Thy purpose marriage, send me word to-morrow,

Juliet sets the condition: his love must aim at marriage. She's practical.

Thy purpose marriage, send me word to-morrow,

Juliet sets the condition: his love must aim at marriage. She's practical.

the more I give to thee, 985The more I have,

Paradox: Love isn't lessened by giving; it grows. Central romantic idea.

My bounty is as boundless as the sea,

Simile: Her capacity to love is infinite. A beautiful paradox follows.

Romeo. The exchange of thy love's faithful vow for mine.

Plot: Romeo wants a formal commitment from her.

Too like the lightning,

Simile: Their love is as sudden and brief as lightning. She fears it will vanish.

Which is the god of my idolatry,

Metaphor: She worships Romeo. He is her religion now.

Juliet. O, swear not by the moon, the inconstant moon,

Symbolism: Juliet rejects the changing moon as a symbol for vows. She wants constancy.

Thou mayst prove false; at lovers' perjuries Then say, Jove laughs.

Allusion: Old saying: the god Jupiter laughs at lovers' broken vows, so they don't matter.

Juliet. Thou know'st the mask of night is on my face,

Metaphor: Darkness hides her blush, giving her courage to speak frankly.

Two of the fairest stars in all the heaven, 860Having some business, do entreat her eyes To twinkle in their spheres till they return. What if her eyes were there, they in her head?

Hyperbole: Her eyes are so bright stars swap places with them. Extreme romantic exaggeration.

Her vestal livery is but sick and green

Symbolism: The pale green of virginity is sickly. He urges her to "cast it off."

and kill the envious moon,

Mythology: The moon is Diana, goddess of chastity. Romeo wants Juliet to reject virginity.

Juliet is the sun.

Metaphor: First of many light images. She brings light and life to his world.

Romeo. He jests at scars that never felt a wound.

Metaphor: Romeo says Mercutio jokes about love's pain because he's never felt it (the "wound").

Mercutio. If love be blind, love cannot hit the mark.

Sexual Joke: If love is blind, it can't hit the target (sexual innuendo).

Mercutio. If love be blind, love cannot hit the mark.

Proverb: Love is blind. Benvolio says Romeo's irrational love fits the dark.

To be consorted with the humorous night:

Personification: Night is moody ("humorous"). Romeo is hiding in its moods.

The ape is dead, and I must conjure him. 815I conjure thee by Rosaline's bright eyes, By her high forehead and her scarlet lip, By her fine foot, straight leg and quivering thigh And the demesnes that there adjacent lie,

Sexual Innuendo: Mercutio lists her physical features suggestively, mocking Romeo's past lust

Speak to my gossip Venus one fair word,

Informal Language: "Gossip" means friend. Mercutio talks casually about the love goddess.

Mercutio. Nay, I'll conjure too. 805Romeo! humours! madman! passion! lover! Appear thou in the likeness of a sigh: Speak but one rhyme, and I am satisfied; Cry but 'Ay me!' pronounce but 'love' and 'dove;' Speak to my gossip Venus one fair word, 810One nick-name for her purblind son and heir, Young Adam Cupid, he that shot so trim, When King Cophetua loved the beggar-maid! He heareth not, he stirreth not, he moveth not; The ape is dead, and I must conjure him. 815I conjure thee by Rosaline's bright eyes, By her high forehead and her scarlet lip, By her fine foot, straight leg and quivering thigh And the demesnes that there adjacent lie, That in thy likeness thou appear to us!

Mockery: Mercutio humorously calls for Romeo using love clichés and Rosaline's body parts. Shows he doesn't understand true love.

Romeo. Can I go forward when my heart is here? Turn back, dull earth, and find thy centre out.

Metaphor: His heart (Juliet) is with the Capulets, so he can't leave. Shows total devotion.

Google search is collapsing. Between 2021 and 2025, websites experienced traffic losses exceeding 60% from organic search, with quality content creators punished while AI-generated spam flourished. Confirmed algorithm updates decreased from 10 annually in 2021-2022 to just 4 in 2025, yet volatility reached record-breaking levels.

Google search 'collapsing' . When do we hit the point it is no longer fit for purpose?

The State of Search (Why This Guide is Needed) Before we dive into resources, we need to talk about why human curation matters more than ever.

Human curation key element in finding the others. Vgl triangulation, [[Social software werkt in driehoeken 20060506070412]]

Follow-up post by Brennan Kenneth Brown after a previous one urging people to their own web sites. The response was large, but w many questions on how to discover more, and 'find the others'

Conference on open search, in the context of digital sovereignty. #2026/10/05 to #2026/10/07 (tentative), hybrid, open to general interested public. Location:: Berlin

Curious as to what their angle on digital sovereignty wrt search will be/is.

iBestuur says X is on the path to being banned in the EU bc of Grok. Making and distributing CSAM and AI created explicit images of people are all criminal offences across the EU, next to not being compliant with GDPR, DSA and soon AI reg. A similar app has been shutdown in Italy on GDPR grounds.

Antagonistic bots can also be used as a form of political pushback that may be ethically justifiable.

This sentence is quite interesting because it indicates that antagonistic robots are not always completely harmful. In some cases, these accounts can be used to reveal social inequality and prompt institutions to take responsibility. This also makes the ethical issues of robots more complicated, as the same technology may either be used for deception or, in specific intentions and situations, to promote social justice.

Bots might have significant limits on how helpful they are, such as tech support bots you might have had frustrating experiences with on various websites.

This shows how bots may not always be effective, especially in more specific contexts such as tech support. I have had frustrating experiences with bots like these, and it shows the limits of the current programming of the bots.

Antagonistic bots can also be used as a form of political pushback that may be ethically justifiable. For example, the “Gender Pay Gap Bot” bot on Twitter is connected to a database on gender pay gaps for companies in the UK. Then on International Women’s Day, the bot automatically finds when any of those companies make an official tweet celebrating International Women’s Day and it quote tweets it with the pay gap at that company:

It is "confrontational", but it has a social justice purpose - to use automation to counter the "pseudo-equality propaganda" of corporate marketing and bring the real structural problem (the wage gap) to the public. This example shows that some antagonistic bots can instead become tools for monitoring power.

Bots might have significant limits on how helpful they are, such as tech support bots you might have had frustrating experiences with on various websites. 3.2.2. Antagonistic bots:# On the other hand, some bots are made with the intention of harming, countering, or deceiving others.

The "bot" itself is not good or bad, but depends on what it is designed for and how the rules of the platform constrain it. For example, friendly bots (automatic captioning, vaccine progress, red panda images) essentially improve the efficiency of information acquisition and enhance the user experience; antagonistic bots (spam, fake fans, astroturfing), however, can create false public opinion and make people think that "many people support/oppose a certain opinion", which directly affects public judgment

We also would like to point out that there are fake bots as well, that is real people pretending their work is the result of a Bot. For example, TikTok user Curt Skelton posted a video claiming that he was actually an AI-generated / deepfake character:

As someone who's majoring in a creative field, I find it both incredibly interesting and concerning just how advanced AI is getting, and where this rapid innovation will take us in just a few years. It's so jarring to be watching a video on Tiktok or Instagram and fully believe it to be completely real, just to feel the need to dissect the video to see if it's really real. I can't begin to imagine how the job industry will change due to AI, but with innovation there (hopefully) comes opportunity.**

On the other hand, some bots are made with the intention of harming, countering, or deceiving others. For example, people use bots to spam advertisements at people. You can use bots as a way of buying fake followers, or making fake crowds that appear to support a cause (called Astroturfing).

Although bot programs are written by one or more people, the individuals who decide the content and deploy the posts often have clear intentions. While responsibility may partially lie with those who develop the bots, the primary accountability for harmful consequences should rest with those who create and control the content.

3.2.3. Corrupted bots# As a final example, we wanted to tell you about Microsoft Tay a bot that got corrupted. In 2016, Microsft launched a Twitter bot that was intended to learn to speak from other Twitter users and have conversations. Twitter users quickly started tweeting racist comments at Tay, which Tay learned from and started tweeting out within one day. Read more about what went wrong from Vice How to Make a Bot That Isn’t Racist 3.2.4. Registered vs. Unregistered bots# Most social media platforms provide an official way to connect a bot to their platform (called an Application Programming Interface, or API). This lets the social media platform track these registered bots and provide certain capabilities and limits to the bots (like a rate limit on how often the bot can post). But when some people want to get around these limits, they can make bots that don’t use this official API, but instead, open the website or app and then have a program perform clicks and scrolls the way a human might. These are much harder for social media platforms to track, and they normally ban accounts doing this if they are able to figure out that is what is happening. 3.2.5. Fake Bots# We also would like to point out that there are fake bots as well, that is real people pretending their work is the result of a Bot. For example, TikTok user Curt Skelton posted a video claiming that he was actually an AI-generated / deepfake character:

This passage uses three levels to remind us that "robots" themselves do not equate to intelligence or objectivity. Tay's "contamination" illustrates that machine learning-based conversational robots absorb biases from the platform as "language norms"—when training data comes from an environment full of provocation and racism, the system becomes an amplifier of prejudice; the problem is not just a technical failure, but a governance failure of treating a "public platform" as a safe training ground. Next, the "registered vs. unregistered bots" reveal the cat-and-mouse game of platform regulation and countermeasures: API restrictions act as rules and guardrails, while simulated clicks bypassing APIs disguise automation as "human," making it harder for platforms to track, demonstrating that visibility and controllability are themselves forms of power. Finally, the "fake bots" point to another form of deception: humans pretending to be AI to gain traffic, a sense of mystery, or immunity from responsibility—this blurs the line of "authenticity" and reminds us that in the attention economy, technological identity can also be used for performance and marketing.

On the other hand, some bots are made with the intention of harming, countering, or deceiving others. For example, people use bots to spam advertisements at people. You can use bots as a way of buying fake followers, or making fake crowds that appear to support a cause (called Astroturfing). As one example, in 2016, Rian Johnson, who was in the middle of directing Star Wars: The Last Jedi, got bombarded by tweets that all originated in Russia (likely making at least some use of bots). “I’ve gotten a rush of tweets – coordinated tweets. Like, somewhere else on the internet there’s like a group on the internet saying, ‘Okay, everyone tweet Rian Johnson.’ All from Russian accounts, and all begging me not to kill Admiral Hux in this movie.” From: https://www.imdb.com/video/vi3962091545 (start at 7:49) After the Star Wars: Last Jedi was released, there was a significant online backlash. When a researcher looked into it: [Morten] Bay found that 50.9% of people tweeting negatively about “The Last Jedi” were “politically motivated or not even human,” with a number of these users appearing to be Russian trolls. The overall backlash against the film wasn’t even that great, with only 21.9% of tweets analyzed about the movie being negative in the first place. https://www.indiewire.com/2018/10/star-wars-last-jedi-backlash-study-russian-trolls-rian-johnson-1202008645/ Antagonistic bots can also be used as a form of political pushback that may be ethically justifiable. For example, the “Gender Pay Gap Bot” bot on Twitter is connected to a database on gender pay gaps for companies in the UK. Then on International Women’s Day, the bot automatically finds when any of those companies make an official tweet celebrating International Women’s Day and it quote tweets it with the pay gap at that company:

This passage shifts the discussion of "bots" from neutral tools back into the context of power and manipulation: they can not only automate the dissemination of information but also automate the creation of "false impressions of public opinion" (follower boosting, astroturfing) and targeted harassment (the coordinated attack on Rian Johnson). More notably, the research mentions that a large number of negative tweets were "politically motivated or non-human," meaning that the anger, ridicule, and boycotts we see online may not be a natural aggregation of "genuine public opinion," but rather an emotional landscape that is organized, amplified, and fabricated. Finally, the "Gender Pay Gap Bot" provides a counterexample: this "adversarial" automation can be used for public accountability—by forcibly juxtaposing corporate holiday statements with structural data (wage gaps), it forces people to see the reality obscured by public relations language. The key is not whether "bots are good or bad," but who uses them and whose perceptions and interests they are used to shape.

As a final example, we wanted to tell you about Microsoft Tay a bot that got corrupted. In 2016, Microsft launched a Twitter bot that was intended to learn to speak from other Twitter users and have conversations. Twitter users quickly started tweeting racist comments at Tay, which Tay learned from and started tweeting out within one day. Read more about what went wrong from Vice How to Make a Bot That Isn’t Racist

The discussion of bots influencing public opinion raises important ethical questions about power and accountability. Even if a bot spreads accurate information, the scale and speed of automation can still distort public discourse. This suggests that ethical evaluation of bots should consider not only content accuracy but also their impact on human decision-making and democratic processes.

The discussion of bots influencing public opinion raises important ethical questions about power and accountability. Even if a bot spreads accurate information, the scale and speed of automation can still distort public discourse. This suggests that ethical evaluation of bots should consider not only content accuracy but also their impact on human decision-making and democratic processes.

ethically justifiable

To me I find it problematic in practice for there to be a distinction between ethical and non-ethical use of antagonistic bots. Everybody has their own worldview and values. To define some of these values as ethical on social media is to impose them on everyone. Maybe this would be okay if there was a democratic way for this. But there isn't. These bots are made to "get a rise out of people" or stir emotions. Subjecting people to that through automated bots under the guise of ethics I disagree with

We also would like to point out that there are fake bots as well, that is real people pretending their work is the result of a Bot. For example, TikTok user Curt Skelton posted a video claiming that he was actually an AI-generated / deepfake character:

Today, we are exposed to a growing number of AI-generated videos on platforms like Instagram and YouTube. While some are clearly AI, others appear highly realistic, often prompting viewers to question whether the content was created by a human or AI. This ongoing uncertainty has begun to shape a habitual way of thinking, where we instinctively evaluate the authenticity of what we see. As AI and bots become further integrated into digital media, this shift raises important questions about how trust, perception, and credibility may evolve in the future.

Bots, on the other hand, will do actions through social media accounts and can appear to be like any other user.

This sentence is very important because it emphasizes that bot accounts can blend in with real users on social media. When robots look like real people, it becomes more difficult for people to judge whether what they see is real and trustworthy. This has also raised ethical issues regarding transparency and how platforms should label or regulate accounts.

Note that sometimes people use “bots” to mean inauthentically run accounts, such as those run by actual humans, but are paid to post things like advertisements or political content. We will not consider those to be bots, since they aren’t run by a computer. Though we might consider these to be run by “human computers” who are following the instructions given to them, such as in a click farm:

This paragraph, I mean, it's very important that people know what bots do, they misconceptualize them, but in this day of ChatGPT, Microsoft Copilot, Google Gemini, DuckAI. These bots though are actually interesting in a sense how that not all accounts called ‘bots’ are truly automated. I think this distinction is important because it changes how we understand online content, whether it’s influenced by algorithms or by campaigns.

He made you for a highway to my bed; But I, a maid, die maiden-widowed. Come, cords, come, nurse; I'll to my wedding-bed; 1860And death, not Romeo, take my maidenhead!

Symbolism: The ropes were for their wedding night. Now they’re useless.

Shame come to Romeo!

Nurse’s betrayal: The Nurse curses Romeo, upsetting Juliet.

Nurse. I saw the wound, I saw it with mine eyes,— God save the mark!—here on his manly breast: 1775A piteous corse, a bloody piteous corse; Pale, pale as ashes, all bedaub'd in blood, All in gore-blood; I swounded at the sight.

Imagery: Graphic description of Tybalt’s body. Adds to the horror.

This torture should be roar'd in dismal hell. Hath Romeo slain himself? say thou but 'I,' And that bare vowel 'I' shall poison more Than the death-darting eye of cockatrice: I am not I, if there be such an I; 1770Or those eyes shut, that make thee answer 'I.' If he be slain, say 'I'; or if not, no: Brief sounds determine of my weal or woe.

Juliet thinks Romeo killed himself. She’s frantic and heartbroken.

Not yet enjoy'd: so tedious is this day As is the night before some festival To an impatient child that hath new robes

Simile: Waiting for Romeo is like a child waiting to wear new clothes. Shows her youth.

Juliet. Gallop apace, you fiery-footed steeds, Towards Phoebus' lodging: such a wagoner 1720As Phaethon would whip you to the west, And bring in cloudy night immediately.

Juliet can’t wait for night so Romeo can come. She’s passionate and eager.

Benvolio. Tybalt, here slain, whom Romeo's hand did slay; Romeo that spoke him fair, bade him bethink 1670How nice the quarrel was, and urged withal Your high displeasure: all this uttered With gentle breath, calm look, knees humbly bow'd, Could not take truce with the unruly spleen Of Tybalt deaf to peace, but that he tilts 1675With piercing steel at bold Mercutio's breast, Who all as hot, turns deadly point to point, And, with a martial scorn, with one hand beats Cold death aside, and with the other sends It back to Tybalt, whose dexterity, 1680Retorts it: Romeo he cries aloud, 'Hold, friends! friends, part!' and, swifter than his tongue, His agile arm beats down their fatal points, And 'twixt them rushes; underneath whose arm 1685An envious thrust from Tybalt hit the life Of stout Mercutio, and then Tybalt fled; But by and by comes back to Romeo, Who had but newly entertain'd revenge, And to 't they go like lightning, for, ere I 1690Could draw to part them, was stout Tybalt slain. And, as he fell, did Romeo turn and fly. This is the truth, or let Benvolio die.

Plot: Benvolio tells the truth about the fight, defending Romeo.

Benvolio. O noble prince, I can discover all The unlucky manage of this fatal brawl: 1660There lies the man, slain by young Romeo, That slew thy kinsman, brave Mercutio.

Plot: Benvolio tells the truth about the fight, defending Romeo.

Benvolio. O Romeo, Romeo, brave Mercutio's dead!

Plot: Confirmation of death. The turning point of the play.

Romeo. This gentleman, the prince's near ally, My very friend, hath got his mortal hurt In my behalf; my reputation stain'd With Tybalt's slander,—Tybalt, that an hour Hath been my kinsman! O sweet Juliet, 1620Thy beauty hath made me effeminate And in my temper soften'd valour's steel!

Romeo feels responsible and thinks love made him weak (“effeminate”).

rogue, a villain, that fights by the book of arithmetic! Why the devil came you between us? I was hurt under your arm.

Tragedy: Mercutio says Romeo got in the way. This guilt will haunt Romeo.

[TYBALT under ROMEO's arm stabs MERCUTIO, and flies with his followers] Mercutio. I am hurt.

Plot: The fatal moment. Romeo’s interference accidentally gets Mercutio killed.

Mercutio. Good king of cats, nothing but one of your nine lives; that I mean to make bold withal, and as you shall use me hereafter, drybeat the rest of the eight. Will you pluck your sword out of his pitcher by the ears? make haste, lest mine be about your 1580ears ere it be out.

Mercutio calls Tybalt “king of cats” (mockery) and challenges him to fight.

Romeo. Tybalt, the reason that I have to love thee 1560Doth much excuse the appertaining rage To such a greeting: villain am I none; Therefore farewell; I see thou know'st me not.

Plot: Romeo secretly loves Tybalt now (he’s family through Juliet). He refuses to fight.

Mercutio. By my heel, I care not.

Mercutio is defiant and doesn’t fear the Capulets. He’s confident and unafraid.

Mercutio. Nay, an there were two such, we should have none shortly, for one would kill the other. Thou! why, thou wilt quarrel with a man that hath a hair more, 1515or a hair less, in his beard, than thou hast: thou wilt quarrel with a man for cracking nuts, having no other reason but because thou hast hazel eyes: what eye but such an eye would spy out such a quarrel? Thy head is as fun of quarrels as an egg is full of 1520meat, and yet thy head hath been beaten as addle as an egg for quarrelling: thou hast quarrelled with a man for coughing in the street, because he hath wakened thy dog that hath lain asleep in the sun: didst thou not fall out with a tailor for wearing 1525his new doublet before Easter? with another, for tying his new shoes with old riband? and yet thou wilt tutor me from quarrelling!

Mercutio’s exaggeration. Hyperbole: Mercutio claims Benvolio would fight over anything, even a cough or someone’s shoes. This is funny exaggeration.

Mercutio. Thou art like one of those fellows that when he enters the confines of a tavern claps me his sword upon the table and says 'God send me no need of 1505thee!' and by the operation of the second cup draws it on the drawer, when indeed there is no need. Benvolio. Am I like such a fellow? Mercutio. Come, come, thou art as hot a Jack in thy mood as any in Italy, and as soon moved to be moody, and as 1510soon moody to be moved.

Mercutio mocks Benvolio. Mercutio jokes that Benvolio is quick to fight. He’s teasing, showing his playful, sarcastic side.

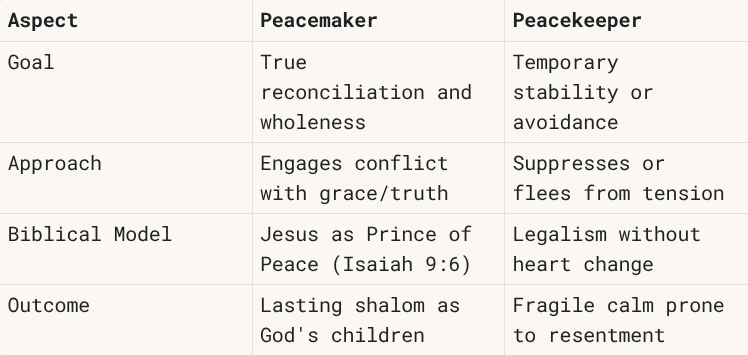

Benvolio. I pray thee, good Mercutio, let's retire: The day is hot, the Capulets abroad, 1500And, if we meet, we shall not scape a brawl; For now, these hot days, is the mad blood stirring.

Benvolio is the peacekeeper. He wants to avoid a fight because it's hot and people are angry (“mad blood stirring”).

early signals the new Dutch cabinet will have a minister for digital affairs.

het regime

National newspaper now using 'regime' to describe the cabinet level behaviour

Die aspecten van het trumpisme – wetteloosheid, vijanddenken, leugens, omdraaiingen en geweld – zijn de pijlers van zowel zijn binnenlandse als buitenlandse beleid. Dat is al tien jaar het geval,

The aspects of trumpism, lawlessness, thinking in terms of enemies, lies, Orwellian spinning, violence, are the pillars of domestic and foreign policy.

Editorial opinion in Dutch national newspaper "The naive belief everything will turn out fine in the USA must end"

Shopify Integration

Shopify isnt live in the US yet

the autopoiesis of the IndyWeb

x

eLife Assessment

This manuscript proposes a lateralized, lobe-specific brain-liver sympathetic neurocircuit regulating hepatic glucose metabolism and presents anatomical evidence for sympathetic crossover at the porta hepatis using viral tracing and neuromodulation approaches. While the topic is of important significance and the methodologies are, in principle, state-of-the-art, significant concerns regarding experimental design, incomplete methodological reporting, sparse and ambiguous labeling, and overi-nterpretation of the data substantially weaken support for the study's central conclusions, thereby limiting the study's completeness. The work will be of interest to biologists, clinicians, and physiologists.

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

This manuscript by Wang et al. reports the potential involvement of an asymmetric neurocircuit in the sympathetic control of liver glucose metabolism.

Strengths:

The concept that the contralateral brain-liver neurocircuit preferentially regulates each liver lobe may be interesting.

Weaknesses:

However, the experimental evidence presented did not support the study's central conclusion.

(1) Pseudorabies virus (PRV) tracing experiment:<br /> The liver not only possesses sympathetic innervations but also vagal sensory innervations. The experimental setup failed to distinguish whether the PRV-labeling of LPGi (Lateral Paragigantocellular Nucleus) is derived from sympathetic or vagal sensory inputs to the liver.

(2) Impact on pancreas:<br /> The celiac ganglia not only provide sympathetic innervations to the liver but also to the pancreas, the central endocrine organ for glucose metabolism. The chemogenetic manipulation of LPGi failed to consider a direct impact on the secretion of insulin and glucagon from the pancreas.

(3) Neuroanatomy of the brain-liver neurocircuit:<br /> The current study and its conclusion are based on a speculative brain-liver sympathetic circuit without the necessary anatomical information downstream of LPGi.

(4) Local manipulation of the celiac ganglia:<br /> The left and right ganglia of mice are not separate from each other but rather anatomically connected. The claim that the local injection of AAV in the left or right ganglion without affecting the other side is against this basic anatomical feature.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

The manuscript by Wang and colleagues aims to determine whether the left and right LPGi differentially regulate hepatic glucose metabolism and to reveal decussation of hepatic sympathetic nerves.

The authors used tissue clearing to identify sympathetic fibers in the liver lobes, then injected PRV into the hepatic lobes. Five days post-injection, PRV-labeled neurons in the LPGi were identified. The results indicated contralateral dominance of premotor neurons and partial innervation of more than one lobe. Then the authors activated each side of the LPGi, resulting in a greater increase in blood glucose levels after right-sided activation than after left-sided activation, as well as changes in protein expression in the liver lobes. These data suggested modulation of HGP (hepatic glucose production) in a lobe-specific manner. Chemical denervation of a particular lobe did not affect glucose levels due to compensation by the other lobes. In addition, nerve bundles decussate in the hepatic portal region.

Strengths:

The manuscript is timely and relevant. It is important to understand the sympathetic regulation of the liver and the contribution of each lobe to hepatic glucose production. The authors use state-of-the-art methodology.

Weaknesses:

(1) The wording/terminology used in the manuscript is misleading, and it is not used in the proper context. For instance, the goal of the study is "to investigate whether cerebral hemispheres differentially regulate hepatic glucose metabolism..." (see abstract); however, the authors focus on the brainstem (a single structure without hemispheres). Similarly, symmetric is not the best word for the projections.

(2) Sparse labeling of liver-related neurons was shown in the LPGi (Figure 1). It would be ideal to have lower magnification images to show the area. Higher quality images would be necessary, as it is difficult to identify brainstem areas. The low number of labeled neurons in the LPGi after five days of inoculation is surprising. Previous findings showed extensive labeling in the ventral brainstem at four days post-inoculation (Desmoulins et al., 2025). Unfortunately, it is not possible to compare the injection paradigm/methods because the PRV inoculation is missing from the methods section. If the PRV is different from the previously published viral tracers, time-dependent studies to determine the order of neurons and the time course of infection would be necessary.

(3) Not all LPGi cells are liver-related. Was the entire LPGi population stimulated, or was it done in a cell-type-specific manner? What was the strain, sex, and age of the mice? What was the rationale for using the particular viral constructs?

(4) The authors should consider the effect of stimulation of double-labeled neurons (innervating more than one lobe) and potential confounding effects regarding other physiological functions.

(5) The authors state that "central projections directly descend along the sympathetic chain to the celiac-superior mesenteric ganglia". What they mean is unclear. Do the authors refer to pre-ganglionic neurons or premotor neurons? How does it fit with the previous literature?

(6) How was the chemical denervation completed for the individual lobes?

(7) The Western Blot images look like they are from different blots, but there are no details provided regarding protein amount (loading) or housekeeping. What was the reason to switch beta-actin and alpha-tubulin? In Figures 3F -G, the GS expression is not a good representative image. Were chemiluminescence or fluorescence antibodies used? Were the membranes reused?

(8) Key references using PRV for liver innervation studies are missing (Stanley et al, 2010 [PMID: 20351287]; Torres et al., 2021 [PMID: 34231420]; Desmoulins et al., 2025 [PMID: 39647176]).

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

Summary:

This study found a lobe-specific, lateralized control of hepatic glucose metabolism by the brain and provides anatomical evidence for sympathetic crossover at the porta hepatis. The findings are particularly insightful to the researchers in the field of liver metabolism, regeneration, and tumors.

Strengths:

Increasing evidence suggests spatial heterogeneity of the liver across many aspects of metabolism and regenerative capacity. The current study has provided interesting findings: neuronal innervation of the liver also shows anatomical differences across lobes. The findings could be particularly useful for understanding liver pathophysiology and treatment, such as metabolic interventions or transplantation.

Weaknesses:

Inclusion of detailed method and Discussion:

(1) The quantitative results of PRV-labeled neurons are presented, and please include the specific quantitative methods.

(2) The Discussion can be expanded to include potential biological advantages of this complex lateralized innervation pattern.

Reviewer #4 (Public review):

Summary:

The studies here are highly informative in terms of anatomical tracing and sympathetic nerve function in the liver related to glucose levels, but given that they are performed in a single species, it is challenging to translated them to humans, or to determine whether these neural circuits are evolutionarily conserved. Dual-labeling anatomical studies are elegant, and the addition of chemogenetic and optogenetic studies is mechanistically informative. Denervation studies lack appropriate controls, and the role of sensory innervation in the liver is overlooked.

Specific Weaknesses - Major:

(1) The species name should be included in the title.

(2) Tyrosine hydroxylase was used to mark sympathetic fibers in the liver, but this marker also hits a portion of sensory fibers that need to be ruled out in whole-mount imaging data

(3) Chemogenetic and optogenetic data demonstrating hyperglycemia should be described in the context of prior work demonstrating liver nerve involvement in these processes. There is only a brief mention in the Discussion currently, but comparing methods and observations would be helpful.

(4) Sympathetic denervation with 6-OHDA can drive compensatory increases to tissue sensory innervation, and this should be measured in the liver denervation studies to implicate potential crosstalk, especially given the increase in LPGi cFOS that may be due to afferent nerve activity. Compensatory sympathetic drive may not be the only culprit, though it is clearly assumed to be. The sensory or parasympathetic/vagal innervation of the liver is altogether ignored in this paper and could be better described in general.

Author response:

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

This manuscript by Wang et al. reports the potential involvement of an asymmetric neurocircuit in the sympathetic control of liver glucose metabolism.

Strengths:

The concept that the contralateral brain-liver neurocircuit preferentially regulates each liver lobe may be interesting.

Weaknesses:

However, the experimental evidence presented did not support the study's central conclusion.

We sincerely thank the reviewer for recognizing the conceptual novelty of our work and for constructive comments aimed at enhancing its rigor and clarity. In response, we will carry out targeted experiments to address the points raised, including: (i) further characterization of LPGi projections to vagal and sympathetic circuits; (ii) evaluation of potential pancreatic involvement; and (ii) validation of the specificity of chemogenetic activation within the proposed circuit. We anticipate completing the revised version within 8 weeks.

(1) Pseudorabies virus (PRV) tracing experiment:

The liver not only possesses sympathetic innervations but also vagal sensory innervations. The experimental setup failed to distinguish whether the PRV-labeling of LPGi (Lateral Paragigantocellular Nucleus) is derived from sympathetic or vagal sensory inputs to the liver.

Thank you for raising this important point. We fully agree that the liver receives both sympathetic and vagal sensory innervation, and we acknowledge that PRV-based tracing alone does not definitively distinguish between these two pathways. This represents a limitation of the original experimental design.

Based on established anatomical literature as well as our experimental observations, vagal sensory neuron cell bodies reside in the nodose ganglion (NG), and their central projections terminate predominantly in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) (Nature. 2023;623(7986):387-396; Curr Biol. 2020;30(20):3986-3998.e5.), which is located in the dorsomedial medulla. In contrast, the LPGi, together with other sympathetic-related nuclei, is predominantly distributed in the ventral medulla (Cell Metab. 2025;37(11):2264-2279.e10; Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):5079.).

To directly assess the contribution of vagal sensory pathways, we will perform an additional PRV tracing experiment using two groups of mice: one with bilateral nodose ganglion (NG) removal and a sham-operated control group. Identical PRV injections will be delivered to the liver in both groups, and PRV labeling in the LPGi will be quantitatively compared. Preservation of LPGi labeling following NG ablation would indicate that PRV transmission occurs primarily via sympathetic, rather than vagal sensory, pathways. These data will be incorporated into the revised manuscript and are expected to be completed within 3 weeks.

(2) Impact on pancreas:

The celiac ganglia not only provide sympathetic innervations to the liver but also to the pancreas, the central endocrine organ for glucose metabolism. The chemogenetic manipulation of LPGi failed to consider a direct impact on the secretion of insulin and glucagon from the pancreas.

Thank you for this important comment. We agree that the celiac ganglia (CG) provide sympathetic innervation not only to the liver but also to the pancreas, which plays a central role in glucose homeostasis through the secretion of both insulin and glucagon. Therefore, the potential pancreatic implications associated with LPGi chemogenetic manipulation worth careful consideration.

To address this concern, we examined circulating glucagon levels following chemogenetic manipulation of the LPGi. As shown in the Supplementary Figure below, plasma glucagon (GCG) concentrations were not significantly altered at 30, 60, 90, or 120 minutes compared with control mice (n = 6), indicating that LPGi manipulation does not measurably affect glucagon secretion under our experimental conditions.

We acknowledge that insulin secretion was not assessed in the study, which represents an important limitation given the pancreatic innervation of the CG. To further strengthen our interpretation, we are performing additional experiments in newly prepared mice to measure circulating insulin levels following LPGi manipulation. These data together with Author response image 1 below will be included in the revised manuscript upon completion.

Author response image 1.

Plasma concentrations of GCG in mice following LPGi GABAergic neurons activation.

(3) Neuroanatomy of the brain-liver neurocircuit:<br /> The current study and its conclusion are based on a speculative brain-liver sympathetic circuit without the necessary anatomical information downstream of LPGi.

Thank you for raising this important point. A clear anatomical definition of the downstream pathways linking the brain to the liver is essential for interpreting the proposed brain-liver sympathetic circuit.

However, the present study (Figure 4A) provides direct anatomical evidence supporting the organization of the brain–liver sympathetic neurocircuit. These observations are consistent with our recent detailed characterization of the brain-liver sympathetic circuit published in Cell Metabolism (Cell Metab. 2025;37(11):2264–2279), LPGi GABAergic neurons inhibit GABAergic neurons in the caudal ventrolateral medulla (CVLM). Disinhibition of CVLM reduces GABAergic suppression of rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) neurons, which are key excitatory drivers of sympathetic tone. RVLM neurons project to sympathetic preganglionic neurons in the sympathetic chain (Syc). These neurons synapse with postganglionic sympathetic neurons in ganglia such as the celiac-superior mesenteric ganglion (CG-SMG). Postganglionic sympathetic fibers then innervate the liver, releasing NE to activate hepatic β<sub>2</sub>-adrenergic receptors and stimulate HGP.

Together, these data establish a coherent anatomical basis for the proposed brain-liver sympathetic pathway and clarify the downstream organization relevant to the functional experiments presented here.

Author response image 2.

Tracing scheme (Left) and whole-mount imaging (Right) of PRV-labeled brain-liver neurocircuit. Scale bars, 3,000 (whole mount) or 1,000 (optical sections) μm.

(4) Local manipulation of the celiac ganglia:<br /> The left and right ganglia of mice are not separate from each other but rather anatomically connected. The claim that the local injection of AAV in the left or right ganglion without affecting the other side is against this basic anatomical feature.

Thank you for raising this important anatomical point. We fully acknowledge that the left and right celiac ganglia (CG) in mice are interconnected, and that unilateral viral injection could theoretically affect the contralateral side. The celiac–superior mesenteric ganglion (CG-SMG) complex serves as a major sympathetic hub that regulates visceral organ functions. Recent transcriptomic, anatomical, and functional studies have revealed that the CG-SMG is not a homogeneous structure but is composed of molecularly and functionally distinct neuronal populations. These populations exhibit specialized projection patterns and regulate different aspects of gastrointestinal physiology, supporting a model of modular sympathetic control. (Nature. 2025 Jan;637(8047):895-902). Therefore, we were aware of this phenomenon during the initial stages of these experiments.

To minimize unintended spread to the contralateral CG, we took two complementary approaches.

First, we optimized the injection strategy by using an extremely small injection volume (100 nL per site), with a very slow infusion rate (50 nL/min), and fine glass micropipettes. With these refinements, contralateral viral spread was rarely observed.

Second, and importantly, all animals included in the final analyses were subjected to post hoc anatomical verification. After completion of the experiments, CG were collected, sectioned, and examined for viral expression. As shown in Supplementary Figure 5F, only mice in which viral expression was strictly confined to the targeted CG, with no detectable infection in the contralateral ganglion, were included in the presented data.

Together, these measures ensure that the reported effects are attributable to local manipulation of the intended CG. We will ensure that the Methods section more explicitly details these technical precautions and that the legend for Figure S5F clearly states its role in validating injection specificity.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

The manuscript by Wang and colleagues aims to determine whether the left and right LPGi differentially regulate hepatic glucose metabolism and to reveal decussation of hepatic sympathetic nerves.

The authors used tissue clearing to identify sympathetic fibers in the liver lobes, then injected PRV into the hepatic lobes. Five days post-injection, PRV-labeled neurons in the LPGi were identified. The results indicated contralateral dominance of premotor neurons and partial innervation of more than one lobe. Then the authors activated each side of the LPGi, resulting in a greater increase in blood glucose levels after right-sided activation than after left-sided activation, as well as changes in protein expression in the liver lobes. These data suggested modulation of HGP (hepatic glucose production) in a lobe-specific manner. Chemical denervation of a particular lobe did not affect glucose levels due to compensation by the other lobes. In addition, nerve bundles decussate in the hepatic portal region.

We thank the reviewer for the thorough and constructive evaluation of our manuscript. In direct response, we will undertake comprehensive revisions to enhance the rigor and clarity of the study, including: (i) correcting ambiguous or misleading terminology pertaining to anatomical resolution and sympathetic circuit organization; (ii) expanding the Methods section with complete experimental details, improved image presentation, and explicit justification of our viral and genetic approaches; and (iii) strengthening data interpretation by addressing issues related to sparse PRV labeling, projection heterogeneity, and the functional implications of double-labeled neurons. All revisions are expected to be completed within 8 weeks.

Strengths:

The manuscript is timely and relevant. It is important to understand the sympathetic regulation of the liver and the contribution of each lobe to hepatic glucose production. The authors use state-of-the-art methodology.

Weaknesses:

(1) The wording/terminology used in the manuscript is misleading, and it is not used in the proper context. For instance, the goal of the study is "to investigate whether cerebral hemispheres differentially regulate hepatic glucose metabolism..." (see abstract); however, the authors focus on the brainstem (a single structure without hemispheres). Similarly, symmetric is not the best word for the projections.

We thank the reviewer for raising these critical points regarding terminology and conceptual framing. We acknowledge that certain phrases in our original manuscript may have been overly broad or ambiguous, particularly in describing the scope of sympathetic heterogeneity and the specificity of neural projections. Due to practical constraints and the scope of our study, our investigation is focused on the brainstem, which represents the final common pathway for these lateralized commands. We acknowledge that terms referring to the cerebral hemispheres do not accurately describe our study.

We are revising the manuscript to ensure accurate and consistent terminology and will submit the revised version with these corrections.

(2) Sparse labeling of liver-related neurons was shown in the LPGi (Figure 1). It would be ideal to have lower magnification images to show the area. Higher quality images would be necessary, as it is difficult to identify brainstem areas. The low number of labeled neurons in the LPGi after five days of inoculation is surprising. Previous findings showed extensive labeling in the ventral brainstem at four days post-inoculation (Desmoulins et al., 2025). Unfortunately, it is not possible to compare the injection paradigm/methods because the PRV inoculation is missing from the methods section. If the PRV is different from the previously published viral tracers, time-dependent studies to determine the order of neurons and the time course of infection would be necessary.

We sincerely thank the reviewer for these detailed and constructive comments regarding the PRV tracing experiments. We fully agree that careful presentation and interpretation of the anatomical data are essential for ensuring rigor and transparency. We address each point in detail below.

(1) Image magnification and anatomical context of LPGi labeling

We agree that the original images did not sufficiently convey the broader anatomical context of the LPGi. In the revised manuscript, we will replace the original panels in Figure 1 with new images that include lower-magnification overviews of the brainstem, alongside higher-magnification views of the LPGi. These images clearly delineate the LPGi with respect to established anatomical landmarks and atlas boundaries. Image contrast and resolution will also be optimized to allow unambiguous identification of PRV-labeled neurons and surrounding structures.

(2) Sparse LPGi labeling at 5 days post-injection and methodological details

We apologize for the omission of the detailed PRV injection protocol in the original Methods section. We deliberately used small-volume, focal injections (1 µL per liver lobe) to minimize viral spread and to restrict labeling to circuits specifically connected to the targeted hepatic region. Under these conditions, early-stage or intermediate-order upstream nuclei such as the LPGi are expected to exhibit relatively sparse labeling compared to more proximal autonomic nuclei. This information will add, including the PRV strain, viral titer, injection volume, precise injection coordinates, and surgical procedures.

(3) Not all LPGi cells are liver-related. Was the entire LPGi population stimulated, or was it done in a cell-type-specific manner? What was the strain, sex, and age of the mice? What was the rationale for using the particular viral constructs?

We thank the reviewer for this insightful and important question. We agree that not all neurons within the LPGi are liver-related, and we apologize that our rationale was not clearly articulated in the original manuscript.

(1) Our decision to target GABAergic neurons in the LPGi using Gad1-Cre mice was based on prior experimental evidence rather than an assumption about the entire LPGi population. In our previous study (Cell Metab. 2025;37(11):2264-2279.e10), we performed single-cell RNA sequencing on retrogradely labeled LPGi neurons following liver tracing. These analyses revealed that the majority of liver-projecting LPGi neurons are GABAergic in nature. Based on these findings, we chose to selectively manipulate GABAergic neurons in the LPGi rather than the entire LPGi neuronal population, in order to achieve greater cellular specificity and to minimize potential confounding effects arising from heterogeneous neuron types within this region. We regret that this rationale was not clearly described in the original submission and have now revised the manuscript to explicitly state this reasoning.

(2) In addition, we apologize for the omission of mouse strain, sex, and age information in the Methods section. These details will be fully added.

(3) We selected AAV-based viral vectors, specifically the AAV9 serotype, due to their well-established efficiency in transducing neurons in the brainstem, relatively low toxicity, and widespread use in circuit-level chemogenetic and optogenetic studies. When combined with Cre-dependent viral constructs in Gad1-Cre mice, this approach enabled selective and reliable manipulation of LPGi GABAergic neurons.

(4) The authors should consider the effect of stimulation of double-labeled neurons (innervating more than one lobe) and potential confounding effects regarding other physiological functions.

We thank the reviewer for raising this important point. We agree that neurons innervating more than one liver lobe could, in principle, introduce potential confounding effects and may reflect higher-order integrative autonomic neurons.

This consideration is consistent with a key finding of the cited study: the celiac-superior mesenteric ganglion (CG-SMG) contains molecularly distinct sympathetic neuron populations (e.g., RXFP1<sup>+</sup> vs. SHOX2<sup>+</sup>) that exhibit complementary organ projections and separate, non‑overlapping functions. Specifically, RXFP1<sup>+</sup> neurons innervate secretory organs (pancreas, bile duct) to regulate secretion, while SHOX2<sup>+</sup> neurons innervate the gastrointestinal tract to control motility. This functional segregation supports the concept of specialized autonomic modules rather than a uniform,“fight or flight”response, reinforcing the need for careful interpretation of circuit-specific manipulations. (Nature. 2025;637(8047):895-902; Neuron. Published online December 10, 2025).

In our PRV tracing experiments, the proportion of double-labeled neurons was relatively small, suggesting that the majority of labeled LPGi neurons preferentially associate with individual hepatic lobes. Nevertheless, we recognize that activation of this minority population could contribute to broader physiological effects beyond strictly lobe-specific regulation. We acknowledge that the absence of single-cell-level resolution in the current study limits our ability to further dissect the functional heterogeneity of these projection-defined neurons, and we will explicitly state this as a limitation in the revised manuscript. We will explicitly acknowledge this possibility in the revised manuscript and included it as a limitation of the current study. We thank the reviewer for highlighting this important conceptual consideration.

(5) The authors state that "central projections directly descend along the sympathetic chain to the celiac-superior mesenteric ganglia". What they mean is unclear. Do the authors refer to pre-ganglionic neurons or premotor neurons? How does it fit with the previous literature?

We thank the reviewer for pointing out this imprecise wording. We agree that the original phrasing was anatomically inaccurate and potentially confusing. The pathways we intended to describe involve brainstem premotor neurons that project to sympathetic preganglionic neurons in the spinal cord. These preganglionic neurons then innervate neurons in the celiac–superior mesenteric ganglia, which in turn provide postganglionic input to the liver.

We are revising the manuscript to clearly distinguish premotor from preganglionic neurons and to describe this pathway in a manner consistent with the established organization of sympathetic autonomic circuits reported in the previous literature. The revised wording will explicitly reflect this hierarchical relay structure.

(6) How was the chemical denervation completed for the individual lobes?

We thank the reviewer for raising this important methodological concern. We agree that potential diffusion of 6-OHDA is a critical issue when performing lobe-specific chemical denervation, and we apologize that our original description did not sufficiently clarify how this was controlled.

In the revised Methods section, we will provide a detailed description of the denervation procedure, including the injection volume and concentration of 6-OHDA, as well as the physical separation and isolation of individual hepatic lobes during application to minimize diffusion to adjacent tissue.

To directly assess the specificity of the chemical denervation, we included immunofluorescence and Western blot analyses demonstrating a selective reduction of sympathetic markers in the targeted lobe, with minimal effects on non-targeted lobes. These results support the effectiveness and relative spatial confinement of the 6-OHDA treatment under our experimental conditions.

We thank the reviewer for highlighting this point, which has helped us improve both the clarity and rigor of the manuscript.

(7) The Western Blot images look like they are from different blots, but there are no details provided regarding protein amount (loading) or housekeeping. What was the reason to switch beta-actin and alpha-tubulin? In Figures 3F -G, the GS expression is not a good representative image. Were chemiluminescence or fluorescence antibodies used? Were the membranes reused?

We thank the reviewer for this careful and detailed evaluation of the Western blot data. We apologize that insufficient methodological detail was provided in the original submission.

(1) We would like to clarify that the protein bands shown within each panel were derived from the same membrane. To improve transparency, we will provide full, uncropped images of the corresponding membranes in the supplementary materials. In addition, detailed information regarding protein loading amounts, gel conditions, and housekeeping controls will be added to the Methods section.

(2) The use of different loading controls (β-actin or α-tubulin) reflects a technical consideration rather than an experimental inconsistency. In our experiments, the molecular weight of the TH (62kDa) was too close to α-tubulin (55kDa), and β-actin (42kDa) was therefore used to avoid band overlap and to ensure accurate quantification.

(3) Regarding the GS signal shown in Figures 3F–G, we agree that the original representative image was suboptimal. This appears to be related to antibody performance rather than sample quality. To address this, we are repeating the GS Western blot using a newly validated antibody. The original tissue samples had been aliquoted and stored at −80 °C, allowing reliable re-analysis. This work will be done in 8 weeks.

(4) All Western blot experiments were detected using chemiluminescence, and membrane stripping and reprobing procedures are now explicitly described in the Methods section.

We thank the reviewer for highlighting these issues, which significantly improve the rigor and clarity of our data presentation.

(8) Key references using PRV for liver innervation studies are missing (Stanley et al, 2010 [PMID: 20351287]; Torres et al., 2021 [PMID: 34231420]; Desmoulins et al., 2025 [PMID: 39647176]).

We thank the reviewer for pointing out these important and highly relevant references that were inadvertently omitted in our initial submission. The studies by Stanley et al. (Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2010), Torres et al. (Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol, 2021), and Desmoulins et al. (Auton Neurosci, 2025) represent key PRV-based retrograde tracing work that has mapped central neural circuits innervating the liver and thus provide essential context for our anatomical analyses.

We agree that inclusion of these studies is necessary to properly situate our findings within the existing literature. Accordingly, we will incorporate citations to these references in the revised manuscript and discuss their relationship to our results.

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

Summary:

This study found a lobe-specific, lateralized control of hepatic glucose metabolism by the brain and provides anatomical evidence for sympathetic crossover at the porta hepatis. The findings are particularly insightful to the researchers in the field of liver metabolism, regeneration, and tumors.

Strengths:

Increasing evidence suggests spatial heterogeneity of the liver across many aspects of metabolism and regenerative capacity. The current study has provided interesting findings: neuronal innervation of the liver also shows anatomical differences across lobes. The findings could be particularly useful for understanding liver pathophysiology and treatment, such as metabolic interventions or transplantation.

Weaknesses:

Inclusion of detailed method and Discussion:

We sincerely thank the reviewer for the positive and constructive feedback, which will significantly enhance both the methodological rigor and the broader biological interpretation of our study. In direct response, we will revise the Discussion to elaborate on the potential physiological advantages of a lateralized and lobe-specific pattern of liver innervation. Furthermore, we will expand the Methods section to include a comprehensive description of the quantitative analysis applied to PRV-labeled neurons. Together, these revisions will strengthen the manuscript’s clarity, depth, and relevance to researchers in hepatic metabolism, regeneration, and disease. We expect to complete all updates within 8 weeks.

(1) The quantitative results of PRV-labeled neurons are presented, and please include the specific quantitative methods.

We thank the reviewer for this helpful suggestion. We will add a detailed description of the quantitative methods used to analyze PRV-labeled neurons in the revised Methods section. This includes information on the counting criteria, the brain regions analyzed, how the regions of interest were delineated, and the normalization procedures applied to obtain the reported neuron counts.

(2) The Discussion can be expanded to include potential biological advantages of this complex lateralized innervation pattern.

We appreciate the reviewer’s suggestion. We will expand the Discussion to include a paragraph addressing the potential biological significance of lateralized liver innervation. We highlight that this asymmetric organization could allow for more precise, lobe-specific regulation of hepatic metabolism, enable integration of distinct physiological signals, and potentially provide robustness against perturbations. These points will discuss in the revised manuscript.

Reviewer #4 (Public review):

Summary:

The studies here are highly informative in terms of anatomical tracing and sympathetic nerve function in the liver related to glucose levels, but given that they are performed in a single species, it is challenging to translated them to humans, or to determine whether these neural circuits are evolutionarily conserved. Dual-labeling anatomical studies are elegant, and the addition of chemogenetic and optogenetic studies is mechanistically informative. Denervation studies lack appropriate controls, and the role of sensory innervation in the liver is overlooked.

We sincerely appreciate the reviewer's thoughtful evaluation and fully agree that findings derived from a single-species model must be interpreted with caution in relation to human physiology. In direct response, we will revise the manuscript to explicitly clarify that all experimental data were obtained in mice and to provide a discussion of the limitations regarding direct extrapolation to humans. Concurrently, we will expand the Discussion section by integrating our findings with recent human and translational studies, including a multicenter clinical trial demonstrating that catheter-based endovascular denervation of the celiac and hepatic arteries significantly improved glycemic control in patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes, without major adverse events (Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2025;10(1):371). While our current work focuses on defining the anatomical organization and functional asymmetry of this circuit in mice, the clinical findings suggest that the core principles, sympathetic control of hepatic glucose metabolism via CG-liver pathways, may be conserved and of translational relevance. Additionally, we will clarify the interpretation of tyrosine hydroxylase labeling and expand the discussion of hepatic sensory and parasympathetic innervation, acknowledging their important roles in liver–brain communication and identifying them as key directions for future research. Collectively, these revisions will provide a more balanced, clinically informed, and rigorous framework for interpreting our findings, and we aim to complete all updates within 8 weeks.

Specific Weaknesses - Major:

(1) The species name should be included in the title.

We thank the reviewer for this suggestion. We agree that the species should be clearly indicated. The findings presented in this study were obtained in mice using tissue clearing and whole-organ imaging approaches. Due to technical limitations, these observations are currently limited to the mouse strain. We will update the title and clarified the species used throughout the manuscript.

(2) Tyrosine hydroxylase was used to mark sympathetic fibers in the liver, but this marker also hits a portion of sensory fibers that need to be ruled out in whole-mount imaging data

We thank the reviewer for pointing this out. We acknowledge that tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) labels not only sympathetic fibers but also a subset of sensory fibers. We will add a limitation of this point in the revised manuscript. In addition, ongoing experiments using retrograde PRV labeling from the liver, combined with sectioning, are being used to distinguish sympathetic fibers from vagal and dorsal root ganglion–derived sensory fibers. These data will be included in a forthcoming update of the manuscript and are expected to be completed in approximately 6 weeks.

(3) Chemogenetic and optogenetic data demonstrating hyperglycemia should be described in the context of prior work demonstrating liver nerve involvement in these processes. There is only a brief mention in the Discussion currently, but comparing methods and observations would be helpful.

We thank the reviewer for this suggestion. Previous studies largely relied on electrical stimulation to modulate liver innervation, which provides relatively coarse control of neural activity (Eur J Biochem. 1992;207(2):399-411). By contrast, our use of chemogenetic and optogenetic approaches allows selective, cell-type–specific manipulation of LPGi neurons. We will revise the Discussion to place our functional data in the context of prior work, highlighting how these more precise approaches improve understanding of the contribution of liver-innervating neurons to hyperglycemia.

(4) Sympathetic denervation with 6-OHDA can drive compensatory increases to tissue sensory innervation, and this should be measured in the liver denervation studies to implicate potential crosstalk, especially given the increase in LPGi cFOS that may be due to afferent nerve activity. Compensatory sympathetic drive may not be the only culprit, though it is clearly assumed to be. The sensory or parasympathetic/vagal innervation of the liver is altogether ignored in this paper and could be better described in general.

We thank the reviewer for this insightful comment and agree that chemical sympathetic denervation with 6-OHDA may induce compensatory changes in non-sympathetic hepatic inputs, including sensory and parasympathetic (vagal) innervation. As the reviewer correctly points out, increased LPGi cFOS activity may reflect afferent nerve engagement rather than solely compensatory sympathetic drive.

More broadly, we agree that the central nervous system functions as an integrated homeostatic network that continuously processes diverse afferent signals, including hepatic sensory and vagal inputs, as well as other interoceptive cues. From this perspective, the LPGi cFOS changes observed in our study likely represent one component of a complex integrative response rather than evidence for a single dominant pathway.

We acknowledge that the present study did not directly assess hepatic sensory or parasympathetic innervation, which represents a limitation in scope. In the revised manuscript, we will expand the Discussion to explicitly note this limitation and provide a more balanced consideration of potential crosstalk among sympathetic, sensory, and parasympathetic pathways in shaping LPGi activity following hepatic denervation.

Recommendations for the authors:

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations for the authors):

Although the findings are interesting, this reviewer has major concerns about the experimental design, methodology, results, and interpretation of the data. Experimental details are lacking, including basic information (age, sex, strain of mice, procedures, magnification, etc.).

We thank the reviewer for this important recommendation. We agree that comprehensive reporting of experimental details is essential for rigor and reproducibility.

In the revised manuscript, we will add complete information regarding mouse strain, sex, age, and sample size for each experiment. In addition, detailed descriptions of surgical procedures, viral constructs, injection parameters, imaging magnification, and analysis methods have been incorporated into the Methods section.

These revisions ensure that all experiments are described with sufficient technical detail and clarity to allow accurate interpretation and replication of our findings.

Reviewer #3 (Recommendations for the authors):

Addressing a few questions might help:

(1) The study found that liver-associated LPGi neurons are predominantly GABAergic. It would be informative to molecularly characterize the PRV-traced, liver-projecting LPGi neurons to determine their neurochemical phenotypes.

We thank the reviewer for this insightful suggestion. We agree that molecular characterization of liver-projecting LPGi neurons is important for understanding their functional identity.

This issue has been addressed in detail in our recent study (Cell Metab. 2025;37(11):2264-2279.e10), in which we performed single-cell RNA sequencing on retrogradely traced LPGi neurons connected to the liver. These analyses demonstrated that the majority of liver-projecting LPGi neurons are GABAergic, with a defined transcriptional profile distinct from neighboring non–liver-related populations.

Based on these findings, the current study selectively targets GABAergic LPGi neurons using Gad1-Cre mice. We are now explicitly referencing and summarizing these molecular results in the revised manuscript to clarify the neurochemical identity of the PRV-traced LPGi neurons.

(2) Is it possible to do a local microinjection of a sodium channel blocker (e.g., lidocaine) or an adrenergic receptor antagonist into the porta hepatis? That would potentially provide additional evidence for the porta hepatis as the functional crossover point.

We appreciate the reviewer’s thoughtful suggestion. While pharmacological blockade at the porta hepatis could modulate local neural activity, the proposed approach may not fully capture the distinction between ipsilateral and contralateral inputs, and may not conclusively establish neural crossover at this particular site.

In our view, the anatomical evidence provided by whole-mount tissue clearing, dual-labeled tracing, and direct visualization of decussating nerve bundles at the porta hepatis offers a more definitive demonstration of sympathetic crossover. Pharmacological blockade would affect both crossed and uncrossed fibers simultaneously and therefore would not specifically resolve the anatomical organization of this decussation.

Nevertheless, we agree that functional interrogation of the porta hepatis represents an interesting direction for future work, and we will now acknowledge this possibility in the Discussion.

(3) It is possible to investigate the effects of unilateral LPGi manipulation or ablation of one side of CG/SMG on liver metabolism, such as hyperglycemia?

We thank the reviewer for this important suggestion. We agree that unilateral ablation or silencing of the CG-SMG could provide additional insight into lateralized sympathetic control of liver metabolism.

However, precise and selective ablation of one side of the CG-SMG through 6-OHDA without affecting the contralateral ganglion or adjacent autonomic structures remains technically challenging, particularly given the anatomical connectivity between the two sides. We are currently optimizing approaches to achieve reliable unilateral manipulation.

If successful within the revision timeframe, we will include these experiments and corresponding metabolic analyses in the revised manuscript. If not, we will explicitly discuss this experimental limitation and the predicted metabolic consequences of unilateral CG-SMG ablation as an important direction for future studies. This work will be done in 6 weeks.

Reviewer #4 (Recommendations for the authors):

In the abstract and elsewhere, the use of the term 'sympathetic release' is unclear - do you mean release of nerve products, such as the neurotransmitter norepinephrine? This should be more clearly defined.

We thank the reviewer for pointing out this ambiguity. We agree that the term “sympathetic release” was imprecise. In the revised manuscript, we will explicitly refer to the release of sympathetic neurotransmitters, primarily norepinephrine, from postganglionic sympathetic fibers.

We will revise the wording throughout the manuscript to ensure accurate and consistent terminology and to avoid potential confusion regarding the underlying neurobiological mechanisms.

eLife Assessment

The findings are important, as they identify MIRO1 as a central regulator linking mitochondrial positioning and respiratory chain function to VSMC proliferation, neointima formation, and human vasoproliferative disease. Overall, the strength of evidence is convincing, with comprehensive in vivo and in vitro data, including human cells and added bioenergetic analyses, that broadly support the main claims despite some remaining limitations in mechanistic and mitochondrial assays.

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

In this paper, the authors investigate the effects of Miro1 on VSMC biology after injury. Using conditional knockout animals, they provide the important observation that Miro1 is required for neointima formation. They also confirm that Miro1 is expressed in human coronary arteries. Specifically, in conditions of coronary diseases, it is localized in both media and neointima and, in atherosclerotic plaque, Miro1 is expressed in proliferating cells.

However, the role of Miro1 in VSMC in CV diseases is poorly studied and the data available are limited; therefore, the authors decided to deepen this aspect. The evidence that Miro-/- VSMCs show impaired proliferation and an arrest in S phase is solid and further sustained by restoring Miro1 to control levels, normalizing proliferation. Miro1 also affects mitochondrial distribution, which is strikingly changed after Miro1 deletion. Both effects are associated with impaired energy metabolism due to the ability of Miro1 to participate in MICOS/MIB complex assembly, influencing mitochondrial cristae folding. Interestingly, the authors also show the interaction of Miro1 with NDUFA9, globally affecting super complex 2 assembly and complex I activity.<br /> Finally, these important findings also apply to human cells and can be partially replicated using a pharmacological approach, proposing Miro1 as a target for vasoproliferative diseases.

Strengths:

The discovery of Miro1 relevance in neointima information is compelling, as well as the evidence in VSMC that MIRO1 loss impairs mitochondrial cristae formation, expanding observations previously obtained in embryonic fibroblasts.<br /> The identification of MIRO1 interaction with NDUFA9 is novel and adds value to this paper. Similarly, the findings that VSMC proliferation requires mitochondrial ATP support the new idea that these cells do not rely mostly on glycolysis.

The revised manuscript includes additional data supporting mitochondrial bioenergetic impairment in MIRO1 knockout VSMCs. Measurements of oxygen consumption rate (OCR), along with Complex I (ETC-CI) and Complex V activity, have been added and analyzed across multiple experimental conditions. Collectively, these findings provide a more comprehensive characterization of the mitochondrial functional state. Following revision, the association between MIRO1 deficiency and impaired Complex I activity is more robust.

Although the precise molecular mechanism of action remains to be fully elucidated, in this updated version, experiments using a MIRO1 reducing agent are presented with improved clarity

Although some limitations remain, the authors have addressed nearly all the concerns raised, and the manuscript has substantially improved

Weaknesses:

Figure 6: The authors do not address the concern regarding the cristae shape; however, characterization of the cristae phenotype with MIRO1 ΔTM would have strengthened the mechanistic link between MIRO1 and the MIB/MICOS complex

Although the authors clarified their reasoning, they did not explore in vivo validation of key biochemical findings, which represents a limitation of the current study. While their justification is acknowledged, at least a preliminary exploratory effort could have been evaluated to reinforce the translational relevance of the study.

Finally, in line with the explanations outlined in the rebuttal, the Discussion section should mention the limits of MIRO1 reducer treatment.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

This study identifies the outer‑mitochondrial GTPase MIRO1 as a central regulator of vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) proliferation and neointima formation after carotid injury in vivo and PDGF-stimulation ex vivo. Using smooth muscle-specific knockout male mice, complementary in vitro murine and human VSMC cell models, and analyses of mitochondrial positioning, cristae architecture and respirometry, the authors provide solid evidence that MIRO1 couples mitochondrial motility with ATP production to meet the energetic demands of the G1/S cell cycle transition. However, a component of the metabolic analyses are suboptimal and would benefit from more robust methodologies. The work is valuable because it links mitochondrial dynamics to vascular remodelling and suggests MIRO1 as a therapeutic target for vasoproliferative diseases, although whether pharmacological targeting of MIRO1 in vivo can effectively reduce neointima after carotid injury has not been explored. This paper will be of interest to those working on VSMCs and mitochondrial biology.

Strengths:

The strength of the study lies in its comprehensive approach assessing the role of MIRO1 in VSMC proliferation in vivo, ex vivo and importantly in human cells. The subject provides mechanistic links between MIRO1-mediated regulation of mitochondrial mobility and optimal respiratory chain function to cell cycle progression and proliferation. Finally, the findings are potentially clinically relevant given the presence of MIRO1 in human atherosclerotic plaques and the available small molecule MIRO1.

Weaknesses:

(1) High-resolution respirometry (Oroboros) to determine mitochondrial ETC activity in permeabilized VSMCs would be informative.

(2) Therapeutic targeting of MIRO1 failed to prevent neointima formation, however, the technical difficulties of such an experiment is appreciated.

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

Summary:

This study addresses the role of MIRO1 in vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation, proposing a link between MIRO1 loss and altered growth due to disrupted mitochondrial dynamics and function. While the findings are useful for understanding the importance of mitochondrial positioning and function in this specific cell type, the main bioenergetic and mechanistic claims are not strongly supported.

Strengths:

This study focuses on an important regulatory protein, MIRO1, and its role in vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) proliferation, a relatively underexplored context.

This study explores the link between smooth muscle cell growth, mitochondrial dynamics, and bioenergetics, which is a significant area for both basic and translational biology.

The use of both in vivo and in vitro systems provides a useful experimental framework to interrogate MIRO1 function in this context.

Weaknesses: