1,926 Matching Annotations

- Aug 2019

-

material-components.github.io material-components.github.io

-

codesandbox.io codesandbox.io

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.smashingmagazine.com www.smashingmagazine.com

-

The US says ZIP code, whereas in Europe, it is postal code.

-

-

Placing Labels Above The Fields

-

-

www.smashingmagazine.com www.smashingmagazine.com

-

www.wisconsin.edu www.wisconsin.edu

-

TanyaJoosten

Tanya Joosten chaired UWisc's Learn@UW Roadmap Task Force.

-

-

www.cambridge.org www.cambridge.org

-

design thinking facilitates the intersection of understanding patients through human-centered design techniques to enhance patients’engagemen

Papel e importância do desing thinking na Saúde 4.0 = facilitar o entendimento na intersecção entre paciente e o HCD para promover engajamento

-

starts with understanding and influencing the experience of patients for the best possible outcome.

Papel inicial do design é entender a experiência do paciente.

-

Health 4.0; improved service and improved interconnectivity will be explored with respect to the three“pillars” of Health 4.0; people, technology and design

Melhorar a interconectividade em perder o foco nos três pilares da Saúde 4.0

-

emerging trend is design interaction

Prioriza a interconectividade - necessita do design de interação. Melhorar a relação entre pessoas, produtos, lugares e serviços.

-

three“pillars” of Health 4.0; people, technology and design.

Os 3 pilares da Saúde 4.0: pessoas, tecnologia e design

-

- Jul 2019

-

www.friscowebsoft.net www.friscowebsoft.net

-

Looking for expert web designer in Pleasanton, Dublin, CA or Livermore? We are a leading Walnut Creek-based website designing company. Call 1-877-249-1497 to know more!

-

-

www.friscowebsoft.com www.friscowebsoft.com

-

Looking for web design services in San Jose, CA? Frisco Web Solutions offers top rated web design services in San Jose. Call us at (408) 874-5254 to learn more about our expert web design services. We are professional website design company in San Jose offering responsive web design services through expert designers.

-

-

-

The times and lengths of the flights, and the count, times, and lengths of stops and transfers, can be compared visually.

neat, squeezing more information into two dimensions

-

This allows the viewer to differentiate between a book that was unanimously judged middling and one that was loved and hated —these are both

huh, that's a very neat idea

-

-

stonemaiergames.com stonemaiergames.com

-

12 Tenets of Board Game Design for Stonemaier Games

These tenets seem to fall from the Meta-Game (experience) idea discussed in board game design books.

-

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

-

A practical example of service design thinking can be found at the Myyrmanni shopping mall in Vantaa, Finland. The management attempted to improve the customer flow to the second floor as there were queues at the landscape lifts and the KONE steel car lifts were ignored. To improve customer flow to the second floor of the mall (2010) Kone Lifts implemented their 'People Flow' Service Design Thinking by turning the Elevators into a Hall of Fame for the 'Incredibles' comic strip characters. Making their Elevators more attractive to the public solved the people flow problem. This case of service design thinking by Kone Elevator Company is used in literature as an example of extending products into services.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.edge.org www.edge.orgEdge.org1

-

Unfortunately, misguided views about usability still cause significant damage in today's world. In the 2000 U.S. elections, poor ballot design led thousands of voters in Palm Beach, Florida to vote for the wrong candidate, thus turning the tide of the entire presidential election. At the time, some observers made the ignorant claim that voters who could not understand the Palm Beach butterfly ballot were not bright enough to vote. I wonder if people who made such claims have never made the frustrating "mistake" of trying to pull open a door that requires pushing. Usability experts see this kind of problem as an error in the design of the door, rather than a problem with the person trying to leave the room.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

- Jun 2019

-

www.researchgate.net www.researchgate.net

-

worrydream.com worrydream.com

-

Bob Barton [said] "The basic principle of recursive design is to make the parts have the same power as the whole." For the first time I thought of the whole as the entire computer, and wondered why anyone would want to divide it up into weaker things called data structures and procedures. Why not divide it up into little computers... Why not thousands of them, each simulating a useful structure?

-

-

ecbmurphy.pressbooks.com ecbmurphy.pressbooks.com

-

I love the way you're thinking about design and pedagogy here. It makes me want to think more about possibilities for such design...I'm wondering what the startup effort would be for many teachers...

-

-

antiflash.ru antiflash.ru

-

Фильтрация предполагает, что количество записей, после её применения, изменится. Формулировка кнопок фильтрации должна отвечать на вопрос «Что я получу после применения фильтрации?»: новое, мои записи, рестораны, непрочитанные письма и т. д. Применение сортировки не изменяет количество записей. Записи лишь меняют свой порядок. Формулировка должна отвечать на вопрос «По какому принципу упорядочены записи?»: по дате публикации, по рейтингу, в случайном порядке.

-

- May 2019

-

resources.chicagolx.org resources.chicagolx.org

-

codevelop learning goals with youth participants

-

-

thinkersco.com thinkersco.com

-

Persona ¿Qué es? Utilizamos la herramienta Persona para crear un modelo de usuario de nuestro objetivo. De esta manera tenemos una visión más profunda y personal a la hora de analizar las motivaciones y empatizar con nuestro usuario en la fase de ideación.

-

-

thinkersco.com thinkersco.com

-

In Out ¿Qué es? Estamos ante una herramienta que nos sirve para visualizar los límites de un proyecto. Con este mapa visual será más fácil comprender qué es o qué se encuentra dentro de nuestro proyecto y qué no.

-

-

thinkersco.com thinkersco.com

-

Análogos – Antílogos ¿Qué es? El objetivo de esta herramienta es ayudarnos a comprender y visualizar hacia qué punto queremos dirigir nuestra empresa o proyecto haciendo una comparación metafórica con otras empresas o entidades, ya sean del mismo campo o de otro completamente diferente. Para realizarlo, por un lado, hay que identificar y enumerar las entidades, empresas, individuos o proyectos a los que nos gustaría o creemos parecernos. Por otro lado, se debe buscar los análogos, es decir, empresas, individuos, entidades o proyectos a los que no nos gustaría o creemos parecernos.

-

-

thinkersco.com thinkersco.com

-

Cinco Porqués ¿Qué es? Esta herramienta la utilizamos para encontrar brevemente la base de un problema. Con los “cinco porqués” conseguimos llegar a la causa originaria del asunto que estamos tratando

-

-

thinkersco.com thinkersco.com

-

DAFO ¿Qué es? DAFO es una matriz de cuatro secciones que se utiliza para analizar la situación estratégica de una empresa. Por un lado estudia sus características internas (Debilidades y Fortalezas) y por el otro las características externas (Amenazas y Oportunidades).

-

-

opencontent.org opencontent.org

-

increases student success, reduces the cost of education, and supports rapid experimentation and innovation in education

It will be interesting to see if we can build layered materials that present important ideas or content at a variety of levels of detail/complexity for different subsets of students. For example, a module on the Columbian Exchange that has a “slider” to increase the depth of the coverage for different audiences.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

disquantified.org disquantified.org

-

The Disquantified Reading Group

This is not only a great reading list, but a model of how perhaps to structure a reading course with outward-facing content that makes its appeal wider than the single-semester cohort.

-

-

www.tandfonline.com www.tandfonline.com

-

tensions and tradeoffs of revision

Making annotation an important element of versioning things like textbooks.

-

collapsed the distance and distinction between producer and consumer

Another goal

-

performative publishing

Another useful term

-

laminated and multi-vocal text

Nice description -- design principle.

-

-

jackjamieson.net jackjamieson.net

-

I feel some apprehension about how this book might present designers’ “amazing amount of power.” I think designers work within a profound network of constraints, and I’m curious how this will be addressed.

I, too, share this apprehension. From what I've read so far, it's a tough hill to climb, but I think he'll suggest that designers need to have larger associations like doctors, architects, lawyers, etc. to be able to create a better "standard of care."

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

- Apr 2019

-

-

The Javits Center is often used by urbanists as an example of the perils of inhumane design. The unused and un-policed periphery attracts crime and vagrancy while its one entrance opens upon an eight lane street. This combination means that most conference attendees hire a taxi to ferry them to a more hospitable neighborhood.

This is an excellent example of creation without context, particularly use by target populations. Walkability was so poor that it negatively affected the area.

-

The only way to reach the Public Square promenade from the street is to climb three flights of stairs onto the High Line, then cross a fairly narrow bridge connection. The street level features a large cafeteria, but like the 10th avenue perimeter, the sidewalks are so narrow and the road so heavily trafficked with vehicles that it is unlikely the street can thrive as a public space.

Examples of why this space is not user-friendly and basically unwalkable. Those designing the space did not consider practicalities like access.

-

-

viennaprinciples.org viennaprinciples.org

-

A Vision for Scholarly Communication Currently, there is a strong push to address the apparent deficits of the scholarly communication system. Open Science has the potential to change the production and dissemination of scholarly knowledge for the better, but there is no commonly shared vision that describes the system that we want to create.

A Vision for Scholarly Communication

-

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

-

Wait list control group

-

- Mar 2019

-

www.idunn.no www.idunn.no

-

This paper discusses the idea that design is responsible for developing learning and teaching in technology rich environments. This paper argues Cultural Historical Activity Theory. This paper uses this perspective to discuss their ideas of design in connection with the digital age. This paper is written from the perspective German, Nordic, Russian and Vygotskyan concepts that seek to define the relationship between learning and teaching in relation to design. Rating 9/10 for mixing design with digital learning

-

-

teachonline.asu.edu teachonline.asu.edu

-

The Accessibility Guide

Arizona State University has a public webpage i nregards to accessibility and instructional design. The web page links to multiple online resources that outline accessibility standards across the United States. Additionally, this webpage provides an accessibility guide for anyone to download for instructional design related projects. Rating 9/10 for being a helpful resource that is easily accessible.

-

-

www.nhi.fhwa.dot.gov www.nhi.fhwa.dot.gov

-

This article reviews three learning styles and gives examples of how they fit into the three learning domains. Additionally this article reviews assumptions about adult learning and what it might actually mean. Lastly, this article reviews the instructional system design model and breaks down it's components. Rating 7/10 for lack of discussion but helpful tables

-

-

online-educator.pbworks.com online-educator.pbworks.com

-

The purpose of this paper is to propose an in-structional-design theory that supports a sense of community.

This article addresses the fact that new instructional design theories and methods are needed to keep up with new technologies and ways of learning. This article reviews instructional design tools for creating a sense of community online for learners. Additionally, this article discusses the differences between design theory and descriptive theory as it pertains to instructional design. 6/10 This article is very specific and might only be relevant for a specific study or topic

-

-

www.pacer.org www.pacer.org

-

Teaching Adults:What Every Trainer Needs to Know About Adult Learning Styles

This paper, a project o the PACER Center, discusses learning styles specifically as they pertain to adult learners. From the nitty-gritty podagogy vs. andragogy to the best ways to train for adults, this is a good tool for those who don't know much or need a refresher on adult learning theory and training adults. I love that it is set up in a textbook style, so it's friendly but has a considerable amount of information in a variety of formats. The section, "Tips for Teaching Adults" is helpful to me as it's a series of quick reminders about how to present my information best. 8/10

-

-

collegeforamerica.org collegeforamerica.org

-

How to Design Education for Adults

This wonderful how-to by Southern New Hampshire University provided several well explained tips about what adults need in their learning environments, including their own learning theory, goals, relevant instruction, treatment by the teacher, and participation. These are important things to keep in mind when training working adults because it may have an impact on what information is offered and how it is presented. I will use the information in this article later to help me present content in a meaningful way for my working adult learners. I want the content to be as relevant and inviting to them as possible. 9/10

-

-

academic.oup.com academic.oup.com

-

Training Older Adults To Use New Technology

This article, published in the Journals of Gerontology, discusses a study that focused on teaching older adults to use technology. This is often discussed in a practical sense, with many how-to's. This article, however, discusses the theory behind gerontological learning. Older adults don't generally learn the same way younger adults do. Therefore, it is important to provide them with practice that shows tasks have continuity, to ensure the important task components are focused on strongly, and to consider whether the learning goals are appropriate for the learner. Representative design is addressed here. This is the first time I've heard of representative design. I teach many people over the age of 60 to use technology, so it is important for me to know the theory that will help them learn best. Interestingly,this article mentioned that performance should be assessed based on a comparison of the older adult's environment. I wish I could use that more in my work, but it's a young person's world now. 9/10

-

-

www.shiftelearning.com www.shiftelearning.com

-

one main goal: they help you create effective learning experiences for the adult corporate learner.

This article takes on Adult Learning from an Instructional Design perspective. This article reviews 3 adult learning theories and why it's important for Instructional Designers to keep these theories in mind the facilitate the learning process. Rating: 9/10 for easy reading, overview of learning theories and emphasis on instructional design

-

-

online.rutgers.edu online.rutgers.edu

-

This webpage discusses different learning styles for adults, the principles of adult learning theory and different instructional design models for the the present and future. This webpage reviews andragogy and adult learning theory from the works of Malcolm Knowles. This article comes from Rutgers University and provides additional resources for adult learners. Ratings: 7/10 for helpful, short overview

-

-

onlineprograms.smumn.edu onlineprograms.smumn.edu

-

The benefits of personalized learning through technology This resource is included in part because it connects personalized learning and technology. A brief list of benefits, such as increasing student engagement and bridging the gap between teachers and students, are listed. This is presented by a marketing unit of a university so there may be an agenda. Nonetheless it provides useful considerations such as helping learners develop 'design thinking.' rating 3/5

-

-

www.dreambox.com www.dreambox.com

-

This site explains the features that instructional designers or others would integrate with personalized design. Based on a graphic, it may have been meant for K-12 students, but appears applicable to other forms of learning as well. This appears to be more credible and more informative than other pages I have found so far. rating 4/5

-

-

www.instructionaldesign.org www.instructionaldesign.org

-

Gagne's nine events of instruction I am including this page for myself because it is a nice reference back to Gagne's nine events and it gives both an example of each of the events as well as a list of four essential principles. It also includes some of his book titles. rating 4/5

-

-

www.interaction-design.org www.interaction-design.org

-

Shneiderman's eight golden rules of interface design This is a simple page that lists and briefly explains the eight golden rules of interface design. The rules are quite useful when designing interfaces and the explanation provided here is sufficient to enable the visitor to use the principles. Rating 5/5

-

-

www.valpo.edu www.valpo.edu

-

This link is to a three-page PDF that describes Gagne's nine events of instruction, largely in in the form of a graphic. Text is minimized and descriptive text is color coded so it is easy to find underneath the graphic at the top. The layout is simple and easy to follow. A general description of Gagne's work is not part of this page. While this particular presentation does not have personal appeal to me, it is included here due to the quality of the page and because the presentation is more user friendly than most. Rating 4/5

-

-

edutechwiki.unige.ch edutechwiki.unige.ch

-

Edutech wiki This page has a somewhat messy design and does not look very modern but it does offer overviews of many topics related to technologies. Just like wikipedia, it offers a good jumping off point on many topics. Navigation can occur by clicking through categories and drilling down to topics, which is easier for those who already know the topic they are looking for and how it is likely to be characterized. Rating 3/5

-

-

www.schrockguide.net www.schrockguide.net

-

This page is not necessarily attractive to look at but it is a thorough presentation of various features of infographics. Features are organized by topic and generally presented as a bulleted list. The focus of the page is how to use infographics for assessment; however, the page is useful to those who wish to learn how to create infographics and to identify the software tools that can be used to create them easily. Rating 4/5

-

-

www.asist.org www.asist.org

-

This link is for the Association of Information Science and Technology. While many of the resources are available only to those who are association members, there are a great many resources to be found via this site. Among the items available are their newsletter and their journal articles. As the title suggests, there is a technology focus, and also a focus on scientific findings that can guide instructional designers in the presentation and display of visual and textual information, often but not exclusively online. Instructional designers are specifically addressed via the content of this site. A student membership is available. Rating 5/5

-

-

faculty.washington.edu faculty.washington.edu

-

Shneiderman's eight golden rules Here is a better presentation than the one I already posted. This is just black and white text and lists the eight rules together with a description of one or two sentences. Printable. Useful. Rating 5/5

-

-

udlguidelines.cast.org udlguidelines.cast.org

-

UDL guidelines. As I post this, I do not know whether this website will be included in our future course readings or not. This website practices what it preaches and provides the same content in multiple forms. The viewer can select/choose the manner in which items are displayed. This has essential information, such as the need to provide "multiple means" of engagement, representation, action, and expression when teaching. Rating 5/5

-

-

elearningindustry.com elearningindustry.com

-

This page describes a method of teaching designed specifically for adults. The instructional design theory is Keller's "ARCS," which stands for attention, relevance, confidence, and satisfaction--all features that adult learning experiences should be characterized by. The text on this page is readable but the popups and graphics are a bit annoying. rating 3/5

-

-

wp0.vanderbilt.edu wp0.vanderbilt.edu

-

Teaching problem solving This page is included because some of our theories indicate that problem solving should be taught specifically. This page is a bit unusual; I did not find many others like it. It is rather easy to read and also addresses the differences between novice and expert learners. rating 3/5

-

-

inst-fs-iad-prod.inscloudgate.net inst-fs-iad-prod.inscloudgate.net

-

This is a description of the form of backward design referred to as Understanding by Design. In its simplest form, this is a three step process in which instructional designers first specify desired outcomes and acceptable evidence before specifying learning activities. This presentation may be a little boring to read as it is text-heavy and black and white, but those same attributes make it printer friendly. rating 3/5

-

-

www2.gsu.edu www2.gsu.edu

-

Mager's tips on instructional objectives This is a very simple page that consists of black and white text without any graphics. As is, the text on the page is rather small and difficult (for me, anyway) to read, so one may wish to enlarge it. The process of creating instructional objectives in this format is explained in a clear and straightforward way. Rating 5/5

-

-

techbuzztalk.com techbuzztalk.com

-

Seeking for some attractive and new app designs, in this blog we will share few latest mobile app design trends.

Seeking for some attractive and new app designs, in this blog we will share few latest mobile app design trends.

-

- Feb 2019

-

Local file Local file

-

Is the freedom of the individual served by neoliberalism? Centrality of the state for this freedom, which NL denies. “neoliberal thinkers deliberately sustain the fiction that ‘the market economy’ is a natural and spontaneous order that must be placed beyond politics … The question of how authority can be something other than domination and private power shaped the ideas and action of those who built the tradition of constitutional democracy in western societies from the 16th to the 20th centuries … basic needs were those that had to be met before the individual could practically enact the status of a free subject or person. It was such needs provision that made it possible for individuals to be both personally secure and to enjoy an equality of opportunity to develop as individuals free to discover their talents and gifts … the representation of market society as a spontaneous order is pitched to the punters while, within the tent of the doctrine’s initiates, it is fully understood that the state has to be both a strong state, and to be re-engineered in order to impose neoliberal institutional design.” YeatmanFreedom.pdf

-

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

-

for example, comments and identifiers

Some better illustrated examples can be found in UBCx: SoftConst2x - Software Construction: Object Oriented Design's course lecture on Coupling.

-

-

patternlab.io patternlab.io

-

- Jan 2019

-

muse.jhu.edu muse.jhu.edu

-

For example, an individual who believes that knowledge in a certain domain consists of a set of discrete, relatively static facts will likely achieve a sense of certainty on a research question much more quickly than someone who views knowledge as provisional, relative, and evolving.

But when curricula reinforce the confusion of speed and intelligence, that time may be precious.

-

additional motivation for test subjects to process information accurately made the impact of early preferences less prominent, though the influence did not disappear entirely

Interesting implications for assignment design.

-

-

blog.acolyer.org blog.acolyer.org

-

For large-scale software systems, Van Roy believes we need to embrace a self-sufficient style of system design in which systems become self-configuring, healing, adapting, etc.. The system has components as first class entities (specified by closures), that can be manipulated through higher-order programming. Components communicate through message-passing. Named state and transactions support system configuration and maintenance. On top of this, the system itself should be designed as a set of interlocking feedback loops.

This is aimed at System Design, from a distributed systems perspective.

-

-

courses.edx.org courses.edx.org

-

If one object is part of another object, then we use a diamond at the start of the arrow (next to the containing object), and a normal arrow at the end.

Another way of thinking of this is, if the original owner (source) object and the owned (target) object share the same life cycle -- that is, the owned exists only when the owner does -- we say that the owner aggregates owned object(s). They share a whole-part relationship.

What I did like very much about the video, was when the instructor pointed out that there's a small fallacy: aggregation, in OOD, does not really imply that owned object(s) must be a list.

-

-

getincredibles-fe.herokuapp.com getincredibles-fe.herokuapp.com

-

What's the stage your project is currently at?

This is a required field (add * at the end) Please remove the first option 'stage at which my project is currently at' from the dropdown as it's not an option one can choose.

Please also match the look and feel of this to the other drop downs..e.g. this one is grey, fonts seem different and it also animates/appears on the screen in a different way

-

-

www.maritime-executive.com www.maritime-executive.com

-

Contrary to mainstream thinking that this new technology is unregulated, it’s really quite the opposite. These systems apply the strictest of rules under highly deterministic and predictable models that are regulated through mathematics. In the future, industry will be regulated not just by institutions and committees but by algorithms and mathematics. The new technology will gradually out-regulate the regulators and, in many cases, make them obsolete because the new system offers more certainty. Antonopoulos explains that “the opposite of authoritarianism is not chaos, but autonomy.”

<big>评:</big><br/><br/>1933 年德国包豪斯设计学院被纳粹关闭,大部分师生移民到美国,他们同时也把自己的建筑风格带到了美利坚。尽管人们在严格的几何造型上感受到了冷漠感,但是包豪斯主义致力于美术和工业化社会之间的调和,力图探索艺术与技术的新统一,促使公众思考——「如何成为更完备的人」?而这一点间接影响到了我们现在所熟知的美国式人格。<br/><br/>区块链最终会超越「人治」、达到「算法自治」的状态吗?类似的讨论声在人工智能领域同样不绝于耳。「绝对理性」站到了完备人格的对立面,这种冰冷的特质标志着人类与机器交手后的败退。过去有怀疑论者担心,算法的背后实际上由人操控,但随着「由算法生成」的算法,甚至「爷孙代自承袭」算法的出现,这样的担忧逐渐变得苍白无力——我们有了更大的焦虑:是否会出现 “blockchain-based authoritarianism”?

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.comTitle13

-

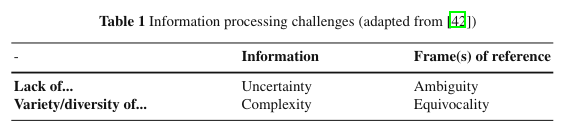

Zack [42] distinguished these four termsaccording to two dimensions: the nature of what is being processed and the consti-tution of the processing problem.The nature of what is being processed is either information or frames of ref-erence. With information, we mean “observations that have been cognitively pro-cessed and punctuated into coherent messages” [42]. Frames of reference [4, p.108], on the other hand, are the interpretative frames which provide the context forcreating and understanding information. There can be situations in which there is alack of information or a frame of reference, or too much information or too manyframes of reference to process.

Description of information processing challenges and breakdowns.

Uncertainty -- not enough information

Complexity -- too much information

Ambiguity -- lack of clear meaning

Equivocality -- multiple meanings

-

Ta b l e 3DERMIS design premises [29]

Muhren and Walle use the 6 of the 9 most relevant design premises for the future information system design guidelines for DERMIS, another crisis management system

Information focus (dealing with complexity)

Crisis memory (creating historical frames of reference)

Exceptions as norms (support changing frames of reference in fluid, unpredictable scenario)

Scope and nature of crisis (support adaptable management depending on type of crisis)

Information validity and timeliness (synergy of coping with uncertainty and creating frames of reference from relevant, known information)

Free exchange of information (synergy of social context and creating useful/sharable frames of reference)

-

For our research design, we drew on Walsham [33] and Klein and Myers [13],who provide comprehensive guidelines on how to conduct interpretive case studyresearch in the IS domain.

Bookmarked as a reminder to get these papers which could be helpful for the participatory design study.

-

The problems of managing information and managing frames of reference are“tightly linked in a mutually interacting loop” and require “managing informationand the systems that provide it” [42]. IS have been generally designed to overcomethe information problems from Table 1. Most IS are aimed at either storing and re-trieving information to reduce uncertainty, such as database management systemsand document repositories, or at analyzing and processing large amounts of infor-mation to reduce complexity, such as decision support systems [31]. However, aswe have previously discussed, information related strategies are not always helpfulin coping with a variety of potential meanings.Problems of interpretation and the creation and management of frames of refer-ence, which aids Sensemaking, have generally not been taken into account whendesigning IS. Most IS currently seem tointend the opposite because they aim atreplacing or suppressing the possibility tomake sense of situations.

Description of problem in integrating sensemaking (interpretive information process) into structured data systems.

information =/= data

-

there is scarce research on how IS can support informa-tion processing challenges—specifically related to Sensemaking—in crisis manage-ment [14]

Muhren and Walle also state that there are "few studies that use Sensemaking as an analytical lens for the design of information technology."

-

Sensemaking is about contextual rationality, built out of vaguequestions, muddy answers, and negotiated agreements that attempt to reduce ambi-guity and equivocality. The genesis of Sensemaking is a lack of fit between whatwe expect and what we encounter [40]. With Sensemaking, one does not look at thequestion of “which course of action should we choose?”, but instead at an earlierpoint in time where users are unsure whether there is even a decision to be made,with questions such as “what is going on here, and should I even be asking this ques-tion just now?” [40]. This shows that Sensemaking is used to overcome situationsof ambiguity. When there are too many interpretations of an event, people engagein Sensemaking too, to reduce equivocality.

Definition of sensemaking and how the process interacts with ambiguity and equivocality in framing information.

"Sensemaking is about coping with information processing challenges of ambiguity and equivocality by dealing with frames of reference."

-

Decision making is traditionally viewed as a sequential process of problem classifi-cation and definition, alternative generation, alternative evaluation, and selection ofthe best course of action [26]. This process is about strategic rationality, aimed atreducing uncertainty [6, 36]. Uncertainty can be reduced through objective analysisbecause it consists of clear questions for which answers exist [5, 40]. Complex-ity can also be reduced by objective analysis, as it requires restricting or reducingfactual information and associated linkages [42]

Definition of decision making and how this process interacts with uncertainty and complexity in information.

"Decision making is about coping with information processing challenges of uncertainty and complexity by dealing with information"

-

The central problem requiring Sensemaking ismostly that there are too many potential meanings, and so acquiring informationcan sometimes help but often is not needed. Instead, triangulating information [34],socializing and exchanging different points of view [20], and thinking back of pre-vious experiences to place the current situation into context, as the retrospectionproperty showed us, are a few strategies that are likely to be more successful forSensemaking.

Strategies for sensemaking

-

Just as the information processing challenges from Table 1 are not mutually ex-clusive, Sensemaking and decision making cannot be separated, but instead operatesimultaneously. Meaning must be established and then sufficiently negotiated priorto acting on information [42]: Sensemaking shapes events into decisions, and deci-sion making clarifies what is happening [40].

Interaction between sensemaking and decision making

-

Weick et al. [41, p. 419] formulate a gripping conclusion on what the sevenSensemaking properties are all about: “Taken together these properties suggest thatincreased skill at Sensemaking should occur when people are socialized to makedo, be resilient, treat constraints as self-imposed, strive for plausibility, keep show-ing up, use retrospect to get a sense of direction, and articulate descriptions thatenergize. These are micro-level actions. They are small actions. But they are smallactions with large consequences.”

Description of how the seven properties interact to foster sensemaking.

-

The seven different properties of Sensemaking can be captured by the acronym SIRCOPE: Social context, Identity construction, Retrospection, Cue extraction, Ongo-ing projects, Plausibility, and Enactment [17–21, 37–39]

"Weick distinguishes between seven properties of Sensemaking"

-

Crisis environments are characterized by various types of information problemsthat complicate the response, such as inaccurate, late, superficial, irrelevant, unreli-able, and conflicting information [30, 32]. This poses difficulties for actors to makesense of what is going on and to take appropriate action. Such issues of informationprocessing are a major challenge for the field of crisis management, both concep-tually and empirically [19].

Description of information problems in crisis environments.

-

We use the theory of Sensemaking to study exactly this: how people makesense of their environment, and how they give meaning to what is happening. Sense-making is a crucial process in crises, as the manner and thereby the success of howone deals with crucial events is determined by the grasp one has of a situation.

Sensemaking frame used in this study relies on work by Weick, et al.

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

Value Sensitive Design (VSD) emphasizes consideration of stakeholder values when making design decisions [5]. Applying this rationale to the goal of leveraging the capacity of digital workers during crisis events, we identify design solutions that fit the underlying community dynamics, including current work practices, organizational structures, and motivations of digital volunteer work.

Description of developing the design agenda, values, and needs assessment

Cites Value Sensitive Design

-

Our research reveals several design opportunities in this space. Importantly, informed by the empirical findings presented here, we argue for situating solutions within current work practices and infrastructures.

Description of design opportunities

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

Based on our collective research on to date, we haveidentified that as tensions ebb and flow, OCs use (or,more precisely, participants engage in) any of the fourtypes of responses that seem to help the OC be gen-erative. The first generative response is labeledEngen-dering Roles in the Moment. In this response, membersenact specific roles that help turn the potentially negativeconsequences of a tension into positive consequences.The second generative response is labeledChannelingParticipation. In this response, members create a nar-rative that helps keep fluid participants informed ofthe state of the knowledge, with this narrative havinga necessary duality between a front narrative for gen-eral public consumption and a back narrative to airthe differences and emotions created by the tensions.The third generative response is labeledDynamicallyChanging Boundaries. In this response, OCs changetheir boundaries in ways that discourage or encouragecertain resources into and out of the communities at cer-tain times, depending on the nature of the tension. Thefourth generative response is labeledEvolving Technol-ogy Affordances. In this response, OCs iteratively evolvetheir technologies in use in ways that are embedded by,and become embedded into, iteratively enhanced socialnorms. These iterations help the OC to socially and tech-nically automate responses to tensions so that the com-munity does not unravel.

Productive responses to experienced tensions.

Evokes boundary objects (dynamically changing boundaries) and design affordances/heuristics (evolving technology affordances)

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

These practices are highly situated, emer-gent, and contextualized and thus cannot be prespec-ified the way traditional coordination mechanismscan be. Thus, recent efforts based on an information-processing view to develop typologies of coordina-tion mechanisms (e.g., Malone et al. 1999) may be tooformal to allow organizations to mount an effectiveresponse to events characterized by urgency, novelty,surprise, and different interpretations.

More design challenges

-

Our findings also point to a broader divide in coor-dination research. Much of the power of traditionalcoordination models resides in their information-processing basis and their focus on the design issuessurrounding work unit differentiation and integra-tion. This design-centric view with its emphasis onrules,structures,andmodalitiesofcoordinationislessuseful for studying knowledge work.

The high-tempo, non-routine, highly situated knowledge work of SBTF definitely falls into this category. Design systems/workarounds is challenging.

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

By ignoring the diversity and discord of the ‘goals’ of theparticipants involved, the differentiation of strategies, and the incongruence of theconceptual frames of reference within a cooperating ensemble, much of the currentCSCW research evades the problem of how to provide computer support for peoplecooperating through the establishment of a common information space.

Has this design challege been adequately addressed in CSCW (and CHI, for that matter) in the last 30-ish years?

-

On the one hand, the visibility requirement is amplified by this divergence. Thatis, knowledge of the identity of the originator and the situational context motivat-ing the production and dissemination of the information is required so as to enableany user of the information to interpret the likely motives of the originator. On theother hand, however, the visibility requirement is moderated by the divergence ofinterests and motives. A certain degree of opaqueness is required for discretionarydecision making to be conducted in an environment charged with colliding inter-ests. Hence,visibility must be bounded.

What role does system meta data (version control, user history, etc.) play in bounding the visibility of decision making?

This also seems to be an area ripe for more collaborative design approaches (participatory, reflective, feminist, etc.)

-

Thus, a computer-basedsystem supporting cooperative work involving decision making should enhancethe ability of cooperating workers to interrelate their partial and parochial domainknowledge and facilitate the expression and communication of alternative perspec-tives on a given problem. This requires a representation of the problem domainas a whole as well as a representation, in some form, of the mappings betweenperspectives on that problem domain.

This seems to still be a major challenge in information system design as well as collaborative workflow. Even if the information/meta context is made available, do people use it?

-

-

dl.acm.org dl.acm.org

-

Reflective Design Strategies In addition shaping our principles or objectives, our foundational influences and case studies have also helped us articulate strategies for reflective design. The first three strategies identified here speak to characteristics of designs that encourage reflection by users. The second group of strategies provides ways for reflecting on the process of design.

verbatim from subheads in this section

1.Provide for interpretive flexibility.

2.Give users license to participate.

3.Provide dynamic feedback to users.

4.Inspire rich feedback from users.

5.Build technology as a probe.

6.Invert metaphors and cross boundaries.

-

Some Reflective Design Challenges

The reflective design strategies offer potential design interventions but lack advice on how to evaluate them against each other.

"Designing for appropriation requires recognizing that users already interact with technology not just on a superficial, task-centered level, but with an awareness of the larger social and cultural embeddedness of the activity."

-

Principles of Reflective Design

verbatim from subheads in this section

Designers should use reflection to uncover and alter the limitations of design practice

Designers should use reflection to re-understand their own role in the technology design process.

Designers should support users in reflecting on their lives.

Technology should support skepticism about and reinterpretation of its own working.

Reflection is not a separate activity from action but is folded into it as an integral part of experience

Dialogic engagement between designers and users through technology can enhance reflection.

-

Reflective design, like reflection-in-action, advocates practicing research and design concomitantly, and not only as separate disciplines. We also subscribe to a view of reflection as a fully engaged interaction and not a detached assessment. Finally, we draw from the observation that reflection is often triggered by an element of surprise, where someone moves from knowing-in-action, operating within the status quo, to reflection-in-action, puzzling out what to do next or why the status quo has been disrupted

Influences from reflection-in-action for reflective design values/methods.

-

In this effort, reflection-in-action provides a ground for uniting theory and practice; whereas theory presents a view of the world in general principles and abstract problem spaces, practice involves both building within these generalities and breaking them down.

A more improvisational, intuitive and visceral process of rethinking/challenging the initial design frame.

Popular with HCI and CSCW designers

-

CTP is a key method for reflective design, since it offers strategies to bring unconscious values to the fore by creating technical alternatives. In our work, we extend CTP in several ways that make it particularly appropriate for HCI and critical computing.

Ways in which Senger, et al., describe how to extend CTP for HCI needs:

• incorporate both designer/user reflection on technology use and its design

• integrate reflection into design even when there is no specific "technical impasse" or metaphor breakdown

• driven by critical concerns, not simply technical problems

-

CTP synthesizes critical reflection with technology production as a way of highlighting and altering unconsciously-held assumptions that are hindering progress in a technical field.

Definition of critical technical practice.

This approach is grounded in AI rather than HCI

(verbatim from the paper) "CTP consists of the following moves:

• identifying the core metaphors of the field

• noticing what, when working with those metaphors, remains marginalized

• inverting the dominant metaphors to bring that margin to the center

• embodying the alternative as a new technology

-

Ludic design promotes engagement in the exploration and production of meaning, providing for curiosity, exploration and reflection as key values. In other words, ludic design focuses on reflection and engagement through the experience of using the designed object.

Definition of ludic design.

Offers a more playful approach than critical design.

-

goal is to push design research beyond an agenda of reinforcing values of consumer culture and to instead embody cultural critique in designed artifacts. A critical designer designs objects not to do what users want and value, but to introduce both designers and users to new ways of looking at the world and the role that designed objects can play for them in it.

Definition of critical design.

This approach tends to be more art-based and intentionally provocative than a practical design method to inculcate a certain sensibility into the technology design process.

-

value-sensitive design method (VSD). VSD provides techniques to elucidate and answer values questions during the course of a system's design.

Definition of value-sensitive design.

(verbatim from the paper)

*"VSD employs three methods :

• conceptual investigations drawing on moral philosophy, which identify stakeholders, fundamental values, and trade-offs among values pertinent to the design

• empirical investigations using social-science methods to uncover how stakeholders think about and act with respect to the values involved in the system

• technical investigations which explore the links between specific technical decisions and the values and practices they aid and hinder" *

-

From participatory design, we draw several core principles, most notably the reflexive recognition of the politics of design practice and a desire to speak to the needs of multiple constituencies in the design process.

Description of participatory design which has a more political angle than user-centered design, with which it is often equated in HCI

-

PD strategies tend to be used to support existing practices identified collaboratively by users and designers as a design-worthy project. While values clashes between designers and different users can be elucidated in this collaboration, the values which users and designers share do not necessarily go examined. For reflective design to function as a design practice that opens new cultural possibilities, however, we need to question values which we may unconsciously hold in common. In addition, designers may need to introduce values issues which initially do not interest users or make them uncomfortabl

Differences between participatory design practices and reflective design

-

We define 'reflection' as referring tocritical reflection, orbringing unconscious aspects of experience to conscious awareness, thereby making them available for conscious choice. This critical reflection is crucial to both individual freedom and our quality of life in society as a whole, since without it, we unthinkingly adopt attitudes, practices, values, and identities we might not consciously espouse. Additionally, reflection is not a purely cognitive activity, but is folded into all our ways of seeing and experiencing the world.

Definition of critical reflection

-

Our perspective on reflection is grounded in critical theory, a Western tradition of critical reflection embodied in various intellectual strands including Marxism, feminism, racial and ethnic studies, media studies and psychoanalysis.

Definition of critical theory

-

ritical theory argues that our everyday values, practices, perspectives, and sense of agency and self are strongly shaped by forces and agendas of which we are normally unaware, such as the politics of race, gender, and economics. Critical reflection provides a means to gain some awareness of such forces as a first step toward possible change.

Critical theory in practice

-

We believe that, for those concerned about the social implications of the technologies we build, reflection itself should be a core technology design outcome for HCI. That is to say, technology design practices should support both designers and users in ongoing critical reflection about technology and its relationship to human life.

Critical reflection can/should support designers and users.

-

- Dec 2018

-

www.animationnights.com www.animationnights.com

-

A: Anything else you’d like to say or tell the new comers and/or the community? L: Mmh, I know how it feels to be limited by your own lack of skills and today’s tools are taking away a little bit of that barrier. And the more the software helps you to get rid of the technical problems of representation, the more creative you can be. While the tool is the same, it’s very fun to see that everybody has its own take to how to use Quill. It wasn’t at first, but now I see more and more people having their own style. It’s so refreshing. I follow the group and what is going on with a lot of attention.

-

L: It happened to us a couple of times to come up with these kinds of ideas where the audience really understands what we meant and feels as strongly as we did. We want to communicate feelings that we feel ourselves. Whatever the tool is, we wish to convey what we think is great. It sounds a little bit cliché but if you’re out just for the pretty picture, I think it’s a waste of time.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

thedesignkids.org thedesignkids.org

-

Where did you study and what were some of your first jobs? I actually have a degree in Economics from Colorado College. This was pursued at the behest of my father and after bartending for a year in London after I graduated, I went to the Vancouver Film School and took their course in Multimedia. My first jobs were all menial labor: I worked sorting packages at a Greyhound station, cleaning recycled bottles at a brewery and erected party tents. After VFS, I moved to New York and freelanced as a web designer/flash animator for a bit before I helped found heavy.com with two of the guys I had been freelancing for. That lasted for about five years before I started Buck with my partners in 2003.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

participatory approach is compatible with empathic user research [81] that avoids the scientific distance that cuts the bonds of humanity between researcher and subject, pre-empting a major resource for design (empathy, love, care).

Definition of participatory design

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

Theproblem, then, was centered by social scientists in the process of design. Cer-tainly, many studies in CSCW, HCI, information technology, and informa-tion science at least indirectly have emphasized a dichotomy betweendesigners, programmers, and implementers on one hand and the social ana-lyst on the other.

Two different camps on how to resolve this problem:

1) Change more flexible social activity/protocols to better align with technical limitations 2) Make systems more adaptable to ambiguity

-

In particular, concurrency control problems arise when the software, data,and interface are distributed over several computers. Time delays when ex-changing potentially conflicting actions are especially worrisome. ... Ifconcurrency control is not established, people may invoke conflicting ac-tions. As a result, the group may become confused because displays are incon-sistent, and the groupware document corrupted due to events being handledout of order. (p. 207)

This passage helps to explain the emphasis in CSCW papers on time/duration as a system design concern for workflow coordination (milliseconds between MTurk hits) versus time/representation considerations for system design

-

-

scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org

-

Edward Tufte

I wish all academics would read Tufte before ever creating a slide deck :)

-

-

dornsife.usc.edu dornsife.usc.edu

-

Noguidance was given to the participants regarding what topography or function of behavior to choose, nor which client tochoose. The BIPs that were submitted included a wide range of behavior topographies and functions, as depicted inTables 2 and 3. The ages of the clients ranged significantly, but were roughly equivalent across the two groups, witha mean age of 8.75 years (range = 3–19) in the treatment group and a mean age of 7.75 years (range = 4–10) in thecontrol group. It seems reasonable that due to reactivity, participants would choose to send a BIP that they believedwas good-quality, however, this reactivity was likely to be equally distributed across groups. Each BIP was then scoredas the pre-test data for that participant. For participants in the control group, the participant was then asked to updatetheir BIP however they see fit over the next 24 h and resubmit it. For participants in the BIP builder group, they wereasked to update their BIP using the BIP builder within the next 24 h. No further instructions were given to theparticipants.

-

-

www.centerartsdesign.org www.centerartsdesign.org

-

Dalida

-

- Nov 2018

-

logicmag.io logicmag.io

-

how does misrepresentative information make it to the top of the search result pile—and what is missing in the current culture of software design and programming that got us here?

Two core questions in one? As to "how" bad info bubbles to the top of our search results, we know that the algorithms are proprietary—but the humans who design them bring their biases. As to "what is missing," Safiya Noble suggests here and elsewhere that the engineers in Silicon Valley could use a good dose of the humanities and social sciences in their decision-making. Is she right?

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

I don't think passing the entire http client is very idiomatic, but what is quite common is to pass the entire "environment" (aka runtime configuration) that your app needs through every function. In your case if the only variant is the URL then you could just pass the URL as the first parameter to get-data. This might seem cumbersome to someone used to OO programming but in functional programming it's quite standard. You might notice when looking at example code, tutorials, open source libraries etc. that almost all code that reads or writes to databases expects the DB connection information (or an entire db object) as a parameter to every single function. Another thing you often see is an entire "env" map being passed around which has all config in it such as endpoint URLs.

passing state down the call stack configuration, connection, db--pretty common in FP

-

Something that I've found helps greatly with testing is that when you have code with lots of nested function calls you should try to refactor it into a flat, top level pipeline rather than a calling each function from inside its parent function. Luckily in clojure this is really easy to do with macros like -> and friends, and once you start embracing this approach you can enter a whole new world of transducers. What I mean by a top level pipeline is that for example instead of writing code like this: (defn remap-keys [data] ...some logic...) (defn process-data [data] (remap-keys (flatten data))) (defn get-data [] (let [data (http/get *url*)] (process-data data))) you should make each step its own pure function which receives and returns data, and join them all together at the top with a threading macro: (defn fetch-data [url] (http/get url)) (defn process-data [data] (flatten data)) (defn remap-keys [data] ...some logic...) (defn get-data [] (-> *url* fetch-data process-data remap-keys)) You code hasn't really changed, but now each function can be tested completely independently of the others, because each one is a pure data transform with no internal calls to any of your other functions. You can use the repl to run each step one at a time and in doing so also capture some mock data to use for your tests! Additionally you could make an e2e tests pipeline which runs the same code as get-data but just starts with a different URL, however I would not advise doing this in most cases, and prefer to pass it as a parameter (or at least dynamic var) when feasible.

testing flat no deep call stacks, use pipelines

-

One thing Component taught me was to think of the entire system like an Object. Specifically, there is state that needs to be managed. So I suggest you think about -main as initializing your system state. Your system needs an http client, so initialize it before you do anything else

software design state on the outside, before anything else lessions from Component

-

-

joannalynwilliams.com joannalynwilliams.com

-

ADVERTISEMENT

If you're going to include ads in your app, they need to be actual images. This looks broken.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.irrodl.org www.irrodl.org

-

Learning needs analysis of collaborative e-classes in semi-formal settings: The REVIT exampl

This article explores the importance of analysis of instructional design which seems to be often downplayed particularly in distance learning. ADDIE, REVIT have been considered when evaluating whether the training was meaningful or not and from that a central report was extracted and may prove useful in the development of similar e-learning situations for adult learning.

RATING: 4/5 (rating based upon a score system 1 to 5, 1= lowest 5=highest in terms of content, veracity, easiness of use etc.)

-

-

www.shiftelearning.com www.shiftelearning.com

-

In addition to discussing Knowles Andragogy learning theory this article also looks into two other adult learning theories: experiential and transformational. For learning to be successful in adults instructional designers need to "tap into prior experiences," "create a-ha moments," and "create meaning" by connecting to reality. Rating: 5/5

-

-

www.joe.org www.joe.org

-

Thinking in Multimedia: Research-Based Tips on Designing and Using Interactive Multimedia Curricula.

This article examines various methods of delivery: multimedia integration, possibly including audio, video, slides, and animation. The recommendation is to carefully consider which online delivery mode matches with the learner, and to be cognizant that not everyone learns in the same manner. Certain topics may be best presented in live videos and not in power-point slides show as meaning may be lost or not delivered correctly. It’s important to follow-up with immediate assessment and feedback to continue to develop effective training.

RATING: 5/5 (rating based upon a score system 1 to 5, 1= lowest 5=highest in terms of content, veracity, easiness of use etc.)

-

-

eric.ed.gov eric.ed.gov

-

Instructional Design Strategies for Intensive Online Courses: An Objectivist-Constructivist Blended Approach

This was an excellent article Chen (2007) in defining and laying out how a blended learning approach of objectivist and constructivist instructional strategies work well in online instruction and the use of an actual online course as a study example.

RATING: 4/5 (rating based upon a score system 1 to 5, 1= lowest 5=highest in terms of content, veracity, easiness of use etc.)

Tags

- instructional methods

- instructional design systems

- etc556

- instructional technology

- instructiveness effectiveness

- constructivism

- distance education

- Instructional systems design; Distance education; Online courses; Adult education; Learning ability; Social integration

- etcnau

- Performance Factors, Influences, Technology Integration, Teaching Methods, Instructional Innovation, Case Studies, Barriers, Grounded Theory, Interviews, Teacher Attitudes, Teacher Characteristics, Technological Literacy, Pedagogical Content Knowledge, Usability, Institutional Characteristics, Higher Education, Foreign Countries, Qualitative Research

- online education growth

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.ncolr.org www.ncolr.org

-

The Importance of Interaction in Web-Based Education: A Program-level Case Study of Online MBA Courses

This case study explores perceptions of instructors vs. end-users with web-based training. It examines various technologies and techniques.

RATING: 4/5 (rating based upon a score system 1 to 5, 1= lowest 5=highest in terms of content, veracity, easiness of use etc.)

-

-

buildfire.com buildfire.com

-

How To Create A Mobile App in 10 Easy Steps

Buildfire is a site that presents how to create a mobile app in 10 easy steps. Site is easy to read and use.

RATING: 4/5 (rating based upon a score system 1 to 5, 1= lowest 5=highest in terms of content, veracity, easiness of use etc.)

-

-

-

Prezi is a productivity platform that allows for creation, organization, collaboration of presentations. It can be used with either mobile or desktop. Prezi integrates with slack and salesforce. RATING: 5/5 (rating based upon a score system 1 to 5, 1= lowest 5=highest in terms of content, veracity, easiness of use etc.)

-

-

search.proquest.com search.proquest.com

-

Older adult learning environment preferences

Older adult preferences.is a dissertation preview that introduces the dissertation on preference of older adults to attend in person classes weekly for four to six hours.

The information gleaned from this study is significant for learning designers and course structure. The study also investigated the time and location of the study, and the class make up. This information also warrants further investigation when designing courses for these adults and the success of the program. The dissertation is of value to those who are specifically involved in designing programs for older adults.

RATING: 8/10

-

-

er.educause.edu er.educause.edu

-

format in which these materials are available to students, then, has an impact on students' willingness to access and use materials,

This is very much a design concept. Where do "we" like to access and engage with material?

-

-

www.microsoft.com www.microsoft.com

-

Holographic computing made possible

Microsoft hololens is designed to enable a new dimension of future productivity with the introduction of this self-contained holographic tools. The tool allows for engagement in holograms in the world around you.

Learning environments will gain ground with the implementation of this future tool in the learning program and models.

RATING: 5/5 (rating based upon a score system 1 to 5, 1= lowest 5=highest in terms of content, veracity, easiness of use etc.)

-

-

educationaltechnology.net educationaltechnology.net

-

“The ADDIE model consists of five steps: analysis, design, development, implementation, and evaluation. It is a strategic plan for course design and may serve as a blueprint to design IL assignments and various other instructional activities.”

This article provides a well diagrammed and full explanation of the addie model and its' application to technology.

Also included on the site is a link to an online course delivered via diversityedu.com

RATING: 4/5 (rating based upon a score system 1 to 5, 1= lowest 5=highest in terms of content, veracity, easiness of use etc.)

-

-

create-center.ahs.illinois.edu create-center.ahs.illinois.eduCREATE1

-

CREATE Overview

Create is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing resources for the development and creation of educational technology to enhance the independence and productivity of older adult learners.

The sight includes publications, resources, research, news, social media and information all relevant to aging and technology. It is the consortium of five universities including: Weill Cornell Medicine,University of Miami, Florida State University,Georgia Institute of Technology, and University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

RATING: 4/5 (rating based upon a score system 1 to 5, 1= lowest 5=highest in terms of content, veracity, easiness of use etc.)

-

-

files.eric.ed.gov files.eric.ed.gov

-

Six Steps to Personalize Learning

This pdf is a step by step guide to develop personalized learning. It includes instructions to creating a six-step personalized learning program.

I enjoyed the at-a-glance chart distinguishing the differences between personalization, differentiation and individualization. The guide is very visual and easy to ready but offers relevant tips.

RATING: 4/5 (rating based upon a score system 1 to 5, 1= lowest 5=highest in terms of content, veracity, easiness of use etc.)

-

-

eds.b.ebscohost.com.libproxy.nau.edu eds.b.ebscohost.com.libproxy.nau.edu

-

Towards teaching as design: Exploring the interplay between full-lifecycle learning design tooling and Teacher Professional Development.

This article explores the theory of training teachers as learning designers to promote innovate and creativity. Included in the article are studies of designers with little teaching experience compared with those that are full-cycle teachers and the effect of TPD and LD upon training.

RATING: 5/5 (rating based upon a score system 1 to 5, 1= lowest 5=highest in terms of content, veracity, easiness of use etc.)

-

-

-

The Moodle project

Moodle is one of the largest open source collaborative platform used in the development of curriculum.

Moodle is an Australian company and has various levels of subscriptions including one level for free. Overall I have found the site to be user friendly rich with demos, documentation and support including community forums. This site supports multiple languages and has an easy to use drop down menu for that selection.

RATING: 5/5 (rating based upon a score system 1 to 5, 1= lowest 5=highest in terms of content, veracity, easiness of use etc.)

-

-

ctet.royalroads.ca ctet.royalroads.ca

-

Learning Design Process

The Royal Roads University has created this useful site that offers support and assistance in the design and development of curriculum. What I found to be very useful is the support dedicated for Moodle, the online curriculum software as I have recently signed up for the site.

The methodology used by the University is focused on an outcomes approach with integration of pedagogical and technological elements and blended learning.

The site has a research link and the kb was excellent. I was very pleased to have found this resource.

RATING: 5/5 (rating based upon a score system 1 to 5, 1= lowest 5=highest in terms of content, veracity, easiness of use etc.)

-

-

eds.a.ebscohost.com.libproxy.nau.edu eds.a.ebscohost.com.libproxy.nau.edu

-

Learning Needs Analysis of Collaborative E-Classes in Semi-Formal Settings: The REVIT Example.

This article explores the importance of analysis of instructional design which seems to be often downplayed particularly in distance learning. ADDIE, REVIT have been considered when evaluating whether the training was meaningful or not and from that a central report was extracted and may prove useful in the development of similar e-learning situations for adult learning.

RATING: 4/5 (rating based upon a score system 1 to 5, 1= lowest 5=highest in terms of content, veracity, easiness of use etc.)

-

- Oct 2018

-

fqa.9front.org fqa.9front.org

-

Rob Pike has described Plan 9 as "an argument" for simplicity and clarity, while others have described it as "UNIX, only moreso."

idea of a system as an argument pointed out by: https://twitter.com/rsnous/status/1054631468142493696

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

Slow Design (Strauss & Fuad-Luke, 2009) celebrates slowness as an answer to critical issues in design, such as an often-perceived support to consumerism, a restrictive focus on functionalism, the diminishment of users’ engagement with materials, a lack of attention to local idiosyncrasies, and the need to think in the long-term.

A definition of "slow design" to think sideways for long-term sustainance.

-

-

www.seanmichaelmorris.com www.seanmichaelmorris.com

-

Critical Instructional Design is new, and as such is grounded in the work of a very few people.

I'm interested if the conception 'Critical Instructional Design' is truly new or mere interpolation of a native concept. As far as my understanding of critical theory, from lit crit readings and study, a theory can be molded to fit any necessary unnamed reality-from the nature of the TV War... Baudrillard's 'The Gulf War Did Not Take Place' to Freudian psychoanalysis "Neuroticisms of Computer A.I." This is an excellent article to discuss critical theory in the light of a new, online iteration of the learning space meriting further research.

-

-

www.powazek.com www.powazek.com

-

Designing for selfishness does not mean abandoning the group good.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

cnx.org cnx.org

-

Federalism has the capability of being both bad and good. It just depends who you ask. On one side the advantages of fedaralism is it creates more effectiveness and makes the government stable. On the other hand federalism is risky it gets expensive, lead to a complex tax system and is slow in responses to crisis.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

- Sep 2018

-

-

Now an impoverished Marxist cultural critique suggests that such encounters between people, qua humans with richly diverse lives, are the very opposite of — or further, directly opposed by — the alienated encounters underwritten, if not compelled, by money. You see this kind of argument when people say “the ‘sharing economy’ is an oxymoron that has nothing to do with sharing because people are lending their underutilized resources for financial recompense.” However, what has always seemed to me most interesting about many ‘sharing economy’ platforms is not that they are spaces outside of commercialism, but rather ways of affording a re-embedding of economic exchanges in social relations within commercialism. When I ride-share or home-share, there might be money changing hands, but the actual experience of the ‘service’ is of two people (when there are face-to-face encounters) who cannot entirely withdraw into prescribed roles of employee and customer. This is why these ‘sharing economy’ experiences tend to be awkward, in ways that I have tried to argue are in fact deconstructive of the monolithically abstract idea of capitalism.These moments underline that there can be ‘sharing’ within economies, that relations between strangers do occur at levels or in ways beyond what is covered by their monetization. Service designing, it seems to me, is precisely the pursuit of these forms of sociality that exceed commercialism even within commercial interactions. This is the quality that a well-designed service encounter will manifest, a quality that will differentiate such a service from other less-designed ways of managing or engineering services.Service designers should therefore be expertly sensitive to these emergent and sometimes even resistant socialities. Designers should understand that at the very core of their practice is all that is concealed by excessively capitalistic perspectives: the hidden labor of informal economies; the emotional and aesthetic labor provision that service interactions compel from providers without adequate recompense; the satisfiers that make care work rewarding beyond their inequitable pay scales; the moments of delight involved in the comfort of strangers. All of these, it should be clear, are political, sensitivities that acknowledge oppression and exploitation via gender, race and class.All this is why service design is never just the design of this or that service, but part of the wider project of redesigning work and generating sustainable livelihoods. For instance, service design is not tangential to current debates about the roboticization of jobs. Service design is unavoidably involved in Transition Design, toward or away from meaningful work, or rather perhaps toward or away from quality ways of organizing the resourcing of new kinds of society.

-

Product designers tend to aim to create tools that should be appreciated in their own right for what they help accomplish — what the philosopher of technology, Albert Borgmann calls a focal thing. These well-designed products are valued for what they enable someone skilled to do with them. The service designer is less concerned with developing a refined product, valued for its versatility or finesse, and more concerned with a material means to an end, an enabler of a service interaction. This means that those products need to be more ‘alive’ to the needs of the participants in the service. They need to be less present in their own materiality, and more automated or responsive, directing the interactions between the service co-creators.This means that service designers must have a particularly acute sense of the agency of things. All designers understand the weak forces — affordances — that the forms of things exert on users in the appropriate contexts. For service designers, these forces must be more dynamically deployed because the point is less the products themselves and more the experiences they enable but even at times direct. Compared to a product that will be used regularly, and perhaps diversely, by an owner, the touchpoints that service designers design need to be more subservient to the overall experience. They should be more sensitive to a diversity of users and use cases on the one hand, but more focused on accomplishing just this or that transition in the service journey. This means that they tend to be more animated by intention than the artifacts conventionally produced by product designers. But paradoxically, this makes them less materially present as things. A product within a service pro-duces, leads forth, by being more of a sub-ject, something underlying the process, rather than an ob-ject, something jutting out with physical presence.

-