the meaning of essay which in English means also to try something

-the.meaning.of?essay-is

the meaning of essay which in English means also to try something

-the.meaning.of?essay-is

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Sumary:

This study evaluates whether species can shift geographically, temporally, or both ways in response to climate change. It also teases out the relative importance of geographic context, temperature variability, and functional traits in predicting the shifts. The study system is large occurrence datasets for dragonflies and damselflies split between two time periods and two continents. Results indicate that more species exhibited both shifts than one or the other or neither, and that geographic context and temp variability were more influential than traits. The results have implications for future analyses (e.g. incorporating habitat availability) and for choosing winner and loser species under climate change. The methodology would be useful for other taxa and study regions with strong community/citizen science and extensive occurrence data.

We thank Reviewer 1 for their time and expertise in reviewing our study. The suggestions are very helpful and will improve the quality of our manuscript.

Strengths:

This is an organized and well-written paper that builds on a popular topic and moves it forward. It has the right idea and approach, and the results are useful answers to the predictions and for conservation planning (i.e. identifying climate winners and losers). There is technical proficiency and analytical rigor driven by an understanding of the data and its limitations.

We thank Reviewer 1 for this assessment.

Weaknesses:

(1) The habitat classifications (Table S3) are often wrong. "Both" is overused. In North America, for example, Anax junius, Cordulia shurtleffii, Epitheca cynosura, Erythemis simplicicollis, Libellula pulchella, Pachydiplax longipennis, Pantala flavescens, Perithemis tenera, Ischnura posita, the Lestes species, and several Enallagma species are not lotic breeding. These species rarely occur let alone successfully reproduce at lotic sites. Other species are arguably "both", like Rhionaeschna multicolor which is mostly lentic. Not saying this would have altered the conclusions, but it may have exacerbated the weak trait effects.

We thank the reviewer for their expertise on this topic. We obtained these habitat classifications from field guides and trait databases, and reviewed our primary sources to clarify the trait classifications. We reclassified the species according to the expertise of this reviewer and perform our analysis again; please see details below.

(2) The conservative spatial resolution (100 x 100 km) limits the analysis to wide- ranging and generalist species. There's no rationale given, so not sure if this was by design or necessity, but it limits the number of analyzable species and potentially changes the inference.

It is really helpful to have the opportunity to contextualize study design decisions like this one, and we thank the reviewer for the query. Sampling intensity is always a meaningful issue in research conducted at this scale, and we addressed it head-on in this work.

Very small quadrats covering massive geographical areas will be critically and increasingly afflicted by sampling weaknesses, as well as creating a potentially large problem with pseudoreplication. There is no simple solution to this problem. It would be possible to create interpolated predictions of species’ distributions using Species Distribution Models, Joint Species Distribution Models, or various kinds of Occupancy Models. None of these approaches then leads to analyses that rely on directly observed patterns. Instead, they are extrapolations, and those extrapolations typically fail when tested, although they have still been tested (for example, papers by Lee-Yaw demonstrate that it is rare for SDMs to predict things well; occupancy models often perform less well than SDMs and do not capture how things change over time - Briscoe et al. 2021, Global Change Biology). The result of employing such techniques would certainly be to make all conclusions speculative, rather than directly observable.

Rather than employing extrapolative models, we relied on transparent techniques that are used successfully in the core macroecology literature that address spatial variation in sampling explicitly and simply. Moreover, we constructed extensive null models that show that range and phenology changes, respectively, are contrary to expectations that arise from sampling difference. 100km quadrats make for a reasonable “middle-ground” in terms of the effects of sampling, and we added a reference to the methods section to clarify this (see details below).

(3) The objective includes a prediction about generalists vs specialists (L99-103) yet there is no further mention of this dichotomy in the abstract, methods, results, or discussion.

Thank you for pointing this out - it is an editing error that should have been resolved prior to submission. We replaced the terms specialist and generalist with specific predictions based on traits (see details below).

(4) Key references were overlooked or dismissed, like in the new edition of Dragonflies & Damselflies model organisms book, especially chapters 24 and 27.

We thank Reviewer 1 for making us aware of this excellent reference. We have reviewed the text and include it as a reference, in addition to other references recommended by Reviewer 1 and other reviewers (see details below).

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

This paper explores a highly interesting question regarding how species migration success relates to phenology shifts, and it finds a positive relationship. The findings are significant, and the strength of the evidence is solid. However, there are substantial issues with the writing, presentation, and analyses that need to be addressed. First, I disagree with the conclusion that species that don't migrate are "losers" - some species might not migrate simply because they have broad climatic niches and are less sensitive to climate change. Second, the results concerning species' southern range limits could provide valuable insights. These could be used to assess whether sampling bias has influenced the results. If species are truly migrating, we should observe northward shifts in their southern range limits. However, if this is an artifact of increased sampling over time, we would expect broader distributions both north and south. Finally, Figure 1 is missed panel B, which needs to be addressed.

We thank Reviewer 2 for their time and expertise in reviewing our study.

It is possible that some species with broad niches may not need to migrate, although in general failing to move with climate change is considered an indicator of “climate debt”, signaling that a species may be of concern for conservation (ex. Duchenne et al. 2021, Ecology Letters). We revised the discussion to acknowledge potential differences in outcomes (please see details below).

We used null models to test whether our results regarding range shifts were robust, and if they varied due to increased sampling over time. We found that observed northern range limit shifts are not consistent with expectations derived from changes in sampling intensity (Figure S1, S2).

We thank Reviewer 2 for pointing out this error in Figure 1. This conceptual figure was a challenge to construct, as it must illustrate how phenology and range shifts can occur simultaneously or uniquely to enable a hypothetic odonate to track its thermal niche over time. In a previous version of the figure, we had a second panel and we failed to remove the reference to that panel when we simplified the figure. We have updated the figure and figure caption (please see details below).

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

Summary:

In their article "Range geographies, not functional traits, explain convergent range and phenology shifts under climate change," the authors rigorously investigate the temporal shifts in odonate species and their potential predictors. Specifically, they examine whether species shift their geographic ranges poleward or alter their phenology to avoid extreme conditions. Leveraging opportunistic observations of European and North American odonates, they find that species showing significant range shifts also exhibited earlier phenological shifts. Considering a broad range of potential predictors, their results reveal that geographical factors, but not functional traits, are associated with these shifts.

We thank Reviewer 3 for their expertise and the time they spent reviewing our study. Their suggestions are very helpful and will improve the quality of our manuscript.

Strengths:

The article addresses an important topic in ecology and conservation that is particularly timely in the face of reports of substantial insect declines in North America and Europe over the past decades. Through data integration the authors leverage the rich natural history record for odonates, broadening the taxonomic scope of analyses of temporal trends in phenology and distribution to this taxon. The combination of phenological and range shifts in one framework presents an elegant way to reconcile previous findings improving our understanding of the drivers of biodiversity loss.

We thank Reviewer 3 for this assessment.

Weaknesses:

The introduction and discussion of the article would benefit from a stronger contextualization of recent studies on biological responses to climate change and the underpinning mechanism.

The presentation of the results (particularly in figures) should be improved to address the integrative character of the work and help readers extract the main results. While the writing of the article is generally good, particularly the captions and results contain many inconsistencies and lack important detail. With the multitude of the relationships that were tested (the influence of traits) the article needs more coherence.

We thank Reviewer 3 for these suggestions. We revised the introduction and discussion to better contextualize species’ responses to climate change and the mechanisms behind them (see details below). We carefully reviewed all figures and captions, and made changes to improve the clarity of the text and the presentation of results (see details below).

Reviewer #1 (Recommendations for the authors):

Comment:

(1) Following weakness #1 in the public review, the authors should review the habitat classifications, consult with an odonatologist, and reclassify many species from Both to Lentic and redo the analysis.

Thank you for pointing out this disagreement among expert habitat classifications that we cited and other literature. We reclassified species’ habitat preferences based on classifications by Hof et al., a source that was consistent with your suggestions, and identified additional species as Lentic that our other references had identified as Both. We performed our analysis with this new dataset and, as you suspected, our results did not change qualitatively: species habitat preferences did not predict their range shifts.

Hof, Christian, Martin Brändle, and Roland Brandl. "Lentic odonates have larger and more northern ranges than lotic species." Journal of Biogeography 33.1 (2006): 63-70.

Comment:

(2) Following weakness #2, would it be worthwhile or interesting to analyze a smaller ranging group (e.g. cut the quad size in half, 50 x 50 km) to bring in more species and potentially change the inference? Or is the paper too tightly constructed to allow this, even as a secondary piece?

Thank you for this comment, as it highlights an important consideration for macroecological analyses, and the importance of balancing multiple factors for determining quadrat size. Issues exist with identifying drivers of range boundaries among species with narrow ranges when they are analyzed separately from wide-ranging species, and examining larger quadrats can actually help clarify drivers (Szabo, Algar, and Kerr 2009). The smaller quadrats are, the higher the likelihood that the species is actually there but was never observed, or that the quadrat only covers unsuitable habitat and the species is absent from the entire (or almost entire) quadrat. Too many absences creates issues with violating model assumptions, and creates noise that makes it difficult to identify drivers of species’ range and phenology shifts.

Moreover, we constructed extensive null models that show that range and phenology changes, respectively, are contrary to expectations that arise from sampling difference. 100km quadrats make for a reasonable “middle-ground”, and we have included a brief explanation of this in the text: “We assigned species presences to 100×100 km quadrats, a scale that is large enough to maintain adequate sampling intensity but still relevant to conservation and policy (Soroye et al., 2020), to identify the best sampled species.” (Lines 170-172).

Szabo, Nora D., Adam C. Algar, and Jeremy T. Kerr. "Reconciling topographic and climatic effects on widespread and range‐restricted species richness." Global Ecology and Biogeography 18.6 (2009): 735-744.

Comment:

(3) Following weakness #3, are specialists the ones that "failed to shift" (L18)? If so please specify. The prediction about generalists vs specialists needs to be removed or incorporated in other parts of the paper.

Thank you for pointing this out, we intended to suggest that species with more generalist habitat requirements might be better able to shift, but ultimately found that traits did not predict species’ shifts. We corrected our prediction regarding habitat generalists as follows: “We predicted that species able to use both lentic and lotic habitats would shift their phenologies and geographies more than those able to use just one habitat type, as generalists outperform specialists as climate and land uses change (Ball-Damerow et al., 2015, 2014; Hassall and Thompson, 2008; Powney et al., 2015; Rapacciuolo et al., 2017).” (Lines 128-132).

Comment:

(4) Following weakness #4, cite Pinkert et al at lines 70-73 and Rocha-Ortega et al at lines 73-77 along with https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2019.2645. Add Sandall et al https:// doi.org/10.1111/jbi.14457 to L69 references.

Thank you for the excellent reference suggestions, we have added them as suggested (Lines 80, 86, 77).

Comment:

Other comments/suggestions:

(1) Title: consider adding temp variability 'Range geography and temperature variability, not functional traits,...'.

Thank you for this suggestion, we have added temperature variability to the title: “Range geography and temperature variability explain cross-continental convergence in range and phenology shifts in a model insect taxon”.

Comment:

(2) L125: is (northern) Mexico included in North America?

Yes, we did include observations from Northern Mexico, and have specified this in the text: “We retained ~1,100,000 records from Canada, the United States, and Northern Mexico, comprising 76 species (Figure 2).” (Lines 174-176).

Comment:

(3) L128: I'd label this section 'Temperature variability' rather than 'Climate data'.

Thank you, we agree that this is a more appropriate title for this section, and have replaced ‘Climate data’ with ‘Temperature variability’ (Line 185).

Comment:

(4) Table 2: why are there no estimates for the traits?

We apologise, this information should have been included in the main body of the manuscript, but was only explained in the Table 2 caption. We have added the following explanation: “Non-significant variables, specifically all functional traits, were excluded from the final models.”. (Line 312-323).

Comment:

(5) Figure 2: need to identify the A-D panels.

We apologise for this error and have clarified the differences between panels in the figure caption:

“Figure 2: Richness of 76 odonate species sampled in North America and Europe in the historic period (1980-2002; panes A and C) and the recent period (2008-2018; panes B and D). Species richness per 100 × 100 km quadrat is shown in panes A and B, while panes C and D show species richness per 200 × 200 km quadrat. Dark red indicates high species richness, while light pink indicates low species richness.” (Lines 1002-1006).

Comment:

(6) L163-173: I am not familiar with this analysis but it sounds interesting and promising, I am not sure if this can be clarified further. Why the -25 to 25, and -30 to 30, doesn't the -35 to 35 cover these? And what is meant by "include only phenology shifts that could be biologically meaningful", that larger shifts would not be meaningful or tied to climate change?

We used different cutoffs for phenology shifts to inspect for outliers that were likely to be errors, potentially do to insufficient sampling to calculate phenology. We clarified in the text as follows:

“We retained emergence estimates between March 1st and September 1st, as well as species and quadrats that showed a difference in emergence phenology of -25 to 25 days, -30 to 30 days, or -35 to 35 days between both time periods, to include only phenology shifts that could be biologically meaningful to environmental climate change (i.e. exclude errors).” (Lines 169-173).

Comment:

(7) L193-200: I agree but would make a distinction between ecological vs functional traits, as other studies view geographic traits as ecological manifestations of functional biology, e.g. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.07.001 and https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.biocon.2023.110098.

Thank you for this suggestion, and for making us aware of the thinking around range geographies as ecological traits. We have specified throughout the manuscript that the ‘traits’ we are considering are ‘functional traits’, changed the methods subsection title to “Range geographies and functional traits” (Line 252), and added a brief discussion of ecological traits: “Geographic range and associated climatic characteristics are often considered ecological traits, as they are consequences of functional traits and their interactions with geographic features (Bried and Rocha-Ortega, 2023; Chichorro et al., 2019).” (Lines 256-259).

Comment:

(8) L203: What's the rationale for egg-laying habitat as "biologically relevant to spatial and temporal responses to climate change"? That one's not as obvious as the others and needs a sentence more. Also, I am wondering why other traits were not considered here, like color lightness and voltinism. And why not wing size instead of body size, or better yet the two combined (wing loading) as a proxy for dispersal ability?

We agree that our rationale for using this trait should be better explained, and we have included the following explanation: “Egg laying habitat was assigned according to whether species use exophytic egg-laying habitat (i.e. eggs laid in water or on land, relatively larger in number), or endophytic egg-laying habitat (i.e. eggs laid inside plants, usually fewer in number); species using exophytic habitats are associated with greater northward range limit shifts (Angert et al., 2011).” (Lines 271-275).

We considered traits that have been found to be important for range and phenology shifts among odonates, as well as being key traits for expectations for species responses to climate change. Flight duration and body size are correlated with dispersal ability (Powney et al. 2015). Body size is also correlated with competitive ability (Powney et al. 2015), potentially making it an important predictor of a species’ ability to establish and maintain populations in expanding range areas. Traits correlated with range shifts also include breeding habitat type (Powney et al. 2015; Bowler et al. 2021) and egg laying habitat (Angert et al. 2011). Ideally, we would have used dispersal data from mark/release/recapture studies, but it was not available for many of the species included in this study. After finding that none of the functional traits we included were related to range shifts, there was no reason to believe that a further investigation of traits would be meaningful.

Angert AL, Crozier LG, Rissler LJ, Gilman SE, Tewksbury JJ, Chunco AJ. 2011. Do species’ traits predict recent shifts at expanding range edges? Ecology Letters 14:677–689. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01620.x

Bowler DE, Eichenberg D, Conze K-J, Suhling F, Baumann K, Benken T, Bönsel A, Bittner T, Drews A, Günther A, Isaac NJB, Petzold F, Seyring M, Spengler T, Trockur B, Willigalla C, Bruelheide H, Jansen F, Bonn A. 2021. Winners and losers over 35 years of dragonfly and damselfly distributional change in Germany.Diversity and Distributions 27:1353–1366. doi:10.1111/ddi.13274

Powney GD, Cham SSA, Smallshire D, Isaac NJB. 2015. Trait correlates of distribution trends in the Odonata ofBritain and Ireland. PeerJ 3:e1410. doi:10.7717/peerj.1410

Comment:

(9) L210: I count at least 5 migratory species in table S3, so although maybe not enough to analyze it's misleading to say "nearly all" were non-migratory, revise to "most" or "vast majority".

Thank you for pointing this out, we have made the suggested correction (Line 277).

Comment:

(10) L252-254: save this for the Discussion and write a more generalized statement for results to avoid citations in the results.

Thank you for this suggestion, we have moved this to the discussion (Lines 517-527).

Comment:

(11) Figures S5 & S6: these are pretty important, I'd consider elevating them to the main document as one figure with two panels.

Thank you for this suggestion, we agree these figures should be elevated to the main text, and have made them into a panel figure (Figure 4).

Comment:

(12) L305-307: great point and recommendation!

Thank you very much for this positive feedback!

Comment:

(13) L335-336: another place to cite https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2019.2645 which includes a thermal sensitivity index and would add an odonate citation behind the statement.

Thank you for this excellent suggestion, we have added this citation (line 480). (Rocha-Ortega et al. 2020)

Comment:

(14) L352-353: again see also https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2019.2645.

Thank you for highlighting this reference, we have added it to Line 505 as suggested.

Comment:

(15) L355: revise "populations that coexist" to "species that co-occur" (big difference between population and species levels and between coexistence and co-occurrence).

Thank you very much for pointing this out, we have made the suggested change (Line 507).

Comment:

(16) L359-365: are the winners and losers depicted in Figures S5 & S6? If so reference the figure (which I suggest combining and promoting to the main text), if not create a table listing the analyzed species and their winner/loser status.

We agree that this is an excellent place to bring up Figures S5 and S6 from the supplemental. We have moved them to the main document as one figure and referenced it at line 510.

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations for the authors):

Comment:

(1) Line 53-55: The claim that "These relationships generalize poorly taxonomically and geographically" is valid, but the study only tests Odonata on two continents.

Thank you for this comment – the word ‘generalize’ may imply that our study tries to find a general pattern across many groups. We have changed the language to: “However, these relationships are inconsistent across taxa and regions, and cross-continental tests have not been attempted (Angert et al., 2011; Buckley and Kingsolver, 2012; Estrada et al., 2016; MacLean and Beissinger, 2017).” (Lines 57-59).

Comment:

(2) Line 58-59: Is this statement only true for Odonata? It does not seem to hold for plants, for example.

Thank you for this comment – this statement references a meta-analysis of multiple animal and plant taxa, but the evidence for the importance of range location comes from animal taxa. We have specified that we are referring to animal species to clarify (Line 60).

Comment:

(3) Line 87-91: This section is difficult to understand and needs clarification.

We have clarified this section as follows: “While warm-adapted species with more equatorial distributions could expand their ranges poleward following warming (Devictor et al., 2008), they could also increase in abundance in this new range area relative to species that historically occupied those areas and are less heat-tolerant (Powney et al., 2015).” (Lines 95-121).

Comment:

(4) Line 99-100: Please define "generalist" and "specialist" more clearly here (e.g., based on climate niche?).

Thank you for pointing this out, we intended to suggest that species with more generalist habitat requirements might be better able to shift, but ultimately found that traits did not predict species’ shifts. We corrected our prediction regarding habitat generalists as follows: “We predicted that species able to use both lentic and lotic habitats would shift their phenologies and geographies more than those able to use just one habitat type, as generalists outperform specialists as climate and land uses change (Ball-Damerow et al., 2015, 2014; Hassall and Thompson, 2008; Powney et al., 2015; Rapacciuolo et al., 2017).” (Lines 128-132).

Comment:

(5) Line 122: Replace the English letter "X" in "100x100 km" with the correct mathematical symbol.

We have made the suggested replacement throughout the manuscript.

Comment:

(6) Line 148: To address sampling effects, you could check the paper: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/gcb.15524. Additionally, maximum and minimum values are sensitive to extreme data points, so using 95% percentiles might be more robust.

Thank you for sharing this paper, as it offers a valuable perspective on the study of species’ ranges. While our dataset is substantially composed of observations from adult sampling protocols, unlike the suggested paper which compares adults and juveniles, this is an interesting alternative approach.

For our purposes it is meaningful to include outliers, as otherwise we may have missed individuals at the leading edge of range expansions. Our intent here was to detect range limits, as opposed to finding the central tendency of species distributions. This approach is widely accepted in the macroecology literature (i.e. Devictor et al., 2012, 2008; Kerr et al. 2015).

We have included the following discussion of our approach in the methods section:

“We followed widely accepted methods to determine species range boundaries (Devictor et al., 2012, 2008; Kerr et al., 2015), although other methods exist that are appropriate for different data types and research questions i.e. (Ni and Vellend, 2021). We assigned species presences to 100×100 km quadrats, a scale that is large enough to maintain adequate sampling intensity but still relevant to conservation and policy (Soroye et al., 2020), to identify the best sampled species.” (Lines 168-173).

Kerr JT, Pindar A, Galpern P, Packer L, Potts SG, Roberts SM, Rasmont P, Schweiger O, Colla SR, Richardson LL,Wagner DL, Gall LF, Sikes DS, Pantoja A. 2015. Climate change impacts on bumblebees converge across continents. Science 349:177–180. doi:10.1126/science.aaa7031

Soroye P, Newbold T, Kerr J. 2020. Climate change contributes to widespread declines among bumble bees across continents. Science 367:685–688. doi:10.1126/science.aax8591

Devictor V, Julliard R, Couvet D, Jiguet F. 2008. Birds are tracking climate warming, but not fast enough.Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 275:2743–2748. doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.0878

Devictor V, van Swaay C, Brereton T, Brotons L, Chamberlain D, Heliölä J, Herrando S, Julliard R, Kuussaari M,Lindström Å, Reif J, Roy DB, Schweiger O, Settele J, Stefanescu C, Van Strien A, Van Turnhout C,

Vermouzek Z, WallisDeVries M, Wynhoff I, Jiguet F. 2012. Differences in the climatic debts of birds and butterflies at a continental scale. Nature Clim Change 2:121–124. doi:10.1038/nclimate1347

Comment:

(7) Line 195: The species' climate niche should also be considered a product of evolution.

Thank you for this suggestion. To address this comment and a comment from another reviewer, we changed the text to the following: “Geographic range and associated climatic characteristics are often considered ecological traits, as they are consequences of functional traits and their interactions with geographic features (Bried and Rocha-Ortega, 2023; Chichorro et al., 2019).” (Lines 256-259).

Comment:

(8) Line 244: This speculative statement belongs in the Discussion section.

Thank you for this suggestion, we have moved this statement to the discussion (Lines 451-453).

Comment:

(9) Line 252-254: The projection of Coenagrion mercuriale's range contraction is not part of your results and should be clarified or removed.

Following this suggestion and a similar suggestion from another reviewer, we moved this text to the discussion (Line 517-527).

Comment:

(10) Line 314-316: If the species can tolerate warmer temperatures better, why would they migrate?

We apologize for the confusion, and we have reworded the section as follows: “Emerging mean conditions in areas adjacent to the ranges of southern species may offer opportunities for range expansions of these relative climate specialists, which can then tolerate climate warming in areas of range expansion better than more cool-adapted historical occupants (Day et al., 2018).” (Lines 445-448).

Comment:

(11) Line 334-335: Species' tolerance to temperature likely depends on their traits, which were not tested in this study. This should be noted.

We agree, and we have removed the wording “rather than traits” from this sentence (Line 479).

Reviewer #3 (Recommendations for the authors):

Comment:

(1) Title: The title is too general not specifying that your results are on odonates only, but also stressing the implicit role of climate change to a degree the tests do not support.

Following this comment and a suggestion from another reviewer we changed the title to the following: “Range geography and temperature variability explain cross-continental convergence in range and phenology shifts in a model insect taxon”. We wanted to emphasize our use of Odonates as a model species that we used to ask broad questions, while being more specific about the climatic variable that we examined (temperature variability).

Comment:

(2) L32: consider including Novella-Fernandez et al. 2023 (NatCommun) which addresses this topic in Odonates.

Thank you for suggesting this very interesting paper, we have added it as a citation (Line 31-32).

Comment:

(3) L35: consider including Grewe et al. 2013 (GEB) and Engelhardt et al. 2022(GCB).

Thank you for these excellent suggestions, we have added the citations (Line 35).

Comment:

(4) L47: rather write 'result from' instead of 'driven by'.

We agree this is a better characterization and have corrected the wording (Line 48-49).

Comment:

(5) L49-52: There has been a recent study on this topic for birds (Neate-Clegg et al., 2024 NEE). However, specifying this to insects would make it not less relevant. This review for odonates might be helpful in this regard (Pinkert et al.. 2022, Chapter: "Odonata as focal taxa for biological responses to climate change" IN Dragonflies & Damselflies: Córdoba-Aguilar et al. (2022) Model Organisms for Ecological and Evolutionary Research.

Thank you for again suggesting excellent references, we have added them to line 52-53, as well as adding the Pinkert citation to lines 61 and 82.

Comment:

(6) L53-66: Combine into one paragraph about drivers. With traits first and the environment second. The natural land cover perspective may be too complicated in this context. Consider focusing on generalities of the impact of changes within species' ranges.

As suggested we have combined these into one paragraph about drivers (Line 59).

Comment:

(7) L67-69: The book from before would be a much stronger reference for this claim. Kalkmann et al (2018) do not address the emphasis of global change research in insects on bees and butterflies. Also, I would highlight that most of the current work is at a national scale, rather than cross-continental.

Thank you for this suggestion, we have added the suggested reference and included that “…recently assembled databases of odonate observations provide a rare opportunity to investigate species’ spatiotemporal responses at larger taxonomic and spatial scales, particularly as most work has been done at national scales.” (Lines 75-77).

Comment:

(8) L68: consider rephrasing this part to '..provide a rare opportunity to investigate spatiotemporal biotic responses at larger taxonomic and spatial scales'

We appreciate this suggestion and really like the wording. We have changed the phrase to read as follows: “While global change research on insects often emphasizes butterfly and bee taxa, recently assembled databases of odonate observations provide a rare opportunity to investigate species’ spatiotemporal responses at larger taxonomic and spatial scales, particularly as most work has been done at national scales.” (Lines 74-77).

Comment:

(9) L69: This characteristic is not unique to odonates and would hamper drawing general conclusions. Honestly, I think the detailed and comprehensive data on them is the selling point.

Thank you for this suggestion, we have edited the sentence to emphasize their use as an indicator species: “Due to their use of aquatic and terrestrial habitat across life different stages, dragonflies and damselflies are also considered indicator species for both terrestrial and aquatic insect responses to changing climates (Hassall, 2015; Pinkert et al., 2022; Šigutová et al., 2025), giving the study of these species broad relevance for conservation.” (Lines 78-81)

Comment:

(10) L73: Indicator for what? The first part of the sentence would suggest lesser surrogacy for responses of other taxa. Reconsider this statement. They are well- established indicators for habitat intactness and freshwater biodiversity. Darwell et al. suggested their diversity can serve as a surrogate for the diversity of both terrestrial and aquatic taxa.

Thank you for this suggestion, we have edited the sentence to emphasize their use as an indicator species: “Due to their use of aquatic and terrestrial habitat across life different stages, dragonflies and damselflies are also considered indicator species for both terrestrial and aquatic insect responses to changing climates (Hassall, 2015; Pinkert et al., 2022; Šigutová et al., 2025), giving the study of these species broad relevance for conservation.” (Lines 78-81)

Comment:

(11) L76: Fritz et al., is a study on mammals, not odonates.

Thank you for pointing out this error, the reference has been removed (Line 84-85).

Comment:

(12) L84: Lotic habitats are generally better connected than lentic ones. Lentic species are considered to have a greater propensity for dispersal DUE to the lower inherent spatiotemporal stability (implying lower connectivity) compared to lotic habitats.

Thank you for your comment, we have rewritten this section as follows: “For example, differences in habitat connectivity and dispersal ability may constrain range shifts for lentic species (those species that breed in slow moving water like lakes or ponds) and lotic species (those living in fast moving-water) in different ways (Kalkman et al., 2018). More southerly lentic species may expand their range boundaries more than lotic species, as species accustomed to ephemeral lentic habitats better dispersers (Grewe et al., 2013), yet lotic species have also been found to expand their ranges more often than lentic species, potentially due to the loss of lentic habitat in some areas (Bowler et al., 2021).” (Lines 88-95).

Comment:

(13) L90: I would be cautious with this interpretation. If only part of the range is considered (here a country in the northern Hemisphere) southern species are moving more of their range into and northern species more of their range out of the study area in response to warming (implying northward shifts).

We have clarified this section as follows: “While warm-adapted species with more equatorial distributions could expand their ranges poleward following warming (Devictor et al., 2008), they could also increase in abundance in this new range area relative to species that historically occupied those areas and are less heat-tolerant (Powney et al., 2015).” (Lines 95-121)

Comment:

(14) L117: Odonata Central contains many county centroids as occurrence records. These could be an issue for your use case. I may have overlooked the steps you took to address this, but I think this requires at least more detail and possibly further removal/checks using for instance CoordinateCleaner. The functions implemented in this package allow you to filter records based on political units to avoid exactly this source of error.

Thank you for this suggestion, we weren’t aware of this issue with Odonata Central. We used the CoordinaterCleaner tool in R to filter all odonate records that we used in our analyses. Less than 1% of observations in our dataset were identified as having potential problems by the tool, so we would not expect this to affect our inferences. However, in future we will employ this tool when using similar datasets.

Comment:

(15) L119: Please add a brief explanation of why this was necessary. I am ok with something along the lines in the supplement.

We moved this information from the supplemental to the main text as follows: “If a species was found on both continents, we only retained observations from the continent that was the most densely sampled. If we merged data for one species found on both continents, we could not perform a cross-continental comparison. However, if the same species on different continents was treated as different species, this would lead to uninterpretable outcomes (and the creation of pseudo-replication) in the context of phylogenetic analyses. In addition, species found on both continents did not have sufficient data to meet criteria for the phenology analysis.” (Lines 161-167).

Comment:

(16) L132: This is the letters 'X' or 'x' are not multiplier symbols! Please change to the math symbol (×), everywhere.

Thank you for pointing out this error, we have made the correction throughout the manuscript.

Comment:

(17) L133: add 'main' before 'flight period'

Thank you for this suggestion, we have made the change. (Line 190)

Comment:

(18) L135: I suggest using the coefficient of variation, as it is controlled for the mean. Otherwise, what you see is partly the signature of temperature and not of its variation. For me, it's very difficult to understand what this variation of the variation means and at least needs more explanation.

Thank you very much for this suggestion, we agree that using the coefficient of variation is a better fit for the question that we’re asking. We re-ran out analyses with the coefficient of variation as the measure of climate variability: all the results reported in the manuscript are now updated for that analysis (Line 377, Table 2), and we have also updated the methods section (Line 191). The results are qualitatively the same to our previous analysis, but we agree that they are now easier to interpret.

Comment:

(19) L155: Please adequately reference all R packages (state the name, and a reference for them including the authors' names, title, and version).

Thank you for pointing out this omission, we have added reference information for the glm function in base R (Line 298) and ensured all other packages are properly referenced.

Comment:

(20) L207: Mention the literature sources here (again).

We agree that they should be referenced here again, and we have done so (Lines 267-268).

Comment:

(21) L209: You could use the number of grid cells as a proxy for range size.

Following this excellent suggestion, we re-analysed our data using range size, calculated as the number of quadrats occupied by a species in the historical time period, as a predictor. Range size was not significant in our models, but we believe this is the best way to analyze our data, and so have updated our methods (Lines 261-263) and results (375-378).

Comment:

(22) L218: It would be preferable to say 'species-level' instead of 'by-species'.

Thank you for this suggestion, we agree that this is clearer and made the change (Line 298).

Comment:

(23) L219-220: this is unclear. Please rephrase.

We have clarified as follows: “We used both species-level frequentist (GLM; glm function in R) and Bayesian (Markov Chain Monte Carlo generalized linear mixed model, MCMCglmm; Hadfield, 2010) models to improve the robustness of the results.” (Lines 298-300).

Comment:

(24) L224: At least for Europe there is a molecular phylogeny available, which you should preferably use (Pinkert et al. 2018, Ecography). Otherwise, I am ok with using what is available

We apologize that the nature of the phylogeny that we used was not clear; the phylogeny that we used was built similarly to that in Pinkert et al. 2018, Ecography. It created a molecular phylogeny with a morphological/taxonomic tree as the backbone tree, so that species could only move within their named genera or families. We clarified this in the manuscript as follows:

“We used the molecular phylogenetic tree published by the Odonate Phenotypic Database (Waller et al., 2019), which used a morphological and taxonomic phylogeny as the backbone tree, allowing species to move within their named genera or families according to molecular evidence (Waller and Svensson, 2017).” (Lines 302-305).

Comment:

(25) L233: You said so earlier (1st sentence of this paragraph).

Thank you for pointing this out, we removed the repetitive sentence (Line 323).

Comment:

(26) L236-238: To me, it makes more sense to test this prior to fitting the phylogenetic models.

MCMC-GLMM is considerably less familiar to most researchers than general linear models or there derivatives/descendants, such as PGLS. We report models both with and without phylogenetic relationships included for the sake of transparency, and we are happy to acknowledge that no interpretation here changes substantially relative to these decisions. However, failing to report models that included possible (if small) effects of phylogenetic relatedness might cause some readers to question what those models might have implied. For the moment, we are opting for the most transparent reporting approach here.

Comment:

(27) L241: Rather say directly XX of XX species in our data....

(28) L245: Same here. Provide the actual numbers, please.

Thank you for this suggestion, we made this change on Line 332 and Line 334.

Comment:

(29) L247-249: Then not necessary.

This issue highlights a challenge in the global biology literature and around the issue of biodiversity monitoring for understanding global change impacts on species. Almost no studies have been able to report simultaneous range and phenology shifts, and the literature addresses these biotic responses to global change predominantly as distinct phenomena. Differences in numbers of species for which these observations exist, even among the extremely widely-observed odonates, seems to us to be a meaningful issue to report on. If the reviewer prefers that we abbreviate or remove this sentence, we are happy to do so.

Comment:

(30) L251:261: That is discussion as you interpret your results.

Following your suggestion and the suggestion of another reviewer, we moved the following lines to the discussion section: “Species that did not shift their ranges northwards or advance their phenology included Coenagrion mercuriale, a European species that is listed as near threatened by the IUCN Red List (IUCN, 2021), and is projected to lose 68% of its range by 2035 (Jaeschke et al., 2013).” (Lines 517-527).

Comment:

(31) 252: Good to mention, but why is the discussion limited to C. mercurial?

We feel that it is important to link the broad-scale results to the specific biological characteristics of individual species, and C. mercurial is an IUCN threatened species. We are happy to expand links to natural history of this group and have added the following: “This group also includes Coenagrion resolutum, a common North American damselfly (Swaegers et al., 2014), for which we could not find evidence of decline. This may be due in part to the greater area of intact habitat available in North American compared to Europe, enabling C. resolutum to maintain larger populations that are less vulnerable to stochastic climate events. Still, this and other species failing to shift in range or phenology should be assessed for population health, as this species could be carrying an unobserved extinction debt.” (Lines 527-533).

Comment:

(32) L264: Insert 'being' before 'consistently'.

Thank you for the suggestion, we made this change (Line 373).

Comment:

(33) L271: .'. However,'.

Thank you for pointing out this grammatical error, we have corrected it (Line 382).

Comment:

(34) L273: 'affected' instead of 'predicted'

Thank you for the suggestion, we made this change (Line 383).

Comment:

(35) L279: 'despite pronounced recent warming' sounds not relevant in this context.

Thank you for this suggestion, we removed this portion of the sentence (Line 408).

Comment:

(36) L281: Rather 'the model performance did not improve....'

Thank you for the suggestion, we made this change (Line 409).

Comment:

(37) L288: Add 'but' before 'not'.

Thank you for the suggestion, we made this change (Line 416).

Comment:

(38) L311-316: Reconsider the causality here. maybe rather rephrase to are associated instead. Greater dispersal ability and developmental plasticity might well lead to higher growth rates, rather than the other way around.

We agree that plasticity/evolution at range edges is important to consider and have included it as an alternative explanation: “Adaptive evolution and plasticity may enable higher population growth rates in newly-colonized areas (Angert et al., 2020; Usui et al., 2023), but this possibility can only be directly tested with long term population trend data.” (Line 449-451).

Comment:

(39) L313-316: Maybe delete the second 'should be able to'.

This phrase has been changed in response to other reviewer comments and now reads as follows:

“Emerging mean conditions in areas adjacent to the ranges of southern species may offer opportunities for range expansions of these relative climate specialists, which can then tolerate climate warming in areas of range expansion better than more cool-adapted historical occupants (Day et al., 2018).” (Lines 445-448).

Comment:

(40) L331: Limit this statement ending with 'in North American and European Odonata'.

Thank you for this suggestion, we made this addition (Lines 475-476).

Comment:

(41) L346-347: There are too many of these more-research-is-needed statements in the discussion (at least three in the last paragraphs). Please consider finishing the paragraphs rather with a significance statement.

Thank you for this suggestion, we have changed the final sentence here to the following: “The extent to which species’ traits actually determine rates of range and phenological shifts, rather than occasionally correlated with them, is worth considering further, but functional traits do not systematically drive patterns in these shifts among Odonates in North America and Europe.” (Lines 480-483).

We also made additional changes, removing a ‘more-research is needed’ statement from the following paragraph (Line 443), as well as from line 499.

Comment:

(42) L349: See also Franke et al. (2022, Ecology and Evolution).

Thank you for highlighting this excellent reference! We have added it to Line 501.

Comment:

(43) L363: Maybe a bit late in the text, but it is important to note that there is the third dimension 'abundance trends' or rather a common factor related to range and phenology shifts. I feel this fits better with the discussion of population growth.

Thank you for this suggestion, we have addressed the importance of abundance trends in the following sentences: “Further mechanistic understanding of these processes requires abundance data.” (Lines 442-443); “It remains unclear if range and phenology shifts relate to trends in abundance, but our results suggest that there are clear ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ under climate change.” (Lines 509-510).

Comment:

(44) L375-377: This last sentence is very similar to L371-373. Please reduce the redundancy. Focus more on specifically stating the process instead of vaguely saying 'new insights into patterns' and 'suggesting processes'. Rather, deliver a strong concluding message here.

Thank you for this suggestion, we feel that we now have a much stronger concluding message: “By considering both the seasonal and range dynamics of species, emergent and convergent climate change responses across continents become clear for this well-studied group of predatory insects.” (Lines 545-547).

Comment:

(45) Table 1: To me, the few estimates presented here do not justify a table. rather include them in the text. OR combine them with Table 2. Also, why not include the traits as predictors (from the range shift models) in these models as well?

We have clarified in the text that the results displayed in Table 1 are from the analysis of the relationship between range and phenology shifts: “The effect of species’ range shifts on phenology range shifts was significant in our model investigating the relationship between these responses, indicating that species shifting their northern range limits to higher latitudes also showed stronger advances in their emergence phenology (Figure 3).” (Lines 341-344).

As there were no significant effects in the model of phenology change drivers, we have not shown results of this model: “Emergence phenology shifts were not affected by species’ traits, range geography, nor climate variability; due to this, model results are not displayed here.” (Lines 383-384).

Comment:

(46) Table 2: L712-713: What does this mean? Are phenology shifts not used as a predictor of range shifts? (why then this comment?). Or do you want to say phenological shifts are not related to Southern range etc? Why do you present a phylosig here but not in Table 1? Why not include the traits as predictors (from the range shift models) in these models as well? Consider using the range size as a continuous predictor instead of 'Widespread'.

We are glad the reviewer pointed this out to us. We did not emphasize this issue sufficiently. We DID evaluate traits as predictors both of geographical range and phenological shifts, and species-specific biological traits did not significantly affect models predicting either of those sets of responses. We state this on Lines 312-323, but we have also noted in the discussion (Lines 473-476) that the most commonly assessed traits, like body size, do not alter observed trends here. Instead, where species are found, rather than the characteristics of species, is the key determinant of their overall responses.

Following this excellent suggestion, we re-analysed our data using range size, calculated as the number of quadrats occupied by a species in the historical time period, as a predictor. Range size was not significant in our models, but we believe this is the best way to analyze our data, and so have updated our methods (Lines 261-263) and results (375-378).

Comment:

(47) Figure 1: I don't see any grey points in the figure. Also, there is no A or B. If you are referring to the symbols then write cross and triangle instead and not use capital letters which usually refer to component plots of composite figures. Also, I highly recommend providing a similar figure based on your data (maybe each species as a dot for T1 and another symbol for T2). Given the small number of species, you could try to connect these points with arrows. For the set with only range shifts maybe play the T2-dots at the center of the 'Emergence' axis.

Thank you for pointing out this error: a previous version of Figure 1 included grey points and multiple panels. We have removed this text from the figure caption to be consistent with the final version of the figure (Line 989).

The graphical depictions of the conceptual and empirical discoveries in this paper were challenging to create. The reviewer might be suggesting effectively decomposing Figure 3 (change in range on the y axis vs change in phenology among all species into two sets of points on the same graph, where each pair of points is a before and after value for each species. This would make for a very busy figure indeed. We have modified the conceptual Figure 1 to illustrate more clearly, we believe, that species can (in principle) remain within tolerable niche spaces by shifting their activity periods in time (phenology) or in space (geographical range) or both.

Comment:

(48) Figure 2: Please add a legend. Also black is a poor background color. The maps appear to be stretched. Please check aspect ratios. Now here are capital letters without an explanation in the caption. From the context I assume the upper panel maps are for the data used to calculate range shifts at the bottom panel maps are for data used to calculate the phenological shifts.

We apologise for the error in the figure caption and have clarified the differences between panels in the text, as well as changing the map background colour and fixing the aspect ratio:

“Figure 2: Richness of 76 odonate species sampled in North America and Europe in the historic period (1980-2002; panes A and C) and the recent period (2008-2018; panes B and D). Species richness per 100 × 100 km quadrat is shown in panes A and B, while panes C and D show species richness per 200 × 200 km quadrat. Dark red indicates high species richness, while light pink indicates low species richness.” (Lines 1002-1006).

Comment:

(49) Figure 3: Why this citation? Of terrestrial taxa? Please explain. Consider adding some stats here, such as the r-squared value for each of the relationships.

We have better explained the citation in the figure caption, as well as adding r-squared values:

“Figure 3: Relationship between range shifts and emergence phenology shifts among North American and European odonate species (N = 66; model R2 = 17.08 for glm, 14.9% for MCMCglmm). For reference, the shaded area shows mean latitudinal range shifts of terrestrial taxa as reported by Lenoir et al. (2020; calculated as the yearly mean dispersal rate of 1.11 +/- 0.96 km per year over 38 years).” (Lines 679-682)

Comment:

(50) L801: What are these underscored references?

This was an issue with the reference software and has been resolved.

Comment:

(51) Table S1: L848: Consider starting with 'Samples of 76 North American and European odonate species from between ...'. Please use a horizontal line to separate the content from the table header. Add a horizontal line below the last row. Same for all tables.

Thank you for this suggestion, we have edited the caption for Figure S1 as suggested (Line 1124). We have also made the suggested line additions to Table S1, S2, and S3.

Comment:

(52) Table S3: This is confusing. In Table 1 (main text) both 'southern range' and 'widespread' are used as predictors. Please explain.

We originally included information on species range geography, including southern versus northern range, and widespread versus not, into one categorical variable. Following additional comments we re-analysed our data using range size, calculated as the number of quadrats occupied by a species in the historical time period, as a predictor. Now the methods section text (Lines 261-263) and Table 1 report results of that variable with distribution options northern, southern, or both.

Comment:

(53) Figure S5 and S6: It would be more coherent if the colors refer to the continents and the suborders are indicated by shading. I would love to see a combination of the two figures with species ordered by the phylogenetic relationship and a dot matrix indicating the traits in the main text! This could really be a good starting point for a synthesis figure.

The reviewer presents an interesting challenge for us. We have a choice, as we understand things, to present a figure showing phylogeny and traits (as requested here), or an ordered list of species relative to effect sizes in the two main responses to global change. The latter choice centers on the discoveries of the paper, while the former would be valuable for dragonfly biology but would depict information that proved to be biologically uninformative relative to our discovery. That is to say, there is no phylogenetic trend and biological traits among species did not affect results. We have gone some way toward illustrating that issue by retaining phylogeny in the MCMC-GLMM models, but we feel that a figure illustrating phylogeny and traits would (for most readers, at least) illustrate noise, rather than signal. For this reason, we have opted to take on the previous reviewer’s suggestion for a modified, main-text Figure 4, which we include below.

Figure 4: Distribution of Northern range limit shifts (Panel A, kilometers) and emergence phenology shift (Panel B, Julian day) of 76 European and North American odonate species between a recent time period (2008 - 2018) and a historical time period (1980 - 2002). Anisoptera (dragonflies) are shown in pink, Zygoptera (damselflies) are shown in blue.

Change last: Figure 3: Relationship between range shifts and emergence phenology shifts among North American and European odonate species (N = 66; model R2 = 17.08 for glm, 14.9% for MCMCglmm). For reference, the shaded area shows mean latitudinal range shifts of terrestrial taxa as reported by Lenoir et al. (2020; calculated as the yearly mean dispersal rate of 1.11 +/- 0.96 km per year over 38 years).

RRID:SCR_009550

DOI: 10.1038/s41398-025-03508-y

Resource: Connectivity Toolbox (RRID:SCR_009550)

Curator: @scibot

SciCrunch record: RRID:SCR_009550

Besides, potential biotechnological uses of haloarchaeal pigments are poorly explored. This work summarises what it has been described so far about carotenoids from haloarchaea and their production at mid- and large-scale, paying special attention to the most recent findings on the potential uses of haloarchaeal pigments in biomedicine.

Además, los posibles usos biotecnológicos de los pigmentos haloarqueales están poco explorados. Este trabajo resume lo descrito hasta la fecha sobre los carotenoides de las haloarqueas y su producción a mediana y gran escala, con especial atención a los hallazgos más recientes sobre los posibles usos de los pigmentos haloarqueales en biomedicina.

sin embargo, su intensa adhesión a los sentimientos de la teoría del dominó lo llevaron a él y a su administración a comprometer un apoyo intenso e inquebrantable a un inestable Vietnam del Sur, plantando las semillas para un eventual conflicto en Vietnam, uno en el que Estados Unidos podría verse obligado a participar.

Evidencia que el gobierno estadounidense busca contener la influencia comunista sobre la población a toda costa, aunque esta política tenga costos sobre los financiamientos de la administración.

RRID: CVCL_1544

DOI: 10.1186/s12885-025-14621-y

Resource: (KCLB Cat# 90226, RRID:CVCL_1544)

Curator: @dhovakimyan1

SciCrunch record: RRID:CVCL_1544

RRID: CVCL_0609

DOI: 10.1186/s12885-025-14621-y

Resource: (ATCC Cat# HTB-55, RRID:CVCL_0609)

Curator: @dhovakimyan1

SciCrunch record: RRID:CVCL_0609

RRID:CVCL_0168

DOI: 10.1186/s12885-025-14621-y

Resource: (BCRJ Cat# 0395, RRID:CVCL_0168)

Curator: @scibot

SciCrunch record: RRID:CVCL_0168

RRID:CVCL_1535

DOI: 10.1186/s12885-025-14621-y

Resource: (BCRJ Cat# 0271, RRID:CVCL_1535)

Curator: @scibot

SciCrunch record: RRID:CVCL_1535

RRID:CVCL_1511

DOI: 10.1186/s12885-025-14621-y

Resource: (RRID:CVCL_1511)

Curator: @scibot

SciCrunch record: RRID:CVCL_1511

RRID:AB_881220

DOI: 10.1186/s12885-025-14621-y

Resource: None

Curator: @scibot

SciCrunch record: RRID:AB_881220

RRID:AB_3697464

DOI: 10.1186/s12885-025-14621-y

Resource: None

Curator: @scibot

SciCrunch record: RRID:AB_3697464

RRID:CVCL_B260

DOI: 10.1186/s12885-025-14621-y

Resource: (BCRJ Cat# 0331, RRID:CVCL_B260)

Curator: @scibot

SciCrunch record: RRID:CVCL_B260

RRID:AB_3064850

DOI: 10.1186/s12885-025-14621-y

Resource: None

Curator: @scibot

SciCrunch record: RRID:AB_3064850

RRID:CVCL_0042

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-61500-y

Resource: (RRID:CVCL_0042)

Curator: @scibot

SciCrunch record: RRID:CVCL_0042

# def is also used to create named functions def add(x, y) do x + y end

As per the above explanation, Everything returns a value in Elixir, isn't the def a statement just as in Python in the above example

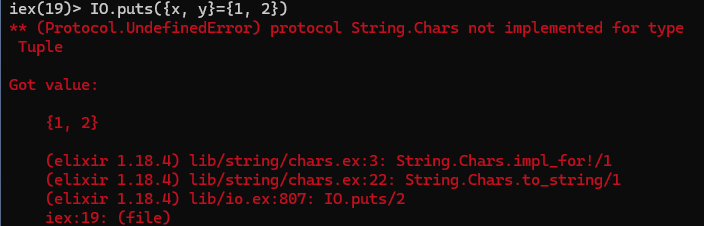

IO.puts({x, y} = {1, 2})

I got an undefined error

Formate para liderar los roles que están revolucionando el futuro del trabajo:

Falta agregar el área de Sostenibilidad y ESG

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors have studied the mechanics of bolalipid and archaeal mixed-lipid membranes via comprehensive molecular dynamics simulations. The Cooke-Deserno 3-bead-per-lipid model is extended to bolalipids with 6 bead. Phase diagrams, bending rigidity, mechanical stability of curved membranes, and cargo uptake are studied. Effects such as formation of U-shaped bolalipids, pore formation in highly curved regions, and changes in membrane rigidity are studied and discussed. The main aim has been to show how the mixture of bolalipids and regular bilayer lipids in archaeal membrane models enhances the fluidity and stability of these membranes.

The authors have presented a wide range of simulation results for different membrane conditions and conformations. Analyses and findings are presented clearly and concisely. Figures, supplementary information and movies are of very high quality and very well present what has been studied. The manuscript is well written and is easy to follow.

The authors have provided detailed response to the points I raised on the first version and have revised their manuscript accordingly. Hence, I only mention what, in my opinion, still deserves to be noted.

Comments:

I previously raised an issue with respect to the resort to the Hamm-Kozlov model for fitting the power spectrum of membrane undulations. The authors provided very nice arguments against my concerns. For the sake of completeness, I include a simple scenario, which will better highlight the issue:

The tilt contribution to the Helfrich Hamiltonian can be written as a quadratic term 1/2 k_t |T|^2, where T is a tilt vector field. This field is written as the difference between the surface normal and the director field aligned with the lipid orientations. In the small deviation Monge description with z=h(x, y) as the height function, the surface normal has the form N=(-dh/dx, -dh/dy, 1). Now assume the director field, n = (b_x, b_y, 1) with small b_x and b_y components. The tilt contribution to the energy thus reads as 1/2 k_t (N - n)^2 ~= 1/2 k_t [|grad h|^2 + 2 b . grad h]. The first term, 1/2 k_t |grad h|^2, is indeed similar to a surface tension term, \sigma |grad h|^2 that you get from the (1 + 1/2 |grad h|^2) approximation to the area element. Therefore, if you only look at height fluctuations, while your membrane actually has some surface tension, it will make distinguishing the tilt contributions to the fluctuations in the linear Monge gauge impossible.

However, considering that the authors have made sure that the membrane is indeed tensionless, this argument is settled.

I had also raised an issue about the correct NpT sampling in the simulations, and I'm glad that the authors also set up more rigorously thermostatted/barostatted simulations to check the validity of their findings.

Also, from the SI, I previously noted that the authors had neglected the longest wavelength mode because it was not equilibrated. This was an important problem and the authors looked into it and ran more simulations that were better equilibrated.

The analysis of energy of U-shaped lipids with the linear model E=c_0 + c_1 * k_bola is indeed very interesting. I am glad that the authors have expanded this analysis and included mean energy measurements.

Why, for example, does terrestrial life use only 20 of the scores of amino acids that can be produced

En este párrafo me llamó la atención esta pregunta y decidí indagar un poco. Según lo que investigué, pudo haber sido un proceso aleatorio, sin embargo, estos 20 aminoácidos fueron los que proporcionaron una base más solida para la vida, ya que, el código genético que traduce los genes en proteínas está limitados a estos 20 aminoácidos y habría tenido mayor dificultad si se hubieran incluido más; trayendo mutaciones fatales para la vida.

n 2021, the Hayabusa2 space mission successfully delivered a morsel of the asteroid 162173 Ryugu to Earth — five grams of the oldest, most pristine matter left over from the solar system’s formation 4.5 billion years ago. Last spring, scientists revealed that the chemical composition of the asteroid includes 10 amino acids, the building blocks of proteins. The discovery added to the evidence that the primordial soup from which life on Earth arose may have been seasoned with amino acids from pieces of asteroids.

esta investigación es que nos recuerda que la vida en la Tierra quizá no empezó únicamente aquí, sino que fue el resultado de una colaboración cósmica. Los rayos gamma, que normalmente asociamos con radiación peligrosa, en realidad pudieron ser la chispa que transformó simples moléculas en aminoácidos dentro de los asteroides. Es como si el universo mismo hubiera hecho una especie de laboratorio natural, preparando los ingredientes de la vida y enviándolos a nuestro planeta en forma de meteoritos.

El objetivo de este estudio fue describir las características pedagógicas en losprocesos evaluativos implementados en asignaturas virtuales en las Carreras deGrado en la Universidad Nacional de Villarrica del Espíritu Santo. Se analizaronen profundidad factores que caracterizan a una evaluación en un ambiente virtual,estrategias didácticas evaluativas, gestión de la evaluación y el seguimiento delestudiante. Se realizó un estudio de caso múltiple con enfoque mixto. Se observólas características evaluativas en las carreras de Licenciatura en Ciencias de laEducación e Ingeniería en Sistemas Informáticos. Los resultados muestran quelas evaluaciones implementadas son innovadoras y variadas, pero se identificaronalgunas limitaciones en cuanto a la claridad de los criterios de evaluación y lafrecuencia de retroalimentación individualizada. Estos hallazgos sugieren lanecesidad de fortalecer la formación docente en el diseño e implementación delas evaluaciones en ambientes virtuales

Necesito que realicen un resumen del siguiente texto

existen programas de posgrado (maestrías y doctorados) que aborden las humanidades digitales.

No existían para 2017, ya en 2025 hay algunas como es el caso de la que se imparte en la UAQuerétaro y en el Tec de Monterrey.

dweb.link@ http://bafybeihda4gloeygr5moflptlfedkbhkuysutw7ulbomreqfx6fywro4xa.ipfs.localhost:8080/?filename=%EF%BC%82display%20metaphor%20scripting%20language%EF%BC%82%20gyuri%20lajos%20dime%20-%20Brave%20Search%20(8_12_2025%209%EF%BC%9A35%EF%BC%9A01%20AM).html

for = wikify myself

CSP vs Actor model for concurrency -

Discussion on: CSP vs Actor model for concurrency

my comment on this

BDSC:59958

DOI: 10.1093/genetics/iyaf151

Resource: RRID:BDSC_59958

Curator: @scibot

SciCrunch record: RRID:BDSC_59958

Aunque los biocombustibles suelen considerarse una opción ecológica, su producción a partir de cultivos agrícolas provoca más daños que beneficios: favorece la deforestación, incrementa las emisiones de CO₂ de manera indirecta, encarece los alimentos y amenaza a los ecosistemas. Solo tendrían un verdadero valor sustentable si se elaboran con residuos o mediante tecnologías que no compitan con la agricultura ni demanden grandes extensiones de tierra.

Communication

Est-ce qu'il y a moyen que le bas du tableau soit enligné avec ceux de gauche? (voir les flèches ou venir me voir si mon commentaire n'est pas claire)

Formation financière

Est-ce qu'il y a moyen que le bas du tableau soit enligné avec ceux de gauche et droite? (voir les flèches ou venir me voir si mon commentaire n'est pas claire)

Financial Training

Est-ce qu'il y a moyen que le bas du tableau soit enligné avec ceux de gauche et droite? (voir les flèches ou venir me voir si mon commentaire n'est pas claire)

y 1 sc * v 1 ; P{TRiP.HMC05965}attP40

DOI: 10.1083/jcb.201709026

Resource: RRID:BDSC_65150

Curator: @maulamb

SciCrunch record: RRID:BDSC_65150

Reproducible analysis

Me da la impresión que este debiera ser el objetivo fuerte a impulsar dentro del ecosistema de la ciencia abierta. Digo, sobre el que más trabajo falta por hacer. Se podrían citar los ejercicios de replicación de Breznau. No necesariamente acá, sino más adelante al momento de habalr sobre el caso de Chile y latinoamérica.

However, like many others developments in science, the open science movementhas arrived slowly to Latin America, especially in social sciences. Although there have been some initiativesin recent years, most of them are driven mainly by the natural sciences.

Acá sería bueno señalar que en términos generales, la mayoría de los logros en ciencias sociales en América Latina se concentran en el crecimiento de fuentes y publicaciones abiertas como Scielo o Redalyc: https://www.ouvrirlascience.fr/latin-america-could-become-a-world-leader-in-non-commercial-open-science/

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

In this study by Li et al., the authors re-investigated the role of cDC1 for atherosclerosis progression using the ApoE model. First, the authors confirmed the accumulation of cDC1 in atherosclerotic lesions in mice and humans. Then, in order to examine the functional relevance of this cell type, the authors developed a new mouse model to selectively target cDC1. Specifically, they inserted the Cre recombinase directly after the start codon of the endogenous XCR1 gene, thereby avoiding off-target activity. Following validation of this model, the authors crossed it with ApoE-deficient mice and found a striking reduction of aortic lesions (numbers and size) following a high-fat diet. The authors further characterized the impact of cDC1 depletion on lesional T cells and their activation state. Also, they provide in-depth transcriptomic analyses of lesional in comparison to splenic and nodal cDC1. These results imply cellular interactions between lesion T cells and cDC1. Finally, the authors show that the chemokine XCL1, which is produced by activated CD8 T cells (and NK cells), plays a key role in the interaction with XCR1-expressing cDC1 and particularly in the atherosclerotic disease progression.<br /> Strengths:

The surprising results on XCL1 represent a very important gain in knowledge. The role of cDC1 is clarified with a new genetic mouse model.

Thank you

Weaknesses:

My criticism is limited to the analysis of the scRNAseq data of the cDC1. I think it would be important to match these data with published data sets on cDC1. In particular, the data set by Sophie Janssen's group on splenic cDC1 might be helpful here (PMID: 37172103; https://www.single-cell.be/spleen_cDC_homeostatic_maturation/datasets/cdc1). It would be good to assign a cluster based on the categories used there (early/late, immature/mature, at least for splenic DC).

Thank you very much for your help. Using the scRNA seq data of Xcr1<sup>+</sup> cDC1 sorted from ApoE<sup>–/–</sup> mice, we re-annotated the populations, following the methodology proposed by Sophie Janssen's group. These results are presented in Figure S9 and Figure S10 and described in detail in the Results and Discussion section.

Please refer to the Results section from line 264 to 284: “Using the scRNA seq data of Xcr1<sup>+</sup> cDC1 sorted from hyperlipidemic mice, we annotated the 10 populations as shown in Figure S9A, following the methodology from a previous study [41]. Ccr7<sup>+</sup> mature cDC1s (Cluster 3, 7 and 9) and Ccr7- immature cDC1s (remaining clusters) were identified across cDC1 cells sorted from aorta, spleen and lymph nodes (Figure S9B). Further stratification based on marker genes reveals that Cluster 10 is the pre-cDC1, with high expression level of CD62L (Sell) and low expression level of CD8a (Figure S9C). Cluster 6 and 8 are the proliferating cDC1s, which express high level of cell cycling genes Stmn1 and Top2a (Figure S9D). Cluster 1 and 4 are early immature cDC1s, and cluster 2 and 5 are late immature cDC1s, according to the expression pattern of Itgae, Nr4a2 (Figure S9E). Cluster 9 cells are early mature cDC1s, with elevated expression of Cxcl9 and Cxcl10 (Figure S9F). Cluster 3 and 7 as late mature cDC1s, characterized by the expression of Cd63 and Fscn1 (Figure S9G). As shown in Figure 5C and Figure S9, the 10 populations displayed a major difference of aortic cDC1 cells that lack in pre-cDC1s (cluster 10) and mature cells (cluster 3, 7 and 9). Interestingly, in hyperlipidemic mice splenic cDC1 possess only Cluster 3 as the late mature cells while the lymph node cDC1 cells have two late mature populations namely Cluster 3 and Cluster 7. In further analysis, we also compared splenic cDC1 cells from HFD mice to those from ND mice. As shown in Figure S10, HFD appears to impact early immature cDC1-1 cells (Cluster 1) and increases the abundance of late immature cDC1 cells (Cluster 2 and 5), regardless of the fact that all 10 populations are present in two origins of samples. We also found that Tnfaip3 and Serinc3 are among the most upregulated genes, while Apol7c and Tifab are downregulated in splenic cDC1 cells sorted from HFD mice”.

Please refer to the Discussion section from line 380 to 385: “Based on the maturation analysis of the cDC1 scRNA seq data [41], our findings suggest that the aortic cDC1 cells display a major difference from those of spleen and lymph nodes by lacking the mature clusters, whereas lymph node cDC1 cells contain an additional Fabp5<sup>+</sup> S100a4<sup>+</sup> late mature Cluster. Our results also suggest that hyperlipidemia contributes to alteration in early immature cDC1 and in the abundance of late immature cDC1 cells, which was associated with dramatic change in gene expression of Tnfaip3, Serinc3, Apol7c and Tifab”.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

This study investigates the role of cDC1 in atherosclerosis progression using Xcr1Cre-Gfp Rosa26LSL-DTA ApoE-/- mice. The authors demonstrate that selective depletion of cDC1 reduces atherosclerotic lesions in hyperlipidemic mice. While cDC1 depletion did not alter macrophage populations, it suppressed T cell activation (both CD4+ and CD8+ subsets) within aortic plaques. Further, targeting the chemokine Xcl1 (ligand of Xcr1) effectively inhibits atherosclerosis. The manuscript is well-written, and the data are clearly presented. However, several points require clarification:

(1) In Figure 1C (upper plot), it is not clear what the Xcr1 single-positive region in the aortic root represents, or whether this is caused by unspecific staining. So I wonder whether Xcr1 single-positive staining can reliably represent cDC1. For accurate cDC1 gating in Figure 1E, Xcr1+CD11c+ co-staining should be used instead.

The observed false-positive signal in the wavy structures within immunofluorescence Figure 1C (upper panel) results from the strong autofluorescence of elastic fibers, a major vascular wall component (alongside collagen). This intrinsic property of elastic fibers is a well-documented confounder in immunofluorescence studies [A, B].

In contrast, immunohistochemistry (IHC) employs an enzymatic chromogenic reaction (HRP with DAB substrate) that generates a brown precipitate exclusively at antigen-antibody binding sites. Importantly, vascular elastic fibers lack endogenous enzymatic activity capable of catalyzing the DAB reaction, thereby preventing this source of false positivity in IHC.

Given that Xcr1 is exclusively expressed on conventional type 1 dendritic cells [C], and considering that IHC lacks the multiplexing capability inherent to immunofluorescence for antigen co-localization, single-positive Xcr1 staining reliably identifies cDC1s in IHC results.

[A] König, K et al. “Multiphoton autofluorescence imaging of intratissue elastic fibers.” Biomaterials vol. 26,5 (2005): 495-500. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.02.059

[B] Andreasson, Anne-Christine et al. “Confocal scanning laser microscopy measurements of atherosclerotic lesions in mice aorta. A fast evaluation method for volume determinations.” Atherosclerosis vol. 179,1 (2005): 35-42. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.10.040

[C] Dorner, Brigitte G et al. “Selective expression of the chemokine receptor XCR1 on cross-presenting dendritic cells determines cooperation with CD8+ T cells.” Immunity vol. 31,5 (2009): 823-33. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.027

(2) Figure 4D suggests that cDC1 depletion does not affect CD4+/CD8+ T cells. However, only the proportion of these subsets within total T cells is shown. To fully interpret effects, the authors should provide:

(a) Absolute numbers of total T cells in aortas.

(b) Absolute counts of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.