- Aug 2018

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

Whilst social theorists are no longer united in the belief that all time systems are reducible to the functional need of human synchro~is_ation and co-ordination they seem to have little doubt about the validity of Sorokin and Merton's other key point that, unlike social time, the time of nature is that of the clock, a time characterised by invariance and quantity. Despite significant shifts in the understanding of social time, the assumptions about nature, natural time, and the subject matter of the natural sciences have remained largely unchanged.

Adam argues here that while the concept of "social time" has evolved, social scientists' ideas around "natural time" have not kept pace with new scientific research, and incorrectly continue to be described as constant and quantitative (aka clock time).

Further, "natural time" incorrectly incorporates other temporal experiences and seems to be used as a convenient counter foil to "social time"

-

Explored in these multiple expressions, time emerged as a fundamentally transdisciplinary subject and necessitated an understanding that is no longer containable within the traditional assumptions and categories of social science. We now need to reflect on the implications of these findings for social theory. This entails refocusing on some issues and re-assessing a few of the classical social theory traditions in the light of our findings. It requires that we spell out the limitations of the classical practice of abstraction and dualistic theorising for an understanding of 'social time' and that we question the tradition of claiming time exclusively for the human realm by locating it in mind, language or the functional needs of social organisation. This involves us in a re-evaluation of the dualistic conceptualisation of natural and social time and the closely related idea that all time is social time. It necessitates further that we explore the role of metaphors and focus explicitly on the social science convention of limiting the time-span of concern to a few hundred years

Adam describes time as a transdisciplinary subject and challenges the notion that time is entirely socially constructed. She tends to consider natural- and physics-conceptions of time, along side social theory.

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

phase-angle differences simply refer to whether the phases, the parts of one rhythmic pattern,

Phase-angle definition.

"phase-angle differences simply refer to whether the phases, the parts of one rhythmic pattern, lag, precede, or coincide with those of another."

-

Flaherty’s data and theory indicate that rather than the amount and nature of the objective experiences in a situation, what makes time seem to pass extra slowly or quickly is the extent to which the individual engages in conscious information processing during the time. When the amount of conscious information processing is about average for the individual, the individual experiences time as passing at what that individual has come to perceive as the usual rate, but when the amount of such processing is high, time appears to slow down (protracted duration); when such information processing is low, time appears to speed up (temporal compression)

The experience of time passing (fast or slow) is related to conscious information processing.

-

“Since one cannot distinguish a figure without a background, the present does not meaningfully exist without a past” (emphasis added; 2001, p. 608). As the background, the past provides a benchmark for the present against which comparisons can be made. And such comparisons indicate whether the present is the same as the past or different from it.

Relationship between present and past for sensemaking and meaning.

Later Bluedorn notes that interpretation and understanding of the past can be applied to a similar present. If they are different, then "the past provides a context, a frame for the present, and the linkages with the past provide an explanation for the present by suggesting how the present came to be, which makes the present more understandable, more meaningful."

The question then becomes which past -- how long ago (its temporal depth) is compared to the present (or future) for sensemaking.

-

the idea of entrainment presented in Chapter 6—the adjustment of the pace or cycle of an activity to match or synchronize with that of another activity (Ancona and Chong 1996, p. 253)—does suggest a reason why faster could be better, but it also suggests that faster could be worse.

Entrainment definition.

"This, as the entrainment phenomenon and examples illustrate, supports the contingency view of speed, that the appropriate speed varies by activity and context." (p. 190)

-

So connections and the meaning they generate are fundaThe Best of Times and the Worst of Timesmental, which is why the loss of meaning is so troubling—the systematic loss of meaning even more so.

Fundamental temporality of connections definition.

How two factors -- speed/tempo and temporal depth of an experience generate meaning.

-

Put succinctly, these principles indicate that the definition of the situation guides human behavior, and according to the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis, language is a necessary prerequisite for defining any situation (see Chapter 1). Language provides the elements from which meaning is constructed—the names of things and their qualities and the manner in which they may be related—and the definition of the situation combines these elements to construct sense-making explanations of events, definitions of the situation.

Sensemaking is linked to language. If an event/thing cannot be defined then it can't be acted upon, discerned or generate motives.

-

Lewin’s famous final clause, “there is nothing so practical as a good theory,” means that understanding (theory) can guide useful action (the practical), so theory (understanding) can be empowering. A lack of meaning and understanding of events also makes it very hard to know what one should do (norm- lessness or anomie), because it is nearly impossible to know what to do in a situation if one cannot comprehend it.

One example of meaning/alienation is a lack of understanding which interrupts sensemaking and creates a sense of friction in how to react/behave.

-

“the dynamic weaving of events, interactions, situations, and phases that comprise those relationships” (2000, p. 27), the dynamic weaving of events, interactions, and situations being very similar to narrative.

Temporal context definition.

Furthers the notion of narrative and how relationships between events/things is transformed into a cohesive whole which is necessary for sensemaking.

-

A narrative consists of three essential elements: past events, story elements, and a temporal ordering (Maines 1993, p. 21).

Narrative definition.

Developing the plot around the story elements is the most important element for sensemaking. It transforms a chronology/sequence of events into something more meaningful, more memorable,and more relatable.

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

Personal and organizational histories occupy prominent figure positions in the figure-ground dichotomy, and that such histories are used to cope with the future is indicated by several pieces of evidence.

Does this help to explain the need for SBTF volunteers to situate themselves in time -- as a way to construct a history in Weick's "figure-ground construction" method of sensemaking for themselves and to that convey sense to others?

-

Temporal focus is the degree of emphasis on the past, present, and future (Bluedorn 2000e, p. 124).

Temporal focus definition. Like temporal depth, both are socially constructed.

Cites Lewin (time perspective) and Zimbardo & Boyd.

-

The results presented in Bluedorn (2000e) and the Appendix consistently support the distinction between temporal depth and temporal focus. Conceptually the two terms refer to different phenomena, and empirical measures of the two share so little variance in common that for practical purposes they can be regarded as orthogonal. Temporal depth is the distance looked into past and

Differences between temporal depth vs temporal focus are orthogonal -- two separate conceptual ideas and refer to different phenomena.

Depth = "distance looked into the past and future" Focus = "importance attached to the past, present and future"

-

However, Boyd and Zimbardo’s interest was not in comparing short-, mid-, and long-term temporal depths; rather, it was in examining the degree to which people were oriented to a transcendental future, and in examining the extent to which this variation covaried with other factors such as age, gender, and ethnicity. This is a natural extension of the questions involved in research on general past, present, and future temporal orientations (e.g., Kluck- hohn and Strodtbeck 1961, pp. 13-15), orientations that at first glance appear similar to issues of temporal depth. However, as I have argued elsewhere in opposing the use of the temporal orientation label, these general orientations are more an issue of the general temporal direction or domain that an individual or group may emphasize (Bluedorn 2000e) than the distance into each that the individual or group typically uses. The latter is the issue of temporal depth; the former, what I have called temporal focus (Bluedorn 2000e)

Comparison of Bluedorn's thinking about temporal depth vs temporal focus instead of framing it as a temporal orientation (the direction/domain that an individual or group emphasizes in sensemaking).

ZImbardo and Boyd use the phrase "time perspective" rather than temporal orientation

-

And if Weick has drawn the correct conclusion about how the past is used to enact the present, being able to note the differences may be even more important than being able to see the similarities. This is especially so in equivocal enactments, which Weick (1979, p. 201) described as involving a figure-ground construction, one in which the ground consists of the strange and unfamiliar

Weick describes the need to discern differences over similarities to effectively use past-present metaphors as a sense-making device.

-

Among the reasons this may be so is that the simple future tense is more open-ended than the future perfect tense, the latter seeming to convey a sense of closure and a focus on specific events, which is unlike the simple future tense in which anything is possible (Weick 1979, pp. 198-99). It is well to note that although Weick did not explicitly frame his argument in terms of metaphor, it is really another example of the past-as-metaphor-for- the-future idea developed in this chapter, albeit a more precise manifestation of it. The precision comes in Weick’s conclusion that some futures are more like the past, are more similar to it than others. In his argument, the future described in future perfect terms is more similar to the past than the future described in simple future terms.

future perfect tense appears to generate a sense of focus and closure while simple future tense is more open-ended.

Weick theorizes that future perfect tense casts the description of a future event in more detail.

-

To consider the future, it may help to treat it like the past, that is, as ifit had already happened. This is the premise Weick proposed in his discussion of future perfect thinking (1979, pp. 195-200). Future perfect thinking is a grammatical prescription instructing managers and planners and all who consider the future to do so in the future perfect tense. Thus rather than the simple future tense as used in a statement like “We shall overcome,” the future perfect128Eternal Horizonstense would have us say, “We shall have overcome.” Alfred Schutz believed that the “planned act bears the temporal character of pastness' (Schutzs emphasis), because the actor projects the act as completed and in the past, a paradox that places the act in both the past and the future at the same time, something the future perfect tense makes possible (1967, p. 61). These were insights that Weick both noted (1979, p. 198) and built upon to explain why future perfect thinking may make it easier to envision possible futures.

Interesting proposal to use future perfect tense to envision the future.

is that happening to an extent with the multiple uses/tenses of "update" in the SBTF transcripts?

-

Weick argued that the past was used to understand the present and the future, that neither could be understood without the past. And how the past can provide this understanding, this meaning, is a major insight

Weick connects sensemaking in present and future constructs to retrospection of the past.

See also: Fraisse (1963, p. 172) and Schutz (1967, p. 51)

-

Unfortunately, the similarities, the likenesses, may overwhelm the differences (see Morgan 1997, pp. 4-5). And according to Weick, “people who select interpretations for present enactments usually see in the present what they’ve seen before” (1979, p. 201). In terms of the past-as-metaphor perspective developed in this chapter, “what they’ve seen before” implies the use of “an eye for resemblances,” the ability to see the similarities. But as Aristotle, Morgan, and Neustadt and May all noted, there is more to the mature use of metaphor than detecting the similarities between events and situations; the differences matter too. They matter, in part, because the ability to detect and deal with novelty may be a key to both organizational learning and performance (Butler т995> PP· 944-46)

Using the past to metaphorically describe the present.

-

And the determination of organizational age illustrates the constructed, enacted nature of the past, because what at first glance seems like a simple, even objective matter becomes ambiguous when mergers and acquisitions are involved. Is the founding date the date that the oldest of the merger partners began operations, or is it the date when the last partners merged? Families can face the same ambiguities when one or both spouses have been married previously and they and their children combine to form new families. As the definition of the situation principle teaches (see Chapter 1), the important issue is when the people in the organization or family believe it was founded.

Ambiguity about "founding date" of a merged organization is akin to the friction point for SBTF data collection -- is the date/timestamp the original social media post or the shared post (either of which may occur at different points in the stream). What is the boundary?

-

the past generally being ignored in organization science (for exceptions, see March 1999; Thoms and Greenberger 1995; Webber 1972; and others cited later in the chapter), not that the rest of the social sciences are much less deficient in this regard (see Zimbardo and Boyd 1999, p. 1272).

Contested area of study -- organizational science and other social sciences typically don't study the past.

-

Steve Ferris and I found that organizational age was positively correlated with both past and future temporal depths, and that these relationships persisted after controlling for several organizational and environmental variables (Bluedorn and Ferris 2000). The older the organization, the further its members looked into both the past and the future, and the positive temporal depth correlations with the organization’s age may suggest why

Bluedorn argues that "organizational past apparently becomes received history" which is also socially constructed, interpreted and potentially inaccurate.

Having a longer history provides an organization with a longer timescape to imagine its past and future.

-

The past leads to and influences the future, but the future does not influence the past.Thus El Sawy s research provided a second clue that past and future are related, and it even added a causal direction (i.e., “A connection to the past facilitates a connection to the future” [March 1999, p. 75])·

Study demonstrates "time's arrow" that the past influences future but not the other way around.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arrow_of_time

This idea also contributes to a spatial sense of time in Western cultures as "behind", "forward", "ahead", etc. Eastern and Global South cultures do not share this spatial representation.

-

the result is a statistically significant positive correlation (see the Appendix). The proposed connection is accurate: The longer the respondent’s past temporal depth, the longer the respondent’s future temporal depth.

Past temporal depth and future temporal depth are positively connected. The longer the past perception, the longer the future perception.

This is true for both individuals and groups.

-

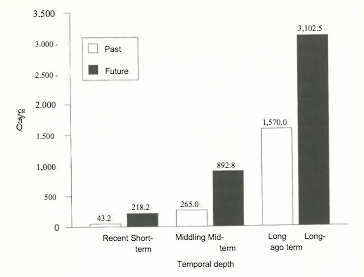

Perhaps the most noteworthy of the differences is that each of the future regions extends much further into the future than their past counterparts extend into the past. The short-term future extends about five times further than does the recent past; the mid-term future, about three-and-one-third times as far as the middling past; and the longterm future, about twice as far as the long-ago past. So although the steplike pattern is similar for both the past and future regions, the future depths extend over substantially larger amounts of time than do those in the past

Comparing respondents' differences in temporal depth of past vs future. A person's perception of future is considerably longer than their perception of the past.

-

the temporal distances into the past and future that individuals and collectivities typically consider when contemplating events that havehappened, may have happened, or may happen.

Temporal depth definition -- applies to individuals as well as groups.

It considers time in two directions (past and future)

-

- Jul 2018

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

Drawing on the theory of distributed cognition [5], we utilizerepresentational physical artifacts to provide a tangible interface for task planning, aural cues for time passage, and an ambient, glanceable display to convey status

Is there a way to integrate dCog and a more sociotemporal theory, like Zimbardo & Boyd's Time Perspective Theory or some of Adam's work on timescapes?

-

Since time elapses in a linear fashion and users may switch between tasks during the course of a day, the “elapsed” marbles roll into a track below the storage cylinders.

This is a Western, industrialized perspective of temporal experience and is not universal.

Wonder how users respond to the marble representation/metaphor -- does this intuitively make sense to them?

-

The design principle of the Time Machinefollows the stage-based model of personal informatics systems proposed by Li, Dey and Forlizzi

Not familiar with this design model. Wonder if a participatory or design thinking approach is or can be intergrated?

-

Figure 2. The stage-based model of personal informatics systems (after [6]).

Helpful diagram to describe stage-based model design.

-

We have introduced a novel approach to time management using a device embodying characteristics of both an ambient display and a tangible user interface.

Will be interesting to see the results of the field studies to better understand whether making time materially tangible fits the mental scheme for users. And whether their relationship with task/time management improves or causes new levels of friction.

-

Thus, people have historically relied on visual or auditory signals to estimate, determine, or track time. Initially, these time signals were derived from nature: theposition of the sun in the sky orthe sound of a rooster in the morning. Eventually, these time signals became technology-based. Many people now rely on displays, or signals, of time that derive from our world of pervasive devices: digital time displayed on a device screen, a notification sound from a calendar application.

Curious why temporal semiotics (see Zerubavel) is not mentioned here.

-

Because time is not physical, the human perception of time is subjective: the passage of time can seem slower or faster depending on factors liketask

gets at the experience of "flow" (See Csikszentmihalyi)

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

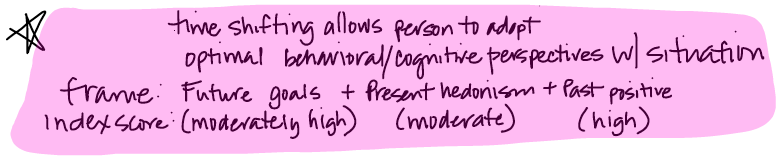

This conjecture leads us to promote the ideal of a “balanced TP” as most psycho-logically and physically healthy for individuals and optimal for societal functioning. Balance is defi ned as the mental ability to switch fl exibly among TPs depending on task features, situational considerations, and personal resources rather than be biased toward a specifi c TP that is not adaptive across situations. The future focus gives people wings to soar to new heights of achievement, the past (positive) focus establishes their roots with tradition and grounds their sense of personal identity, and the present (hedonistic) focus nourishes their daily lives with the playfulness of youth and the joys of sensuality. People need all of them harmoniously operating to realize fully their human potential.

Balanced time perspective definition. Later called optimal time shifting in the Time Paradox book.

What are the heuristics and/or design implications for evoking more ideal time shifting behaviors and outcomes?

-

A further limitation of the generalizability of our scale may lie in its cultural relevance to individualist societies and their ambitions, tasks, and demands rather than to more collectivist, interdependent societies in which time is differently val-ued and conceptualized (Levine 1997 ). Obvious cross-cultural adaptations of the ZTPI are called for.

Acknowledged limitations in the original paper note that students may be more future oriented and the scale was predominantly tested on Western individualist cultures.

Later work has demonstrated that these concerns are not born out.

-

Our scale also has dem-onstrated predictive utility in experimental, correlational, and case study research.

The ZPTI is predictive of other psychological concepts -- emotional, behavioral, and cognitive -- that have temporal relationships.

Temporality is a rare psychological variable that can influence "powerful and pervasive impact" on individual behavior and societal activities.

-

The scale is based on theoretical reflection and analyses, interviews, focus groups, repeated factor analyses, feedback from experiment participants, discriminant validity analyses, and specifi c attempts to increase factor loadings and internal consistencies by item analyses and revisions.

Claims the ZPTI is both valid and reliable due to mixed-method empirical study and factor analysis to establish measurable constructs and consistency of findings.

-

State of Research on TP

Critique of previous research as overly simplified, one-dimensional (focused on future or present states, ignored past) and lack of reliable and valid measures for assessing time perspectives.

-

Thus, we conceive of TP as situationally determined and as a relatively stable individual-differences process.

Identifies time perspective as both a state and a trait. This fits with the idea that time perspective shifting is possible and preferred. The argument also supports the later empirical work that people are unaware of their time perspective and how it influences/biases their thinking and behavior (both positive as in goal setting, achievement, etc., and negative as in addiction, guilt, etc.)

-

Such limiting biases contrast with a “balanced time orientation,” an ideal-ized mental framework that allows individuals to fl exibly switch temporal frames among past, future, and present depending on situational demands, resource assess-ments, or personal and social appraisals. The behavior of those with such a time orientation would, on average, be determined by a compromise, or balancing, among the contents of meta-schematic representations of past experiences, present desires, and future consequences.

A temporal bias results from habitual overuse/underuse of past, present or future temporal frames.

Introduces the idea of optimal time shifting to incorporate various environmental forces.

-

In both cases, the abstract cognitive processes of reconstructing the past and constructing the future function to infl uence current decision making, enabling the person to transcend compelling stimulus forces in the immediate life space and to delay apparent sources of gratifi cation that might lead to undesirable con-sequences.

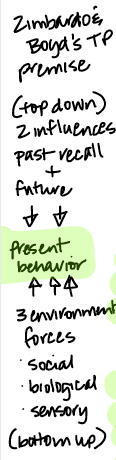

Core premise of Zimbardo and Boyd's time perspective theory diverges from Nuttin, Bandura and Carstensen's work.

Time Perspective Theory posits that dynamic influences on present behavior and cognition comes from top-down abstract (past/future) ideas and bottom-up environmental forces (social, biological, sensory).

-

More recently, Joseph Nuttin ( 1964 , 1985 ) supported the Lewinian time-fi lled life space, where “future and past events have an impact on present behavior to the extent that they are actually present on the cognitive level of behavioral functioning” ( 1985 , p. 54). Contemporary social–cognitive thinking, as represented in Albert Bandura’s ( 1997 ) self-effi cacy theory, advances a tripartite temporal infl uence on behavioral self-regulation as generated by effi cacy beliefs grounded in past experiences, current appraisals, and refl ections on future options. Behavioral gerontologist Laura Carstensen and her colleagues (Carstensen et al. 1999 ) have proposed that the perception of time plays a funda-mental role in the selection and pursuit of social goals, with important implications for emotion, cognition, and motivation.

Related work that builds on Lewin's premise:

Nuttin theorizes about the influence of past and future events on present behavior

Bandura's position supports his self-efficacy theory that temporal influences affect a person's innate ability to exert control over one's behavior in order to achieve goals.

Carstensen proposes that time perception influences choices, motives, and emotions about social goals.

-

TP is the often nonconscious process whereby the continual fl ows of personal and social experiences are assigned to tem-poral categories, or time frames, that help to give order, coherence, and meaning to those events.

Time perspective is an intuitive, unconscious process that people use for sensemaking in the present, recall of the past and to predict the future.

In this view, the present is concrete where past and future are abstract.

-

Lewin ( 1951 ) defi ned time perspective (TP) as “the totality of the individual’s views of his psychological future and psychological past existing at a given time” (p. 75).

Lewin defined time perspective.

Per Zimbardo/Boyd, Lewin's view incorporates a Zen-like present orientation that evokes a circular motion of time over the Western-centric linear/directional motion.

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

he two patterns—monochronic and polychronic—form a continuum, because polychronicity is the extent to which people prefer to engage in two or more tasks simultaneously, and the complete absence of any simultaneous involvements, engaging tasks one at a time, is the least polychronic position on the continuum.

Monochronic side of the continuum is linear

Polychronic side of the continuum is cyclical

Could Adam's timescape help to further describe this phenomenon? (see Perspectives on time: Zimabrdo + Adam slidedeck)

linear = spatial, historical, irreversible, tied to a beginning

cyclical = process, rhythmic, seasonal, bounded, sequential, hopeful (past+future+present)

-

The retention of “many problems in their minds simultaneously” speaks direcdy to the definition of polychronicity, mental activity being a component of polychronicity as well as overt behavior (Persing 1999)

Polychronicity is both a mental activity and overt behavior. It describes activity patterns.

Per Bluedorn, polychronicity is not multitasking which "combines speed and activity-pattern dimensions."

The dimensions include cognitive stages of processing, (task selection vs task performance), codes of processing (spatial vs linguistic), and modalities (audio vs visual). See Mark (2015) https://books.google.com/books?id=tq42DwAAQBAJ&pg=PT21&lpg=PT21&dq=bluedorn+multitasking&source=bl&ots=9ApyVTkXnI&sig=kwysyZ3eJp264Ngs57dUAV1Fy-o&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjL4MX53sXcAhViMH0KHU2LBscQ6AEwBnoECAYQAQ#v=onepage&q=bluedorn%20multitasking&f=false

-

Demographic Characteristics.

Mixed results for relationship between gender and polychronicity. No relationship between age and polychronicity. People with some formal higher education have higher degrees of polychronic attitudes and behaviors.

Perhaps because people with polychronic traits seek out higher ed?<br> Perhaps due to professional states that demand multiple tasks and/or speed.

-

Such questions not only point the direction for expanding our knowledge of polychronicity but also suggest the likelihood of various social and psychological determinants of it. One such determinant seems especially intriguing, and it is the individual’s breadth of attention. Breadth of attention is “the number and range of stimuli attended to at any one time” (Kasof 1997, p. 303). This concept is used to describe screeners, people who focus on a small range of stimuli and filter or “screen out” other stimuli. Conversely, nonscreeners attend to a large range of stimuli and are aware of a much larger range of potentially unrelated stimuli (Kasof 1997)

3rd wave: Is polychronicity related to "breadth of attention" -- or the ability to focus on multiple streams of thought/information while filtering/screening out distraction?

This idea would seems to have clear implications for SBTF social coordination work.

-

So does polychronicity scale? Or is it a nested phenomenon whereby someone might be monochronic within hour- long intervals but polychronic when the frame enlarges to a month? And if so, what might be the consequences of different nesting combinations?

3rd wave: Does polychronicity scale over time periods larger than a daily work setting? Does it change depending upon the temporal trajectory, rhythm, or horizon?

-

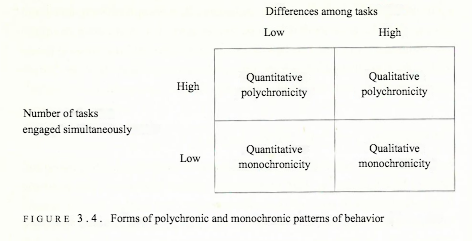

figure 3.4. Forms of polychronic and monochronic patterns of behavior

3rd wave:

Proposed new polychronicity typology that examines the difference between the types of tasks and the difference in the number of tasks.

Low/low = few tasks of similar type High/low = many tasks of different types High/high = many diverse tasks Low/high = few tasks of different types

Challenge with this type of analysis is that there are few (at least by 2002 publication date) task classifiers to qualitatively discern task differences. Bluedorn suggests potentially adapting a job characteristics/skill variety model -or- modifying a consumer products inventory of number/types of senses used (vision, hearing, tactile, etc.) as a skill variety attribute.

In SBTF's case, activations may be considered: High/Low (Quantitative polychronicity)

-

June Cotte and S. Ratneshwar (1999) have certainly documented the ability of some people to vary their behavior radically along the polychronicity continuum as they moved between work and leisure activities. Hall suggested the facility to make such shifts may be related to what he called a “high adaptive factor” (Bluedorn 1998, p. 114), such people being more flexible along the polychronicity continuum than others. In a life context of varying polychronicity demands, perhaps an individual whose own polychronicity lies near the average of the varying environmental demands might be able to cope most readily with them because the largest adjustment required would be smaller, hence less potentially uncomfortable or stressing than from any other position on the polychronicity continuum

3rd wave: Assuming polychronicity is a trait, are some people more adaptive to changes in polychronicity in different situations?

Does adaptability (or lack thereof) contribute to a friction point in work processes that could be modified to accommodate individual workers or organization values within the polychronic continuum?

-

Brown and Eisenhardt studied change and project management in computer firms and found that firms with less successful project portfolios demonstrated very low amounts of communication across projects. This was part of the context in which projects were planned, divided into small tasks, and then executed in a “structured sequence of steps” (1997, p. 14). A structured sequence is, of course, a monochronic strategy, and the low amount of communication is consistent with the proposition that monochronic strategies generate less awareness of other activities and tasks. One of the managers in their study remarked, “Most people only look at their part” (p. 14); another, “The work of everyone else doesn’t really affect my work” (p. 14). These responses contrasted with the pattern of work in the companies that managed their portfolios of projects more successfully, which Brown and Eisenhardt characterized as “iterative” (p. 14). Iterative (repetitive) patterns are suggestive of the back and forth flow of polychronic strategies

Iterative/repetitive work patterns suggest "back and forth flow of polychronic strategies."

Key point for SBTF social coordination: "At the less successful it was difficult to adjust projects in changing conditions because 'once started, the process took over.' It was hard to backtrack or reshape product specifications as circumstances changed."

Polychronic strategy: Higher level of willingness to adjust/correct work per feedback.

Monchronic strategy: Greater degree of satisificing in decision making.

-

Group Effectiveness

High group performance is related to moderate polychronicity in organizations with matrix structures (cross functional firms where an employee reports to multiple managers).

Organizations with greater speed in making strategic decisions, have higher performance in high tempo groups. Also, considering multiple options at the same time led to faster decisions.

Mixed results on relationships between polychronic values in a company and its financial performance.

-

So individual polychronicity is related to several individual variables. Relative to less polychronic people, more polychronic people appear to have more of the following:• Extraversión (extroversion)• Favorable inclination toward change• Tolerance of ambiguity• Formal education• Striving for achievement• Impatience and irritability• Frequency of lateness and absenteeismThose same people appear to have less of the following:• Conscientiousness• Stress (only in some jobs)But, as will be revealed in the following section, these are not the only individual variables to which individual polychronicity is related

Polychronic relationships with Individual traits.

-

Both studies reveal a positive correlation between polychronicity and speed values: The more polychronic the organization, the more doing things rapidly is valued in its culture. Although these consistent findings about the speed-polychronicity relationship support the explanation of the size- polychronicity relationship developed in this discussion, they are not a direct test of this explanation, which is, admittedly, speculative. More direct tests must await studies deliberately designed to investigate this explanation

Larger firms appear to more polychronic. That finding seems to follow Bluedorn's own speculative findings of a relationship between polychronic organizations and a culture that values speed (time compression).

Note: Organizational studies of polychronicity have been conducted through quantitative methods (surveys and questionnaires).

-

in a more polychronic culture, people would stand closer to each other while talking. So time and space are related in the social as well as the physical world.

Could the relationship between polychronicity and physical proximity help to explain the use of situated and/or spatial language in globalized, virtual social coordination work?

Note: National studies of polychronicity have been conducted through qualitative methods (observation and interviews)

-

At the level of individual beliefs and behavior, the nature of polychronicity as either a trait or a state becomes an important issue. Ifit is a trait, individuals will be much more consistent, even habitual, in the polychronicity process strategies they follow, more consistent than if polychronicity preferences are a state. But if polychronicity is a state, it will be affected much more by the contextual factors in an individual’s environment, leading to much greater variability in patterns of polychronicity behavior. So the degree of stability or its converse, the amount of variability, would provide important clues about polychronicity’s statelike or traitlike identity.

Later, Bluedorn notes other polychronicity studies that point to it being a more stable, habitual trait than a variable, contextual state.

-

At the group level—group referring to all potential culture-carrying aggregations larger than a single individual (e.g., departments, organizations, societies, etc.)—polychronicity is a value and belief complex that manifests itself in overt process strategies. Although the strength with which it is held may vary, as a fundamental process strategy—it is fair to say the fundamental process strategy—whichever position along the polychronicity continuum is normative in a culture is apt to be held strongly. This is because such process strategies are mainly learned unintentionally, usually unconsciously. Such learned knowledge is retained at the level of culture Edgar Schein (1992) labeled basic underlying assumptions. This deepest of cultural levels normally contains beliefs and values prescribing behaviors that are so taken for granted and institutionalized that they seldom rise to the conscious level for extensive examination and discussion (Schein 1992, p. 22). Consequently, they are difficult to change, and in this sense they are strongly held.

Is this due to LPP or some other cultural learning strategy?

-

From the beginning (Hall 1981b), polychronicity has been analyzed at both the group and individual levels. As such, it has been seen as both a cultural and an individual phenomenon. And values about the same phenomenon can and do occur in both cultures and personalities, but this does not mean that relationships involving them are the same across levels of analysis (e.g., Dansereau, Alutto, and Yammarino 1984; Robinson 1950). Relationships found at one level of analysis, individual or group, are suggestive of those relationships at another and are reasonable justifications for hypothesizing their existence as a prelude to their empirical investigation, such investigation clearly being necessary to establish the existence of relationships across multiple levels of analysis

Polychronicity can be studied across different levels of analysis -- individual and group.

This is important for establishing empirical research design and for confidence in understanding how relationships/variables occur across levels.

Critical piece for SBTF interview study to see how polychronicity is reflected in group and individuals.

-

Although it is easier to see this distinction in terms of a dichotomy—polychronic or monochronic—polychronicity is a variable that reflects an underlying continuum of engagement preferences and practices, and a potentially infinite set of gradations distinguish one individual’s preferences from another’s, as well as one culture’s from another’s

Polychronicity is not a binary state. It functions more as gradients within a "continuum of engagement preferences and practices" for both individuals and for work cultures.

The behavior and/or attitude is scored on a high (polychronic) or low (monochronic) scale.

-

Moreover, the correlations between the preference-for-engaging-two- or-more-events-simultaneously dimension and the other dimensions in the best-fitting model were very low, so Palmer and Schoorman concluded, “The three dimensions of time use preference [ preference-for-engaging-two-or- more-events-simultaneously], time tangibility, and context do not represent . highly correlated measures and should be considered separately” (1999, p. 336).

The more narrowly focused definition is better suited to empirical testing between polychronicity and other variables, such as context, etc.

Related work found low correlations between polychronicity and other time variables.

-

Following Bluedorn et al. (1999, p. 207) and Hall (Bluedorn 1998, p. no), polychronicity is the extent to which people (1) prefer to be engaged in two or more tasks or events simultaneously and are actually so engaged (the preference strongly implying the behavior and vice versa), and (2) believe their preference is the best way to do things.

Bluedorn's definition of polychronicity, originally described by Edward Hall in broader terms.

-

The “going back” is indicative of the back-and-forth pattern of polychronic behavior, because it is another way of engaging several activities during the same tim

use of spatial metaphor to describe polychronic behavior.

-

And although an infinite number of patterns are possible, all strategies for engaging life’s activities fall along a continuum known as polychronicity, a continuum describing the extent to which people engage themselves in two or more activities simultaneously. That this choice is fundamental is revealed by the fact that most people most of the time are unaware that they are even making it. This is because the choice of strategy results from a combination of culture and personality, both of which store these choices and preferences at deep levels, very deep levels. Nevertheless, a choice or a decision made unconsciously is still a choice or a decision

Decision strategies, like polychronicity, are often intuitive and unconscious.

Bluedorn mentions how culture and personality play a critical role in decision strategies. Potential intersection with Zimbardo's time perspective theory.

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

A concept in Anthony Giddens’s structuration theory explains how patterns like these are maintained with such regularity and precision. The concept is “duality of structure,” by which Giddens meant that “the structured properties of social systems are simultaneously the medium and outcome of social acts(Giddens’s emphasis; 1995, p· 19)·

Sensemaking wrt time can be explained through structuration theory. Cites Giddens' quoted definition.

Duality of structure applies to temporality when people follow rules/set patterns that in turn convey new socially constructed meanings.

I'm a little uncertain about this. Look at the Structuration Theory cheat sheet in Mendeley

-

Thus for meaning (significance) to be attributed to events, behaviors, and objects, to things in general, they must be seen in their relationships with other things. They can have no meaning as isolated phenomena.

Time generates meaning through comparison and relationships with other things.

For linear time, relationships between past, present and future provide for and universally communicate socially constructed meaning.

-

Barbara Adam said it well: “Much like people in their everyday lives, social scientists take time largely for granted. Time is such an obvious factor in social science that it is almost invisible” (1990, p. 3).

Cites Adam (1990).

Great quote for difficulty in communicating about time.

-

Less explicit and less emphasized in the literature is time’s role in the creation of meaning. Malinowski and Adam hint at this capability in their statements: “sentimental necessity,” “orientation,” and “symbol for the conceptual organisation of natural and social events,” the last of the three phrases most directly indicating time’s role in generating meaning. So both capabilities increase with the development of greater temporal expertise.

Homonid development: time as a tool for sensemaking.

Cites Adam (1990)

-

Bronislaw Malinowski addressed the functions of time as follows: “A system of reckoning time is a practical, as well as a sentimental, necessity in every culture, however simple. Members of every human group have the need of coordinating various activities, of fixing dates for the future, of placing reminiscences in the past, of gauging the length of bygone periods and of those to come” (1990, p. 203). Sixty-three years later Barbara Adam would state it thus: “As ordering principle, social tool for co-ordination, orientation, and regulation, as a symbol for the conceptual organisation of natural and social events, social scientists view time as constituted by social activity” (1990, p. 42).

Hominid development: time as a tool for social coordination.

Cites Adam (1990).

-

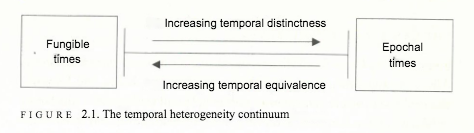

As with the geological epochs and archeological ages, human times become more epochal as they become more homogeneous within themselves and more differentiated from other periods, units, or types. In analysis of variance (anova) terms, the times become more epochal as the within-unit variance decreases and the between-type variance increases. Movement toward more epochal times is illustrated by phrases such as the “New York minute.” This metaphor for the fast pace of life in New York City (see Levine 1997; also see Chapter 4) is so effective because it violates a tacit understanding about minutes:

Epochs as ANOVA analogy. As the time becomes more distinct (increased between-unit variance and decreased within-unit variance), it resembles an epoch.

Epochs can also be described metaphorically.

Example: SBTF and "peace time"

-

Thinking in terms of degrees of difference rather than just two extremes allows more precise statements to be made about the form of time under consideration than if one’s conceptual portfolio contained only the two extreme forms

Continuum of temporal heterogeneity

-

Epochal time is defined by events. The time is in the events; the events do not occur in time. Events occurring in an independent time is the fungible time concept that Newton described so influentially as absolute time and Whitehead described so critically as a “metaphysical monstrosity.” When the time is in the event itself, the event defines the time. To take an everyday example, is it time for lunch or is it lunchtime?

Epochal time defined as in the event.

Whitehead: "Time is sheer succession of epochal durations" p. 32

-

I have written elsewhere that time “is a collective noun” (Bluedorn 2000e, p. 118). That pithy statement summed up the belief that there is more than one kind of time. For example, Paul Davies thought long and hard about time, especially as it is conceptualized in the physical sciences. Yet despite those labors, he felt time’s mystery still: “It is easy to conclude that something vital remains missing, some extra quality to time left out of the equations, or that there is more than one sort of time” (Davies’ emphasis; 1995, p. 17). So in the physical sciences just as in the social, the possibility is explicitly recognized that there may be more than one kind of time.

Good quote for CHI paper.

-

Several of the distinctions drawn by Joseph McGrath and Nancy Rotch- ford (1983, pp. 60-62) to describe the dominant concept of time held by Western industrialized societies in the twentieth century seem to describe this type of time well. This temporal form is homogeneous, which means that one temporal unit is the same as any other unit of the same type, and this means that such units are conceptually interchangeable with each other.

Fungible time defined as absolute, objective, uniform (consistant units), linear and that measures duration (Newton) and "without relation to anything external". Various authors have also described it as clock time, chronos, and abstract time.

Cites McGrath re: dominant Western industrialized time.

-

So the vital point is that all conceptions of time are and always will be social constructions, which is, in Barbara Adam’s words, “the idea that all time is social time” (1990, p. 42). After all, all human knowledge, including scientific knowledge, is socially constructed knowledge. But this point does not ipso facto invalidate any or all concepts of time. Their validity rests, instead, on their utility for various purposes, such as prediction and understanding. And as societies and cultures evolve, it is likely, perhaps even incumbent, for their concepts of time to evolve as well. So it would be well to understand how concepts of time differ in order to understand them and their differences better.

Time is a contested topic. Some believe time is binary, duality, or hierarchical and others (in physics, thermodynamics, metaphysics) propose that time flows in a particular direction.

Again cites Adam re: "all time is social time" and the need "to understand how concepts of time differ in order to understand them and their differences better."

-

Temporal RealitiesSome theorists have taken the multiple-types approach further and proposed multiple types of time that are arranged in hierarchies. It is interesting to note that these approaches all seem to rely on a hierarchical view of reality itself.

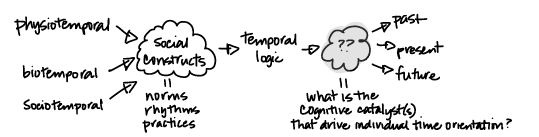

J.T. Fraser's more complex, hierarchical model of nested temporalities includes sociotemporality (time produced by social consensus) at the top.

The multiple, hierarchical views of time are most often rooted in biology and physics. Sociological and sociocultural theories of time embedded in hierarchies don't seem to have caught on. Other than Fraser, I haven't seen these mentioned elsewhere.

-

Another way of saying this is that there is no imperative to see such categories as mutually exclusive. Neither partner is the true, real, or even preferred time; instead, they may coexist, intermingle, and even be tightly integrated in specific social systems.

Critique of previous categorizations of time as dualities that "may coexist, intermingle and even by tightly integrated in specific social systems."

Cites Adam and Orlikowski/Yates here.

Also notes that clock-based and event-based time do coexist in organizations (Clark 1978, 1985).

-

a binary classification system exacerbates this tendency, with one choice receiving the imprimatur of “real time” and the alternative being condemned as a “perversion” of it, if it is perceived at all

Critique of previous categorizations of time as binary.

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

metaphor is a potentially powerful tool for understanding human beliefs and behavior, and the metaphors people hold about organizations (which encompass much of the way they define organizational reality) explain much about the decisions they make and the actions they take (see Morgan 1997, especially p. 4).

Background on the relationship between the origin of the escapement (device that powers gear movements of equal duration) in the mechanical clock and divine intervention >> "God set the clocks to ticking" (pg. 11).

Section describes the origins and importance of metaphor in temporal studies for understanding human beliefs, behavior, motives, and actions.

-

The possibility that time can explain other phenomena, especially human behavior, is the scientific raison d’être for studying time and caring about it: If times differ, different times should produce different effects. And an important mechanism through which differing times affect human behavior is thedefinition of the situation

Situational temporality is constructed through personal perceptions and interpretations which are further influenced by social interactions.

This is an important point to weave into the SBTF time study/social coordination paper. See also: Merton (1968) Social Theory and Social Structure.

-

Time is a social construction, or more properly, times are socially constructed, which means the concepts and values we hold about various times are the products of human interaction (Lauer 1981, p. 44). These social products and beliefs are generated in groups large and small, but it is not that simple. For contrary to Emile Durkheim’s assertion, not everyone in the group holds a common time, a time “such as it is objectively thought of by everybody in a single civilization” (1915, p. 10). This is so because in the perpetual structuration of social life (Giddens 1984) individuals bring their own interpretations to received social knowledge, and these interpretations add variance to the beliefs, perceptions, and values.

Social construction of time. The various definitions are nuanced according to the theorists' disciplines.

Giddens' work on structuration of social life and its effect on how individuals interpret received social knowledge is salient from Bluedorn's org studies perspective. Structuration offers less grounding when viewed through the lens of technology (see Orlikowski's 1992 critique in Mendeley).

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

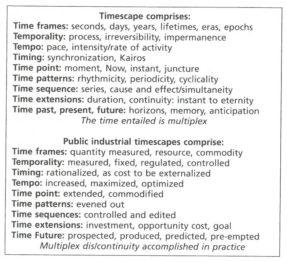

However, as Mark Poster points out, 'the new level of interconnectivity heightens the fragility of the social networks. '·50 The source of control now undermines its execution. For clock time to exist and thus to be measurable and controllable there has to be duration, an interval between two points in time. Without duration there is no before and after, no cause and effect, no stretch of time to be measured. The principles of instantaneity and simultaneity of action across space, as I have shown in chapter 3, are encountered in quantum physics; they have no place in the Newtonian world of causality and bodies in motion, the world chat we as embodied beings inhabit. The control of time that has reached the limit of compression has been shifted into a time world where notions of control are meaningless. More like the realm of myths and mysticism, the electronic world of interchangeable no-where and now-here requires knowledge and modes of being that are alien to the industrial way of life. Other modes of temporal existence, therefore, may hold some viral keys, their 'primitive' understanding of time pointing not ro control but to more appropriate ways of being in the realm of insrantaneity.

Adam argues that control of time is futile in an interconnected network where hyper-compression has effectively rendered duration/intervals of time as unmeasurable.

If temporality cannot be "measured, fixed, regulated or controlled" (see timescapes image), then time cannot be controlled.

Subsequently, we need other approaches to be "in the realm of instantaneity."

-

I propose that we think a bout temporal relations with reference to a cluster of temporal features, each implicated in all the others but not necessarily of equal importance in each instance. We might call this cluster a timescape. The notion of 'scape' is important here as it indicates, first, that time is inseparable from space and matter, and second, that context matters.

Definition of timescape -- "a cluster of temporal features, each implicated in all the others but not necessarily of equal importance in each instance."

-

This control clusrer of the five Cs of time, I have suggested, needs to be differentiated from both time tempering and transcendence, on the one hand, and time knowledge and know-how, on the other, since only in the control cluster is time objectified, externalized and constructed to specific design principles.

"... only in the control cluster is time objectified, externalized and constructed to specific design principles."

Tempering vs knowledge are also important distinctions for the SBTF time-study.

-

Once time is disembedded, that is, extracted from process and product, it becomes an object and as such subiect to bounding, exchange and transformation.40 It is in this form that time is colonized,, as distinct from the time embedded in events and processes, which has been subject ito cultural efforts of transcendence.

Check the citation. Don't understand this.

-

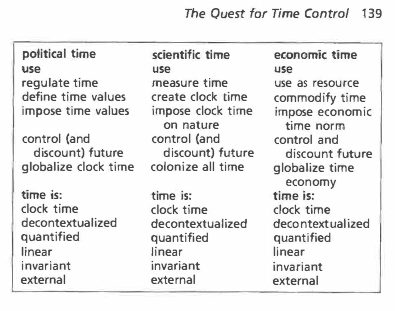

It shows thar irrespective of the diverse temporal uses of time in the political, scientific and economic spheres, a unified clock time underpins the differences in expressions. All other forms of temporal relations are refracted through chis created temporal form, or at least touched by its pervasive dominance

Clock-time dominates political, scientific and economic practices despite the very different ways temporality is represented in these fields.

-

This industrial norm, as I suggested above, is fundamentally rooted in clock time and underpinned by naturalized assumptions about not just the capacity but also the need to commodify, compress and control time.

-

There are two sides to the colonization of time: the global imposition of a particular kind of time which is colonization with time, and the social incursion into time -past and future, night-time and seasons, for example -which is the colonization of time. Colonization with time therefore refers to the export of clock and commodified time as unquestioned and unquestionable standard, colonization of time to the scientific, technological and economic reach into time -most usually of distant others who have no say in the matter.

Colonization with time is defined as exporting Western industrial standards of clock time (GMT, time zones, ISO standards, etc.) and the commodification of time.

Colonization of time is defined as imposing those standards and expectations as norms on the developing world.

-

'Interconnectivity', Hassan suggests, 'is what gives the network time its power within culture and society.'32 It is worth quoting him at length here. Network time does not 'kill' or render 'timeless' other temporalities, clock-time or otherwise. The embedded nature of the 'multiplicity' of temporalities rbat pervade culture and society, and tbe deeply intractable relationship we have with rhe clock make this unlikely. Rather, the process is one of 'displacement'. Network time constitutes a new and powerful temporality that is beginning to displace, neutralise, sublimate and otherwise upset other temporal relationships in our work, home and leisure environments

Hassan advances Castells' work on network time and focuses on how the cultural impact/power comes from interconnectivity of the network, not Virilio's emphasis on communication speed.

In this view, culture and society have multiple temporalities that layer/modify/supercede as globalization, political/work trends, and new technologies take hold.

Network time is displacing other types of temporal representations, like clock-time.

-

This network time transforms social time into two allied but distinct forms: simultaneity and timelessness. 29 Simultaneity refers to the globally networked immediacy of communication provided by satellite television and the internee, which makes real-time exchanges possible irrespective of the distances involved. Timelessness, the more problematic concept, refers to the layering of time, the mixing of tenses, the editing of sequences, the splicing together of unrelated events. It points co the general loss of chronological order and context-dependent rhythmicity. It combines eternity with ephemeralicy, real time with contextual change. Castells designates timeless time as 'the dominant temporality of our society'

Per Castells, network time transforms social time into two forms: simultaneity and timelessness.

Simultaneity is characterized by global, networked real-time experience augmented by technology. Timelessness is characterized by a non-linear experiences and lack of contextual rhythms. Time is undifferentiated and seems eternal and ephemeral.

Castells views timelessness as the new dominant temporal culture.

-

In Castells's analysis, time is not merely compressed but processed, and it is the network rather than acceleration that constitutes the discontinuity in a context of continuing compress10n.

compressed time vs processed time

acceleration (speed) vs network time

-

In a systematic analysis Castells contrasts the clock time of modernity with the network time of the network society.

clock time vs network time

Definition of network time, per Hassan (2003): "Through the convergence of neoliberal globalization and ICT revolution a new powerful temporality has emerged through which knowledge production is refracted: network time."

-

Virilio suggests that we can read the history of modernity as a series of innovations iu ever-increasing time compression. He argues that, through the ages, the wealth and power associated with ownership of land was equally tied to the capacity to traverse it and to the speed at which this could be achieved.

Cites French political theorist and technology critic Paul Virilio.

Virilio's engagement with speed integrates 3 concepts that evoke increasing tempos over 3 successive centuries: 19th century transport, 20th century transmission, and 21st century transplantion.

The concept of transplantation, which is more biological in origin/use, is not as broadly covered here as transport and transmission.

-

From the above we can see that Virilio understands human history in terms of a race with time, of ever-increasing speeds that transcend humans' biological capacity. To theorize culture without the dromosphere, that is, the sphere of beings in motion, he therefore sugges,ts, misses the key point of cultural activity and the uniqueness of the industrial way of life. Without an explicit conceptualization of the contemporary dromosphere -or in my terms timescape -it is thus difficult to fully understand the human-technology-science-economyequity-environmenr constellation. Moreover, it becomes impossible to appreciate that people are che weakest link when the time frames of action are compressed to zero and effects expand to eternity, when transmission and transplantation are instantaneous but their outcomes extend into an open future, when instantaneity and eternity are combined in a discordant fusion of all times.

Adam's critique of Virilio's incomplete theory on time compression as it related to cultural transformation. Claims it lacks adequate theoretical description/understanding of how people in the high-tempo dromosphere in his writings, (timescape in her work) interact with time.

Adam further notes how important it is to understand how people factor into discordant time compressions through everyday sociocultural interactions -- which she refers to as "the human-technology-science-economy-equity-environment constellation."

This is pretty dense theoretical work. Would help to find an example or two in the SBTF time study to make this idea a little more accessible.

-

the potential capacity of exterrirorial beings to be everywhere at once and nowhere in particular is inescapably tied to operators that are bounded by their embodied temporal limits of terrestrial existence and sequential information processing. The actual capacity for parallel absorption of knowledge, therefore, is hugely disappointing. Equally, the electronic capacity to be now-here and no-where has brought the body to a standstill.

Adam's critique of transmission technologies allowing people to be "now-here and no-where" perhaps also helps unpacks some of the tensions for SBTF's global social coordination.

Could this be some of the unconscious motive to use terms that situate volunteers with one another as they attempt to grapple with tempo-imposed friction points which work against "terrestrial existence" and "sequential information processing"?

-

The overload of information, for example, is becoming so extensive that taking advantage of only the tiniest fraction of it not only blows apart the principle of instantaneity and 'real-time' communication, but also slows down operators to a pomt where they lose themselves in the eternity of electronically networked information.

High tempo Information overload exacerbates time compression and thus impacts temporal sensemaking through typical means via chronologies, linear information processing, and past/present/future contexts.

-

The intensive {electronic) present, Virilio suggests, is no longer part of chronological time; we have to conceptualize it instead _as chronoscopic time. Real space, he argues, is making room for decontextualized 'real-time' processes and intensity takes over from extensity.11 This in turn has consequences and, similar to the time compression in transport, the compression in transmission has led to a range of paradoxical effects.

Definition of chronoscopic time: While still bounded and defined by clock-time, like chronological time, chronoscopic experiences are more tempo-driven and focused on a hyper-present real-time. Chronological time is situated in movement across a timeline of past, present, future where history and temporal story narrative arcs.

See Purser (2000) for a dromological analysis of Virilio's work on chronoscopic- and real-time.

-

With respect to twentieth-century transmission Virilio has in mind the wireless telegraph, telephone, radio and subsequent developments in computer and satellite communication, which have once more changed the relationship between time and movement across space. Together, these innovations in transmission replaced succession and duration with seeming simultaneity and instantaneity. Duration has been compressed to zero and the present extended spatially to encircle the globe: it became a global present.

In the example of ICT advancements (radio, telegraph, computer, etc.), Adam describes a shift in tempo of a person's temporal experience due to real-time transmission capabilities.

Tempo experiences that are successive or have some duration quality are transformed into a perceived sense of instantaneous and simultaneous "real time" experience.

When a sociotemporal experience is lighting up friction points between time and space -- is this where tempo and timelines begin to get entangled?

Is the computer-mediated "movement" between time and space the inflection point where social coordination begins to break down? That we don't have enough time to process or make sense of CMC-delivered information?

-

In economic production, time compression has been achieved by a number of means: by increasing the activity within the same unit of tifYle (through machines and the intensification of labour), reorganizing the sequence and ordering of activities (Tay!orism and Fordism), using peaks and troughs more effective!�· (flexibilization), and by eliminating all unproductive times from the process ( the just-in-time system of production, delivery and consumption).

Time compression considers how time moves across space.

Valorizing speed (aka "time compression" per Marx and CUNY Anthropology and Geography professor David Harvey) is a political and economic goal of Western industrialized nations.

Speed also provides competitive advantages, whether for technological advancements, cultural movements and species biological evolution.

-

A third paradox is only hinted at by Vmho, when he suggests that conflict is to be expected between democracy and dromocracy, the politics that take account of time and the speed of movement across space.20 It concerns the sociopolitical and socioeconomic relations associated with advances in transport speed, which affect different indivi�uals, groups and classes of society in uneven ways.

Transportation speed is entangled with social equity and power: time-poor, cash-rich can "buy" time through labor, efficient technologies but the time-rich, cash-poor cannot trade time to become wealthy wealth.

-

Rifkin and Howard point out, 'the faster we speed up, the faster we degrade

Virilio writes that speed, or time compression, also contributes to adverse social and environmental impacts, per Rifkin and Howard: "the faster we speed up, the faster we degrade."

-

In the light of this evidence, which is fully supported by transport research, 17 Virilio formulated the �romological law, which states that increase in speed mcreases the potential for gridlock.

Virilio's dromological law: "increase in speed, increases the potential for gridlock."

This evokes environmental concerns as well as critiques of political privilege/power wrt to elites with access to fast transport options and those with less clout relegated to public transportation, traffic jams, less reliable options, etc.

-

the relations of time and their socio-environmental impacts, underlying assumptions and their material expressions, institutional processes and recipients' experiences, hidden agendas and power relations, unquestioned time politics and 'othering' practices.9

Adams argues here and through her other papers(*) that social science researchers need to focus less on the obvious temporal conflicts in everyday life and focus more on the "socio-environmental impacts, underlying assumptions and their material exppressions, institutional processes and recipients' experiences, hidden agendas and power relations, unquestioned time politics and 'othering practices."

- Adam, Timescapes of Modernity and 'The Gendered Time Politics of Globalisation'.

-

While interest and credit had been known and documented since 3000 BC in Babylonia, it was not until the late Middle Ages that the Christian Church slowly and almost surreptitiously changed its position on usury,6 which set time free for trade to be allocated, sold and controlled. It is against this back�round that we have to read the extr�cts from Benjar1_1in Franklin's text of 1736, quoted at length m chapter 2, which contains the famous phrases 'Remember, that time is money ... Remember that money begets money.'7 Clock time, the created time to human design, was a precondition for this change in value and practice and formed the perfect partner to abstract, decontextualized money. From the Middle Ages, trade fairs existed where the trade in time became commonplace and calculations about future prices an integral part of commerce. In addition, internatio�al trade by sea required complex calculations about pote�ual profit and loss over long periods, given that trade ships might be away for as long as three years at a time. The time economy of interest and credit, moreover, fed directly into the monetary value of labour time, that is, paid employme�t as an integral part of the production of goo?s and serv_1ce�. However it was not until the French Revolunon that the md1-vidual (�eaning male) ownership of time became enshrined as a legal right

Historical, religious, economic, and political aspects of how time became a commodity that could be allocated, sold, traded, borrowed against or controlled.

Benjamin Franklin metaphor: "time is money ... money begets money"

-

The task for social theory, therefore, is to render the invisible visible, show relations and interconnections, begin tbe process of questioning the unquestioned. Before we can identify some of these economic relations of temporal inequity, however, we first need to understand in what way the sin of usury was a barrier to the development of economic life as we know it today in industrial societies.

Citing Weber (integrated with Marx), Adam describes how time is used to promote social inequity.

Taken for granted in a socio-economic system, time renders power relationships as invisible

-

Marx's principal point regarding the commodification of time was that an empty, abstract, quantifiable time that was applicable anywhere, any time was a precondition for its use as an abstract exchange value on the one hand and for the commodification of labour and nature on the other. Only on the basis of this neutral measure could time take such a pivotal position in all economic exchange.

Citing Marx' critique on how time is commodified for value, labor and natural resources.

-

Clock time, the human creation, as I have shown, operates according to fundamentally different principles from rhe ones ��derpinning the times of tbe cosmos, �ature and the spmt�al realm of eternity. It is a decontextuahzed empty ume that nes the measurement of motion to expression by number. Not change, creativity and process, but static states are given a number value in the temporal frames of calendars and clocks. The artifice rather than the processes of cosmos, nature and spirit, we need to appreciate, came to be the object of trade, control and colonization.

Primer on how clock-time differs from natural world and spiritual expressions of time.

Clock-time as a socio-economic numerical representation is a guiding force for how power is wielded through colonialization/conquered lands and people, labor becomes a value-laden commodity, and

-

The creation of time to human design m an atemporal, decontextualized form, as outlined in chapter 5, was a necessary techno-material condition for the use of time by industrial societies as an abstract exchange value and for the acceleration, control and global imposition of time.

Time as a techno-material condition. Tie this back to Miller (2015) on materiality?

-

This is so because all cultures, ancient and modern, have established collective ways of relating to the past and future, of synchronizing their activities, of coming to terms with finitude. How we extend ourselves into the past and future, how we pursue immortality and how we temporally manage, organize and regulate our social affairs, however, has been culturally, historically and contextually distinct. Each htstorical epoch with its new forms of socioeconomic expression is simultaneously restructuring its social relations of time.

Sociotemporal reactions/responses/concepts have deep historical roots and intercultural relationships.

Current ways of thinking about time continue to be significantly influenced by post-industrial socio-economic constructs, like clock-time, labor efficiencies (speed), and value metaphors (money, attention, thrift).

-

the Reformation had a major role to play in the metamorphosis of time from God's gift to commodified, comp�essed, colonized and controlled resource. These four Cs of mdustrial time -comrnodification, compression, colonization and control -will be the focus in these pages, the fifth C of the creation of clock time having been discussed already in the previous chapter. I show their interdependence and id�ntify some of the socio-environmental impacts of those parttcular temporal relations.

Five C's of industrial time: Commodification, compression, colonialization, control, and clock time.

-

The Quest for Time Control

Additional notes here that contrast Reddy and Adam for SBTF time study paper:

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1RNqPYmLkVV7ui06YDOSEOmod2XCXe6W3tQe9Oey2ico/edit

Tags

- materiality

- timescape

- timelessness

- history

- simultaneity

- commodification

- spatial

- labor

- sensemaking

- dromological law

- environment

- sociotemporality

- culture

- colonialization

- real time

- metaphor

- clock-time

- chronoscopic time

- compression

- information overload

- transmission

- network time

- social inequity

- interconnectivity

- Marx

- power

- speed

- colonization

- post-industrial

- control

- tempo

Annotators

URL

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

er. Each of these choices reflect power dynamics and conflicting tensions. Desires for ‘presence’ or singular focus often conflict with obligations to be responsive and integrate ‘work’ and ‘life

Are these power dynamics/tensions: actor or agent-based? individual or technical? situational or contextual? deliberate or autonomous?

-

How do we understand such mosaictime in terms of striving for balance? Temporal units are rarely single-purpose and their boundaries and dependencies are often implicit. What sociotemporal values should we be honoring? How can we account for time that fits on neither side of a scale? How might scholarship rethink balance or efficiency with different forms of accounting, with attention to institutions as well as individuals?

Design implication: What heuristics are involved in the lived experience and conflicts between temporal logic and porous time?

-

Leshed and Sengers’s research reminds us that calendars are not just tools for the management of time, but are also sites of identity work where people can project to themselves and others the density of their days and apparent ‘success’ at doing it all[26]. These seemingly innocuous artifacts can thus perpetuate deeper normative logics a

The dark side of time artifacts and the social pressure of busyness/industriousness as a virtue.

-

. When creating tools for schedulingandcoordination, it is crucial to provide ways for people to take into account not just the multiplicity of (potentially dissonant) rhythms [22, 46], but also the differential affective experiencesof time rendered by such rhythms.

Design implication: How to accommodate rhythms and obligation with social coordination work?

".. one 'chunk' of time is not equivalent to any other 'chunk'"

-

rid. The apparent equivalency of thesetime chunksmask the affective experiences and emotional intensities of lived temporality

Lived experience spotlights the tension/stress between managing chunkable time vs accepting spectral time.

How to accommodate unequal units of time? Or units that have different contextual meanings?

-