Kaube, Jürgen. “Zettelkästen: Alles und noch viel mehr: Die gelehrte Registratur.” FAZ.NET, June 3, 2013. https://www.faz.net/aktuell/feuilleton/geisteswissenschaften/zettelkaesten-alles-und-noch-viel-mehr-die-gelehrte-registratur-12103104.html

- Oct 2022

-

-

-

Doch ganz gleich, ob der Zettelkasten auf ein Buch, ein Werk oder auf eine Gedankenwolke mit wechselnder Niederschlagsneigung hinauslief - er ist stets mehr als das Ganze, dessen Teile er gesammelt hat. Denn es stecken stets noch andere Texte in ihm als diejenigen, die aus ihm hervorgegangen sind. Insofern wäre die Digitalisierung des einen oder anderen Zettelkastens ein Geschenk an die Wissenschaft.

machine translation (Google):

But regardless of whether the Zettelkasten resulted in a book, a work, or a thought cloud with varying degrees of precipitation - it is always more than the whole whose parts it has collected. Because there are always other texts in it than those that emerged from it.

There's something romantic about the analogy of a zettelkasten with a thought cloud which may have varying degrees of precipitation.

Link to other analogies: - ruminant machines - the disappointment of porn - others?

-

Andere Sammlungen sind ihrem Verwendungszweck nie zugeführt worden. Der Germanist Friedrich Kittler etwa legte Karteikarten zu allen Farben an, die dem Mond in der Lyrik zugeschrieben worden sind. Das Buch dazu könnte jemand mit Hilfe dieser Zettel schreiben.

machine translation (Google):

Other collections have never been used for their intended purpose. The Germanist Friedrich Kittler, for example, created index cards for all the colors that were ascribed to the moon in poetry. Someone could write the book about it with the help of these slips of paper.

Germanist Friedrich Kittler collected index cards with all the colors that were ascribed to the moon in poetry. He never did anything with his collection, but it has been suggested that one could write a book with his research collection.

-

Nicht wenige Kästen sind nur für ein einziges Buch angelegt worden, Siegfried Kracauers Sammlungen etwa zu seiner Monographie über Jacques Offenbach, das Bildarchiv des Historikers Reinhart Koselleck mit Abteilungen Tausender Fotos von Reiterdenkmälern beispielsweise oder der Kasten des Romanisten Hans Robert Jauß, in dem er für seine Habilitationsschrift mittelalterliche Tiernamen und -eigenschaften verzettelte.

machine translation (Google)

Quite a few boxes have been created for just one book, Siegfried Kracauer's collections for his monograph on Jacques Offenbach, for example, the photo archive of the historian Reinhart Koselleck with sections of thousands of photos of equestrian monuments, for example, or the box by the Romanist Hans Robert Jauß, in which he wrote for his Habilitation dissertation bogged down medieval animal names and characteristics.

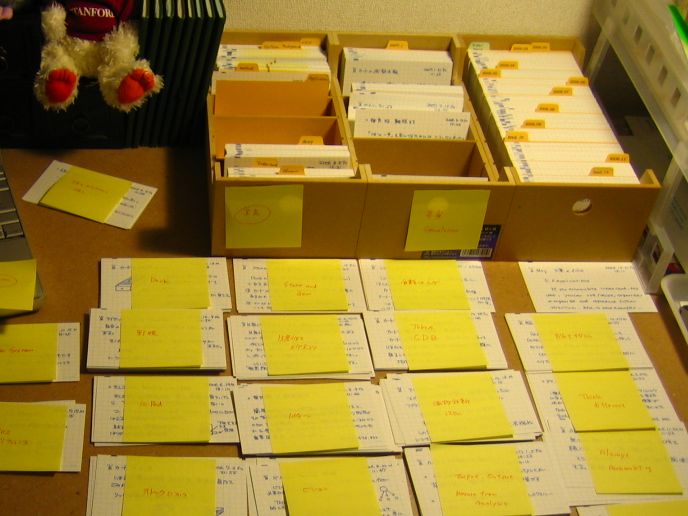

A zettelkasten need not be a lifetime practice and historically many were created for supporting a specific project or ultimate work. Examples can be seen in the work of both Robert Green and his former assistant Ryan Holiday who kept separate collections for each of their books, as well as those displayed at the German Literature Archive in Marbach (2013) including Siegfried Kracauer (for a monograph on Jacques Offenbach), Reinhart Koselleck (equestrian related photos), Hans Robert Jauß (a dissertation on medieval animal names and characteristics).

-

Blumenberg's Zettelkasten - 30,000 entries in 55 years, i.e. almost 550 per year, which is not that much - obviously served the material management for books that he had planned and the collection of documents for theses that he had in mind, without that the reading work for it was completed.

Blumenberg's Zettelkasten had 30,000 notes which he collected over 55 years averages out to 545 notes per year or roughly (presuming he worked every day) 1.5 notes per day.

Tags

- exhibitions

- Jacques Offenbach

- Hans Blumenberg

- references

- Ryan Holiday

- examples

- Reinhart Koselleck

- Hans Blumenberg's zettelkasten

- Robert Greene

- Siegfried Kracauer

- colors

- poetry

- analogies

- single project zettelkasten

- moon

- Friedrich Kittler

- thought clouds

- 2013

- tools for thought

- precipitation

- Hans Robert Jauß

- card index for writing

- read

- animal names

- zettelkasten

- notes per day

- word clouds

- ruminant machines

- German Literature Archive (Marbach)

Annotators

URL

-

-

Local file Local file

-

“Spectators come. They get to seeeverything, and nothing but that—as in an adult movie. And are accord-ingly disappointed.”16

She quotes this from a second party rather than directly from Luhmann's zettelkasten: Niklas Luhmann, Zettelkasten II, index card no. 9/8,3 see: https://hypothes.is/a/LRCMnln_EeyW_OMPTJ3JiA

16 “Zuschauer kommen. Sie bekommen alles zu sehen, und nichts als das—wie beim Pornofilm. Und entsprechend ist die Entta ̈ uschung,” as quoted in Ju ̈ rgen Kaube, “Alles und noch viel mehr: Die gelehrte Registratur,” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, March 6, 2013, http://www.faz.net/aktuell/feuilleton/geisteswissenschaften/zettelkaesten-alles-und -noch-viel-mehr-die-gelehrte-registratur-12103104.html.

-

Blumenberg’s near-obsessive reliance on this writing machinery

Helbig indicates that Hans Blumenberg had a "near obsessive reliance on [his Zettelkasten as] writing machinery.

-

Iforeground the role of his Zettelkasten as the site of developing his owntheoretical attitude as a historian and philosopher.

in Life without Toothache, Daniela K. Helbig looks at the role of Hans Blumenberg's Zettelkasten as the site of his theoretical development as a historian and philosopher.

-

Note cardshe struck through once or several times in red ink once he’d used them,then wrapped and hid away to avoid the risk of using them too often—asystem so integral to his own method of thinking and writing that it shapedhis understanding of other writers’ processes;

Hans Blumenberg had a habit of striking out note cards either once or twice in red ink as a means of indicating to himself that he had used them in his writing work. He also wrapped them up and hid them away to prevent the risk of over-using his ideas in publications.

-

There is a box stored in the German Literature Archive in Marbach, thewooden box Hans Blumenberg kept in a fireproof steel cabinet, for it con-tained his collection of about thirty thousand typed and handwritten notecards.1

Hans Blumenberg's zettelkasten of about thirty thousand typed and handwritten note cards is now kept at the German Literature Archive in Marbach. Blumenberg kept it in a wooden box which he kept in a fireproof steel cabinet.

-

-

www.markbernstein.org www.markbernstein.org

-

When I first read the Zettelkasten paper, in the late 90s, the interesting point was the physical filing system.

Mark Bernstein, the creator of Tinderbox, indicates that he read Niklas Luhmann's paper "Communicating with Slip Boxes: An Empirical Account" (1992) in the late 1990s.

-

-

agate.academy agate.academy

-

All materials available will be evaluated: Dictionaries, glossaries, and texts of a literary and non-literary nature. The slip box presently contains 1.5 million slips referring to 12 million references; the slips are supplemented by means of digital material.

Dictionnaire étymologique de l’ancien français (DEAF) is a dictionary built out of a slip box containing 1.5 million slipswith over 12 million references.

-

-

www.sub.uni-hamburg.de www.sub.uni-hamburg.de

-

https://www.sub.uni-hamburg.de/bibliotheken/projekte-der-stabi/abgeschlossene-projekte/jungius.html

-

Klassische Editionen können nur schwer die komplexe Arbeitsweise von Jungius’ abbilden und niemals alle möglichen Querverbindungen aufzeigen. Insbesondere sind thematisch zusammengehörende Stellen oft weit voneinander entfernt abgelegt worden, so dass selbst der bis auf die Ebene der kleinsten Konvolute des Bestands („Manipel“ von durchschnittlich etwa 15 Blatt Umfang) hinunterreichende gedruckte Katalog von Christoph Meinel deren Auffinden nur wenig erleichtert. Ebenso wenig sind sie in der Lage, die Rolle von Zeichnungen und Tabellen oder gar die Informationen auf den Zettelrückseiten adäquat wiederzugeben. Aufgrund dieser Besonderheiten ist der Nachlass Joachim Jungius besonders attraktiv für eine Digitalisierung.

machine translation (Google):

Classic editions can hardly depict Jungius' complex way of working and can never show all possible cross-connections. In particular, passages that belong together thematically have often been filed far apart from each other, so that even the printed catalog by Christoph Meinel, which extends down to the level of the smallest bundles of the collection (“Maniples” averaging around 15 pages in size), makes finding them only slightly easier. Nor are they able to adequately reproduce the role of drawings and tables or even the information on the backs of notes. Due to these special features, the estate of Joachim Jungius is particularly attractive for digitization.

It sounds here as if Christoph Meinel has collected and printed a catalog of Joachim Jungius' zettelkasten. (Where is this? Find a copy.) This seems particularly true as related cards could and would have been easily kept far apart from each other, and this could give us a hint as to the structural nature of his specific practice and uses of his notes.

It sounds as if Stabi is making an effort to digitize Jungius' note collection.

-

Der Nachlass ist aber nicht nur ein wissenschaftshistorisches Dokument, sondern auch wegen der Rückseiten interessant: Jungius verwendete Predigttexte und Erbauungsliteratur, Schülermitschriften und alte Briefe als Notizpapier. Zudem wurde vieles im Nachlass belassen, was ihm irgendwann einmal zugeordnet wurde, darunter eine Reihe von Manuskripten fremder Hand, z. B. zur Astronomie des Nicolaus Reimers.

machine translation (Google):

The estate is not only a scientific-historical document, but also interesting because of the back: Jungius used sermon texts and devotional literature, school notes and old letters as note paper. In addition, much was left in the estate that was assigned to him at some point, including a number of manuscripts by someone else, e.g. B. to the astronomy of Nicolaus Reimers.

In addition to the inherent value of the notes which Jungius took and which present a snapshot of the state-of-the art of knowledge for his day, there is a secondary source of value as he took his notes on scraps of paper that represent sermon texts and devotional literature, school notes, and old letters. These represent their own historical value separate from his notes.

-

Sein Nachlass umfasst u. a. Notizen zu allen wichtigen naturphilosophischen Fragen seiner Zeit und Briefwechsel mit seinen Schülern, die sich an den verschiedenen Universitäten des protestantischen Deutschlands und der Niederlande aufhielten. Er schrieb Literaturauszüge, Beobachtungsmitschriften, Vorlesungsvorbereitungen und anderes mehr auf kleine Zettel, von denen heute noch knapp 42.000 in der Stabi erhalten sind.

machine translation (Google):

His estate includes i.a. Notes on all important natural-philosophical questions of his time and correspondence with his students who stayed at the various universities in Protestant Germany and the Netherlands. He wrote excerpts from literature, observation notes, lecture preparations and other things on small pieces of paper, of which almost 42,000 are still preserved in the Stabi today.

Die Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Hamburg Carl von Ossietzky (Stabi) houses the almost 42,000 slips of paper from Joachim Jungius' lifetime collection of notes which include excerpts from his reading, observational notes, his lecture preparations, and other miscellaneous notes.

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

Does anyone else work in project-based systems instead? .t3_y2pzuu._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postBodyLink-VisitedLinkColor: #989898; }

reply to u/m_t_rv_s__n https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/y2pzuu/does_anyone_else_work_in_projectbased_systems/

Historically, many had zettelkasten which were commonplace books kept on note cards, usually categorized by subject (read: "folders" or "tags"), so you're not far from that original tradition.

Similar to your work pattern, you may find the idea of a "Pile of Index Cards" (PoIC) interesting. See https://lifehacker.com/the-pile-of-index-cards-system-efficiently-organizes-ta-1599093089 and https://www.flickr.com/photos/hawkexpress/albums/72157594200490122 (read the descriptions of the photos for more details; there was also a related, but now defunct wiki, which you can find copies of on Archive.org with more detail). This pattern was often seen implemented in the TiddlyWiki space, but can now be implemented in many note taking apps that have to do functionality along with search and tags. Similarly you may find those under Tiago Forte's banner "Building a Second Brain" to be closer to your project-based/productivity framing if you need additional examples or like-minded community. You may find that some of Nick Milo's Linking Your Thinking (LYT) is in this productivity spectrum as well. (Caveat emptor: these last two are selling products/services, but there's a lot of their material freely available online.)

Luhmann changed the internal structure of his particular zettelkasten that created a new variation on the older traditions. It is this Luhmann-based tradition that many in r/Zettelkasten follow. Since many who used the prior (commonplace-based) tradition were also highly productive, attributing output to a particular practice is wrongly placed. Each user approaches these traditions idiosyncratically to get them to work for themselves, so ignore naysayers and those with purist tendencies, particularly when they're new to these practices or aren't aware of their richer history. As the sub-reddit rules indicate: "There is no [universal or orthodox] 'right' way", but you'll find a way that is right for you.

-

-

unclutterer.com unclutterer.com

-

Brief explanation of the Pile of Index Cards system, but without significant depth.

-

-

www.flickr.com www.flickr.comkf3331

-

https://www.flickr.com/photos/36761543@N02/

Kf333 falls into the tradition of PoIC which they associated directly.

They photographed and saved their cards into Flickr.

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

Posted byu/raphaelmustermann9 hours agoSeparate private information from the outline of academic disciplines? .t3_xi63kb._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postBodyLink-VisitedLinkColor: #989898; } How does Luhmann deal with private Zettels? Does he store them in a separate category like, 2000 private. Or does he work them out under is topics in the main box.I can´ find informations about that. Anyway, you´re not Luhmann. But any suggestions on how to deal with informations that are private, like Health, Finances ... does not feel right to store them under acadmic disziplines. But maybe it´s right and just a feeling which come´ out how we "normaly" store information.

I would echo Bob's sentiment here and would recommend you keep that material like this in a separate section or box all together.

If it helps to have an example, in 2006, Hawk Sugano showed off a version of a method you may be considering which broadly went under the title of Pile of Index Cards (or PoIC) which combined zettelkasten and productivity systems (in his case getting things done or GTD). I don't think he got much (any?!) useful affordances out of mixing the two. In fact, from what I can see looking at later iterations of his work and how he used it, it almost seems like he spent more time and energy later attempting to separate and rearrange them to get use out of the knowledge portions as distinct from the productivity portions.

I've generally seen people mixing these ideas in the digital space usually to their detriment as well—a practice I call zettelkasten overreach.

-

-

zettelkasten.de zettelkasten.de

-

image courtesy hawkexpress on flickr

Interesting to see the first post on zettelkasten.de in 2013 has a photo of hawkexpress' Pile of Index Cards (PoIC) in it.

This obviously means that Christian Tietze had at least a passing familiarity with that system, though it differed structurally from Luhmann's version of zettelkasten.

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

Check out the Zettelkasten (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zettelkasten). It may be similar to what you're thinking of. I use a digital one (Foam), and it's absolutely awesome. It's totally turned how I do my work for school on its head.

reply to https://www.reddit.com/user/kf6gpe/

Thanks. Having edited large parts of that page, and particularly the history pieces, I'm aware of it. It's also why I'm asking for actual examples of practices and personal histories, especially since many in this particular forum appear to be using traditional notebook/journal forms. :)

Did you come to ZK or commonplacing first? How did you hear about it/them? Is your practice like the traditional commonplacing framing, closer to Luhmann's/that suggested by zettelkasten.de/Ahrens, or a hybrid of the two approaches?

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

Underlining Keyterms and Index Bloat .t3_y1akec._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postBodyLink-VisitedLinkColor: #989898; }

Hello u/sscheper,

Let me start by thanking you for introducing me to Zettelkasten. I have been writing notes for a week now and it's great that I'm able to retain more info and relate pieces of knowledge better through this method.

I recently came to notice that there is redundancy in my index entries.

I have two entries for Number Line. I have two branches in my Math category that deals with arithmetic, and so far I have "Addition" and "Subtraction". In those two branches I talk about visualizing ways of doing that, and both of those make use of and underline the term Number Line. So now the two entries in my index are "Number Line (Under Addition)" and "Number Line (Under Subtraction)". In those notes I elaborate how exactly each operation is done on a number line and the insights that can be derived from it. If this continues, I will have Number Line entries for "Multiplication" and "Division". I will also have to point to these entries if I want to link a main note for "Number Line".

Is this alright? Am I underlining appropriately? When do I not underline keyterms? I know that I do these to increase my chances of relating to those notes when I get to reach the concept of Number Lines as I go through the index but I feel like I'm overdoing it, and it's probably bloating it.

I get "Communication (under Info. Theory): '4212/1'" in the beginning because that is one aspect of Communication itself. But for something like the number line, it's very closely associated with arithmetic operations, and maybe I need to rethink how I populate my index.

Presuming, since you're here, that you're creating a more Luhmann-esque inspired zettelkasten as opposed to the commonplace book (and usually more heavily indexed) inspired version, here are some things to think about:<br /> - Aren't your various versions of number line card behind each other or at least very near each other within your system to begin with? (And if not, why not?) If they are, then you can get away with indexing only one and know that the others will automatically be nearby in the tree. <br /> - Rather than indexing each, why not cross-index the cards themselves (if they happen to be far away from each other) so that the link to Number Line (Subtraction) appears on Number Line (Addition) and vice-versa? As long as you can find one, you'll be able to find them all, if necessary.

If you look at Luhmann's online example index, you'll see that each index term only has one or two cross references, in part because future/new ideas close to the first one will naturally be installed close to the first instance. You won't find thousands of index entries in his system for things like "sociology" or "systems theory" because there would be so many that the index term would be useless. Instead, over time, he built huge blocks of cards on these topics and was thus able to focus more on the narrow/niche topics, which is usually where you're going to be doing most of your direct (and interesting) work.

Your case sounds, and I see it with many, is that your thinking process is going from the bottom up, but that you're attempting to wedge it into a top down process and create an artificial hierarchy based on it. Resist this urge. Approaching things after-the-fact, we might place information theory as a sub-category of mathematics with overlaps in physics, engineering, computer science, and even the humanities in areas like sociology, psychology, and anthropology, but where you put your work on it may depend on your approach. If you're a physicist, you'll center it within your physics work and then branch out from there. You'd then have some of the psychology related parts of information theory and communications branching off of your physics work, but who cares if it's there and not in a dramatically separate section with the top level labeled humanities? It's all interdisciplinary anyway, so don't worry and place things closest in your system to where you think they fit for you and your work. If you had five different people studying information theory who were respectively a physicist, a mathematician, a computer scientist, an engineer, and an anthropologist, they could ostensibly have all the same material on their cards, but the branching structures and locations of them all would be dramatically different and unique, if nothing else based on the time ordered way in which they came across all the distinct pieces. This is fine. You're building this for yourself, not for a mass public that will be using the Dewey Decimal System to track it all down—researchers and librarians can do that on behalf of your estate. (Of course, if you're a musician, it bears noting that you'd be totally fine building your information theory section within the area of "bands" as a subsection on "The Bandwagon". 😁)

If you overthink things and attempt to keep them too separate in their own prefigured categorical bins, you might, for example, have "chocolate" filed historically under the Olmec and might have "peanut butter" filed with Marcellus Gilmore Edson under chemistry or pharmacy. If you're a professional pastry chef this could be devastating as it will be much harder for the true "foodie" in your zettelkasten to creatively and more serendipitously link the two together to make peanut butter cups, something which may have otherwise fallen out much more quickly and easily if you'd taken a multi-disciplinary (bottom up) and certainly more natural approach to begin with. (Apologies for the length and potential overreach on your context here, but my two line response expanded because of other lines of thought I've been working on, and it was just easier for me to continue on writing while I had the "muse". Rather than edit it back down, I'll leave it as it may be of potential use to others coming with no context at all. In other words, consider most of this response a selfish one for me and my own slip box than as responsive to the OP.)

Tags

- information theory

- Claude Shannon

- The Bandwagon

- commonplace books vs. zettelkasten

- hierarchies

- Niklas Luhmann's index

- Niklas Luhmann's zettelkasten

- Universal Decimal Classification

- examples

- indices

- bottom-up vs. top-down

- multi-disciplinary research

- zettelkasten

- reply

- Dewey Decimal System

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.comYouTube1

-

<small><cite class='h-cite via'>ᔥ <span class='p-author h-card'>u/taurusnoises</span> in One of the ways I use my zettelkasten (though Obsidian) to write essays : Zettelkasten (<time class='dt-published'>08/10/2022 12:28:58</time>)</cite></small>

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

Apply zettelkasten at school?

Posted by u/ivanZalevskiy https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/y0k076/apply_zettelkasten_at_school/

From a historical perspective, education is broadly the reason zettelkasten principles were created and evolved. In the late 1400s and early 1500s Agricola, Erasmus, and Melanchthon wrote handbooks for students and teachers to spread these methods specifically for learning and building knowledge. Here's a reasonable example of someone using them for their Ph.D. work, and I suspect they, like many, wish they'd started sooner: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wiol2oJAh6.

I've remarked in the past that zettelkasten methods very closely mimic the various levels of Bloom's Taxonomy, which outlines broadly how people learn and grow: https://hypothes.is/a/c8jzkLHgEeyUhBs5w48csg

-

-

forum.zettelkasten.de forum.zettelkasten.de

-

<small><cite class='h-cite via'>ᔥ <span class='p-author h-card'>Will</span> in Review of “On Intellectual Craftsmanship” (1952) by C. Wright Mills — Zettelkasten Forum (<time class='dt-published'>10/04/2022 10:44:44</time>)</cite></small>

Read 2022-10-10 00:35

-

-

www.arthurperret.fr www.arthurperret.fr

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

Luhmann zettelkasten origin myth at 165 second mark

A short outline of several numbering schemes (essentially all decimal in nature) for zettelkasten including: - Luhmann's numbering - Bob Doto - Scott Scheper - Dan Allosso - Forrest Perry

A little light on the "why", though it does get location as a primary focus. Misses the idea of density and branching. Touches on but broadly misses the arbitrariness of using the comma, period, or slash which functions primarily for readability.

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

https://www.reddit.com/r/antinet/comments/xyhpq4/2015_exhibition_of_roland_barthes_zettelkasten/

Johanna Daniel has some interesting reflections (in French) about Barthes' reading, note taking, and writing processes: http://johannadaniel.fr/isidoreganesh/2015/06/archives-roland-barthes/ Perhaps most importantly she's got some photos from an exhibition of his work which includes portions of his note cards and writing. Roland Barthes' note cards on the Sorrows of Young Werther by Goethe. And you thought your makeshift cardboard boxes weren't "enough"? Want more about Barthes' practice? Try my digital notes: https://hypothes.is/users/chrisaldrich?q=tag%3A%22Roland+Barthes%22

-

-

forum.eastgate.com forum.eastgate.com

-

www.eastgate.com www.eastgate.com

-

Tinderbox

Tinderbox really is a fantastic name for a note taking / personal knowledge management system. Just the idea makes me want to paint flames on the sides of my physical card index. https://www.eastgate.com/Tinderbox/

-

-

Local file Local file

-

So there is nothing exaggerated in thinking that Barthes would havefinally found the form for these many scattered raw materials (indexcards, desk diaries, old or ongoing private diaries, current notes,narratives to come, the planned discussion of homosexuality) ifdeath had not brought his work and his reflection to an end. Thework would certainly not have corresponded to the current definitionof the novel as narration and the unfolding of a plot, but the historyof forms tells us that the word ‘novel’ has been used to designate themost diverse objects.

Just as in Jason Lustig's paper about Gotthard Deutsch's zettelkasten, here is an example of an outside observer bemoaning the idea of things not done with a deceased's corpus of notes.

It's almost like looking at the "corpus" of notes being reminiscent of the person who has died and thinking about what could have bee if they had left. It gives the impression that, "here are their ideas" or "here is their brain and thoughts" loosely connected. Almost as if they are still with us, in a way that doesn't quite exist when looking at their corpus of books.

-

Instead of imposing a ‘rational’ order on the fragments,Barthes used the ‘stupid’, arbitrary, obvious order of the alphabet(which he also most often followed when he was classifying his indexcards): this was how he proceeded in ‘Variations on Writing’ and inRoland Barthes par Roland Barthes. This was how he achieved anindividual identity, surrendering to his tastes and to concrete littleidiosyncrasies.

-

-

news.ycombinator.com news.ycombinator.com

-

Luhmann, who came up with Zettelkasten

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

Local file Local file

-

the bottom right of each card was adorned with abbreviated citations,often more than one.

The cards in Deutch's zettelkasten were well cited, typically using abbreviations which appeared in the bottom right of each card, and often with multiple citations.

-

He was especially enamored with cross-references, which weremarked in red type;

Deutch's zettelkasten is well cross-referenced and he showed a preference for doing these in red type.

-

If he initially wrote hiscards by hand, the vast majority were typewritten with Hebrew words written in blankspaces when required.

While many of Deutsch's cards were initially written by hand, the majority of them are typewritten and included blank spaces for Hebrew words when required.

-

In one way, the cards’ uniform size and format was part of Deutsch’sdream to produce a systematic method of research and writing.

-

Deutsch’s index, then, did not constitute the systematic and overarching view ofJewish history and contemporaneous Jewish issues that Deutsch had initially hoped tocreate. Instead, it was much more personal. It reflected his singular reading regime, and itworked with a certain shorthand: In later years Deutsch often just cited ‘Yiddish papers’or ‘Daily papers’, and in some instances he referred to ‘private information’. The cards,topics, and sources provide a sense of the specific information that interested Deutsch.

-

Further, very few cards areout of order, suggesting that Deutsch may not have extensively removed sets of cards toshuffle them into novel patterns, as returning them would probably have resulted in out-of-place items.

This would seem to contradict his statements about some of the orderings and chaos earlier.

One must also ask the question about use and curation of the collection following his death?

-

There is also very limited metadata. Many of the cross-references, referencing cardslike PIUS X or GERMANY, 1848, to give just two examples from this set, provoke one towander the corridors of cards searching for what Deutsch had in mind.

According to Lustig, Gotthard Deutsch's zettelkasten had limited metadata and cross-references didn't always connect to concrete endings. (p12)

This fact can help to better define the Wikipedia page on zettelkasten.

-

Further, Deutsch triedto instill a certain chronological, geographical and thematic method of organization. Butthis arrangement is also a stumbling block to anyone who might want to use it, includingDeutsch. ACCUSATIONS AGAINST THE JEWS (489 cards), for instance, presents an array ofevents organized not by date but in a surprisingly unsystematic alphabetical order. Insteadof indicating when such accusations were more or less prevalent, which could only beindicated by reorganizing cards chronologically, the default alphabetical sorting, whichshows instances in disparate locations like London (in May, 1921) alongside Sziget,Hungary (from 1867), gives the impression that such anti-Jewish events were everywhere.And even this organization was chaotic. The card on Sziget is actually listed under‘Marmaros’, the publication with which the card’s text began, and an immediately pre-ceding card is ordered based on its opening ‘A long list of accusations . . . ’, not thereference to its source: Goethe’s Das Jahrmarketsfest zu Plundersweilern.

Lustig provides a description of some of the order of Gotthard Deutsch's zettelkasten. Most of it seemed to have been organized by chronological, geographical and thematic means, but often there was chaos. This could be indicative of many things including broad organization levels, but through active use, he may have sorted and resorted cards as needs required. Upon replacing cards he may not have defaulted to some specific order relying on the broad levels and knowing what state he had left things last. Though regular use, this wouldn't concern an individual the way it might concern outsiders who may not understand the basic orderings (as did Lustig) or be able to discern and find things as quickly as he may have been able to.

-

one recognizes in the tactile realitythat so many of the cards are on flimsy copy paper, on the verge of disintegration with eachuse.

Deutsch used flimsy copy paper, much like Niklas Luhmann, and as a result some are on the verge of disintegration through use over time.

The wear of the paper here, however, is indicative of active use over time as well as potential care in use, a useful historical fact.

-

All this was listed in alphabetical and chronological order over a total of about 50boxes,

Deutsch's zettelkasten consisted of about 50 boxes and was done in alphabetical and chronological order.

-

Altogether, one finds an interminable assortment of facts on almost anytopic, with major sections relating to blood accusations and blood libels, fiction andliterature, the Passover Haggadah, memoirs, mixed marriages, orthodoxy, Palestine,periodicals, and universities, but also obscure topics including hunting, Russian Jewishdwarfs, and myths and magic.

Deutsch's zettelkasten seems to have been done in index style using headwords as was common in the older commonplace tradition.

-

He sometimes pasted newsprint cuttings to present a statistical chart or inserted

a photograph.

Deutsch's zettelkasten has a variety of patterns including cuttings from newspapers, photos, excerpts, some were handwritten while others were typed, (and some showing many of these all at once!).

-

Examining the cards, it becomes clear that the index constitutes not a mythic totalhistory but a specific set of facts and data that piqued Deutsch’s interest and whichreflected his personal research priorities (see Figure 2).

Zettelkasten, if nothing else, are a close reflection of the interests of the author who collected them.

link: Ahrens mentions this

-

If in 1908 itcontained 10,000 cards, by 1917 it had ballooned in size to 50,000 items, reaching60,000 in 1919 and nearly 70,000 at the time of Deutsch’s death in 1921 (Deutsch,1908b, 1917b; Brown, 1919: 69). It seems that Deutsch consistently produced 5,000cards per year (about 20 per workday) for the final 13 years of his life.

Look up these references to confirm scope of numbers.

-

e called on his fellow rabbis to submitnotecards with details from their readings. He proposed that a central office gathermaterial into a ‘system’ of information about Jewish history, and he suggested theypublish the notes in the CCAR’s Yearbook.

This sounds similar to the variety of calls to do collaborative card indexes for scientific efforts, particularly those found in the fall of 1899 in the journal Science.

This is also very similar to Mortimer J. Adler et al's group collaboration to produce The Syntopicon as well as his work on Propædia and Encyclopædia Britannica.

-

Deutsch’s focus on facts was commonplace among professional US historians atthis time, as was his conception of the ‘fact’ as a small item that could fit onto the sizeof an index card (Daston, 2002).

Find this quote and context!

-

Deutsch created his index in the context of a range of encyclopedic activities. In 1897,the Central Conference of American Rabbis asked Deutsch to create a two-volume ency-clopedia, and he soon joined a similar effort by Funk and Wagnalls under the direction ofIsidore Singer. As the main editor for historical topics, Deutsch helped publish 12 volumesof the Jewish Encyclopedia from 1901 to 1906. In these same years, Deutsch produced acalendar of Jewish anniversaries in the monthly Die Deborah (1901), reprinted in 1904 inthe Hebrew Union College Annual (as the ‘Encyclopedic Department’) and as a standalonevolume (Deutsch, 1904a, 1904b).

Deutsch's encyclopedia work here sounds similar to that of Mortimer J. Adler who used a card index in much the same way.

-

Colleagues made a similarmove by calling Deutsch a ‘bor sud she-’eino me-’abed t.ippah’, a ‘cistern that neverloses a drop’. This oft-repeated designation simultaneously linked him to the

first-century rabbi Eliezer ben Hyrcanus (Mishnah Avot 2:9) and alluded to what some termed on other occasions his ‘marvelous memory for detail’, ‘encyclopedic mind’, or ‘inexhaustible stores of memory’ that allowed him to furnish his ‘convincing array of facts’ 5 (Heller, 1916; L. F., 1919; Mendelsohn, 1916; Schulman, 1922; Stolz, 1921). However, it was perhaps not Deutsch himself who was a ‘cistern’ but instead his card catalogue where he stored drops of data growing to a sea of erudition and which served as a prosthesis for his legendary recall (see Figure 1).

While the practice with his zettelkasten may have been helpful, it's quite likely that given these quotes about his memory that they're evidence of the use of the major system which would have been quite popular and well known at his time, but which isn't now.

The author is going to need to provide evidence one way or another, but I suspect they're not aware of the mnemonic traditions of the time to make the opposite case.

-

‘He knows everything that’s happened fromB’reshis [Genesis] to today’, it went, ‘and it really isn’t work to him – it’s merely play’,a sentiment later expressed when one colleague wrote of Deutsch’s ‘game of cards’(Margolis, 1921).3

Apparently a colleague wrote about Deutsch's "game of cards" as a description of hit use of a zettelkasten. The play here is reminiscent of the joy Ahrens talks about when doing research/reading/writing (2017).

-

Consequently, instead of a curiousbut otherwise useless exercise and a delusional preoccupation with accumulating indi-vidual facts, closer examination shows that Deutsch’s index represented a certainforward-facing openness to new ways of managing information, and instead of theephemera of an obscure and mostly forgotten scholar, one finds a project with surpris-ingly far-reaching repercussions.

Lustig is calling an academic zettelkasten a "useless exercise" and a "delusional preoccupation"!! He also indicates that it "represented a certain forward-facing openness to new ways of managing information", something which is patently wrong within the history of information.

-

Scholem’s, given their own reading room at the National Library of Israel.

Hebrew University Jewish mysticism scholar Gershom Scholem's zettelkasten has its own reading room at the National Library of Israel.

Gershom Scholem (1897-1982)

-

eutsch suggestedthat personal memory was untrustworthy and admitted it was no match for the writtenword, and his index enabled him to store information in a way recalling Derrida’sdiscussion of archives as prostheses of memory (Derrida, 1995).

-

Walter Benjamin termed the book ‘an outdated mediationbetween two filing systems’

reference for this quote? date?

Walter Benjamin's fantastic re-definition of a book presaged the invention of the internet, though his instantiation was as a paper based machine.

-

A monument to the temple of truth taken to an illogical extreme, it might seemplainly outmoded.

It would seem that Lustig is calling the practice of keeping a zettelkasten as an "illogical extreme" and "plainly outmoded".

(His reference to "illogical extreme" may be a referent to the truth portion, but "outmoded" can only refer to the zettelkasten itself as applying that to truth either then or now just doesn't track.)

-

The index frames a figure who may at first glanceseem a curious or even comedic caricature of a certain positivist historical tradition, butone who also imparted to his students a sense of the magnitude of Jewish history, andwho straddled a mechanical pursuit of individual ‘facts’ with a certain attention to novelmethods and visions of comprehensively encyclopedic information.

From where did Deutsch learn his zettelkasten method? And when? Bernheim's influential Lehrbuch der historischen Methode (1889) was published long after Deutsch entered seminary in October 1876 and 9 years before he received his Ph.D. in history in1881.

One must potentially posit that the zettelkasten method was being passed along in (at least history circles) long before Bernheim's publication.

I'm hoping that Lustig isn't referring to zettelkasten when he says "novel methods", as they weren't novel, even at that time. Deutsch certainly wasn't the first to have comprehensive encyclopedic visions, as Zettelkasten practitioner Konrad Gessner preceded him by several centuries.

I'm starting to severely question Lustig's familiarity with these particular traditions....

-

Without fail, obituaries commented on theindex and declared the colossal Zettelkasten either a great gift to scholarship or alter-nately ‘mere chips from his workshop’, which marked an exceptional effort but ultimateinability to look beyond the details. 1

Gotthard Deutsch, Divine and Writer, Dies of Pneumonia’, 21 Oct. 1921, American Jewish Archives (AJA), Cincinnati, OH, MS-123 Oversize Box 313; Chicago Rabbinical Association, ‘Gotthard Deutsch Memorial Resolutions’, 31 Oct. 1921, AJA MS-123 1/17.

An obituary calling a Zettelkasten "mere chips from his workshop" seems more indicative of the lack of knowledge of what one is and how it is used than a historian of information or academic with knowledge of the tradition calling it such.

This quote from 1921 is also broadly indicative of the potential fact that the idea of zettelkasten for academic use was not widely known by the general public, if in fact, it ever had been.

-

This imposing cabinetof curiosities

Is it appropriate to call a zettelkasten of 70,000 a "cabinet of curiosities"? They really are dramatically different forms of media, though a less discerning modern viewer might conflate the two to make a comparison.

Tags

- definitions

- citations

- examples

- zettelkasten are idiosyncratic

- Syntopicon

- facts

- 1921

- encyclopedias

- Hebrew University

- open questions

- orderings

- card Centralblatt

- zettelkasten as mnemonic device

- card stock

- zettelkasten popularity

- archives

- chronological order

- alphabetization

- Encyclopædia Britannica

- Konrad Gessner

- cards of equal size

- Jacques Derrida

- rubrication

- handwriting vs. typing

- Propædia

- 1899

- index cards

- zettelkasten

- major system

- notes per day

- cross references

- collaborative zettelkasten

- curiosity cabinets

- topical headings

- group notes

- prostheses

- Gotthard Deutsch's zettelkasten

- Science

- Walter Benjamin

- Mortimer J. Adler

- Sönke Ahrens

- collaborative note taking

- zettelkasten misconceptions

- ars excerpendi

- networked commonplace books

- paper data storage

- Internet

- personal interests

- Jewish mysticism

- disintegration

- Gershom Scholem

- National Library of Israel

- zettelkasten vs. curiosity cabinets

- intellectual history

- quotes

- card index as autobiography

- metadata

- indices

- books

- material culture

- Gotthard Deutsch

- geographical order

- euphemisms

- game of cards

Annotators

-

-

journals.sagepub.com journals.sagepub.com

-

Adams H. B. (1886) Methods of Historical Study. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University.

Where does this fit with respect to the zettelkasten tradition and Bernheim, Langlois/Seignobos?

-

Indeed, Deutsch’s index is massive but middling, especially when placed alongside those of Niklas Luhmann, Paul Otlet, or Gershom Scholem.

Curious how Deutsch's 70,000 facts would be middling compared to Luhmann's 90,000? - How many years did Deutsch maintain and collect his version?<br /> - How many publications did he contribute to? - Was his also used for teaching?

Otlet didn't create his collection alone did he? Wasn't it a massive group effort?

Check into Gershom Scholem's collection and use. I've not come across his work in this space.

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

Anyone doing NaNoWriMo!?

I posted a follow up question in the NaNoWriMo forum, which may get some additional traction: https://forums.nanowrimo.org/t/linking-up-zettelkasten-or-card-index-method-writers/433719

I'm more of a "pantser" (vs planner) when it comes to NaNoWriMo, but if you think about it, zettelkasten provides a solid structure that builds your plan for you as you go.

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

Posted byu/lsumnler1 year agoHow is a commonplace book different than a zettelkasten? .t3_pguxq7._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postBodyLink-VisitedLinkColor: #989898; } I get that physically the commonplace book is in a notebook whether physical or digitized and zettelkasten is in index cards whether physical or digitized but don't they server the same purpose.

Broadly the zettelkasten tradition grew out of commonplacing in the 1500s, in part, because it was easier to arrange and re-arrange one's thoughts on cards for potential reuse in outlining and writing. Most zettelkasten are just index card-based forms of commonplaces, though some following Niklas Luhmann's model have a higher level of internal links, connections, and structure.

I wrote a bit about some of these traditions (especially online ones) a while back at: https://boffosocko.com/2021/07/03/differentiating-online-variations-of-the-commonplace-book-digital-gardens-wikis-zettlekasten-waste-books-florilegia-and-second-brains/

-

-

archive.org archive.org

-

https://archive.org/details/refiningreadingw0000meij/page/256/mode/2up?q=index+card

Refining, reading, writing : includes 2009 mla update card by Mei, Jennifer (Nelson, 2007)

Contains a very generic reference to note taking on index cards for arranging material, but of such a low quality in comparison to more sophisticated treatments in the century prior. Apparently by this time the older traditions have disappeared and have been heavily watered down into just a few paragraphs.

-

-

Local file Local file

-

Cattell, J. McKeen. “Methods for a Card Index.” Science 10, no. 247 (1899): 419–20.

Columbia professor of psychology calls for the creation of a card index of references to reviews and abstracts for areas of research. Columbia was apparently doing this in 1899 for the psychology department.

What happened to this effort? How similar was it to the system of advertising cards for books in Germany in the early 1930s described by Heyde?

-

-

www.jstor.org www.jstor.org

-

Teatr Maly - Kartoteka - Rozewicz (The Card File by Rozewicz, Maly Theater)Creatordesigner: Maciej Urbaniec (Polish, 1925-2004)

-

-

archive.org archive.org

-

Goutor doesn't specifically cover the process, but ostensibly after one has categorized content notes, they are filed together in one's box under that heading. (p34) As a result, there is no specific indexing or cross-indexing of cards or ideas which might be filed under multiple headings. In fact, he doesn't approach the idea of filing under multiple headings at all, while authors like Heyde (1931) obsess over it. Goutor's method also presumes that the creation of some of the subject headings is to be done in the planning stages of the project, though in practice some may arise as one works. This process is more similar to that seen in Robert Greene's commonplacing method using index cards.

-

Thesis to bear out (only tangentially related to this particular text):

Part of the reason that index card files didn't catch on, especially in America, was that they didn't have a solid/concrete name by which they went. The generic term card index subsumed so much in relation to library card catalogues or rolodexes which had very specific functions and individualized names. Other cultures had more descriptive names like zettelkasten or fichier boîte which, while potentially bland within their languages, had more specific names for what they were.

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

level 1coluseum · 14 hr. agoInteresting to be sure! But feel it misses the whole point , in my opinion, of building your own ….if you just buy someone’s else’s then where are your original thoughts and ideas…..those will be in built in your own zettlekasten….sort of the whole point in my eyes? I think one of the sticking points with zettlekasten is the amount of time and effort it can take and so people will try and short circuit the process . The point to me is the process of building your own original zettlekasten is the whole point. Hope I am making sense 😗

I get the gist of what you're saying and I prefer putting things into my own collection in my own words as well. However, there is a history of folks putting other materials into their systems like this. Johannes Heyde, in particular, mentioned that German publishers used to mail promo details for forthcoming books on A6 size postcards that one might place directly into their bibliographic index without needing to recopy.

I know I've suggested to u/sscheper before that he ought to release his forthcoming book in index card format, if only as an interesting means of showing an example of what a zettelkasten looks like and how it might work.

-

level 1tristanjuricek · 4 hr. agoI’m not sure I see these products as anything more than a way for middle management to put some structure behind meetings, presentations, etc in a novel format. I’m not really sure this is what I’d consider a zettlecasten because there’s really no “net” here; no linking of information between cards. Just some different exercises.If you actually look at some of the cards, they read more like little cues to drive various processes forward: https://pipdecks.com/products/workshop-tactics?variant=39770920321113I’m pretty sure if you had 10 other people read those books and analyze them, they’d come up with 10 different observations on these topics of team management, presentation building, etc.

Historically the vast majority of zettelkasten didn't have the sort of structure and design of Luhmann's, though with indexing they certainly create a network of notes and excerpts. These examples are just subsets or excerpts of someone's reading of these books and surely anyone else reading any book is going to have a unique set of notes on them. These sets were specifically honed and curated for a particular purpose.

The interesting pattern here is that someone is selling a subset of their work/notes as a set of cards rather than as a book. Doing this allows different sorts of reading and uses than a "traditional" book would.

I'm curious what other sort of experimental things people might come up with? The "novel" Cain's Jawbone, for example, could be considered a "Zettelkasten mystery" or "Zettelkasten puzzle". There's also the subset of cards from Roland Barthes' fichier boîte (French for zettelkasten), which was published posthumously as Mourning Diary.

-

I saw this ad for Storyteller Tactics on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/p/CiybhKcA3ZV/?hl=en. The pitchman indicates that he distilled down a pile of about 25 books into a deck of informative cards which writers can use in their craft. Rather than sell it as a stand alone book, it's a set of cards (in digital format too) that they're selling for a order of magnitude more than they could have gotten for a book format.

They're advertising for a product from https://pipdecks.com/. They're essentially selling custom zettelkasten collections of cards for niche topics! Who else is going to sell sets of cards like this? Anyone else seen examples of zettelkasten-like products like this?

-

-

Local file Local file

-

In "On Intellectual Craftsmanship" (1952), C. Wright Mills talks about his methods for note taking, thinking, and analysis in what he calls "sociological imagination". This is a sociologists' framing of their own research and analysis practice and thus bears a sociological related name. While he talks more about the thinking, outlining, and writing process rather than the mechanical portion of how he takes notes or what he uses, he's extending significantly on the ideas and methods that Sönke Ahrens describes in How to Take Smart Notes (2017), though obviously he's doing it 65 years earlier. It would seem obvious that the specific methods (using either files, note cards, notebooks, etc.) were a bit more commonplace for his time and context, so he spent more of his time on the finer and tougher portions of the note making and thinking processes which are often the more difficult parts once one is past the "easy" mechanics.

While Mills doesn't delineate the steps or materials of his method of note taking the way Beatrice Webb, Langlois & Seignobos, Johannes Erich Heyde, Antonin Sertillanges, or many others have done before or Umberto Eco, Robert Greene/Ryan Holiday, Sönke Ahrens, or Dan Allosso since, he does focus more on the softer portions of his thinking methods and their desired outcomes and provides personal examples of how it works and what his expected outcomes are. Much like Niklas Luhmann describes in Kommunikation mit Zettelkästen (VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 1981), Mills is focusing on the thinking processes and outcomes, but in a more accessible way and with some additional depth.

Because the paper is rather short, but specific in its ideas and methods, those who finish the broad strokes of Ahrens' book and methods and find themselves somewhat confused will more than profit from the discussion here in Mills. Those looking for a stronger "crash course" might find that the first seven chapters of Allosso along with this discussion in Mills is a straighter and shorter path.

While Mills doesn't delineate his specific method in terms of physical tools, he does broadly refer to "files" which can be thought of as a zettelkasten (slip box) or card index traditions. Scant evidence in the piece indicates that he's talking about physical file folders and sheets of paper rather than slips or index cards, but this is generally irrelevant to the broader process of thinking or writing. Once can easily replace the instances of the English word "file" with the German concept of zettelkasten and not be confused.

One will note that this paper was written as a manuscript in April 1952 and was later distributed for classroom use in 1955, meaning that some of these methods were being distributed from professor to students. The piece was later revised and included as an appendix to Mill's text The Sociological Imagination which was first published in 1959.

Because there aren't specifics about Mills' note structure indicated here, we can't determine if his system was like that of Niklas Luhmann, but given the historical record one could suppose that it was closer to the commonplace tradition using slips or sheets. One thing becomes more clear however that between the popularity of Webb's work and this (which was reprinted in 2000 with a 40th anniversary edition), these methods were widespread in the mid-twentieth century and specifically in the field of sociology.

Above and beyond most of these sorts of treatises on note taking method, Mills does spend more time on the thinking portions of the practice and delineates eleven different practices that one can focus on as they actively read/think and take notes as well as afterwards for creating content or writing.

My full notes on the article can be found at https://jonudell.info/h/facet/?user=chrisaldrich&max=100&exactTagSearch=true&expanded=true&addQuoteContext=true&url=urn%3Ax-pdf%3A0138200b4bfcde2757a137d61cd65cb8

-

As I thus rearranged the filing system, I found that I wasloosening my imagination.

"loosening my imagination" !!

-

Use of File

It bears pointing out that Mills hasn't specifically described the form of his "file". Is he using note cards, slips, sheets of paper? Ostensibly one might suppose given his context and the word "file" which he uses that he may be referring to either hanging files, folders, and sheets of paper, or a more traditional index card file.

-

nd the way in which these cate-gories changed, some being dropped out and others beingadded, was an index of my own intellectual progress andbreadth. Eventually, the file came to be arranged accord-ing to several larger projects, having many subprojects,which changed from year to year.

In his section on "Arrangement of File", C. Wright Mills describes some of the evolution of his "file". Knowing that the form and function of one's notes may change over time (Luhmann's certainly changed over time too, a fact which is underlined by his having created a separate ZK II) one should take some comfort and solace that theirs certainly will as well.

The system designer might also consider the variety of shapes and forms to potentially create a better long term design of their (or others') system(s) for their ultimate needs and use cases. How can one avoid constant change, constant rearrangement, which takes work? How can one minimize the amount of work that goes into creating their system?

The individual knowledge worker or researcher should have some idea about the various user interfaces and potential arrangements that are available to them before choosing a tool or system for maintaining their work. What are the affordances they might be looking for? What will minimize their overall work, particularly on a lifetime project?

-

A personal file is thesocial organization of the individual's memory; it in-creases the continuity between life and work, and it per-mits a continuity in the work itself, and the planning of thework; it is a crossroads of life experience, professionalactivities, and way of work. In this file the intellectualcraftsman tries to integrate what he is doing intellectuallyand what he is experiencing as a person.

Again he uses the idea of a "file" which I read and understand as similar to the concepts of zettelkasten or commonplace book. Unlike others writing about these concepts though, he seems to be taking a more holistic and integrative (life) approach to having and maintaining such system.

Perhaps a more extreme statement of this might be written as "zettelkasten is life" or the even more extreme "life is zettelkasten"?

Is his grounding in sociology responsible for framing it as a "social organization" of one's memory?

It's not explicit, but this statement could be used as underpinning or informing the idea of using a card index as autobiography.

How does this compare to other examples of this as a function?

-

In the file, onecan experiment as a writer and thus develop o n e ' s ownpowers of expression.

-

To be able to trustone's own experience, even if it often turns out to beinadequate, is one mark of the mature workman. Suchconfidence in o n e ' s own experience is indispensable tooriginality in any intellectual pursuit, and the file is onetool by which I have tried to develop and justify suchconfidence.

The function of memory served by having written notes is what allows the serious researcher or thinker to have greater confidence in their work, potentially more free from cognitive bias as one idea can be directly compared and contrasted with another by direct juxtaposition.

Tags

- Umberto Eco

- zettelkasten design

- files

- cognitive bias

- Sönke Ahrens

- zettelkasten affordances

- index card files

- rhetoric

- Charles Seignobos

- note taking why

- zettelkasten and memory

- social organization

- confidence

- juxtaposition

- idea links

- C. Wright Mills

- note taking affordances

- maximizing efficiency

- review

- Heyde's zettelkasten method

- evolution of knowledge

- Beatrice Webb

- quotes

- card index as autobiography

- Niklas Luhmann's zettelkasten

- tools for thought

- card index as writing teacher

- Johannes Erich Heyde

- Charles Victor Langlois

- imagination

- card index

- zettelkasten

- social order

- card index for writing

- combinatorial creativity

- minimizing work

Annotators

-

-

www.instagram.com www.instagram.com

-

Saw this ad for Storyteller Tactics on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/p/CiybhKcA3ZV/?hl=en

They're advertising for a product from https://pipdecks.com/. They're essentially selling custom zettelkasten collections of cards for niche topics!

-

- Sep 2022

-

www.seanlawson.net www.seanlawson.net

-

https://www.seanlawson.net/2017/09/zettelkasten-researchers-academics/

Hadn't heard of Mills before, but it looks interesing: C. Wright Mills, On Intellectual Craftsmanship, from The Sociological Imagination. Oxford University Press. 1960.

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wRssjvU2d-s

Starts out with some of the personal histories of how both got into the note making space.

This got more interesting for me around the 1:30 hour mark, but I was waiting for the material that would have shown up at the 3 hour mark (which doesn't exist...).

Scott spoke about the myths of zettelkasten. See https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/urawkd/the_myths_of_zettelkasten/

He also mentions maintenance rehearsal versus elaborative rehearsal. These are both part of spaced repetition. The creation of one's own cards helps play into both forms.

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

Posted byu/sscheper4 hours agoHelp Me Pick the Antinet Zettelkasten Book Cover Design! :)

I agree with many that the black and red are overwhelming on many and make the book a bit less approachable. Warm tones and rich wooden boxes would be more welcome. The 8.5x11" filing cabinets just won't fly. I did like some with the drawer frames/pulls, but put a more generic idea in the frame (perhaps "Ideas"?). From the batch so far, some of my favorites are #64 TopHills, #21 & #22 BigPoints, #13, 14 D'Estudio. Unless that pull quote is from Luhmann or maybe Eco or someone internationally famous, save it for the rear cover or maybe one of the inside flaps. There's an interesting and approachable stock photo I've been sitting on that might work for your cover: Brain and ZK via https://www.theispot.com/stock/webb. Should be reasonably licensable and doesn't have a heavy history of use on the web or elsewhere.

-

-

thevoroscope.com thevoroscope.com

-

thevoroscope.com thevoroscope.com

-

-

But even if onewere to create one’s own classification system for one’s special purposes, or for a particularfield of sciences (which of course would contradict Dewey’s claim about general applicabilityof his system), the fact remains that it is problematic to press the main areas of knowledgedevelopment into 10 main areas. In any case it seems undesirable having to rely on astranger’s

imposed system or on one’s own non-generalizable system, at least when it comes to the subdivisions.

Heyde makes the suggestion of using one's own classification system yet again and even advises against "having to rely on a stranger's imposed system". Does Luhmann see this advice and follow its general form, but adopting a numbering system ostensibly similar, but potentially more familiar to him from public administration?

-

It is obvious that due to this strict logic foundation, related thoughts will not be scattered allover the box but grouped together in proximity. As a consequence, completely withoutcarbon-copying all note sheets only need to be created once.

In a break from the more traditional subject heading filing system of many commonplacing and zettelkasten methods, in addition to this sort of scheme Heyde also suggests potentially using the Dewey Decimal System for organizing one's knowledge.

While Luhmann doesn't use Dewey's system, he does follow the broader advice which allows creating a dense numbering system though he does use a different numbering scheme.

-

The layout and use of the sheet box, as described so far, is eventually founded upon thealphabetical structure of it. It should also be mentioned though

that the sheetification can also be done based on other principles.

Heyde specifically calls the reader to consider other methods in general and points out the Dewey Decimal Classification system as a possibility. This suggestion also may have prompted Luhmann to do some evolutionary work for his own needs.

-

re all filed at the same locatin (under “Rehmke”) sequentially based onhow the thought process developed in the book. Ideally one uses numbers for that.

While Heyde spends a significant amount of time on encouraging one to index and file their ideas under one or more subject headings, he address the objection:

“Doesn’t this neglect the importance of sequentiality, context and development, i.e. doesn’t this completely make away with the well-thought out unity of thoughts that the original author created, when ideas are put on individual sheets, particularly when creating excerpts of longer scientific works?"

He suggests that one file such ideas under the same heading and then numbers them sequentially to keep the original author's intention. This might be useful advice for a classroom setting, but perhaps isn't as useful in other contexts.

But for Luhmann's use case for writing and academic research, this advice may actually be counter productive. While one might occasionally care about another author's train of thought, one is generally focusing on generating their own train of thought. So why not take this advice to advance their own work instead of simply repeating the ideas of another? Take the ideas of others along with your own and chain them together using sequential numbers for your own purposes (publishing)!!

So while taking Heyde's advice and expand upon it for his own uses and purposes, Luhmann is encouraged to chain ideas together and number them. Again he does this numbering in a way such that new ideas can be interspersed as necessary.

-

For instance, particular insights related to the sun or the moon may be filed under the(foreign) keyword “Astronomie” [Astronomy] or under the (German) keyword “Sternkunde”[Science of the Stars]. This can happen even more easily when using just one language, e.g.when notes related to the sociological term “Bund” [Association] are not just filed under“Bund” but also under “Gemeinschaft” [Community] or “Gesellschaft” [Society]. Againstthis one can protect by using dictionaries of synonyms and then create enough referencesheets (e.g. Astronomy: cf. Science of the Stars)

related, but not drawn from as I've been thinking about the continuum of taxonomies and subject headings for a while...

On the Spectrum of Topic Headings in note making

Any reasonable note one may take will likely have a hierarchical chain of tags/subject headings/keywords going from the broad to the very specific. One might start out with something broad like "humanities" (as opposed to science), and proceed into "history", "anthropology", "biological anthropology", "evolution", and even more specific. At the bottom of the chain is the specific atomic idea on the card itself. Each of the subject headings helps to situate the idea and provide the context in which it sits, but how useful within a note taking system is having one or more of these tags on it? What about overlaps with other broader subjects (one will note that "evolution" might also sit under "science" / "biology" as well), but that note may have a different tone and perspective than the prior one.

This becomes an interesting problem or issue as one explores ideas in a pre-designed note taking system. As a student just beginning to explore anthropology, one may tag hundreds of notes with anthropology to the point that the meaning of the tag is so diluted that a search of the index becomes useless as there's too much to sort through underneath it. But as one continues their studies in the topic further branches and sub headings will appear to better differentiate the ideas. This process will continue as the space further differentiates. Of course one may continue their research into areas that don't have a specific subject heading until they accumulate enough ideas within that space. (Take for example Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky's work which is now known under the heading of Behavioral Economics, a subject which broadly didn't exist before their work.) The note taker might also leverage this idea as they tag their own work as specifically as they might so as not to pollute their system as it grows without bound (or at least to the end of their lifetime).

The design of one's note taking system should take these eventualities into account and more easily allow the user to start out broad, but slowly hone in on direct specificity.

Some of this principle of atomicity of ideas and the growth from broad to specific can be seen in Luhmann's zettelkasten (especially ZK II) which starts out fairly broad and branches into the more specific. The index reflects this as well and each index heading ideally points to the most specific sub-card which begins the discussion of that particular topic.

Perhaps it was this narrowing of specificity which encouraged Luhmann to start ZKII after years of building ZKII which had a broader variety of topics?

-

If a more extensive note has been put on several A6 sheets subsequently,

Heydes Overbearing System

Heyde's method spends almost a full page talking about what to do if one extends a note or writes longer notes. He talks about using larger sheets of paper, carbon copies, folding, dating, clipping, and even stapling.

His method seems to skip the idea of extending a particular card of potentially 2 or more "twins"/"triplets"/"quadruplets" which might then also need to be extended too. Luhmann probably had a logical problem with this as tracking down all the originals and extending them would be incredibly problematic. As a result, he instead opted to put each card behind it's closest similar idea (and number it thus).

If anything, Heyde's described method is one of the most complete of it's day (compare with Bernheim, Langlois/Seignobos, Webb, Sertillanges, et al.) He discusses a variety of pros and cons, hints and tips, but he also goes deeper into some of the potential flaws and pitfalls for the practicing academic. As a result, many of the flaws he discusses and their potential work arounds (making multiple carbon copies, extending notes, etc.) add to the bulk of the description of the system and make it seem almost painful and overbearing for the affordances it allows. As a result, those reading it with a small amount of knowledge of similar traditions may have felt that there might be a better or easier system. I suspect that Niklas Luhmann was probably one of these.

It's also likely that due to these potentially increasing complexities in such note taking systems that they became to large and unwieldly for people to see the benefit in using. Combined with the emergence of the computer from this same time forward, it's likely that this time period was the beginning of the end for such analog systems and experimenting with them.

-

Who can say whether I will actually be searchingfor e.g. the note on the relation between freedom of will and responsibility by looking at itunder the keyword “Verantwortlichkeit” [Responsibility]? What if, as is only natural, I willbe unable to remember the keyword and instead search for “Willensfreiheit” [Freedom ofWill] or “Freiheit” [Freedom], hoping to find the entry? This seems to be the biggestcomplaint about the entire system of the sheet box and its merit.

Heyde specifically highlights that planning for one's future search efforts by choosing the right keyword or even multiple keywords "seems to be the biggest complaint about the entire system of the slip box and its merit."

Niklas Luhmann apparently spent some time thinking about this, or perhaps even practicing it, before changing his system so that the issue was no longer a problem. As a result, Luhmann's system is much simpler to use and maintain.

Given his primary use of his slip box for academic research and writing, perhaps his solution was in part motivated by putting the notes and ideas exactly where he would both be able to easily find them, but also exactly where he would need them for creating final products in journal articles and books.

-

For the sheets that are filled with content on one side however, the most most importantaspect is its actual “address”, which at the same time gives it its title by which it can alwaysbe found among its comrades: the keyword belongs to the upper row of the sheet, as thegraphic shows.

With respect to Niklas Luhmann's zettelkasten, it seems he eschewed the Heyde's advice to use subject headings as the Anschrift (address). Instead, much like a physical street address or card card catalog system, he substituted a card address instead. This freed him up from needing to copy cards multiple times to insert them in different places as well as needing to create multiple cards to properly index the ideas and their locations.

Without this subtle change Luhmann's 90,000 card collection could have easily been 4-5 times its size.

-

More important is the fact that recently some publishershave started to publish suitable publications not as solid books, but as file card collections.An example would be the Deutscher Karteiverlag [German File Card Publishing Company]from Berlin, which published a “Kartei der praktischen Medizin” [File Card of PracticalMedicine], published unter the co-authorship of doctors like R.F. Weiß, 1st edition (1930ff.).Not to be forgotten here is also: Schuster, Curt: Iconum Botanicarum Index, 1st edition,Dresden: Heinrich 1926

As many people used slip boxes in 1930s Germany, publishers sold texts, not as typical books, but as file card collections!

Link to: Suggestion that Scott Scheper publish his book on zettelkasten as a zettelkasten.

-

The rigidness and immobility of the note book pages, based on the papern stamp andimmobility of the individual notes, prevents quick and time-saving retrieval and applicationof the content and therefore proves the note book process to be inappropriate. The only tworeasons that this process is still commonly found in the studies of many is that firstly they donot know any better, and that secondly a total immersion into a very specialized field ofscientific research often makes information retrieval easier if not unnecessary.

Just like Heyde indicated about the slip box note taking system with respect to traditional notebook based systems in 1931, one of the reasons we still aren't broadly using Heyde's system is that we "do not know any better". This is compounded with the fact that the computer revolution makes information retrieval much easier than it had been before. However there is such an information glut and limitations to search, particularly if it's stored in multiple places, that it may be advisable to go back to some of these older, well-tried methods.

Link to ideas of "single source" of notes as opposed to multiple storage locations as is seen in social media spaces in the 2010-2020s.

-

Many know from their own experience how uncontrollable and irretrievable the oftenvaluable notes and chains of thought are in note books and in the cabinets they are stored in

Heyde indicates how "valuable notes and chains of thought are" but also points out "how uncontrollable and irretrievable" they are.

This statement is strong evidence along with others in this chapter which may have inspired Niklas Luhmann to invent his iteration of the zettelkasten method of excerpting and making notes.

(link to: Clemens /Heyde and Luhmann timeline: https://hypothes.is/a/4wxHdDqeEe2OKGMHXDKezA)

Presumably he may have either heard or seen others talking about or using these general methods either during his undergraduate or law school experiences. Even with some scant experience, this line may have struck him significantly as an organization barrier of earlier methods.

Why have notes strewn about in a box or notebook as Heyde says? Why spend the time indexing everything and then needing to search for it later? Why not take the time to actively place new ideas into one's box as close as possibly to ideas they directly relate to?