Comment by onewheeljoe:

For example, we might simply ask that each participant refrain from using hashtags as a final thought because that is a form of sarcasm or punchline that can be misconstrued or shut down honest debate or agreeable disagreement.

We could ask respondents to reply to any comment that they read twice because of tone to use "ouch" as a tag or a textual response. The offending respondent could respond with "oops" in order to preserve good will in an exchange of ideas.

Finally, the first part of a flash mob might occur here, in the page notes, where norms could be quickly negotiated and agreed upon with a form of protocol.

Welcome to the

Welcome to the

I ask my students to respond to reading using Says Means Matters charts. I like them as a flexible tool that provides an opportunity to speak to the text's relevance to their lives. Here's an example of how I model the practice.

I ask my students to respond to reading using Says Means Matters charts. I like them as a flexible tool that provides an opportunity to speak to the text's relevance to their lives. Here's an example of how I model the practice. Our thanks to partner author Sophia Sarigianides for contributing to the 2019-20 Marginal Syllabus! Dr. Sarigianides' bio is included at the end of this article.

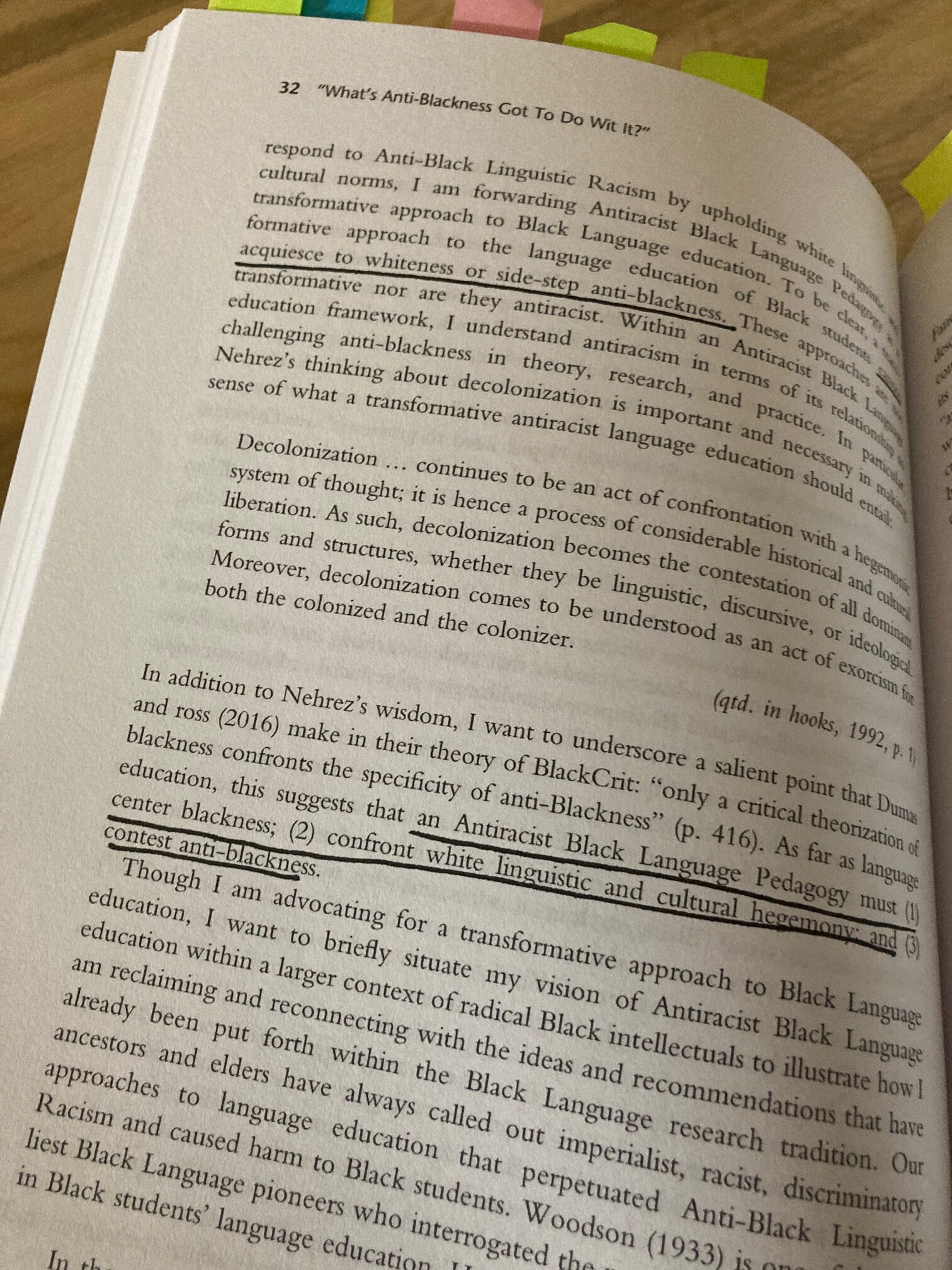

Our thanks to partner author Sophia Sarigianides for contributing to the 2019-20 Marginal Syllabus! Dr. Sarigianides' bio is included at the end of this article. Annotation is a form of conversation.

Annotation is a form of conversation. If you are joining a Marginal Syllabus conversation for the first time, or if you are using Hypothesis to annotate for the first time, here are a few useful notes and resources:

If you are joining a Marginal Syllabus conversation for the first time, or if you are using Hypothesis to annotate for the first time, here are a few useful notes and resources: Welcome to the 2019-20 Marginal Syllabus and our May conversation! This is the seventh article we will read and publicly annotate as part of "

Welcome to the 2019-20 Marginal Syllabus and our May conversation! This is the seventh article we will read and publicly annotate as part of " Our thanks to partner authors Ashley Boyd and Jacinda Miller for contributing to the 2019-20 Marginal Syllabus!

Our thanks to partner authors Ashley Boyd and Jacinda Miller for contributing to the 2019-20 Marginal Syllabus! Welcome to the 2019-20 Marginal Syllabus and our April conversation! This is the sixth article we will read and publicly annotate as part of "

Welcome to the 2019-20 Marginal Syllabus and our April conversation! This is the sixth article we will read and publicly annotate as part of " Our thanks to partner author Dr. Sakeena Everett for contributing to the 2019-20 Marginal Syllabus! This is the second time that Dr. Everett has joined the Marginal Syllabus as a partner author, having previously done so during the 2017-18 Writing Our Civic Futures syllabus - please also read her co-authored article, and the associated annotation conversation, about

Our thanks to partner author Dr. Sakeena Everett for contributing to the 2019-20 Marginal Syllabus! This is the second time that Dr. Everett has joined the Marginal Syllabus as a partner author, having previously done so during the 2017-18 Writing Our Civic Futures syllabus - please also read her co-authored article, and the associated annotation conversation, about  Welcome to the 2019-20 Marginal Syllabus and our March conversation! This is the fifth article we will read and publicly annotate as part of "

Welcome to the 2019-20 Marginal Syllabus and our March conversation! This is the fifth article we will read and publicly annotate as part of " Welcome to the 2019-20 Marginal Syllabus and our February conversation! This is the fourth article we will read and publicly annotate as part of "

Welcome to the 2019-20 Marginal Syllabus and our February conversation! This is the fourth article we will read and publicly annotate as part of "

Our thanks to partner author Alex Corbitt for contributing to the 2019-20 Marginal Syllabus! To learn more about Alex visit:

Our thanks to partner author Alex Corbitt for contributing to the 2019-20 Marginal Syllabus! To learn more about Alex visit:  Welcome to the 2019-20 Marginal Syllabus and our January conversation! This is the third article we will read and publicly annotate as part of "

Welcome to the 2019-20 Marginal Syllabus and our January conversation! This is the third article we will read and publicly annotate as part of "

Welcome to the 2019-20 Marginal Syllabus and our December conversation! This is the second article we will read and publicly annotate as part of "

Welcome to the 2019-20 Marginal Syllabus and our December conversation! This is the second article we will read and publicly annotate as part of "