maybe computational notebooks will only take root if they’re backed by a single super-language, or by a company with deep pockets and a vested interest in making them work. But it seems just as likely that the opposite is true. A federated effort, while more chaotic, might also be more robust—and the only way to win the trust of the scientific community.

- Jan 2026

-

dbmi7byi6naiyr.archive.is dbmi7byi6naiyr.archive.is

-

-

The Mathematica notebook is the more coherently designed, more polished product—in large part because every decision that went into building it emanated from the mind of a single, opinionated genius. “I see these Jupyter guys,” Wolfram said to me, “they are about on a par with what we had in the early 1990s.” They’ve taken shortcuts, he said. “We actually want to try and do it right.”

Desde mediados/finales de los noventas no uso Mathematica, e incluso en ese momento era un gran sistema, altamente integrado y coherente. Sin embargo, en la medida en que me decanté por el software libre, empecé prontamente a buscar alternativas e inicié con TeXmacs, del cual traduje la mayor parte de su documentación al español, como una de mis primeras contribuciones a un proyecto de software libre (creo que aún la traducción es la que se está usando y por aquella época usábamos SVN para coordinar cambio e incluso enviábamos archivos compresos, pues el control de versiones no era muy popular).Por ejemplo el bonito y minimalista Yacas, con el que hiciera muchas de mis tareas en pregrado y colocara algunos talleres y corrigiría parciales cuando me convirtiese en profesor del departamento de Matemáticas

TeXmacs, a diferencia de sistemas monolíticos como Mathematica, se conectaba ya desde ese entonces con una gran variedad de Sistemas de Álgebra Computacional (o CAS, por sus siglas en inglés) exponiéndonos a una diversidad de enfoques y paradigmas CAS, con sus sintaxis e idiosincracias particulares, en una riqueza que Mathematica nunca tendrá.

TeXmacs también me expondría a ideas poderosas, como poder cambiar el software fácilmente a partir de pequeños scripts (en Scheme), que lo convirtieron en el primer software libre que modifiqué, y las poderosas S-expressions que permitían definir un documento y su interacción con CAS externos, si bien TeXmas ofrecía un lenguaje propio mas legible y permitía pasar de Scheme a este y viceversa.

En general esa es la diferencia de los sistemas privativos con los libres: una monocultura versus una policultura, con las conveniencias de la primera respecto a los enfoques unificantes contra la diversidad de la segunda. Si miramos lo que ha ocurrido con Python y las libretas computacionales abiertas como Marimo y Jupyter, estos han ganado en la conciencia popular con respecto a Mathematica y han incorporado funcionalidad progresiva que Mathematica tenía, mientras que otra sigue estando aún presente en los sistemas privativos y no en los libres y viceversa. Yo no diría que las libretas computacionales libres están donde estaba Mathematica en los 90's, sino que han seguido rutas históricas diferentes, cada una con sus valores y riquezas.

-

“I think what they have is acceptance from the scientific community as a tool that is considered to be universal,” Theodore Gray says of Pérez’s group. “And that’s the thing that Mathematica never really so far has achieved.” There are now 1.3 million of these notebooks hosted publicly on Github. They’re in use at Google, Bloomberg, and NASA; by musicians, teachers, and AI researchers; and in “almost every country on Earth.”

-

Out of the box, Python is a much less powerful language than the Wolfram Language that powers Mathematica. But where Mathematica gets its powers from an army of Wolfram Research programmers, Python’s bare-bones core is supplemented by a massive library of extra features—for processing images, making music, building AIs, analyzing language, graphing data sets—built by a community of open-source contributors working for free. Python became a de facto standard for scientific computing because open-source developers like Pérez happened to build useful tools for it; and open-source developers have flocked to Python because it happens to be the de facto standard for scientific computing. Programming-language communities, like any social network, thrive—or die—on the strength of these feedback loops.

-

In early 2001, Fernando Pérez found himself in much the same position Wolfram had 20 years earlier: He was a young graduate student in physics running up against the limits of his tools. He’d been using a hodgepodge of systems, Mathematica among them, feeling as though every task required switching from one to the next. He remembered having six or seven different programming-language books on his desk. What he wanted was a unified environment for scientific computing.

Como he documentado en mi blog, antes de Grafoscopio, mis primeros intentos por crear flujos y herramientas de documentación interactiva a medida fueron en IPython, pero me cansé de lidiar con la complejidad incidental del stack con el que IPython y luego Jupyter estaban hechos, encontrando en Pharo Smalltalk una plataforma más coherente, simple, entendible y adaptable.

Como he explicado en otros apartados, si bien Grafoscopio mezcla herramientas distintas de nuestros flujos de documentación y publicación, ahora Cardumem surge con la idea de crear una interfaz web y una experiencia unificada para las integraciones, con una sintaxis minimalista y sin los requerimientos conceptuales de la programación orientada a objetos.

-

- Dec 2023

-

datasciencenotebook.org datasciencenotebook.org

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

- Oct 2023

- May 2023

-

stackoverflow.com stackoverflow.com

-

Host machine: docker run -it -p 8888:8888 image:version Inside the Container : jupyter notebook --ip 0.0.0.0 --no-browser --allow-root Host machine access this url : localhost:8888/tree

3 ways of running

jupyter notebookin a container

-

-

notebooks.vires.services notebooks.vires.services

-

Seems a useful description of what Jupyter books are.

-

- Jan 2023

- Dec 2022

-

www.complexityexplorer.org www.complexityexplorer.org

- Nov 2022

-

test-nbdime.readthedocs.io test-nbdime.readthedocs.io

-

test-nbdime.readthedocs.io test-nbdime.readthedocs.io

- Oct 2022

-

www.loom.com www.loom.com

-

https://www.loom.com/share/a05f636661cb41628b9cb7061bd749ae

Synopsis: Maggie Delano looks at some of the affordances supplied by Tana (compared to Roam Research) in terms of providing better block-based user interface for note type creation, search, and filtering.

These sorts of tools and programmable note implementations remind me of Beatrice Webb's idea of scientific note taking or using her note cards like a database to sort and search for data to analyze it and create new results and insight.

It would seem that many of these note taking tools like Roam and Tana are using blocks and sub blocks as a means of defining atomic notes or database-like data in a way in which sub-blocks are linked to or "filed underneath" their parent blocks. In reality it would seem that they're still using a broadly defined index card type system as used in the late 1800s/early 1900s to implement a set up that otherwise would be a traditional database in the Microsoft Excel or MySQL sort of fashion, the major difference being that the user interface is cognitively easier to understand for most people.

These allow people to take a form of structured textual notes to which might be attached other smaller data or meta data chunks that can be easily searched, sorted, and filtered to allow for quicker or easier use.

Ostensibly from a mathematical (or set theoretic and even topological) point of view there should be a variety of one-to-one and onto relationships (some might even extend these to "links") between these sorts of notes and database representations such that one should be able to implement their note taking system in Excel or MySQL and do all of these sorts of things.

Cascading Idea Sheets or Cascading Idea Relationships

One might analogize these sorts of note taking interfaces to Cascading Style Sheets (CSS). While there is the perennial question about whether or not CSS is a programming language, if we presume that it is (and it is), then we can apply the same sorts of class, id, and inheritance structures to our notes and their meta data. Thus one could have an incredibly atomic word, phrase, or even number(s) which inherits a set of semantic relationships to those ideas which it sits below. These links and relationships then more clearly define and contextualize them with respect to other similar ideas that may be situated outside of or adjacent to them. Once one has done this then there is a variety of Boolean operations which might be applied to various similar sets and classes of ideas.

If one wanted to go an additional level of abstraction further, then one could apply the ideas of category theory to one's notes to generate new ideas and structures. This may allow using abstractions in one field of academic research to others much further afield.

The user interface then becomes the key differentiator when bringing these ideas to the masses. Developers and designers should be endeavoring to allow the power of complex searches, sorts, and filtering while minimizing the sorts of advanced search queries that an average person would be expected to execute for themselves while also allowing some reasonable flexibility in the sorts of ways that users might (most easily for them) add data and meta data to their ideas.

Jupyter programmable notebooks are of this sort, but do they have the same sort of hierarchical "card" type (or atomic note type) implementation?

Tags

- watch

- card index as database

- Boolean algebra

- super tags

- integrated thinking environments

- cascading idea sheets

- idea links

- Roam Research

- user interface

- types of notes

- category theory

- building blocks

- integrated development environment

- scientific note taking

- CSS

- programmable notes

- Maggie Delano

- Beatrice Webb

- Tana

- Jupyter

Annotators

URL

-

- Aug 2022

-

quarto.org quarto.org

-

Quarto® is an open-source scientific and technical publishing system built on Pandoc

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

- Apr 2022

-

nbconvert.readthedocs.io nbconvert.readthedocs.io

-

jupyter nbconvert --to FORMAT notebook.ipynb

convert jupyter notebook to other format by command

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

- Mar 2022

-

blog.jupyter.org blog.jupyter.org

-

Announcing the new Jupyter Book

-

- Dec 2021

-

quarto.org quarto.org

-

Quarto Basics

-

- May 2021

-

halfanhour.blogspot.com halfanhour.blogspot.com

-

Matrix Algebra with Computational Applications e-book offered by Michigan State University. It's a lovely book, and what stood out about it was the way it used PressBooks for distribution as an open e-book, and how it embedded Jupyter Notebook in with the text.

example of a OER textbook with an embedded Jupyter Notebook. I've wanted to noodle around with this myself.

-

- Mar 2021

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

I don't like notebooks.- Joel Grus (Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence)

Because it teaches scientists bad programming habits:

- no modularity (but result depend on order of evaluation)

- no testabilty

- cannot view code without opening jupyter

- missing history (ok

%historyworks)

-

- Feb 2021

-

the-turing-way.netlify.com the-turing-way.netlify.comWelcome1

- Jan 2021

-

towardsdatascience.com towardsdatascience.com

-

Did you know that everything you can do in VBA can also be done in Python? The Excel Object Model is what you use when writing VBA, but the same API is available in Python as well.See Python as a VBA Replacement from the PyXLL documentation for details of how this is possible.

We can replace VBA with Python

-

You can write Excel worksheet functions in your Jupyter notebook too. This is a really great way of trying out ideas without leaving Excel to go to a Python IDE.

We can define functions in Python to later use in Excel

-

Use the magic function “%xl_get” to get the current Excel selection in Python. Have a table of data in Excel? Select the top left corner (or the whole range) and type “%xl_get” in your Jupyter notebook and voila! the Excel table is now a pandas DataFrame.

%xl_getlets us get the current Excel selection in Python -

to run Python code in Excel you need the PyXLL add-in. The PyXLL add-in is what lets us integrate Python into Excel and use Python instead of VBA

PyXLL lets us use Python/Jupyter Notebooks in Excel

-

- Oct 2020

-

datarevenue.com datarevenue.com

-

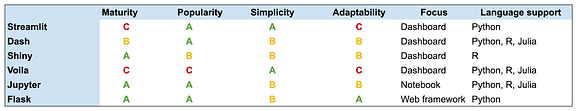

Here’s a table showing the tradeoffs:

Comparison of dashboard tech stack as of 10/2020:

-

- Sep 2020

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

- May 2020

-

medium.com medium.com

-

Hot Reloading refers to the ability to automatically update a running web application when changes are made to the application’s code.

Hot Reloading is what provides a great experience with updating your Dash code inside the Jupyter Notebooks

-

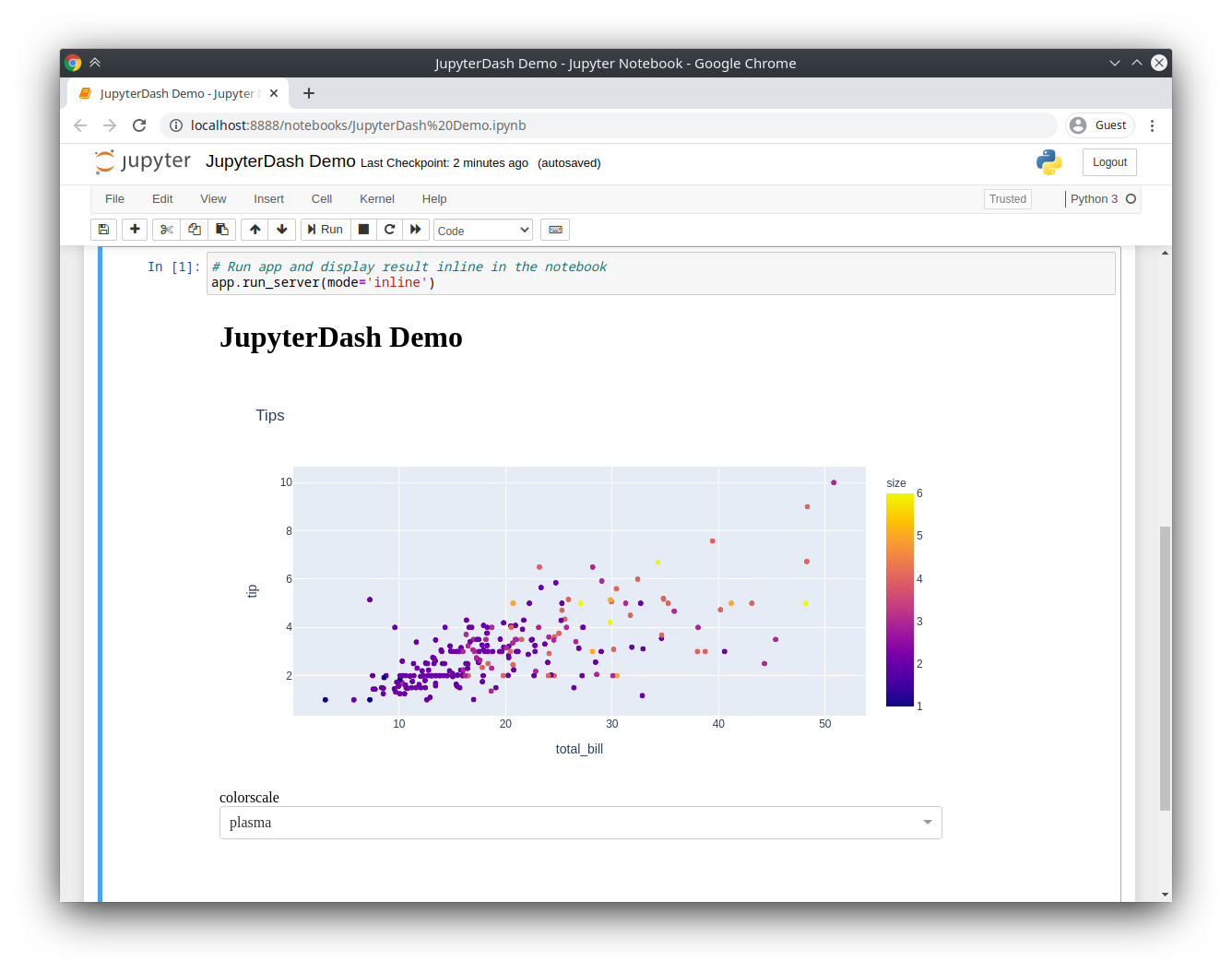

JupyterDash supports three approaches to displaying a Dash application during interactive development.

3 display modes of Dash using Jupyter Notebooks:

- app.run_server(mode='external')

- app.run_server(mode='inline')

- app.run_server(mode='jupyterlab')

-

# Run app and display result inline in the notebookapp.run_server(mode='inline')

Moreover, you can display your Dash result inside a Jupyter Notebook using

IPython.display.IFramewith this line:app.run_server(mode='inline')

-

If running the server blocks the main thread, then it’s not possible to execute additional code cells without manually interrupting the execution of the kernel.JupyterDash resolves this problem by executing the Flask development server in a background thread. This leaves the main execution thread available for additional calculations. When a request is made to serve a new version of the application on the same port, the currently running application is automatically shut down first. This makes is possible to quickly update a running application by simply re-executing the notebook cells that define it.

How Dash can run inside Jupyter Notebooks

-

You can also try it out, right in your browser, with binder.

Dash can be tried out inside a Jupyter Notebook right in your browser using binder.

-

Then, copy any Dash example into a Jupyter notebook cell and replace the dash.Dash class with the jupyter_dash.JupyterDash class.

To use Dash in Jupyter Notebooks, you have to import:

from jupyter_dash import JupyterDashinstead of:

import dashTherefore, all the imports could look like that for a typical Dash app inside a Jupyter Notebook:

import plotly.express as px from jupyter_dash import JupyterDash import dash_core_components as dcc import dash_html_components as html from dash.dependencies import Input, Output

-

-

towardsdatascience.com towardsdatascience.com

-

For many data scientists, the finished product of a work session is a business analysis. They need to show team members—who oftentimes aren’t technical—how their data became a specific recommendation or insight.

Usual final product in Data Science is the business analysis which is perfectly explained with notebooks

-

- Apr 2020

-

www.fast.ai www.fast.ai

-

Development Pros Cons

Table comparing pros and cons of:

- IDE/Editor

- REPL/shell

- Traditional notebooks (like Jupyter)

-

This kind of “exploring” is easiest when you develop on the prompt (or REPL), or using a notebook-oriented development system like Jupyter Notebooks

It's easier to explore the code:

- when you develop on the prompt (or REPL)

- in notebook-oriented system like Jupyter

but, it's not efficient to develop in them

-

notebook contains an actual running Python interpreter instance that you’re fully in control of. So Jupyter can provide auto-completions, parameter lists, and context-sensitive documentation based on the actual state of your code

Notebook makes it easier to handle dynamic Python features

-

They switch to get features like good doc lookup, good syntax highlighting, integration with unit tests, and (critically!) the ability to produce final, distributable source code files, as opposed to notebooks or REPL histories

Things missed in Jupyter Notebooks:

- good doc lookup

- good syntax highlighting

- integration with unit tests

- ability to produce final, distributable source code files

-

Exploratory programming is based on the observation that most of us spend most of our time as coders exploring and experimenting

In exploratory programming, we:

- experiment with a new API to understand how it works

- explore the behavior of an algorithm that we're developing

- debug our code through combination of inputs

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

towardsdatascience.com towardsdatascience.com

-

Version control is at the heart of any modern engineering org. The ability for multiple engineers to asynchronously contribute to a codebase is crucial—and with notebooks, it’s very hard.

Version control in notebooks?

-

Reproducibility is an issue with notebooks. Because of the hidden state and the potential for arbitrary execution order, generating a result in a notebook isn’t always as simple as clicking “Run All.”

Problem of reproducibility in notebooks

-

A notebook, at a very basic level, is just a bunch of JSON that references blocks of code and the order in which they should be executed.But notebooks prioritize presentation and interactivity at the expense of reproducibility. YAML is the other side of that coin, ignoring presentation in favor of simplicity and reproducibility—making it much better for production.

Summary of the article:

Notebook = presentation + interactivity

YAML = simplicity + reproducibility

-

Notebook files, however, are essentially giant JSON documents that contain the base-64 encoding of images and binary data. For a complex notebook, it would be extremely hard for anyone to read through a plaintext diff and draw meaningful conclusions—a lot of it would just be rearranged JSON and unintelligible blocks of base-64.

Git traces plaintext differences and with notebooks it's a problem

-

There is no hidden state or arbitrary execution order in a YAML file, and any changes you make to it can easily be tracked by Git

In comparison to notebooks, YAML is more compatible for Git and in the end might be a better solution for ML

-

Python unit testing libraries, like unittest, can be used within a notebook, but standard CI/CD tooling has trouble dealing with notebooks for the same reasons that notebook diffs are hard to read.

unittest Python library doesn't work well in a notebook

-

-

code.visualstudio.com code.visualstudio.com

-

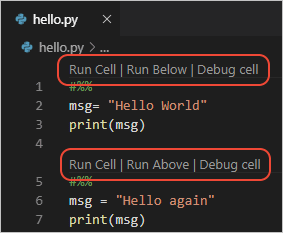

Visual Studio Code supports working with Jupyter Notebooks natively, as well as through Python code files.

To run cells inside a Python script in VSCode, all you need to is to define Jupyter-like code cells within Python code using a

# %%comment:# %% msg = "Hello World" print(msg) # %% msg = "Hello again" print(msg)

-

-

blog.jupyter.org blog.jupyter.org

-

JupyterLab project, which enables a richer UI including a file browser, text editors, consoles, notebooks, and a rich layout system.

How JupyterLab differs from a traditional notebook

-

- Mar 2020

-

nextjournal.com nextjournal.com

-

Jupytext can be configured to automatically pair a git-friendly file for input data while preserving the output data in the .ipynb file

git-friendly Jupytext options include

- Julia: .jl

- Python: .py

- R: .R

- Markdown: .md

- RMarkdown: .Rmd

- and more!

-

-

www.fast.ai www.fast.ai

-

The point of nbdev is to bring the key benefits of IDE/editor development into the notebook system, so you can work in notebooks without compromise for the entire lifecycle

-

- Jan 2020

-

www.digitalocean.com www.digitalocean.com

-

First sighting of Jupyter Notebook (that I recall).

-

- Sep 2019

- Jul 2019

-

www.dataquest.io www.dataquest.io

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

- May 2019

- Jul 2018

-

elifesciences.org elifesciences.org

-

We want to even go even further and add reproducible elements to JATS documents. We are working together with Stencila on extending Texture to allow both textual narrative and executable code to coexist in one document.

-

- Apr 2018

-

jupyterhub.readthedocs.io jupyterhub.readthedocs.io

-

JupyterHub, a multi-user Hub, spawns, manages, and proxies multiple instances of the single-user Jupyter notebook server.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

mybinder.org mybinder.orgbinder1

-

Turn a GitHub repo into a collection of interactive notebooks

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.pythonanywhere.com www.pythonanywhere.com

-

Host, run, and code Python in the cloud!

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.theatlantic.com www.theatlantic.com

-

At one point, Pérez told me the name Jupyter honored Galileo, perhaps the first modern scientist. The Jupyter logo is an abstracted version of Galileo’s original drawings of the moons of Jupiter. “Galileo couldn’t go anywhere to buy a telescope,” Pérez said. “He had to build his own.”

Cool name/logo story!

-

At every turn, IPython chose the way that was more inclusive, to the point where it’s no longer called “IPython”: The project rebranded itself as “Jupyter” in 2014 to recognize the fact that it was no longer just for Python.

Such an interesting progression!

-

At every turn, IPython chose the way that was more inclusive

Nice to see that decision pay off!

-

- Jan 2018

-

blog.dataart.com blog.dataart.com

- Aug 2017

-

github.com github.com

-

markdown_display_priority

I don't know why or when my annotations will be properly applied.

This is quite confusing. The interface remembers my tag, but not the content of my annotation.

It does not seem to allow the application of an annotation to text inside of an

iframe. This prevents proper testing of hypothes.is as a jupyter notebook annotation tool.In some ways it's great, but the interface and user model could use a lot of work. If it allowed annotations inside

iframes I'd gladly navigate those rough edges. But without that feature it's hard to justify trying to use this for the purpose of annotating notebooks.Hopefully, this can be fixed, in which case I'll edit this annotation to acknowledge that annotation inside

iframes works. That would mean the annotation of Jupyter notebooks would be be a process capable of supporting code review on a notebook via GitHub.

-

-

github.com github.com

-

markdown_display_priority

Unfortunately this is probably the easiest place to apply a hypothes.is annotation. They don't look inside

iframes. So the rendered version of the notebook will not work.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

- Mar 2017

-

github.com github.com

-

Seco, si bien es una implementación del 2004, tiene varias ideas que son similares a las de Grafoscopio de hoy, incluyendo la persistencia de una imagen (ellos usan HyperGraphDB, pero incluso mencionan Smalltalk), el hecho de ser una aplicación de escritorio y la idea de una computación p2p, o la opción de embeber el motor de rendering de un browser o el browser mismo en un ambiente más rico, incluso la inspiración de los notebooks de mathematica.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

- Jan 2017

-

forums.fast.ai forums.fast.ai

-

annotation with jupyter notebook

How to Annotate Jupyter notebook stored online

Tags

Annotators

URL

-