How a Collaborative Zettelkasten Might Work: A Modest Proposal for a New Kind of Collective Creativity by [[Bob Doto]]

Sounds a lot like the group wiki of the IndieWeb

How a Collaborative Zettelkasten Might Work: A Modest Proposal for a New Kind of Collective Creativity by [[Bob Doto]]

Sounds a lot like the group wiki of the IndieWeb

For Otlet, one of the major advantages of the UDC over alphabetical systemswas that “every alphabetical filing scheme has, through the arbitrariness of thechoice of words, a personal character, whereas the [U]DC has an impersonaland universal character” [6, p. 380].

alphabetical order vs. "semantic order" (by which I mean ordering ideas based on their proximity to each other in an area or sub-area of expertise)

No less important, the numerical notation served to “translateideas” into “universally understood signs,” namely numbers [13, p. 34].

Unlike Luhmann's numbers which served only as addresses, Paul Otlet's numbers were intimately linked to subject headings and became a means of using them across languages to imply similar meanings.

Whereas Otlet and Kaiser were in substantial agreement on both thedesirability of information analysis and its technological implementation inthe form of the card system, they parted company on the question of howindex files were to be organized. Both men favored organizing informationunits by subject, but differed as to the type of KO framework that shouldgovern file sequence: Otlet favored filing according to the classificatory orderof the UDC, whereas Kaiser favored filing according to the alphabeticalorder of the terms used to denote subjects

Compare the various organizational structures of Otlet, Kaiser, and Luhmann.

Seemingly their structures were dictated by the number of users and to some extent the memory of those users with respect to where to find various things.

Otlet as a multi-user system with no single control mechanism or person, other than the decimal organizing standard (in his case a preference for UDC), was easily flexible for larger groups. Kaiser's system was generally designed, built and managed by one person but intended for use by potentially larger numbers of people. He also advised a conservative number of indexing levels geared toward particular use-cases (that is a limited number of heading types or columns/rows from a database perspective.) Finally, Luhmann's was designed and built for use by a single person who would have a more intimate memory of a more idiosyncratic system.

How a Collaborative Zettelkasten Might Work: A Modest Proposal for a New Kind of Collective Creativity

Wörgötter, Michael. “Schriftenkartei [Typeface Index], 1958–1971.” Photo sharing social website. Flickr, 2023. https://www.flickr.com/photos/letterformarchive/albums/72177720310834741. License: Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/

Found via: Coles, Stephen. “This Just In: Schriftenkartei, a Typeface Index.” Letterform Archive, November 3, 2023. https://letterformarchive.org/news/schriftenkartei-german-font-index/.

At the time of their printing, only the members of West Germany’s National Printing Association could buy the cards. The circulation is estimated at fewer than 400 copies. Of these, only four were known to exist in publicly accessible collections, all in Germany — until now.

All seven of West Germany's metal type foundries collaborated to create a card index catalog (Schriftenkartei) of their typefaces. These included Bauersche Gießerei, H. Berthold AG, Genzsch & Heyse, Ludwig & Mayer, D. Stempel AG, Johannes Wagner GmbH, and C. E. Weber.

Fewer than 400 copies of the card index were available for purchase by members of West German's National Printing association.

I wonder what you think of a distinction between the more traditional 'scholar's box', and the proto-databases that were used to write dictionaries and then for projects such as the Mundaneum. I can't help feeling there's a significant difference between a collection of notes meant for a single person, and a collection meant to be used collaboratively. But not sure exactly how to characterize this difference. Seems to me that there's a tradition that ended up with the word processor, and another one that ended up with the database. I feel that the word processor, unlike the database, was a dead end.

reply to u/atomicnotes at https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/16njtfx/comment/k1tuc9c/?utm_source=reddit&utm_medium=web2x&context=3

u/atomicnotes, this is an excellent question. (Though I'd still like to come to terms with people who don't think it acts as a knowledge management system, there's obviously something I'm missing.)

Some of your distinction comes down to how one is using their zettelkasten and what sorts of questions are being asked of it. One of the earliest descriptions I've seen that begins to get at the difference is the description by Beatrice Webb of her notes (appendix C) in My Apprenticeship. As she describes what she's doing, I get the feeling that she's taking the same broad sort of notes we're all used to, but it's obvious from her discussion that she's also using her slips as a traditional database, but is lacking modern vocabulary to describe it as such.

Early efforts like the OED, TLL, the Wb, and even Gertrud Bauer's Coptic linguistic zettelkasten of the late 1970s were narrow enough in scope and data collected to make them almost dead simple to define, organize and use as databases on paper. Of course how they were used to compile their ultimate reference books was a bit more complex in form than the basic data from which they stemmed.

The Mundaneum had a much more complex flavor because it required a standardized system for everyone to work in concert against much more freeform as well as more complex forms of collected data and still be able to search for the answers to specific questions. While still somewhat database flavored, it was dramatically different from the others because of it scope and the much broader sorts of questions one could ask of it. I think that if you ask yourself what sorts of affordances you get from the two different groups (databases and word processors (or even their typewriter precursors) you find even more answers.

Typewriters and word processors allowed one to get words down on paper quicker by a magnitude of order or two faster, and in combination with reproduction equipment, made it easier to spin off copies of the document for small scale and local mass distribution a lot easier. They do allow a few affordances like higher readability (compared with less standardized and slower handwriting), quick search (at least in the digital era), and moving pieces of text around (also in digital). Much beyond this, they aren't tremendously helpful as a composition tool. As a thinking tool, typewriters and word processors aren't significantly better than their analog predecessors, so you don't gain a huge amount of leverage by using them.

On the other hand, databases and their spreadsheet brethren offer a lot more, particularly in digital realms. Data collection and collation become much easier. One can also form a massive variety of queries on such collected data, not to mention making calculations on those data or subjecting them to statistical analyses. Searching, sorting, and making direct comparisons also become far easier and quicker to do once you've amassed the data you need. Here again, Beatrice Webb's early experience and descriptions are very helpful as are Hollerinth's early work with punch cards and census data and the speed with which the results could be used.

Now if you compare the affordances by each of these in the digital era and plot their shifts against increasing computer processing power, you'll see that the value of the word processor stays relatively flat while the database shows much more significant movement.

Surely there is a lot more at play, particularly at scale and when taking network effects into account, but perhaps this quick sketch may explain to you a bit of the difference you've described.

Another difference you may be seeing/feeling is that of contextualization. Databases usually have much smaller and more discrete amounts of data cross-indexed (for example: a subject's name versus weight with a value in pounds or kilograms.) As a result the amount of context required to use them is dramatically lower compared to the sorts of data you might keep in an average atomic/evergreen note, which may need to be more heavily recontextualized for you when you need to use it in conjunction with other similar notes which may also need you to recontextualize them and then use them against or with one another.

Some of this is why the cards in the Thesaurus Linguae Latinae are easier to use and understand out of the box (presuming you know Latin) than those you might find in the Mundaneum. They'll also be far easier to use than a stranger's notes which will require even larger contextualization for you, especially when you haven't spent the time scaffolding the related and often unstated knowledge around them. This is why others' zettelkasten will be more difficult (but not wholly impossible) for a stranger to use. You might apply the analogy of context gaps between children and adults for a typical Disney animated movie to the situation. If you're using someone else's zettelkasten, you'll potentially be able to follow a base level story the way a child would view a Disney cartoon. Compare this to the zettelkasten's creator who will not only see that same story, but will have a much higher level of associative memory at play to see and understand a huge level of in-jokes, cultural references, and other associations that an adult watching the Disney movie will understand that the child would completely miss.

I'm curious to hear your thoughts on how this all plays out for your way of conceptualizing it.

Well one obvious drawback is that zettelkästen is not a knowledge management system.

reply to u/glugolly at https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/16njtfx/comment/k1fn8w4/?utm_source=reddit&utm_medium=web2x&context=3 and

Well, Zettelkasten is not a knowledge management system. [...] Update: I mean digital ZK. Shoe-box ZK is a combination of knowledge management system of that time and "thought system" of Niklas Luhmann. u/Aponogetone at https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/16njtfx/comment/k1f23nj/?utm_source=reddit&utm_medium=web2x&context=3

I'm curious to see some evidence for why both you and u/Aponogetone say that a slip box (analog, digital or otherwise) is not a knowledge management system? Perhaps you don't think of it that way or use it solely to that end, but I find it difficult to see in light of the way I use mine and others have in the past. I suspect that if I had access to either of yours I could use it as a knowledge management system and it would tell me a lot about your interests and what you know and with a bit of work I could continue using it as one.

Even an argument against the more encompassing group nature versus personal or individual knowledge management systems is blunted by the use of a Zettelkasten by Adler, Hutchins, et al. to create the Syntopicon, the group uses by the Mundaneum effort (which went to great lengths to standardize information to be findable), the Oxford English Dictionary compilation, Thesaurus Linguae Latinae (TLL), Wörterbuch der ägyptischen Sprache, or even the academics who still use photocopies or microfilm versions of S.D. Goitein's zettelkasten.

What are the rest of us missing in your argument?

Although Diller generated a lot of her own material, she elicited some gags from other writers. One of her top contributors was Mary MacBride, a Wisconsin housewife with five children. A joke obtained from another writer includes the contributor’s name on the index card with the gag.

Not all of the jokes in Phyllis Diller's collection were written by her. Many include comic strips she collected as well as jokes written by others and sent in to her.

One of the biggest contributors to her collection of jokes was Wisconsin housewife Mary MacBride, the mother of five children. Jokes contributed by others include their names on the individual cards.

Benefits of sharing permanent notes .t3_12gadut._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postBodyLink-VisitedLinkColor: #989898; }

reply to u/bestlunchtoday at https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/12gadut/benefits_of_sharing_permanent_notes/

I love the diversity of ideas here! So many different ways to do it all and perspectives on the pros/cons. It's all incredibly idiosyncratic, just like our notes.

I probably default to a far extreme of sharing the vast majority of my notes openly to the public (at least the ones taken digitally which account for probably 95%). You can find them here: https://hypothes.is/users/chrisaldrich.

Not many people notice or care, but I do know that a small handful follow and occasionally reply to them or email me questions. One or two people actually subscribe to them via RSS, and at least one has said that they know more about me, what I'm reading, what I'm interested in, and who I am by reading these over time. (I also personally follow a handful of people and tags there myself.) Some have remarked at how they appreciate watching my notes over time and then seeing the longer writing pieces they were integrated into. Some novice note takers have mentioned how much they appreciate being able to watch such a process of note taking turned into composition as examples which they might follow. Some just like a particular niche topic and follow it as a tag (so if you were interested in zettelkasten perhaps?) Why should I hide my conversation with the authors I read, or with my own zettelkasten unless it really needed to be private? Couldn't/shouldn't it all be part of "The Great Conversation"? The tougher part may be having means of appropriately focusing on and sharing this conversation without some of the ills and attention economy practices which plague the social space presently.

There are a few notes here on this post that talk about social media and how this plays a role in making them public or not. I suppose that if I were putting it all on a popular platform like Twitter or Instagram then the use of the notes would be or could be considered more performative. Since mine are on what I would call a very quiet pseudo-social network, but one specifically intended for note taking, they tend to be far less performative in nature and the majority of the focus is solely on what I want to make and use them for. I have the opportunity and ability to make some private and occasionally do so. Perhaps if the traffic and notice of them became more prominent I would change my habits, but generally it has been a net positive to have put my sensemaking out into the public, though I will admit that I have a lot of privilege to be able to do so.

Of course for those who just want my longer form stuff, there's a website/blog for that, though personally I think all the fun ideas at the bleeding edge are in my notes.

Since some (u/deafpolygon, u/Magnifico99, and u/thiefspy; cc: u/FastSascha, u/A_Dull_Significance) have mentioned social media, Instagram, and journalists, I'll share a relevant old note with an example, which is also simultaneously an example of the benefit of having public notes to be able to point at, which u/PantsMcFail2 also does here with one of Andy Matuschak's public notes:

[Prominent] Journalist John Dickerson indicates that he uses Instagram as a commonplace: https://www.instagram.com/jfdlibrary/ here he keeps a collection of photo "cards" with quotes from famous people rather than photos. He also keeps collections there of photos of notes from scraps of paper as well as photos of annotations he makes in books.

It's reasonably well known that Ronald Reagan shared some of his personal notes and collected quotations with his speechwriting staff while he was President. I would say that this and other similar examples of collaborative zettelkasten or collaborative note taking and their uses would blunt u/deafpolygon's argument that shared notes (online or otherwise) are either just (or only) a wiki. The forms are somewhat similar, but not all exactly the same. I suspect others could add to these examples.

And of course if you've been following along with all of my links, you'll have found yourself reading not only these words here, but also reading some of a directed conversation with entry points into my own personal zettelkasten, which you can also query as you like. I hope it has helped to increase the depth and level of the conversation, should you choose to enter into it. It's an open enough one that folks can pick and choose their own path through it as their interests dictate.

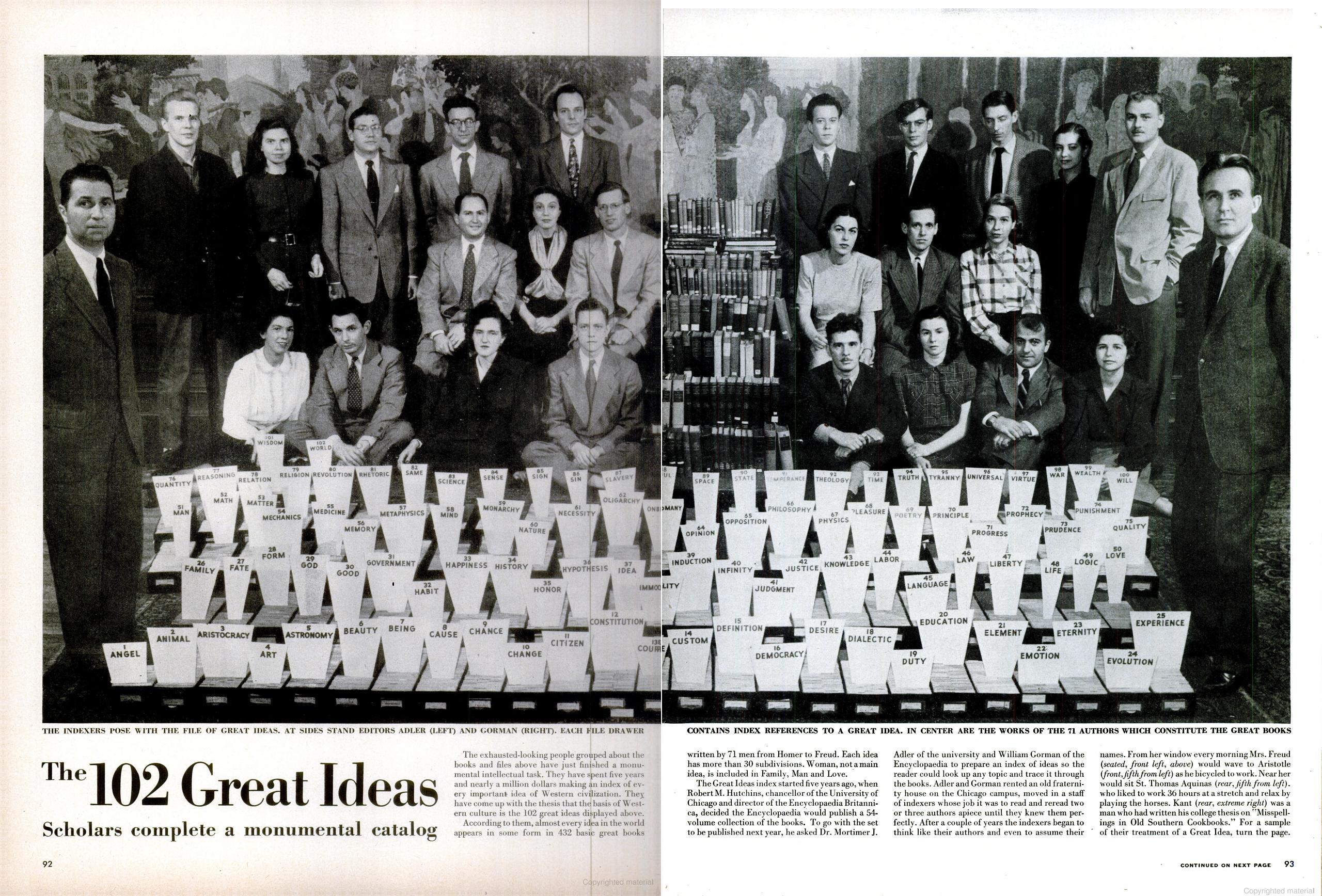

A staff of at least 26 created the underlying index that would lay at the heart of the Great Books of the Western World which was prepared in a rented old fraternity house on the University of Chicago campus. (p. 93)

TheSyntopicon invites the reader to make on the set whatever demands arisefrom his own problems and interests. It is constructed to enable the reader,nomatter what the stages of his reading in other ways, to find that part of theGreat Conversation in which any topic that interests him is being discussed.

While the Syntopicon ultimately appears in book form, one must recall that it started life as a paper slip-based card index (Life v24, issue 4, 1948). This index can be queried in some of the ways one might have queried a library card catalog or more specifically the way in which Niklas Luhmann indicated that he queried his zettelkasten (Luhmann,1981). Unlike a library card catalog, The Syntopicon would not only provide a variety of entry places within the Western canon to begin their search for answers, but would provide specific page numbers and passages rather than references to entire books.

The Syntopicon invites the reader to make on the set whatever demands arise from his own problems and interests. It is constructed to enable the reader, no matter what the stages of his reading in other ways, to find that part of the Great Conversation in which any topic that interests him is being discussed. (p. 85)

While the search space for the Syntopicon wasn't as large as the corpus covered by larger search engines of the 21st century, the work that went into making it and the depth and focus of the sources make it a much more valuable search tool from a humanistic perspective. This work and value can also be seen in a personal zettelkasten. Some of the value appears in the form of having previously built a store of contextualized knowledge, particularly in cases where some ideas have been forgotten or not easily called to mind, which serves as a context ratchet upon which to continue exploring and building.

Hypothesis Animated Intro, 2013. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QCkm0lL-6lc.

This was an early animation for Hypothes.is as a tool. It was on one of their early homepages and is (still) a pretty good encapsulation of what they do and who they are as a tool for thought.

The Wörterbuch der ägyptischen Sprache was an international collaborative zettelkasten project begun in 1897 and finally published as five volumes in 1926.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/W%C3%B6rterbuch_der_%C3%A4gyptischen_Sprache

In “collaboration with his Zettelkasten,”61 Blumenberg worked to por-tray these tensions between different and changing historical meanings ofscientific inquiry.

e called on his fellow rabbis to submitnotecards with details from their readings. He proposed that a central office gathermaterial into a ‘system’ of information about Jewish history, and he suggested theypublish the notes in the CCAR’s Yearbook.

This sounds similar to the variety of calls to do collaborative card indexes for scientific efforts, particularly those found in the fall of 1899 in the journal Science.

This is also very similar to Mortimer J. Adler et al's group collaboration to produce The Syntopicon as well as his work on Propædia and Encyclopædia Britannica.