Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

eLife assessment

This important study provides solid evidence that both psychiatric dimensions (e.g. anhedonia, apathy, or depression) and chronotype (i.e., being a morning or evening person) influence effort-based decision-making. Notably, the current study does not elucidate whether there may be interactive effects of chronotype and psychiatric dimensions on decision-making. This work is of importance to researchers and clinicians alike, who may make inferences about behaviour and cognition without taking into account whether the individual may be tested or observed out-of-sync with their phenotype.

We thank the three reviewers for their comments, and the Editors at eLife. We have taken the opportunity to revise our manuscript considerably from its original form, not least because we feel a number of the reviewers’ suggested analyses strengthen our manuscript considerably (in one instance even clarifying our conclusions, leading us to change our title)—for which we are very appreciative indeed.

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Summary:

This study uses an online cognitive task to assess how reward and effort are integrated in a motivated decision-making task. In particular the authors were looking to explore how neuropsychiatric symptoms, in particular apathy and anhedonia, and circadian rhythms affect behavior in this task. Amongst many results, they found that choice bias (the degree to which integrated reward and effort affects decisions) is reduced in individuals with greater neuropsychiatric symptoms, and late chronotypes (being an 'evening person').

Strengths:

The authors recruited participants to perform the cognitive task both in and out of sync with their chronotypes, allowing for the important insight that individuals with late chronotypes show a more reduced choice bias when tested in the morning.<br />

Overall, this is a well-designed and controlled online experimental study. The modelling approach is robust, with care being taken to both perform and explain to the readers the various tests used to ensure the models allow the authors to sufficiently test their hypotheses.

Weaknesses:

This study was not designed to test the interactions of neuropsychiatric symptoms and chronotypes on decision making, and thus can only make preliminary suggestions regarding how symptoms, chronotypes and time-of-assessment interact.

We appreciate the Reviewer’s positive view of our research and agree with their assessment of its weaknesses; the study was not designed to assess chronotype-mental health interactions. We hope that our new title and contextualisation makes this clearer. We respond in more detail point-by-point below.

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Summary:

The study combines computational modeling of choice behavior with an economic, effort-based decision-making task to assess how willingness to exert physical effort for a reward varies as a function of individual differences in apathy and anhedonia, or depression, as well as chronotype. They find an overall reduction in effort selection that scales with apathy and anhedonia and depression. They also find that later chronotypes are less likely to choose effort than earlier chronotypes and, interestingly, an interaction whereby later chronotypes are especially unwilling to exert effort in the morning versus the evening.

Strengths:

This study uses state-of-the-art tools for model fitting and validation and regression methods which rule out multicollinearity among symptom measures and Bayesian methods which estimate effects and uncertainty about those estimates. The replication of results across two different kinds of samples is another strength. Finally, the study provides new information about the effects not only of chronotype but also chronotype by timepoint interactions which are previously unknown in the subfield of effort-based decision-making.

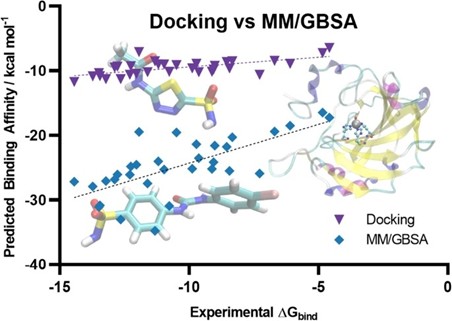

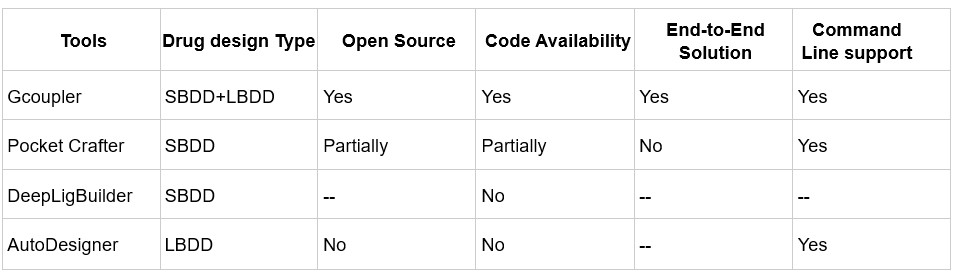

Weaknesses:

The study has few weaknesses. One potential concern is that the range of models which were tested was narrow, and other models might have been considered. For example, the Authors might have also tried to fit models with an overall inverse temperature parameter to capture decision noise. One reason for doing so is that some variance in the bias parameter might be attributed to noise, which was not modeled here. Another concern is that the manuscripts discuss effort-based choice as a transdiagnostic feature - and there is evidence in other studies that effort deficits are a transdiagnostic feature of multiple disorders. However, because the present study does not investigate multiple diagnostic categories, it doesn't provide evidence for transdiagnosticity, per se.

We appreciate Reviewer 2’s assessment of our research and agree generally with its weaknesses. We have now addressed the Reviewer’s comments regarding transdiagnosticity in the discussion of our revised version and have addressed their detailed recommendations below (see point-by-point responses).

In addition to the below specific changes, in our Discussion section, we now have also added the following (lines 538 – 540):

“Finally, we would like to note that as our study is based on a general population sample, rather than a clinical one. Hence, we cannot speak to transdiagnosticity on the level of multiple diagnostic categories.”

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

Summary:

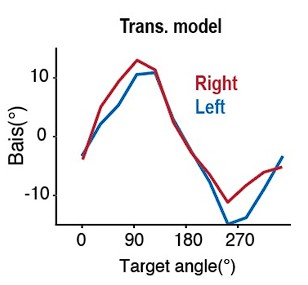

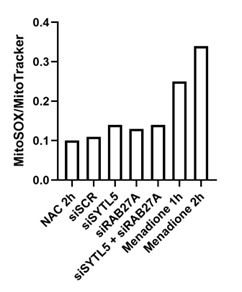

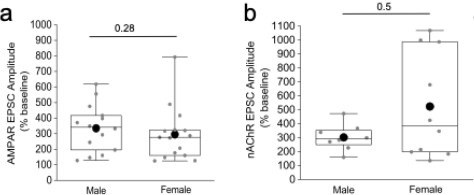

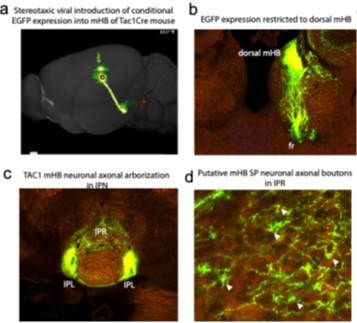

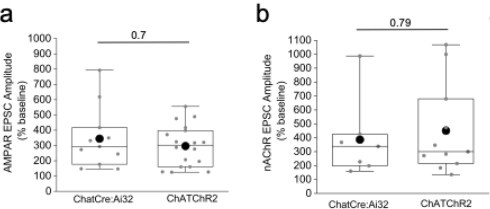

In this manuscript, Mehrhof and Nord study a large dataset of participants collected online (n=958 after exclusions) who performed a simple effort-based choice task. They report that the level of effort and reward influence choices in a way that is expected from prior work. They then relate choice preferences to neuropsychiatric syndromes and, in a smaller sample (n<200), to people's circadian preferences, i.e., whether they are a morning-preferring or evening-preferring chronotype. They find relationships between the choice bias (a model parameter capturing the likelihood to accept effort-reward challenges, like an intercept) and anhedonia and apathy, as well as chronotype. People with higher anhedonia and apathy and an evening chronotype are less likely to accept challenges (more negative choice bias). People with an evening chronotype are also more reward sensitive and more likely to accept challenges in the evening, compared to the morning.

Strengths:

This is an interesting and well-written manuscript which replicates some known results and introduces a new consideration related to potential chronotype relationships which have not been explored before. It uses a large sample size and includes analyses related to transdiagnostic as well as diagnostic criteria. I have some suggestions for improvements.

Weaknesses:

(1) The novel findings in this manuscript are those pertaining to transdiagnostic and circadian phenotypes. The authors report two separate but "overlapping" effects: individuals high on anhedonia/apathy are less willing to accept offers in the task, and similarly, individuals tested off their chronotype are less willing to accept offers in the task. The authors claim that the latter has implications for studying the former. In other words, because individuals high on anhedonia/apathy predominantly have a late chronotype (but might be tested early in the day), they might accept less offers, which could spuriously look like a link between anhedonia/apathy and choices but might in fact be an effect of the interaction between chronotype and time-of-testing. The authors therefore argue that chronotype needs to be accounted for when studying links between depression and effort tasks.

The authors argue that, if X is associated with Y and Z is associated with Y, X and Z might confound each other. That is possible, but not necessarily true. It would need to be tested explicitly by having X (anhedonia/apathy) and Z (chronotype) in the same regression model. Does the effect of anhedonia/apathy on choices disappear when accounting for chronotype (and time-of-testing)? Similarly, when adding the interaction between anhedonia/apathy, chronotype, and time-of-testing, within the subsample of people tested off their chronotype, is there a residual effect of anhedonia/apathy on choices or not?

If the effect of anhedonia/apathy disappeared (or got weaker) while accounting for chronotype, this result would suggest that chronotype mediates the effect of anhedonia/apathy on effort choices. However, I am not sure it renders the direct effect of anhedonia/apathy on choices entirely spurious. Late chronotype might be a feature (induced by other symptoms) of depression (such as fatigue and insomnia), and the association between anhedonia/apathy and effort choices might be a true and meaningful one. For example, if the effect of anhedonia/apathy on effort choices was mediated by altered connectivity of the dorsal ACC, we would not say that ACC connectivity renders the link between depression and effort choices "spurious", but we would speak of a mechanism that explains this effect. The authors should discuss in a more nuanced way what a significant mediation by the chronotype/time-of-testing congruency means for interpreting effects of depression in computational psychiatry.

We thank the Reviewer for pointing out this crucial weakness in the original version of our manuscript. We have now thought deeply about this and agree with the Reviewer that our original results did not warrant our interpretation that reported effects of anhedonia and apathy on measures of effort-based decision-making could potentially be spurious. At the Reviewer’s suggestion, we decided to test this explicitly in our revised version—a decision that has now deepened our understanding of our results, and changed our interpretation thereof.

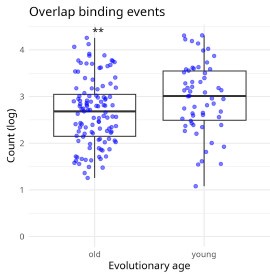

To investigate how the effects of neuropsychiatric symptoms and the effects of circadian measures relate to each other, we have followed the Reviewer’s advice and conducted an additional series of analyses (see below). Surprisingly (to us, but perhaps not the Reviewer) we discovered that all three symptom measures (two of anhedonia, one of apathy) have separable effects from circadian measures on the decision to expend effort (note we have also re-named our key parameter ‘motivational tendency’ to address this Reviewer’s next comment that the term ‘choice bias’ was unclear). In model comparisons (based on leave-one-out information criterion which penalises for model complexity) the models including both circadian and psychiatric measures always win against the models including either circadian or psychiatric measures. In essence, this strengthens our claims about the importance of measuring circadian rhythm in effort-based tasks generally, as circadian rhythm clearly plays an important role even when considering neuropsychiatric symptoms, but crucially does not support the idea of spurious effects: statistically, circadian measures contributes separably from neuropsychiatric symptoms to the variance in effort-based decision-making. We think this is very interesting indeed, and certainly clarifies (and corrects the inaccuracy in) our original interpretation—and can only express our thanks to the Reviewer for helping us understand our effect more fully.

In response to these new insights, we have made numerous edits to our manuscript. First, we changed the title from “Overlapping effects of neuropsychiatric symptoms and circadian rhythm on effort-based decision-making” to “Both neuropsychiatric symptoms and circadian rhythm alter effort-based decision-making”. In the remaining manuscript we now refrain from using the word ‘overlapping’ (which could be interpreted as overlapping in explained variance), and instead opted to describe the effects as parallel. We hope our new analyses, title, and clarified/improved interpretations together address the Reviewer’s valid concern about our manuscript’s main weakness.

We detail these new analyses in the Methods section as follows (lines 800 – 814):

“4.5.2. Differentiating between the effects of neuropsychiatric symptoms and circadian measures on motivational tendency

To investigate how the effects of neuropsychiatric symptoms on motivational tendency (2.3.1) relate to effects of chronotype and time-of-day on motivational tendency we conducted exploratory analyses. In the subsamples of participants with an early or late chronotype (including additionally collected data), we first ran Bayesian GLMs with neuropsychiatric questionnaire scores (SHAPS, DARS, AES respectively) predicting motivational tendency, controlling for age and gender. We next added an interaction term of chronotype and time-of-day into the GLMs, testing how this changes previously observed neuropsychiatric and circadian effects on motivational tendency. Finally, we conducted a model comparison using LOO, comparing between motivational tendency predicted by a neuropsychiatric questionnaire, motivational tendency predicted by chronotype and time-of-day, and motivational tendency predicted by a neuropsychiatric questionnaire and time-of-day (for each neuropsychiatric questionnaire, and controlling for age and gender).”

Results of the outlined analyses are reported in the results section as follows (lines 356 – 383):

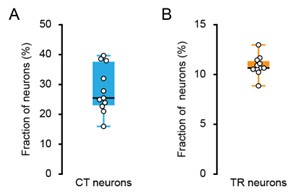

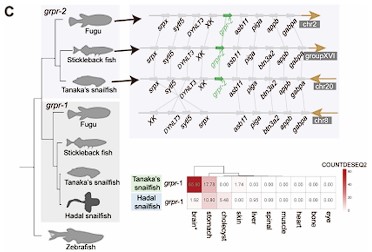

“2.5.2.1 Neuropsychiatric symptoms and circadian measures have separable effects on motivational tendency

Exploratory analyses testing for the effects of neuropsychiatric questionnaires on motivational tendency in the subsamples of early and late chronotypes confirmed the predictive value of the SHAPS (M=-0.24, 95% HDI=[-0.42,-0.06]), the DARS (M=-0.16, 95% HDI=[-0.31,-0.01]), and the AES (M=-0.18, 95% HDI=[-0.32,-0.02]) on motivational tendency.

For the SHAPS, we find that when adding the measures of chronotype and time-of-day back into the GLMs, the main effect of the SHAPS (M=-0.26, 95% HDI=[-0.43,-0.07]), the main effect of chronotype (M=-0.11, 95% HDI=[-0.22,-0.01]), and the interaction effect of chronotype and time-of-day (M=0.20, 95% HDI=[0.07,0.34]) on motivational tendency remain. Model comparison by LOOIC reveals motivational tendency is best predicted by the model including the SHAPS, chronotype and time-of-day as predictors, followed by the model including only the SHAPS. Note that this approach to model comparison penalizes models for increasing complexity.

Repeating these steps with the DARS, the main effect of the DARS is found numerically, but the 95% HDI just includes 0 (M=-0.15, 95% HDI=[-0.30,0.002]). The main effect of chronotype (M=-0.11, 95% HDI=[-0.21,-0.01]), and the interaction effect of chronotype and time-of-day (M=0.18, 95% HDI=[0.05,0.33]) on motivational tendency remain. Model comparison identifies the model including the DARS and circadian measures as the best model, followed by the model including only the DARS.

For the AES, the main effect of the AES is found (M=-0.19, 95% HDI=[-0.35,-0.04]). For the main effect of chronotype, the 95% narrowly includes 0 (M=-0.10, 95% HDI=[-0.21,0.002]), while the interaction effect of chronotype and time-of-day (M=0.20, 95% HDI=[0.07,0.34]) on motivational tendency remains. Model comparison identifies the model including the AES and circadian measures as the best model, followed by the model including only the AES.”

We have now edited parts of our Discussion to discuss and reflect these new insights, including the following.

Lines 399 – 402:

“Various neuropsychiatric disorders are marked by disruptions in circadian rhythm, such as a late chronotype. However, research has rarely investigated how transdiagnostic mechanisms underlying neuropsychiatric conditions may relate to inter-individual differences in circadian rhythm.”

Lines 475 – 480:

“It is striking that the effects of neuropsychiatric symptoms on effort-based decision-making largely are paralleled by circadian effects on the same neurocomputational parameter. Exploratory analyses predicting motivational tendency by neuropsychiatric symptoms and circadian measures simultaneously indicate the effects go beyond recapitulating each other, but rather explain separable parts of the variance in motivational tendency.”

Lines 528 – 532:

“Our reported analyses investigating neuropsychiatric and circadian effects on effort-based decision-making simultaneously are exploratory, as our study design was not ideally set out to examine this. Further work is needed to disentangle separable effects of neuropsychiatric and circadian measures on effort-based decision-making.”

Lines 543 – 550:

“We demonstrate that neuropsychiatric effects on effort-based decision-making are paralleled by effects of circadian rhythm and time-of-day. Exploratory analyses suggest these effects account for separable parts of the variance in effort-based decision-making. It unlikely that effects of neuropsychiatric effects on effort-based decision-making reported here and in previous literature are a spurious result due to multicollinearity with chronotype. Yet, not accounting for chronotype and time of testing, which is the predominant practice in the field, could affect results.”

(2) It seems that all key results relate to the choice bias in the model (as opposed to reward or effort sensitivity). It would therefore be helpful to understand what fundamental process the choice bias is really capturing in this task. This is not discussed, and the direction of effects is not discussed either, but potentially quite important. It seems that the choice bias captures how many effortful reward challenges are accepted overall which maybe captures general motivation or task engagement. Maybe it is then quite expected that this could be linked with questionnaires measuring general motivation/pleasure/task engagement. Formally, the choice bias is the constant term or intercept in the model for p(accept), but the authors never comment on what its sign means. If I'm not mistaken, people with higher anhedonia but also higher apathy are less likely to accept challenges and thus engage in the task (more negative choice bias). I could not find any discussion or even mention of what these results mean. This similarly pertains to the results on chronotype. In general, "choice bias" may not be the most intuitive term and the authors may want to consider renaming it. Also, given the sign of what the choice bias means could be flipped with a simple sign flip in the model equation (i.e., equating to accepting more vs accepting less offers), it would be helpful to show some basic plots to illustrate the identified differences (e.g., plotting the % accepted for people in the upper and lower tertile for the SHAPS score etc).

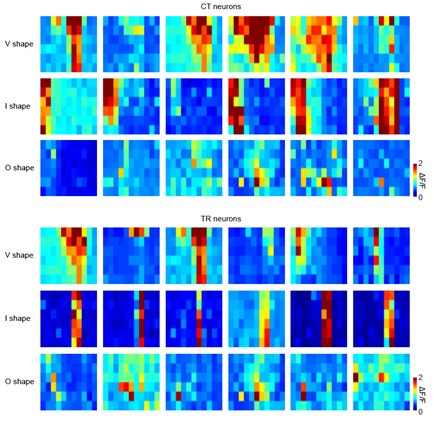

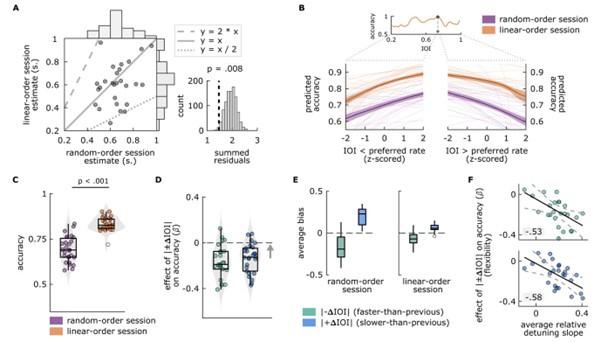

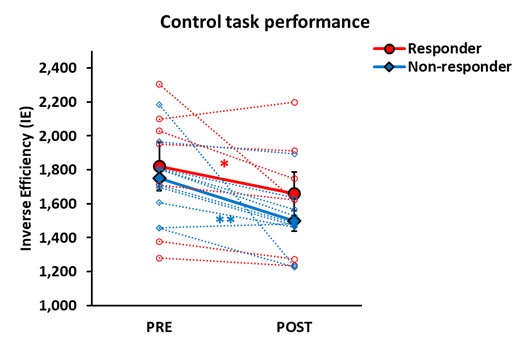

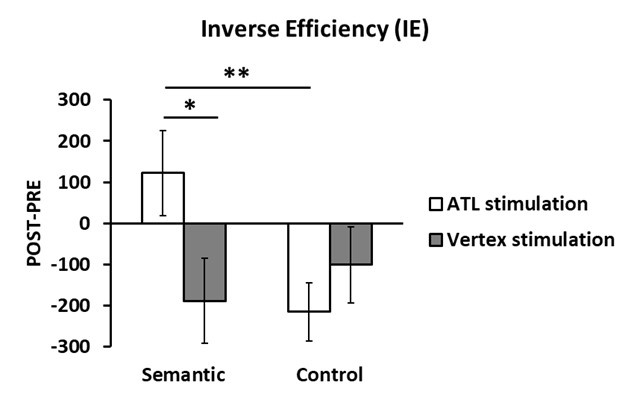

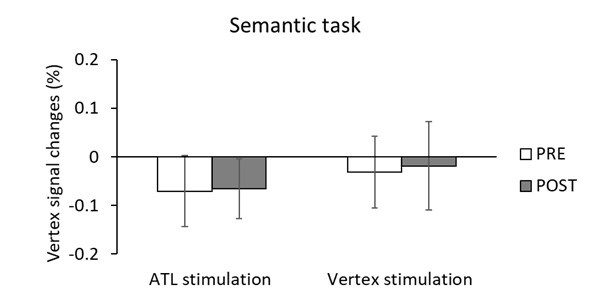

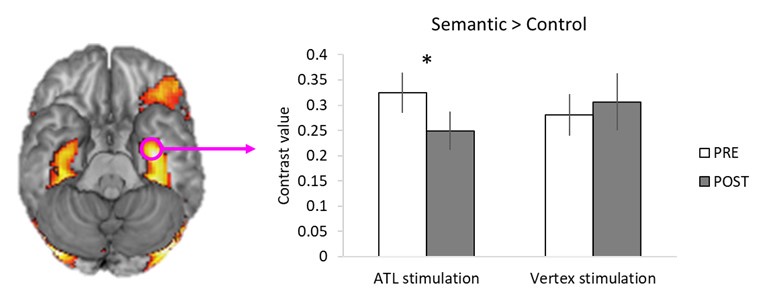

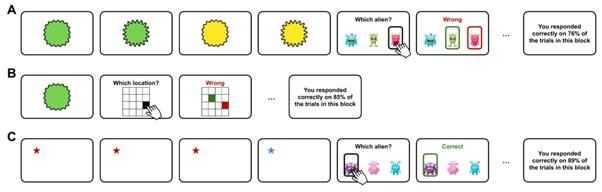

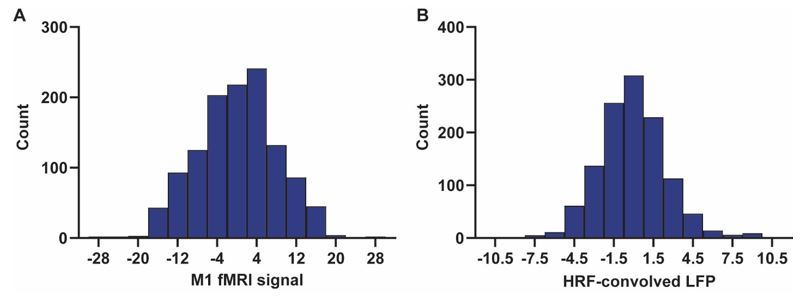

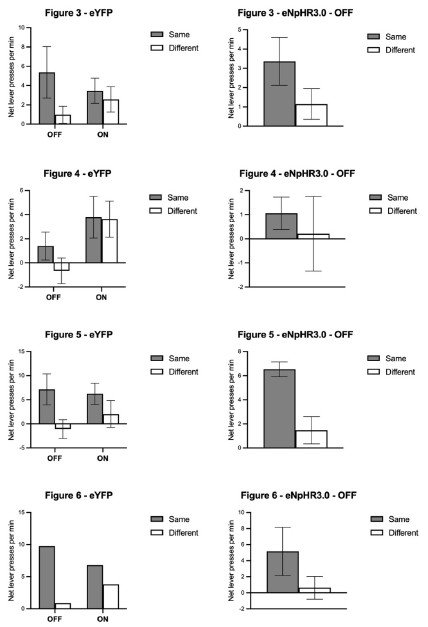

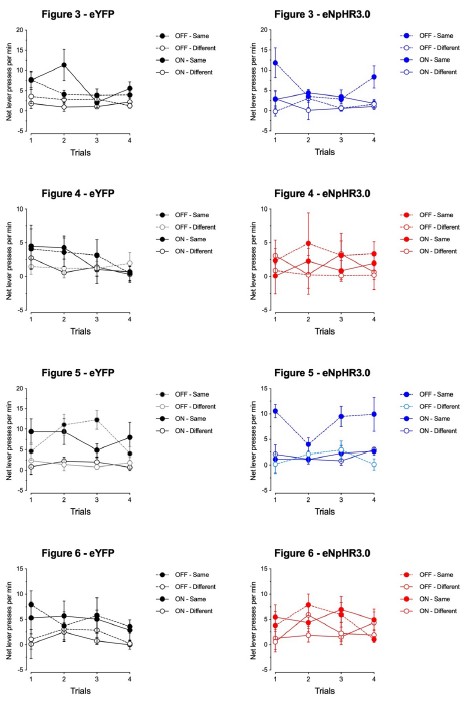

We apologise that this was not made clear previously: the meaning and directionality of “choice bias” is indeed central to our results. We also thank the Reviewer for pointing out the previousely-used term “choice bias” itself might not be intuitive. We have now changed this to ‘motivational tendency’ (see below) as well as added substantial details on this parameter to the manuscript, including additional explanations and visualisations of the model as suggested by the Reviewer (new Figure 3) and model-agnostic results to aid interpretation (new Figure S3). Note the latter is complex due to our staircasing procedure (see new figure panel D further detailing our staircasing procedure in Figure 2). This shows that participants with more pronounced anhedonia are less likely to accept offers than those with low anhedonia (Fig. S3A), a model-agnostic version of our central result.

Our changes are detailed below:

After careful evaluation we have decided to term the parameter “motivational tendency”, hoping that this will present a more intuitive description of the parameter.

To aid with the understanding and interpretation of the model parameters, and motivational tendency in particular, we have added the following explanation to the main text:

Lines 149 – 155:

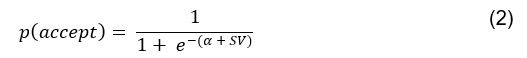

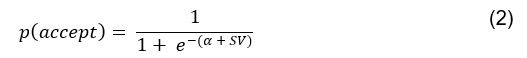

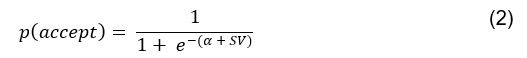

“The models posit efforts and rewards are joined into a subjective value (SV), weighed by individual effort (and reward sensitivity (parameters. The subjective value is then integrated with an individual motivational tendency (a) parameter to guide decision-making. Specifically, the motivational tendency parameter determines the range at which subjective values are translated to acceptance probabilities: the same subjective value will translate to a higher acceptance probability the higher the motivational tendency.”

Further, we have included a new figure, visualizing the model. This demonstrates how the different model parameters contribute to the model (A), and how different values on each parameter affects the model (B-D).

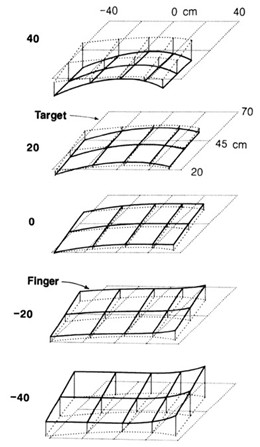

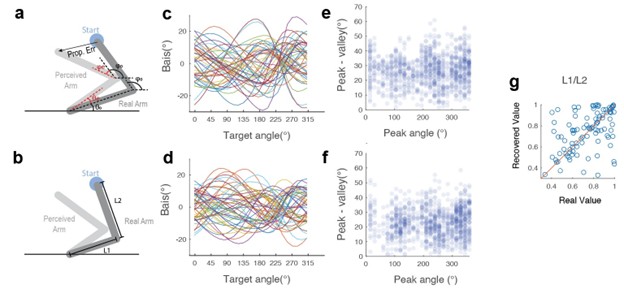

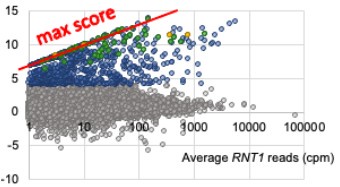

We agree that plotting model agnostic effects in our data may help the reader gain intuition of what our task results mean. We hope to address this with our added section on “Model agnostic task measures relating to questionnaires”. We first followed the reviewer’s suggestion of extracting subsamples with higher and low anhedonia (as measured with the SHAPS, highest and lowest quantile) and plotted the acceptance proportion across effort and reward levels (panel A in figure below). However, due to our implemented task design, this only shows part of the picture: the staircasing procedure individualises which effort-reward combination a participant is presented with. Therefore, group differences in choice behaviour will lead to differences in the development of the staircases implemented in our task. Thus, we plotted the count of offered effort-reward combinations for the subsamples of participants with high vs. low SHAPS scores by the end of the task, averaged across staircases and participants.

As the aspect of task development due to the implemented staircasing may not have been explained sufficiently in the main text, we have included panel (D) in figure 2.

Further, we have added the following figure reference to the main text (lines 189 – 193):

“The development of offered effort and reward levels across trials is shown in figure 2D; this shows that as participants generally tend to accept challenges rather than reject them, the implemented staircasing procedure develops toward higher effort and lover reward challenges.”

To statistically test effects of model-agnostic task measures on the neuropsychiatric questionnaires, we performed Bayesian GLMs with the proportion of accepted trials predicted by SHAPS and AES. This is reported in the text as follows.

Supplement, lines 172 – 189:

“To explore the relationship between model agnostic task measures to questionnaire measures of neuropsychiatric symptoms, we conducted Bayesian GLMs, with the proportion of accepted trials predicted by SHAPS scores, controlling for age and gender. The proportion of accepted trials averaged across effort and reward levels was predicted by the Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale (SHAPS) sum scores (M=-0.07; 95%HDI=[-0.12,-0.03]) and the Apathy Evaluation Scale (AES) sum scores (M=-0.05; 95%HDI=[-0.10,-0.002]). Note that this was not driven only by higher effort levels; even confining data to the lowest two effort levels, SHAPS has a predictive value for the proportion of accepted trials: M=-0.05; 95%HDI=[-0.07,-0.02].<br />

A visualisation of model agnostic task measures relating to symptoms is given in Fig. S4, comparing subgroups of participants scoring in the highest and lowest quartile on the SHAPS. This shows that participants with a high SHAPS score (i.e., more pronounced anhedonia) are less likely to accept offers than those with a low SHAPS score (Fig. S4A). Due to the implemented staircasing procedure, group differences can also be seen in the effort-reward combinations offered per trial. While for both groups, the staircasing procedure seems to devolve towards high effort – low reward offers, this is more pronounced in the subgroup of participants with a lower SHAPS score (Fig S4B).”

(3) None of the key effects relate to effort or reward sensitivity which is somewhat surprising given the previous literature and also means that it is hard to know if choice bias results would be equally found in tasks without any effort component. (The only analysis related to effort sensitivity is exploratory and in a subsample of N=56 per group looking at people meeting criteria for MDD vs matched controls.) Were stimuli constructed such that effort and reward sensitivity could be separated (i.e., are uncorrelated/orthogonal)? Maybe it would be worth looking at the % accepted in the largest or two largest effort value bins in an exploratory analysis. It seems the lowest and 2nd lowest effort level generally lead to accepting the challenge pretty much all the time, so including those effort levels might not be sensitive to individual difference analyses?

We too were initially surprised by the lack of effect of neuropsychiatric symptoms on reward and effort sensitivity. To address the Reviewer’s first comment, the nature of the ‘choice bias’ parameter (now motivational tendency) is its critical importance in the context of effort-based decision-making: it is not modelled or measured explicitly in tasks without effort (such as typical reward tasks), so it would be impossible to test this in tasks without an effort component.

For the Reviewer’s second comment, the exploratory MDD analysis is not our only one related to effort sensitivity: the effort sensitivity parameter is included in all of our central analyses, and (like reward sensitivity), does not relate to our measured neuropsychiatric symptoms (e.g., see page 15). Note most previous effort tasks do not include a ‘choice bias’/motivational tendency parameter, potentially explaining this discrepancy. However, our model was quantitatively superior to models without this parameter, for example with only effort- and reward-sensitivity (page 11, Fig. 3).

Our three model parameters (reward sensitivity, effort sensitivity, and choice bias/motivational tendency) were indeed uncorrelated/orthogonal to one another (see parameter orthogonality analyses below), making it unlikely that the variance and effect captured by our motivational tendency parameter (previously termed “choice bias”) should really be attributed to reward sensitivity. As per the Reviewer’s suggestion, we also examined whether the lowest two effort levels might not be sensitive to individual differences; in fact, we found out proportion of accepted trials on the lowest effort levels alone was nevertheless predicted by anhedonia (see ceiling effect analyses below).

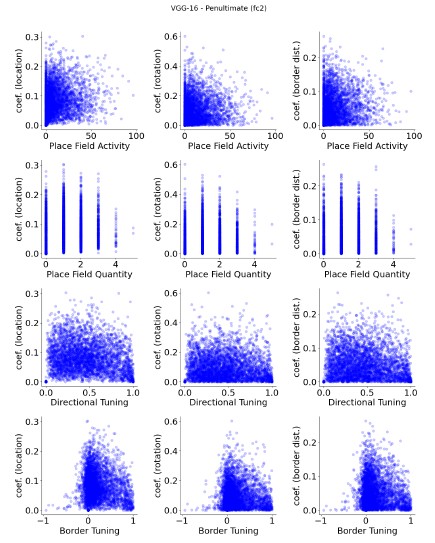

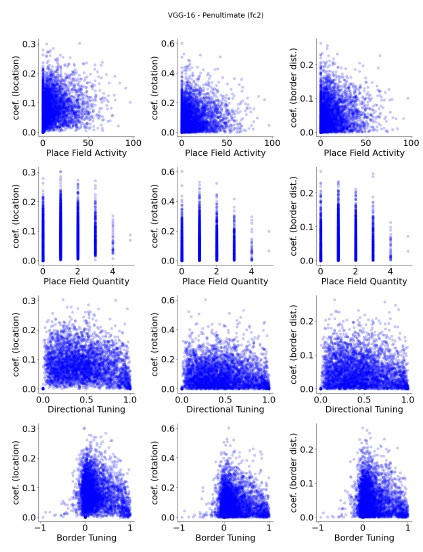

Specifically, in terms of parameter orthogonality:

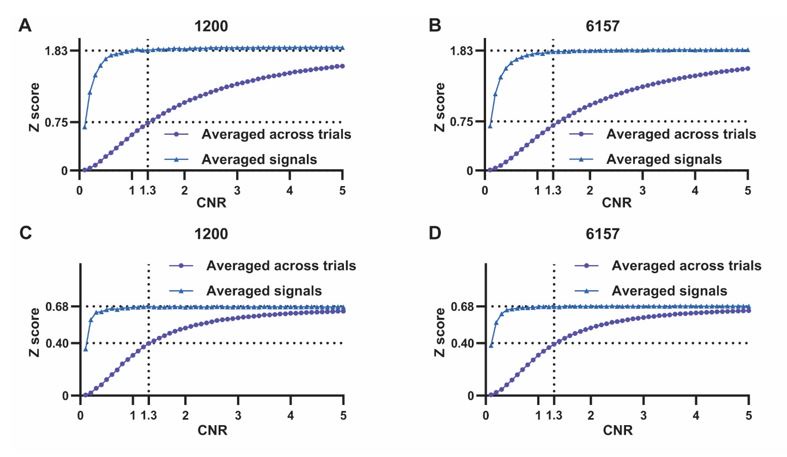

When developing our task design and computational modelling approach we were careful to ensure that meaningful neurocomputational parameters could be estimated and that no spurious correlations between parameters would be introduced by modelling. By conducting parameter recoveries for all models, we showed that our modelling approach could reliably estimate parameters, and that estimated parameters are orthogonal to the other underlying parameters (as can be seen in Figure S1 in the supplement). It is thus unlikely that the variance and effect captured by our motivational tendency parameter (previously termed “choice bias”) should really be attributed to reward sensitivity.

And finally, regarding the possibility of a ceiling effect for low effort levels:

We agree that visual inspection of the proportion of accepted results across effort and reward values can lead to the belief that a ceiling effect prevents the two lowest effort levels from capturing any inter-individual differences. To test whether this is the case, we ran a Bayesian GLM with the SHAPS sum score predicting the proportion of accepted trials (controlling for age and gender), in a subset of the data including only trials with an effort level of 1 or 2. We found the SHAPS has a predictive value for the proportion of accepted trials in the lowest two effort levels: M=-0.05; 95%HDI=[-0.07,-0.02]). This is noted in the text as follows.

Supplement, lines 175 – 180:

“The proportion of accepted trials averaged across effort and reward levels was predicted by the Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale (SHAPS) sum scores (M=-0.07; 95%HDI=[-0.12,-0.03]) and the Apathy Evaluation Scale (AES) sum scores (M=-0.05; 95%HDI=[-0.10,-0.002]). Note that this was not driven only by higher effort levels; even confining data to the lowest two effort levels, SHAPS has a predictive value for the proportion of accepted trials: M=-0.05; 95%HDI=[-0.07,-0.02].”

(4) The abstract and discussion seem overstated (implications for the school system and statements on circadian rhythms which were not measured here). They should be toned down to reflect conclusions supported by the data.

We thank the Reviewer for pointing this out, and have now removed these claims from the abstract and Discussion; we hope they now better reflect conclusions supported by these data directly.

Recommendations for the authors:

Reviewer #1 (Recommendations For The Authors):

(1) Suggestions for improved or additional experiments, data or analyses.

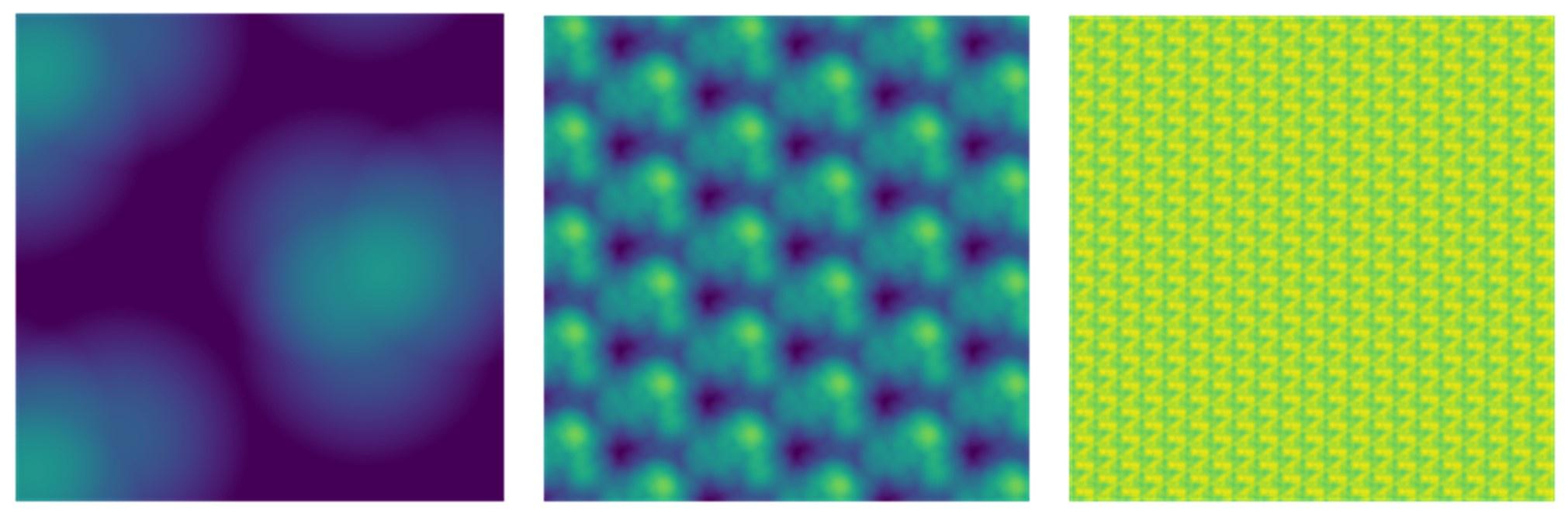

- For a non-computational audience, it would be useful to unpack the influence of the choice bias on behavior, as it is less clear how this would affect decision-making than sensitivity to effort or reward. Perhaps a figure showing accept/reject decisions when sensitivities are held and choice bias is high would be beneficial.

We thank the Reviewer for suggesting additional explanations of the choice bias parameter to aid interpretation for non-computational readers; as per the Reviewer’s suggestion, we have now included additional explanations and visualisations (Figure 3) to make this as clear as possible. Please note also that, in response to one of the other Reviewers and after careful considerations, we have decided to rename the “choice bias” parameter to “motivational tendency”, hoping this will prove more intuitive.

To aid with the understanding and interpretation of this and the other model parameters, we have added the following explanation to the main text.

Lines 149 – 155:

“The models posit efforts and rewards are joined into a subjective value (SV), weighed by individual effort (and reward sensitivity (parameters. The subjective value is then integrated with an individual motivational tendency (a) parameter to guide decision-making. Specifically, the motivational tendency parameter determines the range at which subjective values are translated to acceptance probabilities: the same subjective value will translate to a higher acceptance probability the higher the motivational tendency.”

Additionally, we add the following explanation to the Methods section.

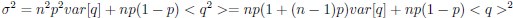

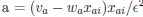

Lines 698 – 709:

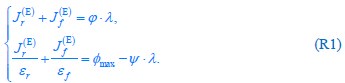

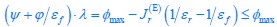

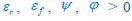

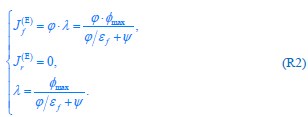

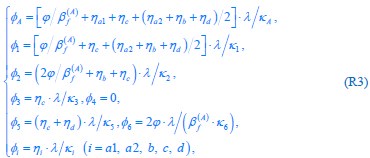

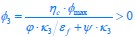

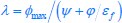

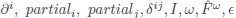

First, a cost function transforms costs and rewards associated with an action into a subjective value (SV):

with  and

and  for reward and effort sensitivity, and ℛ and 𝐸 for reward and effort. Higher effort and reward sensitivity mean the SV is more strongly influenced by changes in effort and reward, respectively (Fig. 3B-C). Hence, low effort and reward sensitivity mean the SV, and with that decision-making, is less guided by effort and reward offers, as would be in random decision-making.

for reward and effort sensitivity, and ℛ and 𝐸 for reward and effort. Higher effort and reward sensitivity mean the SV is more strongly influenced by changes in effort and reward, respectively (Fig. 3B-C). Hence, low effort and reward sensitivity mean the SV, and with that decision-making, is less guided by effort and reward offers, as would be in random decision-making.

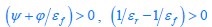

This SV is then transformed to an acceptance probability by a softmax function:

with  for the predicted acceptance probability and 𝛼 for the intercept representing motivational tendency. A high motivational tendency means a subjects has a tendency, or bias, to accept rather than reject offers (Fig. 3D).

for the predicted acceptance probability and 𝛼 for the intercept representing motivational tendency. A high motivational tendency means a subjects has a tendency, or bias, to accept rather than reject offers (Fig. 3D).

Our new figure (panels A-D in figure 3) visualizes the model. This demonstrates how the different model parameters come at play in the model (A), and how different values on each parameter affects the model (B-D).

- The early and late chronotype groups have significant differences in ages and gender. Additional supplementary analysis here may mitigate any concerns from readers.

The Reviewer is right to notice that our subsamples of early and late chronotypes differ significantly in age and gender, but it important to note that all our analyses comparing these two groups take this into account, statistically controlling for age and gender. We regret that this was previously only mentioned in the Methods section, so this information was not accessible where most relevant. To remedy this, we have amended the Results section as follows.

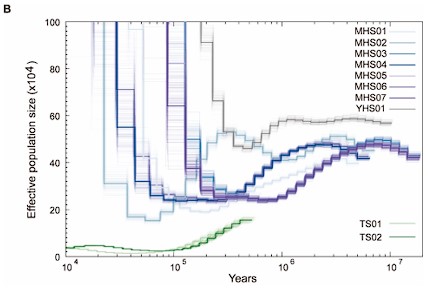

Lines 317 – 323:

“Bayesian GLMs, controlling for age and gender, predicting task parameters by time-of-day and chronotype showed effects of chronotype on reward sensitivity (i.e. those with a late chronotype had a higher reward sensitivity; M= 0.325, 95% HDI=[0.19,0.46]) and motivational tendency (higher in early chronotypes; M=-0.248, 95% HDI=[-0.37,-0.11]), as well as an interaction between chronotype and time-of-day on motivational tendency (M=0.309, 95% HDI=[0.15,0.48]).”

(2) Recommendations for improving the writing and presentation.

- I found the term 'overlapping' a little jarring. I think the authors use it to mean both neuropsychiatric symptoms and chronotypes affect task parameters, but they are are not tested to be 'separable', nor is an interaction tested. Perhaps being upfront about how interactions are not being tested here (in the introduction, and not waiting until the discussion) would give an opportunity to operationalize this term.

We agree with the Reviewer that our previously-used term “overlapping” was not ideal: it may have been misleading, and was not necessarily reflective of the nature of our findings. We now state explicitly that we are not testing an interaction between neuropsychiatric symptoms and chronotypes in our primary analyses. Additionally, following suggestions made by Reviewer 3, we ran new exploratory analyses to investigate how the effects of neuropsychiatric symptoms and circadian measures on motivational tendency relate to one another. These results in fact show that all three symptom measures have separable effects from circadian measures on motivational tendency. This supports the Reviewer’s view that ‘overlapping’ was entirely the wrong word—although it nevertheless shows the important contribution of circadian rhythm as well as neuropsychiatric symptoms in effort-based decision-making. We have changed the manuscript throughout to better describe this important, more accurate interpretation of our findings, including replacing the term “overlapping”. We changed the title from “Overlapping effects of neuropsychiatric symptoms and circadian rhythm on effort-based decision-making” to “Both neuropsychiatric symptoms and circadian rhythm alter effort-based decision-making”.

To clarify the intention of our primary analyses, we have added the following to the last paragraph of the introduction.

Lines 107 – 112:

“Next, we pre-registered a follow-up experiment to directly investigate how circadian preference interacts with time-of-day on motivational decision-making, using the same task and computational modelling approach. While this allows us to test how circadian effects on motivational decision-making compare to neuropsychiatric effects, we do not test for possible interactions between neuropsychiatric symptoms and chronobiology.”

We detail our new analyses in the Methods section as follows.

Lines 800 – 814:

“4.5.2 Differentiating between the effects of neuropsychiatric symptoms and circadian measures on motivational tendency

To investigate how the effects of neuropsychiatric symptoms on motivational tendency (2.3.1) relate to effects of chronotype and time-of-day on motivational tendency we conducted exploratory analyses. In the subsamples of participants with an early or late chronotype (including additionally collected data), we first ran Bayesian GLMs with neuropsychiatric questionnaire scores (SHAPS, DARS, AES respectively) predicting motivational tendency, controlling for age and gender. We next added an interaction term of chronotype and time-of-day into the GLMs, testing how this changes previously observed neuropsychiatric and circadian effects on motivational tendency. Finally, we conducted a model comparison using LOO, comparing between motivational tendency predicted by a neuropsychiatric questionnaire, motivational tendency predicted by chronotype and time-of-day, and motivational tendency predicted by a neuropsychiatric questionnaire and time-of-day (for each neuropsychiatric questionnaire, and controlling for age and gender).”

Results of the outlined analyses are reported in the Results section as follows.

Lines 356 – 383:

“2.5.2.1 Neuropsychiatric symptoms and circadian measures have separable effects on motivational tendency

Exploratory analyses testing for the effects of neuropsychiatric questionnaires on motivational tendency in the subsamples of early and late chronotypes confirmed the predictive value of the SHAPS (M=-0.24, 95% HDI=[-0.42,-0.06]), the DARS (M=-0.16, 95% HDI=[-0.31,-0.01]), and the AES (M=-0.18, 95% HDI=[-0.32,-0.02]) on motivational tendency.

For the SHAPS, we find that when adding the measures of chronotype and time-of-day back into the GLMs, the main effect of the SHAPS (M=-0.26, 95% HDI=[-0.43,-0.07]), the main effect of chronotype (M=-0.11, 95% HDI=[-0.22,-0.01]), and the interaction effect of chronotype and time-of-day (M=0.20, 95% HDI=[0.07,0.34]) on motivational tendency remain. Model comparison by LOOIC reveals motivational tendency is best predicted by the model including the SHAPS, chronotype and time-of-day as predictors, followed by the model including only the SHAPS. Note that this approach to model comparison penalizes models for increasing complexity.

Repeating these steps with the DARS, the main effect of the DARS is found numerically, but the 95% HDI just includes 0 (M=-0.15, 95% HDI=[-0.30,0.002]). The main effect of chronotype (M=-0.11, 95% HDI=[-0.21,-0.01]), and the interaction effect of chronotype and time-of-day (M=0.18, 95% HDI=[0.05,0.33]) on motivational tendency remain. Model comparison identifies the model including the DARS and circadian measures as the best model, followed by the model including only the DARS.

For the AES, the main effect of the AES is found (M=-0.19, 95% HDI=[-0.35,-0.04]). For the main effect of chronotype, the 95% narrowly includes 0 (M=-0.10, 95% HDI=[-0.21,0.002]), while the interaction effect of chronotype and time-of-day (M=0.20, 95% HDI=[0.07,0.34]) on motivational tendency remains. Model comparison identifies the model including the AES and circadian measures as the best model, followed by the model including only the AES.”

In addition to the title change, we edited our Discussion to discuss and reflect these new insights, including the following.

Lines 399 – 402:

“Various neuropsychiatric disorders are marked by disruptions in circadian rhythm, such as a late chronotype. However, research has rarely investigated how transdiagnostic mechanisms underlying neuropsychiatric conditions may relate to inter-individual differences in circadian rhythm.”

Lines 475 – 480:

“It is striking that the effects of neuropsychiatric symptoms on effort-based decision-making largely are paralleled by circadian effects on the same neurocomputational parameter. Exploratory analyses predicting motivational tendency by neuropsychiatric symptoms and circadian measures simultaneously indicate the effects go beyond recapitulating each other, but rather explain separable parts of the variance in motivational tendency.”

Lines 528 – 532:

“Our reported analyses investigating neuropsychiatric and circadian effects on effort-based decision-making simultaneously are exploratory, as our study design was not ideally set out to examine this. Further work is needed to disentangle separable effects of neuropsychiatric and circadian measures on effort-based decision-making.”

Lines 543 – 550:

“We demonstrate that neuropsychiatric effects on effort-based decision-making are paralleled by effects of circadian rhythm and time-of-day. Exploratory analyses suggest these effects account for separable parts of the variance in effort-based decision-making. It unlikely that effects of neuropsychiatric effects on effort-based decision-making reported here and in previous literature are a spurious result due to multicollinearity with chronotype. Yet, not accounting for chronotype and time of testing, which is the predominant practice in the field, could affect results.”

- A minor point, but it could be made clearer that many neurotransmitters have circadian rhythms (and not just dopamine).

We agree this should have been made clearer, and have added the following to the Introduction.

Lines 83 – 84:

“Bi-directional links between chronobiology and several neurotransmitter systems have been reported, including dopamine47.

(47) Kiehn, J.-T., Faltraco, F., Palm, D., Thome, J. & Oster, H. Circadian Clocks in the Regulation of Neurotransmitter Systems. Pharmacopsychiatry 56, 108–117 (2023).”

- Making reference to other studies which have explored circadian rhythms in cognitive tasks would allow interested readers to explore the broader field. One such paper is: Bedder, R. L., Vaghi, M. M., Dolan, R. J., & Rutledge, R. B. (2023). Risk taking for potential losses but not gains increases with time of day. Scientific reports, 13(1), 5534, which also includes references to other similar studies in the discussion.

We thank the Reviewer for pointing out that we failed to cite this relevant work. We have now included it in the Introduction as follows.

Lines 97 – 98:

“A circadian effect on decision-making under risk is reported, with the sensitivity to losses decreasing with time-of-day66.

(66) Bedder, R. L., Vaghi, M. M., Dolan, R. J. & Rutledge, R. B. Risk taking for potential losses but not gains increases with time of day. Sci Rep 13, 5534 (2023).”

(3) Minor corrections to the text and figures.

None, clearly written and structured. Figures are high quality and significantly aid understanding.

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations For The Authors):

I did have a few more minor comments:

- The manuscript doesn't clarify whether trials had time limits - so that participants might fail to earn points - or instead they did not and participants had to continue exerting effort until they were done. This is important to know since it impacts on decision-strategies and behavioral outcomes that might be analyzed. For example, if there is no time limit, it might be useful to examine the amount of time it took participants to complete their effort - and whether that had any relationship to choice patterns or symptomatology. Or, if they did, it might be interesting to test whether the relationship between choices and exerted effort depended on symptoms. For example, someone with depression might be less willing to choose effort, but just as, if not more likely to successfully complete a trial once it is selected.

We thank the Reviewer for pointing out this important detail in the task design, which we should have made clearer. The trials did indeed have a time limit which was dependent on the effort level. To clarify this in the manuscript, we have made changes to Figure 2 and the Methods section. We agree it would be interesting to explore whether the exerted effort in the task related to symptoms. We explored this in our data by predicting the participant average proportion of accepted but failed trials by SHAPS score (controlling for age and gender). We found no relationship: M=0.01, 95% HDI=[-0.001,0.02]. However, it should be noted that the measure of proportion of failed trials may not be suitable here, as there are only few accepted but failed trials (M = 1.3% trials failed, SD = 3.50). This results from several task design characteristics aimed at preventing subjects from failing accepted trials, to avoid confounding of effort discounting with risk discounting. As an alternative measure, we explored the extent to which participants went “above and beyond” the target in accepted trials. Specifically, considering only accepted and succeeded trials, we computed the factor by which the required number of clicks was exceeded (i.e., if a subject clicked 15 times when 10 clicks were required the factor would be 1.3), averaging across effort and reward level. We then conducted a Bayesian GLM to test whether this subject wise click-exceedance measure can be predicted by apathy or anhedonia, controlling for age and gender. We found neither the SHAPS (M=-0.14, 95% HDI=[-0.43,0.17]) nor the AES (M=0.07, 95% HDI=[-0.26,0.41]) had a predictive value for the amount to which subjects exert “extra effort”. We have now added this to the manuscript.

In Figure 2, which explains the task design in the results section, we have added the following to the figure description.

Lines 161 – 165:

“Each trial consists of an offer with a reward (2,3,4, or 5 points) and an effort level (1,2,3, or 4, scaled to the required clicking speed and time the clicking must be sustained for) that subjects accept or reject. If accepted, a challenge at the respective effort level must be fulfilled for the required time to win the points.”

In the Methods section, we have added the following.

Lines 617 – 622:

“We used four effort-levels, corresponding to a clicking speed at 30% of a participant’s maximal capacity for 8 seconds (level 1), 50% for 11 seconds (level 2), 70% for 14 seconds (level 3), and 90% for 17 seconds (level 4). Therefore, in each trial, participants had to fulfil a certain number of mouse clicks (dependent on their capacity and the effort level) in a specific time (dependent on the effort level).”

In the Supplement, we have added the additional analyses suggested by the Reviewer.

Lines 195 – 213:

“3.2 Proportion of accepted but failed trials

For each participant, we computed the proportion of trial in which an offer was accepted, but the required effort then not fulfilled (i.e., failed trials). There was no relationship between average proportion of accepted but failed trials and SHAPS score (controlling for age and gender): M=0.01, 95% HDI=[-0.001,0.02]. However, there are intentionally few accepted but failed trials (M = 1.3% trials failed, SD = 3.50). This results from several task design characteristics aimed at preventing subjects from failing accepted trials, to avoid confounding of effort discounting with risk discounting.”

“3.3 Exertion of “extra effort”

We also explored the extent to which participants went “above and beyond” the target in accepted trials. Specifically, considering only accepted and succeeded trials, we computed the factor by which the required number of clicks was exceeded (i.e., if a subject clicked 15 times when 10 clicks were required the factor would be 1.3), averaging across effort and reward level. We then conducted a Bayesian GLM to test whether this subject wise click-exceedance measure can be predicted by apathy or anhedonia, controlling for age and gender. We found neither the SHAPS (M=-0.14, 95% HDI=[-0.43,0.17]) nor the AES (M=0.07, 95% HDI=[-0.26,0.41]) had a predictive value for the amount to which subjects exert “extra effort”.”

- Perhaps relatedly, there is evidence that people with depression show less of an optimism bias in their predictions about future outcomes. As such, they show more "rational" choices in probabilistic decision tasks. I'm curious whether the Authors think that a weaker choice bias among those with stronger depression/anhedonia/apathy might be related. Also, are choices better matched with actual effort production among those with depression?

We think this is a very interesting comment, but unfortunately feel our manuscript cannot properly speak to it: as in our response to the previous comment, our exploratory analysis linking the proportion of accepted but failed trials to anhedonia symptoms (i.e. less anhedonic people making more optimistic judgments of their likelihood of success) did not show a relationship between the two. However, this null finding may be the result of our task design which is not laid out to capture such an effect (in fact to minimize trials of this nature). We have added to the Discussion section.

Lines 442 – 445:

“It is possible that a higher motivational tendency reflects a more optimistic assessment of future task success, in line with work on the optimism bias95; however our task intentionally minimized unsuccessful trials by titrating effort and reward; future studies should explore this more directly.

(95) Korn, C. W., Sharot, T., Walter, H., Heekeren, H. R. & Dolan, R. J. Depression is related to an absence of optimistically biased belief updating about future life events. Psychological Medicine 44, 579–592 (2014).”

- The manuscript does not clarify: How did the Authors ensure that each subject received each effort-reward combination at least once if a given subject always accepted or always rejected offers?

We have made the following edit to the Methods section to better explain this aspect of our task design.

Lines 642 – 655:

“For each subject, trial-by-trial presentation of effort-reward combinations were made semi-adaptively by 16 randomly interleaved staircases. Each of the 16 possible offers (4 effort-levels x 4 reward-levels) served as the starting point of one of the 16 staircase. Within each staircase, after a subject accepted a challenge, the next trial’s offer on that staircase was adjusted (by increasing effort or decreasing reward). After a subject rejected a challenge, the next offer on that staircase was adjusted by decreasing effort or increasing reward. This ensured subjects received each effort-reward combination at least once (as each participant completed all 16 staircases), while individualizing trial presentation to maximize the trials’ informative value. Therefore, in practice, even in the case of a subject rejecing all offers (and hence the staircasing procedures always adapting by decreasing effort or increasing reward), the full range of effort-reward combinations will be represented in the task across the startingpoints of all staircases (and therefore before adaption takeplace).”

- The word "metabolic" is misspelled in Table 1

- Figure 2 is missing panel label "C"

- The word "effort" is repeated on line 448.

We thank the Reviewer for their attentive reading of our manuscript and have corrected the mistakes mentioned.

Reviewer #3 (Recommendations For The Authors):

It is a bit difficult to get a sense of people's discounting from the plots provided. Could the authors show a few example individuals and their fits (i.e., how steep was effort discounting on average and how much variance was there across individuals; maybe they could show the mean discount function or some examples etc)

We appreciate very much the Reviewer's suggestion to visualise our parameter estimates within and across individuals. We have implemented this in Figure .S2

It would be helpful if correlations between the various markers used as dependent variables (SHAPS, DARS, AES, chronotype etc) could plotted as part of each related figure (e.g., next to the relevant effects shown).

We agree with the Reviewer that a visual representation of the various correlations between dependent variables would be a better and more assessable communication than our current paragraph listing the correlations. We have implemented this by adding a new figure plotting all correlations in a heat map, with asterisks indicating significance.

The authors use the term "meaningful relationship" - how is this defined? If undefined, maybe consider changing (do they mean significant?)

We understand how our use of the term “(no) meaningful relationship” was confusing here. As we conducted most analyses in a Bayesian fashion, this is a formal definition of ‘meaningful’: the 95% highest density interval does not span across 0. However, we do not want this to be misunderstood as frequentist “significance” and agree clarity can be improved here, To avoid confusion, we have amended the manuscript where relevant (i.e., we now state “we found a (/no) relationship / effect” rather than “we found a meaningful relationship”.

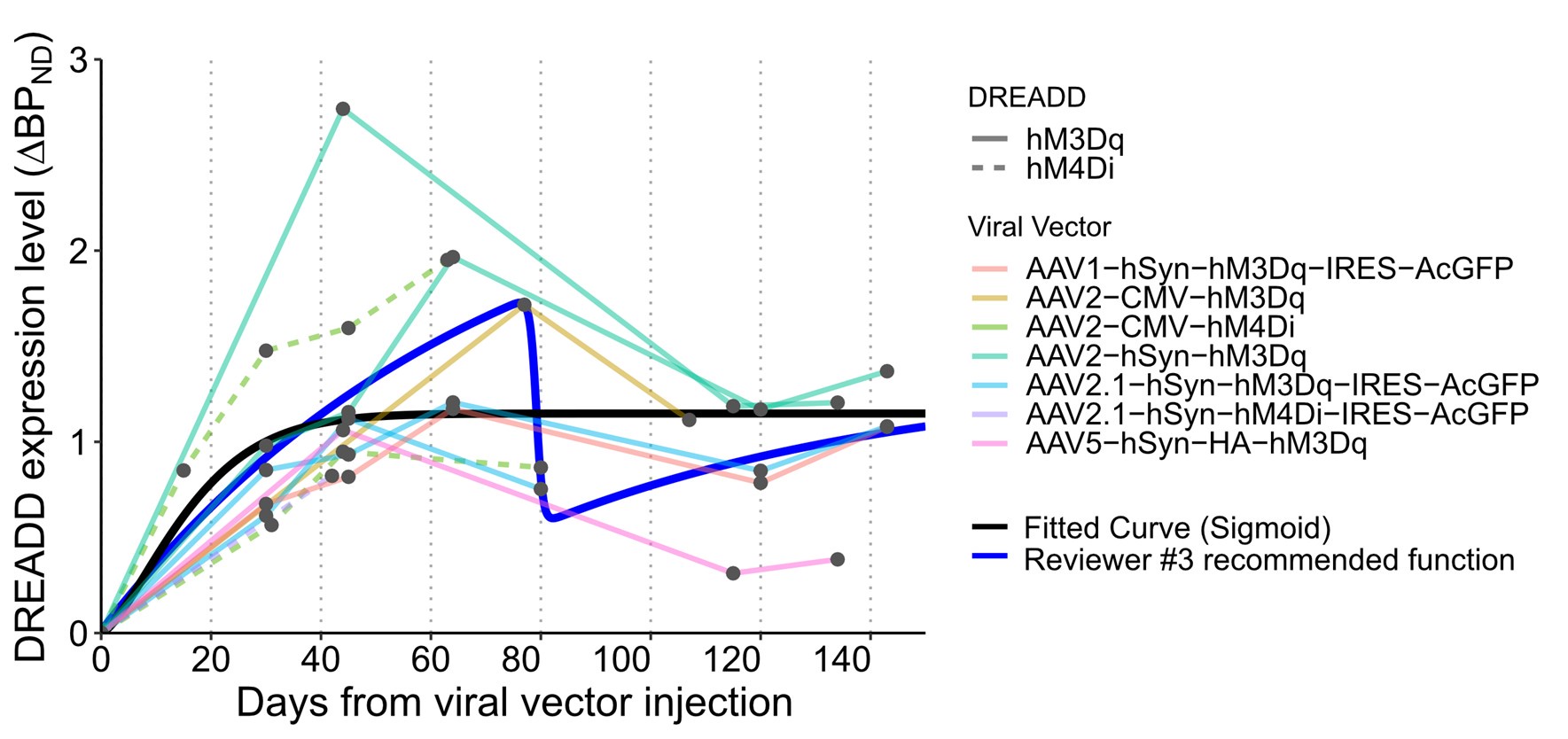

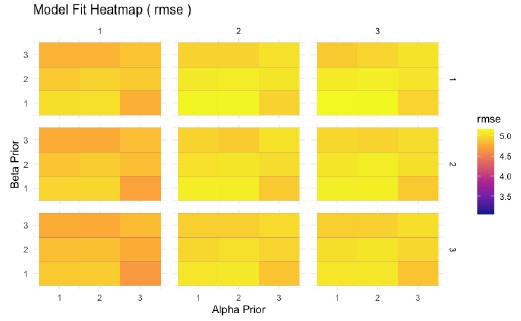

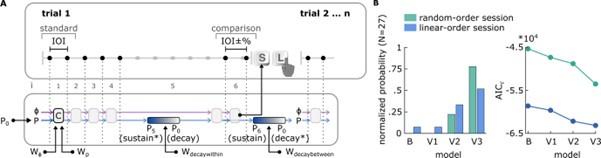

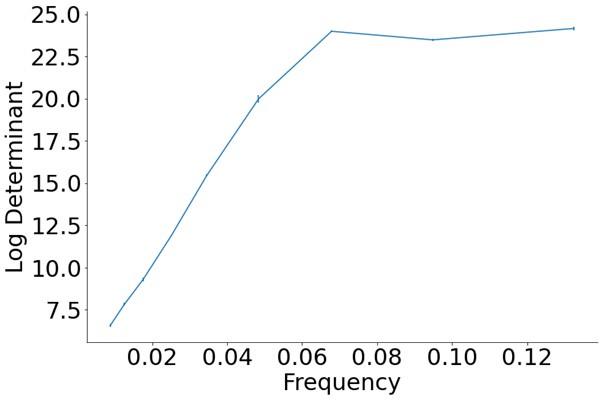

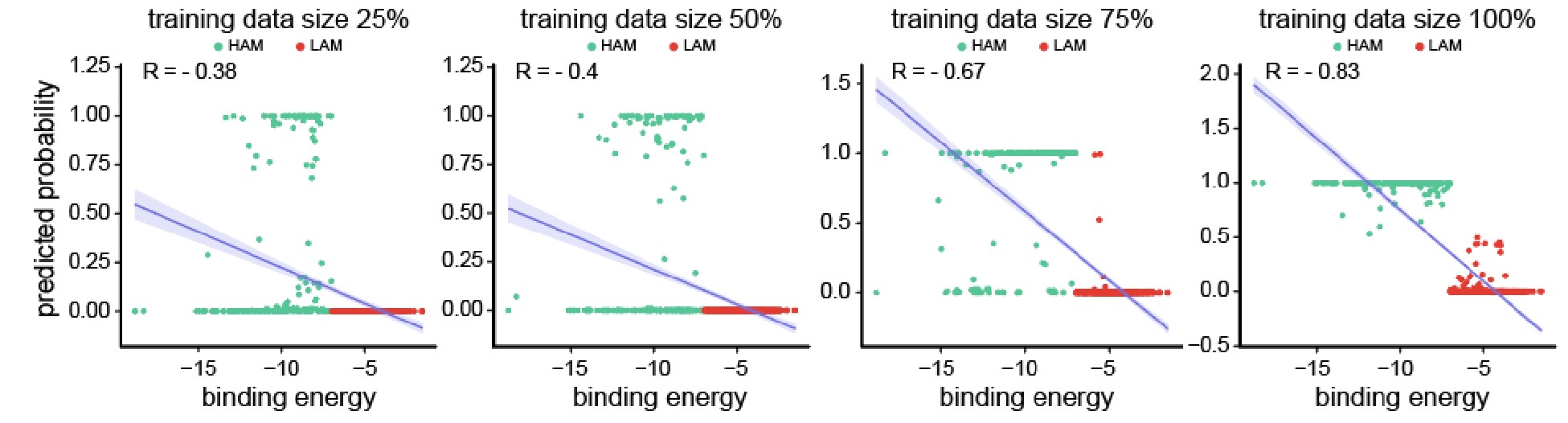

The authors do not include an inverse temperature parameter in their discounting models-can they motivate why? If a participant chose nearly randomly, which set of parameter values would they get assigned?

Our decision to not include an inverse temperature parameter was made after an extensive simulation-based investigation of different models and task designs. A series of parameter recovery studies including models with an inverse temperature parameter revealed the inverse temperature parameter could not be distinguished from the reward sensitivity parameter. Specifically, inverse temperature seemed to capture the variance of the true underlying reward sensitivity parameter, leading to confounding between the two. Hence, including both reward sensitivity and inverse temperature would not have allowed us to reliably estimate either parameter. As our pre-registered hypotheses related to the reward sensitivity parameter, we opted to include models with the reward sensitivity parameter rather than the inverse temperature parameter in our model space. We have now added these simulations to our supplement.

Nevertheless, we believe our models can capture random decision-making. The parameters of effort and reward sensitivity capture how sensitive one is to changes in effort/reward level. Hence, random decision-making can be interpreted as low effort and reward sensitivity, such that one’s decision-making is not guided by changes in effort and reward magnitude. With low effort/reward sensitivity, the motivational tendency parameter (previously “choice bias”) would capture to what extend this random decision-making is biased toward accepting or rejecting offers.

The simulation results are now detailed in the Supplement.

Lines 25 – 46:

“1.2.1 Parameter recoveries including inverse temperature

In the process of task and model space development, we also considered models incorportating an inverse temperature paramater. To this end, we conducted parameter recoveries for four models, defined in Table S3.

Parameter recoveries indicated that, parameters can be recovered reliably in model 1, which includes only effort sensitivity (  ) and inverse temperature

) and inverse temperature  as free parameters (on-diagonal correlations: .98 > r > .89, off-diagonal correlations: .04 > |r| > .004). However, as a reward sensitivity parameter is added to the model (model 2), parameter recovery seems to be compromised, as parameters are estimated less accurately (on-diagonal correlations: .80 > r > .68), and spurious correlations between parameters emerge (off-diagonal correlations: .40 > |r| > .17). This issue remains when motivational tendency is added to the model (model 4; on-diagonal correlations: .90 > r > .65; off-diagonal correlations: .28 > |r| > .03), but not when inverse temperature is modelled with effort sensitivity and motivational tendency, but not reward sensitivity (model 3; on-diagonal correlations: .96 > r > .73; off-diagonal correlations: .05 > |r| > .003).

as free parameters (on-diagonal correlations: .98 > r > .89, off-diagonal correlations: .04 > |r| > .004). However, as a reward sensitivity parameter is added to the model (model 2), parameter recovery seems to be compromised, as parameters are estimated less accurately (on-diagonal correlations: .80 > r > .68), and spurious correlations between parameters emerge (off-diagonal correlations: .40 > |r| > .17). This issue remains when motivational tendency is added to the model (model 4; on-diagonal correlations: .90 > r > .65; off-diagonal correlations: .28 > |r| > .03), but not when inverse temperature is modelled with effort sensitivity and motivational tendency, but not reward sensitivity (model 3; on-diagonal correlations: .96 > r > .73; off-diagonal correlations: .05 > |r| > .003).

As our pre-registered hypotheses related to the reward sensitivity parameter, we opted to include models with the reward sensitivity parameter rather than the inverse temperature parameter in our model space.”

And we now discuss random decision-making specifically in the Methods section.

Lines 698 – 709:

“First, a cost function transforms costs and rewards associated with an action into a subjective value (SV):

with  and

and  for reward and effort sensitivity, and and for reward and effort. Higher effort and reward sensitivity mean the SV is more strongly influenced by changes in effort and reward, respectively (Fig. 3B-C). Hence, low effort and reward sensitivity mean the SV, and with that decision-making, is less guided by effort and reward offers, as would be in random decision-making.

for reward and effort sensitivity, and and for reward and effort. Higher effort and reward sensitivity mean the SV is more strongly influenced by changes in effort and reward, respectively (Fig. 3B-C). Hence, low effort and reward sensitivity mean the SV, and with that decision-making, is less guided by effort and reward offers, as would be in random decision-making.

This SV is then transformed to an acceptance probability by a softmax function:

with  for the predicted acceptance probability and for the intercept representing motivational tendency. A high motivational tendency means a subjects has a tendency, or bias, to accept rather than reject offers (Fig. 3D).”

for the predicted acceptance probability and for the intercept representing motivational tendency. A high motivational tendency means a subjects has a tendency, or bias, to accept rather than reject offers (Fig. 3D).”

The pre-registration mentions effects of BMI and risk of metabolic disease-those are briefly reported the in factor loadings, but not discussed afterwards-although the authors stated hypotheses regarding these measures in their preregistration. Were those hypotheses supported?

We reported these results (albeit only briefly) in the factor loadings resulting from our PLS regression and results from follow-up GLMs (see below). We have now amended the Discussion to enable further elaboration on whether they confirmed our hypotheses (this evidence was unclear, but we have subsequently followed up in a sample with type-2 diabetes, who also show reduced motivational tendency).

Lines 258 – 261:

“For the MEQ (95%HDI=[-0.09,0.06]), MCTQ (95%HDI=[-0.17,0.05]), BMI (95%HDI=[-0.19,0.01]), and FINDRISC (95%HDI=[-0.09,0.03]) no relationship with motivational tendency was found, consistent with the smaller magnitude of reported component loadings from the PLS regression.”

We have added the following paragraph to our discussion.

Lines 491 – 502:

“To our surprise, we did not find statistical evidence for a relationship between effort-based decision-making and measures of metabolic health (BMI and risk for type-2 diabetes). Our analyses linking BMI to motivational tendency reveal a numeric effect in line with our hypothesis: a higher BMI relating to a lower motivational tendency. However, the 95% HDI for this effect narrowly included zero (95%HDI=[-0.19,0.01]). Possibly, our sample did not have sufficient variance in metabolic health to detect dimensional metabolic effects in a current general population sample. A recent study by our group investigates the same neurocomputational parameters of effort-based decision-making in participants with type-2 diabetes and non-diabetic controls matched by age, gender, and physical activity105. We report a group effect on the motivational tendency parameter, with type-2 diabetic patients showing a lower tendency to exert effort for reward.”

“(105) Mehrhof, S. Z., Fleming, H. A. & Nord, C. A cognitive signature of metabolic health in effort-based decision-making. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/4bkm9 (2024).”

R-values are indicated as a range (e.g., from 0.07-0.72 for the last one in 2.1 which is a large range). As mentioned above, the full correlation matrix should be reported in figures as heatmaps.

We agree with the Reviewer that a heatmap is a better way of conveying this information – see Figure 1 in response to their previous comment.

The answer on whether data was already collected is missing on the second preregistration link. Maybe this is worth commenting on somewhere in the manuscript.

This question appears missing because, as detailed in the manuscript, we felt that technically some data *was* already collected by the time our second pre-registration was posted. This is because the second pre-registration detailed an additional data collection, with the goal of extending data from the original dataset to include extreme chronotypes and increase precision of analyses. To avoid any confusion regarding the lack of reply to this question in the pre-registration, we have added the following disclaimer to the description of the second pre-registration:

“Please note the lack of response to the question regarding already collected data. This is because the data collection in the current pre-registration extends data from the original dataset to increase the precision of analyses. While this original data is already collected, none of the data collection described here has taken place.”

Some referencing is not reflective of the current state of the field (e.g., for effort discounting: Sugiwaka et al., 2004 is cited). There are multiple labs that have published on this since then including Philippe Tobler's and Sven Bestmann's groups (e.g., Hartmann et al., 2013; Klein-Flügge et al., Plos CB, 2015).

We agree absolutely, and have added additional, more recent references on effort discounting.

Lines 67 – 68:

“Higher costs devalue associated rewards, an effect referred to as effort-discounting33–37.”

(33) Sugiwaka, H. & Okouchi, H. Reformative self-control and discounting of reward value by delay or effort1. Japanese Psychological Research 46, 1–9 (2004).

(34) Hartmann, M. N., Hager, O. M., Tobler, P. N. & Kaiser, S. Parabolic discounting of monetary rewards by physical effort. Behavioural Processes 100, 192–196 (2013).

(35) Klein-Flügge, M. C., Kennerley, S. W., Saraiva, A. C., Penny, W. D. & Bestmann, S. Behavioral Modeling of Human Choices Reveals Dissociable Effects of Physical Effort and Temporal Delay on Reward Devaluation. PLOS Computational Biology 11, e1004116 (2015).

(36) Białaszek, W., Marcowski, P. & Ostaszewski, P. Physical and cognitive effort discounting across different reward magnitudes: Tests of discounting models. PLOS ONE 12, e0182353 (2017).

(37) Ostaszewski, P., Bąbel, P. & Swebodziński, B. Physical and cognitive effort discounting of hypothetical monetary rewards. Japanese Psychological Research 55, 329–337 (2013).

There are lots of typos throughout (e.g., Supplementary martial, Mornignness etc)

We thank the Reviewer for their attentive reading of our manuscript and have corrected our mistakes.

In Table 1, it is not clear what the numbers given in parentheses are. The figure note mentions SD, IQR, and those are explicitly specified for some rows, but not all.

After reviewing Table 1 we understand the comment regarding the clarity of the number in parentheses. In our original manuscript, for some variables, numbers were given per category (e.g. for gender and ethnicity), rather than per row, in which case the parenthetical statistic was indicated in the header row only. However, we now see that the clarity of the table would have been improved by adding the reported statistic for each row—we have corrected this.

In Figure 1C, it would be much more helpful if the different panels were combined into one single panel (using differently coloured dots/lines instead of bars).

We agree visualizing the proportion of accepted trials across effort and reward levels in one single panel aids interpretability. We have implemented it in the following plot (now Figure 2C).

In Sections 2.2.1 and 4.2.1, the authors mention "mixed-effects analysis of variance (ANOVA) of repeated measures" (same in the preregistration). It is not clear if this is a standard RM-ANOVA (aggregating data per participant per condition) or a mixed-effects model (analysing data on a trial-by-trial level). This model seems to only include within-subjects variable, so it isn't a "mixed ANOVA" mixing within and between subjects effects.

We apologise that our use of the term "mixed-effects analysis of variance (ANOVA) of repeated measures" is indeed incorrectly applied here. We aggregate data per participant and effort-by-reward combination, meaning there are no between-subject effects tested. We have corrected this to “repeated measures ANOVA”.

In Section 2.2.2, the authors write "R-hats>1.002" but probably mean "R-hats < 1.002". ESS is hard to evaluate unless the total number of samples is given.

We thank the Reviewer for noticing this mistake and have corrected it in the manuscript.

In Section 2.3, the inference criterion is unclear. The authors first report "factor loadings" and then perform a permutation test that is not further explained. Which of these factors are actually needed for predicting choice bias out of chance? The permutation test suggests that the null hypothesis is just "none of these measures contributes anything to predicting choice bias", which is already falsified if only one of them shows an association with choice bias. It would be relevant to know for which measures this is the case. Specifically, it would be relevant to know whether adding circadian measures into a model that already contains apathy/anhedonia improves predictive performance.

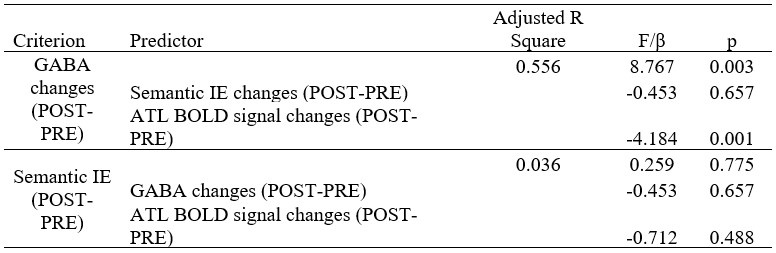

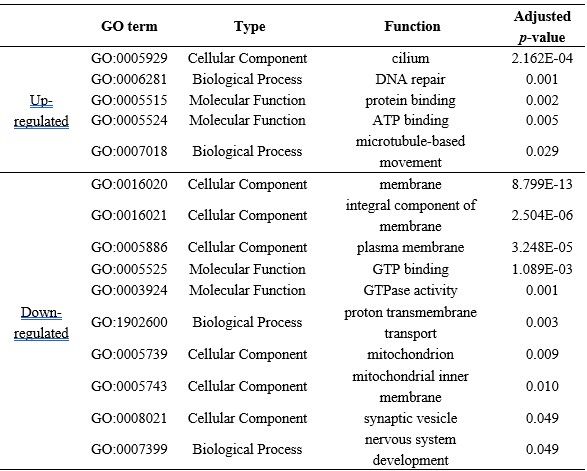

We understand the Reviewer’s concerns regarding the detail of explanation we have provided for this part of our analysis, but we believe there may have been a misunderstanding regarding the partial least squares (PLS) regression. Rather than identifying a number of factors to predict the outcome variable, a PLS regression identifies a model with one or multiple components, with various factor loadings of differing magnitude. In our case, the PLS regression identified a model with one component to best predict our outcome variable (motivational tendency, which in our previous various we called choice bias). This one component had factor loadings of our questionnaire-based measures, with measures of apathy and anhedonia having highest weights, followed by lesser weighted factor loadings by measures of circadian rhythm and metabolic health. The permutation test tests whether this component (consisting of the combination of factor loadings) can predict the outcome variable out of sample.

We hope we have improved clarity on this in the manuscript by making the following edits to the Results section.

Lines 248 – 251:

“Permutation testing indicated the predictive value of the resulting component (with factor loadings described above) was significant out-of-sample (root-mean-squared error [RMSE]=0.203, p=.001).”

Further, we hope to provide a more in-depth explanation of these results in the Methods section.

Lines 755 – 759:

“Statistical significance of obtained effects (i.e., the predictive accuracy of the identified component and factor loadings) was assessed by permutation tests, probing the proportion of root-mean-squared errors (RMSEs) indicating stronger or equally strong predictive accuracy under the null hypothesis.”

In Section 2.5, the authors simply report "that chronotype showed effects of chronotype on reward sensitivity", but the direction of the effect (higher reward sensitivity in early vs. late chronotype) remains unclear.

We thank the Reviewer for pointing this out. While we did report the direction of effect, this was only presented in the subsequent parentheticals and could have been made much clearer. To assist with this, we have made the following addition to the text.

Lines 317 – 320:

“Bayesian GLMs, controlling for age and gender, predicting task parameters by time-of-day and chronotype showed effects of chronotype on reward sensitivity (i.e. those with a late chronotype had a higher reward sensitivity; M= 0.325, 95% HDI=[0.19,0.46])”

In Section 4.2, the authors write that they "implemented a previously-described procedure using Prolific pre-screeners", but no reference to this previous description is given.

We thank the Reviewer for bringing our attention to this missing reference, which has now been added to the manuscript.

In Supplementary Table S2, only the "on-diagonal correlations" are given, but off-diagonal correlations (indicative of trade-offs between parameters) would also be informative.

We agree with the Reviewer that off-diagonal correlations between underlying and recovered parameters are crucial to assess confounding between parameters during model estimation. We reported this in figure S1D, where we present the full correlation matric between underlying and recovered parameters in a heatmap. We have now noticed that this plot was missing axis labels, which have been added now.

I found it somewhat difficult to follow the results section without having read the methods section beforehand. At the beginning of the Results section, could the authors briefly sketch the outline of their study? Also, given they have a pre-registration, could the authors introduce each section with a statement of what they expected to find, and close with whether the data confirmed their expectations? In the current version of the manuscript, many results are presented without much context of what they mean.

We agree a brief outline of the study procedure before reporting the results would be beneficial to following the subsequently text and have added the following to the end of our Introduction.

Lines 101 – 106:

“Here, we tested the relationship between motivational decision-making and three key neuropsychiatric syndromes: anhedonia, apathy, and depression, taking both a transdiagnostic and categorical (diagnostic) approach. To do this, we validate a newly developed effort-expenditure task, designed for online testing, and gamified to increase engagement. Participants completed the effort-expenditure task online, followed by a series of self-report questionnaires.”

We have added references to our pre-registered hypotheses at multiple points in our manuscript.

Lines 185 – 187:

“In line with our pre-registered hypotheses, we found significant main effects for effort (F(1,14367)=4961.07, p<.0001) and reward (F(1,14367)=3037.91, p<.001), and a significant interaction between the two (F(1,14367)=1703.24, p<.001).”

Lines 215 – 221:

“Model comparison by out-of-sample predictive accuracy identified the model implementing three parameters (motivational tendency a, reward sensitivity  , and effort sensitivity

, and effort sensitivity  ), with a parabolic cost function (subsequently referred to as the full parabolic model) as the winning model (leave-one-out information criterion [LOOIC; lower is better] = 29734.8; expected log posterior density [ELPD; higher is better] = -14867.4; Fig. 31ED). This was in line with our pre-registered hypotheses.”

), with a parabolic cost function (subsequently referred to as the full parabolic model) as the winning model (leave-one-out information criterion [LOOIC; lower is better] = 29734.8; expected log posterior density [ELPD; higher is better] = -14867.4; Fig. 31ED). This was in line with our pre-registered hypotheses.”

Lines 252 – 258:

“Bayesian GLMs confirmed evidence for psychiatric questionnaire measures predicting motivational tendency (SHAPS: M=-0.109; 95% highest density interval (HDI)=[-0.17,-0.04]; AES: M=-0.096; 95%HDI=[-0.15,-0.03]; DARS: M=-0.061; 95%HDI=[-0.13,-0.01]; Fig. 4A). Post-hoc GLMs on DARS sub-scales showed an effect for the sensory subscale (M=-0.050; 95%HDI=[-0.10,-0.01]). This result of neuropsychiatric symptoms predicting a lower motivational tendency is in line with our pre-registered hypothesis.”

Lines 258 – 263:

“For the MEQ (95%HDI=[-0.09,0.06]), MCTQ (95%HDI=[-0.17,0.05]), BMI (95%HDI=[-0.19,0.01]), and FINDRISC (95%HDI=[-0.09,0.03]) no meaningful relationship with choice biasmotivational tendency was found, consistent with the smaller magnitude of reported component loadings from the PLS regression. This null finding for dimensional measures of circadian rhythm and metabolic health was not in line with our pre-registered hypotheses.”

Lines 268 – 270:

“For reward sensitivity, the intercept-only model outperformed models incorporating questionnaire predictors based on RMSE. This result was not in line with our pre-registered expectations.”

Lines 295 – 298:

“As in our transdiagnostic analyses of continuous neuropsychiatric measures (Results 2.3), we found evidence for a lower motivational tendency parameter in the MDD group compared to HCs (M=-0.111, 95% HDI=[ -0.20,-0.03]) (Fig. 4B). This result confirmed our pre-registered hypothesis.”

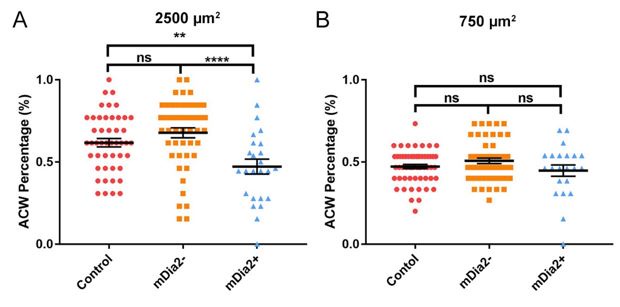

Lines 344 – 355:

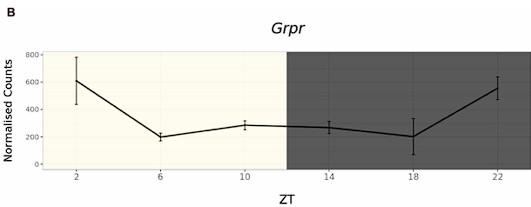

“Late chronotypes showed a lower motivational tendency than early chronotypes (M=-0.11, 95% HDI=[-0.22,-0.02])—comparable to effects of transdiagnostic measures of apathy and anhedonia, as well as diagnostic criteria for depression. Crucially, we found motivational tendency was modulated by an interaction between chronotype and time-of-day (M=0.19, 95% HDI=[0.05,0.33]): post-hoc GLMs in each chronotype group showed this was driven by a time-of-day effect within late, rather than early, chronotype participants (M=0.12, 95% HDI=[0.02,0.22], such that late chronotype participants showed a lower motivational tendency in the morning testing sessions, and a higher motivational tendency in the evening testing sessions; early chronotype: 95% HDI=[-0.16,0.04]) (Fig. 5A). These results of a main effect and an interaction effect of chronotype on motivational tendency confirmed our pre-registered hypothesis.”

Lines 390 – 393:

“Participants with an early chronotype had a lower reward sensitivity parameter than those with a late chronotype (M=0.27, 95% HDI=[0.16,0.38]). We found no effect of time-of-day on reward sensitivity (95%HDI=[-0.09,0.11]) (Fig. 5B). These results were in line with our pre-registered hypotheses.”