- Mar 2023

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):<br /> <br /> Gonzalez and colleagues investigate dopamine signals in response to visual stimuli. This work builds on the longstanding notion that dopamine neurons respond to unexpected sensory stimuli, including visual cues. Using fiber photometry measurements of a fluorescent dopamine sensor, they find that in the lateral ventral striatum, dopamine signals reliably report salient transitions in illuminance. Dopamine signals scale with light intensity and the speed of illuminance changes. They further find that the frequency of illuminance transitions, rather than the number, dictates the extent that dopamine signals habituate. In a number of studies, they characterize dopamine signals to light of different wavelengths, durations, and intensities. These results shed new "light" on the role of dopamine in signaling salience, independent of reward or threat learning. This work is elegantly done and compelling. While the results are potentially specific to this region of the striatum, rather than a broad dopaminergic profile of visual stimulus encoding, this work offers valuable insight into dopamine function, as well as a practical guide and considerations for the implementation of visual stimuli in behavioral tasks that assay dopamine systems.

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

This manuscript by Sano et al., presents cryo-EM structure of endothelin-1-bound endothelin B receptor (ETbR) in complex with heterotrimeric G-proteins. The structural snapshot provides important information about agonist-induced receptor activation and transducer-coupling. This manuscript also designs and present a successful case example for a variation of previously used NanoBiT-fusion-based strategy to stabilize GPCR-G-protein complexes. This strategy may be broadly applicable to other GPCR-G-protein complexes as well, and therefore, also provides an important methodological advance. Overall, the experimental design and interpretation of the structure are excellent, and the manuscript present an easy-to-follow coherent story. Considering the importance of ETbR signaling in multiple physiological and disease conditions, this structural snapshot, taken together with earlier structural studies by the same laboratory, advances the ETbR biology significantly with potential for novel ligand discovery. This manuscript is also available as a preprint in bioRxiv as well as another manuscript from Xu and Jiang group. Considering the structural information presented in these manuscripts, I would strongly suggest that even if the other manuscript is published somewhere before this one, it should not be viewed as a compromise on novelty, and rather considered as complementary information from independent studies that further strengthen the impact.

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

The study focuses on a compelling question focusing on a largely indispensable mechanism, ribonucleotide reduction. The authors generate a unique specific bacterial strain where the ribonucleotide reducatase operon, entirely, is deleted. They grow the mutant strain in environments that have various amounts of the necessary deoxyribonucleoside levels, further, they perform evolution experiments to see whether and how the evolved lines would be able to adapt to the limited deoxyribonucleosides. Finally, researchers identify key mutations and generate key isogenic genetic constructs where target mutants are deleted. A summary postulation based on the evolutionary trajectory of ribonucleotide reduction by bacteria is presented. Overall, the study is well presented, well-justified, and builds on fairly classic genetic and evolution experiments. The select question and hypotheses and the overall framing of the story are fairly novel for the respective communities. The results should be interesting to evolutionary biology researchers, especially those interested in RNA>DNA directional evolution, as well as molecular microbiologists interested in the ribonucleotide reception dependence and selection by the environment. A discussion on the limitations of the laboratory study for the broader understanding of the host dependence during endosymbiosis and parasitism would be a good addition given the emphasis on this phenomenon as a part of the broader impacts of the study.

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

Shen et al. attempt to reconcile two distinct features of neural responses in frontoparietal areas during perceptual and value-guided decision-making into a single biologically realistic circuit model. First, previous work has demonstrated that value coding in the parietal cortex is relative (dependent on the value of all available choice options) and that this feature can be explained by divisive normalization, implemented using adaptive gain control in a recurrently connected circuit model (Louie et al, 2011). Second, a wealth of previous studies on perceptual decision-making (Gold & Shadlen 2007) have provided strong evidence that competitive winner-take-all dynamics implemented through recurrent dynamics characterized by mutual inhibition (Wang 2008) can account for categorical choice coding. The authors propose a circuit model whose key feature is the flexible gating of 'disinhibition', which captures both types of computation - divisive normalization and winner-take-all competition. The model is qualitatively able to explain the 'early' transients in parietal neural responses, which show signatures of divisive normalization indicating a relative value code, persistent activity during delay periods, and 'late' accumulation-to-bound type categorical responses prior to the report of choice/action onset.

The attempt to integrate these two sets of findings by a unified circuit model is certainly interesting and would be useful to those who seek a tighter link between biologically realistic recurrent neural network models and neural recordings. I also appreciate the effort undertaken by the authors in using analytical tools to gain an understanding of the underlying dynamical mechanism of the proposed model. However, I have two major concerns. First, the manuscript in its current form lacks sufficient clarity, specifically in how some of the key parameters of the model are supposed to be interpreted (see point 1 below). Second, the authors overlook important previous work that is closely related to the ideas that are being presented in this paper (see point 2 below).

1) The behavior of the proposed model is critically dependent on a single parameter 'beta' whose value, the authors claim, controls the switch from value-coding to choice-coding. However, the precise definition/interpretation of 'beta' seems inconsistent in different parts of the text. I elaborate on this issue in sub-points (1a-b) below:

1a). For instance, in the equations of the main text (Equations 1-3), 'beta' is used to denote the coupling from the excitatory units (R) to the disinhibitory units (D) in Equations 1-3. However, in the main figures (Fig 2) and in the methods (Equation 5-8), 'beta' is instead used to refer to the coupling between the disinhibitory (D) and the inhibitory gain control units (G). Based on my reading of the text (and the predominant definition used by the authors themselves in the main figures and the methods), it seems that 'beta' should be the coupling between the D and G units.

1b). A more general and critical issue is the failure to clearly specify whether this coupling of D-G units (parameterized by 'beta') should be interpreted as a 'functional' one, or an 'anatomical' one. A straightforward interpretation of the model equations (Equations 5-8) suggests that 'beta' is the synaptic weight (anatomical coupling) between the D and G units/populations. However, significant portions of the text seem to indicate otherwise (i.e a 'functional' coupling). I elaborate on this in subpoints (i-iii) below:

(1b-i). One of the main claims of the paper is that the value of 'beta' is under 'external' top-down control (Figure 2 caption, lines 124-126). When 'beta' equals zero, the model is consistent with the previous DNM model (dynamic normalization, Louie et al 2011), but for moderate/large non-zero values of 'beta', the network exhibits WTA dynamics. If 'beta' is indeed the anatomical coupling between D and G (as suggested by the equations of the model), then, are we to interpret that the synaptic weight between D-G is changed by the top-down control signal within a trial? My understanding of the text suggests that this is not in fact the case. Instead, the authors seem to want to convey that top-down input "functionally" gates the activity of D units. When the top-down control signal is "off", the disinhibitory units (D) are "effectively absent" (i.e their activity is clamped at zero as in the schematic in Fig 2B), and therefore do not drive the G units. This would in-turn be equivalent to there being no "anatomical coupling" between D and G. However when the top-down signal is "on", D units have non-zero activity (schematic in Fig 2B), and therefore drive the G units, ultimately resulting in WTA-like dynamics.

(1b-ii). Therefore, it seems like when the authors say that beta equals zero during the value coding phase they are almost certainly referring to a functional coupling from D to G, or else it would be inconsistent with their other claim that the proposed model flexibly reconfigures dynamics only through a single top-down input but without a change to the circuit architecture (reiterated in lines 398-399, 442-444, 544-546, 557-558, 579-590). However, such a 'functional' definition of 'beta' would seem inconsistent with how it should actually be interpreted based on the model equations, and also somewhat misleading considering the claim that the proposed network is a biologically realistic circuit model.

(1b-iii). The only way to reconcile the results with an 'anatomical' interpretation of 'beta' is if there is a way to clamp the values of the 'D' units to zero when the top-down control signal is 'off'. Considering that the D units also integrate feed-forward inputs from the excitatory R units (Fig 2, Equations 1-3 or 5-8), this can be achieved either via a non-linearity, or if the top-down control input multiplicatively gates the synapse (consistent with the argument made in lines 115-116 and 585-586 that this top-down control signal is 'neuromodulatory' in nature). Neither of these two scenarios seems to be consistent with the basic definition of the model (Equations 1-3), which therefore confirms my suspicion that the interpretation of 'beta' being used in the text is more consistent with a 'functional' coupling from D to G.

2) The main contribution of the manuscript is to integrate the characteristics of the dynamic normalization model (Louie et al, 2011) and the winner-take-all behavior of recurrent circuit models that employ mutual inhibition (Wang, 2008), into a circuit motif that can flexibly switch between these two computations. The main ingredient for achieving this seems to be the dynamical 'gating' of the disinhibition, which produces a switch in the dynamics, from point-attractor-like 'stable' dynamics during value coding to saddle-point-like 'unstable' dynamics during categorical choice coding. While the specific use of disinhibition to switch between these two computations is new, the authors fail to cite previous work that has explored similar ideas that are closely related to the results being presented in their study. It would be very useful if the authors can elaborate on the relationship between their work and some of these previous studies. I elaborate on this point in (a-b) below:

2a) While the authors may be correct in claiming that RNM models based on mutual inhibition are incapable of relative value coding, it has already been shown previously that RNM models characterized by mutual inhibition can be flexibly reconfigured to produce dynamical regimes other than those that just support WTA competition (Machens, Romo & Brody, 2005). Similar to the behavior of the proposed model (Fig 9), the model by Machens and colleagues can flexibly switch between point-attractor dynamics (during stimulus encoding), line-attractor dynamics (during working memory), and saddle-point dynamics (during categorical choice) depending on the task epoch. It achieves this via a flexible reconfiguration of the external inputs to the RNM. Therefore, the authors should acknowledge that the mechanism they propose may just be one of many potential ways in which a single circuit motif is reconfigured to produce different task dynamics. This also brings into question their claim that the type of persistent activity produced by the model is "novel", which I don't believe it is (see Machens et al 2005 for the same line-attractor-based mechanism for working memory)

2b) The authors also fail to cite or describe their work in relation to previous work that has used disinhibition-based circuit motifs to achieve all 3 proposed functions of their model - (i) divisive normalization (Litwin-Kumar et al, 2016), (ii) flexible gating/decision making (Yang et al, 2016), and working memory maintenance (Kim & Sejnowski,2021)

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

This work dives into the inner molecular workings of viruses such as yellow fever, Zika, and tick borne encephalitis. Due to their pathogenic nature, these are active targets for drug development, and motivated by this, the authors set out to search for so-called "cryptic" binding pockets, concealed from the protein surface and therefore often missed. Using atomistic computer simulations of viral rafts embedded in lipid membranes, the authors present new methodology to detect and characterise structural and electrostatic features of viral envelope proteins. By mixing in a small organic co-solvent (benzene) that acts as a drug proxy, structural fluctuations are enhanced, which reveal hitherto hidden binding pockets. The authors convincingly show that this perturbation has only a minute effect on protein secondary structure. The technique revealed a new cryptic binding pocket that is well conserved across multiple flaviviruses.

The cryptic site involves four potentially charged residues and to understand their interplay, constant pH molecular dynamics simulations are combined with a detailed structural and electrostatic analysis of the binding pocket.<br /> Due it's multi-dimensional nature, the response to a possible pH change is a complex process and the authors present a compelling analysis involving charge states, inter-residue distances (reduced using PCA), and structural features of the pocket. An important conclusion is that the role of histidine is less important than previously thought: the pH dependent behaviour is a collective property of the pocket.

This study is an important contribution to computer aided drug-design. In particular, using co-solutes to induce structural fluctuations seems very helpful for uncovering new binding sites. Of equal importance are methodology to analyse complex trajectories. This work is a good example of how multiple dimensions can be reduced and rationalised using e.g. solvent accessibly surface area (SASA), radius of gyration, net-charge, and principal component analysis. There are likely several other properties that could aid in this rationalising and the present work is a solid platform for exploring these.

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

Rodriguez et al. develop a nonlinear ordinary differential equation model of hematopoiesis under normal and chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) conditions, incorporating feedback control, lineage branching, and signaling between normal and CML cells. Design space analysis is used to identify viable models of cell-cell signalling interaction. Data from mouse models are used to refine the set of cell-cell interactions considered viable, resulting in a novel feedback-feedforward model. Through this framework, the response to tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy is analysed. Model behaviour is qualitatively consistent with experimental data from mouse models, and clinical data. In particular, the model demonstrates varying responses to tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy across a range of parameter sets consistent with "normal" hematopoietic cell counts; and predicts that a relatively high proportion of leukemic hematopoietic stem cells is a contributor to (though does not guarantee) primary tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance, consistent with experimental and clinical data.

Strengths:<br /> Mathematical modelling in the work is validated using both experimental and clinical data.

The approach to model selection and identification of reasonable parameter regions is interesting and appealing, particularly in the context of modelling processes such as CML which can exhibit significant heterogeneity between patients.

I expect that this work will be useful to the community, as the approach employed in this work could be readily adapted to study other similar problems (for example, different conditions or treatments), provided that suitable experimental and/or clinical data are collected or available.

The work is supported by extensive supplementary material, clearly documenting in detail the techniques involved and assumptions made.

Weaknesses:<br /> Clinical data from CML patients treated with TKI therapy is limited (n=21).

As acknowledged by the authors, there are some physiological aspects that may be important that are not modelled; including stem cell-niche interactions in the bone marrow microenvironment, and interactions with immune cells.

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

In this study Cook and Ryan examine, at physiological temperatures, the sensitivity of neurotransmitter release to external calcium concentrations close to physiological ones. Using hippocampal neurons in culture, field potential-based stimulation, a spatially confined genetically encoded calcium indicator (GCaMP6f) as well as fluorescent reporters of exocytosis and extracellular glutamate, the authors show that as extracellular calcium concentrations are reduced from 2.0, to 1.2 and finally to 0.8 mM, a disproportional fraction of presynaptic terminals cease to respond, as evidenced by no elevations in intracellular calcium concentrations, no detectable exocytosis or changes in extracellular glutamate. The phenomenon is quantitively modulated by blocking particular types of calcium channels, but is qualitatively conserved across all tested conditions. Finally, the authors show that effects of lower extracellular calcium concentrations can be mimicked by applying Baclofen, an agonist of type B GABA receptors. The authors reveal the sensitivity of all-or none calcium influx and exocytosis near extracellular calcium physiological set points and highlight the potential importance of this sensitivity as an effective control point for neural circuit modulation.

The findings described in the manuscript are potentially important as they seem to uncover a new, yet undescribed, all-or none (binary) phenomenon in the field of synaptic neuroscience, that is, of individual presynaptic terminals moving between two 'states' - 'active' and 'silenced'- which are set somehow by levels of extracellular calcium concentrations. Moreover, this dependency is observed at extracellular calcium concentrations that are quite close to the physiological concentration set point. The use of multiple reporters (intracellular calcium concentrations, synaptic vesicle fusion and extracellular glutamate) strengthens the validity of the observations.

On the other hand, there are two major points that need to be addressed.

The first is that alternative explanations should be ruled out more convincingly, first and foremost the matter of membrane excitability. Two observations are relevant here: The qualitative preservation of the phenomenon when two types of voltage gated calcium channels are blocked separately, and the large heterogeneity of the % of silenced boutons among neurons at a given extracellular calcium concentrations, which is at least as great as the range of modulation of the % of silenced synapses by extracellular calcium concentrations at single neurons. One then wonders if the findings might be attributed to a) the fidelity of the field potential-based stimulation system, that is, the degree to which neurons track the stimuli trains; b) the heterogeneity of neurons in this regard, c) this fidelity at different extracellular calcium concentrations for different neurons, and d) the identity of presynaptic sites analyzed in one run (are they all part of the same axon?). Along these lines, there is an assumption that the field potential-based stimulation system is the sole driver of excitation in these networks, which is reasonable given that excitatory synaptic transmission is mostly blocked pharmacologically (by CNQX and APV). Inhibitory transmission, however, was not blocked and thus, there is no guarantee that the inhibitory input neurons receive and its modulation by extracellular calcium does affect the degree to which neurons fire precisely and reliably at 20 Hz at all conditions. If it could be shown, at least for a substantial subset of the data, that all terminals analyzed for a particular neuron are part of an unambiguously identified axon stretch, with no branches (potential conduction failure points) and still demonstrate the claimed heterogeneity, this potential confound would be less of an issue.

The second issue relates to the ties made to neuromodulation. In spite of the title, introduction and discussion, not a single neuromodulator (such as dopamine, acetylcholine, noradrenaline, serotonin) was tested, only baclofen, which as a derivative of GABA, activates GABAB receptors, not receptors of canonical neuromodulators. The title of this manuscript is therefore not appropriate.

-

-

www.medrxiv.org www.medrxiv.org

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

The authors describe a machine learning method for classifying the geographic origin of a Salmonella enterica isolate based on its whole-genome sequencing data. This is done at a continent, region, and country level, and the method is shown to be robust to phylogenetic diversity, temporal trends, and possibly some amount of mislabelling (but please see the first concern below). The authors demonstrate that their pipeline produces results in 5 minutes or less, which makes it applicable to many public health microbiology settings.

Some clear strengths of the paper include:<br /> - the use of a hierarchical classification method, which ensures that only those samples that can be unambiguously classified as belonging to a specific region can get assigned to a sub-region within that region (e.g. continent to country)<br /> - leveraging the UKHSA dataset going back nearly a decade, and containing a comprehensive record of all clinically detected Salmonella enterica infections, which mitigates potential biases and ensures a maximal geographic coverage<br /> - making all the data (microreact) and the source code (GitHub) public, which facilitates replication as well as enables other researchers and public health microbiologists to use the trained models directly on their own data<br /> - the use of unitigs as the basis for prediction, which are more informative than K-mers yet more straightforward to identify than SNPs or gene alleles.

There are several methodological concerns that should ideally be addressed:<br /> - in addition to the more complex situation of a tourist visiting country A and consuming food from country B, it would be good to rule out a simpler one of the tourist visiting both countries on the same trip (including via a stopover at an airport); the authors should elaborate on the plausibility of missing data on such multi-country trips and their frequency based on the available travel data<br /> - similarly, there appears to be an underlying assumption that the UK is never at the origin of a Salmonella enterica infection in the dataset selected; the authors should explain why that is a reasonable assumption for this dataset<br /> - the increase of infection incidence during the summer months might be at least partly attributable to a greater number of trips abroad during that period - if the authors have corrected their data for this, they should explicitly say so<br /> - lastly, in discussing the outbreak due to Polish eggs, it should be possible to check explicitly what fraction of the training data may have originated from this outbreak to see if this is sufficient to explain the observed poor prediction

Overall, this is a paper representing a substantial body of work and combining algorithmic advances with practical utility given the rapid turnaround time. It is likely to be generalisable to other pathogens of public health importance and to become integrated into standard protocols for outbreak origin tracing.

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

Using viral tracing and single-cell transcriptome profiling the authors investigated the electrophysiologic, morphologic, and physiologic roles for subsets of cardiac-specific neurons and found evidence that three adrenergic stellate ganglionic neuron subtypes innervate the heart.

The presented findings provide relevant insights into the properties of neurons modulating cardiac sympathetic control. The findings might open up new avenues to targeted modulation of cardiac sympathetic control. Additional insights from various models addressing for example ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy might allow to development of targeted therapies for various patient populations in the future.

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

The study aimed at the identification of functional micro-peptides encoded by transcripts previously annotated as long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs). The authors pre-selected 10 candidates out of the ~500 zebrafish lncRNA data set based on their engagement with the ribosome (by ribosome profiling data) and their expression in the embryonic brain. By performing an F0 CRISPR/Cas9 screen coupled with embryonic behavioral assays, two transcripts encoding sequence-related micro-peptides were identified. Using a set of stable mutant alleles, the authors showed that mutations specifically affecting the open reading frame (ORF) of the putative micro-peptides cause changes in embryonic behavior when compared to wild-type embryos or embryos with mutations in the non-coding regions of the tested transcripts. The locomotor hyperactivity phenotype was even stronger in double homozygous mutants suggesting a redundant function of both micro-peptides. The authors demonstrated that the behavioral phenotype of one of the mutants was rescued by the transgene expression of the coding sequence (CDS). Sequence analyses of both peptides revealed their conservation and homology to the human non-histone chromosomal proteins (HMGN1 proteins). The authors demonstrated that the micro-peptide mutants exhibit changes in chromatin accessibility for transcription factors modifying neural activation, dysregulation of gene expression programs, and changes in oligodendrocyte and cerebellar cell states during development.

The study presents an important discovery of two sequence-related micro-peptides with important and potentially conserved functions during development. While it is still unclear how the micro-peptides act in the cell, it is evident that they are key regulators of cellular states. Whereas the study is well done, the data presentation should be improved as several important details were omitted.

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

K. Vandelannoote and collaborators report on using spatially-localized possum feces investigated for Mycobacterium ulcerans, as a proxy for cases of Buruli ulcer, South Australia. The report is a contributive, enforcing survey of animal excreta and is based on strong pieces of evidence.

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):<br /> <br /> The manuscript by Francou et al investigated cellular mechanisms of epiblast ingression during mouse gastrulation. The authors wanted to know whether/how epiblast cell-cell junctional dynamics correlate with apical constriction and subsequent ingression. Because mouse gastrula adopts an inverted-cup morphology (as a result of differential invasive behavior of polar and mural trophoblast cells), epiblast cells are located in the innermost position and are difficult to image. This is more so when one wants to perform live imaging of epiblast cells' apical surface. The authors tackled such problems/limitations by using a combination of ZO-1 GFP line, confocal time-lapse microscopy, fixed embryo immunostaining, and Crumbs2 mutant embryos. The authors observed that apical constriction was associated with cell ingression, that this constriction occurred in a pulsed fashion (i.e., 2-4 cycles with phases of contraction and expansion, eventually leading to reduction of apical surface and ingression), that this constriction took place asynchronously (i.e., neighboring epiblast cells did not exhibit coordinated behavior) and that junctional shrinkage during apical constriction also occurred in a pulsed and asynchronous manner. The authors also investigated localization/co-localization of several apical proteins (Crumbs2, Myosin2B, pMLC, ppMLC, Rock1, F-actin, PatJ, and aPKC) in fixed samples, uncovering somewhat reciprocal distribution of two groups of proteins (represented by Myosin2B in one group, and Crumbs2 in the other). Finally, the authors showed that Crumbs2 -/- embryos had disturbed actomyosin distribution/levels without affecting junctional integrity (partially explaining the ingression defect reported in Crumbs2 -/- mutant embryos). Overall, this manuscript offers high-quality live imaging data on the dynamic remodeling of epiblast apical junctions during mouse gastrulation. It would be interesting to see whether phenomena reported in this manuscript can be extended to the entire primitive streak (or are they specific only to a subset of mesoderm precursors) and to the entire period of mesendoderm formation. More importantly, it would be interesting to see whether the ingression behavior seen here is representative of all eutherian mammals regardless of their gastrular topography.

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

In this manuscript, a cytosolic extract of porcine oocytes is prepared. To this end, the authors have aspirated follicles from ovaries obtained from by first maturing oocytes to meiose 2 metaphase stage (one polar body) from the slaughterhouse. Cumulus cells (hyaluronidase treatment) and the zona pellucida (pronase treatment) were removed and the resulting naked mature oocytes (1000 per portion) were extracted in a buffer containing divalent cation chelator, beta-mercaptoethanol, protease inhibitors, and a creatine kinase phosphocreatine cocktail for energy regeneration which was subsequently triple frozen/thawed in liquid nitrogen and crushed by 16 kG centrifugation. The supernatant (1.5 mL) was harvested and 10 microliters of it (used for interaction with 10,000 permeabilized boar sperm per 10 microliter extract (which thus represents the cytosol fraction of 6.67 oocytes).

The sperm were in this assay treated with DTT and lysoPC to prime the sperm's mitochondrial sheath.

After incubation and washing these preps were used for Western blot (see point 2) for Fluorescence microscopy and for proteomic identification of proteins.

Points for consideration:

1) The treatment of sperm cells with DTT and lysoPC will permeabilize sperm cells but will also cause the liberation of soluble proteins as well as proteins that may interact with sperm structures via oxidized cysteine groups (disulfide bridges between proteins that will be reduced by DTT).

2) Figure 3: Did the authors really make Western blots with the amount of sperm cells and oocyte extracts as the description in the figures is not clear? This point relates to point 1. The proteins should also be detected in the following preparations (1) for the oocyte extract only (done) (2) for unextracted nude oocytes to see what is lost by the extraction procedure in proteins that may be relevant (not done) (3) for the permeabilized (LPC and DTT treated and washed) sperm only (not done) (4) For sperm that were intact (done) (5) After the assay was 10,000 permeabilized sperm and the equivalent of 6.67 oocyte extracts were incubated and were washed 3 times (or higher amounts after this incubation; not done). Note that the amount of sperm from one assay (10,000) likely will give insufficient protein for proper Western blotting and or Coomassie staining. In the materials and methods, I cannot find how after incubation material was subjected to western blotting the permeabilized sperm. I only see how 50 oocyte extracts and 100 million sperm were processed separately for Western blot.

3) Figures 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 see point 2. I do miss beyond these conditions also condition 1 despite the fact that the imaged ooplasm does show positive staining.

4) These points 1-3 are all required for understanding what is lost in the sperm and oocyte treatments prior to the incubation step as well as the putative origin of proteins that were shown to interact with the mitochondrial sheath of the oocyte extract incubated permeabilized sperm cells after triple washing. Is the origin from sperm only (Figs 5-8) or also from the oocyte? Is the sperm treatment prior to incubation losing factors of interest (denaturation by DTT or dissolving of interacting proteins pre-incubation Figs 3-8)?

5) Mass spectrometry of the permeabilized sperm incubated with oocyte extracts and subsequent washing has been chosen to identify proteins involved in the autophagy (or cofactors thereof). The interaction of a number of such factors with the mitochondrial sheath of sperm has been shown in some cases from sperm and others for an oocyte origin. Therefore, it is surprising that the authors have not sub-fractionated the sperm after this incubation to work with a mitochondrial-enriched subfraction.

I am very positive about the porcine cell-free assay approach and the results presented here. However, I feel that the shortcomings of the assay are not well discussed (see points 1-5) and some of these points could easily be experimentally implemented in a revised version of this manuscript while others should at least be discussed.

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

The authors tried to study the role of the cylicin gene in sperm formation and male fertility. They used the Crispr/cas 9 to knockout two mouse cylicin genes, cylicin 1 and cylicin 2. They used comprehensive methods to phenotype the mouse models and discovered that the two genes, particularly cylicin 2 are essential for sperm calyx formation. They further compared the evolution of the two genes. Finally, they identified mutations of the genes in a patient. The major strengths are the high quality of data presented, and the conclusion is supported by their findings from the animal models and patients. The major weakness is that the study is descriptive: no molecular mechanism studies were conducted or proposed, limiting its impact on the field.

-

-

www.shopbrodart.com www.shopbrodart.com

-

Brodart Full-Length Single Charging Tray<br /> Full- length charging tray with 1,000-card capacity<br /> Price: $96.32

- Adjustable steel follower block with automatic lock

- Felt pads on tray bottom protect desktop

- Full-length charging tray for countertop use

- 4"H x 4"W x 16"D

- Holds 1,000 5"H x 3"W cards

- Includes antimicrobial finish

- Made in the USA

See also: https://hypothes.is/a/ao89RMQmEe2zIvsu3lf6kw for a smaller version

-

-

www.shopbrodart.com www.shopbrodart.com

-

Brodart Mini Single Charging Tray Mini single charging tray with 600-card capacity More Info Price: $76.76

- Adjustable steel follower block with automatic lock

- Felt pads on tray bottom protect desktop

- Mini charging tray fits on your lap

- 4"H x 4"W x 8"D

- Holds 600 5"H x 3"W cards

- Includes antimicrobial finish

- Made in the USA

This could be used for a modern day Memindex box for portrait oriented 3 x 5" index cards.

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

In this manuscript, the authors characterize antigen binding sites, mechanism of action, and in vivo efficacy of neutralizing monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) previously isolated from New World hantavirus survivors. Both hantavirus species-specific mAbs and broadly neutralizing hantavirus mAbs are analyzed.

The strengths of the manuscript are the presentation of both in vitro and in vivo data for mAbs that have different antigen binding sites and mechanisms of neutralization. Weaknesses include a lack of authentic virus experiments for the in vitro data.

The impact of the work on the field is the identification of different neutralizing sites on hantavirus glycoproteins in species-specific and broadly reactive mAbs. There are also interesting data on loss of broadly neutralizing activity of mAbs after reversion to the germline sequence.

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

Head-fixed preparations should always be conceived more as a necessity (for example, to avoid damaging expensive lab equipment) than as a final path towards which the entire field of neuroscience must go. The ideal will always be to move towards a more naturalistic and ecological approach to understanding behavior. Said that. The Davis Rig seems to be a thing of the past, welcome the Open-Source Head-fixed Rodent Behavioral Experimental Training System (OHRBETS). OHRBETS represents a significant advantage over the Davis Rig equipment to measure oromotor palatability responses in a brief access test, to perform positive and negative reinforcement, and even real-time place preference in a head-fixed preparation.

This is a well-written manuscript; the work and results are impressive. The manuscript is quite relevant to the Neuroscience field and will be of general interest. The experiments were carefully done. It is expected that OHRBETS will be widely used in multiple Neuroscience labs.

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

In this manuscript, Guinet and colleagues explore the impact of endoparasitoid lifestyle in Hymenopterans on endogenization and domestication of viruses. Using a well-structured bioinformatic pipeline, they show that an endoparasitoid lifestyle promotes viral endogenization and domestication, particularly for dsDNA viruses. In their discussion, they provide multiple discussion points to hypothesize why this could be the case. It is, to my knowledge, one of the first to link life history traits of insects to particular bias in the genomic endogenization of viruses, which has implications for virology and host-parasite interaction at large.

The manuscript is well-written and structured. The amount of data generated and analyzed is impressive, and the authors have carefully set up their analysis. I have no reasons to doubt any of the analyses the authors have conducted on the output of the screening pipeline set up to discover and characterize endogenous viral elements. I would, however, have appreciated a more thorough investigation on the impact of the scoring system for EVE detection (Scaffold endogenization score), which strongly shapes the dataset used for the analysis, and thus might introduce biases. While I completely understand the need for a scoring system and agree that the parameters used seem reasonable, these are new for the field, and their impact has not been properly explored here. The authors have chosen to focus on a conservative threshold of EVEs scored above D (see Table S2): I wonder what the picture would be if they included all potential EVEs, even poorly scored. How dependent are the results of this unvalidated scoring system? I know several proven EVEs in mosquitoes (confirmed in vivo) that would have been poorly scored and excluded here. By being sure to exclude false positives, the authors may have biased their dataset in ways that influence the results.

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

Initially, Salas-Lucia et al examined the effect of deiodinase polymorphism on thyroid hormone-medicated transcription using a transgenic animal model and found that the hippocampus may be the region responsible for altered behavior. Then, by changing to topic completely, they examined T3 transport through the axon using a compartmentalized microfluid device. By using various techniques including an electron microscope, they identified that T3 is uptaken into clathrin-dependent, endosomal/non-degradative lysosomes (NDLs), transported in the axon to reach the nucleus and activate thyroid hormone receptor-mediated transcription.

Although both topics are interesting, it may not be appropriate to deal with two completely different topics in one paper. By deleting the topic shown in Table 1, Figure 1, and Figure 2, the scope of the manuscript can be more clear.

Their finding showing that triiodothyronine is retrogradely transported through axon without degradation by type 3 deiodinase provides a novel pathway of thyroid hormone transport to the cell nucleus and thus can contribute greatly to increasing our understanding of the mechanisms of thyroid hormone action in the brain.

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

This paper addresses the impact of non-linear protein degradation on the precision of morphogen gradients. Since the predominant model for the formation of morphogen gradients is a production/diffusion/degradation model understanding the contribution of degradation is an important question. This paper investigates the properties of the simplest and most general mathematical model for gradient formation. As such, this work is of interest. The main conclusion of the paper is that non-linear protein degradation has little impact on the precision of the morphogen gradient near the source of production of the morphogen and it reduces precision far away from the source. These conclusions are supported by the mathematical analysis presented. The paper is a difficult read for people unfamiliar with the current literature.

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

The manuscript by Chen et al shows solid evidence that canine origin influenza viruses are evolving towards a more mammalian adapted phenotype. The data also show that humans may lack proper protection against these viruses if they were to evolve more prone to cross to humans. There are some aspects of the ms that need to be addressed: 1) The investigators should run neuraminidase inhibition assays to established the level of cross reactivity of human sera to the canine origin NA (one of reasons proposed as to the lower impact of the H3N2 pandemic was the presence of anti0N2 antibodies in the human population), 2) please tone down the significance of ferret-to-ferret transmission as a predictor of human-to-human transmission. Although flu viruses that transmit among humans do show the same capacity in ferrets, the opposite is NOT always true.

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

The manuscript adequately demonstrates that genomic instability is maintained in HGSOC tumourspheres. The use of 3-dimensional HGSOC models to more greatly resemble the in vivo environment has been used for more than a decade, but this is the first demonstration using a variety of genomic assessment tools to show genomic instability in the HGSOC tumoursphere model. It is clearly demonstrated that these HGSOC tumourspheres represent copy number variations similar to information in public datasets (TCGA, PAWG, BriTROC-1) and that cellular heterogeneity is present in these tumourspheres. The simple steps outlined to establish and passage tumourspheres will benefit the field to further study mechanisms of genomic instability in HGSOC.

A weakness of the manuscript is the lack of operational definitions for what constitutes an organoid and an appropriate definition to distinguish genomic instability from chromosomal instability (a distinct type of genomic instability). Line 147 states "As PDOs consist of 100% tumour cells...", although this does not appear to have been established by any assessment. This limited characterization of the 3D model is a weakness since no data is provided on whether the tumourspheres constitute only a single cell type (as indicated on line 147) or multiple cell types (e.g., HGSOC cell, mesothelial cells) using markers beyond p53 expression. Based on this information, this model cannot be called a PDO, rather it should be referred to as a tumoursphere.

Chromosome instability (CIN) is a type of genomic instability that is broadly defined as an increased rate of chromosome gains or losses and is best identified through analysis of single cells (e.g., karyotype analysis), something that bulk whole genome sequencing cannot determine since it is a reflection of cell populations and not individual cells. While the data demonstrate genomic instability is retained in the tumourspheres, and chromosome losses or copy-number amplifications were observed using single-cell whole genome sequencing, evaluation of samples from the same patient over time was not evaluated. While there is evidence to support CIN in these samples, in agreement with other published work that has demonstrated CIN in >95% of HGSOC samples analyzed at the single-cell level, this work is not conclusive. The title of the manuscript should be modified to more accurately represent what the evidence supports.

An additional weakness is missing information (e.g., Figure 1d, Supplementary Figure 3b, and Supplementary Table 4 were not included in the manuscript; the 13 anticancer compounds used to test drug sensitivity are not indicated) making an assessment of the data impossible, and assessment of some conclusions difficult.

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

This manuscript by Geisler and colleagues used suppressor genetics to identify suppressors of the sma-5(n678) allele, which results in a defective gut endotube (an IF layer just under the microvillar structure), small body size, slow development, and short life span. The authors identified an internal deletion allele in ifb-2, which stunningly rescues all of the phenotypes listed above (despite the apparent absence of an endotube). This suppression is also observed with a previously characterized knockout allele. Conversely, this allele also suppresses analogous defects that result from mutations in the ifo-1 gene and bbln-1.

This is an exceptionally rigorous set of experiments, beautifully described in a clear manuscript illustrated by nicely constructed figures. The overall finding, that some IF mutations result in toxic aggregates that can be eliminated by the loss of a single IF protein is interesting both from a fundamental understanding of IF networks and its clinical implications. With one minor exception, the conclusions are well supported by the data presented.

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

In this manuscript, Chan and collaborators investigate the role of CDPK1 in regulating microneme trafficking and exocytosis in Toxoplasma gondii. Micronemes are apicomplexan-specific organelles localized at the apical end of the parasite and depending on cortical microtubules. Micronemes contain proteins that are exocytosed in a Ca²+-dependent manner and are required for T. gondii egress, motility, and host-cell invasion. In Apicomplexa, Ca²+ signaling is dependent on Ca²+-dependent protein kinases (CDPKs). CDPK1 has been demonstrated to be essential for Ca²+-stimulated micronemes exocytosis allowing parasite egress, gliding motility, and invasion. It is also known that intracellular calcium storages are mobilized following a cyclic nucleotide-mediated activation of protein kinase G. This step, occurs upstream of CDPK1 functions. However, the exact signaling pathway regulated by CDPK1 remains unknown. In this paper, the authors used phosphoproteomic analysis to identify new proteins phosphorylated by CDPK1. They demonstrated that CDPK1 activity is required for calcium-stimulated trafficking of micronemes to the apical end, depending on a complex of proteins that include HOOK and FTS, which are known to link cargo to the dynein machinery for trafficking along microtubules. Overall, the authors identified evidence for a new protein complex involved in microneme trafficking through the exocytosis process for which circumstantial evidence of its functionality is demonstrated here.

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

Acetylcholine and Norepinephrine are two of the most powerful neuromodulators in the CNS. Recently developments of new methods allow monitoring of the dynamic changes in the activity of these agents in the brain in vivo. Here the authors explore the relationship between the dynamic changes in behavioral states and those of ACh and NE in the cortex. Since neuromodulatory systems cover most of the cortical tissue, it is essential to be able to monitor the activity of these systems in many cortical areas simultaneously. This is a daunting task because the axons releasing NE and ACh are very thin. To my knowledge, this study is the first to use mesoscopic imaging over a wide range of the cortex at the single axon resolution in awake animals. They find that almost any observable change in behavioral state is accompanied by a transient change in the activity of cortical ACh and NE axonal segments. Whisking is significantly correlated with ACh and NE. The authors also explore the spatial pattern of activity of ACh and NE axons over the dorsal cortex and find that most of the dynamics is synchronous over a wide spatial scale. They look for deviation from this pattern (which I will discuss later). Lastly, the authors monitor the activity of cortical interneurons capable of releasing ACh.

Comments:<br /> 1. On a broad overview, I find the discussion of behavioral states, brain states, and neuromodulation states quite confusing. To begin with, I am not convinced by the statement that "brain states or behavioral states change on a moment-to-moment basis." I find that the division of brain activity into microstates (e.g., microarousal) is counterproductive. After all, at the extreme, going along this path, we might eventually have an extremely high dimensional space of all neuronal activity, and any change in any neuron would define a new brain state. Similarly, mice can walk without whisking, can whisk without walking, can walk and whisk, are all these different behavioral states? And if so, are they all associated with different brain states? Most importantly, in the context of this manuscript, one would expect that different states (brain, behavior) would be associated with at least four potential states of the ACh x NE system (high ACh and High NE, High ACh and Low NE, etc.). However, the reported findings indicate that the two systems are highly synchronized (or at least correlated), and both transiently go on with any change from a passive state to an active state. Therefore, the manuscript describes a rather confined relationship of the neuromodulation systems with the rather rich potential of brain and behavioral states. Of course, this is only my viewpoint, and the authors are not obliged to accept it, but they should recognize that the viewpoint they take for granted is not shared by all and consider acknowledging it in the manuscript.<br /> 2. Most of the manuscript (bar one case) reports nearly identical dynamics of ACh and NE. Is that a principle? What makes these systems behave so similarly? Why have two systems that act nearly the same? Still, if there is a difference, it is the time scale of the ACh compared to the NE. Can the authors explain this difference or speculate what drives it?<br /> 3. Whisker activity explains most strongly the neuromodulators dynamics, but pupil dilation almost does not (in contrast to many previous reports including reports of the same authors). If I am not mistaken, this was nearly ignored in the presentation of the results and the discussion section. Could the author elaborate more on what is the reason for this discrepancy?<br /> 4. I find the question of homogenous vs. heterogenous signaling of both the ACh and NE systems quite important. It is one thing if the two systems just broadcast "one bit" information to the whole brain or if there are neuromodulation signals that are confined in space and are uncorrelated with the global signal. However, the way the analysis of this question is presented in the manuscript is very difficult to follow, and eventually, the take-home message is unclear. The discussion section indicates that the results support that beyond a global synchronized signal, there is a significant amount of heterogeneous activity. I think this question could benefit from further analysis. I suggest trying to demonstrate more specific examples of axonal ROIs where their activity is decorrelated with the global signal, test how consistent this property is (for those ROIs), and find a behavioral parameter that it predicts. Also, in the discussion part, I am missing a discussion of the potential mechanism that allows this heterogeneity. On the one hand, an area may receive NE/ACh innervation from different BF/LC neurons, which are not completely synchronized. But those neurons also innervate other areas, so what is the expected eventual pattern? Also, do the results support neuromodulation control by local interneuron circuits targeting the axons (as is the case with dopaminergic axons in the Basal Ganglia)?<br /> 5. The axonal signal seems to be very similar across the cortex. I am not sure this is technically possible, but given that NE axons are thin and non-myelinated and taking advantage of the mesoscopic scale, could the author find any clue for the propagation of the signal on the rostral to caudal axis?<br /> 6. While the section about local VCIN is consistent with the story, it is somehow a sidetrack and ends the manuscript on the wrong note. I leave it to the authors to decide but recommend them to reconsider if and where to include it. Unfortunately, the figure attached was on a very poor resolution, and I could not look into the details, so I am afraid that I could not review this section properly.

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

This manuscript describes McSC states and McSC function during regeneration in zebrafish using both a scRNAseq timecourse and classic zebrafish experimentation, including lineage tracing and mutant lines. Altogether this study provides a more holistic look at pigment regeneration following injury and helps to validate the role of signaling pathways implicated in McSC biology by previous studies. The major question addressed by this manuscript is whether McSC heterogeneity can explain the highly regenerative nature of the zebrafish pigmentary system. The observations reported in this manuscript confirm this view, eloquently using a time course of single-cell transcriptomics for predictive purposes followed up by mechanistic studies to confirm the fate of different McSC subclusters. This study very nicely complements and extends our current understanding of how McSCs function during regeneration and provides novel datasets for further interrogation. Perhaps the most exciting aspect of the data is the identification of a novel marker (aox5) to identify self-renewing McSCs; this tool could be employed to identify these cells and address their potential in the context of expanding these cells for therapeutic purposes or address their contribution as melanoma stem cells. This study will be of general interest to researchers interested in pigment regeneration, stem cell-based therapeutics for pigment disorders, and the basic biology of stem cells and their heterogeneity.

While this paper certainly extends previous observations of McSCs, the idea of McSC heterogeneity is not necessarily novel. In mouse, KIT-dependent and KIT-independent McSC populations have been identified (Ueno 2015) as well as other McSC subpopulations with different potentials (CD34+/-, Joshi 2019). While this manuscript does a much more comprehensive job of describing this heterogeneity, which is fantastic, some of the previous literature on the topic could be better acknowledged and integrated. Despite this criticism, this manuscript provides the most comprehensive look to date at McSC dynamics across the regenerative period and provides ample datasets for secondary analyses to generate/confirm additional hypotheses.

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

In this study, the authors set out to study the requirement of the TATA binding protein (TBP) in transcription initiation in mESCs. To this end they used an auxin inducible degradation (AID) system. They report that by using the AID-TBP system after auxin degradation, 10-20% of TBP protein is remaining in mESCs. The authors claim that as, the observed 80-90% decrease of TBP levels are not accompanied by global changes in RNA polymerase II (Pol II) chromatin occupancy or nascent mRNA levels, TBP is not required for Pol II transcription. In contrast, they find that under similar TBP-depletion conditions tRNA transcription and Pol III chromatin occupancy were impaired. The authors also asked whether the mouse TBP paralogue, TBPL1 (also called TRF2) could functionally replace TBP, but they find that it does not. From these and additional experiments the authors conclude that redundant mechanisms may exist in which TBP-independent TFIID like complexes may function in Pol II transcription.

The major strengths of this manuscript are the numerous genome-wide investigations, such as many different CUT&Tag experiments, and NET-seq experiments under control and +auxin conditions and their analyses. Weaknesses lie in some experimental setups (i.e. overexpression of Halo-tagged TAFs), mainly in the overinterpretation (or misinterpretation) of the data and in the lack of a fair discussion of the obtained data in comparison to observations described in the literature. As a result, very often the interpretation of data does not fully support the conclusions.<br /> Nevertheless, the findings that 80-90% decrease in cellular TBP levels do not have a major effect on Pol II transcription are interesting, but the manuscript needs some tuning down of many of the authors' very strong conclusions, correcting several weaker points and with a more careful and eventually more interesting Discussion.

-

-

drive.google.com drive.google.comview40

-

persecute

迫害 (v.) to treat someone unfairly or cruelly over a long period of time because of their race, religion, or political beliefs, or to annoy someone by refusing to leave them alone

-

'>pat

吐 to eject (something) from the mouth

-

mantle

斗篷 a figurative cloak symbolizing preeminence or authority

-

batt;.1lion

營 a military unit composed of a headquarters and two or more companies, batteries, or similar units

-

flogged

鞭打 to beat with or as if with a rod or whip

-

counsel

協商 guarded thoughts or intentions

-

gnac,hing

咬牙切齒 to strike or grind (the teeth) together

-

leaven

酵 a substance (such as yeast) used to produce fermentation in dough or a liquid especially

-

mustard

芥末 a pungent yellow condiment consisting of the pulverized seeds of various mustard plants (such as Sinapis alba, Brassica juncea, and B. nigra) either dry or made into a paste or sauce (as by mixing with water or vinegar) and sometimes adulterated with other substances (such as turmeric) or mixed with spices

-

granary

糧倉 a storehouse for threshed grain

-

darncl

幾種通常多雜草的黑麥草(黑麥草屬)中的任何一種 any of several usually weedy ryegrasses (genus Lolium)

-

parched

因乾燥而皺縮 to become dry or scorched

-

thistles

薊 any of various prickly composite plants (especially genera Carduus, Cirsium, and Onopordum) with often showy heads of mostly tubular flowers

-

ra\ening

貪吃 to feed greedily

-

rend

撕裂 to perform an act of tearing or splitting

-

toii

辛勞 long strenuous fatiguing labor

-

mammc~n

財神爺 material wealth or possessions especially as having a debasing influence

-

sco" I

皺眉頭 to contract the brow in an expression of displeasure

-

synagogues

猶太教堂 the house of worship and communal center of a Jewish congregation

-

recompense

補償 to return in kind

-

porter

搬運工 a person who carries burdens

-

harlotry

淫亂 sexual profligacy

-

amiss

通過踩踏來壓碎、傷害或毀壞 to crush, injure, or destroy by or as if by treading

-

tramp l ed

通過踩踏來壓碎、傷害或毀壞 to crush, injure, or destroy by or as if by treading

-

pigeons

廣泛分佈的鳥類科(鴿科,鴿形目)中的任何一種,具有粗壯的身體、相當短的腿和光滑緊湊的羽毛 any of a widely distributed family (Columbidae, order Columbiformes) of birds with a stout body, rather short legs, and smooth and compact plumage

-

census

古羅馬用於人口統計的量詞 a count of the population and a property evaluation in early Rome

-

decree

an order usually having the force of law 有法律效力的命令

-

guile

詭計 trick

-

resurrection

1.the rising of Christ from the dead 2.the rising again to life of all the human dead before the final judgement 3.the state of one risen from the dead

復活、復興、恢復、耶穌復活

-

tombs

An excavation in which a corpse is buried. 墓穴

-

\eil

A length of cloth worn by women as a covering for the head and shoulders and often especially in Eastern countries for the face. 面紗

-

abusivcl)

Using or involving physical violence or emotional cruelty. 爛用地、辱罵地、虐待地

-

blasphemed

To speak in way that shows irreverence for God or something sacred 褻瀆

-

gall

Something bitter to endure 膽汁、苦味

-

crucified

To put to death by nailing or binding the wrists or hands and feet to a cross 釘在十字架上

-

malice

Desire to cause pain, injury, or distress to another. 怨恨、惡意

-

notorious

Generally known and talked of 惡名昭彰的、眾人皆知的

-

multitude

A state of being many 大量、多數、群眾

-

was accustomed to

習慣於

-

testimony

A solemn declaration usually made orally by a witness under oath in response to interrogation by a lawyer or authorized public official. 證據、證明

-

-

books.googleusercontent.com books.googleusercontent.comcontent1

-

2 3-4 x 4 3-4 inches in size, made of seal grain , real sealor Russia leather, in a thoro

Memindex dimensions mentioned in a 1904 advertisement<br /> cards: 2 3/4 x 4 1/2 inches<br /> case: 2 3/4 x 4 3/4 inches

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

In this manuscript, Wang et al. assess the role of wall shear stress and hydrostatic pressure during valve morphogenesis at stages where the valve elongates and takes shape. The authors elegantly demonstrate that shear and pressure have different effects on cell proliferation by modulating YAP signaling. The authors use a combination of in vitro and in vivo approaches to show that YAP signaling is activated by hydrostatic pressure changes and inhibited by wall shear stress.

There are a few elements that would require clarification:

1) The impact of YAP on valve stiffness was unclear to me. How is YAP signaling affecting stiffness? is it through cell proliferation changes? I was unclear about the model put forward:<br /> - Is it cell proliferation (cell proliferation fluidity tissue while non-proliferating tissue is stiffer?)<br /> - Is it through differential gene expression?<br /> This needs clarification.

2) The model proposes an early asymmetric growth of the cushion leading to different shear forces (oscillatory vs unidirectional shear stress). What triggers the initial asymmetry of the cushion shape? is YAP involved?

3) The differential expression of YAP and its correlation to cell proliferation is a little hard to see in the data presented. Drawings highlighting the main areas would help the reader to visualise the results better.

4) The origin of osmotic/hydrostatic pressure in vivo. While shear is clearly dependent upon blood flow, it is less clear that hydrostatic pressure is solely dependent upon blood flow. For example, it has been proposed that ECM accumulation such as hyaluronic acid could modify osmotic pressure (see for example Vignes et al.PMID: 35245444). Could the authors clarify the following questions:<br /> - How blood flow affects osmotic pressure in vivo?<br /> - Is ECM a factor that could affect osmotic pressure in this system?

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

Farahani et al. developed a novel biosensor, pYtag, to monitor receptor tyrosine kinase activity using live cell fluorescence microscopy. The approach to the sensor design relies on adding a tyrosine activation motif to a receptor tyrosine kinase of interest which when phosphorylated recruits a fluorescently-tagged SH2 domain protein. The sensor was used to monitor EGFR and ErbB2 activity and characterize their activity in the presence of different ligands, allowing for the kinetics of receptor activity to be determined in live cells with high temporal resolution.

The design, characterization, and verification of the sensor with controls were rigorously done and the sensor appears to be a good approach to monitoring receptor tyrosine kinases. In addition to this, the biological characterization of RTK signaling kinetics allowed for mathematical modeling to determine the dimerization affinity of ligand-bound receptors is the rate-limiting step of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling dynamics. Proving these sensors can be used to monitor biological activities in live cells.

Initial proof of principles of pYtag was demonstrated in cell lines where the tags were expressed, the authors went beyond this and showed the tagging system could be gene edited to endogenous proteins allowing for the function of receptor tyrosine kinase to be measured under physiological concentrations.

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

Over the past decade, Cryo-EM analysis of assembling ribosomes has mapped the major intermediates of the pathway. Our understanding of the mechanisms by which ATPases drive the transitions between states has been slower to develop because of the transient nature of these events. Here, the authors use cryo-EM and biochemical and molecular genetic approaches to examine the function of the DEAD-box ATPase Spb4 and the AAA-ATPase Rea1 in RNP remodeling. Spb4 works on the pre-60S in an early nucleolar state. The authors find that Spb4 acts to remodel the three-way junction of H62/H63/H63a at the base of expansion segment ES27. Interestingly, Spb4 appears to interact stably with a folding intermediate in the ADP rather than ATP-bound form. This work represents one of the few cases in which an RNA helicase of ribosome biogenesis has been captured and engaged with its substrate. The authors then show that the addition of the AAA-ATPase Rea1 to Spb4-purified particles results in the release of Ytm1, a known target of Rea1. However, they did not observe an efficient release of Ytm1 when particles were affinity purified via Ytm1, suggesting that the recruitment of Spb4 is important for this step. Cryo-EM analysis of Spb4-particles treated with Rea1 revealed the previously characterized state NE particles but no additional intermediates. Consequently, this analysis of Rea1 is less informative about its function than is their work on Spb4 helicase activity. In general, the data support the authors' conclusions and the data are well presented.

Major points<br /> 1. The Erzberger group has recently published work regarding the function of Spb4. They similarly found that Spb4 is necessary for remodeling the 3-way junction at the base of ES27. Although it was posted to Biorxiv in Feb 2022, it was not formally published until Dec 2022. The authors should cite this work and include a brief discussion comparing conclusions.<br /> 2. L311. The heading "Coupled pre-60S dissociation of the Ytm1-Erb1 complex and RNA helicase Has1" should be changed. Coupling implies a mechanistic interplay. Although the release of Ytm1 and Has1 both depend on Rea1, the data do not support the conclusion of mechanistic coupling. In fact, the authors write in lines 328-329 "Thus, the Rea1-dependent pre-60S release of the Ytm1-Erb1 complex occurs before and independently of Has1..." Independently cannot also imply coupling.<br /> 3. L339-342 Combining data sets for uniform processing was a great idea! This approach should be used more often in cryo-EM analyses of in vitro maturation reactions.<br /> 4. L428 The authors need to amend their comment that this is the first structure of Spb4-bound to the substrate as this has recently been published by the Erzberger group and was first posted as a preprint in early 2022.

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

The function of the nervous system relies on precisely connected neuronal networks. A previous study from the Luo lab reported an important pair of molecular interaction between an adhesion GPCR, latrophilin-2, and teneurin-3 in specifying the connections between CA1 neurons in the hippocampus and the subiculum. This new study continues to investigate the signaling mechanisms, particularly whether the trimeric G proteins are involved. Adhesion GPCRs are in general still under studied, esp in nervous system. This study also used a clever misexpression approach, which provide signaling studies in the in vivo context. The data are of high quality and convincing.

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

In this manuscript, the authors address the mechanism of concentration of HIV-1 particles following interaction with Siglec-1 and define important differences in this process between immature DCs and mature DCs. The methods are largely derived from imaging that is followed by quantitation of nanoclustering of Siglec-1, distance from the center of the cell, and the effects of inhibitors of actin and RhoA pathways. The quantitative imaging approach is a strength and appears quite carefully done. Another strength is the new findings regarding the role of the formin-dependent actin cytoskeletal rearrangements and RhoA activation on clustering and polarization leading to the formation of the virus-containing compartment (VCC). The results are convincing that mature DCs demonstrate more nanoclustering and that formins and RhoA are important in the clustering that occurs of viruses or virus-like particles following capture by Siglec-1. This information should be valuable to the field.

The weaknesses are not in the methods and major conclusions themselves, but there are a number of aspects of the study that could be strengthened. The definition of a VCC here is simply a spot of Siglec-1 that has coalesced with VLPs. A more complete study would include typical VCC markers such as CD81, CD9, and others and would extend the findings to prove that the mechanism invoked actually elicits VCC formation, as opposed to clustering of Siglec-1 and VLPs along the surface of the cell. This study does not establish the mechanism of membrane invagination or tubule formation that occurs with VCC formation, so perhaps it is really describing the initial, surface-related steps of VCC formation but not subsequent internalization events required to form the deeper, vacuole-like VCC.

Nevertheless, this study provides new insights into the initial steps of VCC formation and is provocative regarding how this can be achieved by Siglec-1 in the absence of the need for a cytoplasmic tail. The formin-dependence of VCC formation will be of interest in future studies of HIV uptake and trans-infection events mediated by dendritic cells and macrophages. Some of the findings can be directly translated to the biological context of how VCCs form in HIV-infected macrophages. These will all likely be of substantial interest to those working on HIV and other viruses that are captured by Siglec-1.

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

The authors perform an elegant study where they show that intravitreal injection of human monocytes from patients with AMD cause reduced ERG B-wave amplitudes and photoceptor cell loss compared to controls in the photic retinal injury model. Differentiation of human monocytes from patients with AMD into M2a macrophages caused increased photoreceptor cell loss compared to M1 macrophages. Next, the authors show that after co-culturing retinal explants with M1 and M2a human macrophages followed by TUNEL staining, M2 human macrophages had significantly more apoptotic photoreceptor cells than M1 human macrophages. The authors show that human M2a macrophages have significantly more ROS compared to M0 and M1 human macrophages; however, injection of human M2a macrophages did not cause increased oxidative damage compared to control conditions. Using a multiplex cytokine assay of 120 cytokines between human M1 and M2a macrophages-conditioned medium, the authors found increased levels of 9 cytokines, including three HCC-1, MCP-4, and MPIF-1, which are ligands of the C-C chemokine receptor CCR1. Co-staining showed CCR1 expression in Muller cells following photic injury. In the rd10 mouse model of retinal degeneration as well as aged BALB/c mice CCR1 is upregulated in Muller cells. Injection of mice with the CCR1-specific inhibitor BX471 caused increased photoreceptor numbers and B-wave amplitudes in the photic-injury model. Overall the experiments are well performed and of interest to the field.

-

-

www.ebay.com www.ebay.com

-

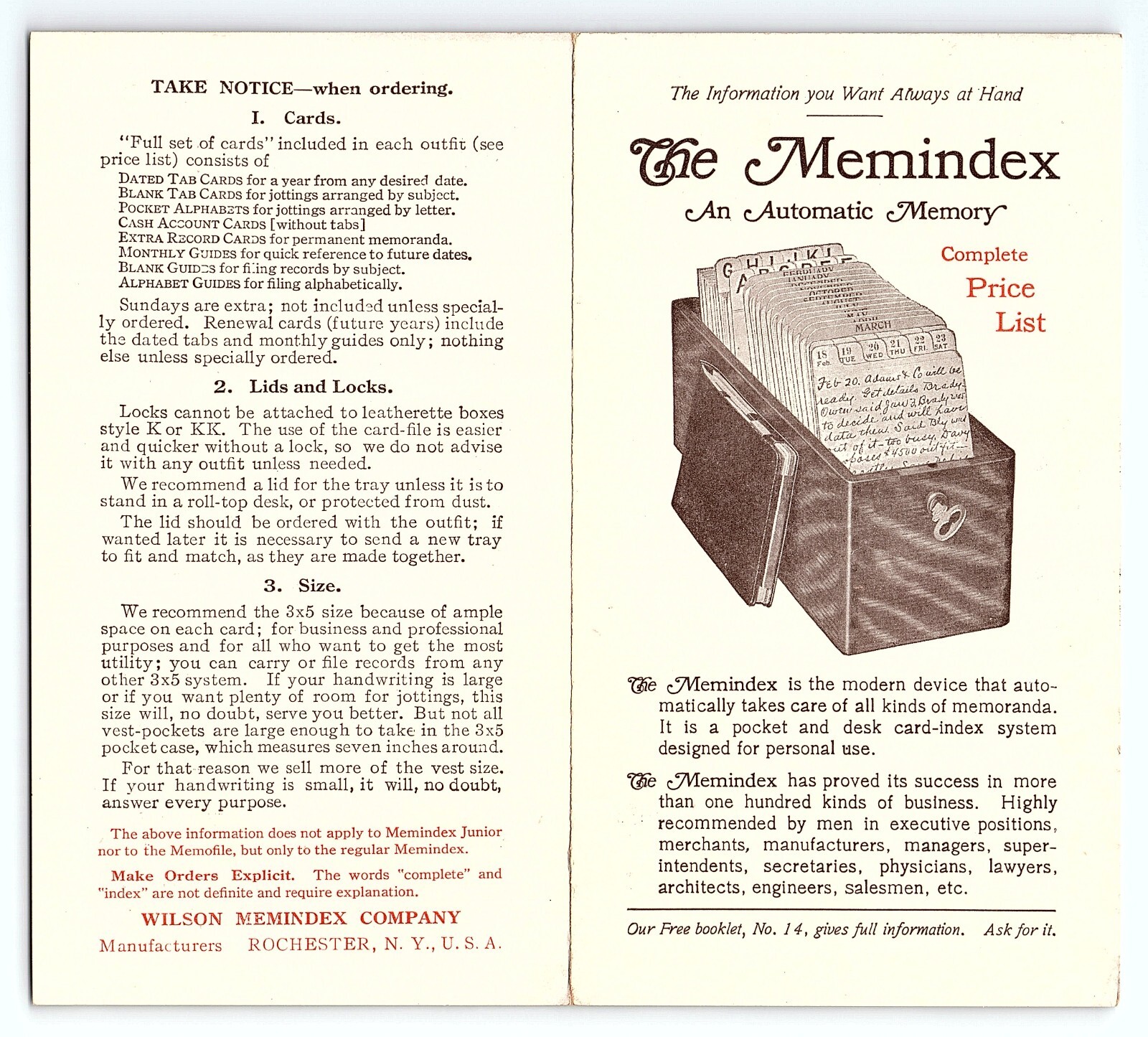

1930s Wilson Memindex Co Index Card Organizer Pre Rolodex Ad Price List Brochure

archived page: https://web.archive.org/web/20230310010450/https://www.ebay.com/itm/165910049390

Includes price lists

List of cards includes: - Dated tab cards for a year from any desired. - Blank tab cards for jottings arranged by subject. - These were sold in 1/2 or 1/3 cut formats - Pocket Alphabets for jottings arranged by letter. - Cash Account Cards [without tabs]. - Extra Record Cards for permanent memoranda. - Monthly Guides for quick reference to future dates. - Blank Guides for filing records by subject.. - Alphabet Guides for filing alphabetically.

Memindex sales brochures recommended the 3 x 5" cards (which had apparently been standardized by 1930 compared to the 5 1/2" width from earlier versions around 1906) because they could be used with other 3 x 5" index card systems.

In the 1930s Wilson Memindex Company sold more of their vest pocket sized 2 1/4 x 4 1/2" systems than 3 x 5" systems.

Some of the difference between the vest sized and regular sized systems choice was based on the size of the particular user's handwriting. It was recommended that those with larger handwriting use the larger cards.

By the 1930's at least the Memindex tag line "An Automatic Memory" was being used, which also gave an indication of the ubiquity of automatization of industrialized life.

The Memindex has proved its success in more than one hundred kinds of business. Highly recommended by men in executive positions, merchants, manufacturers, managers, .... etc.

Notice the gendering of users specifically as men here.

Features: - Sunday cards were sold separately and by my reading were full length tabs rather than 1/6 tabs like the other six days of the week - Lids were custom fit to the bases and needed to be ordered together - The Memindex Jr. held 400 cards versus the larger 9 inch standard trays which had space for 800 cards and block (presumably a block to hold them up or at an angle when partially empty).

The Memindex Jr., according to a price sheet in the 1930s, was used "extensively as an advertising gift".

The Memindex system had cards available in bundles of 100 that were labeled with the heading "Things to Keep in Sight".

-

-

-

312 Oak Midget Tray WWeesCoverEquipped same as]No.324,price.55CTohold cards14x3.No.423.Equippedasabove,tohold65Ccards 24x4, priceNo. 533. Standard size.to hold card 3x5, equip-ped as above,price..........No. 7- Nickel ....PrepaidinU. S.onreceiptofpriceNo. 324OakMidgetTraytheCoverWeis75cNo. 644. To hold cards4x6,equipped$1.10(StyleNos.312,423.533and644)asabove......(Style No. 324,213.335and446.)Send for catalog showing many other time-saving office devices. Our goods are soldyour dealer does not carry our line we can supply you direct from the factory.To hold cards 24x4. lengthof tray2%in..equippedwithAtoZindexand100record cards 45cNo. 213. To hold cards 14x3in,, lenght of tray 24in..equipped asabove40cNo.335.Standardsize,tohold3x5 cards.equipped asabove50c80cNo. 446. To hold 4x6 cards,equipped asabove.Any of these trays sent pre-paid in U. S. on receipt ofpriceby stationers everywhere. IfNo. 6 Union St.The WeisManufacturing Co.,Monroe,Mich.,U. S.A.Please mention SYSTEM when writing to advertisers

Notice the 1 1/4" x 3" cards, 2 1/4 x 4" cards in addition to the 3 x 5" and 4 x 6".

-

-

www.biorxiv.org www.biorxiv.org

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):