what is just in time learning: build an engagement engine This article helps professional developers strategize about the use of just in time learning. Some of the tips are unsurprising while others offer new ideas. It is a quick read and useful for ideas for professional developers. rating 5/5

- Mar 2019

-

www.growthengineering.co.uk www.growthengineering.co.uk

-

elearningindustry.com elearningindustry.com

-

10 awesome ways to use mobile learning for employee training This is an article about strategies and applications of mobile learning for employee development. A number of ideas are presented. I lack the knowledge base to evaluate the soundness, novelty, etc. of these ideas. There are screen shots and they are interesting enough but give only a limited idea of the concept being discussed. rating 3/5

-

-

www.talentlms.com www.talentlms.com

-

Using Just in Time Training for Active Learning in The Workplace

This does not necessarily seem to be of top quality but it is the only item I have found so far that addresses just in time training specifically within healthcare. It does not do so in great depth. It does briefly address technology and mobile learning but not in a way that is tremendously insightful. rating 2/2

-

-

www.efrontlearning.com www.efrontlearning.com

-

Time Training (and the Best Practices

What is just in time training This is an introductory and brief article that relates to just in time training. It describes the conditions needed to bring about adoption of this process. I am not in a position to evaluate the content but the ideas seem useful. rating 4/5

-

-

www.edsurge.com www.edsurge.com

-

This article explains just in time learning (such as that which can be done via devices) within the context of higher education. My interest is in public health education, but at this moment, I am not sure how much I can narrow in on that topic, so I will save this for now. This is obviously not a scholarly article but is of some interest nonetheless. rating 2/5

-

-

www.allisonrossett.com www.allisonrossett.com

-

This plain page incorporates an overview of job aids by Allison Rossett, who is the foremost authority on the topic. Not all information is given away for free as she wants to sell her books, which are also promoted on the page. This page can be a good way of tracking her current work. Rating 3/5

-

-

theamericanscholar.org theamericanscholar.org

-

In academia, an article that is 10 years old is considered dated.

In academia - but Lasch is still considered relevant?

-

The more recent the research is, the better—or at least, more relevant—it’s assumed to be.

The more recent the better

-

In a field such as technology, in which time does not march so much as it whizzes by, the freshness test is understandable.

-

Society does not change overnight, but thinking it does lends a sense of drama to our everyday lives.

Drama is more important that reality?

-

- Feb 2019

-

static1.squarespace.com static1.squarespace.com

-

she did not advocate extensive reading. She wanted her program to be within the reach of every woman-

I'm thinking this is also a nod at the time women had/didn't have because of the various duties they had to fulfill. Also maybe a nod at the fact that women would probably not really have a space/place in which they could extensively read. Yes?

-

-

www.graphgrid.com www.graphgrid.com

- Jan 2019

-

static1.squarespace.com static1.squarespace.com

-

nature—as opposed to cul-ture—is ahistorical and timeless?

Doreen Massey has an interesting book that touches on this (Space, Place, and Gender), where she points out that time and space are treated as binaries, where time is typically masculine and dynamic and space is feminine and static. Nature (gendered feminine) is spatial, a place, and therefore not a time ("ahistorical and timeless"). Culture, on the other hand, is temporal, dynamic, masculine. It's a very particular rhetoric which begs the "which one?" question.

(While Massey points out this common way of conceiving of time/space and binaries in general [A vs. Not A], she argues that the concept of space needs to be defined on its own merit, distinct from its binary opposite.)

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

static1.squarespace.com static1.squarespace.com

-

waxedand waned

Similar to the phases of the moon. Represents time passing.

-

-

iphysresearch.github.io iphysresearch.github.io

-

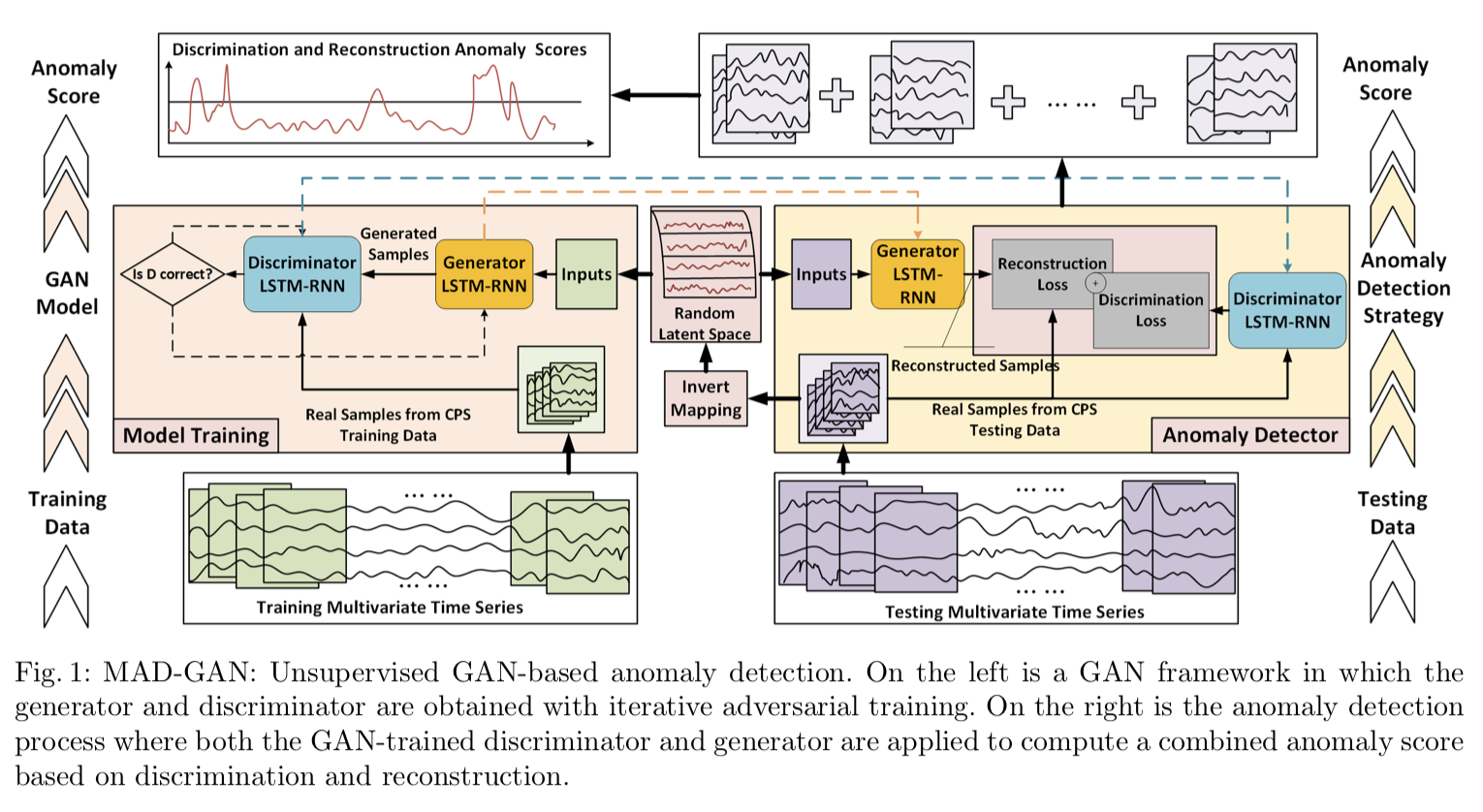

MAD-GAN: Multivariate Anomaly Detection for Time Series Data with Generative Adversarial Networks

这 paper 挺神的,用 GAN 做时序数据异常检测。主要神在 G 和 D 都仅用 LSTM-RNN 来构造的!不仅因此值得我关注,更因为该模型可以为自己思考“非模板引力波探测”带来启发!

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

Cross-cultural disaster research may also provide further insights regarding disaster phases.

Evokes feminist, critical and post-colonial theory, as well as multi- and inter-disciplinary research methods/perspectives, e.g., anthropology, etc.

These points of view may also provide insights on how disaster phases interact with wholly different notions of social time.

-

As the field of collective behavior highlights, individuals in social settings have different perceptions of reality-social settings are not homogeneous (e.g., Turner and Killian I 987).' Thus, to tap further the mutually inclusive, multidimensional and social-time aspects of disaster phases, researchers should draw upon multiple publics and their definition of disaster phases.

Neal suggests avoiding the disaster phase terminology when interviewing various stakeholders (emergency mgt, disaster-affected people, government agencies) in order to "draw upon various groups' language to describe phases" instead of the National Governors Assn phases.

-

Consid� e�g the redefinition of disaster phases based on social time may help us WJtb the broader and more important struggle of defining disaster.

What happened with this call to arms? Did Neal or others in the emergency management research community follow up?

http://ijmed.org/articles/624/download/ <-- Neal's 2013 paper on "Social Time and Disaster"

-

Consid� e�g the redefinition of disaster phases based on social time may help us WJtb the broader and more important struggle of defining disaster

Neal wrote a more recent 2013 paper discussing the topic of social time and disaster.

-

D!saster and hazard researchers have recognized the social time aspect of disasters. Dynes_ (1970) alludes to social time regarding the social consequences of a disaster. Dynes observes that social time: is important because the activities of every community vary over a period of time duri�� �e day, the week, the month, and the year. S�c� patterned acuv1nes have implications for potential damage within thecommurnty, for preventative activity within the commu�ty, for the inventory of the meaning of the disaster, for the rmm�?1ate tasks necessary within the community, and for the mobilizanon of community effort. (Dynes 1970, p. 63)

As early as 1970 (pre-Zerubavel, Adam, Nowotny, and Giddens), Dynes suggested that social time be taken into account for disaster response.

** Get this paper. What social time work did he cite?

-

The Phases Should Reflect Social Rather Than Objective Time Giddens (I 987), although not the first, makes an important theoretical distinction between social and objective time. Giddens defines clock time as the use of quantified units. Clock time represents "day-to-day" structured activities. Typically, studies refer to disaster phases with hours, days, weeks, or years. Social time, however, is contingent upon the needs or opportunities of a society.

Cites Giddens here to describe differences between social time (sturcturation) and clock time.

-

Stoddard argues that the use of time-and-space models in disaster research

Complete quote runs over 2 pages: "Stoddard argues that the use of time-and-space models in disaster research provides an important methodological disaster research tool. Most important, he contends that the different phases of disaster represent different types of individual and group behavior."

Stoddard's definition offers a solid framework to begin the conversation about how and why it's important to understand the interaction between pluritemporal modes of time and humanitarian response (individual and group sensemaking and enactment).

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

The fact that information produced by discretionary decision making cannotbe conveyed anonymously has important implications for CSCW systems design.Naturally, such information must be accompanied by the identity of the source.But how to represent and present the identity of the source?

This dilemma also applies to the complexity of representing time in information systems.

-

At the level of the objects themselves, shareabilitymay not be a problem, but in terms of their interpretation, the actors must attempt tojointly construct a common information space which goes beyond their individualpersonal information spaces. A nice example of how this is a problem has been givenby Savage (1987, p. 6): ‘each functional department has its own set of meaningsfor key terms. [...] Key terms such aspart, project, subassembly, toleranceareunderstood differently in different parts of the company.’

This would be good to explore with SBTF in the interviews. Particularly, whether there are different meanings to time modes, time meta data, etc., applied by Core Team, Coordinators, GIS Team, experienced volunteers, new volunteers, etc.

Is this part of the problem with articulating the information extracted from social media and entering it in the Google Sheet in order to become an artifact?

-

- Dec 2018

-

inst-fs-iad-prod.inscloudgate.net inst-fs-iad-prod.inscloudgate.net

-

Recording accurate and consistent time is often a challenge. Web log fi les record many different timestamps during a search interaction: the time the query was sent from the client, the time it was received by the server, the time results were returned from the server, and the time results were received on the client. Server data is more robust but includes unknown network latencies. In both cases the researcher needs to normalize times and synchronize times across multiple machines. It is common to divide the log data up into “days,” but what counts as a day? Is it all the data from midnight to midnight at some common time reference point or is it all the data from midnight to midnight in the user’s local time zone? Is it important to know if people behave differently in the morning than in the evening? Then local time is important. Is it important to know everything that is happening at a given time? Then all the records should be converted to a common time zone.

Challenges of using time-based log data are similar to difficulties in the SBTF time study using Slack transcripts, social media, and Google Sheets

-

Two common ways to partition log data are by time and by user. Partitioning by time is interesting because log data often contains signifi cant temporal features, such as periodicities (including consistent daily, weekly, and yearly patterns) and spikes in behavior during important events. It is often possible to get an up-to-the- minute picture of how people are behaving with a system from log data by compar-ing past and current behavior.

Bookmarked for time reference.

Mentions challenges of accounting for time zones in log data.

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

The Indeterminacy of the Past: Multiple Times, Multiple Voices The third methodological theme concerns ihe f1asl as indetc,rr,1inate. 10 We are constantly revising our knowledge of the past in light of new developments in the present.

Visibility can be obtained by peeling back the history of the infrastructure -- how it began, how it was added to, how it changed/adapted over time.

Looking back in time also provides an opportunity to consider how different people/perspectives influenced the infrastructure. Who was vocal? Who was silent? Who was silenced?

-

Classifications may or may not become standardized. If they do not, they are ad hoc, limited to an individual or a local community, and/or of Limited duration. At the same time, every successful standard imposes a classification system, al the very least between good and bad ways of organizing acLions or things. And the work-arounds involved in the practical use of standards frequently entail the use of ad hoc nonstandard categories.

This is an important point for classifying and standardizing modes of time and temporal representations in information systems. What comes first? The class or the standard?

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

Classifications may or may not become standardized. If they do not, they are ad hoc, limited to an individual or a local community, and/or of limited duration. At the same time, every successful standard imposes a classification system, at the very least between good and bad ways of organizing actions or things. And the work-arounds involved in the practical use of standards frequently entail the use of ad hoc nonstandard categories.

This is an important point for classifying and standardizing modes of time and temporal representations in information systems. What comes first? The class or the standard?

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

In particular, concurrency control problems arise when the software, data,and interface are distributed over several computers. Time delays when ex-changing potentially conflicting actions are especially worrisome. ... Ifconcurrency control is not established, people may invoke conflicting ac-tions. As a result, the group may become confused because displays are incon-sistent, and the groupware document corrupted due to events being handledout of order. (p. 207)

This passage helps to explain the emphasis in CSCW papers on time/duration as a system design concern for workflow coordination (milliseconds between MTurk hits) versus time/representation considerations for system design

-

eople prefer to know who else is present in a shared space, and they usethis awareness to guide their work

Awareness, disclosure, and privacy concerns are key cognitive/perception needs to integrate into technologies. Social media and CMCs struggle with this knife edge a lot.

It's also seems to be a big factor in SBTF social coordination that leads to over-compensating and pluritemporal loading of interactions between volunteers.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

iphysresearch.github.io iphysresearch.github.io

-

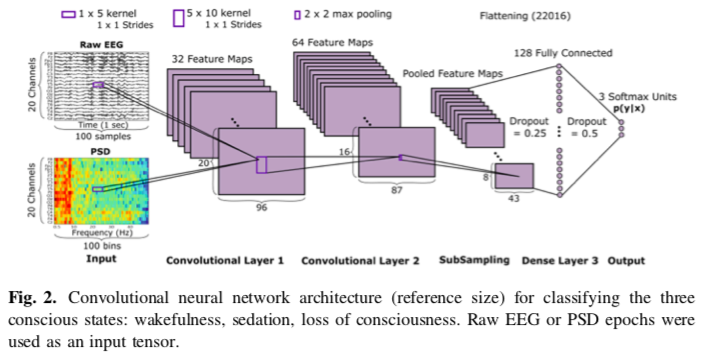

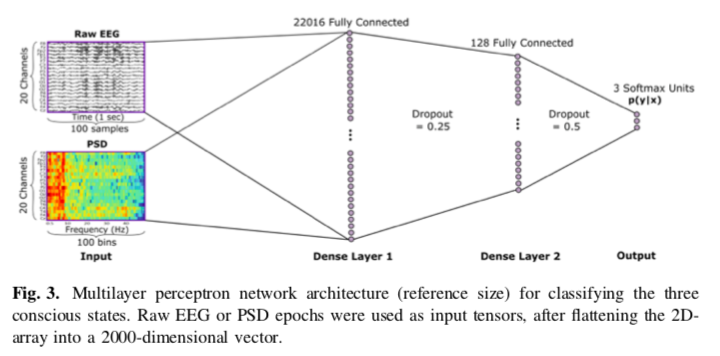

Deep Neural Networks for Automatic Classification of Anesthetic-Induced Unconsciousness

spatio-temporo-spectral features.

-

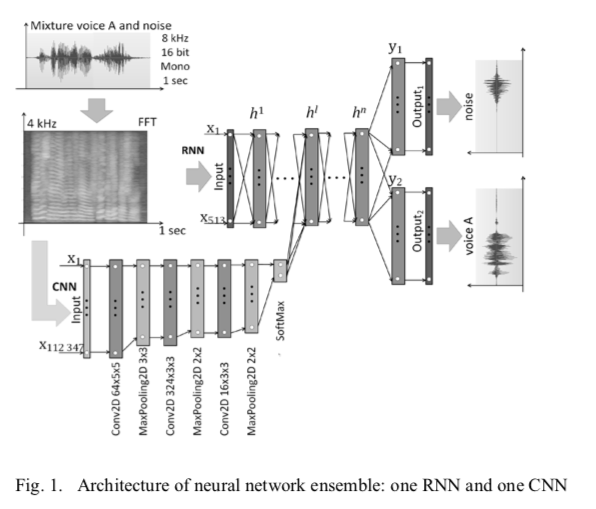

Using Convolutional Neural Networks to Classify Audio Signal in Noisy Sound Scenes

先辨别信号位置,再过滤出信号,这和 LIGO 找event波形的套路很像~ ;又看到 RNN与CNN 结合起来的应用~

-

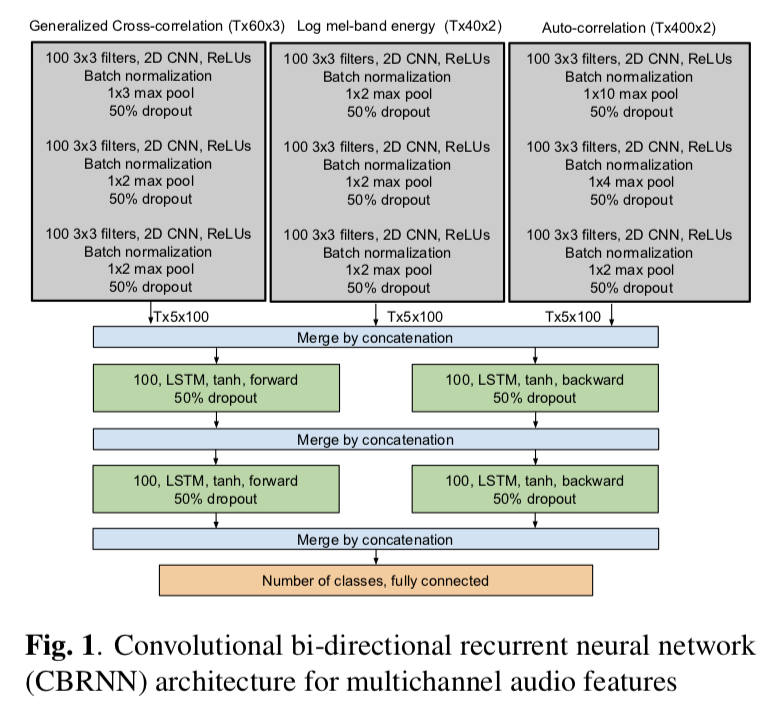

Sound Event Detection Using Spatial Features and Convolutional Recurrent Neural Network.

输入数据是多通道音频信号,网络是结合了CNN 和 LSTM。

-

-

www.gutenberg.org www.gutenberg.org

-

nail-adorned jewels she gave to the heroes:

She is well-respected within the mead hall and in return respects the men of the hall

-

’Mid hall-building holders. The highly-famed queen, 55 Peace-tie of peoples, oft passed through the building, Cheered the young troopers; she oft tendered a hero A beautiful ring-band, ere she went to her sitting

Wealhtheow portrays the role of a traditional Anglo-Saxon woman at the time. Wealhtheow is first introduced to the audience, she immediately falls into her role as peaceful greeter and cocktail waitress. The author then reinforces that she is a member of the weaker gender by directing Wealhtheow to her proper position behind the king. When the queen is not serving drinks or greeting the hall guests, she may usually be found obediently following Hrothgar throughout the mead hall and "waiting for hope-news".

-

-

shinelikethunder.tumblr.com shinelikethunder.tumblr.com

-

This may be a personal itch, but at least for personal archiving needs, I’m sick, sick, sick of the recency bias that’s eaten the internet since the first stirrings of Web 2.0. Wikis are practically the only sites that have escaped chronological organization. It would be cool to have easily-manipulated collections with non-kludgey support for series ordering, order-by-popularity, order-by-popularity with a manual bump for posts you want to highlight, hell even alphabetical ordering. None of these things are remotely unsolved problems, but they’re poorly supported on the social-media silos most people’s content lives on these days.

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

- Video Url with start time information.

-

- Nov 2018

-

iphysresearch.github.io iphysresearch.github.io

-

Multilevel Wavelet Decomposition Network for Interpretable Time Series Analysis

初步扫了一眼,感觉这篇文章应该可以给我一些 idea,内含我感兴趣(看得懂)的方法/机制,另外综述的参考文献对我来时也应该很有帮助。

本文是北京航空航天大学发表于KDD 2018的文章,作者提出了将小波变换和深度神经网络进行完美结合,克服了融合的损失,对时间序列数据的分析起到了很好的启发性研究。

Summary

-

Foundations of Sequence-to-Sequence Modeling for Time Series

利用序列到序列模型来做时序数据预测的理论研究 paper~

-

Interpretable Convolutional Filters with SincNet

一篇值得我高度关注的 paper,来自 AI 三巨头之一 Yoshua Bengio!其背后的核心是将数字信号处理DSP中卷积的激励函数(滤波器)进行了重新设计,不仅会保留了卷积的特性(线性性+时间平移不变性)还在滤波器上添加待学习参数来学习合适的高低频截断位置。

-

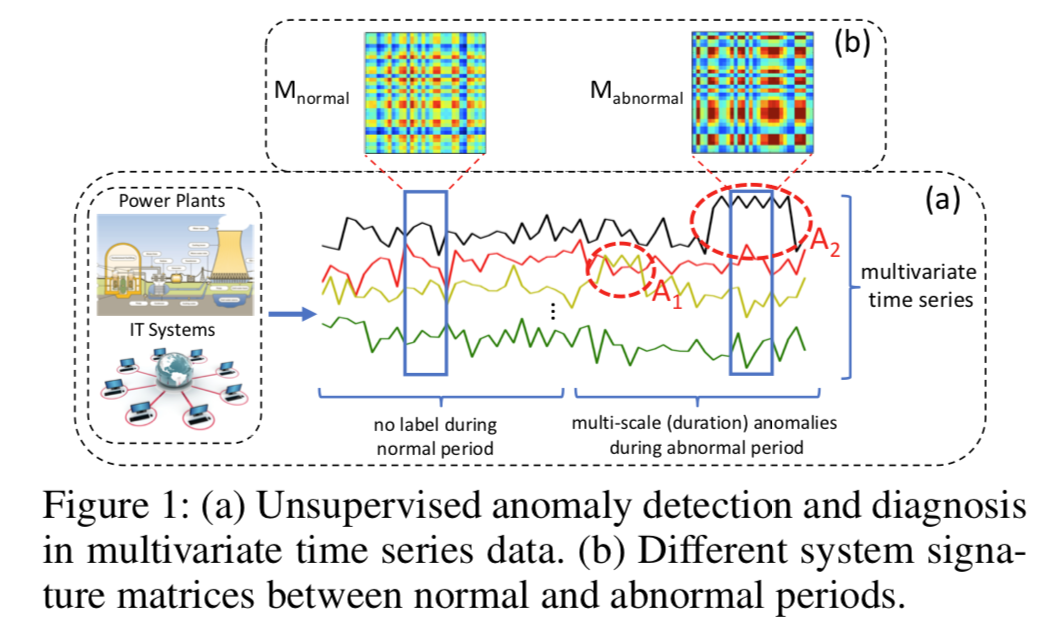

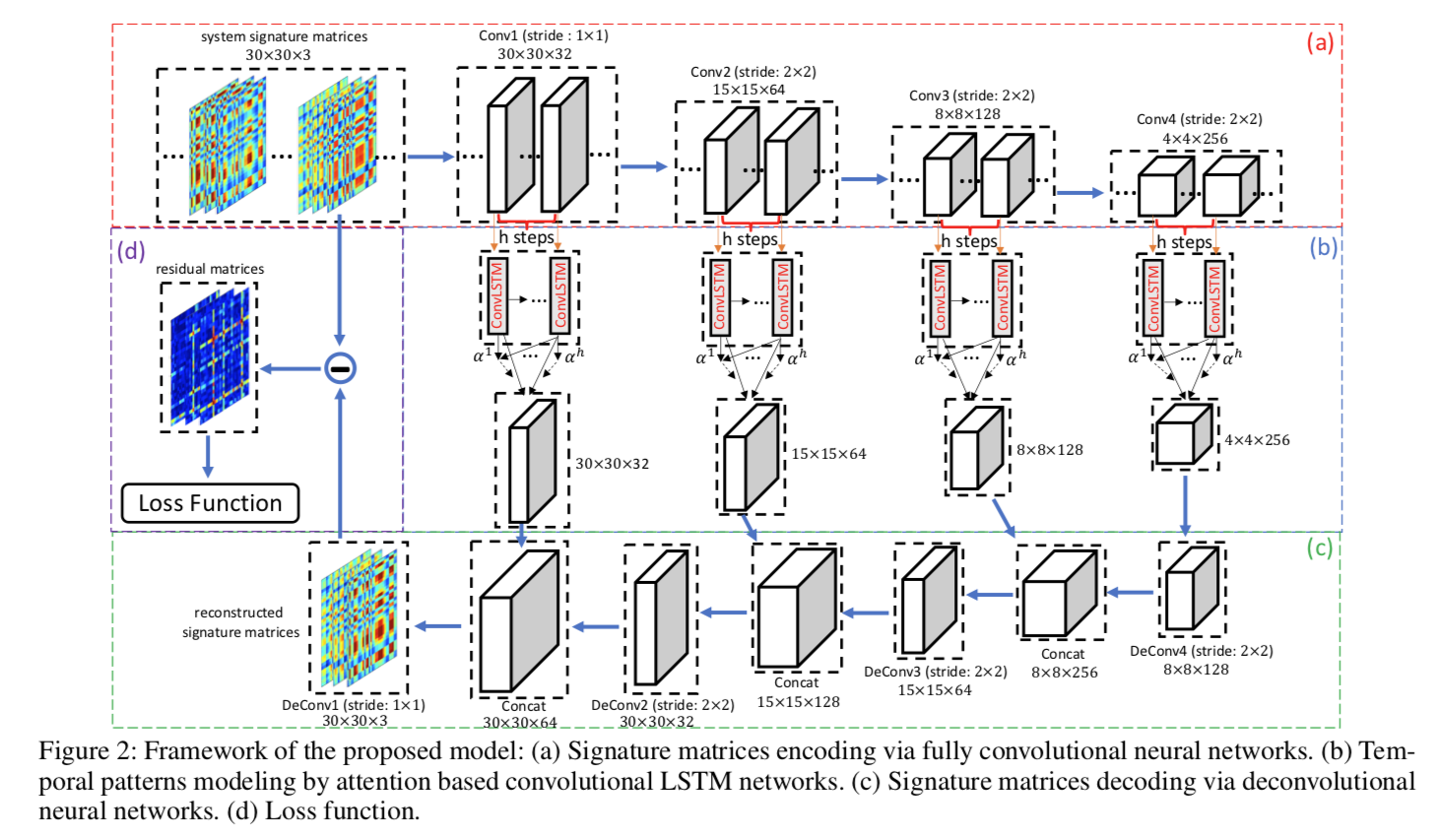

A Deep Neural Network for Unsupervised Anomaly Detection and Diagnosis in Multivariate Time Series Data

虽然数据特点为多变量时序信号+噪声少还频率低,不过作者提出的 Multi-Scale Convolutional Recurrent Encoder-Decoder (MSCRED) 网络很有趣,可见基于注意力机制的 ConvLSTM 在模式识别上是大为有用的!

此外paper里的数学表述和实验讨论也很值得参考学习,算是非常标准的基于新model的 paper 样板~

-

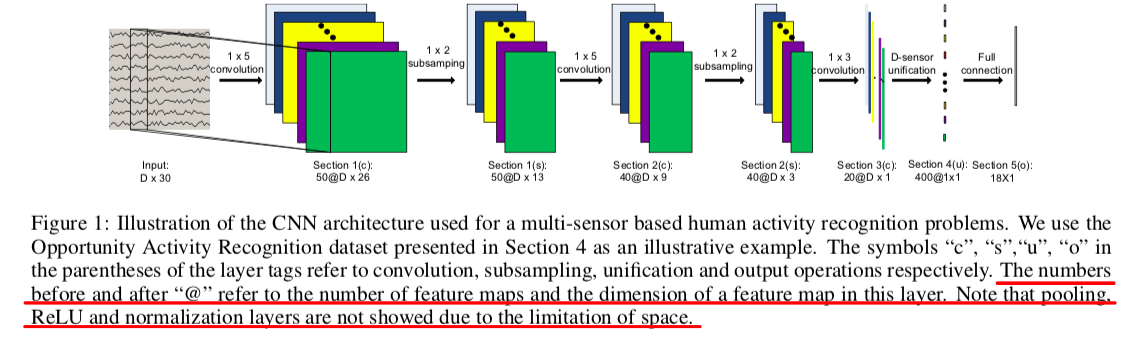

Deep Convolutional Neural Networks On Multichannel Time Series For Human Activity Recognition.

这个文章的研究对象是 HAR 问题。不过这里的多通道时序信号是排成 长 x 宽维度,模拟图片数据来解决的,并不是图像的多通道。不过最后的效果貌似很不错,远胜过 SVM,KNN,MV,以及 DBN(深度置信网络)。

文章对网络结构的英文描述还是值得借鉴的~

-

Towards a universal neural network encoder for time series

数据任务是“时序序列的分类”,这是我感兴趣的问题。Universal 代表不需要额外设置和训练,从某数据集训练后,就可以拿到另一个新训练集类型去搞事情~ 另一个特点是用了 encoder 得到了低维不变的表示。

-

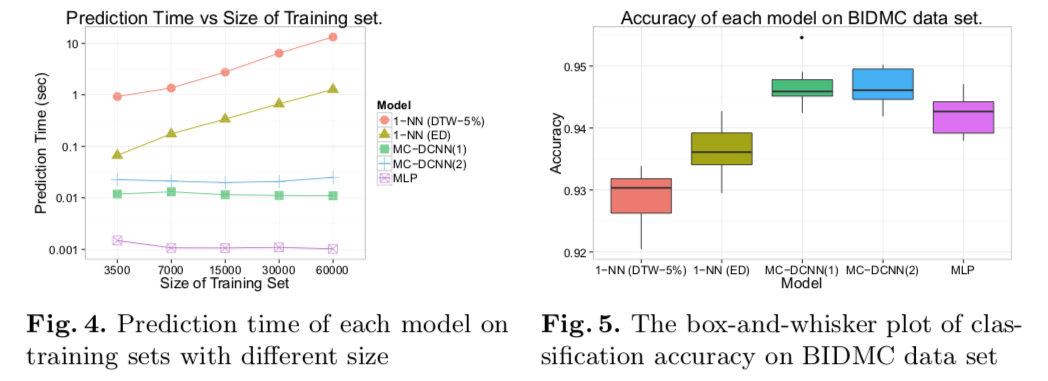

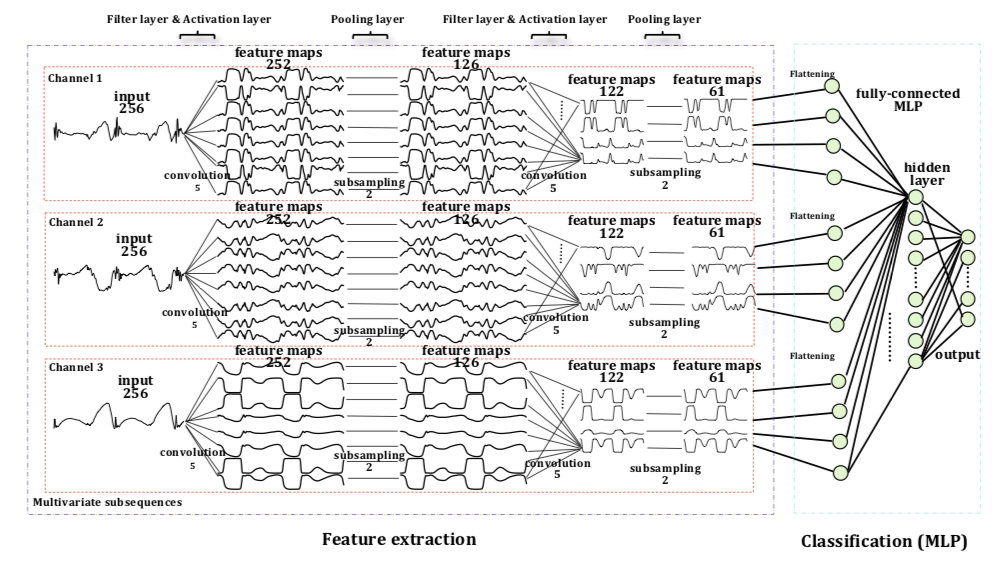

Time Series Classification Using Multi-Channels Deep Convolutional Neural Networks

这是一个三通道并列输入的时序信号模型。效果貌似不错,还针对不同模型算法的预测时间在不同训练规模数据上的模型表现做了对比,

另外文章的模型图示也很有启发性。

-

Stochastic Adaptive Neural Architecture Search for Keyword Spotting

一篇讲 identifying keywords in a real-time audio stream 的 paper。这和引力波探测中的数据处理很接近哦~!此文提出 end-end 的“随机自适应神经构架搜寻” (SANAS) 实现高效准确的训练效果。这显然对 real-time 特点的类型数据应用带来启发。FYI:人家源码还开放了。。。

-

WaveGlow: A Flow-based Generative Network for Speech Synthesis

一篇来自 NVIDIA 的小文。提出的实时生成网络 WaveGlow 结合了 Glow 和 WaveNet 的特点,实现了更快速高效准确的语音合成。

-

Deep learning for time series classification: a review

这个文与我的课题貌似相当相关!

准备好好写一个 Paper Summary 为好~

-

Deep Learning for Time-Series Analysis

一个比较简洁的关于时序序列的 DL 应用的综述文章。

其中也有谈论时序序列的分类问题。

-

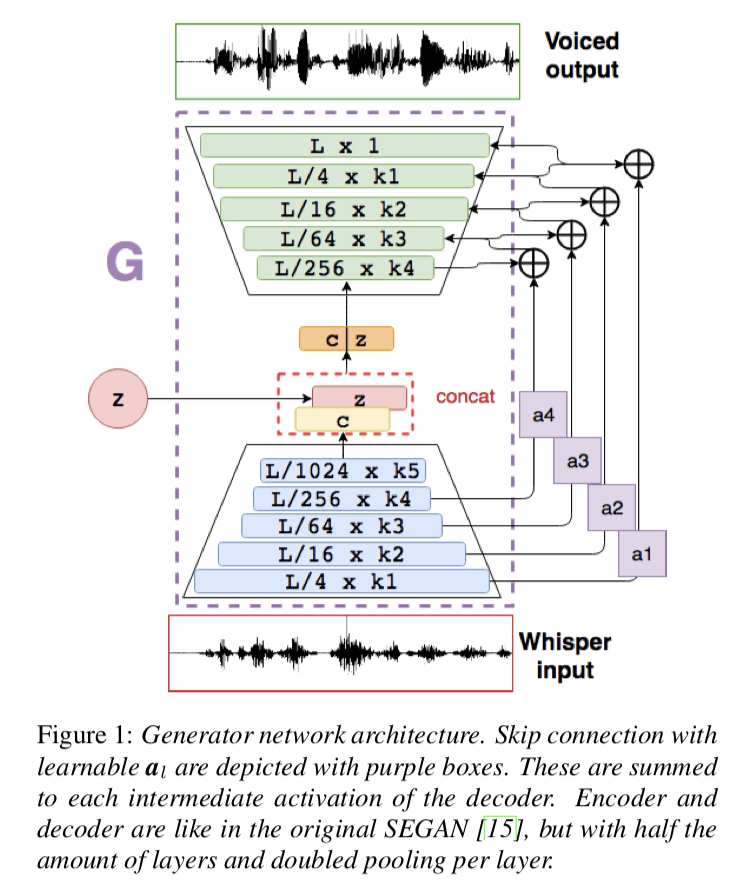

Whispered-to-voiced Alaryngeal Speech Conversion with Generative Adversarial Networks

这是一篇用 GAN 来做 Voiced Speech Restoration 的,并且使用了作者自己提出的 speech enhancement using GANs (SEGAN) 。

于我而言,亮点有二:

- 数据是时序语音

- 利用 GAN 对语音的增强效果似乎对降噪有些启发

- 网络结构图画的蛮好看的:

-

Model Selection Techniques -- An Overview

一篇关于模型选择的综述文章。涉及信号处理,图像处理等等多方面数据信息的处理。发表在信号处理的期刊杂志上。

文中关于模型选择的大概念方向,和数学表示,是值得好好阅读的。

-

End-to-end music source separation: is it possible in the waveform domain?

讨论的是 Music source separation 问题。

作者认为前人基于spectrogram的输入数据都忽略了相位信息,所以提出了直接waveform-based的模型得到了明显更好的效果。

-

Unifying Probabilistic Models for Time-Frequency Analysis

文章涉及好些自己还没搞懂的概念和方法:

- 时频分析

- Gaussian processes

- ...

文中的 review 给的是很不错的~

-

-

jolt.merlot.org jolt.merlot.org

-

Early Attrition among First Time eLearners: A Review of Factors that Contribute to Drop-out, Withdrawal and Non-completion Rates of Adult Learners undertaking eLearning Programmes

NEW - This study researches dropout rates in eLearning. There are many reasons for attrition with adult eLearners which can be complex and entwined. The researched provide different models to test and also a list of barriers to eLearning - where technology issues ranked first. In conclusion, the authors determined that further research was necessary to continue to identify the factors that contribute to adult learner attrition.

RATING: 7/10

-

-

www.surveymonkey.com www.surveymonkey.com

-

SurveyMonkey

SurveyMonkey is a FREE survey platform that allows for the collection of responses from targeted individuals that can be easily collected and used to create reports and quantify results. SurveyMonkey can be delivered via email, mobile, chat, web and social media. The platform is easy to use and can be used as an add on for large CRMs such as Salesforce. There are over 100 templates and the ability to develop customized templates to suit your needs. www.surveymonkey.com

RATING: 5/5 (rating based upon a score system 1 to 5, 1= lowest 5=highest in terms of content, veracity, easiness of use etc.)

-

-

www.mojet.net www.mojet.net

-

Using WikitoTeach Part-Time Adult Learners in aBlended learningEnvironment

Using Wiki

-

- Oct 2018

-

homes.cs.washington.edu homes.cs.washington.edu

-

iving in the Past, Present, andFuture: Measuring TemporalOrientation With Language

Messages were rated on their temporal distance from the present, with 0 representing current moments, negative values representing the past and positive values denoting the future. • Extraversion positively associated with future & negatively with the past • Openness negatively with the past • Conscientiousness negatively with the present, pos with others • Agreeableness negatively with the present, pos w future • Life satisfaction present neg future pos • Neuroticism none • Depression present pos, future neg

-

-

www.citylab.com www.citylab.com

-

digitalpedagogy.mla.hcommons.org digitalpedagogy.mla.hcommons.org

-

http://www.zachwhalen.net/posts/how-to-make-a-twitter-bot-with-google-spreadsheets-version-04

useful for automating tweets?

-

-

chrome.google.com chrome.google.com

-

arxiv.org arxiv.org

-

-

timetravel.mementoweb.org timetravel.mementoweb.org

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

tools.ietf.org tools.ietf.org

-

The HTTP-based Memento framework bridges the present and past Web. It facilitates obtaining representations of prior states of a given resource by introducing datetime negotiation and TimeMaps. Datetime negotiation is a variation on content negotiation that leverages the given resource's URI and a user agent's preferred datetime. TimeMaps are lists that enumerate URIs of resources that encapsulate prior states of the given resource. The framework also facilitates recognizing a resource that encapsulates a frozen prior state of another resource.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

- Aug 2018

-

www.fastcompany.com www.fastcompany.com

-

When you interrupt a task, it can be difficult to pick it up again.

yes, because people who always have inertia.

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

The notion of temporal structuring views "real time" not as an inherent property of Internetbased activities, or an inevitable consequence of technology use, but as an enacted temporal structure, reflecting the decisions people have made about how they wish to structure their activities, both on or off the Internet. As an alternative to the idea of '·real time," Bennett and Wei II ( 1997) have suggested the notion of "real-enough time," proposing that people design their process and technology infrastructures to accommodate variable timing demands, which are contingent on task and context. We believe such "real-enough" temporal structures are important areas of further empirical investigation, allowing us to move beyond the fixation on a singular, objective "real time" to recognize the opportunities people have to (re)shape the range of temporal structures that shape their lives.

real time vs real-enough time

-

The notion of temporal structuring focuses attention on what people actually do temporally in their practices, and how in such ongoing and situated activity they shape and are shaped by particular temporal structures. By examining when people do what they do in their practices, we can identify what temporal structures shape and are shaped (often concurrently) by members of a community; how these interact; whether they are interrelated, overlapping, and nested, or separate and distinct; and the extent to which they are compatible, complementary, or contradictory.

Different interaction patterns of temporal structures that are shaped by people and shape people's activities.

-

Viewed from a practice perspective, the distinction between cyclic and linear time blurs because it depends on the observer's point of view and moment of observation. In particular cases, simply shifting the observer's vantage point (e.g., from the corporate suite to the factory floor) or changing the period of observation (e.g., from a week to a year) may make either the cyclic or the linear aspect of ongoing practices more salient.

Could it be that SBTF volunteers are situating themselves in time as a way to respond to a cyclic/linear tension? or a spatial tension?

-

An emphasis on the cyclic temporality of organizational life also underpins the work on entrainment, developed in the natural sciences and gaining currency in organization studies. Defined as "the adjustment of the pace or cycle of one activity to match or synchronize with that of another" (Ancona and Chong 1996, p. 251 ), entrainment has been used to account for a variety of organizational phenomena displaying coordinated or synchronized temporal cycles (Ancona and Chong 1996, Clark 1990, Gersick 1994, McGrath 1990).

Entrainment definition.

-

In spite of the general movement from particular towards universal notions of time (Castells 1996, Giddens 1990, Zerubavel 1981 ), we can see that in use, all uni versa! temporal structures must be particularized to local contexts because they are enacted through the situated practices of specific community members in specific locations and time zones.

Cites Castells (networks), Giddens (structuration) and Zerubavel (semiotics) as moving away from particular time to more universal notions of real-time, 24-hour clock, and calendars, respectively.

Orlikowski and Yates argue that even universal notions need situated and contextual practices to make sense of time.

-

One such opposition is that between universal (global, standardized, acontextual) and particular (local, situated, contextspecific) time.

Orlikowski and Yates describe situated, contextual time as particular.

-

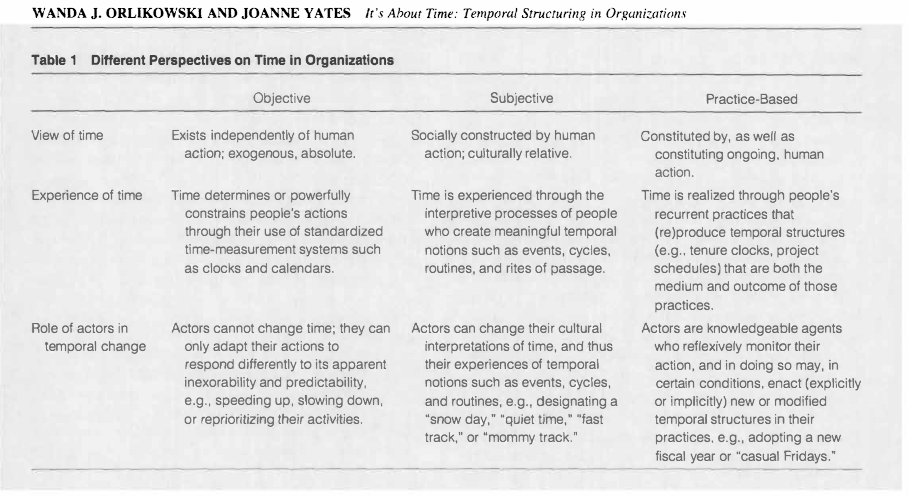

Table 1 Different Perspectives on Time in Organizations

Objective vs Subjective vs Practice-based perspectives in time

-

Event time, in contrast, is conceived as "qualitative time-heterogeneous, discontinuous, and unequivalent when different time periods are compared" (Starkey

Event time definition -- as qualitative.

How does this help describe friction of SBTF social coordination attempting to handle mechanical clocktime (timestamps, urgency, timelines, etc.) and dynamic event time (disaster unfolds, rhythms, horizons, etc.)

-

-

www.numbeo.com www.numbeo.com

-

30.40

30.40

-

-

www.numbeo.com www.numbeo.com

-

34.46

34.46

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.numbeo.com www.numbeo.com

-

36.64

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.numbeo.com www.numbeo.com

-

39.60

39.60

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.numbeo.com www.numbeo.com

-

36.17

36.17

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.numbeo.com www.numbeo.com

-

36.17 Moderate

36.17

-

-

www.numbeo.com www.numbeo.com

-

Time Index (in minutes): 43.85

43.85

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.numbeo.com www.numbeo.com

-

43.85 Moderate

43.85

-

-

www.numbeo.com www.numbeo.com

-

44.00 Moderate

44

-

-

www.numbeo.com www.numbeo.com

-

Traffic Commute Time Index 15.00 Very Low

15

-

-

www.numbeo.com www.numbeo.com

-

21.96

21.96

-

-

www.numbeo.com www.numbeo.com

-

Time Index (in minutes): 40.30

40.30

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

The haunting question is how do I fit into the story.

Need to read the football club paper to understand this context but is it referring to situating oneself in the story?

Read the Nâslund and Pemer paper to see how they are using the term "semantic fit".

-

Maclean et al. also demonstrate clearly how sensemaking can be defined by its stages. The movement through time of different forms of interpretive work is captured in their phrase ‘language that constructs and gives order to reality, which it (temporarily) sta-bilizes’ (p. 20). They suggest that this movement consists of locating, meaning-making, and becoming.

Maclean et al's definition of sensemaking

The idea of temporal stages and spatial movement that includes locating could also be a way to describe the situating behavior.

So far, this is the only definition that seems to include a temporal-spatial component

-

Later in their article, Cunliffe and Coupland effectively summarize sensemaking as embodied efforts to figure out what to do and who we are. That is a tidy framework for interpreting the life stories of elite bankers since they are essentially figuring out what they did and who they were, with heavy editing, to point up the legitimacy of the what and who that are retrieved.

Another Cunliffe and Coupland definition of sensemaking

Could "embodied efforts to figure out what to do and who we are" touch on what I'm calling situated time? Need to read the paper to see how they refer to the term embodied.

-

Gephart et al. define sensemaking as ‘an ongoing process that creates an intersubjective sense of shared meanings through conversation and non-verbal behavior in face to face settings where people seek to/produce, negotiate, and maintain a shared sense of meaning’ (2010: 284–285).

Gephart's definition of sensemaking

Could "shared meaning" be driving the need for SBTF volunteers to situate themselves in time in order to co-construct a story?

-

Cunliffe and Coupland treat sensemaking as ‘collaborative activity used to create, legitimate and sustain organiza-tional practices or leadership roles’ (p. 65). If we add the phrase ‘and individual’ to the word ‘collaborative’ in that definition then we have a rendition of sensemaking that works for the Maclean et al. article, right down to the focus on legitimacy and leadership.

Cunliffe and Coupland's definition of sensemaking

This seems less relevant to the SBTF volunteers' situating behavior.

-

Whittle and Mueller also anticipate and inform the nature of reconstructing a life story when they depict sensemaking as ‘a broader term [than stories] that refers to the process through which people interpret themselves and the world around them through the pro-duction of meaning’ (p. 114). It is their focus on ‘meaning’ and their inclusion of both the person and ‘the world around them’ that fits Maclean

Whittle and Mueller's definition of sensemaking

Could "process through which people interpret themselves and the world around them through the production of meaning" be driving the need for SBTF volunteers to situate themselves in time in order to co-construct a story?

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

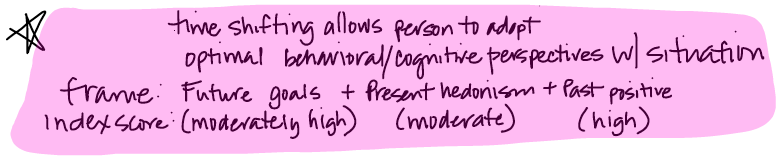

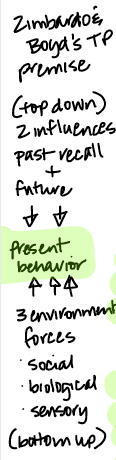

Second, howtime is variously used in past constructions that givesense to what has occurred, in for example, nostal-gic tales that seek to sustain identity-relevant valuesand beliefs, or using time to leverage reformulationsin repositioning these tales, for example, with theaim of undermining nostalgia as a platform for resis-tance (see Brown and Humphreys 2002; Strangleman1999).

Future research direction: Importance of reflexivity // Effects of Time Perspectives on sensemaking

See: Zimbardo & Boyd's Time Perspectives

-

As Bojeet al. (2016a, p. 395)indicate, through situating antenarratives in subjec-tive time, they are able to show ‘how diverse voicesinterconnect, embed and entangle in organizationalstrategies’.

Need to unpack this a bit. Is this how to scaffold the SBTF situated time instances into a sensemaking process?

Subjective time (per the philosopher's term) is referred to as socially-constructed time (by the sociologists).

In Brunelle (2017):

*"temporal construals

The way organizational members interpret or situate themselves in time and embrace time-related concepts such as of time scarcity, urgency, orientation. ‘temporal construals inform and are informed by intersubjective, subjective and objective times.’ (R. A. Roe et al., 2009)"*

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

Theway organizational membersinterpret or situate themselves in time and embrace time-related concepts such as of time scarcity, urgency, orientation. ‘temporal construals inform and are informed by intersubjective, subjective and objective times.’ (R. A. Roe et al., 2009

Get Roe's paper. This helps to bridge the ideas of "situated time" and "subjective time" -- or socially constructed ways of experiencing, thinking about and perceiving time.

See: Dawson and Sykes 2018 See: Pöppel 1978 - https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-46354-9_23

-

-

emlis.pair.com emlis.pair.com

-

There is also a need for mechanisms to support transformations and processesover time, both for scientific data and scientific ideas. These mechanisms should not only help the user visualize but also express time and change.

This is still true today. Is the problem truly a technical one or an opportunity to re-imagine the human process of representing time as an attribute and time as a function of evolving data?

-

Time as order considers temporal data as data that can be described by a time attribute, which can improve navigation or organization. Time as change considers temporal data as data that evolve over time.

The contrast of time as representing either order or change could be a very helpful way to categorize messy, dynamic humanitarian crisis data.

We need ways to capture data as an event timeline (X happened, then Y which demands response Z) as well acknowledge that X and Y may be in flux in an evolving crisis zone.

-

Temporal Data and Data Temporality: Time is change, not only ord

Synthesis:

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

These same requirements exist in distributed computing, in which tasks need to be scheduled so that they can be completed in the correct sequence and in a timely manner, with data being transferred between computing elements appropriately.

time factors in crowd work include speed, scheduling, and sequencing

-

-

www.numbeo.com www.numbeo.com

-

Dissatisfaction to Spend Time in the City12.30 Very Low

12.30

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

Nature has been incorporated into social theorizing only in as far as it either has become an object to which meaning is attributed and which hence figures as part of human reflexivity, as object met with emotions or attitudes; or, it is seen as an object of transformation by those forces which act upon it: economic forces, but foremost forces emanating from science and technology. The natural environment, including the biosphere and a multitude of environmental risks which have come to the fore today, negate clear-cut boundaries between the effects of human intervention, and hence agency, and synergistic processes which are 'natural' but still a result of human interaction with the environment. Time, it has been emphasized, is not only embedded in symbolic meaning or intersubjective social relations but also in artifacts, in natural and in culturally made ones. Likewise, the ongoing transformation and endangering of the natural environment is performed by processes which are chemical and atmospheric, biological and physical. But they all interact with social processes tied to energy production and use, modes of food production and land utilization, demographic pressures and possible interferences through use of tech-nology.

Nowotny seems to share Adam's concern about extracting nature and natural time from social constructions of time.

Perhaps this is a good place to embed the study's disaster event temporality as a way to further make sense of DHN social coordination and actions/reactions of disaster-affected people?

-

Social identities have increasing difficulty in being construed in terms of stable social attributes in a highly mobile -both socially and geographically - society. They will have to rely on other, temporal dimensions, in what are becoming increasingly precari-ous, if not completely contingent, identities in constant need of redefi-nition. One's 'own', proper time situated in a momentous present which is extended on the societal level in order to accommodate the pressing overload of problems, choices and strategies, becomes a central value for the individual as well as a characteristic of the societal system (Nowotny, 1989a)

I'm curious how this idea of mobility creates a precarious, contingent identity which forces people to use other temporal dimensions to situate themselves.

This could be an interesting way to approach the situated time phenomena I'm seeing in the SBTF study.

-

Major societal transformations are linked to information and communication technologies, giving rise to processes of growing global interdependence. They in turn generate the approxi-mation of coevalness, the illusion of simultaneity by being able to link instantly people and places around the globe. Many other processes are also accelerated. Speed and mobility are thus gaining in momentum, leading in turn to further speeding up processes that interlink the move-ment of people, information, ideas and goods.

Evokes Virilio theories and social/political critiques on speed/compression, as cited by Adam (2004).

Also Hassan's work, also cited by Adam (2004).

-

ut it will also have to come to terms with confronting 'the Other' (Fabian, 1983), with 'the curious asymmetry' still prevailing as a result of advanced industrial societies receiving a mainly endogenous and synchronic analytic treatment, while 'developing' societies are often seen in exogenous, diachronic terms. Study of 'Time and the Other' presupposes, often implicitly, that the Other lives in another time, or at least on a different time-scale. And indeed, when looking at the integrative but also potentially divisive 'timing' facilitated by modern communication and information-processing technology, is it not correct to say that new divisions, on a temporal scale, are being created between those who have access to such devices and those who do not? Is not one part of humanity, despite globalization, in danger of being left behind, in a somewhat anachronistic age?

Nowotny argues that "the Other" (non-western, developing countries, Global South -- my words, not hers) is presumed to be on a different time scale than industrial societies. Different "cultural variations and how societal experience shapes the construction of time and temporal reference..."

This has implications for ICT devices.

-

only structural functional theory, but all postfunctionalist 'successor' theories for their lack in taking up 'substantive' temporal issues, he was also pleading from the selective point of view of Third World countries for the exploration of theoretically possible alternatives or, to put it into other words, the delineation of what in the experience of western and non-western societies so far is universally valid and yet historically restric-ted. Such questions touch the very essence of the process of moderniz-ation. They evoke images of a closed past and an open or no longer so open future, of structures of collective memory as well as shifting collec-tive and individual identities of people who are increasingly drawn into the processes of world-wide integration and globalization. Anthropologi-cal accounts are extremely rich in different time reckoning modes and systems, in the pluritemporalism that prevailed in pre-industrialized societies. The theory of historical time - or times - both from a western and non-western point of view still has to be written. There exists already an impressive corpus of writings analysing the rise of the new dominant 'western' concept of time and especially its links with the process of industrialization. The temporal representations underlying the different disciplines in the social sciences allow not only for a reconceptualization of their division of intellectual labour, but also for a programmatic view forward towards a 'science of multiple times' (Grossin, 1989). However, any such endeavour has to come to terms also with non-western temporal experience.

Evokes Adam's critique of colonialization of time, commodification/post-industrial views, and need for post-colonial temporal studies.

-

Time' and time research is not ·an institutionalized subfield or subspeciality of any of the social sciences. By its very nature, it is recalcitrantly transdisciplinary and refuses to be placed under the intellectual monopoly of any discipline. Nor is time sufficiently recognized as forming an integral dimension of any of the more permanent structural domains of social life which have led to their institutionalization as research fields. Although research grants can be obtained for 'temporal topics', they are much more likely to be judged as relevant when they are presented as part of an established research field, such as studies of working time being considered a legit-imate part of studies of working life or industrial relations.

Challenges of studying time and avoiding the false claim that is a neglected subject.

-

The standardization of local times into standard world time is one of the prime examples for the push towards standardization and integration also on the temporal scale (Zerubavel, 1982).

Get this paper.

Zerubavel, E. (1982) 'The Standardization of Time: A Sociohistorical Perspective', American Journal of Sociology 1: 1-12.

-

At present, information and communication technologies con-tinue to reshape temporal experience and collective time consciousness (Nowotny, 1989b)

Get this paper.

Nowotny, H. (1989b) 'Mind, Technologies, and Collective Time Consciousness', in J. T. Fraser (ed.) Time and Mind, The Study of Time VI, pp. 197-216. Madison, CT: International Universities Press.

-

Despite the apparent diversity of themes, certain common patterns can be discerned in empirical studies dealing with time. They bear the imprint of the ups and downs of research fashions as well as the waxing and waning of influences from neighbouring disciplines. But they all acknowledge 'time as a problem' in 'time-compact' societies (Lenntorp, 1978), imbued with the pressures of time that come from time being a scarce resource.

Overview of interdisciplinary, empirical time/temporality studies from late 70s to 80s. (contemporary to this book)

Cites Carey "The Case of the Telegraph" -- "impact of the telegraph on the standardization of time"

Cites Bluedorn -- "it is omnipresent indecision-making, deadlines andother aspects of organizational behaviour like various forms of group processes"

-

Studies of time in organizations have long since recognized the importance of 'events' as a complex admixture which shapes social life inside an organiz-ation and its relationship to the outside world. 'Sociological analyses', we are told, 'require a theory of time which recognizes that time is a socially constructed, organizing device by which one set, or trajectory of events is used as a point of reference for understanding, anticipating and attempting to control other sets of events. Time is in the events and events are defined by organizational members' (Clark, 1985:36).

Review how this idea about events in organizations as a way to study time is used by Bluedorn, Mazmanian, Orlikowski, and/or Lindley.

-

The tension between action theory (or the theory of structuration) and sys-tems theory has not completely vanished, but at least the areas of dis-agreement have become clearer. The 'event' structure of time with its implicit legitimization through physics, but which is equally a central notion for historians (Grossin, 1989) holds a certain attraction for empiri-cal studies and for those who are interested in the definitional

Nowotny revisits Elias' idea about the relationship between time and events as a framework that is multidisciplinary, complex, integral to sensemaking, and appeals to empirical research.

-

The formation of time con epts and the making of time I measurements, i.e. the production of devices as well as their use and social function, become for him a problem of social knowledge and its formation. It is couched in the long-term perspective of evolution of human societies. Knowledge about time is not knowledge about an invariant part or object of nature. Time is not a quality inherent in things, nor invariant across human societies.

Combine this with the notes on Norbert Elias above.

-

As Bergmann (1981), and more recently, Ltischer (1989) and Adam (1990) and before them Joas (1980, 1989) have shown, a radical change in perspective away from time as 'flow' or time as embedded in the intentionality of the actor, can already be found in the social philosophy of time by G. H. Mead (Mead, 1936, 1932/1959, 1964). His is also a theory in which it is not the actor and his/her motives, interests or the means-ends scheme which dominates, but where action is interpreted as event -moreover, an event which is both temporal and social in nature.

Nowotny revisits the earlier mention of Mead's premise that "time is embedded in the intentionality of the actor."

Come back to this.

-

Action is but the constant intervention of humans into the natural and social world of events. Giddens adds that he would also like to make clear the constitutive relation between time and action. 'I do not' he says, 'equate action with intentionality, but action starts always from an intentionally-oriented actor, who orients him/herself just as much in the past, as he/she tries to realize plans for the future. In this sense, I believe, action can only be analyzed, if one recognizes its embeddedness in the temporal dimension' (Kiessling, 1988:289).

Giddens' structuration theory accounts for how social action/practices over time and space.

Structuration theory = "the creation and reproduction of social systems that is based in the analysis of both structure and agents"

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Structuration_theory

Both Adam and Nowotny engage quite a bit with Gidden's structuration theory/time-space distanciation concept, though sociologists are quite critical of the theory. Why?

-

To show 'how the positioning of actors in contexts of interaction and the interlacing of those contexts themselves' relate to broader aspects of social systems, Giddens proposes that social theory should confront 'in a concrete rather than an abstractly philosophical way' the situatedness of interaction in time and space (Giddens, 1984:110)

further description of time-space distanciation

-

It may well be, as Edmond Wright has pointed out (personal communi-cation) that by leaving sui generis time to the physicists, i.e. by leaving it out of social theory altogether, there is the risk of losing sight of the 'real' temporal continuum which serves as standard reference for all other forms of times. It also impedes coming to terms with 'time embedded' in natural objects and technical artifacts, as Hagerstrand (1974, 1975, 1988) repeatedly emphasized.

Nowotny argues that social theory is reduced to a narrow, dualistic society vs nature perspective by focusing on symbolism in social time and failing to consider other (sui generis) types of time.

This is especially problematic when exploring how time is embedded in "natural objects and technical artifacts".

-

The fundamen-tal question for Giddens then becomes how social systems 'come to be stretched across time and space' (i.e. how they constitute their tempor-ality (Giddens, 1984).

Space-time distanciation theory.

See also: Adam - 1990 - Time for Social Theory

-

quite different and much more radical approach is followed by Niklas Luhmann, who proposes to replace the subject/ action scheme by a time/action scheme, thus eliminating the actors alto-gether and replacing them with expectations and attributions.

Luhmann is a social systems theorist, whose work is not widely adopted in the US for being too complex. His work was also criticized by Habermas.

Esoteric. Not worth mentioning in prelim response.

-

To introduce time into present-day social theory means at its core to redefine its relation to social action and subsequently to human agency. It is there that the central questions arise, where differences begin to matter between action theory, structuration theory and system theory with regard to time.

Nowotny outlines the basic friction points for updating the prevailing social theories.

-

he third strategy is the unen-cumbered embracing of pluritemporalism. With or without awareness that the concept of an absolute (Newtonian) physical time broke down irrevocably at the turn of this century and that a different kind of plurit-emporalism has also been spreading in the physical sciences (Prigogine and Stengers, 1988; Hawking, 1988; Adam, 1990), social theory is free to posit the existence of a plurality of times, including a plurality of social times. In most cases this amounts to a kind of 'theoretical agnosti-cism' with regard to physical time. Pluritemporalism allows for asserting the existence of social time next to physical ( or biological) time without going into differences of emergence, constitution or epistemological

Pluritemporalism (multiple types of time representations/symbols) recognizes that there is no hierarchy/order between different "modes" or "shapes" of time be they described as physical, social, etc.

-

Another strategy in dealing with sui generis time consists in juxtaposing clock time to the various forms of 'social time' and considers the latter as the more 'natural' ones, i.e. closer to subjective perceptions of time, or to the temporality that results from adaptations to seasons or other kinds of natural (biological, environmental) rhythm. This strategy, often couched also in terms of an opposition between 'linear' clock time and 'cyclical' time of natural and social rhythms devalues, or at least ques-tions, the temporality of formal organizations which rely heavily on clock time in fulfilling their coordinative and integrative and controlling functions (Young, 1988; Elchardus, 1988).

by contrasting social time (as a natural phenomenon) against clock time, allows for a more explicit perspective on linear time (clock) and social rhythms when examining social coordination.

-

Searching to reconcile Darwinian evolutionary theory with Einsteinian relativity theory and, especially, its reconceptualization of simultaneity, Mead followed Whitehead's lead in locating the origins of all structuration of time in the notion of the 'event': without the interruption of the flow of time by events, no temporal experience would be possible (Joas, 1980, 1989)

Mead used events as a unit of analysis in contrasting social time with sui generis time (all other unique times, natural, physical, etc.). This way, time can be still be viewed as a relationship between history/evolution (past) and events (past/present/future) and other temporal types.

"Time therefore structures itself through interaction and common temporal perspectives are rooted in a world constituted through practice."

-

Related to this encounter of the first kind, in which social theory meets the concept of time, is the question of the relationship between time in social systems with other forms of (physical, biological, 'natural') time or, as Elchardus calls it, 'sui generis time' (Elchardus, 1988).

According to Elchardus, the idea of a relationship between social time and other forms ("sui generis time") is also studied by Giddens and Luhmann.

Later in this passage, Nowotny writes: "Elchardus suggests defining the culturally induced temporality of systems when certain conditions (i.e. relative invariance and sequential order) are met. Time then becomes the concept used to interpret that temporality."

-

By clarifying the concept of time as a conceptual symbol of evolving complex relationships between continua of changes of various kinds, Elias opens the way for grounding the concept of time again in social terms. The power of choosing the symbols, of selecting which continua are to be used, be it by priests or scientists, also beconies amenable to social analysis. The social matrix becomes ready once more to house the natural world or our conception of it in terms of its own, symbol-creating and continuously evolving capacity. The question of human agency is solved in Norbert Elias's case by referring to the process of human evolution through which men and women are enabled to devise symbols of increasing power of abstraction which are 'more adequate to reality'.

Per Nowotny on Elias: thinking about time as a conceptual symbol it can more readily be described in social terms, it holds natural and social time together, and it accounts for human agency in creating symbols to understand time in practice and in the abstract.

-

Unless one learns to perceive human societies, living in a world of symbols of their own making, as emerging and developing within the larger non-human universe, one is unable to attack one of the most crucial aspects of the problem of time. For Elias it consists, stated very briefly, in how to reconcile the highly abstract nature of the concept of time with the strong compulsion its social use as a regulatory device exerts upon us in daily life. His answer: time is not a thing, but a relationship. For him the word time is a symbol for a relationship which a group of beings endowed with the capacity for memory and synthesis establishes between two or more continua of changes, one of which is used by them as a frame of reference or standard of measurement for the other.

Nowotny descrobes Norbert Elias' conception of social time not as a thing but a relationship between people and two more more continua of changes.

continua = multiple ways to sequentially evaluate something that changes over past, present and future states.

Requested the Elias book cited here.

-

A definition of social time, like the one I attempted myself in the early 1970s, according to which the term social time 'refers to the experience of inter-subjective time created through social interaction, both on the behavioural and symbolic plane' now calls for a much more encompassing and dynamic definition, taking into account also the plurality of social times (Nowotny, 1975:326)

Social time definition -- which incorporates notion of plural temporalities.

-

Martins draws a distinction between two criteria of temporalism and/or historicism. One he calls 'thematic tem-poralism', indicated by the degree to which temporal aspects of social life, diachronicity, etc., are taken seriously as themes for reflection of meta theoretical inquiry. The other criterion is the degree or level of 'substantive temporalism', the degree to which becoming, process or diachrony are viewed as ontological grounds for socio-cultural life or as methodologically prior to structural synchronic analysis or explanations.

Difference between "thematic temporalism" and "substantive temporalism."

Thematic = "issues of time, change and history being taken seriously as objects of study" Substantive = "issues of becoming, process and change viewed as essential features of social life which help explain social phenomena"

This book provides a better description:

-

There is also a widespread acknowledgement, especially in evidence in the empirical literature, of what I will call 'pluritemporalism'. This is an acknowledgement of the existence of a plurality of different modes of social time(s) which may exist side by side, and yet are to be distinguished from the time of physics or that of biology.

Pluritemporalism defintion.

-

The demise of structural-functionalism, he argues, has not brought about a substantial increment in the degree of temporalism and historicism in the theoretical constructs of general sociology, even though this was one of the major goals announced by the critics of functionalism, paramount to a meta-theoretical criterion of what an 'adequate' theory should con-sist of.

Contested area for early social theorists -- suggested that "temporalism" should be a criterion for future social theory as a successor to structural-functionalism.

Definition: Structural Functionalism is a sociological theory that attempts to explain why society functions the way it does by focusing on the relationships between the various macro-social institutions that make up society (e.g., government, law, education, religion, etc) and act as a complex system whose parts work together to promote solidarity and stability. Robert Merton was a proponent of structural-functionalism.

-

The question is, rather, why the repeated complaint about the neglect of time in social theory or in the social sciences in general?

Nowotny lists a number of possible reasons for inaccurate complaints that time has been neglected in social theory or it has not been taken seriously despite the large body of literature.

I would offer a simpler reason: The prior work is incredible dense, very abstract, and hard to relate to lived/social experience.

-

Sorokin and Merton in 1937, entitled 'Social Time: A Methodological and Functional Analysis' that some of the Durkheimian ideas were taken up again. This paper identified social time as qualitatively heterogeneous (e.g. holidays and market days), not quantitatively homogeneous as astronomical or physical time has it. Social time was seen as being divided into intervals that derive from collective social activities rather than being uniformly flowing. Local time systems, it was argued, function mainly in order to assure the coordination and synchronization of local activities which eventually become extended and integrated, thereby necessitating common time systems. The Durkheimian claim of the category of time being rooted in social activities, of time being socially constituted by virtue of the 'rhythm of social life' itself, buttressed by the analysis of the social functions it served, was a tacit rebuttal of Kant's a priori intuitions of time, space and causality.

Sorokin and Merton extended Durkheim's work and staked the claim that social time was qualitative, varied, rhythmic and useful for social coordination in contrast to Kant's philosophy of time, space and causality.

Kant in a nutshell: "In 1781, Immanuel Kant published the Critique of Pure Reason, one of the most influential works in the history of the philosophy of space and time. He describes time as an a priori notion that, together with other a priori notions such as space, allows us to comprehend sense experience. Kant denies that neither space or time are substance, entities in themselves, or learned by experience; he holds, rather, that both are elements of a systematic framework we use to structure our experience. Spatial measurements are used to quantify how far apart objects are, and temporal measurements are used to quantitatively compare the interval between (or duration of) events. Although space and time are held to be transcendentally ideal in this sense, they are also empirically real—that is, not mere illusions." via Wikipedia Philosophy of space and time

-

The claim to the existence of a concept of 'social time', distinct from other forms of time, was thus made early in the history of social thought. It continues to focus upon the claims of the peculiar nature of the 'social constitution' or the 'social construction' of time. These claims evidently put the category of 'social time' into the wider realm of 'symbolic time', a cultural phenomenon, the constitution of which has remained the object of inquiry of more disciplines than sociology alone, but which separates it from time in nature, embedded in things and artifacts.

Early work in social time focused on the social construction of time and symbolic/semiotic representations (see Zerubavel).

Sociology and other disciplines see time as "embedded in things and artifacts" apart from what Adam refers to as natural time.

-

In the then undeveloped sociology of knowledge, Durkheim held as the most general conclusion that it is the rhythm of social life which is the basis of the category of time itself (Durkheim, 1912:7). These obser-vations opened up important questions about the social origins and func-tions of the category of time and how social time can be distinguished and is distinct from astronomical time.

Early history of "social time" via Durkheim.

Tags

- compression

- philosophy

- speed

- structuration theory

- sensemaking

- natural time

- theory

- post-industrial

- sociotemporality

- linear time

- colonialization

- events

- situated

- pluritemporalism

- standard

- time as relationship

- social coordination

- time-space distanciation

- tempo

- temporal experience

- artifacts

- social theory

- social time

- clock time

- ICT

Annotators

URL

-

-

course-computational-literary-analysis.netlify.com course-computational-literary-analysis.netlify.com

-

A light fringe of snow lay like a cape on the shoulders of his overcoat and like toecaps on the toes of his goloshes; and, as the buttons of his overcoat slipped with a squeaking noise through the snow-stiffened frieze, a cold, fragrant air from out-of-doors escaped from crevices and folds.

Here we find yet another personification of air, which enwraps the story with subtle layers of movement and circulation. We could trace this pattern, and its effects on narrative time and narrative progress, through concordances and dispersion plots of "air" and any wind-related words.

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

I am proposing that we need to take on board the time-scales of our technologies if our theories are to become adequate to their subject matter: contemporary industrialised, science-based technological society. Giddens's concept of time-space distanciation might prove useful here despite its association with the storage capacity of information Time for Social Theory: Points of Departure 167 which makes the present application of the concept primarily past, rather than past and future orientated. There seems to be no reason why the concept of time-space distanciation, with its link to power, could not be exploited to theorise influences on the long-term future. Such an extension would allow us to understand the present as present past and present future, where each change affects the whole.

Adam revisits the need to incorporate technology and artifacts into sociotemporal theory.

She cites Giddens' time-space distanciation, a construct that describes how social systems stretch across time and space to "store" knowledge, material goods, and cultural traditions.

-

Contemporary thinkers from a wide range of fields arrived at an understanding that recognises the implication of our past in the present; in other words, that our personal and social history forms an ineradicable part of us. I can find no good reason why we should exlude our biological and cosmic past from the acceptance of this general principle.

Adam contests Gidden's perspective on time-scale because he does not integrate biological or cosmic evolution into the influence that personal and social history can have on how people experience the present through the past.

-

Bearing in mind the conceptual difficulties and limitations of the level approach, we can see that an understanding through levels achieves a number of things. It emphasises the complexity of time and imposes order on the multiple expressions. It prevents us from focusing on one or two aspects of time at the expense of others. In addition to the more obviously social components, it establishes the centrality of the physical, living, technological, and artefactual aspects of social time. It stresses and affirms connections and relationships. It brings to the surface both the continuities and the irreducible aspects of social time. It helps us to avoid confusing the time aspects of our social life with those of nature

Despite the limitations, Adam largely supports Mead's approach since it "emphasizes the complexity of time and imposes order on the multiple expressions" over other frameworks centered on time as a series of stages or experienced as dualities.

-

To Mead the past is irrevocable to the extent that events cannot be undone, thoughts not unthought, and knowledge not unknown. In this irrever-sible form, he contends, the past is unknowable since the intervening knowledge continuously changes the meaning of that past and relentlessly recreates and reformulates it into a new and different past. He argues this on the basis of the proposition that only emergence in the present has reality status. He does not accord the past and future such a status because they are real only with respect to their relation to the present. In Mead's thought the past changes with respect to our experiencing it in the present and the meaning we give to it. In contradistinction to the past, he conceptualises the reality of the present as changing with each emergence.

Adam describes Mead's conceptualization of past/present/future as fluid levels. Present experience constantly changes our understanding, meaning, and knowledge about the past and future.

Adam notes, however, that there are limits to Mead's concept of levels, as they tend to be organized as nested hierarchies. The emergence of a new reality (present) changes not only past and future, but pushes the present into a constant state of flux and change, which further alters the past and future.

It's a fun house mirror of theoretical madness.

-

Not the number of levels or their content are at issue here since these might be varied according to the degree of the analysis' generality but their static developmental stages where the level 'below' is denied aspects that characterise the level 'above'. In other words, whilst theories of time levels are theoretically of interest and echoed in many subsequent social science conceptualisations -including those of Sorokin ( 1964) and Elias (1982a, b, 1984), for example -they deny to non-human nature what we have found to be central: the importance of past, present, and future extension; of history, creativity, temporality, time experience, and time norms. If time differ-ences are conceptualised with reference to stable, integrative levels then this prevents any understanding in terms of resonance and feedback loops. With discrete, unidirectional levels, consciousness cannot be shown to resonate throughout all of nature; and what we think of as 'human time' stays falsely imprisoned at that level.

Adam contends that if time layers are viewed as bounded levels then "this prevents any understanding in terms of resonance and feedback loops."

She also talks about "discrete, unidirectional levels." This congers up thoughts about Bluedorn's writing about "time's directional arrow." Is this the same thing?

-

Despite these important advantages, however, there are difficulties associated with the conceptualisation of social time in terms of levels. These relate to our tendency to reify the levels, to conceptualise them hierarchically, and to postulate clear cut-off points between them. The three, as we shall see, are closely interconnected.

The idea of layers of time is problematic because people tend to want to transform abstract ideas into concrete examples (reify), assign rank order (hierarchy), and contain the layers (cut-off points).

-

A conceptualisation in terms of levels seems therefore well suited to explain and theorise the multitude of times entailed in contemporary life. To think of these times as expressions of different levels of our being avoids the need to discuss one aspect at the expense of all others. It means that we do not need to chose on an either/ or basis. It encourages us to see connections and not to lose sight of the multiplicity while we concentrate on any one of those multiple expressions.

Time is expressed in a variety of ways and conceptualizing them as levels allows people to imagine them holistically and as interconnected even while focusing on one aspect/layer.

However, this idea is contested further in the passage.

Does Adam's sense of time follow/counter Lindley's view of entangled time?

-

Recognising ourselves as having evolved, and thus being the times of nature, allows for the humanly constituted aspects of time to become one expression among the others. Biologists have dispelled the idea that only humans experience time or organise their lives by it. Waiting and timing in nature presuppose knowledge of time and temporality, irrespective of their being symbolised, conceptualised, reckoned, or measured. Yet, once time is constituted symbolically, it is no longer reducible to the communication of organisms or physical signals; it is no longer a mere sensory datum. For a person to have a past and to recognise and know it entails a representational, symbolically based imagination. Endowed with it, people do not merely undergo their presents and pasts but they shape and reshape them. Symbolic meaning thus makes the past infinitely flexible. With objectified meaning we can not only look back, reflect, and contemplate but we can reinterpret, restructure, alter, and modify the past irrespective of whether this is done in the light of new knowledge in the present, to suit the present, or for purposes of legitimation.

Still struggling a bit with this section but I think Adam is proposing that if we break down the barriers between understanding social time as symbolic and natural time as objective, that we can borrow methods of sensemaking from natural time and apply them to social time, it broadens our ways of knowing/understanding human temporal experience.

-

In other words, the idea of time as socially constituted depends fundamentally on the meaning we impose on 'the social', whether we understand it as a prerogative of human social organisation or, following Mead, as a principle of nature.

In a long prior passage about how time is conceptualized in nature and in social coordination, Adam argues that "time" as a social construct should be thought of holistically and not broken into dichotomies to be compared/contrasted.

-

A brief expansion of these general social science assumptions about nature will clarify this point. Nature as distinct from social life is understood to be quantifiable, simple, and subject to invariant relations and laws that hold beyond time and space (Giddens 1976; Lessnoff 1979· ~yan 1979). This view is accompanied by an understanding of natural time as coming in fixed, divisible units that can be measured whilst quality, complexit~, ~nd mediating knowledge are preserved exclusively for the conceptuahsat10n of human social time. On the basis of a further closely related idea it is proposed that nature may be understood objectively. Natural scientists, explain Elias (1982a, b) and Giddens ( 1976), stand in a subject-object relationship to their subject matter. Natural scientists, they suggest, are able to study objects directly and apply a causal framework of analysis whilst such direct causal links no longer suffice for the study of human society where that which is investigated has to be appreciated as unintended outcomes of intended actions and where the investigators interpret a pre-interpreted world. Unlike their colleagues in the natural sciences, social scientists, it is argued, stand in a subject-subject relation to their subject matter. In a?ditio? to the differences along the quantity-quality and object-subject d1mens10ns nature is thought to be predictable because its regularities -be they causal, statistical, or probabilistic -are timeless. The laws of nature. are c?nsi~ered to be true in an absolute and timeless way, the laws of society h1stoncally developed. In contrast to nature, human societies are argued to be fundamentally historical. They are organised around :alues, goals, morals, ethics, and hopes, whilst simultaneously being mfl~enc~d by tradition, habits, and legitimised meanings.

Critique of flawed social science perception of natural science as driven by laws, order, and quantitative attributes (subject-object) that are observable. This is contrasted with perception about social science as driven by history, culture, habit, and meanings which are socially constructed qualitative attributes (subject-subject).

-

Since our traditional understanding of natural time e~erged as inadequate and faulty we have to recognise that the analysis of social time is flawed by implication.

Adam states that "social time" theories should be contested since social science disciplinary understanding of "natural time" is incorrect.

-

Past, present, and future, historical time, the qualitative experience of time, the structuring of 'undifferentiated change' i?to episodes, all are established as integral time aspects of the subJect matter of the natural sciences and clock time, the invariant measure, the closed circle, the perfect symmetry, and reversible time as our creations.

Adam's broader definition of "natural time" which is socially constructed and not just a physical phenomena.

-

Sorokin and Merton (1937) may be said to have provided the 'definitive' classic statement on the distinction between social and natural time. They associate the physical time of diurnal and seasonal cycles with clock time and define this time as 'purely quantitative, shorn of qualitative variation' (p. 621). 'All time systems', Sorokin and Merton suggest further, 'may be reduced to the need of providing means for synchronising and co-ordinating the activities and observations of the constituents of groups' (p. 627).

classic definition of "social time" vs "natural time". This thinking is now contested.

-

Whilst social theorists are no longer united in the belief that all time systems are reducible to the functional need of human synchro~is_ation and co-ordination they seem to have little doubt about the validity of Sorokin and Merton's other key point that, unlike social time, the time of nature is that of the clock, a time characterised by invariance and quantity. Despite significant shifts in the understanding of social time, the assumptions about nature, natural time, and the subject matter of the natural sciences have remained largely unchanged.

Adam argues here that while the concept of "social time" has evolved, social scientists' ideas around "natural time" have not kept pace with new scientific research, and incorrectly continue to be described as constant and quantitative (aka clock time).

Further, "natural time" incorrectly incorporates other temporal experiences and seems to be used as a convenient counter foil to "social time"

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

Personal and organizational histories occupy prominent figure positions in the figure-ground dichotomy, and that such histories are used to cope with the future is indicated by several pieces of evidence.

Does this help to explain the need for SBTF volunteers to situate themselves in time -- as a way to construct a history in Weick's "figure-ground construction" method of sensemaking for themselves and to that convey sense to others?

-

Temporal focus is the degree of emphasis on the past, present, and future (Bluedorn 2000e, p. 124).

Temporal focus definition. Like temporal depth, both are socially constructed.

Cites Lewin (time perspective) and Zimbardo & Boyd.

-