Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

(1) I have to admit that it took a few hours of intense work to understand this paper and to even figure out where the authors were coming from. The problem setting, nomenclature, and simulation methods presented in this paper do not conform to the notation common in the field, are often contradictory, and are usually hard to understand. Most importantly, the problem that the paper is trying to solve seems to me to be quite specific to the particular memory study in question, and is very different from the normal setting of model-comparative RSA that I (and I think other readers) may be more familiar with.

We have revised the paper for clarity at all levels: motivation, application, and parameterization. We clarify that there is a large unmet need for using RSA in a trial-wise manner, and that this approach indeed offers benefits to any team interested in decoding trial-wise representational information linked to a behavioral responses, and as such is not a problem specific to a single memory study.

(2) The definition of "classical RSA" that the authors are using is very narrow. The group around Niko Kriegeskorte has developed RSA over the last 10 years, addressing many of the perceived limitations of the technique. For example, cross-validated distance measures (Walther et al. 2016; Nili et al. 2014; Diedrichsen et al. 2021) effectively deal with an uneven number of trials per condition and unequal amounts of measurement noise across trials. Different RDM comparators (Diedrichsen et al. 2021) and statistical methods for generalization across stimuli (Schütt et al. 2023) have been developed, addressing shortcomings in sensitivity. Finally, both a Bayesian variant of RSA (Pattern component modelling, (Diedrichsen, Yokoi, and Arbuckle 2018) and an encoding model (Naselaris et al. 2011) can effectively deal with continuous variables or features across time points or trials in a framework that is very related to RSA (Diedrichsen and Kriegeskorte 2017). The author may not consider these newer developments to be classical, but they are in common use and certainly provide the solution to the problems raised in this paper in the setting of model-comparative RSA in which there is more than one repetition per stimulus.

We appreciate the summary of relevant literature and have included a revised Introduction to address this bounty of relevant work. While much is owed to these authors, new developments from a diverse array of researchers outside of a single group can aid in new research questions, and should always have a place in our research landscape. We owe much to the work of Kriegeskorte’s group, and in fact, Schutt et al., 2023 served as a very relevant touchpoint in the Discussion and helped to highlight specific needs not addressed by the assessment of the “representational geometry” of an entire presented stimulus set. Principal amongst these needs is the application of trial-wise representational information that can be related to trial-wise behavioral responses and thus used to address specific questions on brain-behavior relationships. We invite the Reviewer to consider the utility of this shift with the following revisions to the Introduction.

Page 3. “Recently, methodological advancements have addressed many known limitations in cRSA. For example, cross-validated distance measures (e.g., Euclidean distance) have improved the reliability of representational dissimilarities in the presence of noise and trial imbalance (Walther et al., 2016; Nili et al., 2014; Diedrichsen et al., 2021). Bayesian approaches such as pattern component modeling (Diedrichsen, Yokoi, & Arbuckle, 2018) have extended representational approaches to accommodate continuous stimulus features or temporal variation. Further, model comparison RSA strategies (Diedrichsen et al., 2021) and generalization techniques across stimuli (Schütt et al., 2023) have improved sensitivity and inference. Nevertheless, a common feature shared across most of improvements is that they require stimuli repetition to examine the representational structure. This requirement limits their ability to probe brain-behavior questions at the level of individual events”.

Page 8. “While several extensions of RSA have addressed key limitations in noise sensitivity, stimulus variance, and modeling (e.g., Diedrichsen et al., 2021; Schütt et al., 2023), our tRSA approach introduces a new methodological step by estimating representational strength at the trial level. This accounts for the multi-level variance structure in the data, affords generalizability beyond the fixed stimulus set, and allows one to test stimulus- or trial-level modulations of neural representations in a straightforward way”.

Page 44. “Despite such prevalent appreciation for the neurocognitive relevance of stimulus properties, cRSA often does not account for the fact that the same stimulus (e.g., “basketball”) is seen by multiple subjects and produces statistically dependent data, an issue addressed by Schütt et al., 2023, who developed cross validation and bootstrap methods that explicitly model dependence across both subjects and stimulus conditions”.

(3) The stated problem of the paper is to estimate "representational strength" in different regions or conditions. With this, the authors define the correlation of the brain RDM with a model RDM. This metric conflates a number of factors, namely the variances of the stimulus-specific patterns, the variance of the noise, the true differences between different dissimilarities, and the match between the assumed model and the data-generating model. It took me a long time to figure out that the authors are trying to solve a quite different problem in a quite different setting from the model-comparative approach to RSA that I would consider "classical" (Diedrichsen et al. 2021; Diedrichsen and Kriegeskorte 2017). In this approach, one is trying to test whether local activity patterns are better explained by representation model A or model B, and to estimate the degree to which the representation can be fully explained. In this framework, it is common practice to measure each stimulus at least 2 times, to be able to estimate the variance of noise patterns and the variance of signal patterns directly. Using this setting, I would define 'representational strength" very differently from the authors. Assume (using LaTeX notation) that the activity patterns $y_j,n$ for stimulus j, measurement n, are composed of a true stimulus-related pattern ($u_j$) and a trial-specific noise pattern ($e_j,n$). As a measure of the strength of representation (or pattern), I would use an unbiased estimate of the variance of the true stimulus-specific patterns across voxels and stimuli ($\sigma^2_{u}$). This estimator can be obtained by correlating patterns of the same stimuli across repeated measures, or equivalently, by averaging the cross-validated Euclidean distances (or with spatial prewhitening, Mahalanobis distances) across all stimulus pairs. In contrast, the current paper addresses a specific problem in a quite specific experimental design in which there is only one repetition per stimulus. This means that the authors have no direct way of distinguishing true stimulus patterns from noise processes. The trick that the authors apply here is to assume that the brain data comes from the assumed model RDM (a somewhat sketchy assumption IMO) and that everything that reduces this correlation must be measurement noise. I can now see why tRSA does make some sense for this particular question in this memory study. However, in the more common model-comparative RSA setting, having only one repetition per stimulus in the experiment would be quite a fatal design flaw. Thus, the paper would do better if the authors could spell the specific problem addressed by their method right in the beginning, rather than trying to set up tRSA as a general alternative to "classical RSA".

At a general level, our approach rests on the premise that there is meaningful information present in a single presentation of a given stimulus. This assumption may have less utility when the research goals are more focused on estimating the fidelity of signal patterns for RSA, as in designs with multiple repetitions. But it is an exaggeration to state that such a trial-wise approach cannot address the difference between “true” stimulus patterns and noise. This trial-wise approach has explicit utility in relating trial-wise brain information to trial-wise behavior, across multiple cognitions (not only memory studies, as applied here). We have added substantial text to the Introduction distinguishing cRSA, which is widely employed, often in cases with a single repetition per stimulus, and model comparative methods that employ multiple repetitions. We clarify that we do not consider tRSA an alternative to the model comparative approach, and discuss that operational definitions of representational strength are constrained by the study design.

Page 3. “In this paper, we present an advancement termed trial-level RSA, or tRSA, which addresses these limitations in cRSA (not model comparison approaches) and may be utilized in paradigms with or without repeated stimuli”.

Page 4. “Representational geometry usually refers to the structure of similarities among repeated presentations of the same stimulus in the neural data (as captured in the brain RSM) and is often estimated utilizing a model comparison approach, whereas representational strength is a derived measure that quantifies how strongly this geometry aligns with a hypothesized model RSM. In other words, geometry characterizes the pattern space itself, while representational strength reflects the degree of correspondence between that space and the theoretical model under test”.

Finally, we clarified that in our simulation methods we assume a true underlying activity pattern and a random error pattern. The model RSM is computed based on the true pattern, whereas the brain RSM comes from the noisy pattern, not the model RSM itself.

Page 9. “Then, we generated two sets of noise patterns, which were controlled by parameters σ<sub>A</sub> and σ<sub>B</sub> , respectively, one for each condition”.

(4) The notation in the paper is often conflicting and should be clarified. The actual true and measured activity patterns should receive a unique notation that is distinct from the variances of these patterns across voxels. I assume that $\sigma_ijk$ is the noise variances (not standard deviation)? Normally, variances are denoted with $\sigma^2$. Also, if these are variances, they cannot come from a normal distribution as indicated on page 10. Finally, multi-level models are usually defined at the level of means (i.e., patterns) rather than at the level of variances (as they seem to be done here).

We have added notations for true and measured activity patterns to differentiate it from our notation for variance. We agree that multilevel models are usually defined at the level of means rather than at the level of variances and we include a Figure (Fig 1D) that describes the model in terms of the means. We clarify that the σ ($\sigma$) used in the manuscript were not variances/standard deviations themselves; rather, they were meant to denote components of the actual (multilevel) variance parameter. Each component was sampled from normal distributions, and they collectively summed up to comprise the final variance parameter for each trial. We have modified our notation for each component to the lowercase letter s to minimize confusion. We have also made our R code publicly available on our lab github, which should provide more clarity on the exact simulation process.

(5) In the first set of simulations, the authors sampled both model and brain RSM by drawing each cell (similarity) of the matrix from an independent bivariate normal distribution. As the authors note themselves, this way of producing RSMs violates the constraint that correlation matrices need to be positive semi-definite. Likely more seriously, it also ignores the fact that the different elements of the upper triangular part of a correlation matrix are not independent from each other (Diedrichsen et al. 2021). Therefore, it is not clear that this simulation is close enough to reality to provide any valuable insight and should be removed from the paper, along with the extensive discussion about why this simulation setting is plainly wrong (page 21). This would shorten and clarify the paper.

We have added justification of the mixed-effects model given the potential assumption violations. We caution readers to investigate the robustness of their models, and to employ permutation testing that does not make independence assumptions. We have also added checks of the model residuals and an example of permutation testing in the Appendix. Finally, we agree that the first simulation setting does not possess several properties of realistic RDMs/RSMs; however, we believe that there is utility in understanding the mathematical properties of correlations – an essential component of RSA – in a straightforward simulation where the ground truth is known, thus moving the simulation to Appendix 1.

(6) If I understand the second simulation setting correctly, the true pattern for each stimulus was generated as an NxP matrix of i.i.d. standard normal variables. Thus, there is no condition-specific pattern at all, only condition-specific noise/signal variances. It is not clear how the tRSA would be biased if there were a condition-specific pattern (which, in reality, there usually is). Because of the i.i.d. assumption of the true signal, the correlations between all stimulus pairs within conditions are close to zero (and only differ from it by the fact that you are using a finite number of voxels). If you added a condition-specific pattern, the across-condition RSA would lead to much higher "representational strength" estimates than a within-condition RSA, with obvious problems and biases.

The Reviewer is correct that the voxel values in the true pattern are drawn from i.i.d. standard normal distributions. We take the Reviewer’s suggestion of “condition-specific pattern” to mean that there could be a condition-voxel interaction in two non-mutually exclusive ways. The first is additive, essentially some common underlying multi-voxel pattern like [6, 34, -52, …, 8] for all condition A trials, and different one such pattern for condition B trials, etc. The second is multiplicative, essentially a vector of scaling factors [x1.5, x0.5, x0.8, …, x2.7] for all condition A trials, and a different one such vector for condition B trials, etc. Both possibilities could indeed affect tRSA as much as it would cRSA.

Importantly, If such a strong condition-specific pattern is expected, one can build a condition-specific model RDM using one-shot coding of conditions (see example figure; src: https://www.newbi4fmri.com/tutorial-9-mvpa-rsa), to either capture this interesting phenomenon or to remove this out as a confounding factor. This practice has been applied in multiple regression cRSA approaches (e.g., Cichy et al., 2013) and can also be applied to tRSA.

(7) The trial-level brain RDM to model Spearman correlations was analyzed using a mixed effects model. However, given the symmetry of the RDM, the correlations coming from different rows of the matrix are not independent, which is an assumption of the mixed effect model. This does not seem to induce an increase in Type I errors in the conditions studied, but there is no clear justification for this procedure, which needs to be justified.

We appreciate this important warning, and now caution readers to investigate the robustness of their models, and consider employing permutation testing that does not make independence assumptions. We have also added checks of the model residuals and an example of permutation testing in the supplement.

Page 46. “While linear mixed-effects modeling offers a powerful framework for analyzing representational similarity data, it is critical that researchers carefully construct and validate their models. The multilevel structure of RSA data introduces potential dependencies across subjects, stimuli, and trials, which can violate assumptions of independence if not properly modeled. In the present study, we used a model that included random intercepts for both subjects and stimuli, which accounts for variance at these levels and improves the generalizability of fixed-effect estimates. Still, there is a potential for systematic dependence across trials within a subject. To ensure that the model assumptions were satisfied, we conducted a series of diagnostic checks on an exemplar ROI (right LOC; middle occipital gyrus) in the Object Perception dataset, including visual inspection of residual distributions and autocorrelation (Appendix 3, Figure 13). These diagnostics supported the assumptions of normality, homoscedasticity, and conditional independence of residuals. In addition, we conducted permutation-based inference, similar to prior improvements to cRSA (Niliet al. 2014), using a nested model comparison to test whether the mean similarity in this ROI was significantly greater than zero. The observed likelihood ratio test statistic fell in the extreme tail of the null distribution (Appendix 3, Figure 14), providing strong nonparametric evidence for the reliability of the observed effect. We emphasize that this type of model checking and permutation testing is not merely confirmatory but can help validate key assumptions in RSA modeling, especially when applying mixed-effects models to neural similarity data. Researchers are encouraged to adopt similar procedures to ensure the robustness and interpretability of their findings”.

Exemplar Permutation Testing

To test whether the mean representational strength in the ROI right LOC (middle occipital gyrus) was significantly greater than zero, we used a permutation-based likelihood ratio test implemented via the permlmer function. This test compares two nested linear mixed-effects models fit using the lmer function from the lme4 package, both including random intercepts for Participant and Stimulus ID to account for between-subject and between-item variability.

The null model excluded a fixed intercept term, effectively constraining the mean similarity to zero after accounting for random effects:

ROI ~ 0 + (1 | Participant) + (1 | Stimulus)

The full model included the same random effects structure but allowed the intercept to be freely estimated:

ROI ~ 1 + (1 | Participant) + (1 | Stimulus)

By comparing the fit of these two models, we directly tested whether the average similarity in this ROI was significantly different from zero. Permutation testing (1,000 permutations) was used to generate a nonparametric p-value, providing inference without relying on normality assumptions. The full model, which estimated a nonzero mean similarity in the right LOC (middle occipital gyrus), showed a significantly better fit to the data than the null model that fixed the mean at zero (χ²(1) = 17.60, p = 2.72 × 10⁻⁵). The permutation-based p-value obtained from permlmer confirmed this effect as statistically significant (p = 0.0099), indicating that the mean similarity in this ROI was reliably greater than zero. These results support the conclusion that the right LOC contains representational structure consistent with the HMAXc2 RSM. A density plot of the permuted likelihood ratio tests is plotted along with the observed likelihood ratio test in Appendix 3 Figure 14.

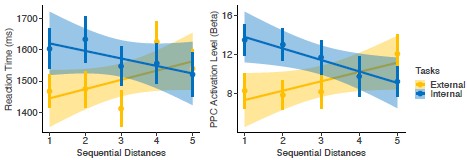

(8) For the empirical data, it is not clear to me to what degree the "representational strength" of cRSA and tRSA is actually comparable. In cRSA, the Spearman correlation assesses whether the distances in the data RSM are ranked in the same order as in the model. For tRSA, the comparison is made for every row of the RSM, which introduces a larger degree of flexibility (possibly explaining the higher correlations in the first simulation). Thus, could the gains presented in Figure 7D not simply arise from the fact that you are testing different questions? A clearer theoretical analysis of the difference between the average row-wise Spearman correlation and the matrix-wise Spearman correlation is urgently needed. The behavior will likely vary with the structure of the true model RDM/RSM.

We agree that the comparability between mean row-wise Spearman correlations and the matrix-wise Spearman correlation is needed. We believe that the simulations are the best approach for this comparison, since they are much more robust than the empirical dataset and have the advantage of knowing the true pattern/noise levels. We expand on our comparison of mean tRSA values and matrix-wise Spearman correlations on page 42.

Page 42. “Although tRSA and cRSA both aim to quantify representational strength, they differ in how they operationalize this concept. cRSA summarizes the correspondence between RSMs as a single measure, such as the matrix-wise Spearman correlation. In contrast, tRSA computes such correspondence for each trial, enabling estimates at the level of individual observations. This flexibility allows trial-level variability to be modeled directly, but also introduces subtle differences in what is being measured. Nonetheless, our simulations showed that, although numerical differences occasionally emerged—particularly when comparing between-condition tRSA estimates to within-condition cRSA estimates—the magnitude of divergence was small and did not affect the outcome of downstream statistical tests”.

(9) For the real data, there are a number of additional sources of bias that need to be considered for the analysis. What if there are not only condition-specific differences in noise variance, but also a condition-specific pattern? Given that the stimuli were measured in 3 different imaging runs, you cannot assume that all measurement noise is i.i.d. - stimuli from the same run will likely have a higher correlation with each other.

We recognize the potential of condition-specific patterns and chose to constrain the analyses to those most comparable with cRSA. However, depending on their hypotheses, researchers may consider testing condition RSMs and utilizing a model comparison approach or employ the z-scored approach, as employed in the simulations above. Regarding the potential run confounds, this is always the case in RSA and why we exclude within-run comparisons. We have also added to the Discussion the suggestion to include run as a covariate in their mixed-effects models. However, we do not employ this covariate here as we preferred the most parsimonious model to compare with cRSA.

Page 46 - 47. “Further, while analyses here were largely employed to be comparable with cRSA, researchers should consider taking advantage of the flexibility of the mixed-effects models and include co variates of non-interest (run, trial order etc.)”.

(10) The discussion should be rewritten in light of the fact that the setting considered here is very different from the model-comparative RSA in which one usually has multiple measurements per stimulus per subject. In this setting, existing approaches such as RSA or PCM do indeed allow for the full modelling of differences in the "representational strength" - i.e., pattern variance across subjects, conditions, and stimuli.

We agree that studies advancing designs with multiple repetitions of a given stimulus image are useful in estimating the reliability of concept representations. We would argue however that model comparison in RSA is not restricted to such data. Many extant studies do not in fact have multiple repetitions per stimulus per subject (Wang et al., 2018 https://doi.org/10.1088/1741-2552/abecc3, Gao et al, 2022 https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhac058, Li et al, 2022 https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.26195, Staples & Graves, 2020 https://doi.org/10.1162/nol_a_00018) that allow for that type of model-comparative approach. While beneficial in terms of noise estimation, having multiple presentations was not a requirement for implementing cRSA (Kriegeskorte, 2008 https://doi.org/10.3389/neuro.06.004.2008). The aim of this manuscript is to introduce the tRSA approach to the broad community of researchers whose research questions and datasets could vary vastly, including but not limited to the number of repeated presentations and the balance of trial counts across conditions.

(11) Cross-validated distances provide a powerful tool to control for differences in measurement noise variances and possible covariances in measurement noise across trials, which has many distinct advantages and is conceptually very different from the approach taken here.

We have added language on the value of cross-validation approaches to RSA in the Discussion:

Page 47. “Additionally, we note that while our proposed tRSA framework provides a flexible and statistically principled approach for modeling trial-level representational strength, we acknowledge that there are alternative methods for addressing trial-level variability in RSA. In particular, the use of cross-validated distance metrics (e.g., crossnobis distance) has become increasingly popular for controlling differences in measurement noise variance and accounting for possible covariance structures across trials (Walther et al., 2016). These metrics offer several advantages, including unbiased estimation of representational dissimilarities under Gaussian noise assumptions and improved generalization to unseen data. However, cross-validated distances are conceptually distinct from the approach taken here: whereas cross-validation aims to correct for noise-related biases in representational dissimilarity matrices, our trial-level RSA method focuses on estimating and modeling the variability in representation strength across individual trials using mixed-effects modeling. Rather than proposing a replacement for cross-validated RSA, tRSA adds a complementary tool to the methodological toolkit—one that supports hypothesis-driven inference about condition effects and trial-level covariates, while leveraging the full structure of the data”.

(12) One of the main limitations of tRSA is the assumption that the model RDM is actually the true brain RDM, which may not be the case. Thus, in theory, there could be a different model RDM, in which representational strength measures would be very different. These differences should be explained more fully, hopefully leading to a more accessible paper.

Indeed, the chosen model RSM may not be the true RSM, but as the noise level increases the correlation between RSMs practically becomes zero. In our simulations we assume this to be true as a straightforward way to manipulate the correspondence between the brain data and the model. However, just like cRSA, tRSA is constrained by the model selections the researchers employ. We encourage researchers to have carefully considered theoretically-motivated models and, if their research questions require, consider multiple and potentially competing models. Furthermore, the trial-wise estimates produced by tRSA encourage testing competing models within the multiple regression framework. We have added this language to the Discussion.

Page 46. ..”choose their model RSMs carefully. In our simulations, we designed our model RSM to be the “true” RSM for demonstration purposes. However, researchers should consider if their models and model alternatives”.

Pages 45-46. “While a number of studies have addressed the validity of measuring representational geometry using designs with multiple repetitions, a conceptual benefit of the tRSA approach is the reliance on a regression framework that engenders the testing of competing conceptual models of stimulus representation (e.g., taxonomic vs. encyclopedic semantic features, as in Davis et al., 2021)”.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

(1) While I generally welcome the contribution, I take some issue with the accusatory tone of the manuscript in the Introduction. The text there (using words such as 'ignored variances', 'errouneous inferences', 'one must', 'not well-suited', 'misleading') appears aimed at turning cRSA in a 'straw man' with many limitations that other researchers have not recognized but that the new proposed method supposedly resolves. This can be written in a more nuanced, constructive manner without accusing the numerous users of this popular method of ignorance.

We apologize for the unintended accusatory tone. We have clarified the many robust approaches to RSA and have made our Introduction and Discussion more nuanced throughout (see also 3, 11 and16).

(2) The described limitations are also not entirely correct, in my view: for example, statistical inference in cRSA is not always done using classic parametric statistics such as t-tests (cf Figure 1): the rsatoolbox paper by Nili et al. (2014) outlines non-parametric alternatives based on permutation tests, bootstrapping and sign tests, which are commonly used in the field. Nor has RSA ever been conducted at the row/column level (here referred to by the authors as 'trial level'; cf King et al., 2018).

We agree there are numerous methods that go beyond cRSA addressing these limitations and have added discussion of them into our manuscript as well as an example analysis implementing permutation tests on tRSA data (see response to 7). We thank the reviewer for bringing King et al., 2014 and their temporal generalization method to our attention, we added reference to acknowledge their decoding-based temporal generalization approach.

Page 8. “It is also important to note that some prior work has examined similarly fine-grained representations in time-resolved neuroimaging data, such as the temporal generalization method introduced by King et al. (see King & Dehaene, 2014). Their approach trains classifiers at each time point and tests them across all others, resulting in a temporal generalization matrix that reflects decoding accuracy over time. While such matrices share some structural similarity with RSMs, they do not involve correlating trial-level pattern vectors with model RSMs nor do their second-level models include trial-wise, subject-wise, and item-wise variability simultaneously”.

(3) One of the advantages of cRSA is its simplicity. Adding linear mixed effects modeling to RSA introduces a host of additional 'analysis parameters' pertaining to the choice of the model setup (random effects, fixed effects, interactions, what error terms to use) - how should future users of tRSA navigate this?

We appreciate the opportunity to offer more specific proscriptions for those employing a tRSA technique, and have added them to the Discussion:

Page 46. “While linear mixed-effects modeling offers a powerful framework for analyzing representational similarity data, it is critical that researchers carefully construct and validate their models and choose their model RSMs carefully. In our simulations, we designed our model RSM to be the “true” RSM for demonstration purposes. However, researchers should consider if their models and model alternatives. However, researchers should always consider if their models match the goals of their analysis, including 1) constructing the random effects structure that will converge in their dataset and 2) testing their model fits against alternative structures (Meteyard & Davies, 2020; Park et al., 2020) and 3) considering which effects should be considered random or fixed depending on their research question”.

(4) Here, only a single real fMRI dataset is used with a quite complicated experimental design for the memory part; it's not clear if there is any benefit of using tRSA on a simpler real dataset. What's the benefit of tRSA in classic RSA datasets (e.g., Kriegeskorte et al., 2008), with fixed stimulus conditions and no behavior?

To clarify, our empirical approach uses two different tasks: an Object Perception task more akin to the classic RSA datasets employing passive viewing, and a Conceptual Retrieval task that more directly addresses the benefits of the trialwise approach. We felt that our Object Perception dataset is a simpler empirical fMRI dataset without explicit task conditions or a dichotomous behavioral outcome, whereas the Retrieval dataset is more involved (though old/new recognition is the most common form of memory retrieval testing) and dependent on behavioral outcomes. However, we recognize the utility of replication from other research groups and do invite researchers to utilize tRSA on their datasets.

(5) The cells of an RDM/RSM reflect pairwise comparisons between response patterns (typically a brain but can be any system; cf Sucholutsky et al., 2023). Because the response patterns are repeatedly compared, the cells of this matrix are not independent of one another. Does this raise issues with the validity of the linear mixed effects model? Does it assume the observations are linearly independent?

We recognize the potential danger for not meeting model assumptions. Though our simulation results and model checks suggest this is not a fatal flaw in the model design, we caution readers to investigate the robustness of their models, and consider employing permutation testing that does not make independence assumptions. We have also added checks of the model residuals and an example of permutation testing in the Appendix. See response to R1.

(6) The manuscript assumes the reader is familiar with technical statistical terms such as Type I/II error, sensitivity, specificity, homoscedasticity assumptions, as well as linear mixed models (fixed effects, random effects, etc). I am concerned that this jargon makes the paper difficult to understand for a broad readership or even researchers currently using cRSA that might be interested in trying tRSA.

We agree this jargon may cause the paper to be difficult to understand. We have expanded/added definitions to these terms throughout the methods and results sections.

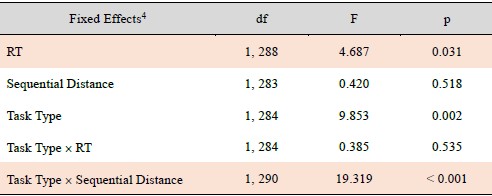

Page 12. “Given data generated with 𝑠<sub>𝑐𝑜𝑛𝑑,𝐴</sub> = 𝑠<sub>𝑐𝑜𝑛𝑑,B</sub>, the correct inference should be a failure to reject the null hypothesis of ; any significant () result in either direction was considered a false positive (spurious effect, or Type I error). Given data generated with , the inference was considered correct if it rejected the null hypothesis of and yielded the expected sign of the estimated contrast (b<sub>B-𝐴</sub><0). A significant result with the reverse sign of the estimated contrast (b<sub>B-𝐴</sub><0) was considered a Type I error, and a nonsignificant (𝑝 ≥ 0.05) result was considered a false negative (failure to detect a true effect, or Type II error)”.

Page 2. “Compared to cRSA, the multi-level framework of tRSA was both more theoretically appropriate and significantly sensitive (better able to detect) to true effects”.

Page 25.”The performance of cRSA and tRSA were quantified with their specificity (better avoids false positives, 1 - Type I error rate) and sensitivity (better avoids false negatives 1 - Type II error rate)”.

Page 6. “One of the fundamental assumptions of general linear models (step 4 of cRSA; see Figure 1D) is homoscedasticity or homogeneity of variance — that is, all residuals should have equal variance” .

Page11. “Specifically, a linear mixed-effects model with a fixed effect of condition (which estimates the average effect across the entire sample, capturing the overall effect of interest) and random effects of both subjects and stimuli (which model variation in responses due to differences between individual subjects and items, allowing generalization beyond the sample) were fitted to tRSA estimates via the `lme4 1.1-35.3` package in R (Bates et al., 2015), and p-values were estimated using Satterthwaites’s method via the `lmerTest 3.1-3` package (Kuznetsova et al., 2017)”.

(7) I could not find any statement on data availability or code availability. Given that the manuscript reuses prior data and proposes a new method, making data and code/tutorials openly available would greatly enhance the potential impact and utility for the community.

We thank the reviewer for raising our oversight here. We have added our code and data availability statements.

Page 9. “Data is available upon request to the corresponding author and our simulations and example tRSA code is available at https://github.com/electricdinolab”.

Reviewer #1 (Recommendations for the authors):

(13) Page 4: The limitations of cRSA seem to be based on the assumption that within each different experimental condition, there are different stimuli, which get combined into the condition. The framework of RSA, however, does not dictate whether you calculate a condition x condition RDM or a larger and more complete stimulus x stimulus RDM. Indeed, in practice we often do the latter? Or are you assuming that each stimulus is only shown once overall? It would be useful at this point to spell out these implicit assumptions.

We agree that stimulus x stimulus RDMs can be constructed and are often used. However, as we mentioned in the Introduction, researchers are often interested in the difference between two (or more) conditions, such as “remembered” vs. “forgotten” (Davis et al., https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhaa269) or “high cognitive load” vs. “low cognitive load” (Beynel et al., https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0531-20.2020). In those cases, the most common practice with cRSA is to construct condition-specific RDMs, compute cRSA scores separately for each condition, and then compare the scores at the group level. The number of times each stimulus gets presented does not prevent one from creating a model RDM that has the same rows and columns as the brain RDM, either in the same condition (“high load”) or across different conditions.

(14) Page 5: The difference between condition-level and stimulus-level is not clear. Indeed, this definition seems to be a function of the exact experimental design and is certainly up for interpretation. For example, if I conduct a study looking at the activity patterns for 4 different hand actions, each repeated multiple times, are these actions considered stimuli or conditions?

We have added clarifying language about what is considered stimuli vs conditions. Indeed, this will depend on the specific research questions being employed and will affect how researchers construct their models. In this specific example, one would most likely consider each different hand action a condition, treating them as fixed effects rather than random effects, given their very limited number and the lack of need to generalize findings to the broader “hand actions” category.

Page 5. “Critically, the distinction between condition-level and stimulus level is not always clear as researchers may manipulate stimulus-level features themselves. In these cases, what researchers ultimately consider condition-level and stimulus-level will depend on their specific research questions. For example, researchers intending to study generalized object representation may consider object category a stimulus-level feature, while researchers interested in if/how object representation varies by category may consider the same category variable condition-level”.

(15) Page 5: The fact that different numbers of trials / different levels of measurement noise / noise-covariance of different conditions biases non-cross-validated distances is well known and repeatedly expressed in the literature. We have shown that cross-validation of distances effectively removes such biases - of course, it does not remove the increased estimation variability of these distances (for a formal analysis of estimation noise on condition patterns and variance of the cross-nobis estimator, see (Diedrichsen et al. 2021)).

We thank the reviewer for drawing our attention to this literature and have added discussions of these methods.

(16). Page 5: "Most studies present subjects with a fixed set of stimuli, which are supposedly samples representative of some broader category". This may be the case for a certain type of RSA experiments in the visual domain, but it would be unfair to say that this is a feature of RSA studies in general. In most studies I have been involved in, we use a "stimulus" x "stimulus" RDM.

We have edited this sentence to avoid the “most” characterization. We also added substantial text to the introduction and discussion distinguishing cRSA, which is nonetheless widely employed, especially in cases with a single repetition per stimulus (Macklin et al., 2023, Liu et al, 2024) and the model comparative method and explicitly stating that we do not consider tRSA an alternative to the model comparative approach.

(17). Page 5: I agree that "stimuli" should ideally be considered a random effect if "stimuli" can be thought of as sampled from a larger population and one wants to make inferences about that larger population. Sometimes stimuli/conditions are more appropriately considered a fixed effect (for example, when studying the response to stimulation of the 5 fingers of the right hand). Techniques to consider stimuli/conditions as a random effect have been published by the group of Niko Kriegeskorte (Schütt et al. 2023).

Indeed, in some cases what may be thought of as “stimuli” would be more appropriately entered into the model as a fixed effect; such questions are increasingly relevant given the focus on item-wise stimulus properties (Bainbridge et al., Westfall & Yarkoni). We have added text on this issue to the Discussion and caution researchers to employ models that most directly answer their research questions.

Page 46. “However, researchers should always consider if their models match the goals of their analysis, including 1) constructing the random effects structure that will converge in their dataset and 2) testing their model fits against alternative structures (Meteyard & Davies, 2020; Park et al., 2020) and 3) considering which effects should be considered random or fixed depending on their research question. An effect is fixed when the levels represent the specific conditions of theoretical interest (e.g., task condition) and the goal is to estimate and interpret those differences directly. In contrast, an effect is random when the levels are sampled from a broader population (e.g., subjects) and the goal is to account for their variability while generalizing beyond the sample tested. Note that the same variable (e.g., stimuli) may be considered fixed or random depending on the research questions”.

(18) Page 6: It is correct that the "classical" RSA depends on a categorical assignment of different trials to different stimuli/conditions, such that a stimulus x stimulus RDM can be computed. However, both Pattern Component Modelling (PCM) and Encoding models are ideally set up to deal with variables that vary continuously on a trial-by-trial or moment-by-moment basis. tRSA should be compared to these approaches, or - as it should be clarified - that the problem setting is actually quite a different one.

We agree that PCM and encoding models offer a flexible approach and handle continuous trial-by-trial variables. We have clarified the problem setting in cRSA is distinct on page 6, and we have added the robustness of encoding models and their limitations to the Discussion.

Page 6. “While other approaches such as Pattern Component Modeling (PCM) (Diedrichsen et al., 2018) and encoding models (Naselaris et al., 2011) are well-suited to analyzing variables that vary continuously on a trial-by-trial or moment-by-moment basis, these frameworks address different inferential goals. Specifically, PCM and encoding models focus on estimating variance components or predicting activation from features, while cRSA is designed to evaluate representational geometry. Thus, cRSA as well as our proposed approach address a problem setting distinct from PCM and encoding models”.

(19) Page 8: "Then, we generated two noise patterns, which were controlled by parameters 𝜎 𝐴 and 𝜎𝐵, respectively, one for each condition." This makes little sense to me. The noise patterns should be unique to each trial - you should generate n_a + n_b noise patterns, no?

We clarify that the “noise patterns” here are n_voxel x n_trial in size; in other words, all trial-level noise patterns are generated together and each trial has their own unique noise pattern. We have revised our description as “two sets of noise patterns” for clarity starting on page 9.

(20) Page 9: First, I assume if this is supposed to be a hierarchical level model, the "noise parameters" here correspond to variances? Or do these \sigma values mean to signify standard deviations? The latter would make little sense. Or is it the noise pattern itself?

As clarified in 4., the σ values are meant to denote hierarchical components of the composite standard deviation; we have updated our notation to use lower case letter s instead for clarity.

(21) Page 10: your formula states "𝜎<sub>𝑠𝑢𝑏𝑗</sub>~ 𝙽(0, 0.5^2)". This conflicts with your previous mention that \sigmas are noise "levels" are they the noise patterns themselves now? Variances cannot be normally distributed, as they cannot be negative.

As clarified in 4., the σ values are meant to denote hierarchical components of the composite standard deviation; we have updated our notation to use lower case letter s instead for clarity.

(22) Page 13: What was the task of the subject in the Memory retrieval task? Old/new judgements relative to encoding of object perception?

We apologize for the lack of clarity about the Memory Retrieval task and have added that information and clarified that the old/new judgements were relative to a separate encoding phase, the brain data for which has been reported elsewhere.

Page 14. “Memory Retrieval took place one day after Memory Encoding and involved testing participants’ memory of the objects seen in the Encoding phase. Neural data during the Encoding phase has been reported elsewhere. In the main Memory Retrieval task, participants were presented with 144 labels of real-world objects, of which 114 were labels for previously seen objects and 30 were unrelated novel distractors. Participants performed old/new judgements, as well as their confidence in those judgements on a four-point scale (1 = Definitely New, 2 = Probably New, 3 = Probably Old, 4 = Definitely Old)”.

(23) Page 13: If "Memory Retrieval consisted of three scanning runs", then some of the stimulus x stimulus correlations for the RSM must have been calculated within a run and some between runs, correct? Given that all within-run estimates share a common baseline, they share some dependence. Was there a systematic difference between the within-run and the between-run correlations?

We have clarified in this portion of the methods that within run comparisons were excluded from our analyses. We also double-checked that the within-run exclusion was included in the description of the Neural RSMs.

Page 14. “Retrieval consisted of three scanning runs, each with 38 trials, lasting approximately 9 minutes and 12 seconds (within-run comparisons were later excluded from RSA analyses)”.

Page 18. “This was done by vectorizing the voxel-level activation values within each region and calculating their correlations using Pearson’s r, excluding all within-run comparisons.”

(24) Page 20: It is not clear why the mean estimate of "representational strength" (i.e., model-brain RSM correlations) is important at all. This comes back to Major point #2, namely that you are trying to solve a very different problem from model-comparative RSA.

We have clarified that our approach is not an alternative to model-comparative RSA, and that depending on the task constraints researchers may choose to compare models with tRSA or other approaches requiring stimulus repetition (see 3).

(25) Page 21: I believe the problems of simulating correlation matrices directly in the way that the authors in their first simulation did should be well known and should be moved to an appendix at best. Better yet, the authors could start with the correct simulation right away.

We agree the paper is more concise with these simulations being moved to the appendix and more briefly discussed. We have implemented these changes (Appendix 1). However, we are not certain that this problem is unknown, and have several anecdotes of researchers inquiring about this “alternative” approach in talks with colleagues, thus we do still discuss the issues with this method.

(26) Page 26: Is the "underlying continuous noise variable 𝜎𝑡𝑟𝑖𝑎𝑙 that was measured by 𝑣𝑚𝑒𝑎𝑠𝑢𝑟𝑒𝑑 " the variance of the noise pattern or the noise pattern itself? What does it mean it was "measured" - how?

𝜎𝑡𝑟𝑖𝑎𝑙 is a vector of standard deviations for different trials, and 𝜎𝑡𝑟𝑖𝑎𝑙 i would be used to generate the noise patterns for trial i. v_measured is a hypothetical measurement of trial-level variability, such as “memorability” or “heartbeat variability”. We have revised our description to clarify our methods.

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations for the authors):

(8) It would be helpful to provide more clarity earlier on in the manuscript on what is a 'trial': in my experience, a row or column of the RDM is usually referred to as 'stimulus condition', which is typically estimated on multiple trials (instances or repeats) of that stimulus condition (or exemplars from that stimulus class) being presented to the subject. Here, a 'trial' is both one measurement (i.e., single, individual presentation of a stimulus) and also an entry in the RDM, but is this the most typical scenario for cRSA? There is a section in the Discussion that discusses repetitions, but I would welcome more clarity on this from the get-go.

We have added discussion of stimulus repetition methods and datasets to the Introduction and clarified our use of the terms.

Page 8. “Critically, in single-presentation designs, a “trial” refers to one stimulus presentation, and corresponds to a row or column in the RSM. In studies with repeated stimuli, these rows are often called “conditions” and may reflect aggregated patterns across trials. tRSA is compatible with both cases: whether rows represent individual trials or averaged trials that create “conditions”, tRSA estimates are computed at the row level”.

(9) The quality of the results figures can be improved. For example, axes labels are hard to read in Figure 3A/B, panels 3C/D are hard to read in general. In Figure 7E, it's not possible to identify the 'dark red' brain regions in addition to the light red ones.

We thank the reviewer for raising these and have edited the figures to be more readable in the manner suggested.

(10) I would be interested to see a comparison between tRSA and cRSA in other fMRI (or other modality) datasets that have been extensively reported in the literature. These could be the original Kriegeskorte 96 stimulus monkey/fMRI datasets, commonly used open datasets in visual perception (e.g., THINGS, NSD), or the above-mentioned King et al. dataset, which has been analyzed in various papers.

We recognize the great utility of replication from other research groups and do invite researchers to utilize tRSA on their datasets.

(11) On P39, the authors suggest 'researchers can confidently replace their existing cRSA analysis with tRSA': Please discuss/comment on how researchers should navigate the choice of modeling parameters in tRSA's linear mixed effects setting.

We have added discussion of the mixed-effects parameters and the various and encourage researchers to follow best practices for their model selection.

Page 46. “However, researchers should always consider if their models match the goals of their analysis, including 1) constructing the random effects structure that will converge in their dataset and 2) testing their model fits against alternative structures (Meteyard & Davies, 2020; Park et al., 2020) and 3) considering which effects should be considered random or fixed depending on their research question”.

(12) The final part of the Results section, demonstrating the tRSA results for the continuous memorability factor in the real fMRI data, could benefit from some substantiation/elaboration. It wasn't clear to me, for example, to what extent the observed significant association between representational strength and item memorability in this dataset is to be 'believed'; the Discussion section (p38). Was there any evidence in the original paper for this association? Or do we just assume this is likely true in the brain, based on prior literature by e.g. Bainbridge et al (who probably did not use tRSA but rather classic methods)?

Indeed, memorability effects have been replicated in the literature, but not using the tRSA method. We have expanded our discussion to clarify the relationship of our findings and the relevant literature and methods it has employed.

Page 38. “Critically, memorability is a robust stimulus property that is consistent across participants and paradigms (Bainbridge, 2022). Moreover, object memorability effects have been replicated using a variety of methods aside from tRSA, including univariate analyses and representational analyses of neural activity patterns where trial-level neural activity pattern estimates are correlated directly with object memorability (Slayton et al, 2025).”

(13) The abstract could benefit from more nuance; I'm not sure if RSA can indeed be said to be 'the principal method', and whether it's about assessing 'quality' of representations (more commonly, the term 'geometry' or 'structure' is used).

We have edited the abstract to reflect the true nuisance in the current approaches.

Abstract. Neural representation refers to the brain activity that stands in for one’s cognitive experience, and in cognitive neuroscience, a prominent method of studying neural representations is representational similarity analysis (RSA). While there are several recent advances in RSA, the classic RSA (cRSA) approach examines the structure of representations across numerous items by assessing the correspondence between two representational similarity matrices (RSMs): usually one based on a theoretical model of stimulus similarity and the other based on similarity in measured neural data.

(14) RSA is also not necessarily about models vs. neural data; it can also be between two neural systems (e.g., monkey vs. human as in Kriegeskorte et al., 2008) or model systems (see Sucholutsky et al., 2023). This statement is also repeated in the Introduction paragraph 1 (later on, it is correctly stated that comparing brain vs. model is most likely the 'most common' approach).

We have added these examples in our introduction to RSA.

Page 3.”One of the central approaches for evaluating information represented in the brain is representational similarity analysis (RSA), an analytical approach that queries the representational geometry of the brain in terms of its alignment with the representational geometry of some cognitive model (Kriegeskorte et al., 2008; Kriegeskorte & Kievit, 2013), or, in some cases, compares the representational geometry of two neural systems (e.g., Kriegeskorte et al., 2008) or two model systems (Sucholutsky et al., 2023)”.

(15) 'theoretically appropriate' is an ambiguous statement, appropriate for what theory?

We apologize for the ambiguous wording, and have corrected the text:

Page 11. “Critically, tRSA estimates were submitted to a mixed-effects model which is statistically appropriate for modeling the hierarchical structure of the data, where observations are nested within both subjects and stimuli (Baayen et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2021)”.

(16) I found the statement that cRSA "cannot model representation at the level of individual trials" confusing, as it made me think, what prohibits one from creating an RDM based on single-trial responses? Later on, I understood that what the authors are trying to say here (I think) is that cRSA cannot weigh the contributions of individual rows/columns to the overall representational strength differently.

We thank the reviewer for their clarifying language and have added it to this section of the manuscript.

“Abstract. However, because cRSA cannot weigh the contributions of individual trials (RSM rows/columns), it is fundamentally limited in its ability to assess subject-, stimulus-, and trial-level variances that all influence representation”.

(17) Why use "RSM" instead of "RDM"? If the pairwise comparison metric is distance-based (e..g, 1-correlation as described by the authors), RDM is more appropriate.

We apologize for the error, and have clarified the Methods text:

Page3-4. First, brain activity responses to a series of N trials are compared against each other (typically using Pearson’s r) to form an N×N representational similarity matrix.

(18) Figure 2: please write 'Correlation estimate' in the y-axis label rather than 'Estimate'.

We have edited the label in Figure 2.

(19) Page 6 'leaving uncertain the directionality of any findings' - I do not follow this argument. Obviously one can generate an RDM or RSM from vector v or vector -v. How does that invalidate drawing conclusions where one e.g., partials out the (dis)similarity in e.g., pleasantness ratings out of another RDM/RSM of interest?

We agree such an approach does not invalidate the partial method; we have clarified what we mean by “directionality”.

Page 8. ”For instance, even though a univariate random variable , such as pleasantness ratings, can be conveniently converted to an RSM using pairwise distance metrics (Weaverdyck et al., 2020), the very same RSM would also be derived from the opposite random variable , leaving uncertain of the directionality (or if representation is strongest for pleasant or unpleasant items) of any findings with the RSM (see also Bainbridge & Rissman, 2018)”.

(20) P7 'sampled 19900 pairs of values from a bi-variate normal distribution', but the rows/columns in an RDM are not independent samples - shouldn't this be included in the simulation? I.e., shouldn't you simulate first the n=200 vectors, and then draw samples from those, as in the next analysis?

This section has been moved to Appendix 1 (see responses to Reviewer 1.13).

(21) Under data acquisition, please state explicitly that the paper is re-using data from prior experiments, rather than collecting data anew for validating tRSA.

We have clarified this in the data acquisition section.

Page 13. “A pre-existing dataset was analyzed to evaluate tRSA. Main study findings have been reported elsewhere (S. Huang, Bogdan, et al., 2024)”.

(22) Figure 4 could benefit from some more explanation in-text. It wasn't clear to me, for example, how to interpret the asterisks depicted in the right part of the figure.

We clarified the meaning of the asterisks in the main text in addition to the existent text in the figure caption.

Page 26. “see Figure 4, off-diagonal cells in blue; asterisks indicate where tRSA was statistically more sensitive then cRSA)”.

(23) Page 38 "the outcome of tRSA's improved characterization can be seen in multiple empirical outcomes:" it seems there is one mention of 'outcomes' too many here.

We have revised this sentence.

Page 41. “tRSA's improved characterization can be seen in multiple empirical outcomes”.

(24) Page 38 "model fits became the strongest" it's not clear what aspect of the reported results in the paragraph before this is referring to - the Appendix?

Yes, the model fits are in the Appendix, we have added this in text citation.

Moreover, model-fits became the strongest when the models also incorporated trial-level variables such as fMRI run and reaction time (Appendix 3, Table 6).

References

Diedrichsen, J., Berlot, E., Mur, M., Schütt, H. H., Shahbazi, M., & Kriegeskorte, N. (2021). Comparing representational geometries using whitened unbiased-distance-matrix similarity. Neurons, Behavior, Data and Theory, 5(3). https://arxiv.org/abs/2007.02789

Diedrichsen, J., & Kriegeskorte, N. (2017). Representational models: A common framework for understanding encoding, pattern-component, and representational-similarity analysis. PLoS Computational Biology, 13(4), e1005508.

Diedrichsen, J., Yokoi, A., & Arbuckle, S. A. (2018). Pattern component modeling: A flexible approach for understanding the representational structure of brain activity patterns. NeuroImage, 180, 119-133.

Naselaris, T., Kay, K. N., Nishimoto, S., & Gallant, J. L. (2011). Encoding and decoding in fMRI. NeuroImage, 56(2), 400-410.

Nili, H., Wingfield, C., Walther, A., Su, L., Marslen-Wilson, W., & Kriegeskorte, N. (2014). A toolbox for representational similarity analysis. PLoS Computational Biology, 10(4), e1003553.

Schütt, H. H., Kipnis, A. D., Diedrichsen, J., & Kriegeskorte, N. (2023). Statistical inference on representational geometries. ELife, 12. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.82566

Walther, A., Nili, H., Ejaz, N., Alink, A., Kriegeskorte, N., & Diedrichsen, J. (2016). Reliability of dissimilarity measures for multi-voxel pattern analysis. NeuroImage, 137, 188-200.

King, M. L., Groen, I. I., Steel, A., Kravitz, D. J., & Baker, C. I. (2019). Similarity judgments and cortical visual responses reflect different properties of object and scene categories in naturalistic images. NeuroImage, 197, 368-382.

Kriegeskorte, N., Mur, M., Ruff, D. A., Kiani, R., Bodurka, J., Esteky, H., ... & Bandettini, P. A. (2008). Matching categorical object representations in inferior temporal cortex of man and monkey. Neuron, 60(6), 1126-1141.

Nili, H., Wingfield, C., Walther, A., Su, L., Marslen-Wilson, W., & Kriegeskorte, N. (2014). A toolbox for representational similarity analysis. PLoS computational biology, 10(4), e1003553.

Sucholutsky, I., Muttenthaler, L., Weller, A., Peng, A., Bobu, A., Kim, B., ... & Griffiths, T. L. (2023). Getting aligned on representational alignment. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.13018.