Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

This study investigates the molecular mechanism by which warm temperature induces female-to-male sex reversal in the ricefield eel (Monopterus albus), a protogynous hermaphroditic fish of significant aquacultural value in China. The study identifies Trpv4 - a temperature-sensitive Ca<sup>2+</sup> channel - as a putative thermosensor linking environmental temperature to sex determination. The authors propose that Trpv4 causes Ca<sup>2+</sup> influx, leading to activation of Stat3 (pStat3).pStat3 then transcriptionally upregulates the histone demethylase Kdm6b (aka Jmjd3), leading to increased dmrt1 gene expression and ovo-testes development. This work aims to bridge ecological cues with molecular and epigenetic regulators of sex change and has potential implications for sex control in aquaculture.

Strengths:

(1) This study proposes the first mechanistic pathway linking thermal cues to natural sex reversal in adult ricefield eel, extending the temperature-dependent sex determination paradigm beyond embryonic reptiles and saltwater fish.

(2) The findings could have applications for aquaculture, where skewed sex ratios apparently limit breeding efficiency.

We thank you for the encouraging comments of our work, and answering your questions has greatly improved the quality of the manuscript.

Weaknesses:

(A) Scientific Concerns:

(1) There is insufficient replication and data transparency. First, the qPCR data are presented as bar graphs without individual data points, making it impossible to assess variability or replication. Please show all individual data points and clarify n (sample size) per group. Second, the Western blotting is only shown as single replicates. If repeated 2-3 times as stated, quantification and normalization (e.g., pStat3/Stat3, GAPDH loading control) are essential. The full, uncropped blots should be included in the supplementary data.

We thank you for the critical comments. Now we have remade the bar graphs with individual data points, and added the sample size per group if possible. Quantification and/or normalization of the WB data based on at least two replicates were included. The representative uncropped blots have also been loaded as the supplementary data.

(2) The biological significance of the results is not clear. Many reported fold changes (e.g., kdm6b modulation by Stat3 inhibition, sox9a in S3A) are modest (<2-fold), raising concerns about biological relevance. Can the authors define thresholds of functional relevance or confirm phenotypic outcomes in these animals?

We thank you for the inspiring comments. Most of the experiments were transient in nature, for instance, warm temperature treatment of fish for 3-4 days, the fold change of gene expression were modest.

We admit that there are some shortcomings in this work. The major one is lacking of data showing that Trpv4 inhibition/activation,or pStat3 inhibition/activation can cause a gonadal phenotype change, for instance, from ovary to ovotestis or causing females to intersex fish. We only showed that pharmacological or RNAi can lead to change in sex-biased gene expression or affect temperature-induced gene expression, but not gonadal transformation.

In natural population, the sex change of ricefield eel may take several months to one year or even longer. We propose that the magnitude and duration of temperature exposure promote sex change of ricefield eel by driving the accumulation of testicular differentiation genes in sufficient quantities. In experimental condition, to realize the gonadal phenotype change, animals may need to be under repeated pharmaceutical treatment (3 day interval treatment) for longer time to reach a threshold. However, long term treatment significantly increases the death rate of the animals, caused by stress or frequent manipulation.

Inspired by your comment, we are optimizing the experimental conditions in order to cause some phenotypic outcomes, thanks.

(3) The specificity of key antibodies is not validated. Key antibodies (Stat3, pStat3, Foxl2, Amh) were raised against mammalian proteins. Their specificity for ricefield eel proteins is unverified. Validation should include siRNA-mediated knockdown with immunoblot quantification with 3 replicates. Homemade antibodies (Sox9a, Dmrt1) also require rigorous validation.

We thank you for the comments about the specificity of the antibodies. First,when choosing the commercial antibodies, we have compared the immunogen of the animal with the corresponding amino acids of ricefield eel, making sure that it was conserved to some extent (at least> 85% similarity). Second, we have referred the published work, where the antibodies have been proven to work in zebrafish, frogs, and turtles et al. This was true for pStat3 and Stat3 antibodies (Weber et al. 2020; Ge et al., 2024). Third, the specificity for each antibody was assessed using WB, based on the predicted size of the protein and the correct control setting.

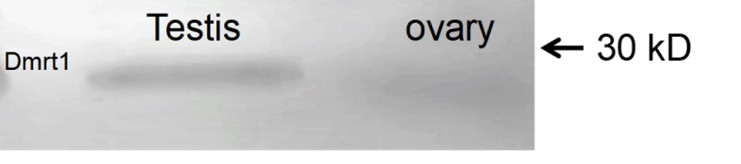

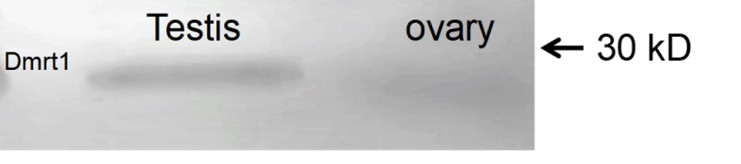

For instance, we are very confident for the specificity for Dmrt1 antibody. First, Dmrt1 protein was readily detected in testes of males but barely detected in ovaries of females (Author response image 1). Second, Dmrt1 protein was not detected in ovary of fish at cool temperature, but clearly detected in nuclei of follicles in warm temperature-treated fish (Figure 3C, 4B), in line with our qPCR results. Third, by performing IF, Dmrt1 was not detected in females reared at lower temperature. By contrast, after warm temperature treatment or Trpv4 activation, it was detected in the nuclei in specific cell types but not everywhere (Figure 3E, 6C).

Author response image 1.

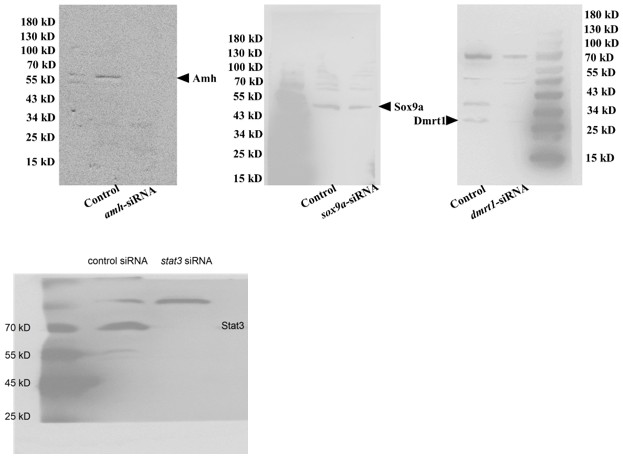

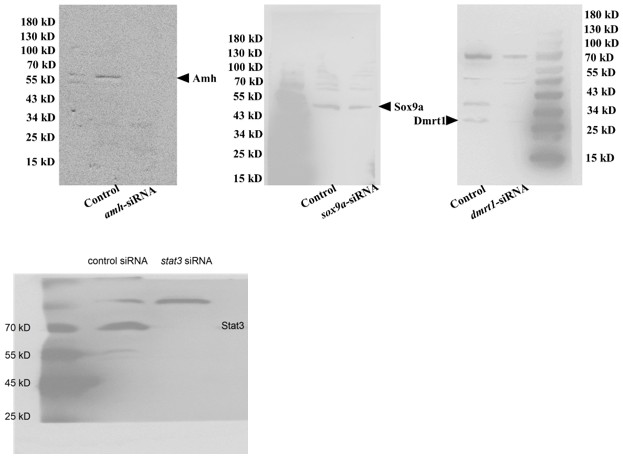

Although we have carefully evaluated the antibodies before experiments as described above, in response to your concerns, we went on to validate Amh, Dmrt1, Sox9a, and Stat3 antibodies using the corresponding siRNAs (Author response image 2). The results indicated that the antibodies, although not perfect, can be used in this work, as the expected band was gone or reduced in intensity. The experiments were repeated two times, and shown were representative.

Author response image 2.

(4) Most of the imaging data (immunofluorescence) is inconclusive. Immunofluorescence panels are small and lack monochrome channels, which severely limits interpretability. Larger, better-contrasted images (showing the merge and the monochrome of important channels) and quantification would enhance the clarity of these findings.

We apologize for the poor quality of the IF images. At your suggestion, we have repeated the majority of the IF experiments, and imaging data with better quality were presented in the revised manuscript. Quantification of WB and IF was also included to enhance the clarity. Please see the revised manuscript, Thanks.

(B) Other comments about the science:

(1) In S3A, sox9a expression is not dose-responsive to Trpv4 modulation, weakening the causal inference.

We have repeated the experiments, and new data was included for the replacement of the old one in the revised manuscript.

(2) An antibody against Kdm6b (if available) should be used to confirm protein-level changes.

We thank you for the nice suggestion. Unfortunately, current commercial antibody for Kdm6b is for mammals, which was not working in ricefield eel. At your suggestion, we are going to make one in future.

In sum, the interpretations are limited by the above concerns regarding data presentation and reagent specificity.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

This study presents valuable findings on the molecular mechanisms driving the female-to-male transformation in the ricefield eel (Monopterus albus) during aging. The authors explore the role of temperature-activated TRPV4 signaling in promoting testicular differentiation, proposing a TRPV4-Ca<sup>2+</sup>-pSTAT3-Kdm6b axis that facilitates this gonadal shift.

We thank you for the encouraging comments. Answering your questions has greatly improved our understanding of Trpv4 function in ricefield eel, and the quality of the manuscript.

Strengths:

The manuscript describes an interesting mechanism potentially underlying sex differentiation in M. albus.

Weaknesses:

The current data are insufficient to fully support the central claims, and the study would benefit from more rigorous experimental approaches.

(1) Overstated Title and Claims:

The title "TRPV4 mediates temperature-induced sex change" overstates the evidence. No histological confirmation of gonadal transformation (e.g., formation of testicular structures) is presented. Conclusions are based solely on molecular markers such as dmrt1 and sox9a, which, although suggestive, are not definitive indicators of functional sex reversal.

We thank you for pointing out this. The title has been changed to “Trpv4 links environmental temperature to testicular differentiation in hermaphroditic ricefield eel.”

(2) Temperature vs Growth Rate Confounding (Figure 1E):<br />

The conclusion that warm temperature directly induces gonadal transformation is confounded by potential growth rate effects. The authors state that body size was "comparable" between 25C and 33C groups, but fail to provide supporting data. In ectotherms, growth is intrinsically temperature-dependent. Given the known correlation between size and sex change in M. albus, growth rate-rather than temperature per se-may underlie the observed sex ratio shifts. Controlled growth-matched comparisons or inclusion of growth rate metrics are needed.

We thank you for the critical comments. We have repeated the experiments, and have carefully compared the body length and weight, and results showed that there is no big difference between 25 and 33 degree groups. Please see Figure S1D-E, and the text in the last paragraph of “Warm temperature promotes gonadal transformation” section in the Results part.

(3) TRPV4 as a Thermosensor-Insufficient Evidence:<br />

The characterisation of TRPV4 as a direct thermosensor lacks biophysical validation. The observed transcriptional upregulation of Trpv4 under heat (Figure 2) reflects downstream responses rather than primary sensor function. Functional thermosensors, including TRPV4, respond to heat via immediate ion channel activity-typically measurable within seconds-not mRNA expression over hours. No patch-clamp or electrophysiological data are provided to confirm TRPV4 activation thresholds in eel gonadal cells.

We thank you for the critical comments. The patch-clamp or electrophysiological experiments require special equipment and well-trained expert, unfortunately, our lab members and nearby collaborators have no experience in performing the kind of experiments. The Trpv4 is a well-known cation channel protein that is activated by moderate heat (> 27 degree). And a body of published work has demonstrated its role in the regulation of Ca<sup>2+</sup> signals via change its configuration in response to temperature (J Physiol. 2017 Oct 25;595(22):6869–6885. doi: 10.1113/JP275052; Cell Death Dis 11, 1009 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-020-03181-7; Cell Death Dis 10, 497 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-019-1708-9; Cell calcium, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceca.2026.103108).

Consistently, warm temperature increased calcium influx within an hour, similar to the Trpv4 agonist treatment (Figure 2E, 5D), and addition of ion channel Trpv4 inhibitor prevents the calcium signals by war temperature treatment. Moreover, calcium signaling activity is closely linked with pStat3 activity and expression of sex-biased genes (Figures 5G, 6F). Although we did not show biophysical data, these results implied that Trpv4 is a thermosensor, and regulate the downstream pathway via the regulation of calcium signals, in line with it functions as an ion channel.

Additionally, the Ca<sup>2+</sup> imaging assay (Figure 2F) lacks essential details: the timing of GSK1016790A/RN1734 administration relative to imaging is unclear, making it difficult to distinguish direct channel activity from indirect transcriptional effects.

We have added more information for Ca<sup>2+</sup> imaging assay (now Figure 2E and the corresponding text in Figure 2 legend, in the revised manuscript). In particular, we added the timing of treatment to better show that it was a direct effect.

(4) Cellular Context of TRPV4 Activity Is Unclear:<br />

In situ hybridisation suggests TRPV4 expression shifts from interstitial to somatic domains under heat (Figures. 2H, S2C), implying potential cell-type-specific roles. However, the study does not clarify: (i) whether TRPV4 plays the same role across these cell types, (ii) why somatic cells show stronger signal amplification, or (iii) the cellular composition of explants used in in vitro assays. Without this resolution, conclusions from pharmacological manipulation (e.g., GSK1016790A effects) cannot be definitively linked to specific cell populations.

We thank you for the inspiring comments. We have performed IF experiments using Trpv4 specific antibodies (antibody specificity was confirmed). It was clearly shown that Trpv4 was expressed in a portion of follicle cells. To explore the identity of Trpv4-expressing somatic cells, we have performed double IF experiments using Trpv4 and Foxl2, a granulosa cell marker. The results (Figure 2H) clearly showed that Trpv4-expressing cells are a portion of Foxl2-positive granulosa cells. We propose that Trpv4-expressing granulosa cells may play an important role in sensing the temperature, and that Trpv4-expressing granulosa cells transdifferentiate into Sertoli cells by warm temperature exposure, because Dmrt1, a Sertoli cell marker, started within follicles in a typical granulosa cell location. Unfortunately, current Dmrt1/Trpv4 antibodies are both produced from rabbit. To overcome this, we are ordering mouse Dmrt1 antibodies, and in future we will perform Trpv4/Dmrt1 double IF to show if Dmrt1 positive cells co-localize with Trpv4 expressing cells. We would like to update the results to you once the antibody was available.

As our animal experiments (Figure 2H) have clearly shown the identify of Trpv4 expressing somatic cells, we did not repeat the experiments using explants, to explore the cellular composition of explants used in in vitro assays.

(5) Rapid Trpv4 mRNA Elevation and Channel Function:<br />

The authors report a dramatic increase in Trpv4 mRNA within one day of heat exposure (Figures 4D, S2B). Given that TRPV4 is a membrane channel, not a transcription factor, its rapid transcriptional sensitivity to temperature raises mechanistic questions. This finding, while intriguing, seems more correlational than functional. A clearer explanation of how TRPV4 senses temperature at the molecular level is needed.

We appreciate you for your inspiring comments. Actually, we are also wondering about how trpv4 mRNA was regulated by warm temperature. First of all, the up-regulation of trpv4 mRNA is true, as evidenced by multiple pieces of data using qPCR and ISH experiments. It appears that ovarian cells respond to the temperature changes by increasing calcium influx via Trpv4 ion channel,as well as by increasing trpv4 mRNA expression levels.

Then, how trpv4 mRNA is regulated by heat? It is well-known that gene expression can be regulated by subtle temperature change via some direct temperature sensing genes (Haltenhof et al., 2020). We hypothesized that trpv4 is a downstream target of these thermosensors, displaying a mechanism similar to mammals. Actually, we have performed some experiments, and the preliminary data were obtained, which support our hypothesis.

Because the mechanistic explanation study is undergoing and not published, we chose not to discuss it in detail in the revised manuscript. We wish to report it by the end of this year, and by then are pleased to update you with the progress.

(6) Inconclusive Evidence for the Ca<sup>2+</sup>-pSTAT3-Kdm6b Axis: Although the authors propose a TRPV4-Ca<sup>2+</sup>-pSTAT3-Kdm6b-dmrt1 pathway, intermediate steps remain poorly supported. For example, western blot data (Figures 3C, 4B) do not convincingly demonstrate significant pSTAT3 elevation at 34C. Higher-resolution and properly quantified blots are essential. The inferred signalling cascade is based largely on temporal correlation and pharmacological inhibition, which are insufficient to establish direct regulatory relationships.

We thank you for the critical comments. In response to your concerns, we have repeated experiments, and better resolution WB data with proper quantification were included in the revised manuscript. In particular, we convincingly demonstrate that 34 degree caused significant pStat3 elevation.

To directly establish regulatory relationship of the members, at your suggestion, we provided some genetic and molecular biology data to support our conclusion in the revised manuscript. For instance, we have knockdown the stat3 gene by using siRNAs, and as shown in Figure 6F, we further showed that pStat3 is functionally downstream of Trpv4. Moreover, ChIP and luciferase assays were performed to show that pStat3 directly binds and activate kdm6b (Figure 7B-C). We have also performed various pharmacological inhibition to further strength our conclusion (Figures 6B-E).

(7) Species-Specific STAT3-Kdm6b Regulation Is Unresolved:<br />

The proposed activation of Kdm6b by pSTAT3 contrasts with findings in the red-eared slider turtle (Trachemys scripta), where pSTAT3 represses Kdm6b. This divergence in regulatory direction between the two TSD species is surprising and demands further justification. Cross-species differences in binding motifs or epigenetic context should be explored. Additional evidence, such as luciferase reporter assays (using wild-type and mutant pSTAT3 binding motifs in the Kdm6b promoter) is needed to confirm direct activation.

We thank you for the inspiring comments. At your suggestion, we have performed luciferase assay using kdm6b promotor that is intact or mutated. The results were in favor of our statement. Please see Figure 7C and the related text.

A rescue experiment-testing whether Kdm6b overexpression can compensate for pSTAT3 inhibition-would also greatly strengthen the model.

We thank you for the nice suggestion. It is technically challenging to perform kdm6b overexpression or any Kdm6b gain of function experiments (we have tried to make lentivirus, however, it was not working). There is no Kdm6b-specific agonists.

Inspired by you, we are establishing constitutive kdm6b transgenic ricefield eel. Although it require at least a year to allow the fish to grow up for functional experiments, once it was established, we can directly answer some important questions.

(8) Immunofluorescence-Lack of Structural Markers: <br />

All immunofluorescence images should include structural markers to delineate gonadal boundaries. Furthermore, image descriptions in the figure legends and main text lack detail and should be significantly expanded for clarity.

We thank you for the critical comments. At your comments, we have first performed IF using beta-catenin as structural marker. However, the results were not good for some unknown reasons. Then, we used Vimentin as a structural maker, as it can label all the cells in gonads. Foxl2 was used as granulosa cell marker. Dmrt1 was used as Sertoli cell marker.

Some essential description was added in the figure legend as requested. Please see detail in the revised manuscript.

(9) Pharmacological Reagents-Mechanisms and References: <br />

The manuscript lacks proper references and mechanistic descriptions for the pharmacological agents used (e.g., GSK1016790A, RN1734, Stattic). Established literature on their specificity and usage context should be cited to support their application and interpretation in this study.

These pharmacological agents have been used by others (Ge et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2021; Weber et al., 2020; Wu et al.,2024), and they are properly cited in the manuscript.

(10) Efficiency of Experimental Interventions: <br />

The percentage of gonads exhibiting sex reversal following pharmacological or RNAi treatments should be reported in the Results. This is critical for evaluating the strength and reproducibility of the interventions.

We thank you for the critical and important comments. Actually another reviewer has asked the same question. We admit that this was the big shortcoming of the work, as we did not provide data demonstrating that Trpv4 inhibition/activation, or pStat3 inhibition/activation can cause a gonadal phenotype change, for instance, from ovary to ovotestis or causing sex reversal of fish. We only showed that pharmacological or RNAi can lead to alteration of sex-biased gene expression or affect temperature induced gene expression.

In wild population, the entire sex change of ricefield eel may take months to one year or even longer. We propose that the magnitude and duration of temperature exposure promote sex change of ricefield eel by driving the accumulation of testicular differentiation genes in sufficient quantities. In experimental condition, to realize the gonadal phenotype change, animals may need to be under repeated pharmaceutical treatment (3 day interval treatment) for longer time to reach a threshold, however, long term treatment significantly increases the death rate of the animals, caused by stress or frequent manipulation. Actually, my students have tried the experiments, unfortunately, either the number of sex-versing animals were small or the experiments lacked of repeat. So no percentage of gonadal transformation after treatment can be provided at this time, but we have indicated the number of samples when performing molecular experiments (showing expression of sex-biased genes).

Inspired by your important comment, we are optimizing the experimental conditions in order to cause some phenotypic outcomes. By then, the percentage of gonads exhibiting sex reversal following pharmacological or RNAi treatments can be calculated, showing the biological significance.

Recommendations for the authors:

Reviewer #1 (Recommendations for the authors):

Editorial Concerns:

(1) The term "sex reversal" should be clearly defined upfront as female-to-male, and the developmental consequences (e.g., increase in body size post-transition) should be explicitly stated early in the introduction.

We thank our editorial for pointing out this. We have added those in the introduction Part. It reads “The species begins life as a female and then develops into a male through an intersex stage, thus displaying a female-to-male sex reversal during aging. Females are small in size (< 25 cm), and during and after sex change, there is a gradual increase in body size (> 55 cm for the majority of males).”

Additional information was shown in the first and second paragraph in the results Part.

(2) The manuscript references skewed sex ratios in cultured ricefield eel but fails to specify the direction (e.g., too many males or females). This should be clarified to contextualize the biological and commercial problem.

According to your suggestion, we now added additional information, and it reads “The reproductive mode of ricefield eel, which leads to much more females than males in spawning season, severely affects the sex ratio, and decreases the productivity of broodstock. Moreover, adult females lay limited eggs (~200) due to its small size.”

(3) Define TSD (temperature-dependent sex determination) upon first use, not at the second mention.

We have checked this, and make sure it was properly done.

(4) The phrase "quality fries for aquaculture" should be reworded or defined; it is unclear to non-specialists.

We thank you for pointing out this. Now it reads “adult females lay limited eggs (~200) due to its small size, which is a limiting factor for massive production of seedling for aquaculture industry”.

(5) Several in-text citations (e.g., Weber 2020, Wu 2024) are absent from the bibliography. ]

We have double checked the reference, thanks.

(6) The inclusion of page and line numbers would facilitate peer review.

We have now shown the page and line.

(7) The discussion is written vaguely. Clarify species names when discussing comparative biology and consider breaking down complex sentences to aid comprehension for a broad audience, such as that of eLife.

We have added the species name, and try our best to use concise expression. Thanks.