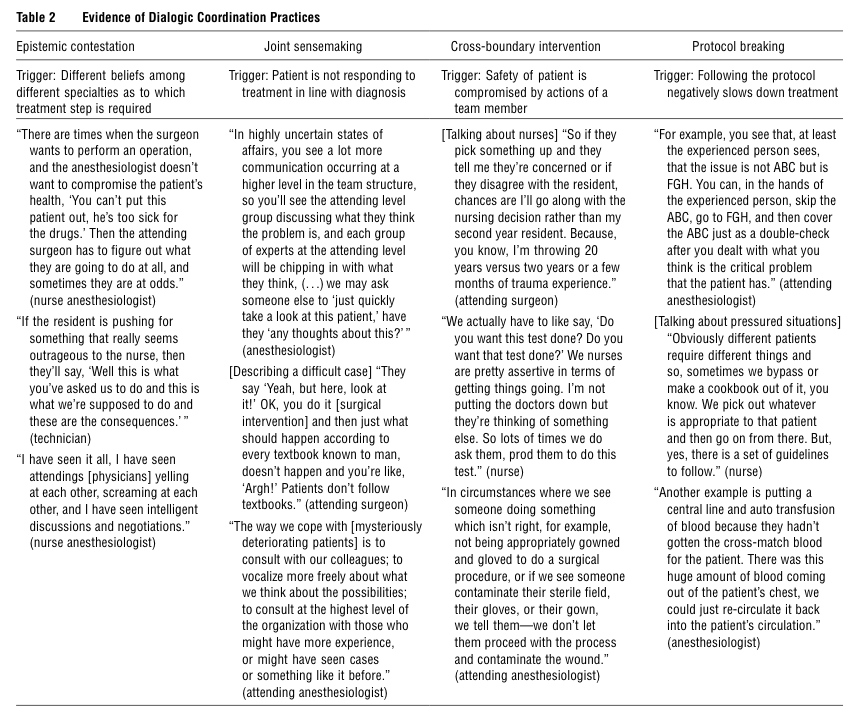

Recently, Brown and Duguid (2001, p. 208) sug-gested that coordination of organizational knowledgeis likely to be more challenging than coordination ofroutine work, principally because the “elements to becoordinated are not just individuals but communitiesand the practices they foster.” As we found in ourinvestigation of coordination at the boundary, signif-icant epistemic differences exist and must be recog-nized. As the dialogic practices enacted in responseto problematic trajectories show, the epistemic dif-ferences reflect different perspectives or prioritiesand cannot be bridged through better knowledge

Need to think more about how subgroups in SBTF (Core Team/Coords, GIS, locals/diaspora, experienced vols, new vols, etc.) act as communities of practice. How does this influence sensemaking, epistemic decisions, synchronization, contention, negotiation around boundaries, etc.?

-

Boundarywork requires the ability to see perspectives devel-oped by people immersed in a different commu-nity of knowing (Boland and Tenkasi 1995, Star andGriesemer 1989). Often, particular disciplinary focilead to differences in opinion regarding what stepsto take next in treating the patient.

Differences in boundary work can lead to contentiousness.

-

The termdialogic—as opposed to monologic—recognizes dif-ferences and emphasizes the existence of epistemicboundaries, different understandings of events, andthe existence of boundary objects (e.g., the diagnosisor the treatment plan). A dialogic approach to coordi-nation is the recognition that action, communication,and cognition are essentially relational and highlysituated. We use the concept of trajectory (Bourdieu1990, Strauss 1993) to recognize that treatment pro-gressions are not always linear or positive.

Cites Star (boundary objects) and Strauss, Bourdieu (trajectory)

-

In knowledge work, several related factors sug-gest the need to reconceptualize coordination.

Complex knowledge work coordination demands attention to how coordination is managed, as well as what (content) and when (temporality).

"This distinction becomes increasingly important in complex knowledge work where there is less reliance on formal structure, interdependence is changing, and work is primarily performed in teams."

Traditional theories of coordination are not entirely relevant to fast-response teams who are more flexible, less formally configured and use more improvised decision making mechanisms.

These more flexible groups also are more multi-disciplinary communities of practice with different epistemic standards, work practices, and contexts.

"Thus, because of differences in perspectives and interests, it becomes necessary to provide support for cross-boundary knowledge transformation (Carlile 2002)."

Evokes boundary objects/boundary infrastructure issues.

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

signifies a new epistemology insofar as it portraysevents as discrete and isolated; knowledges as mod-ifiable, categorizable, and abstractable; and locally-situated knowledges as best understood by thoseworking remotely

Evokes complexity of creating classifications and boundary objects that can provide relational data, e.g., report of fire and report of car bombing.

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

. Previously, scholars have generally ignored any notion of time. Now, we need to make explicit our use of time in understanding disaster. Such an application, I believe, will give us a much deeper understanding on defining disaster, how and why such events unfold, and how various social entities attempt to return to normal after the event. Finally, the use of social time in disaster can provide sociologists a deeper look into understanding key theoretical issues related to social order, social change and social emergence, along with voluntaristic versus deterministic patterns of behavior among various units of analysis.

Scarcity of temporal considerations in previous work.

Connects sociotemporal experiences and enactment of time to social order, social change, volunteer behavior and new units of analysis.

Here's my central thesis.

-

the field. Such a fresh approach possibly improves a wide range of conceptual issues in disasters and hazards. In addition, such an approach would give us insights on how disaster managers, emergency responders, and disaster victims (recognizing that these “roles” may overlap in some cases) see, use and experience time. This, in turn, could assist with a number of applied issues (e.g., warning, effective “response,” priorities in “recovery”) throughout the process of disaster.

Neal cites his 1997 paper about the need to develop better categories to describe disaster phases. Here, her attempts to work through those classifications with a sociotemporal bent.

Evokes Bowker and Star's work on classification and boundary objects/infrastructures but also Yakura (2002) on temporal boundary objects.

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

The next logical step to aid analysis would be to cross-tabulate the temporal periods of "before, during, and after" with functional activities. This type of analysis and consideration could be further extended by including both the unit of analysis and various social categories such as social class or ethnicity. This type of three-dimensional approach would also strongly highlight the idea that disaster phases are multilayered. Overall, not only do different groups and units of analysis experience the phases at different times, but that multiple aspects of time (i.e., objective and subjective; before, during, after a disaster) intermesh with specific activities.

Evokes temporal boundary objects and classification alongside feminist and post-colonial HCI approaches.

-

We must differentiate whether the use of any phrase refers to temporal or functional aspects of disaster. They should not have multiple meanings

Sensemaking ia a big problem, especially when it comes to multiple stakeholders involved in a disaster (responders, victims, effected people, policy wonks, legislators, researchers, etc.)

Evokes boundary objects work

-

Second, the manner the field handles the issue of disaster phases actually reflects a larger problem in the field. Specifically, how do we define disaster? Kreps (1984, p. 324) comes closest to recognizing the relationship among disaster phases, the theoretical components of disaster (i.e., social order and social action), and the definition of disaster (primarily in a heading in his paper). Unfortunately, he does not elaborate upon the connection of defining disaster and disaster phases. Thus, recognizing and recasting our notion of disaster phases may actually help the field more precisely understand or define "disaster."

Has this changed since 1997? Cites a passage from Quarantelli that argues disaster research is not well defined.

Evokes Bowker and Star's boundary objects work.

-

Mileti, Drabek, and Haas developed their six categories of: 1) preparedness/adjustment; 2) warning; 3) pre-impact, early actions; 4) post-impact, short-term actions; 5) relief or restoration, and 6) reconstruction. They justify these categories by noting that "Numerous researchers have documented how activities and nonnative definitions appear to vary across time and vary greatly among events" (Mileti, Drabek, Haas 1975, p. 9). The six phases serve as a central component of the authors' codification effort (it organizes the book chapters). Yet, the authors do not provide a more specific definition for each category. Other theoretical underpinnings in the book receive much more detailed justification (e.g., collective stress, social nature of disaster).

An update to Barton and Dyne's work by Mileti, Drabek and Haas continues to give short-shrift to theoretical underpinnings of the classifications, per Neal.

Evokes Bowker and Star's work on classifications.

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

It is boundaries that help us separate one entity from another: "To classify things is to arrange them in groups ... separated by clearly determined lines of demarcation .... At the bottom of our conception of class there is the idea of a circumscription with fixed and definite outlines. "7 Indeed, the word define derives from the Latin word for boundary, which is finis. To define something is to mark its boundaries, 8 to surround it with a mental fence that separates it from everything else. As evidenced by our failure to notice objects that are not clearly differentiated from their surroundings, it is their boundaries that allow us to perceive "things" at all.

Social reality is constructed by defining boundaries and visibility to objects. Evokes Bowker and Star's classification and boundary object framework.

-

es an entity with a distinctive meaning5 as well as with a distinctive identity that sets it apart from everything else. The way we cut up the world clearly affects the way we organ

Zerubavel posits that meaning is made by distinguishing objects/events from one another. These contrasts are further delineated by classification and/or making things invisible.

-

Nonetheless, without some lumping, it would be impossible ever to experience any collectivity, or mental entity for that matter. The ability to ignore the uniqueness of items and regard them as typical members of categories is a prerequisite for classifying any group of phenomena. Such ability to "typify"106 our experience is therefore one of the cornerstones of social reality

Classification is the mechanism for making sense of disparate objects through the process of lumping and making differences invisible.

-

A mental field is basically a cluster of items that are more similar to one another than to any other item. Generating such fields, therefore, usually involves some lumping.

Evokes Bowker and Star's boundary object work re: the mental models of lumping and splitting

-

A frame is characterized not by its contents but rather by the distinctive way in which it transforms the contents' meaning.

How does this square with the definition of "boundary objects"?

-

Temporal differentiation helps substantiate elusive mental distinctions. Like their spatial counterparts, temporal boundaries often represent mental partitions and thus serve to divide more than just time.

Temporal boundaries (and the objects inherent in them) are used to convey additional meaning and context. These partitions are used to describe historical distinctions ("The Great Depression", "Vietnam Era"), life distinctions (work vs private time vs religious observance).

Examples above are from the chapter.

-

In order to endow the things we perceive with meaning, we normally ignore their uniqueness and regard them as typical members of a particular class of objects (a relative, a present), acts (an apology, a crime), or events (a game, a conference).2 After all, "If each of the many things in the world were taken as distinct, unique, a thing in itself unrelated to any other thing, perception of the world would disintegrate into complete meaninglessness. "3 Indeed, things become meaningful only when placed in some category.

Connect this to Bowker and Star (2000) Sorting Things Out.

-

The perception of supposedly insular chunks of space is probably the most fundamental manifestation of how we divide reality into islands of meaning. Examining how we partition space, therefore, is an ideal way to start exploring how we partition our social world

Zerubavel describes how we use space to partition meaning from large, complex or unfamiliar objects.

Evokes the notion of a boundary object.

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

These protocols, formal structures, plans, procedures, and schemes can be con-ceived of asmechanismsin the sense that they (1) are objectified in some way(explicitly stated, represented in material form), and (2) are deterministic or at leastgive reasonably predictable results if applied properly. And they aremechanisms ofinteractionin the sense that they reduce the complexity of articulating cooperativework.

People apply "mechanisms of interaction" to reduce the complexity of the articulation work.

Schmidt and Bannon use these examples:

• Formal and informal organizational structures • Planning and scheduling • Standard operating procedures (see Suchman's work on situated action) • Indexes and classifications for organizational and retrieval (see Bowker and Star on boundary objects/infrastructures)

-

In this section of the paper we broach two aspects of this articulation issue, onefocusing on the management of workflow, the other on the construction and manage-ment of what we term a ‘common information space’. The former concept has beenthe subject of discussion for some time, in the guise of such terms as office automa-tion and more recently, workflow automation. The latter concept has, in our view,been somewhat neglected, despite its critical importance for the accomplishmentof many distributed work activities

A quick scan of ACM library papers that tag "articulation work" seems to indicate the "common information space" problem still has not attracted a lot of study. This could be a good entry point for my work with CSCW because time cuts across both workflow and information space.

Nicely bundles boundary infrastructure, sense-making and distributed work

-

- Dec 2018

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

Resistance Realily is 'that which resists,' according to Latour's (1987) Pragmatistinspired definition. The resistances thal designers and users encounter will change lhc ubiquitous networks of classifications and standards. Although convergence may appear at times to create an inescapable cycle of feedback and verification, the very multiplicity of people, things and processes involved mean lhat they are never locked in for all time.

Questioning the infrastructural inversion via ubiquity, material and texture, history, and power shapes the visibility and invisibility of the infrastructure that society creates for itself.

-

Infrastructure and Method: Convergence These ubiquitous, textured dai;sifications and standards help frame our representation of the past and the sequencing of event� in the present. They (:an best be understood as doing the ever local, ever partial work of making it appear that science describes nature (and nature alone) and that politics is about social power (and social power alone).

"Standards, categories, technologies, and phenomenology are increasingly converging in large-scale information infrastructure." (p. 47)

Convergence gets to how things work out as "scaffolding in the conduct of modern life."

-

Practical Politics �1 ·he fourch major theme is uncovering the practical politics of classifying awl standardizing. 'fhi<; is the de.sign end of the spectrum of investigating categories and standards as technologies. There are two processes associated with these politics: arriving at categories and standards, and, along the way, deciding what will be visible or invisible within the system.

Politics, as in power dynamics, leadership, negotiation, and decision-making authority, play a role in determining how classifications and standards infrastructures are perceived as visible/invisible.

-

The Indeterminacy of the Past: Multiple Times, Multiple Voices The third methodological theme concerns ihe f1asl as indetc,rr,1inate. 10 We are constantly revising our knowledge of the past in light of new developments in the present.

Visibility can be obtained by peeling back the history of the infrastructure -- how it began, how it was added to, how it changed/adapted over time.

Looking back in time also provides an opportunity to consider how different people/perspectives influenced the infrastructure. Who was vocal? Who was silent? Who was silenced?

-

Materiality and Texture The second methodological departure point is that. classifications and standards are material, as well as symbolic.

Another way to make infrastructures visible is to envision their physical presence (materiality) and texture (experience).

Metaphors play an important role here.

-

This categorical saturation furthermore forms a complex web. Although it is possible to pull out a single dassilication scheme or standard for reference purposes, in reality none of them stand alone. So a subproperty of ubiquity is interdependence, ,md frequently, integration. A systems approach might see the proliferation of both standards and classilications as purely a matter of integration-almost like a gigantic web of interoperability. Yet the sheer density of these phenomena go beyond questions of interoperability. They are layered, tangled, textured; they interact lo form an ecology as well as a flat set of compatibilities.

Ubiquitous classifications and standards are also interdependent and integrated, thus creating complex systems that work but the components of which tend to be invisible.

Example: Other classifications when the phenomena/object don't fit elsewhere or the "cumulative mess trajectory" which occurs when categories and standards interact in messy ways

-

Ubiquity The first major theme is the ubiquity of classifying and standardizing. Classification schemes and standards literally saturate our environment.

Methodological themes for infrastructural inversion -- how to make the invisible visible

-

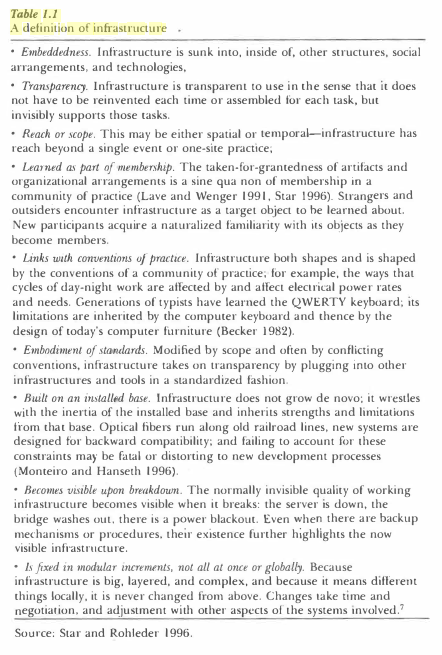

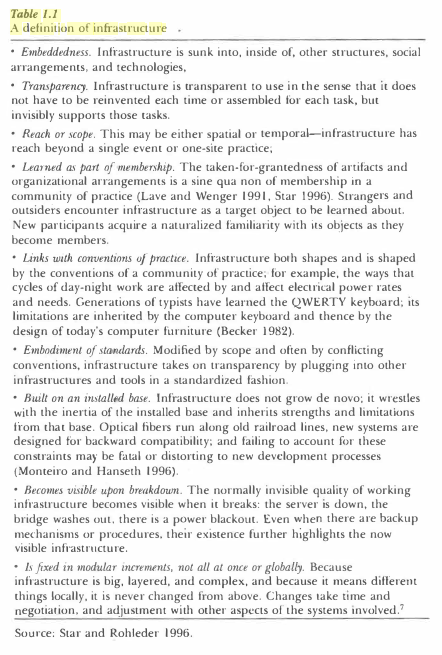

A definition of infrastructure

Definition of infrastructure

-

This chapter offers four themes, methodological points of departure for the analysis of these complex relationships. Each theme operates as a gestalt switch-it comes in the form of an i11fras/:ruclural inversion (Bowker 1994). This inversion is a struggle against the tendency of infrastructure to disappear (except when breaking down). Tt means learning to look closely at technologies and arrangements that, by design and hy habit, tend to fade into the woodwork (sometimes literally!). Infrastructural inversion means recognizing the depths of interdependence of technical networks and standards, on the one hand, and the real work of politics and knowledge production8 on the other.

Definition of infrastructural inversion

How normally invisible structures become visible (gestalt -- whole is perceived as more than the sum of its parts) when there is a breakdown

-

Standards Classifications and standards are closely related, but not identical. \-Vhile this book focuses on classificalion, standards are crucial components of the larger argument. The systems we discuss often do become standardized; in addition, a standard is in part a way of classifying the world. What then are standards? The term as we use it in the book has several dimensions:

Definition of standards

"What are standards?" Cited verbatim from the book

- A set of agreed-upon rules for the production of objects

- Spans more than one community of practice. It has temporal reach since it persists over time.

- Deployed in making things work together over distance and heterogeneous metrics

- Standards are enforced by some legal/regulatory/professional/government body.

- There is no natural law that the best standard wins

- Standards can be difficult and expensive to change

-

Infrastructures are never transparent for everyone, ancl lheir '\\•orkabilit y as they scale up becomes increasingly complex. Through due methodological attention to the architecture and use of these syslems, we can achieve a deeper understanding of how it is that individuals and communities meet infrastructure. ·we know that this means, at Lhe leasl, an understanding of infraslructure that includes these points:

Cited verbatim from book:

- A historical process of development of many tools, arranged for a wide variety of users and made to work in concert

- A practical match among routines of work practice, technology, and wider scale organizational and technical resources

- A rich set of negotiated compromises ranging from epistemology to data entry that are both available and transparent to communities of users

- A negotiated order in which all of the above, recursively, can function together.

-

The sheer density of the collisions of classification schemes in our lives calls for a new kind of science, a new set of metaphors, linking traditional social science and computer and information science. We need a tqpography of things such as the distribution of ambiguity; the fluid dynamics of how classification systems meet up-a plate tectonics rather than a static geology. This nevi science will draw on the best empirical studies of work-arounds, information use, and mundane tools such as desktop folders and file cabinets (perhaps peering backwards out frorn the Web and into the practices). It will also use the best of object-oriented programming and other areas of computer science to describe this territory. It will build on years of valuable research on classification in library and information s<:ience.

"Why it is important to study classification systems"

-

Information infrastrucLUre is a tricky thing to analyze_l; Good, usable systems disappear almost by deiinition. The easier they arc lo use, the harder they are to see.

The invisibility of infrastructure

-

A� we know from studies of work of all sorts, people do not do the ideal joh, but the doable job. \Vhen faced with too many alternatives and too much information, they satisfice (Mard1 and Simon 1958).

Satisficing as a sensemaking strategy

-

Forms like Lhe death certificate, ·when ag6TTcgated, form a case of what Kirk and Kutd1ins (1992) call "the substitution of precision for validity" (see also Star 1989b). That is, when a seemingly neutral data collection mechanism is substituted for ethkal conflict about the contents of the forms, the moral debate is partially erased. One may get ever more prn:ise knowledge, without having resolved deeper questions, and indeed, by burying those questions.

Real dilemma for humanitarian data: "the substitution of precision for validity"

-

we ·define boundary o4_jects as those o�jects that both inhabit several communities of practice and satisfy the informational requirements of each of them. In working practice, tJ1ey are objects that are able both to travel across borders and maintain some sort of constant identity. They can be tailored to meet rhe needs of any one community (they arc plastic.: in this sense, or customizable). At the same time, they have common identities across settings. 'Ibis is achieved by aJlowing the objects to be weakly structured in wmmon use, imposing stronger structures in the individualsite cailored use. They a.re thus both ambiguous and constant; they may be abstract or concrete.

Definition of boundary objects

Description of how boundary objects are structured

-

Classifications may or may not become standardized. If they do not, they are ad hoc, limited to an individual or a local community, and/or of Limited duration. At the same time, every successful standard imposes a classification system, al the very least between good and bad ways of organizing acLions or things. And the work-arounds involved in the practical use of standards frequently entail the use of ad hoc nonstandard categories.

This is an important point for classifying and standardizing modes of time and temporal representations in information systems. What comes first? The class or the standard?

-

Nomenclature and dassifi<:at..ion are frequently confused, howevc1; since attempts are often made to model nomenclature on a 1>ingle, stable system of classification principles, as for example with bot.any (Bowke1; in press) or anatomy.

Nomenclature is an "agreed-upon naming scheme, one that does not follow any classificatory principles."

-

Clas.�ification A classification is a spatial, temporal, or sjH1ti11-lemporal segmm,tation rif lhe world. ,\ "classification system" is a set of boxes (rnelaphorical or literal) inlo which things can be pul to then do some kind of work-bureaucratic or knowledge production. In an abstract, .ideal sense, a classification system exhibits the frillowing properties:

Definition of classification

"A classification system exhibits the following properties:"

- There are consistent, unique classificatory principles in operation

- The categories are mutually exclusive

- The system is complete

-

vVe have a moral and ethical agenda in our querying of these systems. Each standard and each category valorizcs some point of view and silences another. This is not inherently a bad thing-indeed it is inescapable.

Key point here about the power of classification to make objects/phenomena visible or invisible.

In thinking about classifications of time/temporality, what does the standardization of some forms (ISO, commonly accepted terms/metaphors) say about the systems we design to account for time-based information? Is it simply an argument of ease/difficulty in formatting temporal data or is there some other social/cultural issue at play?

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

Table 1.1 A definition of infrastructure

Definition of infrastructure

-

This categorical saturation furthermore forms a complex web. Although it is possible to pull out a single classification scheme or standard for reference purposes, in reality none of them stand alone. So a_ subproperty of ubiquity is interdependence, and frequently, integrat10n. A systems approach might see the proliferation of both standards and classifications as purely a matter of integration-almost like a gigantic web of interoperability. Yet the sheer density of these phenomena go beyond questions of interoperability. They are layered, tangled, textured; they interact to form an ecology as well as a flat set of compatibilities.

Ubiquitous classifications and standards are also interdependent and integrated, thus creating complex systems that tend to be invisible.

Example: Other classifications when the phenomena/object don't fit elsewehre or the "cumulative mess trajectory" which occurs when categories and standards interact in messy ways

-

Ubiquity __ The first major theme is the ubiquity of classifying and standardmng. Classification schemes and standards literally saturate our environment.

Methodological themes for infrastructural inversion -- how to make the invisible visible

-

This chapter offers four themes, methodological points of departure for the analysis of these complex relationships. Each theme operates as a gestalt switch-it comes in the form of an infrastructural inversion (Bowker 1994). This inversion is a struggle against the tendency of infrastructure to disappear (except when breaking down). It means learning to look closely at technologies and arrangements that, by design and by habit, tend to fade into the woodwork (sometimes literally!). Infrastructural inversion means recognizing the depths of interdependence of technical networks and standards, on the one hand, and the real work of politics and knowledge production8 on the other.

Definition of infrastructural inversion

How normally invisible structures become visible (gestalt -- whole is perceived as more than the sum of its parts) when there is a breakdown

-

Infrastructures are never transparent for everyone, and their workability as they scale up becomes increasingly complex. Through due methodological attention to the architecture and use of these systems, we can achieve a deeper understanding of how it is that individuals and communities meet infrastructure. We know that this means, at the least, an understanding of infrastructure that includes these points:

Cited verbatim from book:

• A historical process of development of many tools, arranged for a wide variety of users and made to work in concert • A practical match among routines of work practice, technology, and wider scale organizational and technical resources • A rich set of negotiated compromises ranging from epistemology to data entry that are both available and transparent to communities of users • A negotiated order in which all of the above, recursively, can function together.

-

Information infrastructure is a tricky thing to analyze.6 Good, usable systems disappear almost by definition. The easier they are to use, the harder they are to see. As well, most of the time, the bigger they are, the harder they are to see.

The invisibility of infrastructure

-

The sheer density of the collisions of classification scheme� in_ our liv�s calls for a new kind of science, a new set of metaphors, hnkmg traditional social science and computer and information scien�e. We ne�d a topography of things such as the distribution of ambiguity; the flu_,d dynamics of how classification systems �eet u�-a plate tectomcs rather than a static geology. This new science will draw on the best empirical studies of work-arounds, info�mation use, and �undan_e tools such as desktop folders and file cabmets (perhaps peering backwards out from the Web and into the practices). It will also use th<: best of object-oriented programming and other areas of compute, science to describe this territory. It will build on years of valuablt research on classification in library and information science.

"Why it is important to study classification systems"

-

s we know from studies of work of all sorts, people do not do the ideal job, but the doable job. When faced with too many alternatives and too much information, they satisfice (March and Simon 1958).

Satisficing as a sensemaking strategy

-

Forms like the death certificate, when aggregated, form a case of what Kirk and Kutch ins ( 1992) call "the substitution of precision for validity" (see also Star 1989b). That is, when a seemingly neutral data collection mechanism is substituted for ethical conflict about the contents of the forms, the moral debate is partially erased. One may get ever more precise knowledge, without having resolved deeper questions, and indeed, by burying those questions.

Real dilemma for humanitarian data: "the substitution of precision for validity"

-

we define boundary objects as those objects that both inhabit several communities of practice and satis� the informational requirements of each of them. In working practice, they are objects that are able both to travel across borders and maintain some sort of constant identity. They can be tailored to meet the needs of any one community (they are plastic in this sense, or customizable). At the same time, they have common identities across settin�s. This is achieved by allowing the objects to be weakly structured m common use, imposing stronger structures in the individualsite tailored use. They are thus both ambiguous and constant; they may be abstract or concrete.

Definition of boundary objects

Description of how boundary objects are structured

-

Classifications may or may not become standardized. If they do not, they are ad hoc, limited to an individual or a local community, and/or of limited duration. At the same time, every successful standard imposes a classification system, at the very least between good and bad ways of organizing actions or things. And the work-arounds involved in the practical use of standards frequently entail the use of ad hoc nonstandard categories.

This is an important point for classifying and standardizing modes of time and temporal representations in information systems. What comes first? The class or the standard?

-

Standards Classifications and standards are closely related, but not identical. While this book focuses on classification, standards are crucial components of the larger argument. The systems we discuss often do become standardized; in addition, a standard is in part a way of classifying the world.

Definition of standards

"What are standards?"

- A set of agreed-upon rules for the production of objects

- Spans more than one community of practice. It has temporal reach since it persists over time.

- Deployed in making things work together over distance and heterogeneous metrics

- Standards are enforced by some legal/regulatory/professional/government body.

- There is no natural law that the best standard wins

- Standards can be difficult and expensive to change

-

Nomenclature and classification are frequently confused, however, since attempts are often made to model nomenclature on a single, stable system of classification principles,

Nomenclature is an "agreed-upon naming scheme, one that does not follow any classificatory principles."

-

Classification A classification is a spatial, temporal, or spatio-temporal segmentation of the world. A "classification system" is a set of boxes (metaphorical or literal) into which things can be put to then do some kind of work-bureaucratic 9r knowledge production.

Definition of classification

"A classification system exhibits the following properties:"

- There are consistent, unique classificatory principles in operation

- The categories are mutually exclusive

- The system is complete

-

We have a moral and ethical agenda in our querying of these systems. Each standard and each category valorizes some point of view and silences another.

Key point here about the power of classification to make objects/phenomena visible or invisible.

In thinking about classifications of time/temporality, what does the standardization of some forms (ISO, commonly accepted terms/metaphors) say about the systems we design to account for time-based information? Is it simply an argument of ease/difficulty in formatting temporal data or is there some other social/cultural issue at play?

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

Members of organizations sometimes have differing (and multiple)goals, and conflict may be as important as cooperation in obtaining is-sue resolutions (Kling, 1991). Groups and organizations may not haveshared goals, knowledge, meanings, and histories (Heath & Luff,1996; Star & Ruhleder, 1994).

A lot to unpack here as this bullet gets at the fundamental need for boundary objects (Star's work) to traverse sense-making, meanings, motives, and goals within artifacts.

-