Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

Public reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors provide a resource to the systems neuroscience community, by offering their Python-based CLoPy platform for closed-loop feedback training. In addition to using neural feedback, as is common in these experiments, they include a capability to use real-time movement extracted from DeepLabCut as the control signal. The methods and repository are detailed for those who wish to use this resource. Furthermore, they demonstrate the efficacy of their system through a series of mesoscale calcium imaging experiments. These experiments use a large number of cortical regions for the control signal in the neural feedback setup, while the movement feedback experiments are analyzed more extensively.

Strengths:

The primary strength of the paper is the availability of their CLoPy platform. Currently, most closed-loop operant conditioning experiments are custom built by each lab and carry a relatively large startup cost to get running. This platform lowers the barrier to entry for closed-loop operant conditioning experiments, in addition to making the experiments more accessible to those with less technical expertise.

Another strength of the paper is the use of many different cortical regions as control signals for the neurofeedback experiments. Rodent operant conditioning experiments typically record from the motor cortex and maybe one other region. Here, the authors demonstrate that mice can volitionally control many different cortical regions not limited to those previously studied, recording across many regions in the same experiment. This demonstrates the relative flexibility of modulating neural dynamics, including in non-motor regions.

Finally, adapting the closed-loop platform to use real-time movement as a control signal is a nice addition. Incorporating movement kinematics into operant conditioning experiments has been a challenge due to the increased technical difficulties of extracting real-time kinematic data from video data at a latency where it can be used as a control signal for operant conditioning. In this paper they demonstrate that the mice can learn the task using their forelimb position, at a rate that is quicker than the neurofeedback experiments.

Weaknesses:

There are several weaknesses in the paper that diminish the impact of its strengths. First, the value of the CLoPy platform is not clearly articulated to the systems neuroscience community. Similarly, the resource could be better positioned within the context of the broader open-source neuroscience community. For an example of how to better frame this resource in these contexts, I recommend consulting the pyControl paper. Improving this framing will likely increase the accessibility and interest of this paper to a less technical neuroscience audience, for instance by highlighting the types of experimental questions CLoPy can enable.

We appreciate the editor’s feedback regarding the clarity of the CLoPy platform's value and its positioning within the broader neuroscience community. We agree and understand the importance of effectively communicating the utility of CLoPy to both the systems neuroscience field and the wider open-source neuroscience community.

To address this, we have revised the introduction and discussion sections of the manuscript to more clearly articulate the unique contributions of the CLoPy platform. Specifically:

(1) We have emphasized how CLoPy can address experimental questions in systems neuroscience by highlighting its ability to enable real-time closed-loop experiments, such as investigating neural dynamics during behavior or studying adaptive cortical reorganization after injury. These examples are aimed at demonstrating its practical utility to the neuroscience audience.

(2) We have positioned CLoPy within the broader open-source neuroscience ecosystem, drawing comparisons to similar resources like pyControl. We describe how CLoPy complements existing tools by focusing on real-time optical feedback and integration with genetically encoded indicators, which are becoming increasingly popular in systems neuroscience. We also emphasize its modularity and ease of adoption in experimental settings with limited resources.

(3) To make the manuscript more accessible to a less technically inclined audience, we have restructured certain sections to focus on the types of experiments CLoPy enables, rather than the technical details of the implementation.

We have consulted the pyControl paper, as suggested, and have used it as a reference point to improve the framing of our resource. We believe these changes will increase the accessibility and appeal of the paper to a broader neuroscience audience.

While the dataset contains an impressive amount of animals and cortical regions for the neurofeedback experiment, and an analysis of the movement-feedback experiments, my excitement for these experiments is tempered by the relative incompleteness of the dataset, as well as its description and analysis in the text. For instance, in the neurofeedback experiment, many of these regions only have data from a single mouse, limiting the conclusions that can be drawn. Additionally, there is a lack of reporting of the quantitative results in the text of the document, which is needed to better understand the degree of the results. Finally, the writing of the results section could use some work, as it currently reads more like a methods section.

Thank you for your thoughtful and constructive feedback on our manuscript. We appreciate the time and effort you took to review our work and provide detailed suggestions for improvement. Below, we address the key points raised in your review:

(1) Dataset Completeness: We acknowledge that some of the neurofeedback experiments include data from only a single mouse for some cortical regions while for some cortical regions, there are several animals. This was due to practical constraints during the study, and we understand the limitations this poses for drawing broad conclusions. We felt it was still important to include these data sets with smaller sample sizes as they might be useful for others pursuing this direction in the future. To address this, we have revised the text to explicitly acknowledge these limitations and clarify that the results for some regions are exploratory in nature. We believe our flexible tool will provide a means for our lab and others include more animals representing additional cortical regions in future studies. Importantly, we have included all raw and processed data as well as code for future analysis.

(2) Quantitative Results: We recognize the importance of reporting quantitative results in the text for better clarity and interpretation. In response, we have added more detailed description of the quantitative findings from both the neurofeedback and movement-feedback experiments. This will include effect sizes, statistical measures, and key numerical results to provide a clearer understanding of the degree and significance of the observed effects.

(3) Results Section Writing: We appreciate your observation that parts of the results section read more like a methods section. To improve clarity and focus, we have restructured the results section to present the findings in a more concise and interpretative manner, while moving overly detailed descriptions of experimental procedures to the methods section.

Suggestions for improved or additional experiments, data or analyses:

Not necessary for this paper, but it would be interesting to see if the CLNF group could learn without auditory feedback.

This is a great suggestion and certainly something that could be done in the future.

There are no quantitative results in the results section. I would add important results to help the reader better interpret the data. For example, in: "Our results indicated that both training paradigms were able to lead mice to obtain a significantly larger number of rewards over time," You could show a number, with an appropriate comparison or statistical test, to demonstrate that learning was observed.

Thank you for pointing this out. We have mentioned quantification values in the results now, along with being mentioned in the figure legends, and we are quoting it in following sentences. “A ΔF/F0 threshold value was calculated from a baseline session on day 0 that would have allowed 25% performance. Starting from this basal performance of around 25% on day 1, mice (CLNF No-rule-change, N=23, n=60 and CLNF Rule-change, N=17, n=60) were able to discover the task rule and perform above 80% over ten days of training (Figure 4A, RM ANOVA p=2.83e-5), and Rule-change mice even learned a change in ROIs or rule reversal (Figure 4A, RM ANOVA p=8.3e-10, Table 5 for different rule changes). There were no significant differences between male and female mice (Supplementary Figure 3A).”

For: "Performing this analysis indicated that the Raspberry Pi system could provide reliable graded feedback within ~63 {plus minus} 15 ms for CLNF experiments." The LED test shows the sending of the signal, but the actual delay for the audio generation might be longer. This is also longer than the 50 ms mentioned in the abstract.

We appreciate the reviewer’s insightful comment. The latency reported (~63ms) was measured using the LED test, which captures the time from signal detection to output triggering on the Raspberry Pi GPIO. We agree that the total delay for auditory feedback generation could include an additional latency component related to the digital-to-analog conversion and speaker response. In our setup, we employ a fast Audiostream library written in C to generate the audio signal and expect the delay contribution to be negligible compared to the GPIO latency. Though we did not do this, it can be confirmed by an oscilloscope-based pilot measurement (for additional delay calculation). We have updated the manuscript to clarify that the 63 ± 15 ms value reflects the GPIO-triggered output latency, and we have revised the abstract to accurately state the delay as “~63 ms” rather than 50 ms. This ensures consistency and avoids underestimation of the latency. We have corrected the LED latency for CLNF and CLMF experiments in the abstract as well.

It could be helpful to visualize an individual trial for each experiment type, for instance how the audio frequency changes as movement speed / calcium activity changes.

We have added Supplementary Figure 8 that contains this data where you can see the target cortical activity trace, target paw speed, rewards, along with the audio frequency generated.

The sample sizes are small (n=1) for a few groups. I am excited by the variety of regions recorded, so it could be beneficial for the authors to collect a few more animals to beef up the sample sizes.

We've acknowledged that some of the sample sizes are small. Importantly, we have included raw and processed data as well as code for future analysis. We felt it was still important to still include these data sets with smaller sample sizes as they might be useful for others pursuing this direction in the future.

I am curious as to why 60 trials sessions were used. Was it mostly for the convenience of a 30 min session, or were the animals getting satiated? If the former, would learning have occurred more rapidly with longer sessions?

This is a great observation and the answer is it was mostly due to logistical reasons. We tried to not keep animals headfixed for more than 45 minutes in each session as they become less engaged with long duration headfixed sessions. After headfixing them, it takes about 15 minutes to get the experiment going and therefore 30 - 40 minutes long recorded sessions seemed appropriate before they stop being engaged or before they get satiated in the task. We provided supplemental water after the sessions and we observed that they consumed water after the sessions so they were not fully satiated during the sessions even when they performed well in the task and got maximum rewards. We also had inter-trial rest periods of 10s that elongated the session duration. We think it would be interesting to explore the relationship between session duration(number of trials) and task learning progression over the days in a separate study.

Figure 4E is interesting, it seems like the changes in the distribution of deltaF was in both positive and negative directions, instead of just positive. I'd be curious as to the author's thoughts as to why this is the case. Relatedly, I don't see Figure 4E, and a few other subplots, mentioned in the text. As a general comment, I would address each subplot in the text.

We have split Figure 4 into two to keep the figures more readable. Previous Figure 4E-H are now Figure 5A-D in the revised manuscript. The online real-time CLNF sessions were using a moving window average to calculate ΔF/F<sub>0</sub> and the figures were generated by averaging the whole recorded sessions. We have added text in Methods under “Online ΔF/F<sub>0</sub>calculation” and “Offline ΔF/F<sub>0</sub> calculation” sections making it clear about how we do our ΔF/F<sub>0</sub> normalization based on average fluorescence over the entire session. Using this method of normalization does increase the baseline so that some peaks appear to be below zero. Additionally, it is unclear what strategy animals are employing to achieve the rule specific target activity. The task did not constrain them to have a specific strategy for cortical activation - they were rewarded as long as they crossed the threshold in target ROI(s). For example, in 2-ROI experiments, to increase ROI1-ROI2 target activity, they could increase activity of ROI1 relative to ROI2 or decreased activity of ROI1 relative to ROI1 - both would have led to a reward as long as the result crossed the threshold.

We have now addressed and added reference to the figures in the text in Results under “Mice can explore and learn an arbitrary task, rule, and target conditions” and “Mice can rapidly adapt to changes in the task rule” sections - thanks for pointing this out.

For: "In general, all ROIs assessed that encompassed sensory, pre-motor, and motor areas were capable of supporting increased reward rates over time," I would provide a visual summary showing the learning curves for the different types of regions.

We have rewritten this section to emphasize that these conclusions were based on pooled data from multiple regions of interest. The sample sizes for each type of region are different and some are missing. We believe it would be incomplete and not comparable to present this as a regular analysis since the sample sizes were not balanced. We would be happy to dive deeper into this and point to the raw and processed dataset if anyone would like to explore this further by GitHub or other queries.

Relatedly, I would further explain the fast vs slow learners, and if they mapped onto certain regions.

Mice were categorized into fast or slow learners based on the slope of learning over days (reward progression over the days) as shown in Supplementary Figure 3C,D. Our initial aim was not to probe cortical regions that led to fast vs slow learning but this was a grouping we did afterwards. Based on the analysis we did, the fast learners included the sensory (V1), somatosensory (BC, HL), and motor (M1, M2) areas, while the slow learners included the motor (M1, M2), and higher order (TR, RL) cortical areas. Testing all dorsal cortical areas would be prudent to establish their role in fast or slow learning and it is an interesting future direction.

Also I would make the labels for these plots (e.g. Supp Fig3) more intuitive, versus the acronyms currently used.

We have made more expressive labels and explained the acronyms below the Supplementary Figure 3.

The CLMF animals showed a decrease in latency across learning, what about the CLNF animals? There is currently no mention in the text or figures.

We have now incorporated the CLNF task latency data into both the Results text and Figure 4C. Briefly, task latency decreased as performance improved, increased following a rule change, and then decreased again as the animals relearned the task. The previous Figure 4C has been updated to Figure 4D, and the former Figure 4D has been moved to Supplementary Figure 4E.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

In this work, Gupta & Murphy present several parallel efforts. On one side, they present the hardware and software they use to build a head-fixed mouse experimental setup that they use to track in "real-time" the calcium activity in one or two spots at the surface of the cortex. On the other side, the present another setup that they use to take advantage of the "real-time" version of DeepLabCut with their mice. The hardware and software that they used/develop is described at length, both in the article and in a companion GitHub repository. Next, they present experimental work that they have done with these two setups, training mice to max out a virtual cursor to obtain a reward, by taking advantage of auditory tone feedback that is provided to the mice as they modulate either (1) their local cortical calcium activity, or (2) their limb position.

Strengths:

This work illustrates the fact that thanks to readily available experimental building blocks, body movement and calcium imaging can be carried using readily available components, including imaging the brain using an incredibly cheap consumer electronics RGB camera (RGB Raspberry Pi Camera). It is a useful source of information for researchers that may be interested in building a similar setup, given the highly detailed overview of the system. Finally, it further confirms previous findings regarding the operant conditioning of the calcium dynamics at the surface of the cortex (Clancy et al. 2020) and suggests an alternative based on deeplabcut to the motor tasks that aim to image the brain at the mesoscale during forelimb movements (Quarta et al. 2022).

Weaknesses:

This work covers 3 separate research endeavors: (1) The development of two separate setups, their corresponding software. (2) A study that is highly inspired from the Clancy et al. 2020 paper on the modulation of the local cortical activity measured through a mesoscale calcium imaging setup. (3) A study of the mesoscale dynamics of the cortex during forelimb movements learning. Sadly, the analyses of the physiological data appears uncomplete, and more generally the paper tends to offer overstatements regarding several points:

In contrast to the introductory statements of the article, closed-loop physiology in rodents is a well-established research topic. Beyond auditory feedback, this includes optogenetic feedback (O'Connor et al. 2013, Abbasi et al. 2018, 2023), electrical feedback in hippocampus (Girardeau et al. 2009), and much more.

We have included and referenced these papers in our introduction section (quoted below) and rephrased the part where our previous text indicated there are fewer studies involving closed-loop physiology.

“Some related studies have demonstrated the feasibility of closed-loop feedback in rodents, including hippocampal electrical feedback to disrupt memory consolidation (Girardeau et al.2009), optogenetic perturbations of somatosensory circuits during behavior (O'Connor et al.2013), and more recent advances employing targeted optogenetic interventions to guide behavior (Abbasi et al. 2023).”

The behavioral setups that are presented are representative of the state of the art in the field of mesoscale imaging/head fixed behavior community, rather than a highly innovative design. In particular, the closed-loop latency that they achieve (>60 ms) may be perceived by the mice. This is in contrast with other available closed-loop setups.

We thank the reviewer for this thoughtful comment and fully agree that our closed-loop latency is larger than that achieved in some other contemporary setups. Our primary aim in presenting this work, however, is not to compete with the lowest possible latencies, but to provide an open-source, accessible, and flexible platform that can be readily adopted by a broad range of laboratories. By building on widely available and lower-cost components, our design lowers the barrier of entry for groups that wish to implement closed-loop imaging and behavioral experiments, while still achieving latencies well within the range that can support many biologically meaningful applications.

For example, our latency (~60 ms) remains compatible with experimental paradigms such as:

Motor learning and skill acquisition, where sensorimotor feedback on the scale of tens to hundreds of milliseconds is sufficient to modulate performance.

Operant conditioning and reward-based learning, in which reinforcement timing windows are typically broader and not critically dependent on sub-20 ms latencies.

Cortical state dependent modulation, where feedback linked to slower fluctuations in brain activity (hundreds of milliseconds to seconds) can provide valuable insight.

Studies of perception and decision-making, in which stimulus response associations often unfold on behavioral timescales longer than tens of milliseconds.

We believe that emphasizing openness, affordability, and flexibility will encourage widespread adoption and adaptation of our setup across laboratories with different research foci. In this way, our contribution complements rather than competes with ultra-low-latency closed-loop systems, providing a practical option for diverse experimental needs.

Through the paper, there are several statements that point out how important it is to carry out this work in a closed-loop setting with an auditory feedback, but sadly there is no "no feedback" control in cortical conditioning experiments, while there is a no-feedback condition in the forelimb movement study, which shows that learning of the task can be achieved in the absence of feedback.

We fully agree that such a control would provide valuable insight into the contribution of feedback to learning in the CLNF paradigm. In designing our initial experiments, we envisioned multiple potential control conditions, including No-feedback and Random-feedback. However, our first and primary objective was to establish whether mice could indeed learn to modulate cortical ROI activation through auditory feedback, and to further investigate this across multiple cortical regions. For this reason, we focused on implementing the CLNF paradigm directly, without the inclusion of these additional control groups. To broaden the applicability of the system, we subsequently adapted the platform to the CLMF experiments, where we did incorporate a No-feedback group. These results, as the reviewer notes, strengthen the evidence for the role of feedback in shaping task performance. We agree that the inclusion of a No-feedback control group in the CLNF paradigm will be crucial in future studies to further dissect the specific contribution of feedback to cortical conditioning.

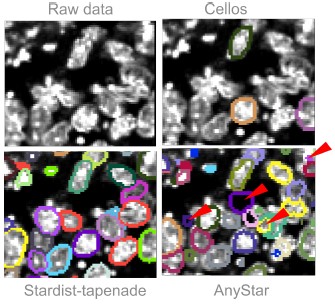

The analysis of the closed-loop neuronal data behavior lacks controls. Increased performance can be achieved by modulating actively only one of the two ROIs, this is not clearly analyzed (for instance looking at the timing of the calcium signal modulation across the two ROIs. It seems that overall ROIs1 and 2 covariate, in contrast to Clancy et al. 2020. How can this be explained?

We agree that the possibility of increased performance being driven by modulation of a single ROI is an important consideration. Our study indeed began with 1-ROI closed-loop experiments. In those early experiments, while we did observe animals improving performance across days, we realized that daily variability in ongoing cortical GCaMP activity could lead to fluctuations in threshold-crossing events. The 2-ROI design was subsequently introduced to reduce this variability, as the target activity was defined as the relative activity between the two ROIs (e.g., ROI1 – ROI2). This approach offered a more stable signal by normalizing ongoing fluctuations. In our analysis of the early 2-ROI experiments, we observed that animals adopted diverging strategies to achieve threshold crossings. Specifically, some animals increased activity in ROI1 relative to ROI2, while others decreased activity in ROI2 to accomplish the same effect. Once discovered, each animal consistently adhered to its chosen strategy throughout subsequent training sessions. This was an early and intriguing observation, but as the experiments were not originally designed to systematically test this effect, we limited our presentation to the analysis of a small number of animals (shown in Figure 11). We have added details about this observation in our Results section as well, quoted below-

“In the 2-ROI experiment where the task rule required “ROI1 - ROI2” activity to cross a threshold for reward delivery, mice displayed divergent strategies. Some animals predominantly increased ROI1 activity, whereas others reduced ROI2 activity, both approaches leading to successful threshold crossing (Figure 11)”.

We hope this clarifies how the use of two ROIs helps explain the apparent covariation of the signals, and why some divergence from the observations of Clancy et al. (2020) may be expected.

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

Summary:

The study demonstrates the effectiveness of a cost-effective closed-loop feedback system for modulating brain activity and behavior in head-fixed mice. Authors have tested real-time closed-loop feedback system in head-fixed mice two types of graded feedback: 1) Closed-loop neurofeedback (CLNF), where feedback is derived from neuronal activity (calcium imaging), and 2) Closed-loop movement feedback (CLMF), where feedback is based on observed body movement. It is a python based opensource system, and authors call it CLoPy. The authors also claim to provide all software, hardware schematics, and protocols to adapt it to various experimental scenarios. This system is capable and can be adapted for a wide use case scenario.

Authors have shown that their system can control both positive (water drop) and negative reinforcement (buzzer-vibrator). This study also shows that using the close loop system mice have shown better performance, learnt arbitrary task and can adapt to change in the rule as well. By integrating real-time feedback based on cortical GCaMP imaging and behavior tracking authors have provided strong evidence that such closed-loop systems can be instrumental in exploring the dynamic interplay between brain activity and behavior.

Strengths:

Simplicity of feedback systems designed. Simplicity of implementation and potential adoption.

Weaknesses:

Long latencies, due to slow Ca2+ dynamics and slow imaging (15 FPS), may limit the application of the system.

We appreciate the reviewer’s comment and agree that latency is an important factor in our setup. The latency arises partly from the inherent slow kinetics of calcium signaling and GCaMP6s, and partly from the imaging rate of 15 FPS (every 66 ms). These limitations can be addressed in several ways: for example, using faster calcium indicators such as GCaMP8f, or adapting the system to electrophysiological signals, which would require additional processing capacity. In our implementation, image acquisition was fixed at 15 FPS to enable real-time frame processing (256 × 256 resolution) on Raspberry Pi 4B devices. With newer hardware, such as the Raspberry Pi 5, substantially higher acquisition and processing rates are feasible (although we have not yet benchmarked this extensively). More powerful platforms such as Nvidia Jetson or conventional PCs would further support much faster data acquisition and processing.

Major comments:

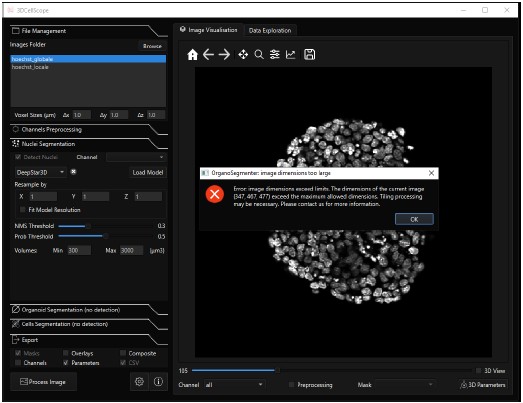

(1) Page 5 paragraph 1: "We tested our CLNF system on Raspberry Pi for its compactness, general-purpose input/output (GPIO) programmability, and wide community support, while the CLMF system was tested on an Nvidia Jetson GPU device." Can these programs and hardware be integrated with windows-based system and a microcontroller (Arduino/ Tency). As for the broad adaptability that's what a lot of labs would already have (please comment/discuss)?

While we tested our CLNF system on a Raspberry Pi (chosen for its compactness, GPIO programmability, and large user community) and our CLMF system on an Nvidia Jetson GPU device (to leverage real-time GPU-based inference), the underlying software is fully written in Python. This design choice makes the system broadly adaptable: it can be run on any device capable of executing Python scripts, including Windows-based PCs, Linux machines, and macOS systems. For hardware integration, we have confirmed that the framework works seamlessly with microcontrollers such as Arduino or Teensy, requiring only minor modifications to the main script to enable sending and receiving of GPIO signals through those boards. In fact, we are already using the same system in an in-house project on a Linux-based PC where an Arduino is connected to the computer to provide GPIO functionality. Furthermore, the system is not limited to Raspberry Pi or Arduino boards; it can be interfaced with any GPIO-capable devices, including those from Adafruit and other microcontroller platforms, depending on what is readily available in individual labs. Since many neuroscience and engineering laboratories already possess such hardware, we believe this design ensures broad accessibility and ease of integration across diverse experimental setups.

(2) Hardware Constraints: The reliance on Raspberry Pi and Nvidia Jetson (is expensive) for real-time processing could introduce latency issues (~63 ms for CLNF and ~67 ms for CLMF). This latency might limit precision for faster or more complex behaviors, which authors should discuss in the discussion section.

In our system, we measured latencies of approximately ~63 ms for CLNF and ~67 ms for CLMF. While such latencies indeed limit applications requiring millisecond precision, such as fast whisker movements, saccades, or fine-reaching kinematics, we emphasize that many relevant behaviors, including postural adjustments, limb movements, locomotion, and sustained cortical state changes, occur on timescales that are well within the capture range of our system. Thus, our platform is appropriate for a range of mesoscale behavioral studies that probably needs to be discussed more. It is also important to note that these latencies are not solely dictated by hardware constraints. A significant component arises from the inherent biological dynamics of the calcium indicator (GCaMP6s) and calcium signaling itself, which introduce slower temporal kinetics independent of processing delays. Newer variants, such as GCaMP8f, offer faster response times and could further reduce effective biological latency in future implementations.

With respect to hardware, we acknowledge that Raspberry Pi provides a low-cost solution but contributes to modest computational delays, while Nvidia Jetson offers faster inference at higher cost. Our choice reflects a balance between accessibility, cost-effectiveness, and performance, making the system deployable in many laboratories. Importantly, the modular and open-source design means the pipeline can readily be adapted to higher-performance GPUs or integrated with electrophysiological recordings, which provide higher temporal resolution. Finally, we agree with the reviewer that the issue of latency highlights deeper and interesting questions regarding the temporal requirements of behavior classification. Specifically, how much data (in time) is required to reliably identify a behavior, and what is the minimum feedback delay necessary to alter neural or behavioral trajectories? These are critical questions for the design of future closed-loop systems and ones that our work helps frame.

We have added a slightly modified version of our response above in the discussion section under “Experimental applications and implications”.

(3) Neurofeedback Specificity: The task focuses on mesoscale imaging and ignores finer spatiotemporal details. Sub-second events might be significant in more nuanced behaviors. Can this be discussed in the discussion section?

This is a great point and we have added the following to the discussion section. “In the case of CLNF we have focused on regional cortical GCAMP signals that are relatively slow in kinetics. While such changes are well suited for transcranial mesoscale imaging assessment, it is possible that cellular 2-photon imaging (Yu et al. 2021) or preparations that employ cleared crystal skulls (Kim et al. 2016) could resolve more localized and higher frequency kinetic signatures.”

(4) The activity over 6s is being averaged to determine if the threshold is being crossed before the reward is delivered. This is a rather long duration of time during which the mice may be exhibiting stereotyped behaviors that may result in the changes in DFF that are being observed. It would be interesting for the authors to compare (if data is available) the behavior of the mice in trials where they successfully crossed the threshold for reward delivery and in those trials where the threshold was not breached. How is this different from spontaneous behavior and behaviors exhibited when they are performing the test with CLNF?

We would like to emphasize that we are not directly averaging activity over 6 s to compare against the reward threshold. Instead, the preceding 6 s of activity is used solely to compute a dynamic baseline for ΔF/F<sub>0</sub> ( ΔF/F<sub>0</sub> = (F –F<sub>0</sub> )/F<sub>0</sub>). Here, F<sub>0</sub>is calculated as the mean fluorescence intensity over the prior 6 s window and is updated continuously throughout the session. This baseline is then subtracted from the instantaneous fluorescence signal to detect relative changes in activity. The reward threshold is therefore evaluated against these baseline-corrected ΔF/F<sub>0</sub> values at the current time point, not against an average over 6 s. This moving-window baseline correction is a standard approach in calcium imaging analyses, as it helps control for slow drifts in signal intensity, bleaching effects, or ongoing fluctuations unrelated to the behavior of interest. Thus, the 6-s window is not introducing a temporal lag in reward assignment but is instead providing a reference to detect rapid increases in cortical activity. We have added the term dynamic baseline to the Methods to clarify.

Recommendations for the authors

Reviewer #1 (Recommendations for the authors):

Additional suggestions for improved or additional experiments, data or analyses.

For: "Looking closely at their reward rate on day 5 (day of rule change), they had a higher reward rate in the second half of the session as compared to the first half, indicating they were adapting to the rule change within one session." It would be helpful to see this data, and would be good to see within-session learning on the rule change day

Thank you for pointing this out. We had missed referencing the figure in the text, and have now added a citation to Supplementary Figure 4A, which shows the cumulative rewards for each day of training. As seen in the plot for day 5, the cumulative rewards are comparable to those on day 1, with most rewards occurring during the second half of the session.

For: "These results suggest that motor learning led to less cortical activation across multiple regions, which may reflect more efficient processing of movement-related activity," it could also be the case that the behaviour became more stereotyped over learning, which would lead to more concentrated, correlated activity. To test this, it would be good to look at the limb variability across sessions. Similarly, if it is movement-related, there should be good decoding of limb kinematics.

Indeed, we observed that behavior became more stereotyped over the course of learning, as shown in Supplementary Figure 4C, 4D. One plausible explanation for the reduction in cortical activation across multiple regions is that behavior itself became more stereotyped, a possibility we have explored in the manuscript. Specifically, forelimb movements during the trial became increasingly correlated as mice improved on the task, particularly in the groups that received auditory feedback (Rule-change and No-rule-change groups; Figure 8). As movements became more correlated, overall body movements during trials decreased and aligned more closely with the task rule (Figure 9D). This suggests that reduced cortical activity may in part reflect changes in behavior. Importantly, however, in the Rule-change group, we observed that on the day of the rule switch (day 5), when the target shifted from the left to the right forelimb, cortical activity increased bilaterally (Figure 9A–C). This finding highlights our central point: groups that received feedback (Rule-change and No-rule-change) were able to identify the task rule more effectively, and both their behavior and cortical activity became more specifically aligned with the rule compared to the No-feedback group. We agree with the reviewers that additional analyses along these lines would be valuable future directions. To facilitate this, we have included the movement data for readers who may wish to pursue further analyses, details can be found under “Data and code availability” in Methods section. However, given the limited sample sizes in our dataset and the need to keep the manuscript focused on the central message, we felt that including these additional analyses here would risk obscuring the main findings.

For: "We believe the decrease in ΔF/F0peak is unlikely to be driven by changes in movement, as movement amplitudes did not decrease significantly during these periods (Figure 7D CLMF Rule-change)." I would formally compare the two conditions. This is an important control. Also, another way to see if the change in deltaF is related to movement would be to see if you can predict movement from the deltaF.

Figure 7D in the previous version is Figure 9D in the current revision of the manuscript. We've assessed this for the examples shown based on graphing the movement data, unfortunately there is not enough of that data to do a group analysis of movement magnitude. We would suggest that this would be an excellent future direction that would take advantage of the flexible open source nature of our tool.

Recommendations for improving the writing and presentation.

In the abstract there is no mention of the rationale for the project, or the resulting significance. I would modify this to increase readership by the behavioral neuroscience community. Similarly, the introduction also doesn't highlight the value of this resource for the field. Again, I think the pyControl paper does a good job of this. For readability, I would add more subheadings earlier in the results, to separate the different technical aspects of the system.

We have revised the introduction to include the rationale for the project, its potential implications, and its relevance for translational research. We have also framed the work within the broader context of the behavioral and systems neuroscience community. We greatly appreciate this suggestion, as we believe it enhances the clarity and accessibility of the manuscript for the community.

For: "While brain activity can be controlled through feedback, other variables such as movements have been less studied, in part because their analysis in real time is more challenging." I would highlight research that has studied the control of behavior through feedback, such as the Mathis paper where mice learn to pull a joystick to a virtual box, and adapt this motion to a force perturbation.

We have added a citation to the Mathis paper and describe this as an additional form of feedback. The text is quoted below:

“Opportunities also exist in extending real time pose classification (Forys et al. 2020; Kane et al. 2020) and movement perturbation (Mathis et al. 2017) to shape aspects of an animal’s motor repertoire.”

Some of the results content would be better suited for the methods, one example: "A previous version of the CLNF system was found to have non-linear audio generation above 10 kHz, partly due to problems in the audio generation library and partly due to the consumer-grade speaker hardware we were employing. This was fixed by switching to the Audiostream (https://github.com/kivy/audiostream) library for audio generation and testing the speakers to make sure they could output the commanded frequencies"

This is now moved to the Methods section.

For: "There are reports of cortical plasticity during motor learning tasks, both at cellular and mesoscopic scales (17-19), supporting the idea that neural efficiency could improve with learning," not sure I agree with this, the studies on cortical plasticity are usually to show a neural basis for the learning observed, efficiency is separate from this.

We have modified this statement to remove the concept of efficiency "There are reports of cortical plasticity during motor learning tasks, both at cellular and mesoscopic scales (17-19).”

The paragraph that opens "Distinct task- and reward-related cortical dynamics" that describes the experiment should appear in the previous section, as the data is introduced there.

We have moved the mentioned paragraphs in the previous section where we presented the data and other experiment details. This makes the text more readable and contextual.

I would present the different ROI rules with better descriptors and visualization to improve the readability.

We have added Supplementary Figure 7, which provides visualizations of the ROIs across all task rules used in the CLNF experiments.

Minor corrections to the text and figures.

Figure 1 is a little crowded, combining the CLNF and CLMF experiments, I would turn this into a 2 panel figure, one for each, similar to how you did figure 2.

We have revised Figure 1 to include two panels, one for CLNF and one for CLMF. The colored components indicate elements specific to each setup, while the uncolored components represent elements shared between CLNF and CLMF. Relevant text in the manuscript is updated to refer to these figures.

For Figure 2, the organization of the CLMF section is not intuitive for the reader. I would reorder it so it has a similar flow as the CLNF experiment.

We have revised the figure by updating the layout of panel B (CLMF) to align with panel A (CLNF), thereby creating a more intuitive and consistent flow between the panels. We appreciate this helpful suggestion, which we believe has substantially improved the clarity of the figure. The corresponding text in the manuscript has also been updated to reflect these changes.

For Figure 3, highlight that C and E are examples. They also seem a little out of place, so they could even be removed.

We have now explicitly labeled Figures 3C and 3E as representative examples (figure legend and on figure itself). We believe including these panels provides helpful context for readers: Figure 3C illustrates how the ROIs align on the dorsal cortical brain map with segmented cortical regions, while Figure 3E shows example paw trajectories in three dimensions, allowing visualization of the movement patterns observed during the trials.

In the plots, I would add sample sizes, for instance, in CLNF learning curve in Figure 4A, how many animals are in each group?

We have labeled Figure 4 with number of animals used in CLNF (No-rule-change, N=23; Rule-change, N=17), and CLMF (Rule-change, N=8; No-rule-change, N=4; No-feedback, N=4).

Also, Figure 7 for example, which figures are single-sessions, versus across animals? For Figure 7c, what time bin is the data taken from?

We have clarified this now and mentioned it in all the figures. Figure 7 in the previous version is Figure 9 in the current updated manuscript. Figure 9A is from individual sessions on different days from the same mouse. Figure 9B is the group average reward centered ΔF/F<sub>0</sub> activity in different cortical regions (Rule-change, N=8; No-rule-change, N=4; No-feedback, N=4). Figure 9C shows average ΔF/F<sub>0</sub> peak values obtained within -1sec to +1sec centered around the reward point (N=8).

It says "punish" in Figure 3, but there is no punishment?

Yes, the task did not involve punishment. Each trial resulted in either a success, which is followed by a reward, or a failure, which is followed by a buzzer sound. To better reflect these outcomes, we have updated Figure 3 and replaced the labels “Reward” with “Success” and “Punish” with “Failure.”

The regression on 5c doesn't look quite right, also this panel is not mentioned in the text.

The figure referred to by the reviewer as Figure 5 is now presented as Figure 6 in the revised manuscript. Regarding the reviewer’s observation about the regression line in the left panel of Figure 5C, the apparent misalignment arises because the majority of the data points are densely clustered at the center of the scatter plot, where they overlap substantially. The regression line accurately reflects this concentration of overlapping data. To improve clarity, we have updated the figure and ensured that it is now appropriately referenced in the Results section.

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations for the authors):

(1) There would be many interesting observations and links between the peripheral and cortical studies if there was a body video available during the cortical study. Is there any such data available?

We agree that a detailed analysis of behavior during the CLNF task would be necessary to explore any behavior correlates with success in the task. Unfortunately, we do not have a sufficient video of the whole body to perform such an analysis.

(2) The text (p. 24) states: [intracortical GCAMP transients measured over days became more stereotyped in kinetics and were more correlated (to each other) as the task performance increased over the sessions (Figure 7E).] But I cannot find this quantification in the figures or text?

Figure 7 in the previous version of the manuscript now appears as Figure 9. In this figure, we present cortical activity across selected regions during trials, and in Figure 9E we highlight that this activity becomes more correlated. Since we did not formally quantify variability, we have removed the previous claim that the activity became stereotyped and revised the text in the updated manuscript accordingly.

Typos:

10-serest c (page 13)

Inverted color codes in figure 4E vs F

Reviewer #3 (Recommendations for the authors):

We have mostly attempted to limit the feedback to suggestions and posed a few questions that might be interesting to explore given the dataset the authors have collected.

Comments:

In close loop systems the latency is primary concern, and authors have successfully tested the latency of the system (Delay): from detection of an event to the reaction time was less than 67ms.

We have commented on the issues and limitations caused by latency, and potential future directions to overcome these challenges in responses to some of the previous comments.

Additional major comments:

"In general, all ROIs assessed that encompassed sensory, pre-motor, and motor areas were capable of supporting increased reward rates over time (Figure 4A, Animation 1)." Fig 4A is merely showing change in task performance over time and does not have information regarding the changes observed specific to CLNF for each ROI.

We acknowledge that the sample size for individual ROI rules was not sufficient for meaningful comparisons. To address this limitation, we pooled the data across all the rules tested. The manuscript includes a detailed list of the rules along with their corresponding sample sizes for transparency.

A ΔF/F<sub>0</sub> threshold value was calculated from a baseline session on day 0 that would have allowed 25% performance. Starting from this basal performance of around 25% on day 1, mice (CLNF No-rule-change, n=28 and CLNF Rule-change, n=13). It is unclear what the replicates here are. Trials or mice? The corresponding Figure legend has a much smaller n value.

Thank you for pointing this out. We realized that we had not indicated the sample replicates in the figure, and the use of n instead of N for the number of animals may have been misleading. We have now corrected the notation and clarified this information in the figure to resolve the discrepancy.

What were the replicates for each ROI pairs evaluated?

Each ROI rule and number of mice and trials are listed in Table 5 and Table 6.

Our analysis revealed that certain ROI rules (see description in methods) lead to a greater increase in success rate over time than others (Supplementary Figure 3D). The Supplementary figures 3C and 3D are blurry and could use higher resolution images.

We have increased the font size of the text that was previously difficult to read and re-exported the figure at a higher resolution (300 DPI). We believe these changes will resolve the issue.

Also, It will help the reader is a visual representation of the ROI pairs are provided, instead of the text view. One interesting question is whether there are anatomical biases to fast vs slow learning pairs (Directionality - anterior/posterior, distance between the selected ROIs etc). This could be interesting to tease apart.

We have added Supplementary Figure 7, which provides visualizations of the ROIs across all task rules used in the CLNF experiments. While a detailed investigation of the anatomical basis of fast versus slow learning cortical ROIs is beyond the scope of the present study, we agree that this represents an exciting future direction for further research.

How distant should the ROIs be to achieve increased task performance?

We appreciate this insightful question. We did not specifically test this scenario. In our study, we selected 0.3 × 0.3 mm ROIs centered on the standard AIBS mouse brain atlas (CCF). At this resolution, ROIs do not overlap, regardless of their placement in a two-ROI experiment. Furthermore, because our threshold calculations are based on baseline recordings, we expect the system would function for any combination of ROI placements. Nonetheless, exploring this systematically would be an interesting avenue for future experiments.

Figures:

I would leave out some of the methodological details such as the protocol for water restriction (Fig. 3) out of the legend. This will help with readability.

We have removed some of the methodological details, including those mentioned above, from the legend of Figure 3 in the updated manuscript.

Fig 1 and Fig 2: In my opinion, It would be easier for the reader if the current Fig. 2, which provides a high level description of CLNF and CLBF is presented as Fig. 1. The current Fig. 1, goes into a lot of methodological implementation details, and also includes a lot of programming jargon that is being introduced early in the paper that is hard to digest early on in the paper's narrative.

Thank you for the suggestion. In the new manuscript, Figure 1 and Figure 2 have been swapped.

Higher-resolution images/ plots are needed in many instances. Unsure if this is the pdf compression done by the manuscript portal that is causing this.

All figures were prepared in vector graphics format using the open-source software Inkscape. For this manuscript, we exported the images at 300 DPI, which is generally sufficient for publication-quality documents. The submission portal may apply additional processing, which could have resulted in a reduction in image quality. We will carefully review the final submission files and ensure that all figures are clear and of high quality.

The authors repeatedly show ROI specific analysis M1_L, F1_R etc. It will be helpful to provide a key, even if redundant in all figures to help the reader.

We have now included keys to all such abbreviations in all the figures.

There are also instances of editorialization and interpretation e.g., "Surprisingly, the "Rule-change" mice were able to discover the change in rule and started performing above 70% within a day of the rule change, on day 6" that would be more appropriate in the main body of the paper.

Thank you for pointing this out in the figure legend, and we have removed it now since we already discussed this in the Results.

Minor comments

(1) The description of Figure 1 is hard to follow and can be described better based on how the information is processed and executed in the system from source to processing and back. Using separated colors (instead of shaded of grey) for the neuro feedback and movement feedback would help as well. Common components could have a different color. The specification like the description of the config file should come later.

Figure 1 in the previous version is Figure 2 in the updated version. We have taken suggestions from other reviewers and made the figure easier to understand and split it into two panels with color coding Green for CLNF, Pink for CLMF specific parts while common shared parts are left without any color.

(2) Page 20 last paragraph:

Authors are neglecting that the rule change is done one day prior and the results that you see in the second half on the 6th day are not just because of the first half of the 6th day instead combined training on the 5th day (rule change) and then the first half of the 6th day. Rephrasing this observation is essential.

We have revised the text for clarity to indicate that the performance increase observed on day 6 is not necessarily attributable to training on that day. In fact, we noted and mentioned that mice began to perform the task better during the second half of the session on day 5 itself.

(3) The method section description of the CLMF setup (Page no 39 first paragraph) is more detailed, a diagram of this setup would make it easy to follow and a better read.

We have made changes to the CLMF setup (Figure 1B) and CLMF schematic (Figure 2B) to make it easier to understand parts of the setup and flow of control.