More than that, if Hayek is right about a particular level of complexity being unable to understand its own or a higher level of complexity, it would be impossible to understand the nature of sociotemporality in the first place.

- Aug 2021

-

zatavu.blogspot.com zatavu.blogspot.com

-

-

sci-hub.se sci-hub.se

- Jan 2019

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

Based on a practice view, we suggest the followingdefinition ofcoordination: a temporally unfolding andcontextualized process of input regulation and inter-action articulation to realize a collective performance.

Faraj and Xiao offer two important points: Context and trajectories "First, the definition emphasizes the temporal unfolding and contextually situated nature of work processes. It recognizes that coordinated actions are enacted within a specific context, among a specific set of actors, and following a history of previous actions and interactions that necessarily constrain future action."

"Second, following Strauss (1993), we emphasize trajectories to describe sequences of actions toward a goal with an emphasis on contingencies and interactions among actors. Trajectories differ from routines in their emphasis on progression toward a goal and attention to deviation from that goal. Routines merely emphasize sequences of steps and, thus, are difficult to specify in work situations characterized by novelty, unpredictability, and ever-changing combinations of tasks, actors, and resources. Trajectories emphasize both the unfolding of action as well as the interactions that shape it. A trajectory-centric view of coordination recognizes the stochastic aspect of unfolding events and the possibility that combinations of inputs or interactions can lead to trajectories with dreadful outcomes—the Apollo 13 “Houston, we have a problem” scenario. In such moments, coordination is more about dealing with the “situation” than about formal organizational arrangements."

-

Theprimarygoalispatientstabilizationandini-tiating atreatment trajectory—a temporally unfolding

Full quote (page break)

"The primary goal is patient stabilization and initiating a treatment trajectory—a temporally unfolding sequence of events, actions, and interactions—aimed at ensuring patient medical recovery"

Knowledge trajectory is a good description of SBTF's work product/goal

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

. Previously, scholars have generally ignored any notion of time. Now, we need to make explicit our use of time in understanding disaster. Such an application, I believe, will give us a much deeper understanding on defining disaster, how and why such events unfold, and how various social entities attempt to return to normal after the event. Finally, the use of social time in disaster can provide sociologists a deeper look into understanding key theoretical issues related to social order, social change and social emergence, along with voluntaristic versus deterministic patterns of behavior among various units of analysis.

Scarcity of temporal considerations in previous work.

Connects sociotemporal experiences and enactment of time to social order, social change, volunteer behavior and new units of analysis.

Here's my central thesis.

-

the field. Such a fresh approach possibly improves a wide range of conceptual issues in disasters and hazards. In addition, such an approach would give us insights on how disaster managers, emergency responders, and disaster victims (recognizing that these “roles” may overlap in some cases) see, use and experience time. This, in turn, could assist with a number of applied issues (e.g., warning, effective “response,” priorities in “recovery”) throughout the process of disaster.

Neal cites his 1997 paper about the need to develop better categories to describe disaster phases. Here, her attempts to work through those classifications with a sociotemporal bent.

Evokes Bowker and Star's work on classification and boundary objects/infrastructures but also Yakura (2002) on temporal boundary objects.

-

Second, I believe that the concept of entrainment could open new doors for understanding post-impact behavior, or the transition from post-impact to pre-impact (or everyday) behavi

Neal argues that the temporal concept of entrainment (two things synchronizng their pace) can help to differentiate another long-standing critique of disaster research -- the different disaster phase impacts on individuals and sub-groups over time. This gets at his concern (see also Brenda Phillips' work) for feminist, post-colonial and critical theory perspectives on the study of disaster and social change.

Here, Neal posits that returning to pre-impact social rhythms could be a better measure of social change catalyzed by a disaster.

"Rather than using economic, demographic, familial or other measures of social change, entrainment could be a key measure in understanding social change and disaster."

-

The use of social time may also give us a unique view on understanding slow moving disasters (e.g., environmental events, famines and droughts) when compared to sudden impact events. Social time and social disruption provides tools to define disaster without making assessments (i.e., good/bad) of the event.

Neal also contends that time embedded in the disaster onset (sudden vs slow) is a better heuristic for studying these events.

-

In this paper I have shown that the application of social time and social disruption to disaster settings (i.e., pre-impact, impact, post-impact) along can provide a unique way to understand disasters. First, by integrating the ideas of event time, social time, and social disruption, we can develop a foundation for creating an empirically based continuum of everyday life/emergency, disaster, and catastrophe. An implication of this approach is that we use specific social criteria (based upon social disruption via the various time concepts) to define the event. As a result, drawing upon social time and social disruption casts a rather wide net in understanding events what we call disa

Principally, Neal's argument is embedded in his long-standing critique that the language of disaster research and emergency response practice is not precise enough and thus the disaster phases framework is flawed.

Here, he attempts to re-characterize the disaster phases as sociotemporal constructions about events (pre-impact, impact, and post-impact).

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

Disasters might be one of the few natural events that override the socio-temporal order; indeed, damage to the routines of social life is a defining characteristic that separates disasters from local emergencies and other disruption

Evokes Zerubavel and temporal ordering

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

n particular, we note how recent extensions to Activity Theory have addressed theoretical shortcomings similar to our five challenges and suggest directions for bridging the gap between everyday practice and systems support

theoretical base for the case study.

Tie this back to HCC readings/critiques by Halverson and Hutchins on distributed cognition.

-

These extensions increase the complexity of the Activity Theory model but also help to explain tensions present in real-world systems such as when one agent plays different roles in two systems that have divergent goals. Furthermore, this approach provides Activity Theory with a similar degree of agility in representing complex, distributed cognition as competing theoretical approaches, such as Distributed Cognition (Hutchins, 1995).

flexibility of Activity Theory over DCog

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

The manner in which we isolate supposedly discrete "figures" from their surrounding "ground" is also manifested in the way we come to experience ourselves. 52 It involves a form of mental differentiation that entails a fundamental distinction between us and the rest of the world. It is known as our sense of identity.

Evokes Csikszentmihalyi and Rochberg-Halton on developing a sense of self.

-

It is boundaries that help us separate one entity from another: "To classify things is to arrange them in groups ... separated by clearly determined lines of demarcation .... At the bottom of our conception of class there is the idea of a circumscription with fixed and definite outlines. "7 Indeed, the word define derives from the Latin word for boundary, which is finis. To define something is to mark its boundaries, 8 to surround it with a mental fence that separates it from everything else. As evidenced by our failure to notice objects that are not clearly differentiated from their surroundings, it is their boundaries that allow us to perceive "things" at all.

Social reality is constructed by defining boundaries and visibility to objects. Evokes Bowker and Star's classification and boundary object framework.

-

es an entity with a distinctive meaning5 as well as with a distinctive identity that sets it apart from everything else. The way we cut up the world clearly affects the way we organ

Zerubavel posits that meaning is made by distinguishing objects/events from one another. These contrasts are further delineated by classification and/or making things invisible.

-

The need to substantiate the way we segment time into discrete blocks also accounts for the holidays we create to commemorate critical transition points between historical epochs 112 as well as for the rituals we design to articulate significant changes in our relative access to one another-greetings, first kisses, farewell parties, bedtime stories. 113

Rituals also have temporal qualities that help to make sense of socially constructed times/events.

-

Most of the fine lines that separate mental entities from one another are drawn only in our own head and, therefore, totally invisible. And yet, by playing up the act of "crossing" them, we can make mental discontinuities more "tangible." Many rituals, indeed, are designed specifically to substantiate the mental segmentation of reality into discrete chunks. In articulating our "passage" through the mental partitions separating these chunks from one another, such rituals, originally identified by Arnold Van Gennep as "rites of passage,"107 certainly enhance our experience of discontinuity.

Rituals help connect the frame to the spatial qualities of the mental models we create to understand complex ideas.

-

Nonetheless, without some lumping, it would be impossible ever to experience any collectivity, or mental entity for that matter. The ability to ignore the uniqueness of items and regard them as typical members of categories is a prerequisite for classifying any group of phenomena. Such ability to "typify"106 our experience is therefore one of the cornerstones of social reality

Classification is the mechanism for making sense of disparate objects through the process of lumping and making differences invisible.

-

A mental field is basically a cluster of items that are more similar to one another than to any other item. Generating such fields, therefore, usually involves some lumping.

Evokes Bowker and Star's boundary object work re: the mental models of lumping and splitting

-

Such mental geography has no physical basis but we experience it as if it did

Evokes Moser's cognitive mental models and Borditsky's spatial metaphor work on how we use the language of physical space to carve out understanding about self and the social/cultural concepts.

-

Like them, all frames basically define parts of our perceptual environment as irrelevant, thus separating that which we attend in a focused manner from all the out-of-frame experience44 that we leave "in the background" and ignore.

Evokes Geertz' advice in ethnographic thick description to focus on the details in order to make sense of the situational context and place people/events in an interpretative frame.

-

A frame is characterized not by its contents but rather by the distinctive way in which it transforms the contents' meaning.

How does this square with the definition of "boundary objects"?

-

Framing is the act of surrounding situations, acts, or objects with mental brackets35 that basically transform their meaning by defining them as a game, a joke, a symbol, or a fantasy

Definition of framing.

-

Crossing the fine lines separating such experiential realms from one another involves a considerable mental switch from one "style" or mode of experiencing to another, as each realm has a distinctive "accent of reality. "30

Evokes the notion of pluritemporal time.

Lookup this citation.

-

Temporal differentiation often entails an experience of discontinuity among different sorts of reality as well.

This sense of discontinuity is problematic in determining situational awareness during crisis/emergency information work when it's not always evident what is live, what is recorded, and what is algorithmically delayed.

-

Temporal differentiation helps substantiate elusive mental distinctions. Like their spatial counterparts, temporal boundaries often represent mental partitions and thus serve to divide more than just time.

Temporal boundaries (and the objects inherent in them) are used to convey additional meaning and context. These partitions are used to describe historical distinctions ("The Great Depression", "Vietnam Era"), life distinctions (work vs private time vs religious observance).

Examples above are from the chapter.

-

In order to endow the things we perceive with meaning, we normally ignore their uniqueness and regard them as typical members of a particular class of objects (a relative, a present), acts (an apology, a crime), or events (a game, a conference).2 After all, "If each of the many things in the world were taken as distinct, unique, a thing in itself unrelated to any other thing, perception of the world would disintegrate into complete meaninglessness. "3 Indeed, things become meaningful only when placed in some category.

Connect this to Bowker and Star (2000) Sorting Things Out.

-

The perception of supposedly insular chunks of space is probably the most fundamental manifestation of how we divide reality into islands of meaning. Examining how we partition space, therefore, is an ideal way to start exploring how we partition our social world

Zerubavel describes how we use space to partition meaning from large, complex or unfamiliar objects.

Evokes the notion of a boundary object.

-

- Aug 2018

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

create the effect of temporal symmetry, of the group sharing a moment, even though individual members clearly read the message at different moments.

description of temporal symmetry

-

The notion of temporal structuring views "real time" not as an inherent property of Internetbased activities, or an inevitable consequence of technology use, but as an enacted temporal structure, reflecting the decisions people have made about how they wish to structure their activities, both on or off the Internet. As an alternative to the idea of '·real time," Bennett and Wei II ( 1997) have suggested the notion of "real-enough time," proposing that people design their process and technology infrastructures to accommodate variable timing demands, which are contingent on task and context. We believe such "real-enough" temporal structures are important areas of further empirical investigation, allowing us to move beyond the fixation on a singular, objective "real time" to recognize the opportunities people have to (re)shape the range of temporal structures that shape their lives.

real time vs real-enough time

-

The notion of temporal structuring we have developed here suggests instead that people enact multiple, heterogeneous, and shifting temporal structures in all aspects of their lives.

people experience temporal structures as dynamic

-

Our empirical example also highlighted the value of achieving virtual temporal symmetry for members of a geographically dispersed community. As electronic media become increasingly central to organizational life, individuals may use asynchronous media in various ways to shape devices of virtual symmetry that help them coordinate across geographical distance and across multiple temporal structures. This suggests that when studying the use of electronic media, researchers should pay attention to the conditions in which virtual temporal symmetry may be enacted to coordinate distributed activities, and with what consequences. Interesting questions for empirical research include the following. As work groups in organizations become more geographically dispersed and/or more dependent on electronic media, do members enact virtual temporal symmetry for certain purposes? If so, for which types of purposes? And how? If not, how do such work groups achieve temporal coordination?

virtual coordination across geographic distance via electronic media and how it shapes/is shaped by temporal structures

-

By examining a community's repertoire of temporal structures, we can understand the variety of ways in which community members' actions (re)produce the different temporal structures they constitute through their ongoing practices

A good justification for the SBTF study.

-

The notion of temporal structuring focuses attention on what people actually do temporally in their practices, and how in such ongoing and situated activity they shape and are shaped by particular temporal structures. By examining when people do what they do in their practices, we can identify what temporal structures shape and are shaped (often concurrently) by members of a community; how these interact; whether they are interrelated, overlapping, and nested, or separate and distinct; and the extent to which they are compatible, complementary, or contradictory.

Different interaction patterns of temporal structures that are shaped by people and shape people's activities.

-

In all these cases, the notion of temporal structuring through ongoing practices helps us understand and bridge the temporal oppositions underlying the research literature. We tum now to an empirical example to demonstrate how this perspective can offer a new understanding of the temporal conditions and consequences of organizational life.

Succint summation of previous section and transition.

-

In practice, however. an open-ended or closed temporal orientation is not a stable property of occupational groups, but an emergent property of the temporal structures being enacted at a given moment by the groups' members.

describes how a group orients around an emergent property of temporal structures depending on context.

Orlikowski and Yates write later in this passage:

"Moreover, point of view and moment of observation may also affect the type of structuring observed."

-

Viewed from a practice perspective, the distinction between cyclic and linear time blurs because it depends on the observer's point of view and moment of observation. In particular cases, simply shifting the observer's vantage point (e.g., from the corporate suite to the factory floor) or changing the period of observation (e.g., from a week to a year) may make either the cyclic or the linear aspect of ongoing practices more salient.

Could it be that SBTF volunteers are situating themselves in time as a way to respond to a cyclic/linear tension? or a spatial tension?

-

An emphasis on the cyclic temporality of organizational life also underpins the work on entrainment, developed in the natural sciences and gaining currency in organization studies. Defined as "the adjustment of the pace or cycle of one activity to match or synchronize with that of another" (Ancona and Chong 1996, p. 251 ), entrainment has been used to account for a variety of organizational phenomena displaying coordinated or synchronized temporal cycles (Ancona and Chong 1996, Clark 1990, Gersick 1994, McGrath 1990).

Entrainment definition.

-

In spite of the general movement from particular towards universal notions of time (Castells 1996, Giddens 1990, Zerubavel 1981 ), we can see that in use, all uni versa! temporal structures must be particularized to local contexts because they are enacted through the situated practices of specific community members in specific locations and time zones.

Cites Castells (networks), Giddens (structuration) and Zerubavel (semiotics) as moving away from particular time to more universal notions of real-time, 24-hour clock, and calendars, respectively.

Orlikowski and Yates argue that even universal notions need situated and contextual practices to make sense of time.

-

One such opposition is that between universal (global, standardized, acontextual) and particular (local, situated, contextspecific) time.

Orlikowski and Yates describe situated, contextual time as particular.

-

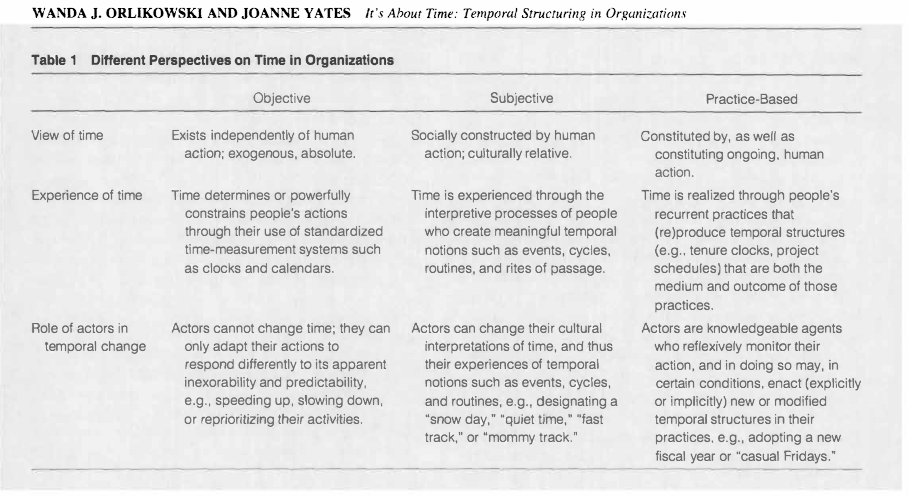

Table 1 Different Perspectives on Time in Organizations

Objective vs Subjective vs Practice-based perspectives in time

-

That is, people are purposive, knowledgeable, adaptive, and inventive actors who, while they are shaped by established temporal structures, can also choose (whether explicitly or implicitly) to (re)shape those temporal structures to accomplish their situated and dynamic ends.

People can enact their agency through practices, habits or planned intentions to change temporal structures against what frequently feels like an external time that operates independently.

-

scholars have begun to recognize the importance of what Nowotny (1992, p. 424) has termed pluritemporalism"the existence of a plurality of different modes of social time(s) which may exist side by side." Our structuring lens sees this not so much as the existence of multiple times, but as the ongoing constitution of multiple temporal structures in people"s everyday practices.

Cites Nowotny's pluritemporalism.

Orlikowski and Yates interpret this as enacting multiple temporal structures that are often interdependent and can also be in conflict. Raises the example of tensions between work and family temporal structures.

-

Like social structures in general (Giddens 1984 ), temporal structures simultaneously constrain and enable.

The paper provides an example of how work vacations and office schedules are restricted during certain seasons, and more open in other seasons.

-

While adopting one side or the other of this dichotomy may offer researchers analytic advantages in their temporal studies of organizations, difficulties arise when these positions are treated-not as conceptual tools-but as inherent properties of time. Focusing on one side or the other misses seeing how temporal structures emerge from and are embedded in the varied and ongoing social practices of people in different communities and historical periods, and at the same time how such temporal structures powerfully shape those practices in turn. By focusing on what organizational members actually do, our practice-based perspective on temporal structuring may offer new insights into how people construct and reconstruct the temporal conditions that shape their lives.

Nice summation of how practice-based experiences of time are not well-served by treating the objective-subjective dichotomy as properties of time.

Need for a different perspective to explore other emergent ways people engage with or experience time.

-

Event time, in contrast, is conceived as "qualitative time-heterogeneous, discontinuous, and unequivalent when different time periods are compared" (Starkey

Event time definition -- as qualitative.

How does this help describe friction of SBTF social coordination attempting to handle mechanical clocktime (timestamps, urgency, timelines, etc.) and dynamic event time (disaster unfolds, rhythms, horizons, etc.)

-

Thus temporal structures, like all social structures (Giddens 1984), are both the medium and the outcome of people's recurrent practices.

Wrapping Giddens' structuration theory into the concept of temporal structures.

-

Our purpose in this paper is to develop the basic outlines of an alternative perspective on time in organizations that is centered on people's recurrent practices that shape (and are shaped by) a set of temporal structures. We see this emphasis on human practices (as distinct from external force or subjective construction) as bridging the current opposition between objective and subjective conceptualizations of time, and thus as making possible a new understanding of the temporal conditions and consequences of organizational life. By grounding our perspective in the dynamic capacities of human agency we believe we gain unique insights into the creation, use, and influence of time in organizations.

Strong why does this matter section -- 3 sentences.

-

This integration suggests that time is instantiated in organizational life through a process of temporal structuring,1 where people (re)produce (and occasionally change) temporal structures to orient their ongoing activities.

Succinct definition of temporal structures.

-

In this paper we explicitly integrate the notion of social practices from this literature with that of enacted structures drawn from the theory of structuration (Giddens 1984 ), arguing that the combination can be valuable for the study of organizations in general and of time in organizations in particular. With respect to the latter, we have obtained important insights into how temporality is both produced in situated practices and reproduced through the influence of institutionalized norms.

Turns of phrase:

"We explicitly integrate the notion of social practices from this literature ..."

"We have obtained important insights ..."

-

We contribute to this discussion within organizational research by offering an alternative third view-that time is experienced in organizational life through a process of temporal structuring that characterizes people's everyday engagement in the world. As part of this engagement, people produce and reproduce what can be seen to be temporal structures to guide, orient, and coordinate their ongoing activities.

How the concept of temporal structures fits in the literature.

-

researchers explore the embodied. embedded. and material aspects of human agency in constituting particular social orders (Hutchins 1995, Lave 1988, Suchman 1987).

Nice succinct high-level summary of DCog, LPP, and situated learning.

-

emporal structures here are understood as both shaping and being shaped by ongoing human action, and thus as neither independent of human action (because shaped in action), nor fully determined by human action (because shaping that action). Such a view allows us to bridge the gap between objective and subjective understandings of time by recognizing the active role of people in shaping the temporal contours of their lives, while also acknowledging the way in which people's actions are shaped by structural conditions outside their immediate control.

Temporal structures definition

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

People are often thrown into pre-existing, organized action patterns. They experience the middle of a narrative but only the vaguest beginnings or ends. Without those boundaries people dwell in antenarrative. But that is where sense-making, organizing, and discursive devices make a difference. ‘People who are thrown establish their own temporality’ (Hernes and Maitlis, 2010: 31)

This is the sociotemporal hook for the SBTF study.

Read the Hernes and Maitlis paper

"People who are thrown establish their own temporality" << what does this mean?

-

‘Antenarrative is the fragmented, non-linear, incoherent, collective, unplotted and pre-narrative speculation, a bet’ (Boje, 2001: 1). Organizing, in the context of antenarrative, is a bet that these fragments will have become orderly and that efforts to impose temporality

This is the sociotemporal hook for the SBTF study.

Antenarrative definition from Boje (2001).

See: Dawson and Sykes (2018) https://via.hypothes.is/http://wendynorris.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Dawson-and-Sykes-2018-Concepts-of-Time-and-Temporality-in-the-Storytelling-and-Sensemaking-Literatures-A-Review-and-Critique.pdf

This runs counter to the more frequent linear time structure of narratives.

The wikipedia article makes a bit more sense:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antenarrative

"Antenarratives serve a similar purpose. The process of moving from the nebulous and chaotic story to a narrative with a beginning middle and end is the antenarrative faith that story fragments will make retrospective sense some time in the future."

More info on antenarrative here:

"The antenarrative is pre-narrative, a bet that a fragmented polyphonic story will make retrospective, narrative, sense in the future. In a recent description of the bet aspect of antenarrative Karl Weick has said "To talk about antenarrative as a bet is also to invoke an important structure in sense-making; namely, the presumption of logic (Meyer, 1956)."

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

‘Antenarrative is the fragmented,non-linear, incoherent, collective, unplotted, and pre-narrative speculation, a bet. To traditional narrativemethods antenarrative is an improper storytelling awager that a proper narrative can be constituted’(Boje 2001, p. 1).

Antenarrative definition.

This runs counter to the more frequent linear time structure of narratives.

The wikipedia article makes a bit more sense:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antenarrative

"Antenarratives serve a similar purpose. The process of moving from the nebulous and chaotic story to a narrative with a beginning middle and end is the antenarrative faith that story fragments will make retrospective sense some time in the future."

More info on antenarrative here:

"The antenarrative is pre-narrative, a bet that a fragmented polyphonic story will make retrospective, narrative, sense in the future. In a recent description of the bet aspect of antenarrative Karl Weick has said "To talk about antenarrative as a bet is also to invoke an important structure in sense-making; namely, the presumption of logic (Meyer, 1956)."

-

Sixth, investi-gating the use of temporal modalities in making andgiving sense in the storytelling of management andother occupational groups, for example, in processesof story-weaving in the assembly of smaller storiesthat variously draw from the past, present and future(see Maitlis 2005, p. 45; Reissner and Pagan 2013,pp. 52, 83)

Future research direction: ??

Look at the citations

-

Fifth, the importance of shifting contextualconditions over chronological time in the rewritingof histories and the reconstruction of narratives thatreposition individuals and groups, in, for example,a movement from hero to villain (see Cunliffe andCoupland 2012; Godfreyet al. 2016).

Future research direction: ??

Read the Cunliffe and Coupland paper

-

Fourth, the com-pression and expansion of time structures in storiesthat compete, and the different techniques for draw-ing on temporal modalities for sensemaking in theconstruction of compelling power-political narrativesthat seek to influence the sense giving of others (seeBuchanan and Dawson 2007; Dawson and Buchanan2012)

Future research direction: Timescapes // Time compression // Post-Colonial and Feminist Time

See: Adam 1990 and 2004 See: Giddens' structuration theory

-

Third, the use of time and temporality for mak-ing and giving sense to unfinalized stories, antenar-ratives and future scenarios (see Boje 2011), includ-ing attention to issues, such as temporal depth, timeurgency and temporal orientation in promoting theneed for short or long-term strategies (see Jabri 2016,p. 97; Kunischet al. 2017, p. 1043)

Future research direction: Temporal depth // Tempo

See: Bluedorn 2002

-

Second, howtime is variously used in past constructions that givesense to what has occurred, in for example, nostal-gic tales that seek to sustain identity-relevant valuesand beliefs, or using time to leverage reformulationsin repositioning these tales, for example, with theaim of undermining nostalgia as a platform for resis-tance (see Brown and Humphreys 2002; Strangleman1999).

Future research direction: Importance of reflexivity // Effects of Time Perspectives on sensemaking

See: Zimbardo & Boyd's Time Perspectives

-

First, exam-ination of time representations in the more finalizedand structured stories in organizations (see Gabriel2000): for example, how time and temporality areused to convey a particular message, moral lesson orpresent a causal explanation that is both compellingand plausible.

Future research direction: Language of time

See: Zerubavel and semiotics

-

Our discussion commences with a fourfold charac-terization of underlying temporal modalities fromwhich we extend six pathways in mapping out fu-ture research opportunities.

1) "finalized retrospective stories’ that seek to reconstruct from the past, key events, characters and plots that provide causal explanations for making sense of current disruptions and ambiguities (these stories take on the Aristotelean convention of being characterized by a beginning, middle and end)"

2) "‘unfinalized prospective stories’ that are forward looking: time is no longer set, but non-linear and indeterminate. These stories of the future are unfinalized (like Boje’s concept of antenarrative), subjective and open to re-storying in seeking to make sense of ongoing and newly emerging occurrences as well as the uncertainties, threats and opportunities of a future that has yet to be."

3) "‘present continuity-based stories’ that attempt to provide some reassurances about sustaining relations and values: to reassert a collective sense of belonging, sense of stability and membership, as in the heightened sense of belongingness through nostalgia (Strangleman 1999) that enables a sense of continuity between what is happening, what happened in the past and what may happen in the future."

4) "‘present change-based stories’ often comprising a mixture of optimism in promoting the benefits of changing for the future, and pessimism in constructing stories on the potential threats and negative implications of future change (aligning with Ybema’s (2004) notion of postalgia)."

-

Boudes and Laroche (2009) attend to narra-tive sensemaking in post-crisis inquiry reports inanalysing the foreseeability of the deaths that oc-curred following the heat wave in France in 2003.They identify a tendency towards simplification andreductionism, but suggest that, rather than represent-ing a linear temporal sequence in which recommen-dations follow explanation, ‘the story is built at leastpartially around preferred lessons and the desiredrecommendations for action’ (Boudes and Laroche2009, p. 392).

Read this paper.

The paper focuses on post-crisis sensemaking. Do they discuss sensemaking in the moment?

-

This returns us to Weick’s (2012) claimthat the unfinalized uncertainties of life experiences ismade sense of and temporally fixed in narrative ratio-nality, but with the added notion that these temporalconstructions build on prospective ideas (a non-lineartemporality in story construction, but not in the struc-ture of the final narrative).

This seems to fit with the Cunliffe and Coupland paper that in the moment actions are non-linear but the narrative is plotted across time (linear).

-

As the authors note: ‘Sensemaking is tempo-ral in at least two ways: in the moment of performancewe draw on past experiences, present interactions andfuture anticipations, and second, we plot narrative co-herence across time’ (Cunliffe and Coupland 2012,p. 83).

This is a helpful frame for thinking about how SBTF volunteers are simultaneously trying to evaluate granular bits of information and add it to a larger emerging story about the event.

This paper also cites Goffman's Presentation of Self

-

However, in their study focusing on theimportance of time to sensemaking in crisis situa-tions, Combe and Carrington (2015) point out thatmost studies still remain focused on objective clocktime with little attempt to examine the influence ofthe subjective experience of the past or how leadersimagine the future may affect how they interpret andmake sense of the present

studies of time and sensemaking in a crisis.

-

Al-though both scholars usefully illustrate the powerof narratives to make and give sense to experiencesin organizations, Gabriel (2000) adopts a folkloristposition with a reliance on conventional temporal-ity and sequenced event time, in which causality isbuilt into the narrative construction with a progres-sive temporality (beginning, middle and end). In con-trast, Boje (2011) is interested in the more fragmentedand terse stories and the ways in which these un-resolved narratives open up possibilities for poten-tial futures (prospective sensemaking).

Contrast of Gabriel and Boje's approaches in a nutshell.

-

As Bojeet al. (2016a, p. 395)indicate, through situating antenarratives in subjec-tive time, they are able to show ‘how diverse voicesinterconnect, embed and entangle in organizationalstrategies’.

Need to unpack this a bit. Is this how to scaffold the SBTF situated time instances into a sensemaking process?

Subjective time (per the philosopher's term) is referred to as socially-constructed time (by the sociologists).

In Brunelle (2017):

*"temporal construals

The way organizational members interpret or situate themselves in time and embrace time-related concepts such as of time scarcity, urgency, orientation. ‘temporal construals inform and are informed by intersubjective, subjective and objective times.’ (R. A. Roe et al., 2009)"*

-

Boje seeks to elevate the place ofstories in organization studies in examining the inter-play between the control of narrative (order) and theunfinalized nature of emergent story (disorder)

How does this manifest (if at all) in crisis social media?

What is represented by the order? What is represented by the disorder?

If crisis social media is performative storytelling, then what does Goffman say about sensemaking?

-

For Boje (2008,p. 1) narrative has served to present reality in an or-dered fashion (the arrow of time), whereas storiesare at times able to break out of this narrative orderand offer a more diverse, fragmented and muddledview of reality (non-linear temporality). He refers toa storytelling organization as a ‘collective storytellingsystem in which the performance of stories is a keypart of members’ sensemaking and a means to allowthem to supplement individual memories with insti-tutional memory’ (Boje 1991, p. 106).

Narrative is linear (arrow of time) Story "in the here and now" is non-linear

-

From Boje’s perspective, coherent narrativesbuilt on retrospective sensemaking serve to controland regulate, while living stories in the present (asin simultaneous storytelling) disperse and challenge,providing alternative interpretations, with antenarra-tives offering future possibilities through prospectivesensemaking

Boje's approach.

-

From thisfolklorist perspective, sequenced event time predom-inates, and conventional temporality is not called intoquestion, and yet there remain subtle and differentconceptions of time, sometimes continuous, some-times discontinuous, sometimes linear and sometimestimeless, that extend beyond a simple characterizationof Newtonian linear-time.

Different types of time are incorporated into stories but the through-line remains linear.

-

Coherent, finalized stories are embedded with alinear structure that aligns with clock time and theGregorian calendar (Gabriel 2000, p. 239). Chronol-ogy and objective time implant these stories withan identifiable past, present and future and a linearcausality that provides a temporal structure (a be-ginning, middle and end with plot and characters).This linearity is tied to the inviolability of sequencedevents that occur within a tensed notion of time where,for example, you cannot have a character seeking re-venge before an original insult has occurred, nor canyou have a punishment for a crime that will be com-mitted later.

For Gabriel, stories have a linear temporal structure (beginning, middle, end) driven by past, present and future events.

-

For Gabriel, stories are a subset of narratives (whileall stories are narratives, not all narratives are stories),arguing that theories, statistics, reports or documentsthat describe events and seek to present objective factsshould not be treated as stories (nor for that mattershould clich ́es), as stories interpret events often dis-torting, omitting and embellishing to engage audienceemotions, they generate, sustain, destroy and under-mine meaning, and while they are crafted along par-ticular lines they do not obliterate the facts (Gabriel2000, pp. 3–4).

Story definition per Gabriel.

SBTF data collection/sensemaking would not be a story, per Gabriel's definition.

But is it sensemaking?

-

A key comparative difference centreson their definition and approach to stories. Gabrielis concerned with completed coherent stories with abeginning, middle and end, whereas Boje examinesunfinalized stories and future-oriented sensemaking.Temporality is central to both and yet, as we willillustrate, concepts of time remain implicit and inad-equately theorized.

Differences between Gabriel's approach and Boje.

-

Thissupported the common claim that, in organizationalresearch, time usually remains hidden or implicit andis seldom discussed explicitly (Roeet al. 2009).

Similar to Nowotny's argument that theory doesn't break through in empirical work.

-

From these readings, a com-mon and persistent claim centred on the general ab-sence of conceptual thinking about time and tempo-rality (Berends and Antonacopoulou 2014; Dawsonand Sykes 2016)

Argues that there is a research gap about conceptual thinking about time and storytelling in the organizational studies literature.

More broadly in other disciplines, Nowotny counters that there is plenty of time/temporal theory but a lack of empirical work that engages it.

-

This dominant linear view of temporality drawnfrom conventional representations of clock time (dig-itally embedded in a range of everyday devices) hasbeen widely criticized (Adam 1990, 2004; Glennieand Thrift 1996; Thrift 2004; Wajcman 2015), witha growing recognition of the need to bring differen-tiated concepts of time to the fore (see Christens-sonet al. 2014). There is a small but expandingcall to move beyond objective time (Allmanet al.2014) and time-free research (Hassard 1990b, p. 1)or timeless knowledge (Roeet al. 2009) to a moreconceptually informed theorization in which conceptsof time are made more explicit and openly discussed(Anconaet al. 2001b; Bluedorn 2002; Dawson andSykes 2016; Goodmanet al. 2001).

Cites the need for more concrete examples and more direct engagement with time in theory.

See: Bluedorn 2002 See: Nowotny

-

This review highlights how conventional explanations in these related fields of studyare underpinned by linear conceptions of temporality (with an associated causality)and how there is growing recognition of fluidity in the way pasts and futures cometogether in temporal sensemaking of an emergent present.

how is "emergent present" defined? Is there a predictive element based on past experience and future expectations?

Is "emergent present" a near-future but not quite real-time dimension of time?

-

ClassicAristotelian narratives with a linear time structure (stories with a beginning, middle andend) are prominent in the storytelling literature, whereas retrospection, in drawing onthe past in making sense of the present, is a temporal modality central to foundationalconcepts of sensemaking. In examining time and temporality in these related fields,the authors show how the conventional temporal sequence of a past, present and futuredominates, with little consideration being given to time as a multiple rather than singularconcept

Is the process of retrospection present as a multitemporal or pluritemporal dimension in SBTF crowdwork that is attempting to build knowledge (situational awareness)?

-

-

cdn.inst-fs-iad-prod.inscloudgate.net cdn.inst-fs-iad-prod.inscloudgate.net

-

These possibili- ties are more likely to be seen if we think of large crises as the outcome of smaller scale enactments. When the enactment perspective is applied to crisis situations, several aspects stand out that are normally overlooked. To look for enactment themes in crises, for example, is to listen for verbs of enactment, words like manual control, intervene, cope, probe, alter, design, solve, decouple, try, peek and poke (Perrow, 1984, p. 333), talk, disregard, and improvise. These verbs may signify actions that have the potential to construct or limit later stages in an unfolding crisis

Curious why temporality is never mentioned as a dynamic of enactment. It's somewhat implied in the idea of acting in the moment or responding after the fact, but sensemaking and social construction is inherently temporal.

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

Theway organizational membersinterpret or situate themselves in time and embrace time-related concepts such as of time scarcity, urgency, orientation. ‘temporal construals inform and are informed by intersubjective, subjective and objective times.’ (R. A. Roe et al., 2009

Get Roe's paper. This helps to bridge the ideas of "situated time" and "subjective time" -- or socially constructed ways of experiencing, thinking about and perceiving time.

See: Dawson and Sykes 2018 See: Pöppel 1978 - https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-46354-9_23

-

mporal features. We have then to consider how organizational participants are affected by situations containing temporal features, but also how these actors shape, by their behavior and beliefs, local context according to their needs.

This provides a good framework for the SBTF study that social coordination practices can sometimes be at odds with the "structures that bear significant temporal features."

Could this mean data as well as events?

Is this passage invoking activity theory, if it were an HCI study?

-

To this extent, we have made tremendous advancements but we are still lacking reliable findings of the consistency and magnitude of the time effects at each level of an organization and on individuals. Perhaps, the last progresses that drawn upon the sructuration theory (Gomez, 2009; Kaplan & Orlikowski, 2013; Wanda J. Orlikowski & Yates, 2002; Reinecke & Ansari, 2015; Rowell, Gustafsson, & Clemente, 2016) has suffered the same faith of being judged as too notional and not providing enough guidance on how to conduct empirical studies based on this conception.

Brunelle identified same gap as Nowotny, some 30 years later that theory is not serving empirical research.

-

empirical literature on organizational time has extended research on time as a control variable of boundary condition (George & Jones, 2000; Langley, Smallman, Tsoukas, & Van de Ven, 2013)

How is boundary condition being used here? As a boundary object or something else?

See: Busse 2017 (in Mendeley)

-

Events have a time span; actions have a time frame that highlights the urgency of (continuously) deepening our knowledge of time as a key component of organizations (Bleijenbergh, Gremmen, & Peters, 2016). In

Interesting way to temporally frame events as a span vs activity as a time frame/tempo.

-

But time is a complex and a sensitive topic in reason to the different vantage points; and its meaning often tends to be taken for granted and given commonsense or self-evident attributions (Sahay, 1997).

Read this paper.

Sahay, S. (1997). Implementation of information technology: a time-space perspective. Organization Studies, 18, 229–260

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

A promising approach that addresses some worker output issues examines the way that workers do their work rather than the output itself, using machine learning and/or visualization to predict the quality of a worker’s output from their behavior [119,120]

This process improvement idea has some interesting design implications for improving temporal qualities of SBTF data: • How is the volunteer thinking about time? • Where does temporality enter into the data collection workflow? • What metadata do they rely on? • What is their temporal sensemaking approach?

-

Many tasks worth completing require cooperation –yet crowdsourcing has largely focused on independent work. Distributed teams have always facedchallenges in cultural differences and coordination[60], but crowd collaboration now must createrapport over much shorter timescales(e.g., one hour) and possibly wider culturalor socioeconomic gaps

In Kittur's example, synchronous collaboration describes a temporal aspect (timescale and tempo of the work) related to how the collaboration is structured or not.

"Short periods of intense crowd collaboration call for fast teambuilding and may require the automatic assignment of group members to maximize collective intelligence."

-

The two core challenges for realtime crowdsourcing will be 1) scaling upto increased demand for realtime workers, and 2) making workers efficient enough to collectively generateresultsahead of time deadlines.

One aspect of temporality in Kittur's study is related to "realtime" which they describe as the time need to scale up workers and efficiency speed of workers.

The other temporal aspect is synchronicity of workers.

-

-

emlis.pair.com emlis.pair.com

-

There is also a need for mechanisms to support transformations and processesover time, both for scientific data and scientific ideas. These mechanisms should not only help the user visualize but also express time and change.

This is still true today. Is the problem truly a technical one or an opportunity to re-imagine the human process of representing time as an attribute and time as a function of evolving data?

-

Compared to paper artifacts such as laboratory notebooks, computer files do not offer a proper structure to manage temporal and evolutive data.

Don't agree with this statement at all. Blogs are nothing but linear chronological structures.

-

Paper holds temporal properties which are not yet integrated in computer.

Also, weirdly overstated. There were plenty of products and meta data even in 2009 that was available to determine provenance and iteration.

-

Contrary to paper notes, computer files do not display the traces or versions that led to their final state.

This seems weirdly overstated. How do paper notes maintain versions and traces? Electronic documents contain rich sources of meta data for trace analysis, as well as various options to explicitly demonstrate temporal order and change through formatting.

-

Blog tools are designed as publishing tools; they do not support iterative thinking the way paper notebooks do.

This statement seems to be fixed in traditional, old-school blogging (one idea = one post) and doesn't consider other forms that adapt/extend other ways to represent temporality/change/iteration.

As one example, live-blogging techniques which incorporate rapid updating of new information through chronological mini-posts, manual time-stamping of new material, etc. Also. plug-ins that allow annotation, image uploads, Google Docs with version control, etc.

Also, WP post/page formatting options with HTML, typography, etc., can augment re-ordering of information to designate change.

-

As researchers explore different projects, it is difficult to put order in their ideas, their framing changes andtransitions or regrouping occur [figure 1] (time as change). When the projects are over, defined, researchers can refer to them as a whole and situate them in time (time as order).

I don't understand this section.

-

At a higher level, with their roadmaps and deadlines, projects also hold a temporal dimension.

The DHN analog to projects could be the deployment and/or the humanitarian event temporality (slow-onset, rapid-onset and chronic).

-

This is related to the fact that biology researchers are in a creative process and reflect on their decisions in order to explore new leads or justify their decisions. Paper laboratory notebooks show this temporality ofthoughts.

The iterative self-reflection process described in biology research seems relatively undeveloped in DHN work. I don't know that I've seen much negotiation/reflection/critical analysis take place between the moment the data is collected by volunteers and the maps/viz/data/after-action reports created after the fact by the Core Team.

Perhaps that's a missing element that should be more deeply explored in thinking about data having both a time attribute and being in a state of change? Is there a needed intermediate validation step between data cleaning and creating a data analysis product.

-

We illustrate how the time as change paradigm helps to better capture the dynamic aspects of their data through three types of data temporality: TODO lists, reflective activity (biology research) and project management.

One idea as an analog to the biologist example for DHN work is: data sheet (3W or other configuration depending on the deployment type), volunteers' sensemaking activity, and coordination work.

-

Temporal data can thus be described either as data having time attributes, or data needing a dynamic description, acknowledging data temporal dimension - what we call temporality.

Re-defining temporality seems less helpful here. It's already a confusing and contested concept. No need to further complicate it.

-

This corresponds to a classical and quite well-established distinction in the history of ideas: time as order, and time as change [Wolff 2004].

Get this paper.

-

Time as order considers temporal data as data that can be described by a time attribute, which can improve navigation or organization. Time as change considers temporal data as data that evolve over time.

The contrast of time as representing either order or change could be a very helpful way to categorize messy, dynamic humanitarian crisis data.

We need ways to capture data as an event timeline (X happened, then Y which demands response Z) as well acknowledge that X and Y may be in flux in an evolving crisis zone.

-

Temporal Data and Data Temporality: Time is change, not only ord

Synthesis:

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

While Activity Theory provides a useful lens for understanding users’ work practices and a language for communicating models of users’ behavior, there are some aspects of work practice that have been shown to be critical for knowledge work but are not captured in the Activity Theory framework. For example, knowledge workers have been shown to rely on the organization of information used in ongoing activities to accomplish their work, particularly when the value or role of that information has not yet been fully determined (Kidd, 1994; Malone, 1983; Mynatt, 1999). Activity Theory alludes to the fact that tools reflect the history of their use, but does not place a strong emphasis on this critical component of knowledge work.

limit of activity theory

-

s a means for coordinating action among groups of users (e.g., Bardram, 2005, this volume)

social coordination and activity theory

get this paper

Bardram, J.E. (2005, September). Activity-based computing: Support for mobility and collaboration in ubiquitous computing. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 9(5), 312–322.

-

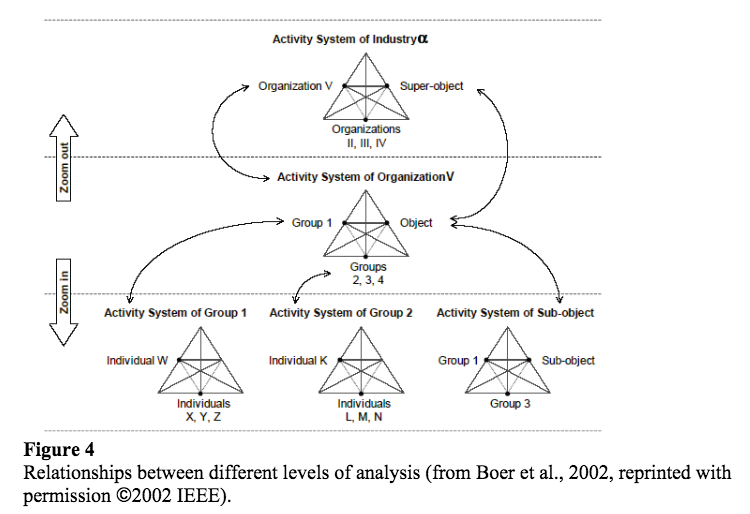

The hierarchical structure of the Boer et al. adaptation of the Activity Theory model can help to reconcile the differences in granularity and the difficulties of supporting collaboration identified in our work; future activity-centered user interfaces might take advantage of the zoomable user interface paradigm or feature control over the level of detail (LOD) represented in the interface to more accurately reflect the depth at which a given user conceptualizes their own tasks or the tasks of their colleagues.

Boer extension attends to some of the challenges which began this paper

-

Activity Theory casts a wide but well-defined net around the multifaceted nature of activity, suggesting that the user’s colleagues and the object of the activity are of the utmost importance, but that the tools, social rules, and roles of collaborators within the community must also be reflected back to the user as critical components of that activity. The idea that components of activity reflect their history of use through time suggest several ways for activity-centered systems to support a dynamic working landscape; for example, they might capture past activities in an archive for quick—and potentially automated—reference during related tasks in the future, and that the tools used in previous and ongoing activities (e.g., documents and information resources) both be available at all times and tagged with meta-information about how they have been used in the past

Further description of how activity theory could incorporate temporality through history (past), dynamic (tempo), automated references (future), and toolsets (past, previous).

-

Engeström (1987) provides a classic visualization summarizing the structure of an activity (figure 3). This model is based around three mutual relationships: that between the actor (subject) and the community (other actors involved), that between subject and the object (in the sense of objective) of the activity, and that between the object and the community. These mutual relationships are mediated by the other components of activity.

Engeström definition of Activity Theory

-

Activity Theory is described both as a guiding framework for analyzing observations of work practice and a language for communicating those findings within the community of practitioners (Halverson, 2001).

description of Activity Theory

-

Nardi (1996) argues that one of the inherent strengths of Activity Theory is in its ability to capture the idea of context in user models for HCI, a notion that is gaining momentum particularly with respect to the ubiquitous computing paradigm and as its own design movement, so-called activity-centered design (Gay & Hembrooke, 2003). The world that Gay and Hembrooke envision relies upon design that is not user-centered (which is currently the dominant view in the HCI community) but activity-centered, since Activity Theory provides the right “orientation” for future classes of interactions mediated by ubiquitous computing devices.

activity-based design -- a companion to user-centered design

-

Besides the fact that an activity is situated in a network of influencing activity systems, it is also situated in time....In order to understand the activity system under investigation, one therefore has to reveal its temporal interconnectedness....Rather than analyzing an activity system as a static picture of reality, the developments and tensions within the activity system need to be

extension of Activity Theory with a temporal dimension

Boer et al quote continues on next page but not picked up in annotation.

Cites Giddens' structuration theory

-

However, Gay and Hembrooke point out a weakness in the original formulation of Activity Theory: “The model of activity theory...has traditionally been understood as a synchronic, point-in-time depiction of an activity. It does not depict the transformational and developmental processes that provide the focus of much recent activity theory research” (Gay & Hembrooke, 2003).

criticism of Activity Theory -- as point-in-time and missing transformational/developmental processes.

Not discussed here but those deveopmental processes have temporal qualities and attributes

-

In their well-known “activity checklist,” Kaptelinin, Nardi, and Macaulay (1999) identified five basic principles of Activity Theory: 1.Hierarchical structure of activity In Activity Theory, the unit of analysis is an activity which is directed at an objectthat motivates the activity. Activities are composed of conscious, goal-directed actions; different actions may be taken to complete any given goal. Actions are implemented through automatic operations, which do not have goals of their own. This hierarchical structure is dynamic and can change throughout the life of an activity. 2.Object-orientedness Activity Theory holds that humans exist in an broadly-defined objective reality, that is, the things around us have properties that are objective both to the natural sciences and society and culture. 3.Internalization/externalization Activity Theory considers both internal and external actions and holds that the two are tightly interrelated. Internalization is the process of transforming an external process into an internal one for the purposes of planning or simulating an action without affecting the world. Externalization transforms internal actions into external ones and is often used to resolve failures of internal actions and to coordinate actions among independent agents. 4.Mediation A central tenet of Activity Theory is that activity is mediated by tools, and that these tools are created and transformed over the course of the activity so that the culture and history of the activity becomes embedded in the tools. Vygotsky’s definition of tool is very broad; one of the tools he was most interested in was language. 5.Development Activity Theory relies upon development as one of its primary research methodologies; that is, “experiments” often include consist of a subject’s participation in an activity and observation of developmental changes in the subject over the course of the activity. Ethnographic methods that identify the cultural and historical roots of activity are also frequently used.

Nardi definition of Activity Theory

Also: INFO 6101 paper

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1uefIe_9c-ZLuTsMPGGV5iyKQsteeEA8vR405S7vYK_0/edit

-

Activity Theory places a strong focus on the mediating role of tools and social practices in the service of accomplishing goals

activity theory focus

-

In particular, the fact that most users are only now beginning to experience the ubicomp vision and integrate this new, unique class of technology into their work practices suggests that another change in focus may be on the horizon: “[T]he shift from user-centered design to context-based design corresponds with recent developments in pervasive, ubiquitous computing networks and in the appliances that connect with them, which are radically changing our relationships with personal computing devices” (Gay & Hembrooke, 2003)

Influence of ubiquitous computing on HCI

-

Over the last decade, the focus of the HCI community began to shift away from the quantitative evaluation of user interfaces based on cognitive models and towards more ecologically informed techniques, including contextual and participatory design (Beyer & Holtzblatt, 1998; Kyng, 1994). This “user-centered design” movement foregrounded the social context of technology use and incorporated user feedback and participation throughout the design process.

contemporary HCI focus

-

Historically, HCI adopted and adapted knowledge, processes and techniques from artificial intelligence (AI), cognitive science, and cognitive psychology in service of understanding and modeling user behavior, and applied those findings to the creation of new interfaces and technologies through design practice. As a result of this lineage, many of the theories and techniques used in HCI to model users have exhibited a markedly cognitive, “agents as information processors” flavor. As a result, much of the research literature on user modeling in HCI has been based on the Model Human Processor (Card, Moran & Newell, 1983), which has its roots in the physical symbol system hypothesis.

historic grounding of HCI basic and applied research.

-

Activities also span place; that is, it is common for work to take place outside of the immediate office environment. However, current office technologies sometimes present a very different view of information across different physical and virtual settings.

"Activities exist across places"

Here the paper conceptualizes "place" as physical location as well as mobile environment.

-

The idea that activities may exist at different levels of granularity is not a new one. Boer, van Baalen & Kumar (2002) provide a model explaining how an activity at one level of analysis may be modeled as an action—a component of an activity—at another. This holds true for individual users, as in the example provided above, but is even more pronounced when a single activity is viewed from multiple participants’ perspectives.

"Activities exist at different levels of granularity"

Hierarchical level of analysis; Action < Activity

The idea of granularity also seems to have a temporal component. See examples before this passage.

-

Additionally, activities need to be represented in such a way that their contents can be shared, with the caveats that individual participants in an activity may have very different perceptions of the activity, they may bring different resources to play over the course of the activity, and, particularly for large activities in which many individual users participate, users themselves may come and go over the life of the activity.

Large group social coordination challenges are particularly salient to the SBTF studies.

-

Recognizing the mediating role of the digital work environment in enabling users to meaningfully collaborate is a critical step to ensuring the success of these systems.

"Activities are collaborative"

Activity representations are also crucial here, as is the "mediating role of the digital work environment" for collaboration.

Flag this to connect to the Goffman reading (Presentation of Self in Everyday Life) and crowdsourcing/collective intelligence readings.

-

User studies and intuition both suggest that the activities that a knowledge worker engages in change—sometimes dramatically—over time. Projects and milestones come and go, and the tools and information resources used within an activity often change over time as well. Furthermore, activities completed in the past and their outcomes often impact activities in the present, and ongoing activities will, in turn, affect activities that will be undertaken in the future. Capturing activity over the course of time has long been a problem for desktop computing.

"Activities are dynamic"

This challenge features temporal relationships between work and worker, in the past/present sense, and work and goals, in the present/future sense.

Evokes Reddy's T/R/H temporal organization of work and Bluedorn's work on polychronicity.

-

Supporting the multifaceted aspects of activity in a ubicomp environment becomes a much more complex proposition. If activity is to be used as a unifying organizational structure across a wide variety of devices such as traditional desktop and laptop computers, PDAs, mobile telephones, personal-server style devices (Want et al., 2002), shared public displays, etc., then those devices must all be able to share a common set of activity representations and use those representations as the organizational cornerstone for the user experience they provide. Additionally, the activity representations must be versatile enough to encompass the kinds of work for which each of these kinds of devices are used

"Activities are multifaceted"

This challenge is premised on having a single unit of analysis -- activity -- and that representations of the activity are both valid (to the user) and versatile (to the work/task type)

-

The challenges exist due in large part to the inherent complexity of human activity, the technical affordances of the computing tools used in work practice, and the nature of (and culture surrounding) knowledge work.

Reasons behind the knowledge work challenges.

-

knowledge workers—business professionals who interpret and transform information (Drucker, 1973).

knowledge worker definition

-

We describe five challenges for matching computation to activity. These are: •Activities are multifaceted, involving a heterogeneous collection of work artifacts; •Activities are dynamic, emphasizing the continuation and evolution of work artifacts in contrast to closure and archiving; •Activities are collaborative, in the creation, communication, and dissemination of work artifacts; •Activities exist at different levels of granularity, due to varying durations, complexity and ownership; and •Activities exist across places, including physical boundaries, virtual boundaries of information security and access, and fixed and mobile settings.

These challenges also have temporal qualities, e.g., tempo/speed, duration, timeline, etc.

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

In order to endow the things we perceive with meaning, we normally ignore their uniqueness and regard them as typical mem-bers of a particular class of objects (a relative, a present), acts (an apology, a crime), or events (a game, a conference).

Connect this to HCC reading: Bowker and Star (2000) Sorting Things Out.

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

Nature has been incorporated into social theorizing only in as far as it either has become an object to which meaning is attributed and which hence figures as part of human reflexivity, as object met with emotions or attitudes; or, it is seen as an object of transformation by those forces which act upon it: economic forces, but foremost forces emanating from science and technology. The natural environment, including the biosphere and a multitude of environmental risks which have come to the fore today, negate clear-cut boundaries between the effects of human intervention, and hence agency, and synergistic processes which are 'natural' but still a result of human interaction with the environment. Time, it has been emphasized, is not only embedded in symbolic meaning or intersubjective social relations but also in artifacts, in natural and in culturally made ones. Likewise, the ongoing transformation and endangering of the natural environment is performed by processes which are chemical and atmospheric, biological and physical. But they all interact with social processes tied to energy production and use, modes of food production and land utilization, demographic pressures and possible interferences through use of tech-nology.

Nowotny seems to share Adam's concern about extracting nature and natural time from social constructions of time.

Perhaps this is a good place to embed the study's disaster event temporality as a way to further make sense of DHN social coordination and actions/reactions of disaster-affected people?

-

This means also that the predominantly linear time is comp-lemented by greater awareness of cyclical times and temporal routines which are overlapping each other.

Evokes Adam's timescape concepts of other shapes/dimensions beyond linear/clock time experiences.

This passage also seems to touch on Reddy et al's focus on temporal rhythms as an activity strategy

-

Social identities have increasing difficulty in being construed in terms of stable social attributes in a highly mobile -both socially and geographically - society. They will have to rely on other, temporal dimensions, in what are becoming increasingly precari-ous, if not completely contingent, identities in constant need of redefi-nition. One's 'own', proper time situated in a momentous present which is extended on the societal level in order to accommodate the pressing overload of problems, choices and strategies, becomes a central value for the individual as well as a characteristic of the societal system (Nowotny, 1989a)

I'm curious how this idea of mobility creates a precarious, contingent identity which forces people to use other temporal dimensions to situate themselves.

This could be an interesting way to approach the situated time phenomena I'm seeing in the SBTF study.

-

Major societal transformations are linked to information and communication technologies, giving rise to processes of growing global interdependence. They in turn generate the approxi-mation of coevalness, the illusion of simultaneity by being able to link instantly people and places around the globe. Many other processes are also accelerated. Speed and mobility are thus gaining in momentum, leading in turn to further speeding up processes that interlink the move-ment of people, information, ideas and goods.

Evokes Virilio theories and social/political critiques on speed/compression, as cited by Adam (2004).

Also Hassan's work, also cited by Adam (2004).

-

ut it will also have to come to terms with confronting 'the Other' (Fabian, 1983), with 'the curious asymmetry' still prevailing as a result of advanced industrial societies receiving a mainly endogenous and synchronic analytic treatment, while 'developing' societies are often seen in exogenous, diachronic terms. Study of 'Time and the Other' presupposes, often implicitly, that the Other lives in another time, or at least on a different time-scale. And indeed, when looking at the integrative but also potentially divisive 'timing' facilitated by modern communication and information-processing technology, is it not correct to say that new divisions, on a temporal scale, are being created between those who have access to such devices and those who do not? Is not one part of humanity, despite globalization, in danger of being left behind, in a somewhat anachronistic age?

Nowotny argues that "the Other" (non-western, developing countries, Global South -- my words, not hers) is presumed to be on a different time scale than industrial societies. Different "cultural variations and how societal experience shapes the construction of time and temporal reference..."

This has implications for ICT devices.

-

only structural functional theory, but all postfunctionalist 'successor' theories for their lack in taking up 'substantive' temporal issues, he was also pleading from the selective point of view of Third World countries for the exploration of theoretically possible alternatives or, to put it into other words, the delineation of what in the experience of western and non-western societies so far is universally valid and yet historically restric-ted. Such questions touch the very essence of the process of moderniz-ation. They evoke images of a closed past and an open or no longer so open future, of structures of collective memory as well as shifting collec-tive and individual identities of people who are increasingly drawn into the processes of world-wide integration and globalization. Anthropologi-cal accounts are extremely rich in different time reckoning modes and systems, in the pluritemporalism that prevailed in pre-industrialized societies. The theory of historical time - or times - both from a western and non-western point of view still has to be written. There exists already an impressive corpus of writings analysing the rise of the new dominant 'western' concept of time and especially its links with the process of industrialization. The temporal representations underlying the different disciplines in the social sciences allow not only for a reconceptualization of their division of intellectual labour, but also for a programmatic view forward towards a 'science of multiple times' (Grossin, 1989). However, any such endeavour has to come to terms also with non-western temporal experience.

Evokes Adam's critique of colonialization of time, commodification/post-industrial views, and need for post-colonial temporal studies.

-

Time' and time research is not ·an institutionalized subfield or subspeciality of any of the social sciences. By its very nature, it is recalcitrantly transdisciplinary and refuses to be placed under the intellectual monopoly of any discipline. Nor is time sufficiently recognized as forming an integral dimension of any of the more permanent structural domains of social life which have led to their institutionalization as research fields. Although research grants can be obtained for 'temporal topics', they are much more likely to be judged as relevant when they are presented as part of an established research field, such as studies of working time being considered a legit-imate part of studies of working life or industrial relations.

Challenges of studying time and avoiding the false claim that is a neglected subject.

-

The standardization of local times into standard world time is one of the prime examples for the push towards standardization and integration also on the temporal scale (Zerubavel, 1982).

Get this paper.

Zerubavel, E. (1982) 'The Standardization of Time: A Sociohistorical Perspective', American Journal of Sociology 1: 1-12.

-

At present, information and communication technologies con-tinue to reshape temporal experience and collective time consciousness (Nowotny, 1989b)

Get this paper.

Nowotny, H. (1989b) 'Mind, Technologies, and Collective Time Consciousness', in J. T. Fraser (ed.) Time and Mind, The Study of Time VI, pp. 197-216. Madison, CT: International Universities Press.

-