- Sep 2020

-

www.thelancet.com www.thelancet.com

-

Chatterjee, Patralekha. ‘Is India Missing COVID-19 Deaths?’ The Lancet 396, no. 10252 (5 September 2020): 657. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31857-2.

-

- Aug 2020

-

jasp-stats.org jasp-stats.org

-

Introducing JASP 0.11: The Machine Learning Module. (2019, September 24). JASP - Free and User-Friendly Statistical Software. https://jasp-stats.org/2019/09/24/introducing-jasp-0-11-the-machine-learning-module/

-

- Jul 2020

-

dl.acm.org dl.acm.org

-

Panda, A., Gonawela, A., Acharyya, S., Mishra, D., Mohapatra, M., Chandrasekaran, R., & Pal, J. (2020). NivaDuck—A Scalable Pipeline to Build a Database of Political Twitter Handles for India and the United States. International Conference on Social Media and Society, 200–209. https://doi.org/10.1145/3400806.3400830

-

- Jun 2020

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

-

-

The lumper–splitter problem occurs when there is the desire to create classifications and assign examples to them, for example schools of literature, biological taxa and so on.

-

their critics say that if a carnivore is neither a dog nor a bear, they call it a cat

-

-

americanethnologist.org americanethnologist.org

-

Good Vibes: The Complex Work of Social Media Influencers in a Pandemic. (n.d.). American Ethnological Society. Retrieved May 31, 2020, from https://americanethnologist.org/features/pandemic-diaries/pandemic-diaries-affect-and-crisis/good-vibes-the-complex-work-of-social-media-influencers-in-a-pandemic

Tags

- classification

- is:news

- work

- essential worker

- influencer

- COVID-19

- social media

- follower

- lockdown

- staff

- lang:en

Annotators

URL

-

-

socialsciences.nature.com socialsciences.nature.com

-

Research, B. and S. S. at N. (2020, May 23). Standards for evidence in policy decision-making. Behavioural and Social Sciences at Nature Research. http://socialsciences.nature.com/users/399005-kai-ruggeri/posts/standards-for-evidence-in-policy-decision-making

-

-

www.archives.ulaval.ca www.archives.ulaval.ca

- May 2020

-

psyarxiv.com psyarxiv.com

-

Donnellan, E., Sumeyye, Fastrich, G. M., & Murayama, K. (2020). How are Curiosity and Interest Different? Naïve Bayes Classification of People’s Naïve Belief. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/697gk

-

-

arxiv.org arxiv.org

-

Qian, Y., Expert, P., Panzarasa, P., & Barahona, M. (2020). Geometric graphs from data to aid classification tasks with graph convolutional networks. ArXiv:2005.04081 [Physics, Stat]. http://arxiv.org/abs/2005.04081

-

-

psyarxiv.com psyarxiv.com

-

Fenton, N., Hitman, G. A., Neil, M., Osman, M., & McLachlan, S. (2020). Causal explanations, error rates, and human judgment biases missing from the COVID-19 narrative and statistics [Preprint]. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/p39a4

-

- Apr 2020

-

www.iubenda.com www.iubenda.com

-

purposes are grouped into 5 categories (strictly necessary, basic interactions & functionalities, experience enhancement, measurement, targeting & advertising)

-

- Feb 2020

-

-

Orthocoronavirinae

A subfamily of Coronaviridae. Coronaviridae is a family of RNA Viruses within the sub order of Cornidovirineae, which is a sub-order of Nidovirales. Nidovirales is a order of RNA viruses that use animals as hosts.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

- Nov 2019

-

github.com github.com

-

mixed-state checkbox

I guess technically what I've been calling tri-state should be more generically called mixed-state? But I have so far not seen that term used anywhere else. Even web standard, https://www.w3.org/TR/wai-aria-practices-1.1/#checkbox, mentions tri-state but not "mixed-state".

-

- Apr 2019

-

assayjournal.wordpress.com assayjournal.wordpress.com

- Mar 2019

-

arxiv.org arxiv.org

-

A Comparative Study of Neural Network Models for Sentence Classification

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.ijcai.org www.ijcai.org

-

Differentiated Attentive Representation Learning for Sentence Classification

-

- Feb 2019

-

arxiv.org arxiv.org

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

arxiv.org arxiv.org

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

gitee.com gitee.com

-

Text Understanding from Scratch

-

-

gitee.com gitee.com

-

Understanding Short Texts∗

-

-

gitee.com gitee.com

-

static1.squarespace.com static1.squarespace.com

-

strume11ts

New apparatuses with which to see and understand the world differently than did the Ancients.

The connection to Barad becomes even more apparent below when Vico calls "critique" an instrument.

Another instrument that Vico uses/alludes to is the act of classification ("set up a distinction," "the orderly reduction of systematic rules").

-

-

dougengelbart.org dougengelbart.org

-

the conditioning needed by the human being to bring his skills in using Means 1, 2, and 3 to the point where they are operationally effective.

Always interesting to read how Engelbart builds organizational schemes which build off of themselves, very very meta

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

- Jan 2019

-

static1.squarespace.com static1.squarespace.com

-

labelled

Again with labels and names

-

chains of operations thatlink humans, things, media and even animals

Cf. Muckelbauer and Hawhee's discussion, where "humans, animals, and machines [are linked] so intimately that it makes very little sense to attempt to distinguish among these three categories" (767)

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

static1.squarespace.com static1.squarespace.com

-

convergence of virtuality/actuality and human/machine,

The need to categorize collides with situations where the lines are blurred, where categories abut or merge.

-

humans, animals, and machines so intimately that it makesvery little sense to attempt to distinguish among these three categories

There persists a need to categorize, classify, divide, arrange...

This need was mentioned in the NOVA documentary, where people so often wish to fit findings into neat little categories only to find that there are often overlaps that muddy the water (or 'braided stream', if you prefer).

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

signifies a new epistemology insofar as it portraysevents as discrete and isolated; knowledges as mod-ifiable, categorizable, and abstractable; and locally-situated knowledges as best understood by thoseworking remotely

Evokes complexity of creating classifications and boundary objects that can provide relational data, e.g., report of fire and report of car bombing.

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

. Previously, scholars have generally ignored any notion of time. Now, we need to make explicit our use of time in understanding disaster. Such an application, I believe, will give us a much deeper understanding on defining disaster, how and why such events unfold, and how various social entities attempt to return to normal after the event. Finally, the use of social time in disaster can provide sociologists a deeper look into understanding key theoretical issues related to social order, social change and social emergence, along with voluntaristic versus deterministic patterns of behavior among various units of analysis.

Scarcity of temporal considerations in previous work.

Connects sociotemporal experiences and enactment of time to social order, social change, volunteer behavior and new units of analysis.

Here's my central thesis.

-

the field. Such a fresh approach possibly improves a wide range of conceptual issues in disasters and hazards. In addition, such an approach would give us insights on how disaster managers, emergency responders, and disaster victims (recognizing that these “roles” may overlap in some cases) see, use and experience time. This, in turn, could assist with a number of applied issues (e.g., warning, effective “response,” priorities in “recovery”) throughout the process of disaster.

Neal cites his 1997 paper about the need to develop better categories to describe disaster phases. Here, her attempts to work through those classifications with a sociotemporal bent.

Evokes Bowker and Star's work on classification and boundary objects/infrastructures but also Yakura (2002) on temporal boundary objects.

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

The use of disaster periods provides a useful heuristic device for disaster researchers and disaster managers. These various approaches of disaster Phases give researchers an important means to develop research, organize dates, and generate research findings. Similarly, the use of disaster phases benefits disaster managers in attempting to improve their capabilities. Yet, the current use of disaster phases creates broad definitional problems of the field. I show that the current attempts to describe disaster phases are good heuristic devices, but not effective scientific concepts. Yet, scientific, empirical, and theoretical conclusions are drawn from the use of these Phases.

Future work in disaster response research (circa 1997). Primary focus for Neal is:

1) theory development

2) "more systematic, scientific approach to describe disaster phases"

-

The next logical step to aid analysis would be to cross-tabulate the temporal periods of "before, during, and after" with functional activities. This type of analysis and consideration could be further extended by including both the unit of analysis and various social categories such as social class or ethnicity. This type of three-dimensional approach would also strongly highlight the idea that disaster phases are multilayered. Overall, not only do different groups and units of analysis experience the phases at different times, but that multiple aspects of time (i.e., objective and subjective; before, during, after a disaster) intermesh with specific activities.

Evokes temporal boundary objects and classification alongside feminist and post-colonial HCI approaches.

-

We must differentiate whether the use of any phrase refers to temporal or functional aspects of disaster. They should not have multiple meanings

Sensemaking ia a big problem, especially when it comes to multiple stakeholders involved in a disaster (responders, victims, effected people, policy wonks, legislators, researchers, etc.)

Evokes boundary objects work

-

Disaster Phases Are Multidimensional Another component of the mutually inclusive nature of disaster phases is that they are multidimensional

Neal argues that individuals and groups, and subunits of each, may experience phases at different times.

-

Disaster Phases Are Mutually Inclusive As previously indicated, disaster phases overlap. From a theoretical and applied viewpoint, researchers and practitioners must first recognize that disaster phases are not discrete units.

Neal argues that disaster phases are interconnected and influence what happens (or does not happen) in other phases.

-

Second, the manner the field handles the issue of disaster phases actually reflects a larger problem in the field. Specifically, how do we define disaster? Kreps (1984, p. 324) comes closest to recognizing the relationship among disaster phases, the theoretical components of disaster (i.e., social order and social action), and the definition of disaster (primarily in a heading in his paper). Unfortunately, he does not elaborate upon the connection of defining disaster and disaster phases. Thus, recognizing and recasting our notion of disaster phases may actually help the field more precisely understand or define "disaster."

Has this changed since 1997? Cites a passage from Quarantelli that argues disaster research is not well defined.

Evokes Bowker and Star's boundary objects work.

-

Researchers have at times treated the disaster phases as scientific constructs to order data and for scientific analysis. However, as the organizational and family literature show, assumptions based on life-cycle approaches and assumptions often fall outside the realm of appropriate scientific analysis. Here, the phases within the disaster life cycle fall outside the scientific necessity of well-defined, mutually exclusive concepts.

Critique of scientific methods/needs for classification leading practitioner work astray. Good analogy with family life cycles.

-

One high-level manager involved with the Federal Response Plan made the following reflection about two weeks after Hurricane Andrew occurred: My feeling is that recovery needs to start day one, or even prior to a disaster. It would be wise to set up a group or task force, or a committee. They get together to gather information as the disaster begins. The potential for fragmentation is enormous. It actually goes back to intelligence, damage information. It is difficult to plan for recovery when you do 001 have a sense for how long it could take. You know, recovery has already begun. FEMA has already issued over one million dollars worth of checks .... Anyway, why not have a recovery unit? That would be cool. They should deal the long term recovery within hazard mitigation. In any event that needs to be happening ftom day one.

Interesting. This pretty much describes the SBTF mission, per the intelligence gathering.

-

Finally, the notation of the disaster phases affected emergency-responders' decisions. The lexicon of the four phases appeared to force disaster managers and responders to think and respond in a linear, separate-category fashion. Thus, this paradigm in the end can hurt effective response

Need to research whether these issues have been resolved or workarounds put in place since this 1997 publication. I kind of suspect not.

-

Addinonal �grecovery research by Phillips (1991) shows that different_ categones of disaster victims exit and enter disaster-housing phases at different nmes. She finds that some special-population groups ( e.g., elderly, Hispanics) take a much longer time to transition from temporary to pennanent sheltenng, and from sheltering to temporary and permanent housing than other popu· lation segments.

Example of the need for feminist/critical theory in crisis informatics research

-

Of equal importance, both structural-and nonstructural-mitigation techniques would lessen dramatically response needs. In essence, effective mitigation and preparation would lessen response time. Logically extended, effective mitigation and preparation when coupled with an effective response could decrease the time for both short-and long-tenn recovery. Tlus analysis further convinced me of the interconnectiveness of the disaster periods.

Another anecdote about de-coupling phase classifications from temporality in order to better describe what is happening. Need some sort of sliding scale.

-

In summary, the ECGs study from DRC showed me that the use of disaster periods created analytical problems. The categories often overlapped, different groups perceived and experienced the disaster phases differently, and individuals or groups defined differently the actual or potential event

Mismatch between disaster phase classifications and temporal periods of those phases as experienced by individuals/groups.

-

emergent citizen groups (ECGs) in disasters (e.g., Neal I 984, Quarantelli 1985)

How are emergent citizen groups defined? How is it similar/different than DHNs?

Get these papers.

-

Emergency response and recovery is not a linear process; decisions that are made during the emergency phase will impact the recovery process. In practice, however, recovery often takes place in an ad hoc fashion because key decisions are not part of a strategic program to restore services and rebuild communities. (Dumam et al. 1993, p. 30)

This practitioner critique gets at the importance of better understanding temporal sensemaking and enactment during disasters since decisions can influence across the different phases

-

Therefore, if disaster researchers wish to improve the theoretical development of the field dramatically, I argue that we should reanalyze the current heuristic related to the phases.

Is Neal still making this argument?

-

In fact, the Functions and Effects Study generated the notion that the relationship between mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery is not even linear. Rather, some preparedness activities (like educating government officials) could really have mitigation effects; and some recovery activities mitigate against future disasters (like using housing Joans to relocate residences out of a flood plain). The Functions and Effects experts hypothesized at least a cyclical relationship among !hese four phases of disaster activity. (National Governor's Association 1979:108)

Describes the phases as not linear, and more cyclical.

-

Others also allude to the fact that these categories are not mutually exclusive. Haas, Kates, and Bowden (1977) make the following important observation:

Phases may vary temporally, may overlap, differ in pace, and/or never come to a periodic conclusion depending on the pre-disaster built environment.

-

Despite a positive approach regarding time models, Stoddard concludes the discussion by saying, a simple or complex time model is not comprehensive enough by itself to integrate completely disaster research. Additional constructs are required for methodological and theoretical comparisons and liaisons between findings and the various disaster studies. (Stoddard 1968, p. 12)

Critique of incomplete temporal models for disaster research.

-

Since the beginning of the field, disaster researchers have observed various types of disaster periods. Specifically, different events seem to occur at different times related to a disaster. Also, both academics and practitioners assume that these phases exist, and act as if they do exist Yet, in the last 30 years or so, disaster researchers or practitioners have accomplished little in defining or refining the use of disaster phases. Yet, as I show in the next two sections, both researchers and practitioners have questioned the use of disaster phases since their initial use.

Is this criticism still true?

-

The National Governor's Association Report

History and updated information about the CEM:

-

Other empirical studies show that the recovery process is not a simple, linear, or cyclical process. Different units or groups may experience, or perceive that they experience, the different stages of recovery I) at different times and 2) at different rates of time.

Neal cites several studies that contend the recovery process is temporally complex.

-

Overall, recovery studies suggest that subcategories of the recovery process exist. However, different units of analysis (e.g., individual versus group) or different types of groups (e.g., based on ethnicity or social class) may experience the phases of recovery at differing rates. Thus, patterns, phrases or cycles of recovery are not linear.

Strong statement on how the unit of analysis can influence disaster research beyond theoretical frameworks and the need to look at temporality differently.

-

Phillips' (1991) analysis of housing following the Loma Prieta Earthquake confirms these different phases. Also, her study shows that different groups of people, often based upon such factors as social class or ethnicity, go through the phases of housing recovery at different times.

Makes a good case here for the need to use feminist and/or post-colonial lens to study disaster phases.

-

The edited work by Haas, Kates, and Bowden ( 1977) illustrates the complexity of the recovery process. Unlike most other overall codification efforts, the above authors explicitly recognize that recovery reflects a complex process. They note that people use several subcategories (e.g., restoration, recovery, rehabilitation, redevelopment, reconstruction) to describe aspects of the recovery period.

This classification of the recovery phase by Haas, Kates, and Bowden inclues more description of the phases but still cast it as a linear timeline.

-

In Drabek's (1986) more recent codification effort, he modifies the disaster phases. His revision reflects the language of the National Governor's Association's 1979 recommendations (i.e., preparedness, response, recovery, mitigation) of disaster phases.

Some of Drabek's updates include temporal markers (pre- and post-impact, periods of time, etc.) Neal continues to criticize the lack of definition and theory driving the evolution of classification.

The current NGA homeland security classifications are: Prepare, Prevent, Respond, Recover.

(https://www.nga.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/GovsGuidetoHomelandSecurity2010-FINAL.pdf )

-

Stoddard argues that the use of time-and-space models in disaster research

Complete quote runs over 2 pages: "Stoddard argues that the use of time-and-space models in disaster research provides an important methodological disaster research tool. Most important, he contends that the different phases of disaster represent different types of individual and group behavior."

Stoddard's definition offers a solid framework to begin the conversation about how and why it's important to understand the interaction between pluritemporal modes of time and humanitarian response (individual and group sensemaking and enactment).

-

By the 1960s, researchers had studied many disasters to allow codification efforts (Quarantelli and Dynes 1977). For some (e.g., Dynes 1970) disaster periods refer to a temporal category (e.g., before a disaster strikes, while a disaster strikes, after a disaster strikes). In other cases, the use of the phases may refer to functional activities that may or may not also be embedded with temporal considerations (stocking supplies, search and rescue, responding while the disaster strikes, attempting to recovery from the impact). For example, Barton (1970) combines both functional and temporal considerations of disaster. Yet, these and other writers never fully explored the theoretical implications of using the phases in their research

Early work to codify natural disasters relied in different degrees on the temporality of the event as a timeline of before/during/after.

Neal critiques this work as lacking in theoretical implications.

-

He adds that this phase could be important with sudden impacts, but not as important with slow-moving impacts.

Barton's definition of disaster phases (1970) includes event temporality: slow-moving vs sudden.

-

Disasters, Dynes argues, follow a general temporal sequence despite the agent. Dynes employs these phases to argue successfully for an "all hazards" approach to disaster

Dyne's definition evokes Powell's timeline approach to all disaster phases.

-

Mileti, Drabek, and Haas developed their six categories of: 1) preparedness/adjustment; 2) warning; 3) pre-impact, early actions; 4) post-impact, short-term actions; 5) relief or restoration, and 6) reconstruction. They justify these categories by noting that "Numerous researchers have documented how activities and nonnative definitions appear to vary across time and vary greatly among events" (Mileti, Drabek, Haas 1975, p. 9). The six phases serve as a central component of the authors' codification effort (it organizes the book chapters). Yet, the authors do not provide a more specific definition for each category. Other theoretical underpinnings in the book receive much more detailed justification (e.g., collective stress, social nature of disaster).

An update to Barton and Dyne's work by Mileti, Drabek and Haas continues to give short-shrift to theoretical underpinnings of the classifications, per Neal.

Evokes Bowker and Star's work on classifications.

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

It is boundaries that help us separate one entity from another: "To classify things is to arrange them in groups ... separated by clearly determined lines of demarcation .... At the bottom of our conception of class there is the idea of a circumscription with fixed and definite outlines. "7 Indeed, the word define derives from the Latin word for boundary, which is finis. To define something is to mark its boundaries, 8 to surround it with a mental fence that separates it from everything else. As evidenced by our failure to notice objects that are not clearly differentiated from their surroundings, it is their boundaries that allow us to perceive "things" at all.

Social reality is constructed by defining boundaries and visibility to objects. Evokes Bowker and Star's classification and boundary object framework.

-

Nonetheless, without some lumping, it would be impossible ever to experience any collectivity, or mental entity for that matter. The ability to ignore the uniqueness of items and regard them as typical members of categories is a prerequisite for classifying any group of phenomena. Such ability to "typify"106 our experience is therefore one of the cornerstones of social reality

Classification is the mechanism for making sense of disparate objects through the process of lumping and making differences invisible.

-

A mental field is basically a cluster of items that are more similar to one another than to any other item. Generating such fields, therefore, usually involves some lumping.

Evokes Bowker and Star's boundary object work re: the mental models of lumping and splitting

-

In order to endow the things we perceive with meaning, we normally ignore their uniqueness and regard them as typical members of a particular class of objects (a relative, a present), acts (an apology, a crime), or events (a game, a conference).2 After all, "If each of the many things in the world were taken as distinct, unique, a thing in itself unrelated to any other thing, perception of the world would disintegrate into complete meaninglessness. "3 Indeed, things become meaningful only when placed in some category.

Connect this to Bowker and Star (2000) Sorting Things Out.

-

- Dec 2018

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

Resistance Realily is 'that which resists,' according to Latour's (1987) Pragmatistinspired definition. The resistances thal designers and users encounter will change lhc ubiquitous networks of classifications and standards. Although convergence may appear at times to create an inescapable cycle of feedback and verification, the very multiplicity of people, things and processes involved mean lhat they are never locked in for all time.

Questioning the infrastructural inversion via ubiquity, material and texture, history, and power shapes the visibility and invisibility of the infrastructure that society creates for itself.

-

Infrastructure and Method: Convergence These ubiquitous, textured dai;sifications and standards help frame our representation of the past and the sequencing of event� in the present. They (:an best be understood as doing the ever local, ever partial work of making it appear that science describes nature (and nature alone) and that politics is about social power (and social power alone).

"Standards, categories, technologies, and phenomenology are increasingly converging in large-scale information infrastructure." (p. 47)

Convergence gets to how things work out as "scaffolding in the conduct of modern life."

-

Practical Politics �1 ·he fourch major theme is uncovering the practical politics of classifying awl standardizing. 'fhi<; is the de.sign end of the spectrum of investigating categories and standards as technologies. There are two processes associated with these politics: arriving at categories and standards, and, along the way, deciding what will be visible or invisible within the system.

Politics, as in power dynamics, leadership, negotiation, and decision-making authority, play a role in determining how classifications and standards infrastructures are perceived as visible/invisible.

-

The Indeterminacy of the Past: Multiple Times, Multiple Voices The third methodological theme concerns ihe f1asl as indetc,rr,1inate. 10 We are constantly revising our knowledge of the past in light of new developments in the present.

Visibility can be obtained by peeling back the history of the infrastructure -- how it began, how it was added to, how it changed/adapted over time.

Looking back in time also provides an opportunity to consider how different people/perspectives influenced the infrastructure. Who was vocal? Who was silent? Who was silenced?

-

Materiality and Texture The second methodological departure point is that. classifications and standards are material, as well as symbolic.

Another way to make infrastructures visible is to envision their physical presence (materiality) and texture (experience).

Metaphors play an important role here.

-

This categorical saturation furthermore forms a complex web. Although it is possible to pull out a single dassilication scheme or standard for reference purposes, in reality none of them stand alone. So a subproperty of ubiquity is interdependence, ,md frequently, integration. A systems approach might see the proliferation of both standards and classilications as purely a matter of integration-almost like a gigantic web of interoperability. Yet the sheer density of these phenomena go beyond questions of interoperability. They are layered, tangled, textured; they interact lo form an ecology as well as a flat set of compatibilities.

Ubiquitous classifications and standards are also interdependent and integrated, thus creating complex systems that work but the components of which tend to be invisible.

Example: Other classifications when the phenomena/object don't fit elsewhere or the "cumulative mess trajectory" which occurs when categories and standards interact in messy ways

-

Ubiquity The first major theme is the ubiquity of classifying and standardizing. Classification schemes and standards literally saturate our environment.

Methodological themes for infrastructural inversion -- how to make the invisible visible

-

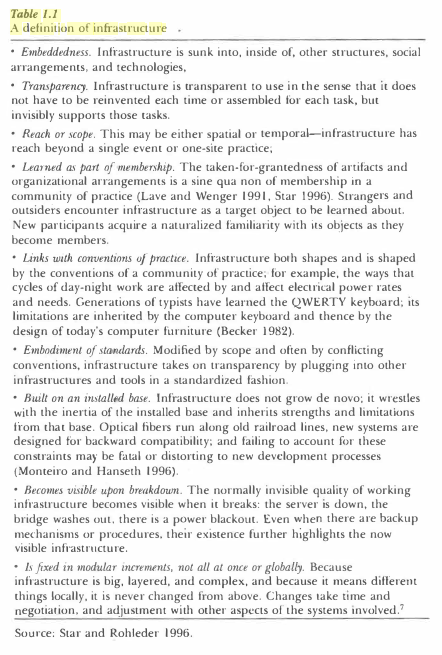

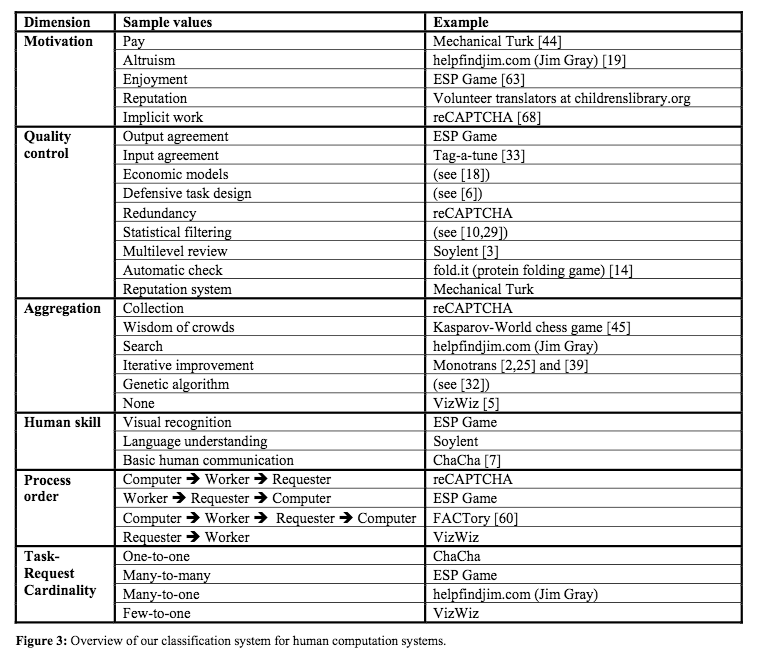

A definition of infrastructure

Definition of infrastructure

-

This chapter offers four themes, methodological points of departure for the analysis of these complex relationships. Each theme operates as a gestalt switch-it comes in the form of an i11fras/:ruclural inversion (Bowker 1994). This inversion is a struggle against the tendency of infrastructure to disappear (except when breaking down). Tt means learning to look closely at technologies and arrangements that, by design and hy habit, tend to fade into the woodwork (sometimes literally!). Infrastructural inversion means recognizing the depths of interdependence of technical networks and standards, on the one hand, and the real work of politics and knowledge production8 on the other.

Definition of infrastructural inversion

How normally invisible structures become visible (gestalt -- whole is perceived as more than the sum of its parts) when there is a breakdown

-

Standards Classifications and standards are closely related, but not identical. \-Vhile this book focuses on classificalion, standards are crucial components of the larger argument. The systems we discuss often do become standardized; in addition, a standard is in part a way of classifying the world. What then are standards? The term as we use it in the book has several dimensions:

Definition of standards

"What are standards?" Cited verbatim from the book

- A set of agreed-upon rules for the production of objects

- Spans more than one community of practice. It has temporal reach since it persists over time.

- Deployed in making things work together over distance and heterogeneous metrics

- Standards are enforced by some legal/regulatory/professional/government body.

- There is no natural law that the best standard wins

- Standards can be difficult and expensive to change

-

Infrastructures are never transparent for everyone, ancl lheir '\\•orkabilit y as they scale up becomes increasingly complex. Through due methodological attention to the architecture and use of these syslems, we can achieve a deeper understanding of how it is that individuals and communities meet infrastructure. ·we know that this means, at Lhe leasl, an understanding of infraslructure that includes these points:

Cited verbatim from book:

- A historical process of development of many tools, arranged for a wide variety of users and made to work in concert

- A practical match among routines of work practice, technology, and wider scale organizational and technical resources

- A rich set of negotiated compromises ranging from epistemology to data entry that are both available and transparent to communities of users

- A negotiated order in which all of the above, recursively, can function together.

-

The sheer density of the collisions of classification schemes in our lives calls for a new kind of science, a new set of metaphors, linking traditional social science and computer and information science. We need a tqpography of things such as the distribution of ambiguity; the fluid dynamics of how classification systems meet up-a plate tectonics rather than a static geology. This nevi science will draw on the best empirical studies of work-arounds, information use, and mundane tools such as desktop folders and file cabinets (perhaps peering backwards out frorn the Web and into the practices). It will also use the best of object-oriented programming and other areas of computer science to describe this territory. It will build on years of valuable research on classification in library and information s<:ience.

"Why it is important to study classification systems"

-

Information infrastrucLUre is a tricky thing to analyze_l; Good, usable systems disappear almost by deiinition. The easier they arc lo use, the harder they are to see.

The invisibility of infrastructure

-

A� we know from studies of work of all sorts, people do not do the ideal joh, but the doable job. \Vhen faced with too many alternatives and too much information, they satisfice (Mard1 and Simon 1958).

Satisficing as a sensemaking strategy

-

Forms like Lhe death certificate, ·when ag6TTcgated, form a case of what Kirk and Kutd1ins (1992) call "the substitution of precision for validity" (see also Star 1989b). That is, when a seemingly neutral data collection mechanism is substituted for ethkal conflict about the contents of the forms, the moral debate is partially erased. One may get ever more prn:ise knowledge, without having resolved deeper questions, and indeed, by burying those questions.

Real dilemma for humanitarian data: "the substitution of precision for validity"

-

Classifications may or may not become standardized. If they do not, they are ad hoc, limited to an individual or a local community, and/or of Limited duration. At the same time, every successful standard imposes a classification system, al the very least between good and bad ways of organizing acLions or things. And the work-arounds involved in the practical use of standards frequently entail the use of ad hoc nonstandard categories.

This is an important point for classifying and standardizing modes of time and temporal representations in information systems. What comes first? The class or the standard?

-

Nomenclature and dassifi<:at..ion are frequently confused, howevc1; since attempts are often made to model nomenclature on a 1>ingle, stable system of classification principles, as for example with bot.any (Bowke1; in press) or anatomy.

Nomenclature is an "agreed-upon naming scheme, one that does not follow any classificatory principles."

-

Clas.�ification A classification is a spatial, temporal, or sjH1ti11-lemporal segmm,tation rif lhe world. ,\ "classification system" is a set of boxes (rnelaphorical or literal) inlo which things can be pul to then do some kind of work-bureaucratic or knowledge production. In an abstract, .ideal sense, a classification system exhibits the frillowing properties:

Definition of classification

"A classification system exhibits the following properties:"

- There are consistent, unique classificatory principles in operation

- The categories are mutually exclusive

- The system is complete

-

vVe have a moral and ethical agenda in our querying of these systems. Each standard and each category valorizcs some point of view and silences another. This is not inherently a bad thing-indeed it is inescapable.

Key point here about the power of classification to make objects/phenomena visible or invisible.

In thinking about classifications of time/temporality, what does the standardization of some forms (ISO, commonly accepted terms/metaphors) say about the systems we design to account for time-based information? Is it simply an argument of ease/difficulty in formatting temporal data or is there some other social/cultural issue at play?

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

Table 1.1 A definition of infrastructure

Definition of infrastructure

-

This categorical saturation furthermore forms a complex web. Although it is possible to pull out a single classification scheme or standard for reference purposes, in reality none of them stand alone. So a_ subproperty of ubiquity is interdependence, and frequently, integrat10n. A systems approach might see the proliferation of both standards and classifications as purely a matter of integration-almost like a gigantic web of interoperability. Yet the sheer density of these phenomena go beyond questions of interoperability. They are layered, tangled, textured; they interact to form an ecology as well as a flat set of compatibilities.

Ubiquitous classifications and standards are also interdependent and integrated, thus creating complex systems that tend to be invisible.

Example: Other classifications when the phenomena/object don't fit elsewehre or the "cumulative mess trajectory" which occurs when categories and standards interact in messy ways

-

Ubiquity __ The first major theme is the ubiquity of classifying and standardmng. Classification schemes and standards literally saturate our environment.

Methodological themes for infrastructural inversion -- how to make the invisible visible

-

This chapter offers four themes, methodological points of departure for the analysis of these complex relationships. Each theme operates as a gestalt switch-it comes in the form of an infrastructural inversion (Bowker 1994). This inversion is a struggle against the tendency of infrastructure to disappear (except when breaking down). It means learning to look closely at technologies and arrangements that, by design and by habit, tend to fade into the woodwork (sometimes literally!). Infrastructural inversion means recognizing the depths of interdependence of technical networks and standards, on the one hand, and the real work of politics and knowledge production8 on the other.

Definition of infrastructural inversion

How normally invisible structures become visible (gestalt -- whole is perceived as more than the sum of its parts) when there is a breakdown

-

Infrastructures are never transparent for everyone, and their workability as they scale up becomes increasingly complex. Through due methodological attention to the architecture and use of these systems, we can achieve a deeper understanding of how it is that individuals and communities meet infrastructure. We know that this means, at the least, an understanding of infrastructure that includes these points:

Cited verbatim from book:

• A historical process of development of many tools, arranged for a wide variety of users and made to work in concert • A practical match among routines of work practice, technology, and wider scale organizational and technical resources • A rich set of negotiated compromises ranging from epistemology to data entry that are both available and transparent to communities of users • A negotiated order in which all of the above, recursively, can function together.

-

Information infrastructure is a tricky thing to analyze.6 Good, usable systems disappear almost by definition. The easier they are to use, the harder they are to see. As well, most of the time, the bigger they are, the harder they are to see.

The invisibility of infrastructure

-

The sheer density of the collisions of classification scheme� in_ our liv�s calls for a new kind of science, a new set of metaphors, hnkmg traditional social science and computer and information scien�e. We ne�d a topography of things such as the distribution of ambiguity; the flu_,d dynamics of how classification systems �eet u�-a plate tectomcs rather than a static geology. This new science will draw on the best empirical studies of work-arounds, info�mation use, and �undan_e tools such as desktop folders and file cabmets (perhaps peering backwards out from the Web and into the practices). It will also use th<: best of object-oriented programming and other areas of compute, science to describe this territory. It will build on years of valuablt research on classification in library and information science.

"Why it is important to study classification systems"

-

s we know from studies of work of all sorts, people do not do the ideal job, but the doable job. When faced with too many alternatives and too much information, they satisfice (March and Simon 1958).

Satisficing as a sensemaking strategy

-

Forms like the death certificate, when aggregated, form a case of what Kirk and Kutch ins ( 1992) call "the substitution of precision for validity" (see also Star 1989b). That is, when a seemingly neutral data collection mechanism is substituted for ethical conflict about the contents of the forms, the moral debate is partially erased. One may get ever more precise knowledge, without having resolved deeper questions, and indeed, by burying those questions.

Real dilemma for humanitarian data: "the substitution of precision for validity"

-

Classifications may or may not become standardized. If they do not, they are ad hoc, limited to an individual or a local community, and/or of limited duration. At the same time, every successful standard imposes a classification system, at the very least between good and bad ways of organizing actions or things. And the work-arounds involved in the practical use of standards frequently entail the use of ad hoc nonstandard categories.

This is an important point for classifying and standardizing modes of time and temporal representations in information systems. What comes first? The class or the standard?

-

Standards Classifications and standards are closely related, but not identical. While this book focuses on classification, standards are crucial components of the larger argument. The systems we discuss often do become standardized; in addition, a standard is in part a way of classifying the world.

Definition of standards

"What are standards?"

- A set of agreed-upon rules for the production of objects

- Spans more than one community of practice. It has temporal reach since it persists over time.

- Deployed in making things work together over distance and heterogeneous metrics

- Standards are enforced by some legal/regulatory/professional/government body.

- There is no natural law that the best standard wins

- Standards can be difficult and expensive to change

-

Nomenclature and classification are frequently confused, however, since attempts are often made to model nomenclature on a single, stable system of classification principles,

Nomenclature is an "agreed-upon naming scheme, one that does not follow any classificatory principles."

-

Classification A classification is a spatial, temporal, or spatio-temporal segmentation of the world. A "classification system" is a set of boxes (metaphorical or literal) into which things can be put to then do some kind of work-bureaucratic 9r knowledge production.

Definition of classification

"A classification system exhibits the following properties:"

- There are consistent, unique classificatory principles in operation

- The categories are mutually exclusive

- The system is complete

-

We have a moral and ethical agenda in our querying of these systems. Each standard and each category valorizes some point of view and silences another.

Key point here about the power of classification to make objects/phenomena visible or invisible.

In thinking about classifications of time/temporality, what does the standardization of some forms (ISO, commonly accepted terms/metaphors) say about the systems we design to account for time-based information? Is it simply an argument of ease/difficulty in formatting temporal data or is there some other social/cultural issue at play?

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

rom this view of what culture is follows a view equally assured, of what describing it is-the writing out of systematic rules, an ethnographic algorithm, which, if followed, would make it possible so to operate, to pass (physical appearance aside) for a native. In such a way, extreme subjectivism is married to extreme formalism, with the expected result: an explosion of debate as to whether particular analyses (which come in the form of taxonomies, paradigms, tables, trees, and other ingenuities) reflect what the natives "really" think or are merely clever simulations, logically equivalent but substantively different, of what they think. ...

Geertz critique of the behaviorist fallacy also seems to touch on Bowker and Star's argument that meaningful classification comes from within a group not an external observer.

-

Analysis, then, is sorting out the structures of signification-what Ryle called established codes, a somewhat misleading expression, for it makes the enterprise sound too much like that of the cipher clerk when it is much more like that of the literary critic-and determining their social ground and import.

"sorting out the structures of signification ... and determining their social ground and import" seems akin to Bowker and Star's discussion about the social, ethical, and moral aspects of classification.

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

Moreover,one of the CSCW findings was that such categorization (and especially howcategories are collapsed into meta-categories) is inherently political. The pre-ferred categories and categorization will differ from individual to individual.

Categories have politics.

See: Suchman's 1993 paper

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/764c/999488d4ea4f898b5ac5a4d7cc6953658db9.pdf

-

- Nov 2018

-

Local file Local file

-

Ontology depth

I'm curious about the depth distribution to compare my findings on other classification systems, including Wikipedia categories: https://arxiv.org/abs/cs/0604036

-

- Sep 2018

-

faculty.georgetown.edu faculty.georgetown.edu

-

classification (which is furthermore one of its 'social functions)

Okay, yes, back in my jolts of fashion professional/academic wheelhouse. Classification IS a social function and a construct.

-

in the interests of a new object and a new language neither of which has a place in the field of the sciences that were to be brought peacefully together, this unease in classification being precisely the point from which it is possible to diagnose a certain mutation.

The word "classification" jolted my fashion. Seems like this sentence should be in my wheelhouse because classification is decidedly a determination of my jam, but dear dog, I can't. Can I get a translation of the translation please?

-

-

clark.cs.ucr.edu clark.cs.ucr.edu

-

CLARK is a software tool for classifying any type of DNA/RNA sequences

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

- Aug 2018

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

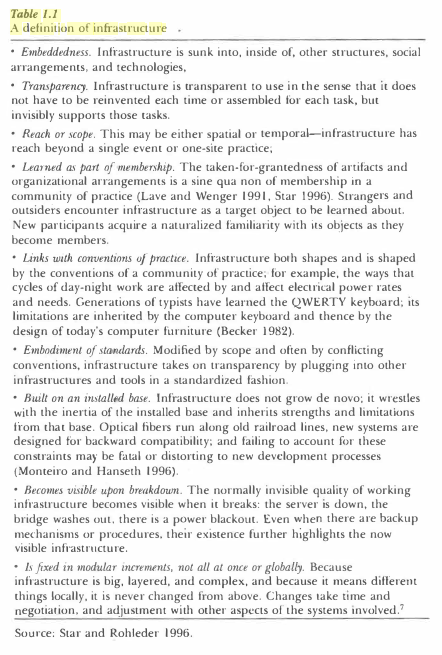

The classification system we are presenting is based on six of the most salient distinguishing factors. These are summarized in Figure 3.

Classification dimensions: Motivation, Quality control, Aggregation, Human skill, Process order, Task-Request Cardinality

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

hird, at this juncture, control is being equated with visibility and visibility with personal security. But how these individuals are made visible matters for both privacy and security, let alone the politics of conflating refugees, migration and terrorism. Indeed, working with specific data framing mechanisms affects how the causes and effects of disasters are identified and what elements and people are considered (Frickel 2008

A finer point on threat surveillance that stems from how classifications and categories are framed.

This also gets at post-colonial interpretations of people, places, and events.

See: Winner, Do Artifacts Have Politics? See: Bowker and Star, Sorting things out: Classification and its consequences. See: Irani, Post-Colonial Computing

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

In order to endow the things we perceive with meaning, we normally ignore their uniqueness and regard them as typical mem-bers of a particular class of objects (a relative, a present), acts (an apology, a crime), or events (a game, a conference).

Connect this to HCC reading: Bowker and Star (2000) Sorting Things Out.

-

- Jul 2016

-

books.google.ca books.google.ca

-

Page 122

Here Borgman suggest that there is some confusion or lack of overlap between the words that humanist and social scientists use in distinguishing types of information from the language used to describe data.

Humanist and social scientists frequently distinguish between primary and secondary information based on the degree of analysis. Yet this ordering sometimes conflates data sources, and resorces, as exemplified by a report that distinguishes quote primary resources, ed books quote from quote secondary resources, Ed catalogs quote. Resorts is also categorized as primary wear sensor data AMA numerical data and filled notebooks, all of which would be considered data in The Sciences. But rarely would book cover conference proceedings, and he sees that the report categorizes as primary resources be considered data, except when used for text or data mining purposes. Catalogs, subject indices, citation index is, search engines, and web portals were classified as secondary resources.

-

- Sep 2014

-

www.foreignpolicy.com www.foreignpolicy.com

-

Even though everyone knows Israel has the bomb, if you have a clearance and want to keep it, stick to discussing Israel's stockpile of strategic kumquats.

-