This is the full workflow diagram. First, each molecule has a universal adapter + sample barcode ligated to each 5' end. Then, only 1 strand of each molecule is amplified using GSP1 (which is pretty nonspecific amplification) and a universal adapter primer over 10 PCR cycles. The resulting molecules should have a PCR multiplexing tag on the end, I guess. Then, only 1 strand of each amplified molecule is amplified using GSP2 (which is super selective) and a universal adapter primer over 10-14 PCR cycles. The resulting molecules should have a second adapter sequence by the end. An indexing primer is then attached to the second adapter sequence of each molecule.

- Last 7 days

-

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Note: This response was posted by the corresponding author to Review Commons. The content has not been altered except for formatting.

Learn more at Review Commons

Reply to the reviewers

Reviewer #1 (Evidence, reproducibility and clarity (Required)):

Summary:

Damaris et al. perform what is effectively an eQTL analysis on microbial pangenomes of E. coli and P. aeruginosa. Specifically, they leverage a large dataset of paired DNA/RNA-seq information for hundreds of strains of these microbes to establish correlations between genetic variants and changes in gene expression. Ultimately, their claim is that this approach identifies non-coding variants that affect expression of genes in a predictable manner and explain differences in phenotypes. They attempt to reinforce these claims through use of a widely regarded promoter calculator to quantify promoter effects, as well as some validation studies in living cells. Lastly, they show that these non-coding variations can explain some cases of antibiotic resistance in these microbes.

Major comments

Are the claims and the conclusions supported by the data or do they require additional experiments or analyses to support them?

The authors convincingly demonstrate that they can identify non-coding variation in pangenomes of bacteria and associate these with phenotypes of interest. What is unclear is the extent by which they account for covariation of genetic variation? Are the SNPs they implicate truly responsible for the changes in expression they observe? Or are they merely genetically linked to the true causal variants. This has been solved by other GWAS studies but isn't discussed as far as I can tell here.

We thank the reviewer for their effective summary of our study. Regarding our ability to identify variants that are causal for gene expression changes versus those that only “tag” the causal ones, here we have to again offer our apologies for not spelling out the limitation of GWAS approaches, namely the difficulty in separating associated with causal variants. This inherent difficulty is the main reason why we added the in-silico and in-vitro validation experiments; while they each have their own limitations, we argue that they all point towards providing a causal link between some of our associations and measured gene expression changes. We have amended the discussion (e.g. at L548) section to spell our intention out better and provide better context for readers that are not familiar with the pitfalls of (bacterial) GWAS.

They need to justify why they consider the 30bp downstream of the start codon as non-coding. While this region certainly has regulatory impact, it is also definitely coding. To what extent could this confound results and how many significant associations to expression are in this region vs upstream?

We agree with the reviewer that defining this region as “non-coding” is formally not correct, as it includes the first 10 codons of the focal gene. We have amended the text to change the definition to “cis regulatory region” and avoided using the term “non-coding” throughout the manuscript. Regarding the relevance of this including the early coding region, we have looked at the distribution of associated hits in the cis regulatory regions we have defined; the results are shown in Supplementary Figure 3.

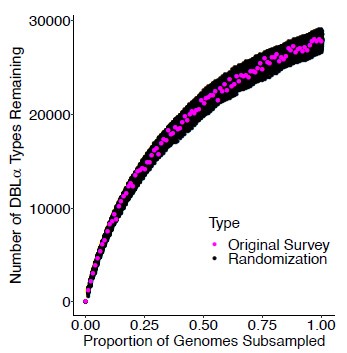

We quantified the distribution of cis associated variants and compared them to a 2,000 permutations restricted to the -200bp and +30bp window in both E. coli * (panel A) and P. aeruginosa* (panel B). As it can be seen, the associated variants that we have identified are mostly present in the 200bp region and the +30bp region shows a mild depletion relative to the random expectation, which we derived through a variant position shuffling approach (2,000 replicates). Therefore, we believe that the inclusion of the early coding region results in an appreciable number of associations, and in our opinion justify its inclusion as a putative “cis regulatory region”.

The claim that promoter variation correlates with changes in measured gene expression is not convincingly demonstrated (although, yes, very intuitive). Figure 3 is a convoluted way of demonstrating that predicted transcription rates correlate with measured gene expression. For each variant, can you do the basic analysis of just comparing differences in promoter calculator predictions and actual gene expression? I.e. correlation between (promoter activity variant X)-(promoter activity variant Y) vs (measured gene expression variant X)-(measured gene expression variant Y). You'll probably have to

We realize that we may not have failed to properly explain how we carried out this analysis, which we did exactly in the way the reviewer suggests here. We had in fact provided four example scatterplots of the kind the reviewer was requesting as part of Figure 4. We have added a mention of their presence in the caption of Figure 3.

Figure 7 it is unclear what this experiment was. How were they tested? Did you generate the data themselves? Did you do RNA-seq (which is what is described in the methods) or just test and compare known genomic data?

We apologize for the lack of clarity here; we have amended the figure’s caption and the corresponding section of the results (i.e. L411 and L418) to better highlight how the underlying drug susceptibility data and genomes came from previously published studies.

Are the data and the methods presented in such a way that they can be reproduced?

No, this is the biggest flaw of the work. The RNA-Seq experiment to start this project is not described at all as well as other key experiments. Descriptions of methods in the text are far too vague to understand the approach or rationale at many points in the text. The scripts are available on github but there is no description of what they correspond to outside of the file names and none of the data files are found to replicate the plots.

We have taken this critique to heart, and have given more details about the experimental setup for the generation of the RNA-seq data in the methods as well as the results sections. We have also thoroughly reviewed any description of the methods we have employed to make sure they are more clearly presented to the readers. We have also updated our code repository in order to provide more information about the meaning of each script provided, although we would like to point out that we have not made the code to be general purpose, but rather as an open documentation on how the data was analyzed.

Figure 8B is intended to show that the WaaQ operon is connected to known Abx resistance genes but uses the STRING method. This requires a list of genes but how did they build this list? Why look at these known ABx genes in particular? STRING does not really show evidence, these need to be substantiated or at least need to justify why this analysis was performed.

We have amended the Methods section (“Gene interaction analysis”, L799) to better clarify how the network shown in this panel was obtained. In short, we have filtered the STRING database to identify genes connected to members of the waa operon with an interaction score of at least 0.4 (“moderate confidence”), excluding the “text mining” field. Antimicrobial resistance genes were identified according to the CARD database. We believe these changes will help the readers to better understand how we derived this interaction.

Are the experiments adequately replicated and statistical analysis adequate?

An important claim on MIC of variants for supplementary table 8 has no raw data and no clear replicates available. Only figure 6, the in vitro testing of variant expression, mentions any replicates.

We have expanded the relevant section in the Methods (“Antibiotic exposure and RNA extraction”, L778) to provide more information on the way these assays were carried out. In short, we carried out three biological replicates, the average MIC of two replicates in closest agreement was the representative MIC for the strain. We believe that we have followed standard practice in the field of microbiology, but we agree that more details were needed to be provided in order for readers to appreciate this.

Minor comments

Specific experimental issues that are easily addressable..

Are prior studies referenced appropriately?

There should be a discussion of eQTLs in this. Although these have mostly been in eukaryotes a. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-024-01769-9 ; https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg3891.

We have added these two references, which provide a broader context to our study and methodology, in the introduction.

Line 67. Missing important citation for Ireland et al. 2020 https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.55308

Line 69. Should mention Johns et al. 2018 (https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.4633) where they study promoter sequences outside of E. coli

Line 90 - replace 'hypothesis-free' with unbiased

We have implemented these changes.

Line 102 - state % of DEGs relative to the entire pan-genome

Given that the study is focused on identifying variants that were associated with changes in expression for reference genes (i.e. those present in the reference genome), we think that providing this percentage would give the false impression that our analysis include accessory genes that are not encoded by the reference isolate, which is not what we have done.

Figure 1A is not discussed in the text

We have added an explicit mention of the panels in the relevant section of the results.

Line 111: it is unclear what enrichment was being compared between, FIgures 1C/D have 'Gene counts' but is of the total DEGs? How is the p-value derived? Comparing and what statistical test was performed? Comparing DEG enrichment vs the pangenome? K12 genome?

We have amended the results and methods section, as well as Figure 1’s caption to provide more details on how this analysis was carried out.

Line 122-123: State what letters correspond to these COG categories here

We have implemented the clarifications and edits suggested above

Line 155: Need to clarify how you use k-mers in this and how they are different than SNPs. are you looking at k-mer content of these regions? K-mers up to hexamers or what? How are these compared. You can't just say we used k-mers.

We have amended that line in the results section to more explicitly refer to the actual encoding of the k-mer variants, which were presence/absence patterns for k-mers extracted from each target gene’s promoter region separately, using our own developed method, called panfeed. We note that more details were already given in the methods section, but we do recognize that it’s better to clarify things in the results section, so that more distracted readers get the proper information about this class of genetic variants.

Line 172: It would be VERY helpful to have a supplementary figure describing these types of variants, perhaps a multiple-sequence alignment containing each example

We thank the reviewer for this suggestion. We have now added Supplementary Figure 3, which shows the sequence alignments of the cis-regulatory regions underlying each class of the genetic marker for both E. coli and P. aeruginosa.

Figure 4: THis figure is too small. Why are WaaQ and UlaE being used as examples here when you are supposed to be explicitly showing variants with strong positive correlations?

We rearranged the figure’s layout to improve its readability. We agree that the correlation for waaQ and ulaE is weaker than for yfgJ and kgtP, but our intention was to not simply cherry-pick strong examples, but also those for which the link between predicted promoter strength and recorded gene expression was less obvious.

Figure 4: Why is there variation between variants present and variant absent? Is this due to other changes in the variant? Should mention this in the text somewhere

Variability in the predicted transcription rate for isolates encoding for the same variant is due to the presence of other (different) variants in the region surrounding the target variant. PromoterCalculator uses nucleotide regions of variable length (78 to 83bp) to make its predictions, while the variants we are focusing on are typically shorter (as shown in Figure 4). This results in other variants being included in the calculation and therefore slightly different predicted transcription rates for each strain. We have amended the caption of Figure 4 to provide a succinct explanation of these differences.

Line 359: Need to talk about each supplementary figure 4 to 9 and how they demonstrate your point.

We have expanded this section to more explicitly mention the contents of these supplementary figures and why they are relevant for the findings of this section (L425).

Are the text and figures clear and accurate?

Figure 4 too small

We have fixed the figure, as described above

Acronyms are defined multiple times in the manuscript, sometimes not the first time they are used (e.g. SNP, InDel)

Figure 8A - Remove red box, increase label size

Figure 8B - Low resolution, grey text is unreadable and should be darker and higher resolution

Line 35 - be more specific about types of carbon metabolism and catabolite repression

Line 67 - include citation for ireland et al. 2020 https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.55308

Line 74 - You talk about looking in cis but don't specify how mar away cis is

Line 75 - we encoded genetic variants..... It is unclear what you mean here

Line 104 - 'were apart of operons' should clarify you mean polycistronic or multi-gene operons. Single genes may be considered operonic units as well.

We have addressed all the issues indicated above.

Figure 2: THere is no axis for the percents and the percents don't make sense relative to the bars they represent??

We realize that this visualization might not have been the most clear for readers, and have made the following improvement: we have added the number of genes with at least one association before the percentage. We note that the x-axis is in log scale, which may make it seem like the light-colored bars are off. With the addition of the actual number of associated genes we think that this confusion has been removed.

Figure 2: Figure 2B legend should clarify that these are individual examples of Differential expression between variants

Line 198-199: This sentence doesn't make sense, 'encoded using kmers' is not descriptive enough

Line 205: Should be upfront about that you're using the Promoter Calculator that models biophysical properties of promoter sequences to predict activity.

Line 251: 'Scanned the non-coding sequences of the DEGs'. This is far too vague of a description of an approach. Need to clarify how you did this and I didn't see in the method. Is this an HMM? Perfect sequence match to consensus sequence? Some type of alignment?

Line 257-259: This sentence lacks clarity

We have implemented all the suggested changes and clarified the points that the reviewer has highlighted above.

Line346: How were the E. coli isolates tested? Was this an experiment you did? This is a massive undertaking (1600 isolates * 12 conditions) if so so should be clearly defined

While we have indicated in the previous paragraph that the genomes and antimicrobial susceptibility data were obtained from previously published studies, we have now modified this paragraph (e.g. L411 and L418) slightly to make this point even clearer.

Figure 6A: The tile plot on the right side is not clearly labeled and it is unclear what it is showing and how that relates to the bar plots.

In the revised figure, we have clarified the labeling of the heatmap to now read “Log2(Fold Change) (measured expression)” to indicate that it represents each gene’s fold changes obtained from our initial transcriptomic analysis. We have also included this information in the caption of the figure, making the relationship between the measured gene expression (heatmap) and the reporter assay data (bar plots) clear to the reader.

FIgure 6B: typo in legend 'Downreglation'

We thank the review for pointing this out. The typo has been corrected to “Down regulation” in the revised figure.

Line 398: Need to state rationale for why Waaq operon is being investigated here. WHy did you look into individual example?

We thank the reviewer for asking for a clarification here. Our decision to investigate the waaQ gene was one of both biological relevance and empirical evidence. In our analysis associating non-coding variants with antimicrobial resistance using the Moradigaravand et al. dataset, we identified a T>C variant at position 3808241 that was associated with resistance to Tobramycin. We also observed this variant in our strain collection, where it was associated with expression changes of the gene, suggesting a possible functional impact. The waa operon is involved in LPS synthesis, a central determinant of the bacteria’s outer membrane integrity and a well established virulence factor. This provided a plausible biological mechanism through which variation could influence antimicrobial susceptibility. As its role in resistance has not been extensively characterized, this represents a good candidate for our experimental validation. We have now included this rationale in our revised manuscript (i.e. L476).

Figure 8: Can get rid of red box

We have now removed the red box from Figure 8 in the revised version.

Line 463 - 'account for all kinds' is too informal

Mix of font styles throughout document

We have implemented all the suggestions and formatting changes indicated above.

Reviewer #2 (Evidence, reproducibility and clarity (Required)):

In their manuscript "Cis non-coding genetic variation drives gene expression changes in the E. coli and P. aeruginosa pangenomes", Damaris and co-authors present an extensive meta-analysis, plus some useful follow up experiments, attempting to apply GWAS principles to identify the extent to which differences in gene expression between different strains within a given species can be directly assigned to cis-regulatory mutations. The overall principle, and the question raised by the study, is one of substantial interest, and the manuscript here represents a careful and fascinating effort at unravelling these important questions. I want to preface my review below (which may otherwise sound more harsh than I intend) with the acknowledgment that this is an EXTREMELY difficult and challenging problem that the authors are approaching, and they have clearly put in a substantial amount of high quality work in their efforts to address it. I applaud the work done here, I think it presents some very interesting findings, and I acknowledge fully that there is no one perfect approach to addressing these challenges, and while I will object to some of the decisions made by the authors below, I readily admit that others might challenge my own suggestions and approaches here. With that said, however, there is one fundamental decision that the authors made which I simply cannot agree with, and which in my view undermines much of the analysis and utility of the study: that decision is to treat both gene expression and the identification of cis-regulatory regions at the level of individual genes, rather than transcriptional units. Below I will expand on why I find this problematic, how it might be addressed, and what other areas for improvement I see in the manuscript:

We thank the reviewer for their praise of our work. A careful set of replies to the major and minor critiques are reported below each point.

In the entire discussion from lines roughly 100-130, the authors frequently dissect out apparently differentially expressed genes from non differentially expressed genes within the same operons... I honestly wonder whether this is a useful distinction. I understand that by the criteria set forth by the authors it is technically correct, and yet, I wonder if this is more due to thresholding artifacts (i.e., some genes passing the authors' reasonable-yet-arbitrary thresholds whereas others in the same operon do not), and in the process causing a distraction from an operon that is in fact largely moving in the same direction. The authors might wish to either aggregate data in some way across known transcriptional units for the purposes of their analysis, and/or consider a more lenient 'rescue' set of significance thresholds for genes that are in the same operons as differentially expressed genes. I would favor the former approach, performing virtually all of their analysis at the level of transcriptional units rather than individual genes, as much of their analysis in any case relies upon proper assignment of genes to promoters, and this way they could focus on the most important signals rather than get lots sometimes in the weeds of looking at every single gene when really what they seem to be looking at in this paper is a property OF THE PROMOTERS, not the genes. (of course there are phenomena, such as rho dependent termination specifically titrating expression of late genes in operons, but I think on the balance the operon-level analysis might provide more insights and a cleaner analysis and discussion).

We agree with the reviewer that the peculiar nature of transcription in bacteria has to be taken into account in order to properly quantify the influence of cis variants in gene expression changes. We therefore added the exact analysis the reviewer suggested; that is, we ran associations between the variants in cis to the first gene of each operon and a phenotype that considered the fold-change of all genes in the operon, via a weighted average (see Methods for more details). As reported in the results section (L223), we found a similar trend as with the original analysis: we found the highest proportion of associations when encoding cis variants using k-mers (42% for E. coli and 45% for P. aeruginosa). More importantly, we found a high degree of overlap between this new “operon-level” association analysis and the original one (only including the first gene in each operon). We found a range of 90%-94% of associations overlapping for E. coli and between 75% and 91% for P. aeruginosa, depending on the variant type. We note that operon definitions are less precise for P. aeruginosa, which might explain the higher variability in the level of overlap. We have added the results of this analysis in the results section.

This also leads to a more general point, however, which I think is potentially more deeply problematic. At the end of the day, all of the analysis being done here centers on the cis regulatory logic upstream of each individual open reading frame, even though in many cases (i.e., genes after the first one in multi-gene operons), this is not where the relevant promoter is. This problem, in turn, raises potentially misattributions of causality running in both directions, where the causal impact on a bona fide promoter mutation on many genes in an operon may only be associated with the first gene, or on the other side, where a mutation that co-occurs with, but is causally independent from, an actual promoter mutation may be flagged as the one driving an expression change. This becomes an especially serious issue in cases like ulaE, for genes that are not the first gene in an operon (at least according to standard annotations, the UlaE transcript should be part of a polycistronic mRNA beginning from the ulaA promoter, and the role played by cis-regulatory logic immediately upstream of ulaE is uncertain and certainly merits deeper consideration. I suspect that many other similar cases likewise lurk in the dataset used here (perhaps even moreso for the Pseudomonas data, where the operon definitions are likely less robust). Of course there are many possible explanations, such as a separate ulaE promoter only in some strains, but this should perhaps be carefully stated and explored, and seems likely to be the exception rather than the rule.

While we again agree with the reviewer that some of our associations might not result in a direct causal link because the focal variant may not belong to an actual promoter element, we also want to point out how the ability to identify the composition of transcriptional units in bacteria is far from a solved problem (see references at the bottom of this comment, two in general terms, and one characterizing a specific example), even for a well-studied species such as E. coli. Therefore, even if carrying out associations at the operon level (e.g. by focusing exclusively on variants in cis for the first gene in the operon) might be theoretically correct, a number of the associations we find further down the putative operons might be the result of a true biological signal.

-

Conway, T., Creecy, J. P., Maddox, S. M., Grissom, J. E., Conkle, T. L., Shadid, T. M., Teramoto, J., San Miguel, P., Shimada, T., Ishihama, A., Mori, H., & Wanner, B. L. (2014). Unprecedented High-Resolution View of Bacterial Operon Architecture Revealed by RNA Sequencing. mBio, 5(4), 10.1128/mbio.01442-14. https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.01442-14

-

Sáenz-Lahoya, S., Bitarte, N., García, B., Burgui, S., Vergara-Irigaray, M., Valle, J., Solano, C., Toledo-Arana, A., & Lasa, I. (2019). Noncontiguous operon is a genetic organization for coordinating bacterial gene expression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(5), 1733–1738. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1812746116

-

Zehentner, B., Scherer, S., & Neuhaus, K. (2023). Non-canonical transcriptional start sites in E. coli O157:H7 EDL933 are regulated and appear in surprisingly high numbers. BMC Microbiology, 23(1), 243. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-023-02988-6

Another issue with the current definition of regulatory regions, which should perhaps also be accounted for, is that it is likely that for many operons, the 'regulatory regions' of one gene might overlap the ORF of the previous gene, and in some cases actual coding mutations in an upstream gene may contaminate the set of potential regulatory mutations identified in this dataset.

We agree that defining regulatory regions might be challenging, and that those regions might overlap with coding regions, either for the focal gene or the one immediately upstream. For these reasons we have defined a wide region to identify putative regulatory variants (-200 to +30 bp around the start codon of the focal gene). We believe this relatively wide region allows us to capture the most cis genetic variation.

Taken together, I feel that all of the above concerns need to be addressed in some way. At the absolute barest minimum, the authors need to acknowledge the weaknesses that I have pointed out in the definition of cis-regulatory logic at a gene level. I think it would be far BETTER if they performed a re-analysis at the level of transcriptional units, which I think might substantially strengthen the work as a whole, but I recognize that this would also constitute a substantial amount of additional effort.

As indicated above, we have added a section in the results section to report on the analysis carried out at the level of operons as individual units, with more details provided in the methods section. We believe these results, which largely overlap with the original analysis, are a good way to recognize the limitation of our approach and to acknowledge the importance of gaining a better knowledge on the number and composition of transcriptional units in bacteria, for which, as the reference above indicates, we still have an incomplete understanding.

Having reached the end of the paper, and considering the evidence and arguments of the authors in their totality, I find myself wondering how much local x background interactions - that is, the effects of cis regulatory mutations (like those being considered here, with or without the modified definitions that I proposed above) IN THE CONTEXT OF A PARTICULAR STRAIN BACKGROUND, might matter more than the effects of the cis regulatory mutations per se. This is a particularly tricky problem to address because it would require a moderate number of targeted experiments with a moderate number of promoters in a moderate number of strains (which of course makes it maximally annoying since one can't simply scale up hugely on either axis individually and really expect to tease things out). I think that trying to address this question experimentally is FAR beyond the scope of the current paper, but I think perhaps the authors could at least begin to address it by acknowledging it as a challenge in their discussion section, and possibly even identify candidate promoters that might show the largest divergence of activities across strains when there IS no detectable cis regulatory mutation (which might be indicative of local x background interactions), or those with the largest divergences of effect for a given mutation across strains. A differential expression model incorporating shrinkage is essential in such analysis to avoid putting too much weight on low expression genes with a lot of Poisson noise.

We again thank the reviewer for their thoughtful comments on the limitations of correlative studies in general, and microbial GWAS in particular. In regards to microbial GWAS we feel we may have failed to properly explain how the implementation we have used allows to, at least partially, correct for population structure effects. That is, the linear mixed model we have used relies on population structure to remove the part of the association signal that is due to the genetic background and thus focus the analysis on the specific loci. Obviously examples in which strong epistatic interactions are present would not be accounted for, but those would be extremely challenging to measure or predict at scale, as the reviewer rightfully suggests. We have added a brief recap of the ability of microbial GWAS to account for population structure in the results section (“A large fraction of gene expression changes can be attributed to genetic variations in cis regulatory regions”, e.g. L195).

I also have some more minor concerns and suggestions, which I outline below:

It seems that the differential expression analysis treats the lab reference strains as the 'centerpoint' against which everything else is compared, and yet I wonder if this is the best approach... it might be interesting to see how the results differ if the authors instead take a more 'average' strain (either chosen based on genetics or transcriptomics) as a reference and compared everything else to that.

While we don’t necessarily disagree with the reviewer that a “wild” strain would be better to compare against, we think that our choice to go for the reference isolates is still justified on two grounds. First, while it is true that comparing against a reference introduces biases in the analysis, this concern would not be removed had we chosen another strain as reference; which strain would then be best as a reference to compare against? We think that the second point provides an answer to this question; the “traditional” reference isolates have a rich ecosystem of annotations, experimental data, and computational predictions. These can in turn be used for validation and hypothesis generation, which we have done extensively in the manuscript. Had we chosen a different reference isolate we would have had to still map associations to the traditional reference, resulting in a probable reduction in precision. An example that will likely resonate with this reviewer is that we have used experimentally-validated and high quality computational operon predictions to look into likely associations between cis-variants and “operon DEGs”. This analysis would have likely been of worse quality had we used another strain as reference, for which operon definitions would have had to come from lower-quality predictions or be “lifted” from the traditional reference.

Line 104 - the statement about the differentially expressed genes being "part of operons with diverse biological functions" seems unclear - it is not apparent whether the authors are referring to diversity of function within each operon, or between the different operons, and in any case one should consider whether the observation reflects any useful information or is just an apparently random collection of operons.

We agree that this formulation could create confusion and we have elected to remove the expression “with diverse biological functions”, given that we discuss those functions immediately after that sentence.

Line 292 - I find the argument here somewhat unconvincing, for two reasons. First, the fact that only half of the observed changes went in the same direction as the GWAS results would indicate, which is trivially a result that would be expected by random chance, does not lend much confidence to the overall premise of the study that there are meaningful cis regulatory changes being detected (in fact, it seems to argue that the background in which a variant occurs may matter a great deal, at least as much as the cis regulatory logic itself). Second, in order to even assess whether the GWAS is useful to "find the genetic determinants of gene expression changes" as the authors indicate, it would be necessary to compare to a reasonable, non-straw-man, null approach simply identifying common sequence variants that are predicted to cause major changes in sigma 70 binding at known promoters; such a test would be especially important given the lack of directional accuracy observed here. Along these same lines, it is perhaps worth noting, in the discussion beginning on line 329, that the comparison is perhaps biased in favor of the GWAS study, since the validation targets here were prioritized based on (presumably strong) GWAS data.

We thank the reviewer for prompting us into reasoning about the results of the in-vitro validation experiments. We agree that the agreement between the measured gene expression changes agree only partly with those measured with the reporter system, and that this discrepancy could likely be attributed to regulatory elements that are not in cis, and thus that were not present in the in-vitro reporter system. We have noted this possibility in the discussion. Additionally, we have amended the results section to note that even though the prediction in the direction of gene expression change was not as accurate as it could be expected, the prediction of whether a change would be present (thus ignoring directionality) was much higher.

I don't find the Venn diagrams in Fig 7C-D useful or clear given the large number of zero-overlap regions, and would strongly advocate that the authors find another way to show these data.

While we are aware that alternative ways to show overlap between sets, such as upset plots, we don’t actually find them that much easier to parse. We actually think that the simple and direct Venn diagrams we have drawn convey the clear message that overlaps only exist between certain drug classes in E. coli, and virtually none for P. aeruginosa. We have added a comment on the lack of overlap between all drug classes and the differences between the two species in the results section (i.e. L436 and L465).

In the analysis of waa operon gene expression beginning on line 400, it is perhaps important to note that most of the waa operon doesn't do anything in laboratory K12 strains due to the lack of complete O-antigen... the same is not true, however, for many wild/clinical isolates. It would be interesting to see how those results compare, and also how the absolute TPMs (rather than just LFCs) of genes in this operon vary across the strains being investigated during TOB treatment.

We thank the reviewer for this helpful suggestion. We examined the absolute expression (TPMs) of waa operon genes under the baseline (A) and following exposure to Tobramycin (B). The representative TPMs per strain were obtained by averaging across biological replicates. We observed a constitutive expression of the genes in the reference strain (MG1655) and the other isolates containing the variant of interest (MC4100, BW25113). In contrast, strains lacking the variants of interest (IAI76 and IAI78), showed lower expression of these operon genes under both conditions. Strain IAI77, on the other hand, displayed increased expression of a subset of waa genes post Tobramycin exposure, indicating strain-specific variation in transcriptional response. While the reference isolate might not have the O-antigen, it certainly expresses the waa operon, both constitutively and under TOB exposure.

I don't think that the second conclusion on lines 479-480 is fully justified by the data, given both the disparity in available annotation information between the two species, AND the fact that only two species were considered.

While we feel that the “Discussion” section of a research paper allows for speculative statements, we have to concede that we have perhaps overreached here. We have amended this sentence to be more cautious and not mislead readers.

Line 118: "Double of DEGs"

Line 288 - presumably these are LOG fold changes

Fig 6b - legend contains typos

Line 661 - please report the read count (more relevant for RNA-seq analysis) rather than Gb

We thank the reviewer for pointing out the need to make these edits. We have implemented them all.

Source code - I appreciate that the authors provide their source code on github, but it is very poorly documented - both a license and some top-level documentation about which code goes with each major operation/conclusion/figure should be provided. Also, ipython notebooks are in general a poor way in my view to distribute code, due to their encouragement of nonlinear development practices; while they are fine for software development, actual complete python programs along with accompanying source data would be preferrable.

We agree with the reviewer that a software license and some documentation about what each notebook is about is warranted, and we have added them both. While we agree that for “consumer-grade” software jupyter notebooks are not the most ergonomic format, we believe that as a documentation of how one-time analyses were carried out they are actually one of the best formats we could think of. They in fact allow for code and outputs to be presented alongside each other, which greatly helped us to iterate on our research and to ensure that what was presented in the manuscript matched the analyses we reported in the code. This is of course up for debate and ultimately specific to someone’s taste, and so we will keep the reviewer’s critique in mind for our next manuscript. And, if we ever decide to package the analyses presented in the manuscript as a “consumer-grade” application for others to use, we would follow higher standards of documentation and design.

Reviewer #3 (Evidence, reproducibility and clarity (Required)):

In this manuscript, Damaris et al. collected genome sequences and transcriptomes from isolates from two bacterial species. Data for E. coli were produced for this paper, while data for P. aeruginosa had been measured earlier. The authors integrated these data to detect genes with differential expression (DE) among isolates as well as cis-expression quantitative trait loci (cis-eQTLs). The authors used sample sizes that were adequate for an initial exploration of gene regulatory variation (n=117 for E. coli and n=413 for P. aeruginosa) and were able to discover cis eQTLs at about 39% of genes. In a creative addition, the authors compared their results to transcription rates predicted from a biophysical promoter model as well as to annotated transcription factor binding sites. They also attempted to validate some of their associations experimentally using GFP-reporter assays. Finally, the paper presents a mapping of antibiotic resistance traits. Many of the detected associations for this important trait group were in non-coding genome regions, suggesting a role of regulatory variation in antibiotic resistance.

A major strength of the paper is that it covers an impressive range of distinct analyses, some of which in two different species. Weaknesses include the fact that this breadth comes at the expense of depth and detail. Some sections are underdeveloped, not fully explained and/or thought-through enough. Important methodological details are missing, as detailed below.

We thank the reviewer for highlighting the strengths of our study. We hope that our replies to their comments and the other two reviewers will address some of the limitations.

Major comments:

-

An interesting aspect of the paper is that genetic variation is represented in different ways (SNPs & indels, IRG presence/absence, and k-mers). However, it is not entirely clear how these three different encodings relate to each other. Specifically, more information should be given on these two points:

-

it is not clear how "presence/absence of intergenic regions" are different from larger indels.

In order to better guide readers through the different kinds of genetic variants we considered, we have added a brief explanation about what “promoter switches” are in the introduction (“meaning that the entire promoter region may differ between isolates due to recombination events”, L56). We believe this clarifies how they are very different in character from a large deletion. We have kept the reference to the original study (10.1073/pnas.1413272111) describing how widespread these switches are in E. coli as a way for readers to discover more about them.

- I recommend providing more narration on how the k-mers compare to the more traditional genetic variants (SNPs and indels). It seems like the k-mers include the SNPs and indels somehow? More explanation would be good here, as k-mer based mapping is not usually done in other species and is not standard practice in the field. Likewise, how is multiple testing handled for association mapping with k-mers, since presumably each gene region harbors a large number of k-mers, potentially hugely increasing the multiple testing burden?

We indeed agree with the reviewer in thinking that representing genetic variants as k-mers would encompass short variants (SNP/InDels) as well as larger variants and promoters presence/absence patterns. We believe that this assumption is validated by the fact that we identify the highest proportion of DEGs with a significant association when using this representation of variants (Figure 2A, 39% for both species). We have added a reference to a recent review on the advantages of k-mer methods for population genetics (10.1093/molbev/msaf047) in the introduction. Regarding the issue of multiple testing correction, we have employed a commonly recognized approach that, unlike a crude Bonferroni correction using the number of tested variants, allows for a realistic correction of association p-values. We used the number of unique presence/absence patterns, which can be shared between multiple genetic variants, and applied a Bonferroni correction using this number rather than the number of variants tested. We have expanded the corresponding section in the methods (e.g. L697) to better explain this point for readers not familiar with this approach.

- What was the distribution of association effect sizes for the three types of variants? Did IRGs have larger effects than SNPs as may be expected if they are indeed larger events that involve more DNA differences? What were their relative allele frequencies?

We appreciate the suggestion made by the reviewer to look into the distribution of effect sizes divided by variant type. We have now evaluated the distribution of the effect sizes and allele frequencies for the genetic markers (SNPs/InDels, IGRs, and k-mers) for both species (Supplementary Figure 2). In E. coli, IGR variants showed somewhat larger median effect sizes (|β| = 4.5) than SNPs (|β| = 3.8), whereas k-mers displayed the widest distribution (median |β| = 5.2). In P. aeruginosa, the trend differed with IGRs exhibiting smaller effects (median |β| = 3.2), compared to SNPs/InDels (median |β| =5.1) and k-mers (median |β| = 6.2). With respect to allele frequencies, SNPs/InDels generally occured at lower frequencies (median AF = 0.34 for E.coli, median AF = 0.33 for P. aeruginosa), whereas IGRs (median AF = 0.65 for E. coli and 0.75 for P. aeruginosa) and k-mers (median AF = 0.71 for E. coli and 0.65 for P. aeruginosa) were more often at the intermediate to higher frequencies respectively. We have added a visualization for the distribution of effect sizes (Supplementary Figure 2).

- The GFP-based experiments attempting to validate the promoter effects for 18 genes are laudable, and the fact that 16 of them showed differences is nice. However, the fact that half of the validation attempts yielded effects in the opposite direction of what was expected is quite alarming. I am not sure this really "further validates" the GWAS in the way the authors state in line 292 - in fact, quite the opposite in that the validations appear random with regards to what was predicted from the computational analyses. How do the authors interpret this result? Given the higher concordance between GWAS, promoter prediction, and DE, are the GFP assays just not relevant for what is going on in the genome? If not, what are these assays missing? Overall, more interpretation of this result would be helpful.

We thanks the reviewer for their comment, which is similar in nature to that raised by reviewer #2 above. As noted in our reply above we have amended the results and discussion to indicate that although the direction of gene expression change was not highly accurate, focusing on the magnitude (or rather whether there would be a change in gene expression, regardless of the direction), resulted in a higher accuracy. We postulate that the cases in which the direction of the change was not correctly identified could be due to the influence of other genetic elements in trans with the gene of interest.

- On the same note, it would be really interesting to expand the GFP experiments to promoters that did not show association in the GWAS. Based on Figure 6, effects of promoter differences on GFP reporters seem to be very common (all but three were significant). Is this a higher rate than for the average promoter with sequence variation but without detected association? A handful of extra reporter experiments might address this. My larger question here is: what is the null expectation for how much functional promoter variation there is?

We thank the reviewer for this comment. We agree that estimating the null expectation for the functional promoter would require testing promoter alleles with sequence variation that are not associated in the GWAS. Such experiments, which would directly address if the observed effects in our study exceeds background, would have required us to prepare multiple constructs, which was unfortunately not possible for us due to staff constraints. We therefore elected to clarify the scope of our GFP reporter assays instead. These experiments were designed as a paired comparison of the wild-type and the GWAS-associated variant alleles of the same promoter in an identical reporter background, with the aim of testing allele-specific functional effects for GWAS hits (Supplementary Figure 6). We also included a comparison in GFP fluorescence between the promoterless vector (pOT2) and promoter-containing constructs; we observed higher GFP signals in all but four (yfgJ, fimI, agaI, and yfdQ) variant-containing promoter constructs, which indicates that for most of the construct we cloned active promoter elements. We have revised the manuscript text accordingly to reflect this clarification and included the control in the supplementary information as Supplementary Figure 6.

- Were the fold-changes in the GFP experiments statistically significant? Based on Figure 6 it certainly looks like they are, but this should be spelled out, along with the test used.

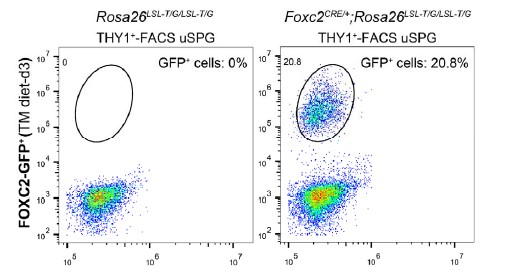

We thank the reviewer for pointing this out. We have reviewed Figure 6 to indicate significant differences between the test and control reporter constructs. We used the paired student’s t-test to match the matched plate/time point measurements. We also corrected for multiple testing using the Benhamini-Hochberg correction. As seen in the updated Figure 6A, 16 out of the 18 reporter constructs displayed significant differences (adjusted p-value

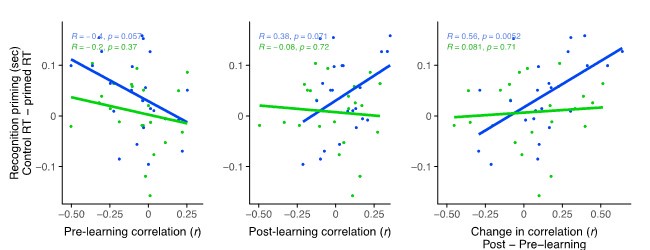

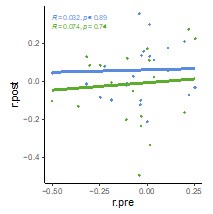

- What was the overall correlation between GWAS-based fold changes and those from the GFP-based validation? What does Figure 6A look like as a scatter plot comparing these two sets of values?

We thank the reviewer for this helpful suggestion, which allows us to more closely look into the results of our in-vitro validation. We performed a direct comparison of RNAseq fold changes from the GWAS (x-axis) with the GFP reporter measurements (y-axis) as depicted in the figure above. The overall correlation between the two was weak (Pearson r = 0.17), reflecting the lack of thorough agreement between the associations and the reporter construct. We however note that the two metrics are not directly comparable in our opinion, since on the x-axis we are measuring changes in gene expression and on the y-axis changes in fluorescence expression, which is downstream from it. As mentioned above and in reply to a comment from reviewer 2, the agreement between measured gene expression and all other in-silico and in-vitro techniques increases when ignoring the direction of the change. Overall, we believe that these results partly validate our associations and predictions, while indicating that other factors in trans with the regulatory region contribute to changes in gene expression, which is to be expected. The scatter plot has been included as a new supplementary figure (Supplementary Figure 7).

- Was the SNP analyzed in the last Results section significant in the gene expression GWAS? Did the DE results reported in this final section correspond to that GWAS in some way?

The T>C SNP upstream of waaQ did not show significant association with gene expression in our cis GWAS analysis. Instead, this variant was associated with resistance to tobramycin when referencing data from Danesh et al, and we observed the variant in our strain collection. We subsequently investigated whether this variant also influenced expression of the waa operon under sub-inhibitory tobramycin exposure. The differential expression results shown in the final section therefore represent a functional follow-up experiment, and not a direct replication of the GWAS presented in the first part of the manuscript.

- Line 470: "Consistent with the differences in the genetic structure of the two species" It is not clear what differences in genetic structure this refers to. Population structure? Genome architecture? Differences in the biology of regulatory regions?

The awkwardness of that sentence is perhaps the consequence of our assumption that readers would be aware of the differences in population genetics differences between the two species. We however have realized that not much literature is available (if at all!) about these differences, which we have observed during the course of this and other studies we have carried out. As a result, we agree that we cannot assume that the reader is similarly familiar with these differences, and have changed that sentence (i.e. L548) to more directly address the differences between the two species, which will presumably result in a diverse population structure. We thank the reviewer for letting us be aware of a gap in the literature concerning the comparison of pangenome structures across relevant species.

- Line 480: the reference to "adaption" is not warranted, as the paper contains no analyses of evolutionary patterns or processes. Genetic variation is not the same as adaptation.

We have amended this sentence to be more adherent to what we can conclude from our analyses.

- There is insufficient information on how the E. coli RNA-seq data was generated. How was RNA extracted? Which QC was done on the RNA; what was its quality? Which library kits were used? Which sequencing technology? How many reads? What QC was done on the RNA-seq data? For this section, the Methods are seriously deficient in their current form and need to be greatly expanded.

We thank the reviewer for highlighting the need for clearer methodological detail. We have expanded this section (i.e. L608) to fully describe the generation and quality control of the E. coli RNA-seq data including RNA extraction and sequencing platform.

- How were the DEG p-values adjusted for multiple testing?

As indicated in the methods section (“Differential gene expression and functional enrichment analysis”), we have used DEseq2 for E. coli, and LPEseq for P. aeruginosa. Both methods use the statistical framework of the False Discovery Rate (FDR) to compute an adjusted p-value for each gene. We have added a brief mention of us following the standard practice indicated by both software packages in the methods.

- Were there replicates for the E. coli strains? The methods do not say, but there is a hint there might have been replicates given their absence was noted for the other species.

In the context of providing more information about the transcriptomics experiments for E. coli, we have also more clearly indicated that we have two biological replicates for the E. coli dataset.

- There needs to be more information on the "pattern-based method" that was used to correct the GWAS for multiple tests. How does this method work? What genome-wide threshold did it end up producing? Was there adjustment for the number of genes tested in addition to the number of variants? Was the correction done per variant class or across all variant classes?

In line with an earlier comment from this reviewer, we have expanded the section in the Methods (e.g. L689) that explains how this correction worked to include as many details as possible, in order to provide the readers with the full context under which our analyses were carried out.

- For a paper that, at its core, performs a cis-eQTL mapping, it is an oversight that there seems not to be a single reference to the rich literature in this space, comprising hundreds of papers, in other species ranging from humans, many other animals, to yeast and plants.

We thank both reviewer #1 and #3 for pointing out this lack of references to the extensive literature on the subject. We have added a number of references about the applications of eQTL studies, and specifically its application in microbial pangenomes, which we believe is more relevant to our study, in the introduction.

Minor comments:

- I wasn't able to understand the top panels in Figure 4. For ulaE, most strains have the solid colors, and the corresponding bottom panel shows mostly red points. But for waaQ, most strains have solid color in the top panel, but only a few strains in the bottom panel are red. So solid color in the top does not indicate a variant allele? And why are there so many solid alleles; are these all indels? Even if so, for kgtP, the same colors (i.e., nucleotides) seem to seamlessly continue into the bottom, pale part of the top panel. How are these strains different genotypically? Are these blocks of solid color counted as one indel or several SNPs, or somehow as k-mer differences? As the authors can see, these figures are really hard to understand and should be reworked. The same comment applies to Figure 5, where it seems that all (!) strains have the "variant"?

We thank the reviewer for pointing out some limitations with our visualizations, most importantly with the way we explained how to read those two figures. We have amended the captions to more explicitly explain what is shown. The solid colors in the “sequence pseudo-alignment” panels indicate the focal cis variant, which is indicated in red in the corresponding “predicted transcription rate” panels below. In the case of Figure 5, the solid color indicates instead the position of the TFBS in the reference.

- Figure 1A & B: It would be helpful to add the total number of analyzed genes somewhere so that the numbers denoted in the colored outer rings can be interpreted in comparison to the total.

We have added the total number of genes being considered for either species in the legend.

- Figure 1C & D: It would be better to spell out the COG names in the figure, as it is cumbersome for the reader to have to look up what the letters stand for in a supplementary table in a separate file.

While we do not disagree with the awkwardness of having to move to a supplementary table to identify the full name of a COG category, we also would like to point out that the very long names of each category would clutter the figure to a degree that would make it difficult to read. We had indeed attempted something similar to what the reviewer suggests in early drafts of this manuscript, leading to small and hard to read labels. We have therefore left the full names of each COG category in Supplementary Table 3.

- Line 107: "Similarly," does not fit here as the following example (with one differentially expressed gene in an operon) is conceptually different from the one before, where all genes in the operon were differentially expressed.

We agree and have amended the sentence accordingly.

- Figure 5 bottom panel: it is odd that on the left the swarm plots (i.e., the dots) are on the inside of the boxplots while on the right they are on the outside.

We have fixed the position of the dots so that they are centered with respect to the underlying boxplots.

- It is not clear to me how only one or a few genes in an operon can show differential mRNA abundance. Aren't all genes in an operon encoded by the same mRNA? If so, shouldn't this mRNA be up- or downregulated in the same manner for all genes it encodes? As I am not closely familiar with bacterial systems, it is well possible that I am missing some critical fact about bacterial gene expression here. If this is not an analysis artifact, the authors could briefly explain how this observation is possible.

We thanks the reviewer for their comment, which again echoes one of the main concerns from reviewer #2. As noted in our reply above, it has been established in multiple studies (see the three we have indicated above in our reply to reviewer #2) how bacteria encode for multiple “non-canonical” transcriptional units (i.e. operons), due to the presence of accessory terminators and promoters. This, together with other biological effects such as the presence of mRNA molecules of different lengths due to active transcription and degradation and technical noise induced by RNA isolation and sequencing can result in variability in the estimation of abundance for each gene.

-

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

eLife Assessment

This work provides an important resource identifying 72 proteins as novel candidates for plasma membrane and/or cell wall damage repair in budding yeast, and describes the temporal coordination of exocytosis and endocytosis during the repair process. The data are convincing; however, additional experimental validation will better support the claim that repair proteins shuttle between the bud tip and the damage site.

We thank the editors and reviewers for their positive assessment of our work and the constructive feedback to improve our manuscript. We agree with the assessment that additional validation of repair protein shuttling between the bud tip and the damage site is required to further support the model.

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

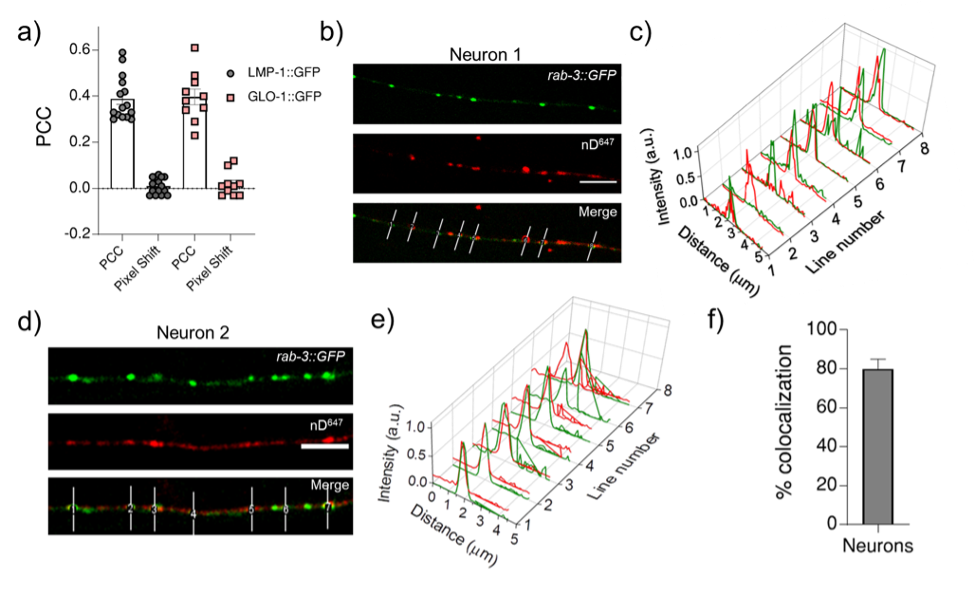

In this manuscript, Yamazaki et al. conducted multiple microscopy-based GFP localization screens, from which they identified proteins that are associated with PM/cell wall damage stress response. Specifically, the authors identified that budlocalized TMD-containing proteins and endocytotic proteins are associated with PM damage stress. The authors further demonstrated that polarized exocytosis and CME are temporally coupled in response to PM damage, and CME is required for polarized exocytosis and the targeting of TMD-containing proteins to the damage site. From these results, the authors proposed a model that CME delivers TMD-containing repair proteins between the bud tip and the damage site.

Strengths:

Overall, this is a well-written manuscript, and the experiments are well-conducted. The authors identified many repair proteins and revealed the temporal coordination of different categories of repair proteins. Furthermore, the authors demonstrated that CME is required for targeting of repair proteins to the damage site, as well as cellular survival in response to stress related to PM/cell wall damage. Although the roles of CME and bud-localized proteins in damage repair are not completely new to the field, this work does have conceptual advances by identifying novel repair proteins and proposing the intriguing model that the repairing cargoes are shuttled between the bud tip and the damaged site through coupled exocytosis and endocytosis.

Weaknesses:

While the results presented in this manuscript are convincing, they might not be sufficient to support some of the authors' claims. Especially in the last two result sessions, the authors claimed CME delivers TMD-containing repair proteins from the bud tip to the damage site. The model is no doubt highly possible based on the data, but caveats still exist. For example, the repair proteins might not be transported from one localization to another localization, but are degraded and resynthesized. Although the Gal-induced expression system can further support the model to some extent, I think more direct verification (such as FLIP or photo-convertible fluorescence tags to distinguish between pre-existing and newly synthesized proteins) would significantly improve the strength of evidence.

Major experiment suggestions:

(1) The authors may want to provide more direct evidence for "protein shuttling" and for excluding the possibility that proteins at the bud are degraded and synthesized de novo near the damage site. For example, if the authors could use FLIP to bleach budlocalized fluorescent proteins, and the damaged site does not show fluorescent proteins upon laser damage, this will strongly support the authors' model. Alternatively, the authors could use photo-convertible tags (e.g., Dendra) to differentiate between preexisting repair proteins and newly synthesized proteins.

We thank the reviewer for evaluating our work and giving us important feedback. We agree that the FLIP and photo-convertible experiments will further confirm our model. Here, due to time and resource constraints, we decided not to perform this experiment. Instead, we have discussed this limitation in 363-366. Our proposed model of repair protein shuttling should be further tested in our future work.

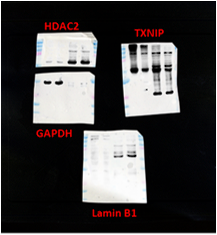

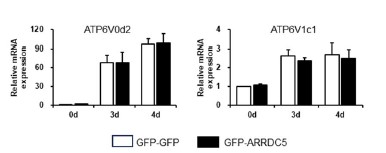

(2) In line with point 1, the authors used Gal-inducible expression, which supported their model. However, the author may need to show protein abundance in galactose, glucose, and upon PM damage. Western blot would be ideal to show the level of fulllength proteins, or whole-cell fluorescence quantification can also roughly indicate the protein abundance. Otherwise, we cannot assume that the tagged proteins are only expressed when they are growing in galactose-containing media.

Thank you very much for raising the concern and suggesting the important experiments.We agree that the Western blot experiment to confirm the mNG-Snc1 expression in each medium will further strengthen our conclusion. Along with point (1), further investigation of repair protein shuttling between the bud tip and the damage site and the mechanisms underlying it will be an important future direction. As described above, we have discussed this limitation in 363-366.

(3) Similarly, for Myo2 and Exo70 localization in CME mutants (Figure 4), it might be worth doing a western or whole-cell fluorescence quantification to exclude the caveat that CME deficiency might affect protein abundance or synthesis.

We thank the reviewer for suggesting the point. Following the reviewer’s suggestion, we quantified the whole-cell fluorescence of WT and CME mutants and verified that the effect of the CME deletion on the expression levels of Myo2-sfGFP and Exo70-mNG is minimal ( Figure S6). We added the description in lines 211-212.

(4) From the authors' model in Figure 7, it looks like the repair proteins contribute to bud growth. Does laser damage to the mother cell prevent bud growth due to the reduction of TMD-containing repair proteins at the bud? If the authors could provide evidence for that, it would further support the model.

Thank you very much for raising the important point. We speculate that the reduction of TMD-containing proteins at the bud by CME is one of the causes of cell growth arrest after PM damage (1). This is because TMD-containing repair proteins at the bud tip, including phospholipid flippases (Dnf1/Dnf2), Snc1, and Dfg5, are involved in polarized cell growth (2-4). This will be an important future direction as well.

(5) Is the PM repair cell-cycle-dependent? For example, would the recruitment of repair proteins to the damage site be impaired when the cells are under alpha-factor arrest?

Thank you for raising this interesting point. Indeed, the senior author Kono previously performed this experiment when she was in David Pellman’s lab. The preliminary results suggest that Pkc1 can be targeted to the damage site, without any impairment, under alpha-factor arrest. A more comprehensive analysis in the future will contribute to concluding the relation between PM repair and the cell cycle.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

This paper remarkably reveals the identification of plasma membrane repair proteins, revealing spatiotemporal cellular responses to plasma membrane damage. The study highlights a combination of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and lase for identifying and characterizing proteins involved in plasma membrane (PM) repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. From 80 PM, repair proteins that were identified, 72 of them were novel proteins. The use of both proteomic and microscopy approaches provided a spatiotemporal coordination of exocytosis and clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME) during repair. Interestingly, the authors were able to demonstrate that exocytosis dominates early and CME later, with CME also playing an essential role in trafficking transmembrane-domain (TMD)containing repair proteins between the bud tip and the damage site.

Weaknesses/limitations:

(1) Why are the authors saying that Pkc1 is the best characterized repair protein? What is the evidence?

We would like to thank the reviewer for taking his/her time to evaluate our work and for valuable suggestions. We described Pkc1 as “best characterized” because it was the first protein reported to accumulate at the laser damage site in budding yeast (5). However, as the reviewer suggested, we do not have enough evidence to describe Pkc1 as “best characterized”. We therefore used “one of the known repair proteins” to mention Pkc1 in the manuscript (lines 90-91).

(2) It is unclear why the authors decided on the C-terminal GFP-tagged library to continue with the laser damage assay, exclusively the C-terminal GFP-tagged library. Potentially, this could have missed N-terminal tag-dependent localizations and functions and may have excluded functionally important repair proteins

Thank you very much for the comments. We decided to use the C-terminal GFP-tagged library for the laser damage assay because we intended to evaluate the proteins of endogenous expression levels. The N-terminal sfGFP-tagged library is expressed by the NOP1 promoter, while the C-terminal GFP-tagged library is expressed by the endogenous promoters. We clarified these points in lines 114-118. We agree with the reviewer on that we may have missed some portion of repair proteins in the N-terminaldependent localization and functions by this approach. Therefore, in our manuscript, we discussed these limitations in lines 281-289.

(3) The use of SDS and laser damage may bias toward proteins responsive to these specific stresses, potentially missing proteins involved in other forms of plasma membrane injuries, such as mechanical, osmotic, etc.). SDS stress is known to indirectly induce oxidative stress and heat-shock responses.

Thank you very much for raising this point. We agree that the combination of SDS and laser may be biased to identify PM repair proteins. Therefore, in the manuscript, we discussed this point as a limitation of this work in lines 292-298.

(4) It is unclear what the scale bars of Figures 3, 5, and 6 are. These should be included in the figure legend.

We apologize for the missing scale bars. We added them to the legends of the figures in the manuscript.

(5) Figure 4 should be organized to compare WT vs. mutant, which would emphasize the magnitude of impairment.

Thank you for raising this point. Following the suggestion, we updated Figure 4. In the Figure 4, we compared WT vs mutant in the manuscript. We clarified it in the legends in the manuscript.

(6) It would be interesting to expand on possible mechanisms for CME-mediated sorting and retargeting of TMD proteins, including a speculative model.

Thank you very much for this important suggestion. We think it will be very important to characterize the mechanism of CME-mediated TMD protein trafficking between the bud tip and the damage site. In the manuscript, we discussed the possible mechanism for CME activation at the damage site in lines 328-333. We speculate that the activation of the CME may facilitate the retargeting of the TMD proteins from the damage site to the bud tip.

We do not have a model of how CMEs activate at the bud tip to sort and target the TMD proteins to the damage site. One possibility is that the cell cycle arrest after PM damage (1) may affect the localization of CME proteins because the cell cycle affects the localization of some of the CME proteins (6). We will work on the mechanism of repair protein sorting from the bud tip to the damage site in our future work.

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

Summary:

This work aims to understand how cells repair damage to the plasma membrane (PM). This is important, as failure to do so will result in cell lysis and death. Therefore, this is an important fundamental question with broad implications for all eukaryotic cells. Despite this importance, there are relatively few proteins known to contribute to this repair process. This study expands the number of experimentally validated PM from 8 to 80. Further, they use precise laser-induced damage of the PM/cell wall and use livecell imaging to track the recruitment of repair proteins to these damage sites. They focus on repair proteins that are involved in either exocytosis or clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME) to understand how these membrane remodeling processes contribute to PM repair. Through these experiments, they find that while exocytosis and CME both occur at the sites of PM damage, exocytosis predominates in the early stages of repairs, while CME predominates in the later stages of repairs. Lastly, they propose that CME is responsible for diverting repair proteins localized to the growing bud cell to the site of PM damage.

Strengths:

The manuscript is very well written, and the experiments presented flow logically. The use of laser-induced damage and live-cell imaging to validate the proteome-wide screen using SDS-induced damage strengthens the role of the identified candidates in PM/cell wall repair.

Weaknesses:

(1) Could the authors estimate the fraction of their candidates that are associated with cell wall repair versus plasma membrane repair? Understanding how many of these proteins may be associated with the repair of the cell wall or PM may be useful for thinking about how these results are relevant to systems that do or do not have a cell wall. Perhaps this is already in their GO analysis, but I don't see it mentioned in the manuscript.

We would like to thank the reviewer for taking his/her time to evaluate our work and valuable suggestions. We agree that this is important information to include. Although it may be difficult to completely distinguish the PM repair and cell wall repair proteins, we have identified at least six proteins involved in cell wall synthesis (Flc1, Dfg5, Smi1, Skg1, Tos7, and Chs3). We included this information in lines 142-146 in the manuscript.

(2) Do the authors identify actin cable-associated proteins or formin regulators associated with sites of PM damage? Prior work from the senior author (reference 26) shows that the formin Bnr1 relocalizes to sites of PM damage, so it would be interesting if Bnr1 and its regulators (e.g., Bud14, Smy1, etc) are recruited to these sites as well. These may play a role in directing PM repair proteins (see more below).

Thank you for the suggestion. We identified several Bnr1-interacting proteins, including Bud6, Bil1, and Smy1 (Table S2), although Bnr1 itself was not identified in our screening. This could be attributed to the fact that (1) C-terminal GFP fusion impaired the function of Bnr1, and (2) a single GFP fusion is not sufficient to visualize the weak signal at the damage site. Indeed, in reference 26, 3GFP-Bnr1 (N-terminal 3xGFP fusion) was used.

(3) Do the authors suspect that actin cables play a role in the relocalization of material from the bud tip to PM damage sites? They mention that TMD proteins are secretory vesicle cargo (lines 134-143) and that Myo2 localizes to damage sites. Together, this suggests a possible role for cable-based transport of repair proteins. While this may be the focus of future work, some additional discussion of the role of cables would strengthen their proposed mechanism (steps 3 and 4 in Figure 7).

Thank you very much for the suggestion. We agree that actin cables may play a role in the targeting of vesicles and repair proteins to the damage site. Following the reviewer’s suggestion, we discussed the roles of Bnr1 and actin cables for repair protein trafficking in lines 309-313 in the manuscript.

(4) Lines 248-249: I find the rationale for using an inducible Gal promoter here unclear. Some clarification is needed.

Thank you for raising this point. We clarified this as possible as we could in lines 249255 in the manuscript.

Recommendations for the authors:

Reviewer #1 (Recommendations for the authors):

(1) The N-terminal GFP collection screen is interesting but seems irrelevant to the rest of the results. The authors discussed that in the discussion part, but it might be worth showing how many hits from the laser damage screen (in Figure 2) overlap with the Nterminal GFP screen hits.

Thank you for the suggestion. We found that 48 out of 80 repair proteins are hits in the N-terminal GFP library (Table S1 and S2). This result suggested that the N-terminal library is also a useful resource for identifying repair proteins. In the manuscript, we discussed it in lines 288-289.

(2) SDS treatment seems a harsh stressor. As the authors mentioned, the overlapped hits from the N- and C-terminal GFP screen might be more general stress factors. Thus, I think Line 84 (the subtitle) might be overclaiming, and the authors might need to tone down the sentence.

Thank you for the suggestion. Following the reviewer’s suggestion, we changed the sentence to “Proteome-scale identification of SDS-responsive proteins” in the manuscript. We believe that the new sentence describes our findings more precisely.

(3) Line 103-106, it does not seem obvious to me that the protein puncta in the cytoplasm are due to endocytosis. The authors might need to provide more experimental evidence for the conclusion, or at least provide more reasoning/references on that aspect (e.g.,several specific protein hits belonging to that group have been shown to be endocytosed).

Thank you very much for raising this point. We agree with the reviewer and deleted the description that these puncta are due to endocytosis in the manuscript.

(4) For Figure 1D and S1C, the authors annotated some of the localization changes clearly, but some are confusing to me. For example," from bud tip/neck" to where? And from where to "Puncta/foci"? A clearer annotation might help the readers to understand the categorization.

Thank you very much for the suggestion. These annotations were defined because it is difficult to conclusively describe the protein localization after SDS treatment. To convincingly identify the destination of the GFP fusion proteins, the dual color imaging of proteins with organelle markers or deep learning-based localization estimation is required. We feel that this might be out of the scope of this work. Therefore, as criteria, we used the localization of protein localization in normal/non-stressed conditions reported in (7) and the Saccharomyces Genome Database (SGD). We clarified this annotation definition in the manuscript (lines 413-436).

(5) For localization in Figure 2C, as I understand, does it refer to6 the "before damage/normal" localization? If so, I think it would be helpful to state that these localizations are based on the untreated/normal conditions in the text.

Yes, it refers to the “before damage/normal localization”. Following the reviewer’s suggestion, we stated that these localizations are based on these conditions in the manuscript (line 130).

(6) The authors mentioned "four classes" in Line 120, but did not mention the "PM to cytoplasm" class in the text. It would be helpful to discuss/speculate why these transporters might contribute to PM damage repair.