Examine we our selves well, what we are: what we Church-members are

Call for self-reflection. Connects moral and spiritual vigilance to everyday behavior and participation in the church.

Examine we our selves well, what we are: what we Church-members are

Call for self-reflection. Connects moral and spiritual vigilance to everyday behavior and participation in the church.

There was a moment, in time, and in this place, when my brother, or my mother, or my father, or my sister, had to convey to me, for example, the danger in which I was standing from the white man standing just behind me, and to convey this with a speed, and in a language, that the white man could not possibly understand

What this shows: Communicative function of Black English for safety/solidarity; opacity to dominant listeners.

How I’ll connect it later: purpose-driven language (Baldwin) / Young’s claim that “It’s ATTITUDES,” not dialect deficits.

Subsequently, the slave was given, under the eye, and the gun, of his master, Congo Square, and the Bible — or, in other words, and under these conditions,.the slave began the formation of the black church, and it is within this unprecedented tabernacle that black English began to be formed.

Baldwin’s historical account of Black English’s formation complements Heller’s analysis of AAVE as identity/agency in Bambara—both center vernaculars as purposeful, not deficient.

Subsequently, the slave was given, under the eye, and the gun, of his master, Congo Square, and the Bible — or, in other words, and under these conditions,.the slave began the formation of the black church, and it is within this unprecedented tabernacle that black English began to be formed.

What this shows: Specific historical sites (church/community) where Black English coalesced.

How I’ll connect it later: historical formation (Baldwin) / AAVE-as-agency in literature (Heller).

It is not the black child's language that is in question, it is not his language that is despised: It is his experience.

Baldwin’s “it is his experience” aligns with Young’s language-justice stance and Alvarez/Wan/Lee’s translingual pedagogy—value lived experience and plural voice over monolingual “objectivity.”

It is not the black child's language that is in question, it is not his language that is despised: It is his experience.

Why this quote matters: Reframes “standards” as hostility to lived experience, not grammar.

Signal phrase I might use: Baldwin insists, “It is his experience.”

It is the most vivid and crucial key to identity: It reveals the private identity, and connects one with, or divorces one from, the larger, public, or communal identity.

Where Jenkins argues SAE mastery for workplace power, Baldwin reframes power as already embedded in Black English’s identity/politics—setting up a productive tension for synthesis.

It is the most vivid and crucial key to identity: It reveals the private identity, and connects one with, or divorces one from, the larger, public, or communal identity.

Why this quote matters: States language–identity linkage for synthesis. Signal phrase I might use: Baldwin maintains that language is “the most vivid and crucial key to identity…”

To start writing this chapter, for example, one of the first things we didwas read previous contributions to Writing Spaces to get a sense of the ex-pected tone and the structure.

What the example demonstrates: Audience/design analysis as part of language-architect work.

How I will connect it later: situational design (Alvarez/Wan/Lee) / Jenkins’s emphasis on audience expectations (contrast in aims).

Once we havesome words, ideas, frustrations on paper, we give ourselves small writingtasks, like “just write whatever you can or feel about X topic for 5 minutes.”

Pedagogy in action: The authors’ translingual strategies (freewriting, revision cycles) complement Young’s call to teach descriptively and embrace code meshing in the same paper.

Once we havesome words, ideas, frustrations on paper, we give ourselves small writingtasks, like “just write whatever you can or feel about X topic for 5 minutes.”

What the example demonstrates: A concrete technique that surfaces authentic voice before later shaping.

How I will connect it later: practice-level support for translingual composing / Young’s classroom stance on descriptive teaching.

What we mean bythis is that your voice and all the ways you use it—as part of who you are—makes all the difference, and therefore, should be amplified and cultivated.

Why this quote matters to my theme: Centers student voice as a positive resource to develop, not suppress.

Signal phrase I might use: The chapter emphasizes that “your voice… should be amplified and cultivated.”

Yes, you read this correctly: standard written English is not an objectiveset of criteria.

Standard vs. plurality: This chapter challenges the “objective” status of standard written English, contrasting with Jenkins’s claim that mastering a single standard is central to professional success.

Yes, you read this correctly: standard written English is not an objectiveset of criteria.

Why this quote matters to my theme: Directly challenges “objective standard” myths that drive gatekeeping.

Signal phrase I might use: The authors assert, “standard written English is not an objective set of criteria.”

Teachers frequently encounter him on panels with titles like“The Expanding Canon: Teaching Multicultural Literature InHigh School.” But the dude is also hella down to earth.

Vernacular as agency: Young’s code meshing aligns with Heller’s claim that AAVE conveys identity, confidence, and critique; both position vernacular forms as tools of voice and resistance.

Teachers frequently encounter him on panels with titles like“The Expanding Canon: Teaching Multicultural Literature InHigh School.” But the dude is also hella down to earth.

What the example demonstrates: Journalistic prose mixing formal description with vernacular insertions—live code meshing in print.

How I will connect it later: identity/voice via vernacular (Young) / AAVE-as-agency (Heller).

(1) Iowa Republican Senator Chuck Grassley sent two tweets to President Obamain June 2009 (Werner).

Pragmatics vs. plurality: Young promotes blending codes in public/professional writing (e.g., Grassley tweets), while Jenkins urges mastery of a single standard for workplace credibility.

(1) Iowa Republican Senator Chuck Grassley sent two tweets to President Obamain June 2009 (Werner).

What the example demonstrates: Public, professional communication already blends registers/abbreviations—evidence of code meshing beyond classrooms.

How I will connect it later: real-world register mixing (Young) / workplace register expectations (Jenkins).

Instead of prescribing how folks should write or speak, I say we teach languagedescriptively.

Why this quote matters to my theme: Sets the teaching stance that supports code meshing.

Signal phrase I might use: Young proposes, “we teach language descriptively.”

But dont nobody’s language, dialect, or style make them “vulnerable to preju-dice.” It’s ATTITUDES.

Why this quote matters to my theme: Reframes “deficits” as listener prejudice, not speaker dialect.

Signal phrase I might use: Young contends, “It’s ATTITUDES.”

"Who are these people that spend that much for performing clowns and $1,000 for toy sailboats? What kinda work they do and how they live and how come we ain't in on it?" (94).

What the example demonstrates: AAVE voice frames incisive social/economic questioning at the story’s climax.

How I will connect it later: AAVE questioning/critique (Heller) / Jenkins’s workplace-norms argument (contrast).

In the opening sentence of "The Lesson," Bambara clearly indicates that Sylvia is narrating in AAVE. Here, Sylvia describes Miss Moore as an adult with "nappy hair" (87).

Identity/agency: Heller’s framing of AAVE as pride and resistance aligns with Lysicott’s argument that vernacular resources carry identity and should be leveraged within academic spaces.

In the opening sentence of "The Lesson," Bambara clearly indicates that Sylvia is narrating in AAVE. Here, Sylvia describes Miss Moore as an adult with "nappy hair" (87).

What the example demonstrates: Early lexical cue grounds narrator’s voice in AAVE and signals cultural stance.

How I will connect it later: AAVE as identity marker (Heller) / code-meshing/voice (Lysicott).

Such writing implies resistance to the dominant culture, destabilizes the privileged dialect/discourse, and portrays "subversive voices" that present "alternative versions of reality" (11, 13, 46).

Why this quote matters to my theme: Captures the resistance function of dialect literature and aligns with Bambara’s use of AAVE.

Signal phrase I might use: Heller, citing Jones, notes that dialect writing “destabilizes the privileged dialect/discourse…”

However, Bambara also celebrates AAVE as a vehicle for conveying black experience: Sylvia uses AAVE to express her self-confidence, assertiveness, and creativity as a young black woman.

Why this quote matters to my theme: Names AAVE’s expressive and identity-affirming functions directly.

Signal phrase I might use: According to Heller, “Bambara also celebrates AAVE as a vehicle for conveying black experience…”

In short, standard American English is not inherently racist. It is not merely a “tool of the patriarchy.” It is a tool for anyone who wishes to use it

Why this quote matters to my theme: It directly rebuts claims that SAE is inherently discriminatory and frames it as an open tool.

Signal phrase I might use: Jenkins concludes, “In short, standard American English is not inherently racist…”

Later that day I received a reply from a young bank employee offering further details. Actually, I have no idea if she was young — I just assumed she was because her long e-mail was full of emoticons and text-messaging abbreviations — including, I kid you not, “LOL.”

Gatekeeping vs. pragmatics: Jenkins frames SAE as practical for credibility with unknown audiences, while Young critiques “Standard English” as gatekeeping that marginalizes nonstandard varieties. (Used for concept-map edge between Jenkins / Young.)

Later that day I received a reply from a young bank employee offering further details. Actually, I have no idea if she was young — I just assumed she was because her long e-mail was full of emoticons and text-messaging abbreviations — including, I kid you not, “LOL.”

What the example demonstrates: Informal dialect/features can undermine perceived professionalism and lead to lost business.

How I will connect it later: workplace expectations for tone/register (Jenkins) / critique of gatekeeping (Young).

In one class, my 24 students spoke 17 languages. I can tell you from experience that those students were eager to master standard American English — once I explained to them what it is (and isn’t) and how it could benefit them. They saw it as a key that could unlock the world of higher-paying employment.

What the example demonstrates: Multilingual students treat SAE as economic access and actively pursue it.

How I will connect it later: access via SAE (Jenkins) to/from identity/voice via code-meshing (Lysicott).

. In one class, my 24 students spoke 17 languages. I can tell you from experience that those students were eager to master standard American English — once I explained to them what it is (and isn’t) and how it could benefit them. They saw it as a key that could unlock the world of higher-paying employment.

Access vs. identity: Jenkins emphasizes SAE as a key to employment, while Lysicott foregrounds code-meshing to honor identity and agency within academic/professional spaces. (Used for concept-map edge between Jenkins/Lysicott.)

The only purpose of language is to communicate, and if the language or dialect you use in a particular situation allows you to do so, then it is effective.

Why this quote matters to my theme: It centers communication effectiveness as the standard, supporting SAE as situationally pragmatic.

Signal phrase I might use: According to Jenkins, “The only purpose of language is to communicate…”

The snapport is the area of the scroll container to which the snap areas are aligned. By default, it is the same as the visual viewport of the scroll container, but it can be adjusted using the scroll-padding property.

From what I understood of the theory is about how people see themselves on who they want to be, and how they feel about that difference such as self image and to find out who they wanna be and even with their self esteem

Concept. The term “concept” has differing meanings in various contexts(psychology, linguistics, philosophy). I am using “concept” as an abstractionthat does not reference a thing; rather, a concept establishes a boundary in afield of meaning. One might say that concepts are agreed-upon set bound-aries.

for - adjacency - concept - boundary

Sovereignty is a political concept that refers to dominant power or supreme authority. In modern democracies, sovereign power rests with the people and is exercised through representative bodies such as Congress or Parliament.

Sovereignty concept

Transdisciplinary sustainability science is increasingly applied to study transformative change. Yet, transdisciplinary research involves diverse actors who hold contrasting and sometimes conflicting perspectives and worldviews. Reflexivity is cited as a crucial capacity for navigating the resulting challenges

for - adjacency - reflexivity - tool for transdisciplinary research - indyweb - people-centered interpersonal information architecture - mindplex - concept spaces - perspectival knowing - life situatedness - SRG transdisciplinary complexity mapping tool - SOURCE - paper - Reflexivity as a transformative capacity for sustainability science: introducing a critical systems approach - Lazurko et al. - 2025, Jan 10

adjacency - between - reflexivity - tool for transdisciplinary research - indyweb - people-centered, interpersonal information architecture - mindplex - concept space - perspectival knowing - life situatedness - SRG transdisciplinary complexity mapping tool - adjacency relationship - This paper is interesting from the perspective of development of the Indyweb because there, - the people-centered, interpersonal information architecture intrinsically explicates perspectival knowing and life-situatedness - Indyweb can embed an affordance that is a meta function applied to an indyvidual's mindplex that - surfaces and aspectualizes the perspective and worldview salient to the research - The granular information that embeds an indyvidual's perspectives and worldviews is already there in the indyvidual's rich mindplex

the soul functions through pure synchronicity

Novel concept the soul functions through pure synchronicity

hy military masculinities are the sites where boundary-making activity takes place, and Belkin suggests that it may be because nation-states and militaries are closely tied, and the military occupies an important symbolic position in nation-states.

Here they suggest that along with thwarted masculinity, and vulnerable and stigmatized positionalities, men in conflict settings do not uniformly benefit from patriarchal structures and the gender order

doesnt show that some men dont benefit from the patriarchy

Not everyone has time to adhere to the specific coding styles for a project, so if you can't do a full blown pull-request, there is NOTHING wrong with opening a pull-request that only has the intention of showing the author how you solved the problem.

we know from Lab studies that children understand the meaning of stuff at first or second or third site you

for - neuroscience - children's understanding - 3 examples is enough to consolidate new concept

Socrates thought that self-understanding was essential to knowing how to live, and how to live well with oneself and with others.

Self-determination

What is self-determination? The prrocess of self understanding?

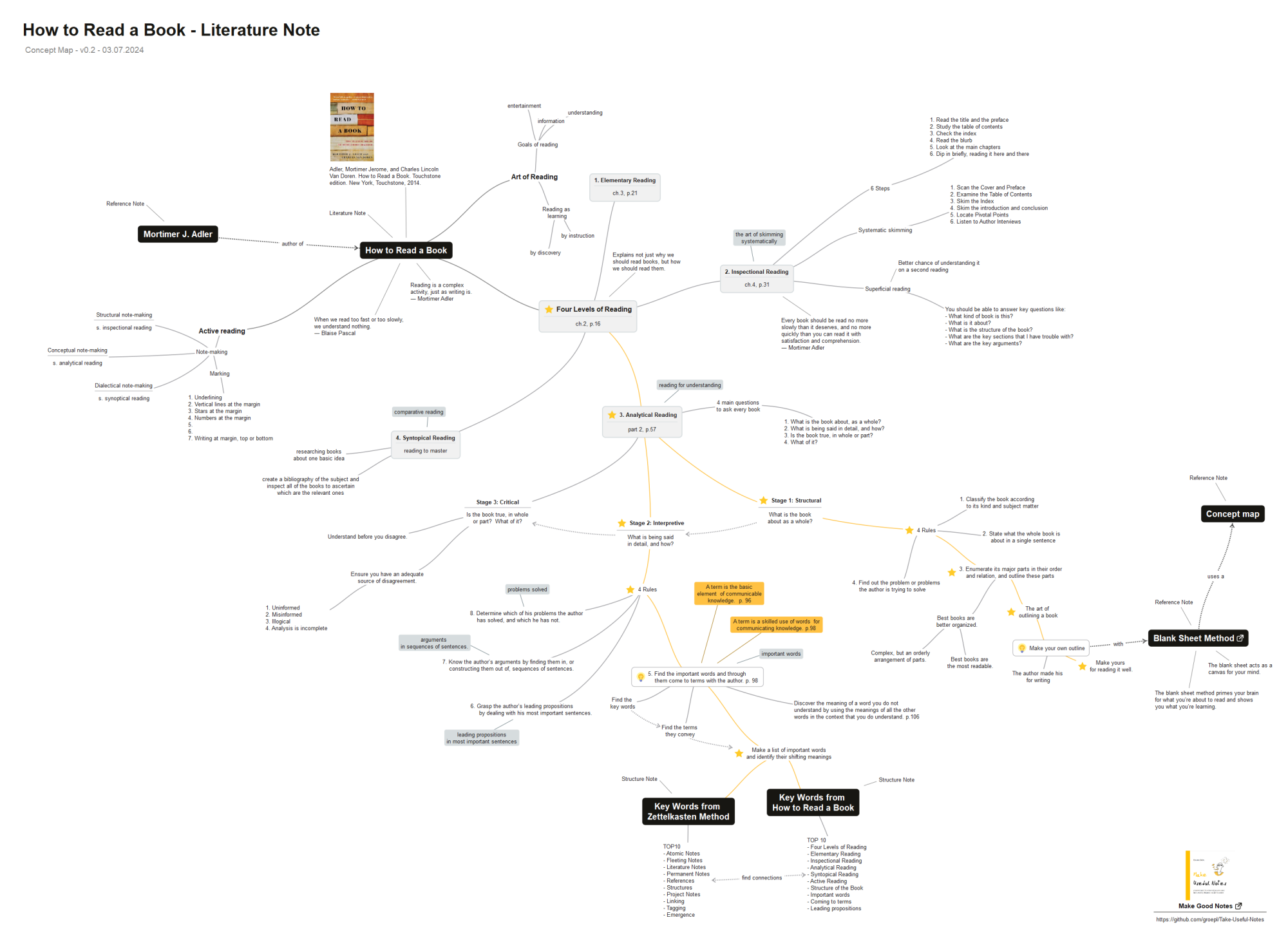

Adler, Mortimer J., and Charles Van Doren. How to Read a Book: The Classical Guide to Intelligent Reading. Revised and Updated edition. 1940. Reprint, Touchstone, 2011.

Edmund Gröpl's concept map of Adler & Van Doren's How to Read a Book via https://forum.zettelkasten.de/discussion/comment/20668#Comment_20668:

So she's this character who exists and is a film character. So film characters are, uh, glowing and luminous and they're perfect, right. They--they were born exactly as they should be. And I think that, uh, that's why we all show up to the movies. Because we get to experience characters in its most, uh, fundamental, uh, self.SONG 00:26:45So what we're pursuing is that, right. We're not trying to recreate the--you know, we're not making a docu series about it, you know. I mean it's so much more about it. So I think, and I think that process is happening for every single character.

concept development

And her soul and her heart. And her emotions. And talking through and building this character together. So I think that Nora is genuinely somewhere between part of me in our collaboration. I think she's the center of our collaboration. And she's not all Greta Lee, but also she's not all Celine Song.

collaborator actor concept development

Well, I think that it's because I am, uh, never quite thinking about the, uh, the characters as kind of an immolation of the real life people that the whole film was inspired by, right. So I'm never showing up to a conversation with Greta and saying it's like, well, because the character of Nora was inspired by who I am, you need to now be just like me. That's not what I'm asking her for.

concept development, actor

SONG 00:18:33Yeah. (laugh) Well, and well I think that it's also like, but I think when you're in a marriage too, I think that's the other side of things too. If you're--if you're in a long term relationship or a marriage like people--my audience members who, uh, have--who are in that place in their life.SONG 00:18:48You know, like it's sort of this other reaction where it's like, on one hand I've heard them say, you know, I just actually, uh, this movie made me, uh, really appreciate and love and acknowledge the--the importance of my partner. And I just how much I appreciate them, how excited I'm, um, you know, I feel, uh, to commit to them for the rest of my life.SONG 00:19:09And it just made me realize that I'm with a really, really good partner who cares for me, and I care for them. On the other side of things, I've also wrote the version of they're like, you know man, like this movie made me realize I'm in a very bad relationship. And I have a very hard conversation to have with my partner.SONG 00:19:27So I think that in that way, it's like it is meant to be more of the reflective surface for the audience. It's a little bit more like, huh, this is the decision and this is the life that this character Nora made. What does it make you think? What does it make you feel?SONG 00:19:40And--and how do you feel about it? Have you felt this way before?

concept development

Can I tell you. Like after almost every screening, uh, you know, because what's amazing is like, you know, like and also the movie can mean something different for everyone. I think that we see, uh, what kind of a life and what kind of a choice that, uh, Nora is making, or Nora is choosing.SONG 00:17:40But the thing that, uh, it reveals usually in the audience is like what--where are they--where they are in their life. And what they're looking for and what they want from their life. And what they're choosing. So for example, I heard both ends of spectrum from people who are single.SONG 00:17:56Where, you know, if you're single then, you know, I heard both of the actions of like, you know, this movie, you know, made me want to go and fly to another country and try to see if I can reconnect with that person whose I've been really hung up on. And just see if there's something there.

concept development

SONG 00:14:44Well, I think that when you're trying to, uh, make something that is really personal and that pass on in this case a very real autobiographical, uh, element and it's actually, uh, the--kind of the initial thing that, you know, spawn the whole film.SONG 00:15:00Because of that I think you're right. It is very, uh, vulnerable. But also I think that there is some total, uh, joy in it too. Because I get to share something that I personally feel very deeply is what it is like to be a human being, uh, today and now and right here.SONG 00:15:16So I think that the truth is that the feeling of that really did overwhelm, uh, the any kind of like, uh, fear or vulnerability or anything like that. I think that I could find the courage to, uh, share the story because I knew that if the audience, uh, would just hear me out on the story, I think that they would be able to understand, um, and really--and listen beyond on understand.

concept

I could not have written it without knowing how it ends. I think the first thing I wrote was the very opening and then I wrote the scene at the bar leading into the final walk home. I always knew we were driving towards that ending. It’s meant to be a knife — you want the ending to be sharp.

concept

I think about the ways a movie is going to live inside of audiences really differently. I don’t think it makes sense to only inspire tears — I think it can inspire a sense of bliss, too. The movie can mean so many different things. A lot of people see Nora cry at the end of the film, and they feel so connected to her and they also cry.

concept

Double Happiness director Mina Shum looks back at what has — and hasn't — changed in this extended interview from The Filmmakers.7 years agoDuration 10:31Double Happiness director Mina Shum looks back at what has — and hasn't — changed in this extended interview from The Filmmakers.7 years agoArtsShare2:27PauseMute9:4210:31Toggle fullscreenShareLinkFacebookTwitterEmailEmbedDouble Happiness director

She talks about representation on screen in the end of this interview.

Double Happiness

0:51 Mina delves into the concept of leaving home and achieving independence, drawing from her own experiences of leaving home at eighteen. She aims to develop this theme as a model for young women, exploring the challenges and triumphs associated with stepping out on one's own

The film is the vehicle for the reuniting the three generations in (more or less) corporeal form. But Ruth, who is “halved,” has a problem with integrity, and nothing is quite as simple as it seems. As the film unfolds, she leads us in an equivocal inquiry into the shifty nature of memory and the documentary genre itself.

In the film, the narrative reunites three generations. The film explores the concept of "halved."

Given the already describedstrains on the Jews, the negative effect of the heat, and thegreat overloading of most of the cars, the Jews attemptedtime and again to break out of the parked train cars, asdarkness had already set in toward 7:30 p.m.

Withthe coming of deep darkness in the night, many Jews escapedby squeezing through the air holes after removing the barbedwire.

in which I emphasized that aliquidation of the Jews could not take place arbitrarily. Thelarger portion of Jews still present in the city consisted ofcraftsmen and their families. One simply could not do withoutthe Jewish craftsmen, because they were indispensable for themaintenance of the economy

The battalion commander claimed that he protestedbut was merely told by the operations officer and division�mmander that the German police could provide the cordonand leave the shooting to the Lithuanians.

after-the fact testimony, war crime trial and memory guilt?

Forthis first shooting of large numbers of Jewish women, the authorof the war diary felt the need to provide a justification. Theywere shot, he explained, "because they had been encounteredwithout the Jewish star during the roundup . . . . Also in Minskit has been discovered that especially Jewesses removed themarking from their clothing.

instructed continuously aboutthe political necessity of the measures.

The battalion arrived in Bialystok on July 5, and two days laterwas ordered to carry out a "thorough search of the city , , , forBolshevik commissars and Communists," The war diary entry of,the following day makes clear what this meant: "a search of theJewish quarter,"

Every member had to be careful, he advised, "toappear before the Slavic peoples as a master and show them thathe was a German.

they seemed to offerthe guarantee of completing one's alternative to regular militaryservice not only more safely but closer to home.

In 1938 and 1939, the Order Police expanded rapidly as theincreasing threat of war gave prospective recruits a furtherinducement. If they enlisted in the Order Police, the new youngpolicemen were exempted from conscription into the army.

After the Nazi regime was established in 1933, a "police army"(Armee der Landespolizei) of 56,000 men was created. Theseunits were stationed in barracks and given full military trainingas part of Germany's covert rearmament.

counterrevolutionaryparamilitary units known as the Freikorps

The Jews had instigatedthe American boycott that had damaged Germany,

. Ifit would make their task any easier, the men should rememberthat in Germany the bombs were falling on women and children.

Heidegger responds to this predicamentby proposing that there are, in fact, two modes of being-with-others in-the-world, one authentic and the other inauthentic. Predictably, the inauthenticmode consists in being lost in the “they.” The authentic mode, on the otherhand, consists in Dasein recovering its ownmost potentiality for Being, whichwas, from the start, “taken away by the Others.”

modes of being-with-others in-the-world

what’s at stake in distinguishing between a heroic theory of agency andLevinas’s agency of the host-age is the ethical relation itself.

Unit commanders subsequentlydistributed instructions on “The Art of Writing a Letter,” urgingsoldiers to write “manly, hard and clear letters.” Many impressionswere “best locked deep in the heart because they concern only sol-diers at the front . . . Anyone who complains and bellyaches is notrue soldier.

“Actuallythe impact of letters from the front, which had been regarded as ex-traordinarily important, has to be considered more than harmfultoday,” he noted: “soldiers are pretty blunt when they describe thegreat problems they are fighting under, the lack of winter gear . . .insufficient food and ammunition.”

From the perspective of the regime, lettersfrom the front served to justify the war and to bind together the na-tion in a common purpose. Military officials underscored the im-portance of writing home; letters from the battle front supplied “akind of spiritual vitamin” for the home front and reinforced its “at-titude and nerves.

In World War IIas in World War I, soldiers classified friends and foes in terms of rel-ative cleanliness, but in this conflict they were much more apt tomake sweeping judgments about the population and to rank peopleaccording to rigid biological hierarchies. Even the ordinary infan-tryman adopted a racialized point of view, so that “the Russians”the Germans had fought in 1914–1918 were transformed into anundifferentiated peril, “the Russian,” regarded as “dull,” “dumb,”“stupid,” or “depraved” and “barely humanlike.”

Lettersand photographs, and the effort to archive them, indicated the ex-tent to which soldiers deliberately placed themselves in world his-tory and adopted for themselves the heroicizing vantage of theThird Reich

In the letters, it is clear that he does not just influencethem as a propagandist would, but, on closer examination, servesas their mouthpiece.”

the simple act of writing or mailing a letter distin-guished Germans from Jews. The distinction affected the abilityof people in the war to bear witness, to send news, and to makesense of extraordinary events. It indicated the destruction of onecommunity of remembrance and the survival of another.

In time ofwar, families frequently established archives in order to documenttheir role in national history

In time of war and separation, the letters to andfrom soldiers serving on the front lines were precious signs of life.They were avowals of love and longings for home. They describedthe battlefield and conditions of military occupation and eventuallyprovided historians with crucial documents about popular attitudestoward the war and knowledge about the Holocaust.

With smuggled letters, private diaries,and secret archives, Jewish victims made enormous efforts to leavebehind accounts of the atrocities the Nazis were committing.

One Berliner “watched his fellow passengers as he trav-eled past the burning Fasenenstrasse synagogue between the S-Bahnstations Savignyplatz and Zoologischer Garten the next morning:‘only a few looked up to see out the window, shrugged their shoul-ders, and went back to their paper.

The cities are administeredby mayors and councilmen drawn from his movement. The govern-ments of the states and the state parliaments are in the hands ofparty members

recisely becauseGermans had begun to think in terms of Feindbilder, or “visions ofthe enemy,” Goebbels regarded exhibitions such as these a “fantas-tic success.”

feindbilder - an idea of an enemy, a created image

Setapart from the familiar social contexts of family, work, and school,the closed camp was designed to break down identifications withsocial milieus and to promote Entbürgerlichung (purging bourgeoiselements) and Verkameradshaftung (comradeship) as part of theprocess of Volkwerdung, “the making of the people,” as the pecu-liar idiom of National Socialism put it.

entbürgerlichung - purging bourgeois elements

verkameradshaftung - comradeship

volkwerdung - the making of the people

Emigration meant the dispersion of the archive of Jewishlife in Germany, scattering the traces of ancestors and the signs ofcollective history. While German “Aryans” were driving their an-cestries deep into Germany’s past, German Jews were cutting loosefrom their heritage.Racial Grooming • 141

on 30 January 1939, Hitler prophesied “the annihilation ofthe Jewish race in Europe” in the event that “international financeJewry” succeeded in “plunging the nations once more into a worldwar.”

apoliceman’s “perp book”: “a small selection” of photographs fea-tured photographs of the imprisoned physicians, lawyers, and otherprofessionals whose newly shaven heads created the “eternal sem-blances” by which Jews dissolved into criminals.1

Sühneleistung, or “atonement fine,” which a ministerial conferenceset at one billion marks. Jewish taxpayers were required to handover 20 percent of their total assets in four installments ending inAugust 1939.

sühneleistung- atonement fine

certainly indicated outrage at the brutality of theNazis but also astonishing unawareness of the generally depress-ing conditions in which Jews lived in the Third Reich. Gossiperswere basically passive, telling about but not intervening in dramaticevents.

Criticism of the disruption of publicorder was widespread, but should not be taken completely at facevalue. It undoubtedly veiled deeper moral objections that were oth-erwise difficult to articulate in Nazi Germany

Well-appointed homes were ransacked and formerly prominent cit-izens tormented because Jews were regarded as profiteers whosewealth and social standing mocked the probity of the Volksgemein-schaft; children and the elderly were terrorized because they were“the Jew” whose very existence threatened Germany’s moral, polit-ical, and economic revival

But the rapid and uni-form responses by local Nazis indicated a basic readiness and desireto carry out anti-Jewish actions

The vernacular tag, at least in Berlin, of Reichskristallnacht, or“night of shattered glass,” to designate what should be considered anationwide pogrom against more than 300,000 Germans Jews inNovember 1938, was inflected with sardonic humor, which mockedthe pretentiousness of Nazi vocabulary in which Reich-this andReich-that puffed up the historical moment of the regime

The requirement that Jews add “Sarah” or “Israel” to their legalnames in January 1938 made even more clear the aim of the Nazisto register Jews as a prelude to physical expulsion.

fears based on recollections of the general strikes in 1919and 1920 and gruesome stories about atrocities in the Russian civilwar. It also fortified the image of the Jew as an intractable, immedi-ate danger.

In the context of the Spanish CivilWar, which broke out in July 1936, the Moscow “show trials”against old Bolsheviks in August 1936, and the November 1936anti-Comintern pact between Germany and Japan, the Nazis persis-tently linked Germany’s Jews to the Communist threat.

most Germans welcomed legis-lation clarifying the position of Jews and hoped it would bring to anend the graffiti and broken windows of anti-Jewish hooliganism.

half-Jews and quarter-Jews carried both good and bad genes and therefore could not beregarded as completely Jewish. Gross and others argued that mixedJews would eventually be absorbed into the Aryan race if they wereprohibited from marrying each other.

Jewish men who were imagined to prey on Germanwomen: the gender of the Jewish peril was male, while Aryan vul-nerability was female

“What am I going to do?” won-dered Richard Tesch, an owner of a bakery in Ballendstedt’s mar-ketplace: “Israel has been buying goods from me for a long time.Am I supposed to no longer sell to him? And if I do it anyway, thenI’ve lost the other customers.

The acknowledgment that there was a fundamental differencebetween Germans and Jews revived much older superstitions hold-ing that physical contact with Jews was harmful or that Jewish mendefiled German women.

Neighbors in Wedding who remarkedthat “the Jews haven’t done anything to us” despised antisemitismbut upheld the separation between “us” and “them” at which itaimed.85 Custom and habit gave way to self-conscious and inhib-ited interactions structured by the unambiguous knowledge of race

The startling events of the spring of 1933, when more andmore Germans realized that they were not supposed to shop inJewish stores and when German companies felt compelled to fireJewish employees and remove Jewish businessmen from corporateboards, moved Germany quite some distance toward the ultimategoal of “Aryanizing” the German economy.

Public humiliations such as these depended on bystanders willing totake part in the spectacle. They accelerated the division of neigh-borhoods into “us” and “them.

As thousands of new converts joined the para-military units of the SA, whose numbers shot up ninefold from500,000 in January 1933 to 4.5 million one year later, the scale ofantisemitic actions expanded dramatically. Becoming a Nazi meanttrying to become an antisemite as well.

It was along this circuitry,in which Germans imagined themselves as the victims of Jews andother “back-stabbers,” that “self-love” could turn into lethal “other-hate.”

Anti-semitism did not arrive on the scene as something completely new,but it acquired much greater symbolic value when people associ-ated it with being German.

part of a larger struggle to protect what so many Ger-mans regarded as the wounded, bleeding body of the nation.

the Nazis considered theJewish threat to be “lethal” and active, a perspective that gavetheir assault on the Jews a sense of urgency and necessity that madeGerman citizens more willing to go along

The idea of normality had become racialized, so that entitlement tolife and prosperity was limited to healthy Aryans, while newly iden-tified ethnic aliens such as Jews and Gypsies, who before 1933had been ordinary German citizens, and newly identified biologicalaliens such as genetically unfit individuals and so-called “asocials”were pushed outside the people’s community and threatened withisolation, incarceration, and death.

one of the key purposes of popu-lar entertainment in the Third Reich: the creation of a commonlyshared culture to define Germans to one another and mark themoff from others.

s aresult, Victor Klemperer could repeatedly “run into” one of Hitler’sReichstag speeches. “I could not get away from it for an hour. Firstfrom an open shop, then in the bank, then from a shop again.”66Radio as well as film turned Nazism into spectacle.

Tacked onto the doorways of apartments, posters, labels, and badgesattested to the fact that nearly all residents belonged to the People’sWelfare or contributed to Winter Relief.

signaling you belonged, if you didnt participate you were probably suspected of being a subversive

Millions of people acquired new vocabularies, joined Nazi organi-zations, and struggled to become better National Socialists. Whatthe diaries and letters report on is not simply the large numberof conversions among friends and relatives but the individual en-deavor to become a Nazi.

Young people don’t walk anymore; they march.” “Ev-erywhere friends are professing themselves for Hitler.” To livein Nazi Germany, Ebermayer wrote, was to “become ever morelonely.”

“Hei hatte sagt, wer non ganz un gar nichwolle, vor dän in Deutschland keine Raum”—“he said there is noroom in Germany for people who simply refuse to take part.”

Hermann Aue “(very Left),” thoughtthe Nazis would be gone within a year, so he was inclined to stickwith the Social Democrats. But several Communists who had re-portedly joined a local SA group suspected that the Nazis would bearound for some time.

May 1933 phy-sicians in Bremen called for comprehensive legislation to enablethe state to sterilize genetically unfit people

Local Nazidoctors in Dortmund greeted “the new era” with an April 1933proposal to establish a municipal “race office” that on the basisof 80,000 files on schoolchildren would prepare a “racial archiveof the entire population of greater Dortmund.”

As early as July 1933,the Ministry of the Interior drew up legislation that authorized thesterilization of allegedly genetically unfit citizens.

“Law for the Protection of German Blood”of 15 September 1935, which prohibited Germans from marryingJews

The Ahnenpass enabled the Nazi regime to enforce the Septem-ber 1935 Nuremberg racial law

In September 1939, after the invasion of Po-land, unter uns became legally enforced Aryan space when a decreeprohibited Jews from owning or listening to radios;

Two days after the Day of Potsdam, the Nazis won passageof the Enabling Act. Supported by all the parties except the SocialDemocrats (Communist deputies had been banned), it provided thelegal framework for dictatorship

Thecalamity of the unexpected surrender, the “bleeding borders” re-drawn in the postwar settlement at Versailles, and the overwhelm-ing chaos of the inflation in the early 1920s were collective experi-ences that made the suffering of the nation more comprehensible.During the Weimar years, the people’s community denoted the be-leaguered condition Germans shared, while expressing the politicalunity necessary for national renewal.

In this case it was the Nuremberg Laws, which distinguished Ger-man citizens from Jewish noncitizens: “hunting down innocentpeople is expanded a thousand times,” he raged; “hate is sown amillionfold.”

The fact is that it is totally possible,” he carefully noted,“that the National Socialist state would use such a law to make it aduty for those without means and who are dependent on handoutsfrom the state to more or less ‘voluntarily’ take their lives.

The euthanasia “actions” anticipated the Holocaust. Figuringout by trial and error the various stages of the killing process, fromthe identification of patients to the arrangement of special trans-ports to the murder sites to the killings by gas in special chambersto the disposal of the bodies, and mobilizing medical experts whoworked in secret with a variety of misleading euphemisms to con-ceal their work

ventuallythe criminal charges that relatives threatened to bring against hos-pitals, the dismay of local townspeople who wondered why the pa-tients “are never seen again”—“in one south German village, peas-ant women refused to sell cherries to nurses from the local statehospital”—and finally, in August 1941, the open denunciation ofinvoluntary euthanasia by Clemens August von Galen, the Catholicbishop of Münster in Westphalia, prompted Hitler to order the spe-cial killing centers dismantled.

. The Nazis carried out involuntary euthanasia in order“to purge the handicapped from the national gene pool,” but war-time conditions gave the program legitimacy and cover.

he sterilization proceedings put the voices ofvictims into the historical record, an unusual occurrence in NaziGermany. Whether they were “pleading or imploring, beseechingor threatening, complaining or accusing, bitter or outraged, fright-ened or self-confident, resigned or enraged, oral or written, rhymedor unrhymed,” the appeals were generally free of the “condescend-ing” scientific language of biological racism

In Berchtesgarden, in southern Germany, schoolteachers an-notated the tables of ancestors prepared by schoolchildren andhanded them over to public-health officials

Most candidates for sterilization came from lower-classbackgrounds, and since it was educated middle-class men who weremaking normative judgments about decent behavior, they were bothmore vulnerable to state action and less likely to arouse sympathy

German legal com-mentators reassured the German public by citing U.S. programs asprecedents and quoting Oliver Wendell Holmes’s 1927 opinion,“three generations of imbeciles are enough”

The rou-tine intervention of the police in the corners of daily life of Germancitizens explains why the Gestapo assumed the “almost mythicalstatus as an all-seeing, all-knowing” creature that had placed itsagents throughout the land to overhear conversations in order toenforce political conformity

Run largely alongside the state justice and penal system, concen-tration camps became a dumping ground for Gemeinschaftsfremde,“enemies of the community,” who were to spend the rest of theirlives thrown away.

gemeinschaftsfremde - enemies of the community

“the police have theresponsibility to safeguard the organic unity of the German people,its vital energies, and its facilities from destruction and disintegra-tion.” This definition gave the police extremely wide latitude. Any-thing that did not fit the normative standards of the people’s com-munity or could be construed as an agent of social dissolutiontheoretically fell under the purview of the police.

However, crime could be reduced by removing the dan-gerous body, either by isolating “asocials” in work camps or bysterilizing genetically “unworthy” individuals. In the Nazi legal sys-tem, genetics replaced milieu as the point of origin of crime

“In the language used by both the Nazis and the sci-entists, this policy was called ‘Aufartung durch Ausmerzung,’”improvement through exclusion.

Aufartung durch Ausmerzung - improvement through exclusion.

heNazis responded to an intense desire for order in Germany in 1933.Fears of Communist revolutionaries mingled with more generalanxieties about crime and delinquency.

Did shesympathize a little bit with people who were not considered wor-thy? Perhaps so, because Gisela recalled the incident in postwar in-terviews; but other Germans continued to improve themselves bygrooming themselves as Aryans, sitting up straighter, filling out thetable of ancestors, and fitting in at the camps, which gave legiti-macy to the selection process that had created Gisela’s anxiety inthe first place

With the massive expansion of the Hitler Youthto include girls as well as boys, more than 765,000 young peoplehad the opportunity to serve in leadership roles. Many advancedin the ranks and received formal training and ideological instruc-tion in national academies such as the Reich Leadership School inPotsdam.

The Ministry of Education authorized the National So-cialist Teachers’ League to organize retraining camps in order to“equip,” as Rust put it, teachers with lesson plans in “heredity andrace”; an estimated 215,000 of Germany’s 300,000 teachers at-tended two-week retreats at fifty-six regional sites and two nationalcenters that mixed athletics, military exercises, and instruction.

Arbeitsdienstmänner worked together as a unit, marched toget-her, and relaxed together, an unending group existence designed topull together the people’s community.

We have to go with the times, even if thereare many, many things that we do not agree with. To swim againstthe current just makes matters worse.”

More thana third of the 1938 graduating class of the Athenaeum Gymnasiumin the north German city of Stade hoped to pursue a career as an of-ficer in the Wehrmacht or a youth leader in the Hitler Youth

The consciousness of generation, and the assumption thatold needed to be replaced with new, undoubtedly opened youngminds to the tenets of racial hygiene, which were repeatedly parsedin workshops and lectures.

the national sports competition organized by the Hit-ler Youth enrolled seven million boys and girls in 1939, twice asmany as in 1935, and provided opportunities to achieve distinc-tion.

Boththe Hitler Youth and the Reich Labor Service aimed to mix bour-geois and working-class youths in order to pull down social barriersto the formation of national race consciousness.

Enrollment for four years in theHitler Youth and then six months in the Reich Labor Service wasmade mandatory for boys in 1936 and for girls three years later

Nazi pedagogues extolled das Lager, “the camp,”as the privileged place where the “new generation was finding itsform.”

das lager - the training community camps for german children

Filled with photographs, graphs, and tables, thepropaganda of the Office for Racial Politics made the crucial dis-tinction between quantity and quality—Zahl und Güte—easy tounderstand. Unlike Streicher’s vulgar antisemitic newspaper, DerStürmer, the Neues Volk appeared to be objective, a sobering state-ment of the difficult facts of life

hiding behind objectivity. ppl saying things and being like well its just fact w/o the ability to double check

By the middle of 1937 the Office of Racial Politics hadtrained over 2,000 “racial educators,” who on the basis of an eight-week course in Berlin received a special speaker’s certificate enti-tling them to address Germans on population and race policy. Certi-fication was part of the effort to make German racism objective

Repeated references to the “false humanity”and “exaggerated pity” of the liberal era indicated exactly whatwas at stake: the need to prepare Germans to endorse what univer-sal or Christian ethics would regard as criminal activity.

What was necessary, he insisted, was to“recognize yourself” (“Erkenne dich selbst”), which meant identi-fying with the idealized portraits of new Germans and following thetenets of hereditary biology to find a suitable partner for marriage,to marry only for love, and to provide the Volk with healthy chil-dren.

new visual regime repeatedly in-troduced the German body, most often in portraits of sunnyathletes, large families, and marching soldiers, and sometimes bycontrast in juxtaposed close-up shots of misshapen, degenerate

vast network of Gemeinschaftslager or com-munity camps was established across Germany; at one point or an-other, most Germans passed through them. Alongside concentra-tion camps and killing camps, the training camps were fundamentalparts of the Nazi racial project.

gemeinschaftslager - community / training camps to educate germans on racial ideology

In November in Weimar, he promised that “if to-day there are still people in Germany who say: ‘We are not goingjoin your community, but stay just as we always have been,’ then Isay: ‘You will die off, but after you there will a young generationthat doesn’t know anything else!’”

brah

It was the modern, scientificworld of “ethnocrats” and biomedical professionals, not the anti-communist Freikorps veterans of the SA, who devised Ahnenpässeand certificates of genetic health and evaluated the genetic worth ofindividuals.

not exactly a bait and switch but somewhere along those lines, hitler gained loyalty by kicking out communism and then harnessed the goodwill to be like "you know what else we need to do"

But it also made demands on ordinary Germans, who neededto visualize the Volk as a vital racial subject, to choose appropriatemarriage partners, and to accept “limits to empathy.”

he Germanpopulation was being resorted according to supposed genetic val-ues, a project that required all Germans to reexamine their rela-tives, friends, and neighbors.

A wide rangeof public health-care professionals from doctors to nurses to social-welfare officers were enlisted in the effort to locate undesirables.

The journalistSebastian Haffner noted that people in his circle in Berlin suddenlyfelt authorized to express an opinion on the “Jewish question,”speaking fluently about quotas on Jews, percentages of Jews, anddegrees of Jewish influence

a ministerial committeeon “population and race,” which met on 28 June 1933 to draftcomprehensive racial legislation giving the state the right to sterilizecitizens

a domestic-sounding vocabulary; a rhetoric of “cleaning,” “sweeping clean,”“housecleaning” strengthened the tendency to see politics in thedrastic terms of friends and foes

Racial thinking presumed thatonly the essential sameness of the German ethnic community guar-anteed biological strength. For the Nazis, the goal of racial puritymeant excluding Jews, whom they imagined to be a racially alienpeople who had fomented revolution and civil strife and divided theGerman people.

In place of the quarrels of party, the contests of inter-est, and the divisions of class, which they believed compromised theability of the nation to act, the Nazis proposed to build a unified ra-cial community guided by modern science. Such an endeavor wouldprovide Germany with the “unity of action” necessary to surviveand prosper in the dangerous conditions of the twentieth century

. It drew up a long list of internaland external dangers that imperiled the nation. At the same time, itrested on extraordinary confidence in the ability of racial policy totransform social life.

cultivate racial solidarity by overcoming social divi-sions, prohibiting racial mixing, and combating degenerative bio-logical trends

In other words, biology appeared to provideGermany with highly useful technologies of renovation. The Na-zis regarded racism as a scientifically grounded, self-consciouslymodern form of political organization.

thousands of“ethnocrats” and other professionals mobilized to build the newbiomedical structures of the Third Reich. They oriented their ca-reers and ambitions toward the wide spaces that Nazi Germany’sracial vision had opened up.

Race defined the new realities of the ThirdReich for both beneficiaries and victims—it influenced how youconsulted a doctor, whom you talked to, and where you shopped.

As parents, educators, volunteers, and soldiers, millions of Ger-mans played new parts in cultivating Aryan identities and segregat-ing out unworthy lives. They did not always do so willingly, andthey certainly did not anticipate the final outcomes of total war andmass murder.

most Germans had little reason tothink of the Third Reich as particularly sinister. “It was possible tolive in Germany throughout the whole period of the dictatorship,”

More than ten mil-lion Germans obtained a certificate of genetic health, which wasnecessary in order to claim entitlements such as marriage loans.

until the very end of the Reich in 1945, they handedout hundreds of thousands of copies of the eight-mark “people’sedition” along with pamphlets providing advice on how to main-tain good racial stock and prepare Ahnenpässe, “Germans, HeedYour Health and Your Children’s Health,” “A Handbook for Ger-man Families,” and “Advice for Mothers.”

During the war Klemperer, like so manyother Jews, was forced to move into the drastically smaller quartersof a “Jew house,” which meant that he had to dispose of books andpapers. “[I] am virtually ravaging my past,” he wrote in his di-ary on 21 May 1941. “The principal activity” of the next daywas “burning, burning, burning for hours on end: heaps of letters,manuscripts.

nazis enforced the creation of aryan archives and forced the destruction of jewish ones, creating an imbalance in how much material there was in order to control the historical narrative

Family archives, racial categories, and individual identitiesbecame closely calibrated with one another over the course of theThird Reich

all the humor about Jewishness in Germany, the fear of stum-bling upon Jewish grandmothers and the relief when only a “Jewishgreat-grandmother,” “who cannot hurt you anymore,” turned up,did not dispel the suspicion that Jews were different.

the mandatory nature of the racial passport and the nuremberg laws about jewish blood in mixed lineage emphasized that being aryan was a good thing and allowed people with a small amount of jewish ancestry to develop antisemitic feelings towards jewish people

Significantly, thestate did not issue racial passports; Germans had to prepare thempersonally. They thus attained for themselves their racial status asAryans.

by motivating germans to trace ancestry for mandatory passports and inclusion in the community, they "legitimize" the feeling of racial connection and exclusivity

Whereas an Aryanidentity opened the way for a future in the Third Reich, a Jewishone closed it down.

By 1936 almost all Germans—all who were not Jewish—had begun to prepare for themselves an Ahnenpass, or racial pass-port, which laid the foundation for the racial archives establishedin all German households

the sheerforce of the imagery and the busy schedules of national acclamationmade dissent politically risky; but even more: dissent also appearedto be futile.

As a result, Germans could imagine one another infront of the radio listening to the same program: “Sunday isWunschkonzert,” wrote one soldier to his family back home; “youcertainly will be listening too.”

He believed Germans feltthat “it’s just us now” when they lived without Jews. “Just us” alsoexpressed the closed circle in which Germans could see and experi-ence “ourselves” as “we are” and as “we have become.”

With the cheerful slices of German life they broadcastand the national audience they pulled together, radio plays recrea-ted the people’s community. It produced the effect of being unteruns, “just us.”

unter uns - only us, (us referring to ethnic germans, the feeling of inclusion in a special group)

On these occasions, friends and neighbors knew they wouldfind one another in front of the radio and could later share im-pressions—in this sense, Gemeinschaftsempfang, collective recep-tion, had been achieved.

gemeinschaftsempfang - communal listening, the understanding that everything you hear is what everyone else is also hearing and the sense of solidarity you gain from it

In what it touted as the triumph of “socialism ofthe deed” over “private capitalism” and “economic liberalism,” in1933 the Propaganda Ministry pressed a consortium of radio man-ufacturers to design and produce a Volksempfänger, or “people’sradio,” for the mass market.

The eventfulness of the Day of Potsdam was the reason “all three,father, mother, and Emma” Dürkefälden, had gone to Kaune’s tav-ern, but it was also what they themselves produced by going there

self perpetuating / self fulfilling cycle-- by drawing in crowds, nazis could pass off the illusion of unanimous support and community among germans, national unity

Nazis wanted the Germanpeople to comprehend events on the order of grand history by hear-ing broadcasts on the radio, seeing the reassembly of marchers onfilm, and taking photographs of their own part in the making of thepeople’s community

Germans even went to warwith preprinted diaries that left space for snapshots. All this was anacknowledgment of the desire to be part of and to share the Ger-man history that was being made.

With banners, flags, marches, and “Heil Hitler!” the Nazis pro-duced a distinctive public choreography and accompanying soundtrack that seemed to affirm the unanimity of the people’s commu-nity.

Radio helped to create the collective voice of thenation.

Thus, for leading opponents of the Nazis, and for the Jews andother minorities that the regime tormented, there seemed to be littlealternative but to abandon Germany altogether. Since most exilesnever returned, Germany’s political and intellectual life continuedto be structured by the Nazis long after their defeat

lack of dissenting voices means nazis shape everything

but even then nothing made the “com-munity of fate” more compelling than “the conviction that therewill no longer be future for Germany after a lost war.”

sunk-cost fallacy-- they put so much investment into this, they can't back out

“Ifonly the good old days would come back again, just one more time.Why do we have to have this dreadful war, which has disrupted ourpeaceful lives, broken our happiness, and dissolved all our big andlittle hopes for a new house into nothing?”

But when the German cheers wouldnot stop, “Hitler sensed a popular mood, a longing for peace andreconciliation.” This was also an indication of the general content-ment with things as they were.