FieldNote Sketch Summary

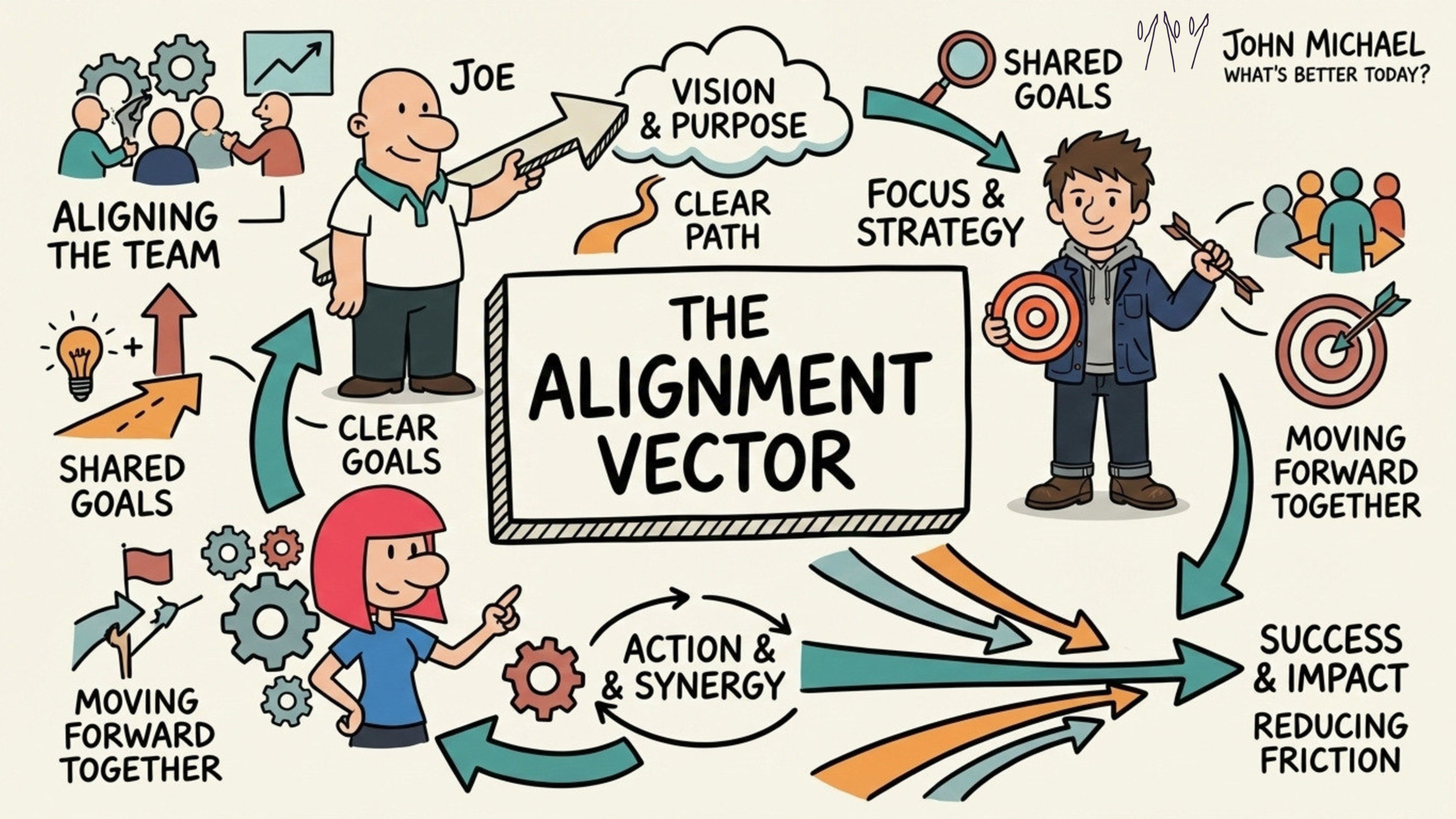

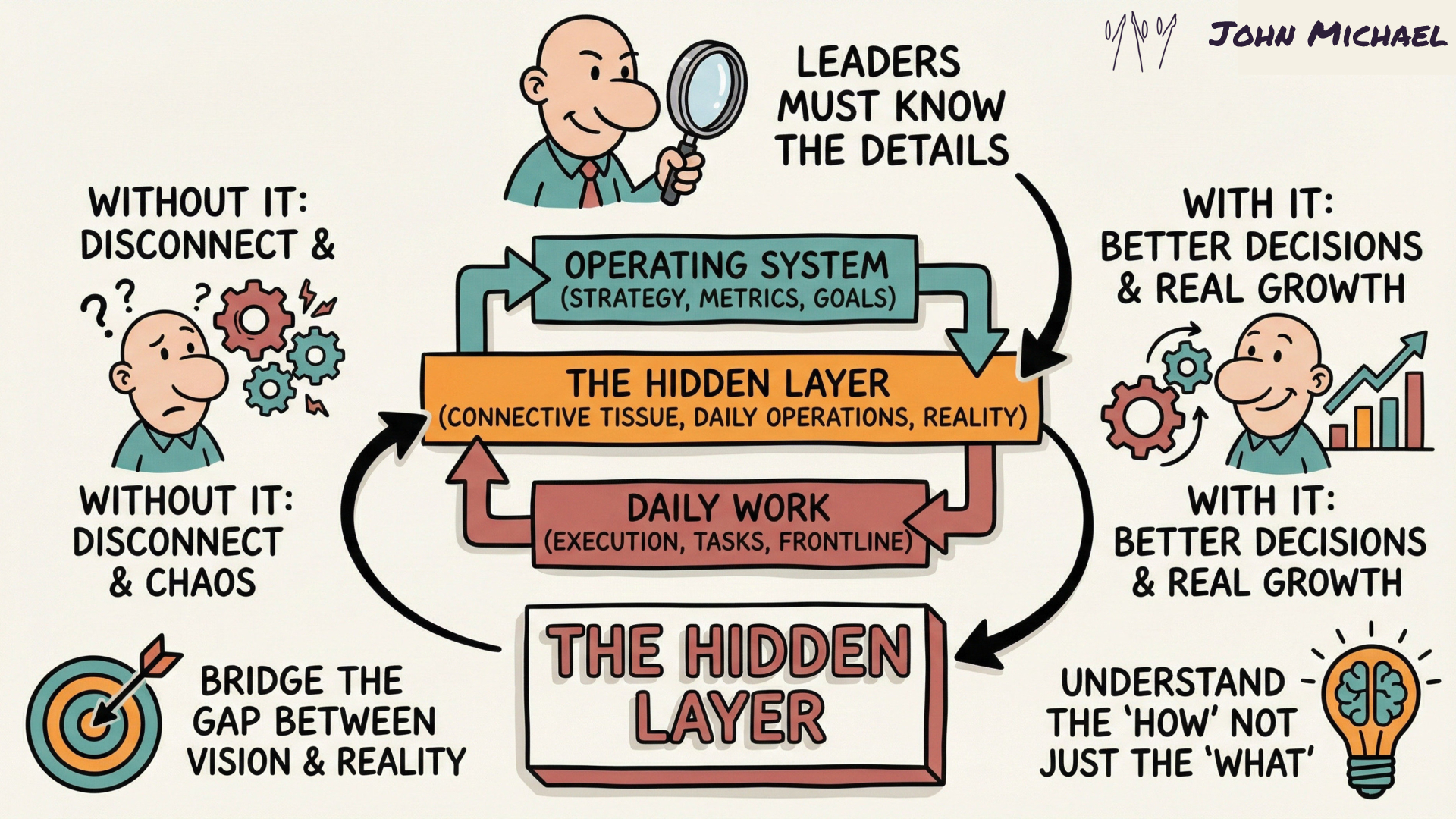

Save this SketchNote about Alignment for yourself or share it with someone you know needs to re-align themselves.

Save this SketchNote about Alignment for yourself or share it with someone you know needs to re-align themselves.

FieldNote Sketch Summary

Save this SketchNote about Alignment for yourself or share it with someone you know needs to re-align themselves.

Save this SketchNote about Alignment for yourself or share it with someone you know needs to re-align themselves.

Only a few studies have examined neural structure in relation tobirth weight across the normal range.

Limited data?

To paste a screenshot into Claude, use Ctrl+V (not Cmd+V on macOS). This keyboard shortcut is specifically designed for pasting screenshots into the chat interface.

在 claude code 粘贴截图

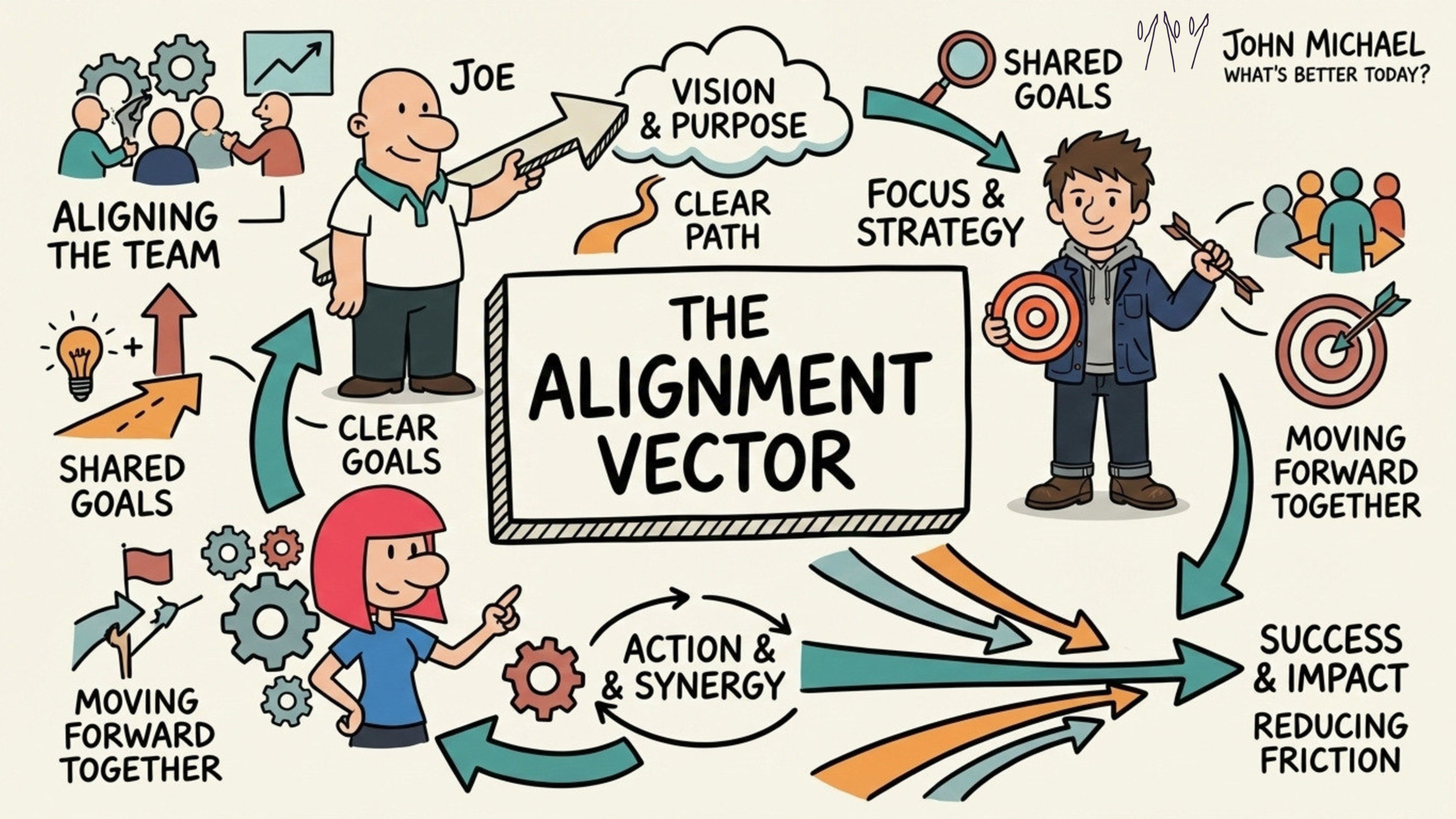

SketchNotes: Visual summaries of FieldNotes and FieldGuides - available in the 'Hidden' Layer. The Sketchnote for this Guide is here.

Get your SketchNote for your Orientation here:

Save a copy of this SketchNote for your reminder or share it with someone you care about.

Save a copy of this SketchNote for your reminder or share it with someone you care about.

p.s. Want the visual map? You'll find a full FieldNote Sketch Summary of this inside the 'hidden' layer. Click this highlight to see the synthesis, share it with someone you know needs it and save a copy for yourself.

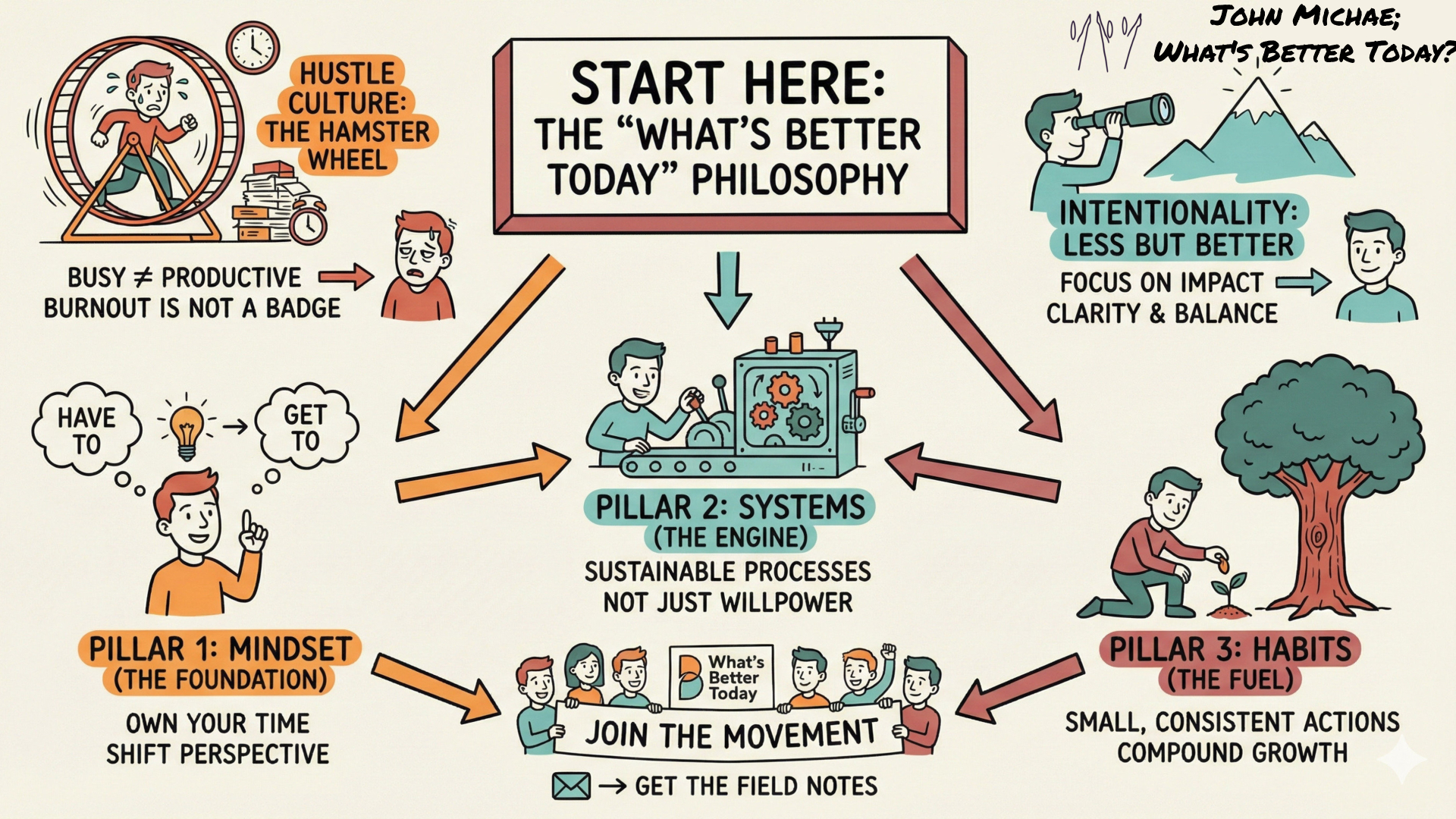

Save this Gateway SketchNote as a quick reminder for yourself or share it with someone you know needs to check this out.

Save this Gateway SketchNote as a quick reminder for yourself or share it with someone you know needs to check this out.

FieldNote Sketch Summary

Yes, you're in the "hidden" layer - not so hidden now huh?

Save this for yourself or share it with someone who needs to know that you are one who digs deeper and looks beyond the surface.

Yes, you're in the "hidden" layer - not so hidden now huh?

Save this for yourself or share it with someone who needs to know that you are one who digs deeper and looks beyond the surface.

It was a balmy night in Deerfield Beach, Florida. The conference was packed with philosophers, sociologists, and programmers, all intent on examining the latest developments in consciousness and artificial intelligence. Papers had been presented, models dissected, scenarios examined. I had brought my camera along, without any clear idea of what I meant to photograph. But seeing Sophia there sparked an idea. Portrait photography is usually about connecting with other human beings and trying to capture their essence, presenting whatever it is that makes them beautiful and unique. What if I were to photograph Sophia—a humanoid robot developed by Hanson Robotics—and then, in a separate session, the philosopher David Chalmers, a prominent theorist of consciousness, and reflect on the experience? What might I learn from those encounters that I had not already gleaned from the analytical papers and philosophical discussions?

will this be seen

To the IDW, trans people and their advocates are destroying the pillars of our society with such free-speech–suppressing, postmodern concepts as: “trans women are women,” “gender-neutral pronouns,” or “there are more than two genders.” Asserting “basic biology” will not be ignored, the IDW proclaims. “Facts don’t care about your feelings.”

This context is important to understand because it lays the groundwork for the audience on the opposing side of the argument. it clearly gives an example of why she feels the need to write this argument.

So, no matter what a pundit, politician or internet troll may say, trans people are an indispensable part of our living reality.

Sun seems to be motivated to write this text to argue against the highlighted. being that she is also transgender, arguing against false claims using the basis of science (her background), gives a greater purpose and to back her own safety, etc...

By Simón(e) D Sun

Dr. Simone D Sun (PHD) is a scientist, artist, and advocate in the J. Tollkuhn Lab at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, a Senior Fellow at the Center for Applied Transgender Studies, and a 2023 HHMI Hanna H. Gray Fellow. They received their PhD in the R.W. Tsien Lab at the NYU Neuroscience Institute studying neuroplasticity. This information is important becasue it males her argument in this text more credible. The publisher is SCI AM, a credible becasue of its long history of science publication.

Stop Using Phony Science to Justify Transphobia

This title seems to embody what the authors main message is. her reasonings are scientific, backed by sources with research, making her argument viable.

Let’s just take the most famous example of sexual dimorphism in the brain: the sexually dimorphic nucleus of the preoptic area (sdnPOA). This tiny brain area with a disproportionately sized name is slightly larger in males than in females. But it’s unclear if that size difference indicates distinctly wired sdnPOAs in males versus females, or if—as with the bipotential primordium—the same wiring is functionally weighted toward opposite ends of a spectrum. Throw in the observation that the sdnPOA in gay men is closer to that of straight females than straight males, and the idea of “the male brain” falls apart.

This small paragraph displays that the text is meant for college students and also individuals familiar with biology, and can understand scientific reasoning from research. We also know because most likely, those who are subscribing to the SCI AM are generally interested in or have a background in STEM/science

Contrary to popular belief, scientific research helps us better understand the unique and real transgender experience.

This quote sets the stage for the following text, and signals to the readers that she will be going in depth, and could use scientific terms throughout her argument.

It is time that we acknowledge this. Defining a person’s sex identity using decontextualized “facts” is unscientific and dehumanizing.

Sun seems to bring in her whole argument, and in one sentence puts what she wants her readers to tale away from the text, on the table.

Defining a person’s sex identity using decontextualized “facts” is unscientific and dehumanizing.

Actual research shows that sex is anything but binary

June 13, 2019

While brief and coordinated SRY-activation initiates the process of male-sex differentiation, genes like DMRT1 and FOXL2 maintain certain sexual characteristics during adulthood.

Nearly everyone in middle school biology learned that if you’ve got XX chromosomes, you’re a female; if you’ve got XY, you’re a male.

The popular belief that your sex arises only from your chromosomal makeup is wrong.The truth is, your biological sex isn’t carved in stone, but a living system with the potential for change.

reflects the views of the author

By Simón(e) D Sun

June 13, 2019

and reflects the views of the author

After the primordium forms, SRY—a gene on the Y chromosome discovered in 1990, thanks to the participation of intersex XX males and XY females—might be activated.*

The popular belief that your sex arises only from your chromosomal makeup is wrong.The truth is, your biological sex isn’t carved in stone, but a living system with the potential for change.

Nearly everyone in middle school biology learned that if you’ve got XX chromosomes, you’re a female; if you’ve got XY, you’re a male. T

Contrary to popular belief, scientific research helps us better understand the unique and real transgender experience. Specifically, through three subjects: (1) genetics, (2) neurobiology and (3) endocrinology. So, hold onto your parts, whatever they may be. It’s time for “the talk.”

Antiscientific sentiment bombards our politics, or so says the Intellectual Dark Web (IDW)

3.This first line shows the exigence of the article, or what motivated the author to write this article. It essentially stemmed from groups on the internet spreading hateful, false rhetoric in order to influence the opinions of their readers. The author of this article, however, recognized the potential dangers of this, and therefore, wrote this article.

It seems fitting to follow up the expectations for the first year with a list of common challenges that college students encounter along the way to a degree.

Annotation 2: Reading about imposter syndrome really stood out to me because it’s something a lot of students probably experience but don’t talk about. I have experienced it myself, especially going back to school after many years. Knowing that feeling unsure or overwhelmed is normal makes college feel less intimidating. It reminded me to be patient with myself while adjusting and to not give up when things get hard.

My father Capulet will have it so;

this shows that capulet is forcing the marrige

Come, stir, stir, stir!

this showes how capulet wants to control the weeding by giving orders.

hie, make haste, Make haste; the bridegroom he is come already: Make haste, I say.

its shows how excited capulet is for the weeding.

Public memory is produced from a political discussion that involvesnot so much specific economic or moral problems but rather funda-mental issues about the entire existence of a society: its organization,| structure of power, and the very meaning of its past and present.

The struggle with memory can be political because it is how we understand the power of politics in the past.

Lisbon is the culmination of a continuous process of constitutional change assimilating EU decision-making to domestic decision-making. On the other hand, as it enters ever more deeply into sovereignty-sensitive areas of the Member States, post-Lisbon co-decision is also potentially a vehicle of collision between the EU and the domestic political orders.

MAIN ARGUMENT / THESIS - Have explained how to measure these changes - Changes are cultural (I.e., rhetorically framing legislative power as such / democracy as opposd to regulation) and political (enlarged SCOPE of the co-decision process / EP and Council even if INSTITUTIONS THEMSELVES did not change) - Scope specifically includes SENSITIVE AREAS like criminal law / counter terrorism -> traditional domains of the state / nation - THEREFORE -> LISBON TREATY / OLP IS SIMULTANEOUSLY ACT THAT LEGITIMIZES EU CO-DECISION DEMOCRACY AND ALSO ONE THAT THREATENS FURTHER TENSION BETWEEN MEMBER STATES AND AND EU -> PRECISELY BECAUSE OF ENLARGENED SCOPE OF WHAT CAN BE LEGISLATED ON TO INCLDUE SENSITIVE, USUALLY JUST INTER-GOVERNMENTAL, AREAS LIKE CRIMINAL LAW.

"Lisbon is the culmination of a continuous process of constitutional change assimilating EU decision-making to domestic decision-making. On the other hand, as it enters ever more deeply into sovereignty-sensitive areas of the Member States, post-Lisbon co-decision is also potentially a vehicle of collision between the EU and the domestic political orders."

article has four parts. The first part examines how new the OLP is, considering that co-decision has, in one form or another, existed for some 25 years.

FOUR PARTS OF ARTICLE

Is the OLP new? What does it offer thats different, given that "co-decision" (i.e., cooperation between Council and Parliament, between national govts and supranational direct democracy) has ALREADY EXISTED FOR 25 YEARS

Main argument -> One can guage OLP's effect on the day-to-day lawmaking of Europe by looking at three areas:

The response of member states (their compliance w/ OLP rules)

Two empirical cases as evidence for contribution / impact of OLP

Regulation of financial markets (i.e., both are so different from one another that we can IDENTIFY OLP's impact by looking at how both are regulated SIMILARLY / via OLP policies)

Concluding assessment of democratic contribution of Lisbons' OLP (insights about aforementioned case studies)

This article investigates to what extent and how the Treaty of Lisbon has contributed to democratizing the EU polity, by focusing on the ordinary legislative procedure (OLP). In the system of multilevel democracy emerging from the Lisbon Treaty, the OLP epitomizes the idea that it is possible to have democratic law-making in a multilevel polity characterized by ‘overlapping political communities’ (Hurrelmann and Baglioni 2018) and a ‘persistent plurality of peoples’ (Nicolaidis 2004; see also Cheneval et al. 2015). This article takes stock of this idea by examining what role democratic aspirations played in the invention of the OLP, and how the OLP in practice has delivered on such aspirations.

"This article investigates to what extent and how the Treaty of Lisbon has contributed to democratizing the EU polity, by focusing on the ordinary legislative procedure (OLP). In the system of multilevel democracy emerging from the Lisbon Treaty, the OLP epitomizes the idea that it is possible to have democratic law-making in a multilevel polity characterized by ‘overlapping political communities’ (Hurrelmann and Baglioni 2018) and a ‘persistent plurality of peoples’ (Nicolaidis 2004; see also Cheneval et al. 2015). This article takes stock of this idea by examining what role democratic aspirations played in the invention of the OLP, and how the OLP in practice has delivered on such aspirations."

Basically, THESIS / AIM OF ARTICLE is extent to which Treaty of Lisbon CODIFIED / INTRODUCED DEMOCRACY INTO EU (of "democratizing the EU polity) -> Therefore making it a DEMOCRATIC New Political Order.

OLP in particular is evidence of idea that its possible to have DEMOCRATIC PROCESS INVOLVING MULTIPLE COUNTIRES WITH THEIR OWN LAWS -> This was the key concern before OLP / Lisbon / Maastrachit -> basically that it might be impossibe to have democratic law making / representation on a transnational scale.

Again, also looking at how democratic aspirations / persons with them played into this.

a political entity which had evolved institutions and procedures well beyond those of an international organization, but remained fundamentally messy.

IN OTHER WORDS -> looking at how this helped bring the EU out of an "international organization" and into some sort of actual democratic / legislative body -> elevates it from simply regulatory body to government - BEFORE Maastricht, scholars tried to find out what the new "POLITCAL ORDER" was now that the EC was more unified -> again, conclude that the nascent EU/EC is WAY MORE POWERFUL THAN ANYTHING ELSE on an international scale, but remains "messy." - Part of this mess was fact that there was no OVERARCHING POLICY OR GOAL -> simply "general principles or tendencies" - Again, many hope at this point (again, like 1990 before EU treaty of 1992) for greater transnational demoicratic institutions, not just (appointed?) regulatory body.

Acquiring knowledge involves active and constructive processing of new information. There are many ways to acquire new knowledge; however, learning strategies that actively engage students and promote student interactions lead to the strongest learning in STEM students (NRC, 2012; Freeman et al., 2014).

I think "Actively Engage Students" is the key! The more they can be engaged in solving a problem individually or in a group, the more they can learn. Sometimes even a short question with iClicker can lead to an active learning with a better results than just talking and teaching without involving students.

Connect means linking new knowledge with prior knowledge. Imagine a student’s existing knowledge as a set of interconnected nodes in a network. A connect activity intentionally activates some of the nodes (i.e., recalling knowledge) and suggests new connections among nodes or ways that nodes can be organized.

I totally agree with this and truly believe that I should try to put myself in students shoes and understand what they know from previous courses or topics, and how this new subject is relevant to those, so that they know why they learned those concepts and how they can use them now. It is kind of showing students how you learn from beginner to intermediate and then to advanced topics gradually.

They should be good servants and intelligent, for I observed that they quickly took in what was said to them, and I believe that they would easily be made Christians, as it appeared to me that they had no religion

This statement shows Columbus’s justification for colonization by portraying Indigenous people as fit for servitude and conversion, brushing aside their existing beliefs and autonomy.

They neither carry nor know anything of arms, for I showed them swords, and they took them by the blade and cut themselves through ignorance.

Columbus interprets unfamiliarity with European weapons as ignorance, showing Indigenous people as naive and reinforcing his perception of their vulnerability.

gave to some of them red caps, and glass beads to put round their necks, and many other things of little value, which gave them great pleasure, and made them so much our friends that it was a marvel to see.

This sentence reveals Columbus’s belief that Indigenous people could be easily won over with inexpensive objects, reflecting a Eurocentric assumption that material gifts could quickly secure loyalty and control.

yeataans soz aoueyp Afuo ayp quasardar pasput saop a8en8ury ‘ayeumorzre ap Joy ‘xayJaxdz03s ays 10,J “UaUT JayI0 puodaq "ynour jo pom Aq ‘paarams sey ay Jey) put ‘oyeUMorE ay} yim auto s} ay IeYB sn 03 sINDd20 IT ‘padfoauy ysq1 94) Jo pue ‘asenduey ut opty sty jo s[]a1 apy "y8noua sr 3ey puy “yseur sty pue aouasazd sry st daoys ayp ut yeya adaoxa ‘any noge apay 472A mouy af “patajqezun pue ssgjauueu st sajjaaA10as af],

Is is implied the storyteller and arrow maker are one and the same

aouayradxa Arexa -2] ano souIULaiap AtOIs sIY puL ‘TOYeUIMOIIe ayy saupUazep asendur] ‘ahay st siya avy2 aqnop ou aaey J ‘ued ay Aem ATU ay] UT IT sUOIZUOD ay ivya pure ‘oreipoumm pue yeai8 st ued sry 34a pueyssapun 03 uaais aie am pur ‘quoye pue somes st ay yey2 31 sey Azoas ap sed puy

The story is important of the phenomena and positionalities it conveys.

‘awn ur yjasa1 Jo axour pur azoww aai8 2 sttiaas YW Lueaz2 st aad pu ‘xapduzoa si ay ‘aanavIoNy JO UONIUOp v pur adurexe uv yroq stu

The dual roles it serves.

vad & pur uonsanb ¥ osye st yo1yM ‘uonvrepap ayduns srya uy pornguaa st Buryadiaacy

The power of multi-meaning-ladenness.

gouryeq ays ut apy] Azad sty saseyd ay Rtnop os ur pu ‘syvads ay Ieya st 3ez jedounad ayy, “shes ay igi poapur pur—sdes ay 2eyM UE Ing ‘saop JayxeUMoIe ay FyM GP YPMUT os WU SalT A108 aya jo amiod aL ‘pyod si yoryas yey pue Bury out uoaMioq aduasagpip our st azaya ‘Aqyenaa A, ‘palqns umo si Jo paored pur tid agoyadayy sta pure ‘ype qaqye ‘gBendury inoqe st If

Language's self-aware centrality to the story. While rupturing a distinction.

‘MONIUIXa Woy parouras uorerquad auo Inq waaq shee sey at ‘pyer uaag sey Aaoys aya se sau Aueur se Joy ‘os aq 09 saeadde px uONpEN aya asngaq snonues ‘uoppery yeto ap TIP aM YpIqAs adengury yo urey> quai IsoU JeYI UE UT] sNONUA? B “Mz E JO uorssassod awatid ayy usag sey Joyeumolie aya Jo Azoas ayp Apuazer Area IQ)

The cultural positioning of the story.

yaeoy s,Aaxaua ay) 02 ysre1s Has Mowe oy, ‘Bus ayy Jo o8 a] ay pue ‘pooas Auraua sity atayas ooujd aya uodn yay ware sry asey ay

The tale concluded in violence.

The Kiowas made fine arrows and straight- ened them in their teeth. Then they drew them to the bow to see that they were straight.

A culture and on of its practices.

t remains for me one of the most intensely vital stories in my experience, not only because it is a supernal example of the warrior idea—an adventure story in the best sense—but because it is a story about story, about the efficacy of language and the power of words. One does not come to the end of such a story.

Details the story's thematic contents, and the meanings it conveys.

he story of the arrowmaker, the “man made of words,” is perhaps the first story I was told.

Immediately brings up the personal temporal significance which the text's subject-matter has for the author.

The world’s richest 1% have used up their fair share of carbon emissions just 10 days into 2026, analysis has found.Meanwhile, the richest 0.1% took just three days to exhaust their annual carbon budget, according to the research by Oxfam.

how about a tax on their surplus use?

for every 1 mol of N2 we use 2mol of ammonia and the format represents this.

While AI excels in data processing and statistics, it lacks the ability to create truly innovative and creative solutions; machines calculate and they do not have human experiences

Искусственный интеллект не в силах создать что-то "новое, креативное" для решения наших проблем - лишь предложить один из существующих, имеющихся способов

We know that generative AI doesn’t understand the human context, so it’s not going to provide wisdom about social, emotional, and contextual events, because those are not part of its repertoire

ИИ не способен понять людей и решить человеческие проблемы из-за отсутствия понимания

A recent MIT Media Lab study reported that “excessive reliance on AI-driven solutions” may contribute” to “cognitive atrophy” and shrinking of critical thinking abilities. The study is small and is not peer-reviewed, and yet it delivers a warning that even artificial intelligence assistants are willing to acknowledge. When we asked ChatGPT whether AI can make us dumber or smarter, it answered, “It depends on how we engage with it: as a crutch or a tool for growth.”

Введение в тему статьи, отражает проблему слишком высокого доверия к ИИ

acknowledgement for the denigrating treatment students receive at work, or they are finally given space to reflect on the internalized effects of colorism on their self-esteem, or students may express cathartic anger that the racially segregated neighborhoods they grew up in have been designed with purpose and targeted for police surveillance and violence.

What ES is..

ll this decade, all over the world, countries have taken up arms against concentrated corporate power. We've had big, muscular antitrust attacks on big corporations in the US (under Trump I and Biden); in Canada; in the UK; in the EU and member states like Germany, France and Spain; in Australia; in Japan and South Korea and Singapore; in Brazil; and in China. This is a near-miraculous turn of affairs. All over the world, governments are declaring war on monopolies, the source of billionaires' wealth and powe

Trustbusting is a groundswell. Use it

I am hopeful. Not optimistic. Fuck optimism! Optimism is the idea that things will get better no matter what we do. I know that what we do matters. Hope is the belief that if we can improve things, even in small ways, we can ascend the gradient toward the world we want, and attain higher vantage points from which new courses of action, invisible to us here at our lower elevation, will be revealed. Hope is a discipline. It requires that you not give in to despair. So I'm here to tell you: don't despair.

hope, Vgl my talk #sotn18 where I said the same thing. It's an action

t's national security hawks who are worried about Trump bricking their ministries or their tractors, and who are also worried – with just cause – about Xi Jinping bricking all their solar inverters and batteries. Because, after all, the post-American internet is also a post-Chinese internet!

Natsec as driver, als post-Chinese

The fact that you have to figure out whether the discussion you're trying to join is on Twitter or Bluesky, Mastodon or Instagram – that is just the most Prodigy/AOL/Compuserve-ass way of running a digital world. I mean, 1990 called and they want their walled gardens back

current silos compared to AOL and Compuserve era. Good one

But most of all, enshittification is the result of anticircumvention law's ban on interoperability.

Core premise: enshittification is caused by anticircumvention bc you've nowhere to go. This is a deepening of his adversarial interoperability concept

Polish hackers from the security research firm Dragon Sector presented on their research into this disgusting racket in this very hall, and now, they're being sued by Newag under anticircumvention law, for making absolutely true disclosures about Newag's deliberately defective products

Newag is suing the Polish Dragon Sector company for anticircumvention in exposing this

that's the Polish train company Newag. Newag sabotages its own locomotives, booby-trapping them so that if they sense they have been taken to a rival's service yard, the train bricks itself. When the train operator calls Newag about this mysterious problem, the company "helpfully" remotes into the locomotive's computers, to perform "diagnostics," which is just sending a unbricking command to the vehicle, a service for which they charge 20,000 euros

ah, as expected

Congress just killed a military "right to repair" law. So now, US soldiers stationed abroad will have to continue the Pentagon's proud tradition of shipping materiel from generators to jeeps back to America to be fixed by their manufacturers

The US military 'just' lost their anticircumvention exemption.

btw, this doesn't happen just w US products, see trains in Poland. So there may be internal counterforces to this in the EU.

Then there's Medtronic, a company that pretends it is Irish. Medtronic is the world's largest med-tech company, having purchased all their competitors, and then undertaken the largest "tax-inversion" in history, selling themselves to a tiny Irish firm, in order to magick their profits into a state of untaxable grace, floating in the Irish Sea.

Medtronic did the same for ventilators.

From Mercedes, which rents you the accelerator pedal in your luxury car, only unlocking the full acceleration curve of your engine if you buy a monthly subscription; to BMW, which rents you the automated system that automatically dims your high-beams if there's oncoming traffic.

BMW and Mercedes have subscriptions on features in their cars

Anticircumvention law is the reason that Volkswagen could get away with Dieselgate.

Dieselgate would have happened sooner

But what if European firms want to go on taking advantage of anticircumvention laws? Well, there's good news there, too. "Good news," because the EU firms that rely on anticircumvention are engaged in the sleaziest, most disgusting frauds imaginable.

ah, right on time. On to EU firms counting on anticircumvention

It used to be that countries that depended on USAID had to worry about losing food, medical and cash supports if they pissed off America. But Trump killed USAID, so now that's a dead letter.

The erosion of all soft-power of the US is feeding into this

Besides, we don't need Europe to lead the charge on a post-American internet by repealing anticircumvention. Any country could do it! And the country that gets there first gets to reap the profits

It only takes a single state gov to do away with anticircumvention. Question is: aren't there already countries that don't have this clause? If so, why hasn't this happened yet then?

But crises precipitate change. Remember when another mad emperor – Vladimir Putin – invaded Ukraine, and Europe experienced a dire energy shortage? In three short years, the continent's solar uptake skyrocketed. The EU went from being 15 years behind in its energy transition, to ten years ahead of schedule.

True? Did we see acceleration in solar since early 2022, shortening the timeline with 10 yrs? What was the sched anyway?

the project of building a post-American internet: a project to reduce tech debt, to unlock America's monopoly trillions and divide them among the world's entrepreneurs (for whom they represent untold profits), and the world's technology users (for whom they represent untold savings); all while building resiliency and sovereignty.

post-American internet as a project reducing tech-debt (meaning in this context?)

When I was walking the picket line in Hollywood during the writer's strike, a writer told me that you prompt an AI the same way a studio boss gives shitty notes to a writer's room: "Make me ET, but make it about a dog, and give it a love interest, and a car-chase in the third act.

great quote

The thing is, software is not an asset, it's a liability. The capabilities that running software delivers – automation, production, analysis and administration – those are assets. But the software itself? That's a liability. Brittle, fragile, forever breaking down as the software upstream of it, downstream of it, and adjacent to it is updated or swapped out, revealing defects and deficiencies in systems that may have performed well for years.

software is a liability. Dutch equiv of this phrase? The assets are its impact : automation, production, analysis, admin

We wouldn't tolerate secrecy in the calculations used to keep our buildings upright, and we shouldn't tolerate opacity in the software that keeps our tractors, hearing aids, ventilators, pacemakers, trains, games consoles, phones, CCTVs, door locks, and government ministries working.

basically open standards, and open source as accountability

But there's one post-American system that's easy to imagine. The project to rip out all the cloud connected, backdoored, untrustworthy black boxes that power our institutions, our medical implants, our vehicles and our tractors; and replace it with collectively maintained, open, free, trustworthy, auditable code. This project is the only one that benefits from economies of scale, rather than being paralyzed by exponential crises of scale. That's because any open, free tool adopted by any public institution – like the Eurostack services – can be audited, localized, pen-tested, debugged and improved by institutions in every other country.

digital transition is possible because it scales through spreading. You don't have to solve exponential scale first.

also the national security hawks who are 100% justified in their extreme concern about their country's reliance on American platforms that have been shown to be totally unreliable.

posists it is the natsec angle that may kill anticircumvention, not the digital rights or econ angle

Step one of tearing down that wall is killing anticircumvention law, so that we can run virtual devices that can be scripted, break bootloaders to swap out firmware and generally seize the means of computation.

this requires removing anticircumvention

Any serious attempt at digital sovereignty needs migration tools that work without the cooperation of the Big Tech companies. Otherwise, this is like building housing for East Germans and locating it in West Berlin. It doesn't matter how great the housing is, your intended audience is going to really struggle to move in unless you tear down the wall.

Building alternatives only useful if you have a guaranteed path of migration. Bigtech will not provide it.

Just think of how Apple responded to the relatively minor demand to open up the iOS App Store, and now imagine the thermonuclear foot-dragging, tantrum-throwing and malicious compliance they'll come up with when faced with the departure of a plurality of the businesses and governments in a 27-nation bloc of 500,000,000 affluent consumers.

indeed.

We need scrapers and headless browsers to accomplish the adversarial interoperability that will guarantee ongoing connectivity to institutions that are still hosted on US cloud-based services, because US companies are not going to facilitate the mass exodus of international customers from their platform.

this is a good point. Bigtech will not stand by as customers move out. So you will likely must have circumvention tooling, ... which is illegal.

But Eurostack is heading for a crisis. It's great to build open, locally hosted, auditable, trustworthy services that replicate the useful features of Big Tech, but you also need to build the adversarial interoperability tools that allow for mass exporting of millions of documents, the sensitive data-structures and edit histories.

Applaudes Eurostack but signals problem: you need to build adversarial interoperability to export all that is locked in current silos, and that is illegal as it takes anticircumvention. Not sure if that is true at scale though

This is exactly the kind of infrastructural risk that we were warned of if we let Chinese companies like Huawei supply our critical telecoms equipment. Virtually every government ministry, every major corporation, every small business and every household in the world have locked themselves into a US-based, cloud-based service.

Warning of Chinese intrusion but not seeing the US one etc

he-said/Clippy-said between the justices of the ICC and the convicted monopolists of Microsoft, I know who I believe.

he-said/clippy-said , ha!

When the EU explained that this would not satisfy the regulation, Apple threatened to pull out of the EU. Then, once everyone had finished laughing, Apple filed more than a dozen bullshit objections to the order hoping to tie this up in court for a decade, the way Google and Meta did for the GDPR.

delaying tactics

When the EU hit Apple with an enforcement order under the Digital Markets Act, Apple responded by offering to allow third party app stores, but it would only allow those stores to sell apps that Apple had approved of.

delaying tactic by Apple

As Jeff Bezos said to the publishers: "Your margin is my opportunity." With these guys, it's always "disruption for thee, but not for me." When they do it to us, that's progress. When we do it to them, it's piracy, and every pirate wants to be an admiral. Well, screw that. Move fast and break Tim Cook's things. Move fast and break kings!

n:: move fast and break bigtech

The alternative was tariffs. Well, I don't know if you've heard, but we've got tariffs now!

US exported anticircumvention in their trade deals and won it to avoid tariffs. Doesn't say how that worked for the EU

every other country in the world has passed a law just like this in the years since. Here in the EU, it came in through Article 6 of the 2001 EU Copyright Directive.

art 6 of Copyright and Information Society Directive 2001/29

Note 2001/29 has been amended by Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market 2019/790, but I don't think in this aspect.

This is a law that Jay Freeman rightly calls "Felony Contempt of Business Model." Anticircumvention became the law of the land in 1998 when Bill Clinton signed the DMCA

felony contempt of business model, ha!

USA: Section 1201 of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998 establishes a felony punishable by a five year prison sentence and a $500,000 fine for a first offense for bypassing an "access control" for a copyrighted work.

USA DMCA 1998, section 1201 criminalises access control bypassing for copyrighted works. (like video's at that time)

Under anticircumvention law, it's a crime to alter the functioning of a digital product or service, unless the manufacturer approves of your modification, and – crucially – this is true whether or not your modification violates any other law.

Anticircumvention mandates permission to make adaptations to digital stuff you bought, also if those modifications don't break other laws

Today's links The Post-American Internet: My speech from Hamburg's Chaos Communications Congress. Hey look at this: Delights to delectate. Object permanence: Error code 451; Public email address Mansplaining Lolita; NSA backdoor in Juniper Networks; Don't bug out; Nurses whose shitty boss is a shitty app. Upcoming appearances: Where to find me. Recent appearances: Where I've been. Latest books: You keep readin' em, I'll keep writin' 'em. Upcoming books: Like I said, I'll keep writin' 'em. Colophon: All the rest. The Post-American Internet (permalink) On December 28th, I delivered a speech entitled "A post-American, enshittification-resistant internet" for 39C3, the 39th Chaos Communications Congress in Hamburg, Germany. This is the transcript of that speech. Video Playerhttps://archive.org/download/doctorow-39c3/39c3-1421-eng-A_post-American_enshittification-resistant_internet.mp400:0000:0001:01:12Use Up/Down Arrow keys to increase or decrease volume. Many of you know that I'm an activist with the Electronic Frontier Foundation – EFF. I'm about to start my 25th year there. I know that I'm hardly unbiased, but as far as I'm concerned, there's no group anywhere on Earth that does the work of defending our digital rights better than EFF. I'm an activist there, and for the past quarter-century, I've been embroiled in something I call "The War on General Purpose Computing." If you were at 28C3, 14 years ago, you may have heard me give a talk with that title. Those are the trenches I've been in since my very first day on the job at EFF, when I flew to Los Angeles to crash the inaugural meeting of something called the "Broadcast Protection Discussion Group," an unholy alliance of tech companies, media companies, broadcasters and cable operators. They'd gathered because this lavishly corrupt American congressman, Billy Tauzin, had promised them a new regulation – a rule banning the manufacture and sale of digital computers, unless they had been backdoored to specifications set by that group, specifications for technical measures to block computers from performing operations that were dispreferred by these companies' shareholders. That rule was called "the Broadcast Flag," and it actually passed through the American telecoms regulator, the Federal Communications Commission. So we sued the FCC in federal court, and overturned the rule. We won that skirmish, but friends, I have bad news, news that will not surprise you. Despite wins like that one, we have been losing the war on the general purpose computer for the past 25 years. Which is why I've come to Hamburg today. Because, after decades of throwing myself against a locked door, the door that leads to a new, good internet, one that delivers both the technological self-determination of the old, good internet, and the ease of use of Web 2.0 that let our normie friends join the party, that door has been unlocked. Today, it is open a crack. It's open a crack! And here's the weirdest part: Donald Trump is the guy who's unlocked that door. Oh, he didn't do it on purpose! But, thanks to Trump's incontinent belligerence, we are on the cusp of a "Post-American Internet," a new digital nervous system for the 21st century. An internet that we can build without worrying about America's demands and priorities. Now, don't get me wrong, I'm not happy about Trump or his policies. But as my friend Joey DaVilla likes to say "When life gives you SARS, you make sarsaparilla." The only thing worse than experiencing all the terror that Trump has unleashed on America and the world would be going through all that and not salvaging anything out of the wreckage. That's what I want to talk to you about today: the post-American Internet we can wrest from Trump's chaos. A post-American Internet that is possible because Trump has mobilized new coalition partners to join the fight on our side. In politics, coalitions are everything. Any time you see a group of people suddenly succeeding at a goal they have been failing to achieve, it's a sure bet that they've found some coalition partners, new allies who don't want all the same thing as the original forces, but want enough of the same things to fight on their side. That's where Trump came from: a coalition of billionaires, white nationalists, Christian bigots, authoritarians, conspiratorialists, imperialists, and self-described "libertarians" who've got such a scorching case of low-tax brain worms that they'd vote for Mussolini if he'd promise to lower their taxes by a nickel. And what's got me so excited is that we've got a new coalition in the War on General Purpose Computers: a coalition that includes the digital rights activists who've been on the lines for decades, but also people who want to turn America's Big Tech trillions into billions for their own economy, and national security hawks who are quite rightly worried about digital sovereignty. My thesis here is that this is an unstoppable coalition. Which is good news! For the first time in decades, victory is in our grasp.

Sees the original fight by digital rights activists now joined by geopolitical economics and international cybersec. Thinks this combi will win out

are on the cusp of a "Post-American Internet," a new digital nervous system for the 21st century. An internet that we can build without worrying about America's demands and priorities.

"post-American internet"

that door has been unlocked. Today, it is open a crack. It's open a crack! And here's the weirdest part: Donald Trump is the guy who's unlocked that door.

proposition of this talk: Trump's tariffs mean we can ditch some of the things we accepted the past years wrt computing to avoid them.

been embroiled in something I call "The War on General Purpose Computing.

Cory mentions this as a leading theme, to make sure everyone knows and acts on the fact that computers are general purpose machines, and can run any software. Whereas vendors lock things down, as do employers.

Prince Escalus. Seal up the mouth of outrage for a while, 3190Till we can clear these ambiguities, And know their spring, their head, their true descent; And then will I be general of your woes,

Prince longs for settlement of the feud between the Capulets and the Montagues.

Prince Escalus. A glooming peace this morning with it brings; The sun, for sorrow, will not show his head: Go hence, to have more talk of these sad things; Some shall be pardon'd, and some punished: For never was a story of more woe 3285Than this of Juliet and her Romeo.

Conclusion. Prince's final words: "A glooming peace" - a sad peace comes. The Prince says this is the saddest story ever.

Capulet. O brother Montague, give me thy hand: This is my daughter's jointure, for no more Can I demand. Montague. But I can give thee more: For I will raise her statue in pure gold; 3275That while Verona by that name is known, There shall no figure at such rate be set As that of true and faithful Juliet.

Theme of Resolution. The two families finally make peace. The Capulets and Montagues end their feud. They'll build gold statues of Romeo and Juliet.

all are punish'd.

Theme of suffering because of the feud: Everyone suffers because of the feud.

Prince Escalus. This letter doth make good the friar's words, Their course of love, the tidings of her death: And here he writes that he did buy a poison Of a poor 'pothecary, and therewithal Came to this vault to die, and lie with Juliet. 3265Where be these enemies? Capulet! Montague! See, what a scourge is laid upon your hate, That heaven finds means to kill your joys with love. And I for winking at your discords too Have lost a brace of kinsmen: all are punish'd.

Theme of conflict between the Capulets and the Montagues. Prince blames the two families. The feud caused all the deaths. "Heaven finds means to kill your joys with love."

Page. He came with flowers to strew his lady's grave; And bid me stand aloof, and so I did: Anon comes one with light to ope the tomb; And by and by my master drew on him; And then I ran away to call the watch.

Plot: Page's story. The page explains Paris was just mourning when Romeo arrived.

Balthasar. I brought my master news of Juliet's death; And then in post he came from Mantua To this same place, to this same monument. This letter he early bid me give his father, 3250And threatened me with death, going in the vault, I departed not and left him there.

Plot: Balthasar's story. Balthasar confirms he told Romeo Juliet was dead.

Friar Laurence. I will be brief, for my short date of breath Is not so long as is a tedious tale. 3205Romeo, there dead, was husband to that Juliet; And she, there dead, that Romeo's faithful wife: I married them; and their stol'n marriage-day Was Tybalt's dooms-day, whose untimely death Banish'd the new-made bridegroom from the city, 3210For whom, and not for Tybalt, Juliet pined. You, to remove that siege of grief from her, Betroth'd and would have married her perforce To County Paris: then comes she to me, And, with wild looks, bid me devise some mean 3215To rid her from this second marriage, Or in my cell there would she kill herself. Then gave I her, so tutor'd by my art, A sleeping potion; which so took effect As I intended, for it wrought on her 3220The form of death: meantime I writ to Romeo, That he should hither come as this dire night, To help to take her from her borrow'd grave, Being the time the potion's force should cease. But he which bore my letter, Friar John, 3225Was stay'd by accident, and yesternight Return'd my letter back. Then all alone At the prefixed hour of her waking, Came I to take her from her kindred's vault; Meaning to keep her closely at my cell, 3230Till I conveniently could send to Romeo: But when I came, some minute ere the time Of her awaking, here untimely lay The noble Paris and true Romeo dead. She wakes; and I entreated her come forth, 3235And bear this work of heaven with patience: But then a noise did scare me from the tomb; And she, too desperate, would not go with me, But, as it seems, did violence on herself. All this I know; and to the marriage

Plot Summary: Friar explains everything: the marriage, the potion plan, the failed letter.

Friar Laurence. I am the greatest, able to do least, Yet most suspected, as the time and place Doth make against me of this direful murder; 3200And here I stand, both to impeach and purge Myself condemned and myself excused.

Friar admits he's involved but will explain.

Capulet. O heavens! O wife, look how our daughter bleeds! 3175This dagger hath mista'en—for, lo, his house Is empty on the back of Montague,— And it mis-sheathed in my daughter's bosom!

Discovery: Capulet realizes Juliet stabbed herself with a Montague dagger.

Capulet. What should it be, that they so shriek abroad? Lady Capulet. The people in the street cry Romeo, Some Juliet, and some Paris; and all run, 3165With open outcry toward our monument.

Plot: The Capulets arrive hearing rumors about the sudden death of Romeo, Juliet and Paris.

Third Watchman. Here is a friar, that trembles, sighs and weeps: 3155We took this mattock and this spade from him, As he was coming from this churchyard side.

Plot: The Friar is captured with tools from the tomb.

First Watchman. The ground is bloody; search about the churchyard: Go, some of you, whoe'er you find attach. Pitiful sight! here lies the county slain, And Juliet bleeding, warm, and newly dead, Who here hath lain these two days buried.

Plot: The Watch discovers all three bodies.

there rust, and let me die.

Metaphor: The dagger will rust in her body as she dies. She eventually dies.

What's here? a cup, closed in my true love's hand? Poison, I see, hath been his timeless end: 3125O churl! drunk all, and left no friendly drop

Plot: Juliet sees Romeo dead with the poison cup.

Juliet. Go, get thee hence, for I will not away.

Juliet disobeys the Friar. She's determined to stay.

Balthasar. Here's one, a friend, and one that knows you well. Friar Laurence. Bliss be upon you! Tell me, good my friend, 3075What torch is yond, that vainly lends his light To grubs and eyeless skulls? as I discern, It burneth in the Capel's monument. Balthasar. It doth so, holy sir; and there's my master, One that you love.

Plot: Balthasar reveals Romeo is in the tomb.

A dateless bargain to engrossing death! Come, bitter conduct, come, unsavoury guide! Thou desperate pilot, now at once run on The dashing rocks thy sea-sick weary bark!

Metaphor: Poison is a "pilot" guiding his "ship" (life) to destruction.

And shake the yoke of inauspicious stars

Theme: Fate. Romeo will escape his bad destiny by dying.

That unsubstantial death is amorous, And that the lean abhorred monster keeps 3050Thee here in dark to be his paramour?

Personification: Romeo thinks Death keeps Juliet beautiful because he is in love with her.

Call this a lightning? O my love! my wife! Death, that hath suck'd the honey of thy breath, Hath had no power yet upon thy beauty: Thou art not conquer'd; beauty's ensign yet 3040Is crimson in thy lips and in thy cheeks, And death's pale flag is not advanced there.

Imagery: Juliet's lips and cheeks are still red, not pale like death.

A grave? O no! a lantern, slaughter'd youth, For here lies Juliet, and her beauty makes 3030This vault a feasting presence full of light.

Metaphor: Romeo says Juliet's beauty makes the dark tomb bright like a lantern-lit party hall.

Page. O Lord, they fight! I will go call the watch.

Page prays for them to stop fighting for Juliet.

Paris. O, I am slain! [Falls] 3015If thou be merciful, Open the tomb, lay me with Juliet.

Paris's dying wish. Paris asks to be laid next to Juliet. He loved her until the end.

Paris. This is that banish'd haughty Montague, That murder'd my love's cousin, with which grief, It is supposed, the fair creature died; 2990And here is come to do some villanous shame To the dead bodies: I will apprehend him.

Paris confronts Romeo because of misunderstanding: Paris thinks Romeo is there to destroy the dead bodies including Juliet's body.

Romeo. Thou detestable maw, thou womb of death, Gorged with the dearest morsel of the earth, Thus I enforce thy rotten jaws to open, 2985And, in despite, I'll cram thee with more food!

Metaphor: Romeo talks to the tomb like it is an hungry monster that ate Juliet.

Give me the light: upon thy life, I charge thee, Whate'er thou hear'st or seest, stand all aloof, And do not interrupt me in my course. Why I descend into this bed of death, 2965Is partly to behold my lady's face; But chiefly to take thence from her dead finger A precious ring, a ring that I must use In dear employment: therefore hence, be gone: But if thou, jealous, dost return to pry 2970In what I further shall intend to do, By heaven, I will tear thee joint by joint And strew this hungry churchyard with thy limbs: The time and my intents are savage-wild, More fierce and more inexorable far 2975Than empty tigers or the roaring sea.

Romeo threatens Balthasar. Romeo is desperate and violent. He threatens to tear Balthasar apart if he follows.

Romeo. Give me that mattock and the wrenching iron. Hold, take this letter; early in the morning 2960See thou deliver it to my lord and father. Give me the light: upon thy life, I charge thee, Whate'er thou hear'st or seest, stand all aloof, And do not interrupt me in my course. Why I descend into this bed of death,

Plot: Romeo has a crowbar (mattock) to open the tomb.

Hold, take this letter; early in the morning 2960See thou deliver it to my lord and father.

Plot: Romeo writes a letter to his father explaining everything.

Paris. Sweet flower, with flowers thy bridal bed I strew,— O woe! thy canopy is dust and stones;— Which with sweet water nightly I will dew, Or, wanting that, with tears distill'd by moans: The obsequies that I for thee will keep 2950Nightly shall be to strew thy grave and weep.

Paris's love for Juliet was genuine.

Paris. Sweet flower, with flowers thy bridal bed I strew,— O woe! thy canopy is dust and stones;— Which with sweet water nightly I will dew, Or, wanting that, with tears distill'd by moans: The obsequies that I for thee will keep 2950Nightly shall be to strew thy grave and weep.

Paris's grief: Paris truly loved Juliet. He visits her grave every night with flowers and tears.

Page. [Aside] I am almost afraid to stand alone Here in the churchyard; yet I will adventure.

Setting: Page is scared. The churchyard at night is scary.

Paris. Give me thy torch, boy: hence, and stand aloof: Yet put it out, for I would not be seen. 2935Under yond yew-trees lay thee all along, Holding thine ear close to the hollow ground; So shall no foot upon the churchyard tread, Being loose, unfirm, with digging up of graves, But thou shalt hear it: whistle then to me, 2940As signal that thou hear'st something approach. Give me those flowers. Do as I bid thee, go.

Paris at the tomb: Paris is mourning Juliet. He's being secretive.

Friar Laurence. Now must I to the monument alone; 2925Within three hours will fair Juliet wake: She will beshrew me much that Romeo Hath had no notice of these accidents;

Friar's new plan. Friar Laurence takes action. He'll go get Juliet himself since Romeo doesn't know the truth.

The letter was not nice but full of charge Of dear import, and the neglecting it May do much danger. Friar John, go hence; 2920Get me an iron crow, and bring it straight Unto my cell.

Plot: The important letter. The letter explained Juliet wasn't really dead.

Friar Laurence. Unhappy fortune! by my brotherhood,

Theme: Bad luck. This accident causes the tragedy.

Here in this city visiting the sick, And finding him, the searchers of the town, Suspecting that we both were in a house Where the infectious pestilence did reign, 2910Seal'd up the doors, and would not let us forth; So that my speed to Mantua there was stay'd.

Plot Device: Friar John was quarantined because of plague fears. He couldn't deliver the letter.

Come, cordial and not poison, go with me To Juliet's grave; for there must I use thee.

Irony: Romeo calls the poison a "cordial" (medicine) because he believes it will reunite him with Juliet in death.

Romeo. There is thy gold, worse poison to men's souls, Doing more murders in this loathsome world, Than these poor compounds that thou mayst not sell. I sell thee poison; thou hast sold me none. Farewell: buy food, and get thyself in flesh.

Romeo's speech about gold. Theme: Money is worse than poison. Gold causes more evil in the world.

Apothecary. My poverty, but not my will, consents.

The apothecary only agrees because he's poor, not because he wants to since the law of Mantua forbids selling poison.

Romeo. Art thou so bare and full of wretchedness, And fear'st to die? famine is in thy cheeks, 2880Need and oppression starveth in thine eyes, Contempt and beggary hangs upon thy back; The world is not thy friend nor the world's law; The world affords no law to make thee rich; Then be not poor, but break it, and take this.

Romeo convinces the apothecary with the following argument. He says, since apothecary is so poor and starving, he should break the law for money.

Apothecary. Such mortal drugs I have; but Mantua's law Is death to any he that utters them.

Setting and the law then: Selling poison is punishable by death in Mantua.

Romeo. Come hither, man. I see that thou art poor: Hold, there is forty ducats: let me have 2870A dram of poison, such soon-speeding gear As will disperse itself through all the veins That the life-weary taker may fall dead And that the trunk may be discharged of breath As violently as hasty powder fired 2875Doth hurry from the fatal cannon's womb.

Romeo bribes the poor Apothecary with 40 ducats, which was lot of money during that time.

I do remember an apothecary,— And hereabouts he dwells,—which late I noted In tatter'd weeds, with overwhelming brows, Culling of simples; meagre were his looks, Sharp misery had worn him to the bones: 2850And in his needy shop a tortoise hung, An alligator stuff'd, and other skins Of ill-shaped fishes; and about his shelves A beggarly account of empty boxes, Green earthen pots, bladders and musty seeds, 2855Remnants of packthread and old cakes of roses, Were thinly scatter'd, to make up a show.

Imagery: Shakespeare describes a poor, dirty shop with strange items. It shows poverty in that place.

Balthasar. Then she is well, and nothing can be ill: Her body sleeps in Capel's monument, And her immortal part with angels lives. 2825I saw her laid low in her kindred's vault, And presently took post to tell it you:

Plot: Balthasar tells Romeo Juliet is dead. He saw her put in the Capulet tomb.

My dreams presage some joyful news at hand: My bosom's lord sits lightly in his throne; And all this day an unaccustom'd spirit Lifts me above the ground with cheerful thoughts.

Romeo is hopeful. He had a good dream and feels happy for the first time.

this is something I may want to pick up again as side project, while fixing webfinger settings for my blog. It also seems that I switched it off again at some point, or that the Masto search has changed in such a way it no longer works as it did in 2022.

My 2019 talk in Belgium on measuring open data impact. Might be relevant for the conf on #2026/01/22 I'm attending.

Accusing the George Floyd Protests and not the wave of death and destruction caused by the COVID pandemic and our lackadaisical covid policies is fucking wild and racist. You can also look at police slowdowns that took place after the George Floyd protests. The security apparatus requires you to be in fear and feel a need for them, even if they don't really do anything.

[[Too Much To Know by Ann Blair]] 2010, available through Kobo Plus, or 20e for the ebook. "Managing Scholarly Information before the Modern Age"

Ann Blair 1992 on Common place books. https://doi.org/10.2307/2709935

Humanist Methods in Natural Philosophy: The Commonplace Book in Zotero

Ann Blair 2010

Added The Rise of Note‐Taking in Early Modern Europe in Zotero

On Masto this author mentioned he had reason to believe the UK government would ban X/Grok within 2 weeks. I don't see a particular direct legal path for that, other than CSAM spreading as platform which is a criminal offence.

Aktuell besteht die Gefahr, dass der „Digitale Omnibus“ die Fristen um mindestens ein weiteres Jahr verschiebt.

The digital omnibus migth postpone that date of August. (Check, bc does the EC have a right to change the applicability on its own, or does it need a trilogue outcome for it?

Wenn Grok also Bilder generiert und auf X veröffentlicht, ohne sie als Deepfake zu kennzeichnen, verstößt das gegen EU-Recht - jedenfalls ab August 2026, wenn die relevanten Vorschriften anwendbar werden.

The relevant parts of the AI reg wrt fakes will be applicable in #2026/08

Article by Markus Beckedahl et al on the same Grok situtation. Here AI Act does get a mention, and some lines to GDPR and copyright laws too.

System Context Diagram

A context diagram is a high-level, simplified flowchart showing a system as a single process (a circle) and its interactions (data flows) with external entities (people, other systems, etc.), defining the system's boundaries and scope for stakeholders, and serving as the Level 0 Data Flow Diagram (DFD) for understanding the big picture before detailed design.

Nature Medicine "A minimally invasive dried blood spot biomarker test for the detection of Alzheimer's disease pathology" Jan 5, 2026. The abstract does not mention the 10-20yr early warning finding.

This is the actual link https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-025-04080-0

Yet, further refinement of collection and analytical protocols is needed to fully translate this approach to be viable and useful as a clinical tool.

However, not yet at the stage this can be used as a clinical tool for diagnostics.

indings underscore the potential of dried blood collection and capillary blood as a minimally invasive, scalable approach for AD biomarker testing in research settings

For research dried capillary blood collection is useful and minimally invasive.

The study also explored unsupervised blood collection, finding high concordance between supervised and self-collected samples.

The study looked at self-administered blood collection too.

DROP-AD project investigates the potential of dried plasma spot (DPS) and dried blood spot (DBS) analysis, derived from capillary blood, for detecting AD biomarkers,

The project this paper is a result of looks at the utility of dried blood spots and plasma spots for analysis.

Yet, the logistics surrounding venipuncture for blood collection, although considerably simpler than the acquisition of imaging and CSF, require precise processing and storage specific to AD biomarkers that are still guided by medical personnel. Consequently, limitations in their widescale use in research and broader clinical implementation exist. T

Problem statement is that while blood tests are an easy method, there are limits on widescale use, due to some specific cares needing to be taken in the process.

[[Cory Doctorow p]] oped in Guardian, on US tech policy and enshittification. Points out that the US basically reneged on a deal (no tariffs if you allow our tech, but now we have the tariffs) so we can renege our part of it (circumvention laws). This aimed at UK audience, points out that that circumvention is inside a EU reg (art 6 of Copyright and Information Society Directive 2001) so it would be relatively easy after brexit to ditch the thing

Note 2001/29 has been amended by Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market 2019/790, but I don't think in this aspect.

More generally, “efficiency” has proved brittlein the pandemic, as “just-in-time” systems with little “slack”shut down rapidly. Resilience and adaptability

ETTO and Nuclear plant redundancies and safety nets.

The FEC critique the “supply-side” approach to growth, both asineffective in providing these elusive “good jobs” and in assum-ing aggregate GDP will “will lift all boats”. The FEC’s goal is toreorient social and economic policy away from a GDP-centred,individualised jobs-and-wages growth to a focus on guaranteedcollective liveability.It is disposable household income, rather than wages perse, that should provide a key metric.

Watch out with displacing definitions and invisibilising the most vulnerable. Who would get to say what accounts as "disposable"? What is "needed" insofar as to be counted only as undisposable: Shelter, food, education? I think I get, though, that all these basic undisposable needs, shall be given to everyone, collectively. But this is already in place as a right, just not enforced whatsoever...

How, then, do we reassert culture’s role in public policy?Many who seek to give culture a distinct function have beentempted to add it as a measure or priority alongside the “eco-nomic”. Advocacy such as the “fourth pillar” adds culture tothe “triple bottom line” of economic, social, and environmen-tal impact. But simply adding “culture” leaves “economy”unexamined, a “black box”.6 Like many such attempts, it isconstantly surprised when the real bottom line turns out to be“economy” after all. 7 In this sense, we need to challenge what“economy” actually entails.

"Economy" reeks of instrumentalism. Granted, it is needed for efficiency, to "save" lives, to "care" for the largest amount, but most of the time, it's not used in this particular efficiency way.

A home bloodtest has been developed at Göteborg Uni with international partners, to check for brain changes 10-20yrs before any dementia symptoms become apparent. This chimes w. other research I saw wrt changes in banking transactions 10yr before symptoms, and early changes in the spatial brain. Can I find publications? The .se researcher is Henrik Zetterberg

Clear headed explanation of DSA wrt Grok and X. Otoh in the case of Grok, I think the AI Act has a role to play, which is directly and more immediately connected to market access of Grok. It only takes into account the DSA, and the AIR isn't fully applicable yet, but still I think the entire framework needs to be taken into account. Incl the GDPR.

the

Artistic and Iconographic Motifs: olmecs

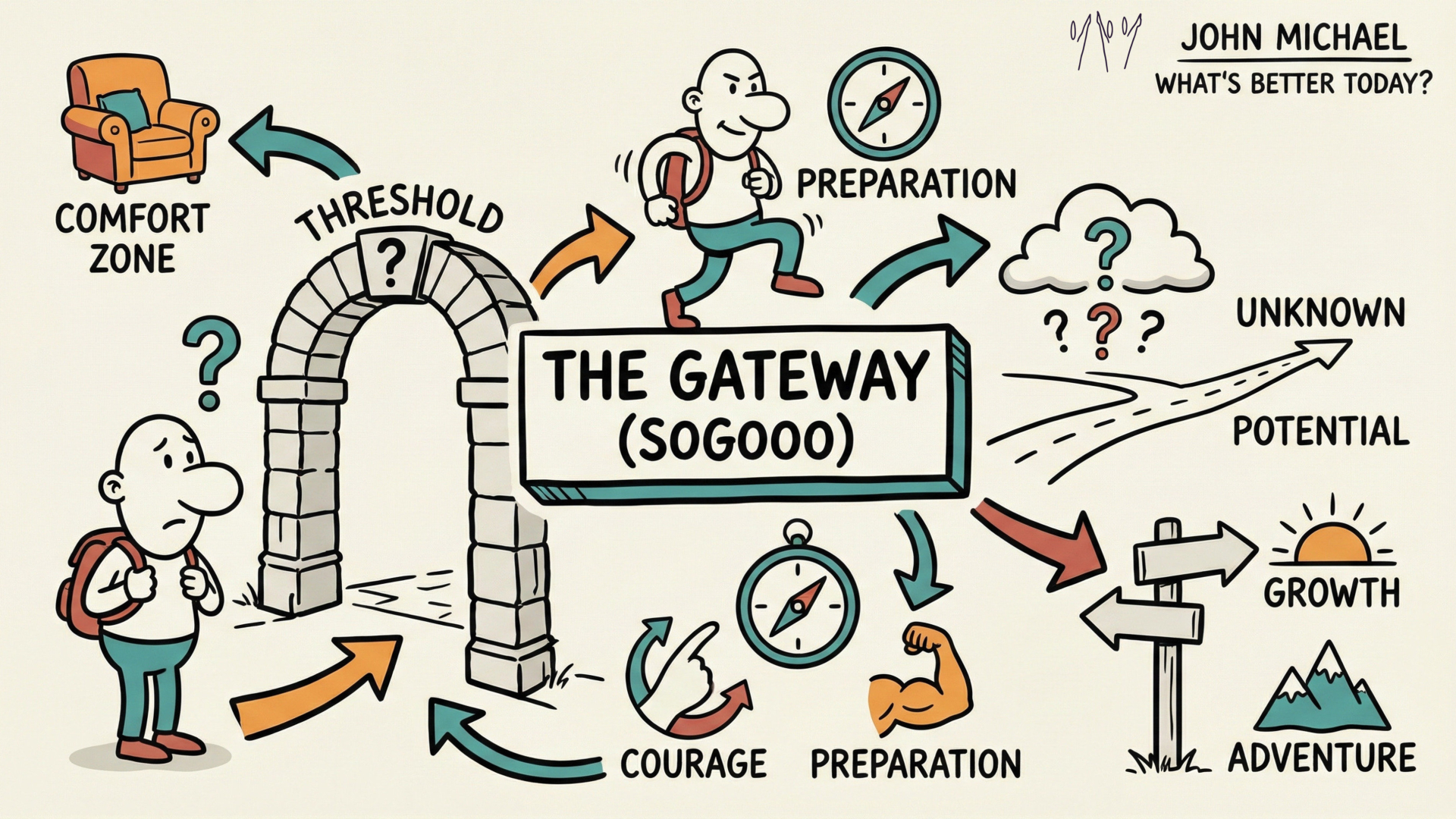

p.s. Want the visual map? You'll find a full FieldNote Sketch Summary of this inside the 'hidden' layer. Click this highlight to see the synthesis, share it with someone you know needs it and save a copy for yourself.

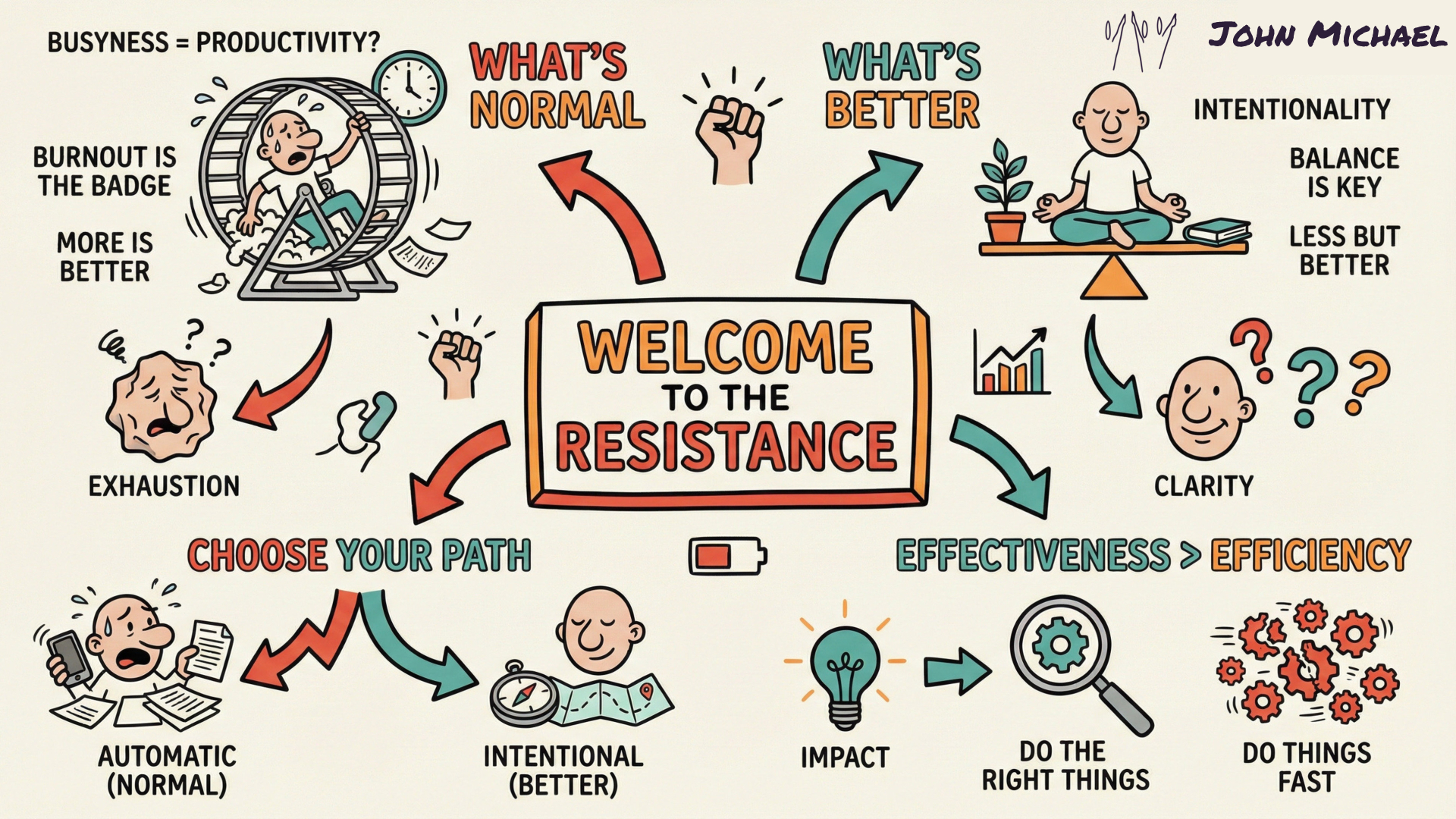

You made it to the end. Here is the map of the territory we just covered.

Save it, share it, or keep it as a reminder that the Resistance is just proof that you’re onto something big.

Save it, share it, or keep it as a reminder that the Resistance is just proof that you’re onto something big.

The Override Protocol You cannot out-argue the loop; you must overwrite it with Source Code.

This is the pivot. Everything changes when we spot the lie. If you're stuck here, use the counter-measure - it seems to easy to fix it, but it works!

We tend to think our demons are complex

I almost didn't hit publish on this. The Resistance told me it was too 'woo-woo' or too niche. If you're feeling that 'not-enoughness' right now, you’re in the right place.

THE RESISTANCE

For me, Resistance usually looks like a notification ping that distracts my attention right in the middle of my "flow" when I'm writing or sketching. What does your 'gatekeeper' look like today?"

7. ORDER BY If an order is specified by the ORDER BY clause, the rows are then sorted by the specified data in either ascending or descending order. Since all the expressions in the SELECT part of the query have been computed, you can reference aliases in this clause. 8. LIMIT / OFFSET Finally, the rows that fall outside the range specified by the LIMIT and OFFSET are discarded, leaving the final set of rows to be returned from the query.

最后先 order by 再 limit / offset

5. SELECT Any expressions in the SELECT part of the query are finally computed. 6. DISTINCT Of the remaining rows, rows with duplicate values in the column marked as DISTINCT will be discarded.

接下来先 select 再 distinct

If the query has a GROUP BY clause, then the constraints in the HAVING clause are then applied to the grouped rows, discard the grouped rows that don't satisfy the constraint. Like the WHERE clause, aliases are also not accessible from this step in most databases.

接下来是 having,进一步过滤 group by 之后的结果。

having 可以拿到聚合函数的值,但是不能使用 select 之后的别名。

As a result of the grouping, there will only be as many rows as there are unique values in that column. Implicitly, this means that you should only need to use this when you have aggregate functions in your query.

接下来是 group by,只有用聚合函数的时候才需要使用 group by

Each of the constraints can only access columns directly from the tables requested in the FROM clause. Aliases in the SELECT part of the query are not accessible in most databases since they may include expressions dependent on parts of the query that have not yet executed.

第一道执行的是 where 语句,只能获取到 from 语句里得到的列,select 里的别名获取不到

1. FROM and JOINs The FROM clause, and subsequent JOINs are first executed to determine the total working set of data that is being queried. This includes subqueries in this clause, and can cause temporary tables to be created under the hood containing all the columns and rows of the tables being joined.

from 和 join 第一个被执行,用来确定 working data set

如果有子查询的话会执行

Luckily, SQL allows us to do this by adding an additional HAVING clause which is used specifically with the GROUP BY clause to allow us to filter grouped rows from the result set.

HAVING 语句是用来 filter group by 之后的结果

COUNT(*), COUNT(column) A common function used to counts the number of rows in the group if no column name is specified. Otherwise, count the number of rows in the group with non-NULL values in the specified column.

count 组内的数量,* 是所有,指定了列就是 non-NULL 的行

Without a specified grouping, each aggregate function is going to run on the whole set of result rows and return a single value.

如果不带 grouping 的话,就是在整个表上计算,返回一个结果

In addition to the simple expressions that we introduced last lesson, SQL also supports the use of aggregate expressions (or functions) that allow you to summarize information about a group of rows of data.

aggregation 是聚合一系列的行

Sometimes, it's also not possible to avoid NULL values, as we saw in the last lesson when outer-joining two tables with asymmetric data.

有时候 null 是不可避免的,比如 join 的时候两张表的 asymmetric

In such cases, SQL provides a convenient way to discard rows that have a duplicate column value by using the DISTINCT keyword.

distinct the combination or the first following column?

answer: the combination

Another clause which is commonly used with the ORDER BY clause are the LIMIT and OFFSET clauses, which are a useful optimization to indicate to the database the subset of the results you care about. The LIMIT will reduce the number of rows to return, and the optional OFFSET will specify where to begin counting the number rows from.

limit 限制 return 的行数 offset 制定从哪开始 count row

offset 从 1 开始:limit 1 offset 1 返回第二个

When an ORDER BY clause is specified, each row is sorted alpha-numerically based on the specified column's value. In some databases, you can also specify a collation to better sort data containing international text.

by default it's sorted alpha-numerically

some db provide collation for better sorting for i18n text, but what?

Some of the buildings are new, so they don't have any employees in them yet, but we need to find some information about them regardless.

this is an example of growing independently:

new building can be without employees

You might see queries with these joins written as LEFT OUTER JOIN, RIGHT OUTER JOIN, or FULL OUTER JOIN, but the OUTER keyword is really kept for SQL-92 compatibility and these queries are simply equivalent to LEFT JOIN, RIGHT JOIN, and FULL JOIN respectively.

outer 关键字是和 SQL-92 兼容,等同于不写

When joining table A to table B, a LEFT JOIN simply includes rows from A regardless of whether a matching row is found in B. The RIGHT JOIN is the same, but reversed, keeping rows in B regardless of whether a match is found in A. Finally, a FULL JOIN simply means that rows from both tables are kept, regardless of whether a matching row exists in the other table.

left join right join full join

For example, the arts can connect to school concerns such as character education/bullying, collaboration, habits of mind, or multiple intelligences.

I love that the arts can be used to describe various topics!!

By their nature, the arts engage students in learning through observing, listening, and moving and offer learners various ways to acquire information and act on it to build understanding

This is an amazing idea that arts can provide to us in the classroom. It is so awesome that these skills are all used to help students gain a better understanding.

You might see queries where the INNER JOIN is written simply as a JOIN. These two are equivalent, but we will continue to refer to these joins as inner-joins because they make the query easier to read once you start using other types of joins,

inner join is join

After the tables are joined, the other clauses we learned previously are then applied.

first join

and allows for data in the database to grow independently of each other (ie. Types of car engines can grow independent of each type of car). As a trade-off, queries get slightly more complex since they have to be able to find data from different parts of the database, and performance issues can arise when working with many large tables.

normalization pros and cons

the Parisian soul

"The Parisian soul" .... Jayzus. "Wine-stained" ... please, no.

= Case sensitive exact string comparison (notice the single equals) col_name = "abc"

In addition to making the results more manageable to understand, writing clauses to constrain the set of rows returned also allows the query to run faster due to the reduction in unnecessary data being returned.

返回的行数少了,SQL 就快了是吗?

My colleagues and I at Sourcegraph are firmly in the camp that believes that you are the agent who will wrangle the task graph, above the level of the leaf nodes. We believe the wrangler will be human, not a model. We are not sitting around to wait for the research on autonomous agent

He seems to have shifted that position over the last year (Gas Town and other efforts)

Tức mình hắn chửi ngay tất cả làng Vũ Ðại. Nhưng cả làng Vũ Ðại ai cũng nhủ, "Chắc nó trừ mình ra!" Không ai lên tiếng cả.

Tiếng chửi của Chí Phèo thể hiện sự cô độc của một con người bị xã hội ruồng bỏ