AAV8-hSyn-DIO-hM3D(Gq)-mCherry

DOI: 10.1038/s41593-025-02078-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_44361

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_44361

AAV8-hSyn-DIO-hM3D(Gq)-mCherry

DOI: 10.1038/s41593-025-02078-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_44361

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_44361

125148

DOI: 10.1038/s41588-025-02368-y

Resource: None

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_125148

99373

DOI: 10.1038/s41588-025-02368-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_99373

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_99373

62205

DOI: 10.1038/s41588-025-02368-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_62205

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_62205

RRID:SCR_024672

DOI: 10.1038/s41588-025-02368-y

Resource: MapMyCells (RRID:SCR_024672)

Curator: @scibot

SciCrunch record: RRID:SCR_024672

102930

DOI: 10.1038/s41556-025-01774-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_102930

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_102930

MSP1E3D1

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-65037-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_20066

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_20066

p1E3D1

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-65037-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_20066

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_20066

87306

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-64742-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_87306

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_87306

121675

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-64742-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_121675

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_121675

114471

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-64742-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_114471

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_114471

50459

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-64742-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_50459

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_50459

44361

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-64742-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_44361

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_44361

40755

DOI: 10.1038/s41420-025-02789-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_40755

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_40755

60505

DOI: 10.1038/s41419-025-07952-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_60505

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_60505

80900

DOI: 10.1038/s41419-025-07952-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_80900

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_80900

83480

DOI: 10.1038/s41419-025-07952-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_83480

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_83480

11813

DOI: 10.1038/s41419-025-07952-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_11813

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_11813

12259

DOI: 10.1007/s12672-025-03889-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_12259

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_12259

Addgene_52961

DOI: 10.1007/s12672-025-03889-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_52961

Curator: @scibot

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_52961

Addgene_12260

DOI: 10.1007/s12672-025-03889-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_12260

Curator: @scibot

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_12260

Addgene_90237

DOI: 10.1038/s41598-025-23075-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_90237

Curator: @scibot

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_90237

plasmid_215559

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-63986-y

Resource: None

Curator: @scibot

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_215559

plasmid_45605

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-63986-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_45605

Curator: @scibot

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_45605

plasmid_117261

DOI: 10.1007/s11274-025-04598-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_117261

Curator: @scibot

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_117261

plasmid_117262

DOI: 10.1007/s11274-025-04598-y

Resource: None

Curator: @scibot

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_117262

Hola muy buenas noches quisiera poder pedirles respetuosamente el acceder al documento y obtenerlo descargado

Devine SM, O’Geen AT, Larsen RE, Dahlke HE, Liu H, Jin Y, Dahlgren RA. 2019. Microclimateforage growth linkages in a Mediterranean catchment in California’s Central Coast.Ecohydrology. 12(8):e2156

JP

12,260

DOI: 10.1186/s13024-025-00889-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_12260

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_12260

Addgene_96

DOI: 10.1186/s13024-025-00889-y

Resource: None

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_96808

Addgene_12

DOI: 10.1186/s13024-025-00889-y

Resource: None

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_12259

212936

DOI: 10.1186/s12931-025-03354-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_212936

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_212936

1015

DOI: 10.1186/s12929-025-01178-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_1015

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_1015

12259

DOI: 10.1038/s42255-025-01358-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_12259

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_12259

12260

DOI: 10.1038/s42255-025-01358-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_12260

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_12260

83356

DOI: 10.1038/s42255-025-01358-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_83356

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_83356

50054

DOI: 10.1038/s42255-025-01358-y

Resource: None

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_50054

98291

DOI: 10.1038/s42255-025-01358-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_98291

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_98291

52961

DOI: 10.1038/s42255-025-01358-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_52961

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_52961

79823

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09520-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_79823

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_79823

66810

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09520-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_66810

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_66810

48138

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09520-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_48138

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_48138

Addgene

DOI: 10.1038/s41523-025-00779-y

Resource: Addgene (RRID:SCR_002037)

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:SCR_002037

19131

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-65706-y

Resource: None

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_19131

171098

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-65706-y

Resource: None

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_171098

42230

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-65706-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_42230

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_42230

46569

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-65706-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_46569

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_46569

179392

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-65706-y

Resource: None

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_179392

psPAX2

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-63700-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_12260

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_12260

pMD2.G

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-63700-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_12259

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_12259

162076

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-63592-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_162076

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_162076

162075

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-63592-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_162075

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_162075

Plasmid_50005

DOI: 10.1038/s44172-025-00364-y

Resource: RRID:Addgene_50005

Curator: @scibot

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_50005

RRID:IMSR_JAX

DOI: 10.7554/eLife.100248

Resource: None

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:IMSR_JAX:000664

plasmid_6541359

DOI: 10.1038/s42003-025-08647-y

Resource: None

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_65413

plasmid_3295636

DOI: 10.1038/s42003-025-08647-y

Resource: None

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_32956

plasmid_2717358

DOI: 10.1038/s42003-025-08647-y

Resource: None

Curator: @olekpark

SciCrunch record: RRID:Addgene_27173

disminuir las creencias irracionales expuestas anteriormente, reemplazándolas por pensamientos alternativos que sean más adaptativos y permitan modificar la interpretación negativa que tiene R. de sí mismo y de su relación con otros. Disminuir el exceso de horas laborales para así, sustituirlas mediante actividades de ocio. Así como, desarrollar un adecuado manejo de la expresión emocional y un estilo de afrontamiento más funcional.

Objetivos

Existe una ley interna en la naturaleza a la que ningún ser vivo puede escapar. El cuerpo biológico nace, crece, madura y después decae hasta morir. Algunos pensadores, como Oswald Splenger, cayeron en el error de aplicar este mismo proceso a las sociedades humanas. Como respuesta a esta visión del desarrollo civilizatorio que le llevó a Spengler a escribir su famosa obra «La decadencia de Occidente», autores como Lewis Mumford o Waldo Frank defendieron que las comunidades orgánicas presentan una forma parabólica, siempre abierta y cambiante. El término elegido por Mumford para definir este proceso fue el de «equilibrio dinámico»

¿Es una comunidad orgánica un símil de una [[cibernética]] positiva y abierta? ¿Es posible pensarlo desde ahí?

El reto que tenemos ante nosotros, la revolución esperada, es el triunfo de la visión orgánica. Este momento llegará, según Waldo Frank, cuando el hombre, «que durante dilatadas épocas ha empleado todos sus órganos individuales y colectivos para el bienestar del yo, empíricamente considerado, aprenda que este yo, así cuidado y así servido, pierde su salud: que por su bienestar debe esforzarse en ser un integrador dentro de un todo metafísicamente fuera de él». En resumidas cuentas, nuestra misión futura consiste en la reordenación de los tres componentes del yo: el ego social, el ego somático y el yo cósmico. Este último, el espíritu, con capacidad infinita para elevarse, tiene que ocupar el lugar central, hoy día monopolizado por el ego somático, dando lugar al egoísmo e individualismo reinante. Este proceso de reacondicionamiento interno está todavía en sus primeras etapas y aparece fugazmente en ocasiones puntuales que calificamos de «revolucionarias».

Interesante posibilidad para cruzar con el #TFM y la cuestión del #encantamiento

Después de mucho tiempo dándole vueltas a la cabeza, he llegado a la misma conclusión a la que llegaron Lewis Mumford y su colega Waldo Frank: uno de los asuntos claves en la humanidad y en su modo de organización como sociedad es el eterno conflicto en la visión mecánica y la visión orgánica de la existencia humana y todo lo que con ella se relaciona. La primera de las visiones se relaciona con la máquina, la segunda con la naturaleza. Cada día este eterno conflicto entre mecanicismo y organicismo se aprecia con más claridad. El escenario donde se libra la batalla entre mecanicista y organicista ha sido y es de lo más variado. En arquitectura, Frank Lloyd Wright y Antoni Gaudí frente a Le Corbusier y los representantes del llamado «Estilo Internacional»; en la música, Mozart frente a la música electrónica; el cerebro frente a la inteligencia artificial; el proyecto educativo de Dewey frente a los postulados de Comenius; la pintura de Goya frente a los cuadros de Andy Warhol; la medicina natural frente a la institucional, etc…

[[Lewis Mumford]] y [[Waldo Frank]] sobre el conflicto de la visión mecánica u orgánica.

Términos como organismo, mecanicismo, organización, 15M, democracia, política,…, son las piezas claves del puzzle y una metáfora en sí misma de la idea principal que las une a todas: la relación entre el todo y las partes.

Sobre [[mecanicismo]] y [[organicismo]].

P element allele of vps24, yw;;P w+y+ vps24[EY04708]

DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251184

Resource: Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (RRID:SCR_006457)

Curator: @bdscstockkeepers

SciCrunch record: RRID:SCR_006457

Supplementary Information

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-58478-y

Resource: (WB Cat# WBStrain00004840,RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00004840)

Curator: @Apiekniewska

SciCrunch record: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00004840

Supplementary Information

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-58478-y

Resource: (WB Cat# WBStrain00000001,RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00000001)

Curator: @Apiekniewska

SciCrunch record: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00000001

Supplementary Information

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-58478-y

Resource: None

Curator: @Apiekniewska

SciCrunch record: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00006376

Supplementary Information

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-58478-y

Resource: None

Curator: @Apiekniewska

SciCrunch record: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00027365

Supplementary Information

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-58478-y

Resource: None

Curator: @Apiekniewska

SciCrunch record: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00041003

Supplementary Information

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-58478-y

Resource: None

Curator: @Apiekniewska

SciCrunch record: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00007572

Supplementary Information

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-58478-y

Resource: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00027424

Curator: @Apiekniewska

SciCrunch record: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00027424

Supplementary Information

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-58478-y

Resource: None

Curator: @Apiekniewska

SciCrunch record: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00005261

Supplementary Information

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-58478-y

Resource: (WB Cat# WBStrain00041969,RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00041969)

Curator: @Apiekniewska

SciCrunch record: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00041969

Supplementary Information

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-58478-y

Resource: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00027363

Curator: @Apiekniewska

SciCrunch record: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00027363

Supplementary Information

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-58478-y

Resource: None

Curator: @Apiekniewska

SciCrunch record: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00022773

Supplementary Information

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-58478-y

Resource: (WB Cat# WBStrain00040806,RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00040806)

Curator: @Apiekniewska

SciCrunch record: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00040806

Supplementary Information

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-58478-y

Resource: None

Curator: @Apiekniewska

SciCrunch record: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00022197

Supplementary Information

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-58478-y

Resource: (WB Cat# WBStrain00024040,RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00024040)

Curator: @Apiekniewska

SciCrunch record: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00024040

Supplementary Information

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-58478-y

Resource: None

Curator: @Apiekniewska

SciCrunch record: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00005327

Supplementary Information

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-58478-y

Resource: None

Curator: @Apiekniewska

SciCrunch record: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00022768

Supplementary Information

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-58478-y

Resource: None

Curator: @Apiekniewska

SciCrunch record: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00026779

Supplementary Information

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-58478-y

Resource: None

Curator: @Apiekniewska

SciCrunch record: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00022771

Supplementary Information

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-58478-y

Resource: None

Curator: @Apiekniewska

SciCrunch record: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00022185

Supplementary Information

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-58478-y

Resource: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00004310

Curator: @Apiekniewska

SciCrunch record: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00004310

Supplementary Information

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-58478-y

Resource: None

Curator: @Apiekniewska

SciCrunch record: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00031767

Supplementary Information

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-58478-y

Resource: None

Curator: @Apiekniewska

SciCrunch record: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00005487

Supplementary Information

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-58478-y

Resource: (WB Cat# WBStrain00034065,RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00034065)

Curator: @Apiekniewska

SciCrunch record: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00034065

Supplementary Information

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-58478-y

Resource: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00000264

Curator: @Apiekniewska

SciCrunch record: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00000264

Supplementary Information

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-58478-y

Resource: None

Curator: @Apiekniewska

SciCrunch record: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00029930

Supplementary Information

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-58478-y

Resource: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00008608

Curator: @Apiekniewska

SciCrunch record: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00008608

Supplementary Information

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-58478-y

Resource: None

Curator: @Apiekniewska

SciCrunch record: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00031144

Supplementary Information

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-58478-y

Resource: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00008309

Curator: @Apiekniewska

SciCrunch record: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00008309

Supplementary Information

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-58478-y

Resource: None

Curator: @Apiekniewska

SciCrunch record: RRID:WB-STRAIN:WBStrain00029100

Dossier d'Information : La Quête de la Parentalité Idéale

Ce document synthétise une discussion radiophonique sur la notion de "bon parent", explorant les pressions, les doutes et les stratégies qui définissent la parentalité contemporaine.

Il ressort que l'idéal du parent parfait est une source de stress et de culpabilité, largement alimentée par la compétition sociale et un afflux de connaissances scientifiques qui peuvent être à la fois une aide et un fardeau.

Les intervenants s'accordent sur le fait que la parentalité est un exercice d'équilibriste constant, oscillant entre de grands succès et des échecs patents.

Les thèmes centraux incluent le conflit entre le désir de façonner un "enfant idéal" et la nécessité d'accepter l'enfant réel, la difficulté de se défaire de ses propres projections et traumatismes, et la charge mentale disproportionnée qui pèse souvent sur les mères.

La discussion met en lumière le concept de "parent suffisamment bon" de Donald Winnicott, qui valorise non pas la perfection, mais la capacité à répondre aux besoins de l'enfant tout en introduisant une frustration gérable, essentielle à son développement.

Finalement, la parentalité est présentée comme une expérience partagée, où l'échange, la reconnaissance de sa propre faillibilité et la capacité à "réparer" ses erreurs sont plus importants que la poursuite d'un idéal inaccessible.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

La question "Qu'est-ce qu'un bon parent ?" a fait l'objet d'une émission sur France Inter, réunissant des chroniqueurs, auteurs et parents pour partager leurs expériences et réflexions.

La discussion, présentée comme une conversation de "praticiens" plutôt que de spécialistes, a exploré les multiples facettes de la parentalité moderne.

Intervenants Principaux :

Nom

Rôle et Affiliation

Nombre d'enfants

Gwenaëlle Boulet

Rédactrice en chef (Popie, Pomme d'Api), autrice de la BD "Ma vie de parent"

Trois

Julien Bisson

Directeur des rédactions (Le 1 hebdo), chroniqueur "Ma vie de parent"

Un

Marie Pernaud

Chroniqueuse (La maison des maternels), animatrice du podcast "Very Important Parents"

Quatre

Sonia de Viller

Journaliste et parente intervenant au cours du débat

Deux (au moins)

Le débat a également été enrichi par les témoignages d'auditeurs, offrant des perspectives vécues sur les défis abordés.

La discussion s'ouvre sur un exercice d'auto-notation, demandant aux invités de s'évaluer sur une échelle de 1 (parent exécrable) à 10 (parent parfait).

Les réponses révèlent immédiatement la complexité et la variabilité de la perception de soi en tant que parent.

• Gwenaëlle Boulet se donne un 8/10, justifiant cette note élevée par le fait que ses enfants n'ont pas été maltraités et vont globalement bien, tout en admettant leur laisser "suffisamment de quoi aller chez le psy plus tard".

• Julien Bisson souligne la fluctuation de sa performance : il s'évalue à 9/10 la veille au soir après un jeu de société, mais à 2/10 le matin même après avoir "hurlé sur son fils". Sa moyenne se situe donc autour de 5,5/10.

• Marie Pernaud abonde dans ce sens, affirmant que la qualité de sa parentalité varie selon les moments de la journée, notant que "le matin, c'est compliqué quand même".

• Florence, une auditrice de Haute-Savoie, se donne une moyenne de 7,5/10, reconnaissant que sa performance dépend des "circonstances de la vie".

Cette variabilité démontre que la parentalité n'est pas une compétence statique, mais un effort constant et situationnel.

Un thème majeur émerge rapidement : la tension entre l'enfant que les parents désirent et l'enfant qu'ils ont réellement.

• Florence, l'auditrice, définit le bon parent comme celui qui, dès la naissance, considère son enfant "comme un être à part entière" et non "comme sa possession".

L'objectif est de l'aider à se réaliser "selon ce qu'il est lui et non pas ce que je voulais moi, ce qui soit".

• Gwenaëlle Boulet confesse que c'est le "combat de sa vie".

Elle illustre cette lutte avec son désir que ses enfants aiment la littérature, un désir qui s'est heurté à leur indifférence et s'est avéré "contreproductif à souhait".

Elle trouve "hyper dur" d'accepter que son enfant puise "dans d'autres sources que les tiennes pour grandir".

• Julien Bisson conclut que pour s'approcher du "parent idéal", il faut d'abord "éviter de vouloir un enfant idéal".

Cet enfant idéal est celui sur lequel on projette ses propres attentes psychologiques et d'accomplissement.

• Marie Pernaud résume : être un bon parent, "c'est vraiment faire le deuil de l'enfant qu'on aurait voulu avoir".

Face à un conflit, la question à se poser est : "quel est l'enfant qu'on a en fait et comment on doit réagir par rapport à l'enfant qu'on a".

Sonia de Viller ajoute une nuance importante : on n'est pas le même parent pour chaque enfant.

"Je suis pas la même mère avec mon fils aîné et mon cadet et d'ailleurs il me le reproche".

Marie Pernaud confirme que chaque enfant révèle des facettes différentes, positives comme négatives, chez le parent.

La discussion met en évidence que la parentalité contemporaine est soumise à une série de pressions externes et internes qui complexifient la tâche.

L'accès à une masse d'informations sur le développement de l'enfant est perçu comme une arme à double tranchant.

• Gwenaëlle Boulet utilise l'analogie de l'effet Dunning-Kruger :

1. La "montagne de la stupidité" : Fin 19e/début 20e, les exigences se limitaient à s'assurer que l'enfant ne meure pas.

2. La "vallée de l'humilité" : L'arrivée de la psychanalyse et des neurosciences a fait chuter la confiance des parents, écrasés par les connaissances sur ce qu'il "faut surtout pas faire".

3. Le "plateau de la consolidation" : L'objectif est de remonter en faisant correspondre sa confiance et ses compétences, en utilisant ces connaissances tout en se faisant confiance.

• Julien Bisson qualifie les sciences de l'éducation de "bénédiction et malédiction".

Une bénédiction pour les savoirs apportés, une malédiction car elles "ont creusé énormément la distance entre le parent qu'on a l'impression d'être et le parent qu'on pense devoir être", créant un "mal-être parental énorme".

La société moderne impose une dynamique de comparaison et d'individualisme qui affecte directement les parents.

• La Compétition Parentale : Gwenaëlle Boulet décrit une "compète" ressentie dès la maternité (choisir la "super maternité") et qui se poursuit avec la scolarité (l'âge d'apprentissage de la lecture).

• L'Isolement : Julien Bisson lie cette compétition à une société avec "plus d'individualisme, plus d'isolement", ce qui renforce le sentiment d'être "seul" et "désarmé".

• Témoignage de Charlotte : Une auditrice d'Aix-en-Provence exprime sa difficulté à "créer une communauté de parents".

Elle se sent comme une "extraterrestre" lorsqu'elle propose des initiatives collectives ou parle de l'éducation au "vivre ensemble".

La recherche de la perfection parentale a un coût direct sur le bien-être des parents.

• Marie Pernaud alerte sur le risque d'épuisement face aux "injonctions". Les parents reçoivent une multitude d'informations et pensent devoir "absolument tout faire".

Elle rappelle le propos d'une Danoise : tant qu'il n'y a ni maltraitance et qu'il y a de l'amour, il ne peut y avoir de mauvaise éducation.

• Julien Bisson cite des chiffres issus d'un numéro du 1 hebdo sur la santé mentale des parents :

◦ Le mal-être parental touche 1 parent sur 5 (20%).

◦ Le burnout parental affecte 6 à 8 % des parents.

◦ Les femmes sont plus touchées, non par fragilité, mais parce qu'elles "portent encore aujourd'hui une charge parentale beaucoup plus importante que les hommes".

Face à l'idéal inaccessible, la discussion propose une approche plus réaliste et bienveillante, inspirée du concept du psychanalyste Donald Winnicott.

• Définition : Un parent suffisamment bon répond aux besoins de l'enfant sans être parfait et sans "faire trop".

• Évolution :

1. Nourrisson : Le parent répond immédiatement et exactement aux besoins du bébé (faim, réconfort).

2. Enfant : Le parent instaure progressivement "de la frustration gérable".

Il apprend à l'enfant à différer ses désirs, ce qui l'aide à grandir et à "vivre en société".

• Risque de l'anticipation : Anticiper systématiquement les besoins de l'enfant peut freiner son autonomie et son développement émotionnel.

L'erreur n'est pas seulement inévitable, elle est une composante de la relation.

• Reconnaître ses erreurs : Gwenaëlle Boulet insiste sur l'importance de pouvoir revenir vers son enfant et dire :

"Je suis désolé, je me suis emballée [...] j'avais pas envie de réagir comme ça". Cela permet de "réparer beaucoup de choses".

• Déculpabiliser l'enfant : Julien Bisson ajoute que cela aide l'enfant à comprendre que ce n'est "pas toujours de sa faute", car son objectif principal est de satisfaire ses parents.

• Le "Faux Choix" : Gwenaëlle Boulet partage une technique concrète : au lieu de demander "Tu veux prendre ta douche ?", poser la question "Tu veux prendre ta douche maintenant ou dans 5 minutes ?".

Cela offre à l'enfant un "terrain d'expérimentation du choix" tout en atteignant l'objectif du parent.

• L'Influence Partagée : Julien Bisson utilise la métaphore du "buffet" : le parent offre un buffet, mais ne contrôle pas ce que l'enfant va choisir.

De plus, il n'est "pas le seul à le nourrir" (grands-parents, amis, etc.). Il ne faut pas surestimer sa propre influence.

• Le Duo Parental : L'ajustement entre les deux parents, avec leurs bagages respectifs, est un défi mais aussi ce qui "sauve", permettant de prendre de la distance.

Intervenant/Source

Citation ou Idée Clé

Fiva (auditeur)

"Le parent parfait existe mais il n'a pas encore d'enfant."

Cécile Dancy (auditeur)

"Être un bon parent, c'est déjà être capable de travailler ses propres failles pour ne pas les faire peser sur nos enfants."

Peter Ustinov (cité)

"Les parents sont les os sur lesquelles les enfants se font les dents."

Russell Show (cité)

"Si nous accordons à nos enfants notre confiance, si nous les laissons suivre leur propre voix (...) nous allégerons notre vie tout en leur donnant les moyens de s'épanouir."

Ivan (auditeur)

Témoigne avec une grande émotion de sa souffrance en tant que père de deux adolescents.

Il reconnaît avoir projeté des attentes élevées sur son fils aîné, en réaction à sa propre relation difficile avec son père, ce qui a mené à une "cassure".

Il exprime son désarroi face à une situation complexe, concluant : "un bon parent, je ne sais pas ce que c'est [...] c'est simplement essayer de faire du mieux que je peux".

Le témoignage d'Ivan illustre de manière poignante le poids du passé, le risque de la surprotection et le sentiment de désarroi que peuvent ressentir les parents, même avec la volonté de bien faire.

Sa démarche de s'interroger, selon les intervenants, est déjà la preuve qu'il est "probablement un bon parent".

Warning in left_join(., secondary_data %>% select("PASSWORD", "VEGGIESCORE", : Detected an unexpected many-to-many relationship between `x` and `y`. ℹ Row 1 of `x` matches multiple rows in `y`. ℹ Row 86 of `y` matches multiple rows in `x`. ℹ If a many-to-many relationship is expected, set `relationship = "many-to-many"` to silence this warning.

remove warnings

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Summary:

In this study, participants completed two different tasks. A perceptual choice task in which they compared the sizes of pairs of items and a value-different task in which they identified the higher value option among pairs of items with the two tasks involving the same stimuli. Based on previous fMRI research, the authors sought to determine whether the superior frontal sulcus (SFS) is involved in both perceptual and value-based decisions or just one or the other. Initial fMRI analyses were devised to isolate brain regions that were activated for both types of choices and also regions that were unique to each. Transcranial magnetic stimulation was applied to the SFS in between fMRI sessions and it was found to lead to a significant decrease in accuracy and RT on the perceptual choice task but only a decrease in RT on the value-different task. Hierarchical drift-diffusion modelling of the data indicated that the TMS had led to a lowering of decision boundaries in the perceptual task and a lower of non-decision times on the value-based task. Additional analyses show that SFS covaries with model-derived estimates of cumulative evidence and that this relationship is weakened by TMS.

Strengths:

The paper has many strengths including the rigorous multi-pronged approach of causal manipulation, fMRI and computational modelling which offers a fresh perspective on the neural drivers of decision making. Some additional strengths include the careful paradigm design which ensured that the two types of tasks were matched for their perceptual content while orthogonalizing trial-to-trial variations in choice difficulty. The paper also lays out a number of specific hypotheses at the outset regarding the behavioural outcomes that are tied to decision model parameters and are well justified.

Weaknesses:

(1.1) Unless I have missed it, the SFS does not actually appear in the list of brain areas significantly activated by the perceptual and value tasks in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. Its presence or absence from the list of significant activations is not mentioned by the authors when outlining these results in the main text. What are we to make of the fact that it is not showing significant activation in these initial analyses?

You are right that the left SFS does not appear in our initial task-level contrasts. Those first analyses were deliberately agnostic to evidence accumulation (i.e., average BOLD by task, irrespective of trial-by-trial evidence). Consistent with prior work, SFS emerges only when we model the parametric variation in accumulated perceptual evidence.

Accordingly, we ran a second-level GLM that included trial-wise accumulated evidence (aE) as a parametric modulator. In that analysis, the left SFS shows significant aE-related activity specifically during perceptual decisions, but not during value-based decisions (SVC in a 10-mm sphere around x = −24, y = 24, z = 36).

To avoid confusion, we now:

(i) explicitly separate and label the two analysis levels in the Results; (ii) state up front that SFS is not expected to appear in the task-average contrast; and (iii) add a short pointer that SFS appears once aE is included as a parametric modulator. We also edited Methods to spell out precisely how aE is constructed and entered into GLM2. This should make the logic of the two-stage analysis clearer and aligns the manuscript with the literature where SFS typically emerges only in parametric evidence models.

(1.2) The value difference task also requires identification of the stimuli, and therefore perceptual decision-making. In light of this, the initial fMRI analyses do not seem terribly informative for the present purposes as areas that are activated for both types of tasks could conceivably be specifically supporting perceptual decision-making only. I would have thought brain areas that are playing a particular role in evidence accumulation would be best identified based on whether their BOLD response scaled with evidence strength in each condition which would make it more likely that areas particular to each type of choice can be identified. The rationale for the authors' approach could be better justified.

We agree that both tasks require early sensory identification of the items, but the decision-relevant evidence differs by design (size difference vs. value difference), and our modelling is targeted at the evidence integration stage rather than initial identification.

To address your concern empirically, we: (i) added session-wise plots of mean RTs showing a general speed-up across the experiment (now in the Supplement); (ii) fit a hierarchical DDM to jointly explain accuracy and RT. The DDM dissociates decision time (evidence integration) from non-decision time (encoding/response execution).

After cTBS, perceptual decisions show a selective reduction of the decision boundary (lower accuracy, faster RTs; no drift-rate change), whereas value-based decisions show no change to boundary/drift but a decrease in non-decision time, consistent with faster sensorimotor processing or task familiarity. Thus, the TMS effect in SFS is specific to the criterion for perceptual evidence accumulation, while the RT speed-up in the value task reflects decision-irrelevant processes. We now state this explicitly in the Results and add the RT-by-run figure for transparency.

(1.2.1) The value difference task also requires identification of the stimuli, and therefore perceptual decision-making. In light of this, the initial fMRI analyses do not seem terribly informative for the present purposes as areas that are activated for both types of tasks could conceivably be specifically supporting perceptual decision-making only.

Thank you for prompting this clarification.

The key point is what changes with cTBS. If SFS supported generic identification, we would expect parallel cTBS effects on drift rate (or boundary) in both tasks. Instead, we find: (a) boundary decreases selectively in perceptual decisions (consistent with SFS setting the amount of perceptual evidence required), and (b) non-decision time decreases selectively in the value task (consistent with speed-ups in encoding/response stages). Moreover, trial-by-trial SFS BOLD predicts perceptual accuracy (controlling for evidence), and neural-DDM model comparison shows SFS activity modulates boundary, not drift, during perceptual choices.

Together, these converging behavioral, computational, and neural results argue that SFS specifically supports the criterion for perceptual evidence accumulation rather than generic visual identification.

(1.2.2) I would have thought brain areas that are playing a particular role in evidence accumulation would be best identified based on whether their BOLD response scaled with evidence strength in each condition which would make it more likely that areas particular to each type of choice can be identified. The rationale for the authors' approach could be better justified.

We now more explicitly justify the two-level fMRI approach. The task-average contrast addresses which networks are generally more engaged by each domain (e.g., posterior parietal for PDM; vmPFC/PCC for VDM), given identical stimuli and motor outputs. This complements, but does not substitute for, the parametric evidence analysis, which is where one expects accumulation-related regions such as SFS to emerge. We added text clarifying that the first analysis establishes domain-specific recruitment at the task level, whereas the second isolates evidence-dependent signals (aE) and reveals that left SFS tracks accumulated evidence only for perceptual choices. We also added explicit references to the literature using similar two-step logic and noted that SFS typically appears only in parametric evidence models.

(1.3) TMS led to reductions in RT in the value-difference as well as the perceptual choice task. DDM modelling indicated that in the case of the value task, the effect was attributable to reduced non-decision time which the authors attribute to task learning. The reasoning here is a little unclear.

(1.3.1) Comment: If task learning is the cause, then why are similar non-decision time effects not observed in the perceptual choice task?

Great point. The DDM addresses exactly this: RT comprises decision time (DT) plus non-decision time (nDT). With cTBS, PDM shows reduced DT (via a lower boundary) but stable nDT; VDM shows reduced nDT with no change to boundary/drift. Hence, the superficially similar RT speed-ups in both tasks are explained by different latent processes: decision-relevant in PDM (lower criterion → faster decisions, lower accuracy) and decision-irrelevant in VDM (faster encoding/response). We added explicit language and a supplemental figure showing RT across runs, and we clarified in the text that only the PDM speed-up reflects a change to evidence integration.

(1.3.2) Given that the value-task actually requires perceptual decision-making, is it not possible that SFS disruption impacted the speed with which the items could be identified, hence delaying the onset of the value-comparison choice?

We agree there is a brief perceptual encoding phase at the start of both tasks. If cTBS impaired visual identification per se, we would expect longer nDT in both tasks or a decrease in drift rate. Instead, nDT decreases in the value task and is unchanged in the perceptual task; drift is unchanged in both. Thus, cTBS over SFS does not slow identification; rather, it lowers the criterion for perceptual accumulation (PDM) and, separately, we observe faster non-decision components in VDM (likely familiarity or motor preparation). We added a clarifying sentence noting that item identification was easy and highly overlearned (static, large food pictures), and we cite that nDT is the appropriate locus for identification effects in the DDM framework; our data do not show the pattern expected of impaired identification.

(1.4) The sample size is relatively small. The authors state that 20 subjects is 'in the acceptable range' but it is not clear what is meant by this.

We have clarified what we mean and provided citations. The sample (n = 20) matches or exceeds many prior causal TMS/fMRI studies targeting perceptual decision circuitry (e.g., Philiastides et al., 2011; Rahnev et al., 2016; Jackson et al., 2021; van der Plas et al., 2021; Murd et al., 2021). Importantly, we (i) use within-subject, pre/post cTBS differences-in-differences with matched tasks; (ii) estimate hierarchical models that borrow strength across participants; and (iii) converge across behavior, latent parameters, regional BOLD, and connectivity. We now replace the vague phrase with a concrete statement and references, and we report precision (HDIs/SEs) for all main effects.

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Summary:

The authors set out to test whether a TMS-induced reduction in excitability of the left Superior Frontal Sulcus influenced evidence integration in perceptual and value-based decisions. They directly compared behaviour - including fits to a computational decision process model - and fMRI pre and post-TMS in one of each type of decision-making task. Their goal was to test domain-specific theories of the prefrontal cortex by examining whether the proposed role of the SFS in evidence integration was selective for perceptual but not value-based evidence.

Strengths:

The paper presents multiple credible sources of evidence for the role of the left SFS in perceptual decision-making, finding similar mechanisms to prior literature and a nuanced discussion of where they diverge from prior findings. The value-based and perceptual decision-making tasks were carefully matched in terms of stimulus display and motor response, making their comparison credible.

Weaknesses:

(2.1) More information on the task and details of the behavioural modelling would be helpful for interpreting the results.

Thank you for this request for clarity. In the revision we explicitly state, up front, how the two tasks differ and how the modelling maps onto those differences.

(1) Task separability and “evidence.” We now define task-relevant evidence as size difference (SD) for perceptual decisions (PDM) and value difference (VD) for value-based decisions (VDM). Stimuli and motor mappings are identical across tasks; only the evidence to be integrated changes.

(2) Behavioural separability that mirrors task design. As reported, mixed-effects regressions show PDM accuracy increases with SD (β=0.560, p<0.001) but not VD (β=0.023, p=0.178), and PDM RTs shorten with SD (β=−0.057, p<0.001) but not VD (β=0.002, p=0.281). Conversely, VDM accuracy increases with VD (β=0.249, p<0.001) but not SD (β=0.005, p=0.826), and VDM RTs shorten with VD (β=−0.016, p=0.011) but not SD (β=−0.003, p=0.419).

(3 How the HDDM reflects this. The hierarchical DDM fits the joint accuracy–RT distributions with task-specific evidence (SD or VD) as the predictor of drift. The model separates decision time from non-decision time (nDT), which is essential for interpreting the different RT patterns across tasks without assuming differences in the accumulation process when accuracy is unchanged.

These clarifications are integrated in the Methods (Experimental paradigm; HDDM) and in Results (“Behaviour: validity of task-relevant pre-requisites” and “Modelling: faster RTs during value-based decisions is related to non-decision-related sensorimotor processes”).

(2.2) The evidence for a choice and 'accuracy' of that choice in both tasks was determined by a rating task that was done in advance of the main testing blocks (twice for each stimulus). For the perceptual decisions, this involved asking participants to quantify a size metric for the stimuli, but the veracity of these ratings was not reported, nor was the consistency of the value-based ones. It is my understanding that the size ratings were used to define the amount of perceptual evidence in a trial, rather than the true size differences, and without seeing more data the reliability of this approach is unclear. More concerning was the effect of 'evidence level' on behaviour in the value-based task (Figure 3a). While the 'proportion correct' increases monotonically with the evidence level for the perceptual decisions, for the value-based task it increases from the lowest evidence level and then appears to plateau at just above 80%. This difference in behaviour between the two tasks brings into question the validity of the DDM which is used to fit the data, which assumes that the drift rate increases linearly in proportion to the level of evidence.

We thank the reviewer for raising these concerns, and we address each of them point by point:

2.2.1. Comment: It is my understanding that the size ratings were used to define the amount of perceptual evidence in a trial, rather than the true size differences, and without seeing more data the reliability of this approach is unclear.

That is correct—we used participants’ area/size ratings to construct perceptual evidence (SD).

To validate this choice, we compared those ratings against an objective image-based size measure (proportion of non-black pixels within the bounding box). As shown in Author response image 3, perceptual size ratings are highly correlated with objective size across participants (Pearson r values predominantly ≈0.8 or higher; all p<0.001). Importantly, value ratings do not correlate with objective size (Author response image 2), confirming that the two rating scales capture distinct constructs. These checks support using participants’ size ratings as the participant-specific ground truth for defining SD in the PDM trials.

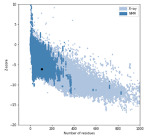

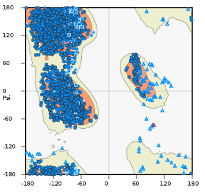

Author response image 1.

Objective size and value ratings are unrelated. Scatterplots show, for each participant, the correlation between objective image size (x-axis; proportion of non-black pixels within the item box) and value-based ratings (y-axis; 0–100 scale). Each dot is one food item (ratings averaged over the two value-rating repetitions). Across participants, value ratings do not track objective size, confirming that value and size are distinct constructs.

Author response image 2.

Perceptual size ratings closely track objective size. Scatterplots show, for each participant, the correlation between objective image size (x-axis) and perceptual area/size ratings (y-axis; 0–100 scale). Each dot is one food item (ratings averaged over the two perceptual ratings). Perceptual ratings are strongly correlated with objective size for nearly all participants (see main text), validating the use of these ratings to construct size-difference evidence (SD).

(2.2.2) More concerning was the effect of 'evidence level' on behaviour in the value-based task (Figure 3a). While the 'proportion correct' increases monotonically with the evidence level for the perceptual decisions, for the value-based task it increases from the lowest evidence level and then appears to plateau at just above 80%. This difference in behaviour between the two tasks brings into question the validity of the DDM which is used to fit the data, which assumes that the drift rate increases linearly in proportion to the level of evidence.

We agree that accuracy appears to asymptote in VDM, but the DDM fits indicate that the drift rate still increases monotonically with evidence in both tasks. In Supplementary figure 11, drift (δ) rises across the four evidence levels for PDM and for VDM (panels showing all data and pre/post-TMS). The apparent plateau in proportion correct during VDM reflects higher choice variability at stronger preference differences, not a failure of the drift–evidence mapping. Crucially, the model captures both the accuracy patterns and the RT distributions (see posterior predictive checks in Supplementary figures 11-16), indicating that a monotonic evidence–drift relation is sufficient to account for the data in each task.

Author response image 3.

HDDM parameters by evidence level. Group-level posterior means (± posterior SD) for drift (δ), boundary (α), and non-decision time (τ) across the four evidence levels, shown (a) collapsed across TMS sessions, (b) for PDM (blue) pre- vs post-TMS (light vs dark), and (c) for VDM (orange) pre- vs post-TMS. Crucially, drift increases monotonically with evidence in both tasks, while TMS selectively lowers α in PDM and reduces τ in VDM (see Supplementary Tables for numerical estimates).

(2.3) The paper provides very little information on the model fits (no parameter estimates, goodness of fit values or simulated behavioural predictions). The paper finds that TMS reduced the decision bound for perceptual decisions but only affected non-decision time for value-based decisions. It would aid the interpretation of this finding if the relative reliability of the fits for the two tasks was presented.

We appreciate the suggestion and have made the quantitative fit information explicit:

(1) Parameter estimates. Group-level means/SDs for drift (δ), boundary (α), and nDT (τ) are reported for PDM and VDM overall, by evidence level, pre- vs post-TMS, and per subject (see Supplementary Tables 8-11).

(2) Goodness of fit and predictive adequacy. DIC values accompany each fit in the tables. Posterior predictive checks demonstrate close correspondence between simulated and observed accuracy and RT distributions overall, by evidence level, and across subjects (Supplementary Figures 11-16).

Together, these materials document that the HDDM provides reliable fits in both tasks and accurately recovers the qualitative and quantitative patterns that underlie our inferences (reduced α for PDM only; selective τ reduction in VDM).

(2.4) Behaviourally, the perceptual task produced decreased response times and accuracy post-TMS, consistent with a reduced bound and consistent with some prior literature. Based on the results of the computational modelling, the authors conclude that RT differences in the value-based task are due to task-related learning, while those in the perceptual task are 'decision relevant'. It is not fully clear why there would be such significantly greater task-related learning in the value-based task relative to the perceptual one. And if such learning is occurring, could it potentially also tend to increase the consistency of choices, thereby counteracting any possible TMS-induced reduction of consistency?

Thank you for pointing out the need for a clearer framing. We have removed the speculative label “task-related learning” and now describe the pattern strictly in terms of the HDDM decomposition and neural results already reported:

(1) VDM: Post-TMS RTs are faster while accuracy is unchanged. The HDDM attributes this to a selective reduction in non-decision time (τ), with no change in decision-relevant parameters (α, δ) for VDM (see Supplementary Figure 11 and Supplementary Tables). Consistent with this, left SFS BOLD is not reduced for VDM, and trialwise SFS activity does not predict VDM accuracy—both observations argue against a change in VDM decision formation within left SFS.

(2) PDM: Post-TMS accuracy decreases and RTs shorten, which the HDDM captures as a lower decision boundary (α) with no change in drift (δ). Here, left SFS BOLD scales with accumulated evidence and decreases post-TMS, and trialwise SFS activity predicts PDM accuracy, all consistent with a decision-relevant effect in PDM.

Regarding the possibility that faster VDM RTs should increase choice consistency: empirically, consistency did not change in VDM, and the HDDM finds no decision-parameter shifts there. Thus, there is no hidden counteracting increase in VDM accuracy that could mask a TMS effect—the absence of a VDM accuracy change is itself informative and aligns with the modelling and fMRI.

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

Summary:

Garcia et al., investigated whether the human left superior frontal sulcus (SFS) is involved in integrating evidence for decisions across either perceptual and/or value-based decision-making. Specifically, they had 20 participants perform two decision-making tasks (with matched stimuli and motor responses) in an fMRI scanner both before and after they received continuous theta burst transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) of the left SFS. The stimulation thought to decrease neural activity in the targeted region, led to reduced accuracy on the perceptual decision task only. The pattern of results across both model-free and model-based (Drift diffusion model) behavioural and fMRI analyses suggests that the left SLS plays a critical role in perceptual decisions only, with no equivalent effects found for value-based decisions. The DDM-based analyses revealed that the role of the left SLS in perceptual evidence accumulation is likely to be one of decision boundary setting. Hence the authors conclude that the left SFS plays a domain-specific causal role in the accumulation of evidence for perceptual decisions. These results are likely to add importance to the literature regarding the neural correlates of decision-making.

Strengths:

The use of TMS strengthens the evidence for the left SFS playing a causal role in the evidence accumulation process. By combining TMS with fMRI and advanced computational modelling of behaviour, the authors go beyond previous correlational studies in the field and provide converging behavioural, computational, and neural evidence of the specific role that the left SFS may play.

Sophisticated and rigorous analysis approaches are used throughout.

Weaknesses:

(3.1) Though the stimuli and motor responses were equalised between the perception and value-based decision tasks, reaction times (according to Figure 1) and potential difficulty (Figure 2) were not matched. Hence, differences in task difficulty might represent an alternative explanation for the effects being specific to the perception task rather than domain-specificity per se.

We agree that RTs cannot be matched a priori, and we did not intend them to be. Instead, we equated the inputs to the decision process and verified that each task relied exclusively on its task-relevant evidence. As reported in Results—Behaviour: validity of task-relevant pre-requisites (Fig. 1b–c), accuracy and RTs vary monotonically with the appropriate evidence regressor (SD for PDM; VD for VDM), with no effect of the task-irrelevant regressor. This separability check addresses differences in baseline RTs by showing that, for both tasks, behaviour tracks evidence as designed.

To rule out a generic difficulty account of the TMS effect, we relied on the within-subject differences-in-differences (DID) framework described in Methods (Differences-in-differences). The key Task × TMS interaction compares the pre→post change in PDM with the pre→post change in VDM while controlling for trialwise evidence and RT covariates. Any time-on-task or unspecific difficulty drift shared by both tasks is subtracted out by this contrast. Using this specification, TMS selectively reduced accuracy for PDM but not VDM (Fig. 3a; Supplementary Fig. 2a,c; Supplementary Tables 5–7).

Finally, the hierarchical DDM (already in the paper) dissociates latent mechanisms. The post-TMS boundary reduction appears only in PDM, whereas VDM shows a change in non-decision time without a decision-relevant parameter change (Fig. 3c; Supplementary Figs. 4–5). If unmatched difficulty were the sole driver, we would expect parallel effects across tasks, which we do not observe.

(3.2) No within- or between-participants sham/control TMS condition was employed. This would have strengthened the inference that the apparent TMS effects on behavioural and neural measures can truly be attributed to the left SFS stimulation and not to non-specific peripheral stimulation and/or time-on-task effects.

We agree that a sham/control condition would further strengthen causal attribution and note this as a limitation. In mitigation, our design incorporates several safeguards already reported in the manuscript:

· Within-subject pre/post with alternating task blocks and DID modelling (Methods) to difference out non-specific time-on-task effects.

· Task specificity across levels of analysis: behaviour (PDM accuracy reduction only), computational (boundary reduction only in PDM; no drift change), BOLD (reduced left-SFS accumulated-evidence signal for PDM but not VDM; Fig. 4a–c), and functional coupling (SFS–occipital PPI increase during PDM only; Fig. 5).

· Matched stimuli and motor outputs across tasks, so any peripheral sensations or general arousal effects should have influenced both tasks similarly; they did not.

Together, these converging task-selective effects reduce the likelihood that the results reflect non-specific stimulation or time-on-task. We will add an explicit statement in the Limitations noting the absence of sham/control and outlining it as a priority for future work.

(3.3) No a priori power analysis is presented.

We appreciate this point. Our sample size (n = 20) matched prior causal TMS and combined TMS–fMRI studies using similar paradigms and analyses (e.g., Philiastides et al., 2011; Rahnev et al., 2016; Jackson et al., 2021; van der Plas et al., 2021; Murd et al., 2021), and was chosen a priori on that basis and the practical constraints of cTBS + fMRI. The within-subject DID approach and hierarchical modelling further improve efficiency by leveraging all trials.

To address the reviewer’s request for transparency, we will (i) state this rationale in Methods—Participants, and (ii) ensure that all primary effects are reported with 95% CIs or posterior probabilities (already provided for the HDDM as pmcmcp_{\mathrm{mcmc}}pmcmc). We also note that the design was sensitive enough to detect RT changes in both tasks and a selective accuracy change in PDM, arguing against a blanket lack of power as an explanation for null VDM accuracy effects. We will nevertheless flag the absence of a formal prospective power analysis in the Limitations.

Recommendations for the Authors:

Reviewer #1 (Recommendations For The Authors):

Some important elements of the methods are missing. How was the site for targeting the SFS with TMS identified? The methods described how M1 was located but not SFS.

Thank you for catching this omission. In the revised Methods we explicitly describe how the left SFS target was localized. Briefly, we used each participant’s T1-weighted anatomical scan and frameless neuronavigation to place a 10-mm sphere at the a priori MNI coordinates (x = −24, y = 24, z = 36) derived from prior work (Heekeren et al., 2004; Philiastides et al., 2011). This sphere was transformed to native space for each participant. The coil was positioned tangentially with the handle pointing posterior-lateral, and coil placement was continuously monitored with neuronavigation throughout stimulation. (All of these procedures mirror what we already report for M1 and are now stated for SFS as well.)

Where to revise the manuscript:

Methods → Stimulation protocol. After the first sentence naming cTBS, insert:<br /> “The left SFS target was localized on each participant’s T1-weighted anatomical image using frameless neuronavigation. A 10-mm radius sphere was centered at the a priori MNI coordinates x = −24, y = 24, z = 36 (Heekeren et al., 2004; Philiastides et al., 2011), then transformed to native space. The MR-compatible figure-of-eight coil was positioned tangentially over the target with the handle oriented posterior-laterally, and its position was tracked and maintained with neuronavigation during stimulation.”

It is not clear how participants were instructed that they should perform the value-difference task. Were they told that they should choose based on their original item value ratings or was it left up to them?

We agree the instruction should be explicit. Participants were told_: “In value-based blocks, choose the item you would prefer to eat at the end of the experiment.”_ They were informed that one VDM trial would be randomly selected for actual consumption, ensuring incentive-compatibility. We did not ask them to recall or follow their earlier ratings; those ratings were used only to construct evidence (value difference) and to define choice consistency offline.

Where to revise the manuscript:

Methods → Experimental paradigm.

Add a sentence to the VDM instruction paragraph:

“In value-based (LIKE) blocks, participants were instructed to choose the item they would prefer to consume at the end of the experiment; one VDM trial was randomly selected and implemented, making choices incentive-compatible. Prior ratings were used solely to construct value-difference evidence and to score choice consistency; participants were not asked to recall or match their earlier ratings.”

Line 86 Introduction, some previous studies were conducted on animals. Why it is problematic that the studies were conducted in animals is not stated. I assume the authors mean that we do not know if their findings will translate to the human brain? I think in fairness to those working with animals it might be worth an extra sentence to briefly expand on this point.

We appreciate this and will clarify that animal work is invaluable for circuit-level causality, but species differences and putative non-homologous areas (e.g., human SFS vs. rodent FOF) limit direct translation. Our point is not that animal studies are problematic, but that establishing causal roles in humans remains necessary.

Revision:

Introduction (paragraph discussing prior animal work). Replace the current sentence beginning “However, prior studies were largely correlational”

“Animal studies provide critical causal insights, yet direct translation to humans can be limited by species-specific anatomy and potential non-homologies (e.g., human SFS vs. frontal orienting fields in rodents). Therefore, establishing causal contributions in the human brain remains essential.”

Line 100-101: "or whether its involvement is peripheral and merely functionally supporting a larger system" - it is not clear what you mean by 'supporting a larger system'

We meant that observed SFS activity might reflect upstream/downstream support processes (e.g., attentional control or working-memory maintenance) rather than the computation of evidence accumulation itself. We have rephrased to avoid ambiguity.

Revision:

Introduction. Replace the phrase with:

“or whether its observed activity reflects upstream or downstream support processes (e.g., attention or working-memory maintenance) rather than the accumulation computation per se.”

The authors do have to make certain assumptions about the BOLD patterns that would be expected of an evidence accumulation region. These assumptions are reasonable and have been adopted in several previous neuroimaging studies. Nevertheless, it should be acknowledged that alternative possibilities exist and this is an inevitable limitation of using fMRI to study decision making. For example, if it turns out that participants collapse their boundaries as time elapses, then the assumption that trials with weaker evidence should have larger BOLD responses may not hold - the effect of more prolonged activity could be cancelled out by the lower boundaries. Again, I think this is just a limitation that could be acknowledged in the Discussion, my opinion is that this is the best effort yet to identify choice-relevant regions with fMRI and the authors deserve much credit for their rigorous approach.

Agreed. We already ground our BOLD regressors in the DDM literature, but acknowledge that alternative mechanisms (e.g., time-dependent boundaries) can alter expected BOLD–evidence relations. We now add a short limitation paragraph stating this explicitly.

Revision:

Discussion (limitations paragraph). Add:

“Our fMRI inferences rest on model-based assumptions linking accumulated evidence to BOLD amplitude. Alternative mechanisms—such as time-dependent (collapsing) boundaries—could attenuate the prediction that weaker-evidence trials yield longer accumulation and larger BOLD signals. While our behavioural and neural results converge under the DDM framework, we acknowledge this as a general limitation of model-based fMRI.”

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations For The Authors):

Minor points

I suggest the proportion of missed trials should be reported.

Thank you for the suggestion. In our preprocessing we excluded trials with no response within the task’s response window and any trials failing a priori validity checks. Because non-response trials contain neither a choice nor an RT, they are not entered into the DDM fits or the fMRI GLMs and, by design, carry no weight in the reported results. To keep the focus on the data that informed all analyses, we now (i) state the trial-inclusion criteria explicitly and (ii) report the number of analysed (valid) trials per task and run. This conveys the effective sample size contributing to each condition without altering the analysis set.

Revision:

Methods → (at the end of “Experimental paradigm”): “Analyses were conducted on valid trials only, defined as trials with a registered response within the task’s response window and passing pre-specified validity checks; trials without a response were excluded and not analysed.”

Results → “Behaviour: validity of task-relevant pre-requisites” (add one sentence at the end of the first paragraph): “All behavioural and fMRI analyses were performed on valid trials only (see Methods for inclusion criteria).”

Figure 4 c is very confusing. Is the legend or caption backwards?

Thanks for flagging. We corrected the Figure 4c caption to match the colouring and contrasts used in the panel (perceptual = blue/green overlays; value-based = orange/red; ‘post–pre’ contrasts explicitly labeled). No data or analyses were changed, just the wording to remove ambiguity.

Revision:

Figure 4 caption (panel c sentence). Replace with:

“(c) Post–pre contrasts for the trialwise accumulated-evidence regressor show reduced left-SFS BOLD during perceptual decisions (green overlay), with a significantly stronger reduction for perceptual vs value-based decisions (blue overlay). No reduction is observed for value-based decisions.”

Even if not statistically significant it may be of interest to add the results for Value-based decision making on SFS in Supplementary Table 3.

Done. We now include the SFS small-volume results for VDM (trialwise accumulated-evidence regressor) alongside the PDM values in the same table, with exact peak, cluster size, and statistics.

Revision:

Supplementary Table 3 (title):

“Regions encoding trialwise accumulated evidence (parametric modulation) during perceptual and value-based decisions, including SFS SVC results for both tasks.”

Model comparisons: please explain how model complexity is accounted for.

We clarify that model evidence was compared using the Deviance Information Criterion (DIC), which penalizes model fit by an effective number of parameters (pD). Lower DIC indicates better out-of-sample predictive performance after accounting for model complexity.

Revision:

Methods → Hierarchical Bayesian neural-DDM (last paragraph). Add:

“Model comparison used the Deviance Information Criterion (DIC = D̄ + pD), where pD is the effective number of parameters; thus DIC penalizes model complexity. Lower DIC denotes better predictive accuracy after accounting for complexity.”

Reviewer #3 (Recommendations For The Authors):

The following issues would benefit from clarification in the manuscript:

- It is stated that "Our sample size is well within acceptable range, similar to that of previous TMS studies." The sample size being similar to previous studies does not mean it is within an acceptable range. Whether the sample size is acceptable or not depends on the expected effect size. It is perfectly possible that the previous studies cited were all underpowered. What implications might the lack of an a priori power analysis have for the interpretation of the results?

We agree and have revised our wording. We did not conduct an a priori power analysis. Instead, we relied on a within-participant design that typically yields higher sensitivity in TMS–fMRI settings and on convergence across behavioural, computational, and neural measures. We now acknowledge that the absence of formal power calculations limits claims about small effects (particularly for null findings in VDM), and we frame those null results cautiously.

Revision:

Discussion (limitations). Add:

“The within-participant design enhances statistical sensitivity, yet the absence of an a priori power analysis constrains our ability to rule out small effects, particularly for null results in VDM.”

- I was confused when trying to match the results described in the 'Behaviour: validity of task-relevant pre-requisites' section on page 6 to what is presented in Figure 1. Specifically, Figure 1C is cited 4 times but I believe two of these should be citing Figure 1B?

Thank you—this was a citation mix-up. The two places that referenced “Fig. 1C” but described accuracy should in fact point to Fig. 1B. We corrected both citations.

Revision:

Results → Behaviour: validity… Change the two incorrect “Fig. 1C” references (when describing accuracy) to “Fig. 1B”.

- Also, where is the 'SD' coefficient of -0.254 (p-value = 0.123) coming from in line 211? I can't match this to the figure.

This was a typographical error in an earlier draft. The correct coefficients are those shown in the figure and reported elsewhere in the text (evidence-specific effects: for PDM RTs, SD β = −0.057, p < 0.001; for VDM RTs, VD β = −0.016, p = 0.011; non-relevant evidence terms are n.s.). We removed the erroneous value.

Revision:

Results → Behaviour: validity… (sentence with −0.254). Delete the incorrect value and retain the evidence-specific coefficients consistent with Fig. 1B–C.

- It is reported that reaction times were significantly faster for the perceptual relative to the value-based decision task. Was overall accuracy also significantly different between the two tasks? It appears from Figure 3 that it might be, But I couldn't find this reported in the text.

To avoid conflating task with evidence composition, we did not emphasize between-task accuracy averages. Our primary tests examine evidence-specific effects and TMS-induced changes within task. For completeness, we now report descriptive mean accuracies by task and point readers to the figure panels that display accuracy as a function of evidence (which is the meaningful comparison in our matched-evidence design). We refrain from additional hypothesis testing here to keep the analyses aligned with our preregistered focus.

Revision:

Results → Behaviour: validity… Add:

“For completeness, group-mean accuracies by task are provided descriptively in Fig. 3a; inferential tests in the manuscript focus on evidence-specific effects and TMS-induced changes within task.”

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Lack of Sensitivity Analyses for some Key Methodological Decisions: Certain methodological choices in this manuscript diverge from approaches used in previous works. In these cases, I recommend the following: (i) The authors could provide a clear and detailed justification for these deviations from established methods, and (ii) supplementary sensitivity analyses could be included to ensure the robustness of the findings, demonstrating that the results are not driven primarily by these methodological changes. Below, I outline the main areas where such evaluations are needed:

This detailed guidance is incredibly valuable, and we are grateful. Work of this kind is in its relative infancy, and there are so many design choices depending on the data available, questions being addressed, and so on. Help us navigate that has been extremely useful. In our revised manuscript we are very happy to add additional justification for design choices made, and wherever possible test the impact of those choices. It is certainly the case that different approaches have been used across the handful of papers published in this space, and, unlike in other areas of systems neuroscience, we have yet to reach the point where any of these approaches are established. We agree with the reviewer that wherever possible these design choices should be tested.

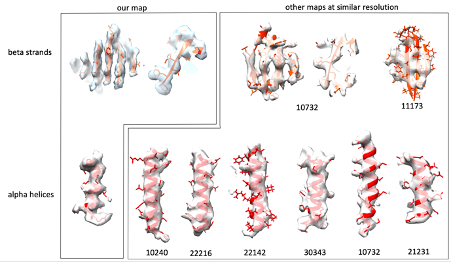

Use of Communicability Matrices for Structural Connectivity Gradients: The authors chose to construct structural connectivity gradients using communicability matrices, arguing that diffusion map embedding "requires a smooth, fully connected matrix." However, by definition, the creation of the affinity matrix already involves smoothing and ensures full connectedness. I recommend that the authors include an analysis of what happens when the communicability matrix step is omitted. This sensitivity test is crucial, as it would help determine whether the main findings hold under a simpler construction of the affinity matrix. If the results significantly change, it could indicate that the observations are sensitive to this design choice, thereby raising concerns about the robustness of the conclusions. Additionally, if the concern is related to the large range of weights in the raw structural connectivity (SC) matrix, a more conventional approach is to apply a log-transformation to the SC weights (e.g., log(1+𝑆𝐶<sub>𝑖𝑗</sub>)), which may yield a more reliable affinity matrix without the need for communicability measures.

The reason we used communicability is indeed partly because we wanted to guarantee a smooth fully connected matrix, but also because our end goal for this project was to explore structure-function coupling in these low-dimensional manifolds. Structural communicability – like standard metrics of functional connectivity – includes both direct and indirect pathways, whereas streamline counts only capture direct communication. In essence we wanted to capture not only how information might be routed from one location to another, but also the more likely situation in which information propagates through the system.

In the revised manuscript we have given a clearer justification for why we wanted to use communicability as our structural measure (Page 4, Line 179):

“To capture both direct and indirect paths of connectivity and communication, we generated weighted communicability matrices using SIFT2-weighted fibre bundle capacity (FBC). These communicability matrices reflect a graph theory measure of information transfer previously shown to maximally predict functional connectivity (Esfahlani et al., 2022; Seguin et al., 2022). This also foreshadowed our structure-function coupling analyses, whereby network communication models have been shown to increase coupling strength relative to streamline counts (Seguin et al., 2020)”.

We have also referred the reader to a new section of the Results that includes the structural gradients based on the streamline counts (Page 7, line 316):

“Finally, as a sensitivity analysis, to determine the effect of communicability on the gradients, we derived affinity matrices for both datasets using a simpler measure: the log of raw streamline counts. The first 3 components derived from streamline counts compared to communicability were highly consistent across both NKI (r<sub>s</sub> = 0.791, r<sub>s</sub> = 0.866, r<sub>s</sub> = 0.761) and the referred subset of CALM (r<sub>s</sub> = 0.951, r<sub>s</sub> = 0.809, r<sub>s</sub> = 0.861), suggesting that in practice the organisational gradients are highly similar regardless of the SC metric used to construct the affinity matrices”.

Methodological ambiguity/lack of clarity in the description of certain evaluation steps: Some aspects of the manuscript’s methodological description are ambiguous, making it challenging for future readers to fully reproduce the analyses based on the information provided. I believe the following sections would benefit from additional detail and clarification:

Computation of Manifold Eccentricity: The description of how eccentricity was computed (both in the results and methods sections) is unclear and may be problematic. The main ambiguity lies in how the group manifold origin was defined or computed. (1) In the results section, it appears that separate manifold origins were calculated for the NKI and CALM groups, suggesting a dataset-specific approach. (2) Conversely, the methods section implies that a single manifold origin was obtained by somehow combining the group origins across the three datasets, which seems contradictory. Moreover, including neurodivergent individuals in defining the central group manifold origin in conceptually problematic. Given that neurodivergent participants might exhibit atypical brain organization, as suggested by Figure 1, this inclusion could skew the definition of what should represent a typical or normative brain manifold. A more appropriate approach might involve constructing the group manifold origin using only the neurotypical participants from both the NKI and CALM datasets. Given the reported similarity between group-level manifolds of neurotypical individuals in CALM and NKI, it would be reasonable to expect that this combined origin should be close to the origin computed within neurotypical samples of either NKI or CALM. As a sanity check, I recommend reporting the distance of the combined neurotypical manifold origin to the centres of the neurotypical manifolds in each dataset. Moreover, if the manifold origin was constructed while utilizing all samples (including neurodivergent samples) I think this needs to be reconsidered.