So very few modern sources describe annotation or note taking in these terms.

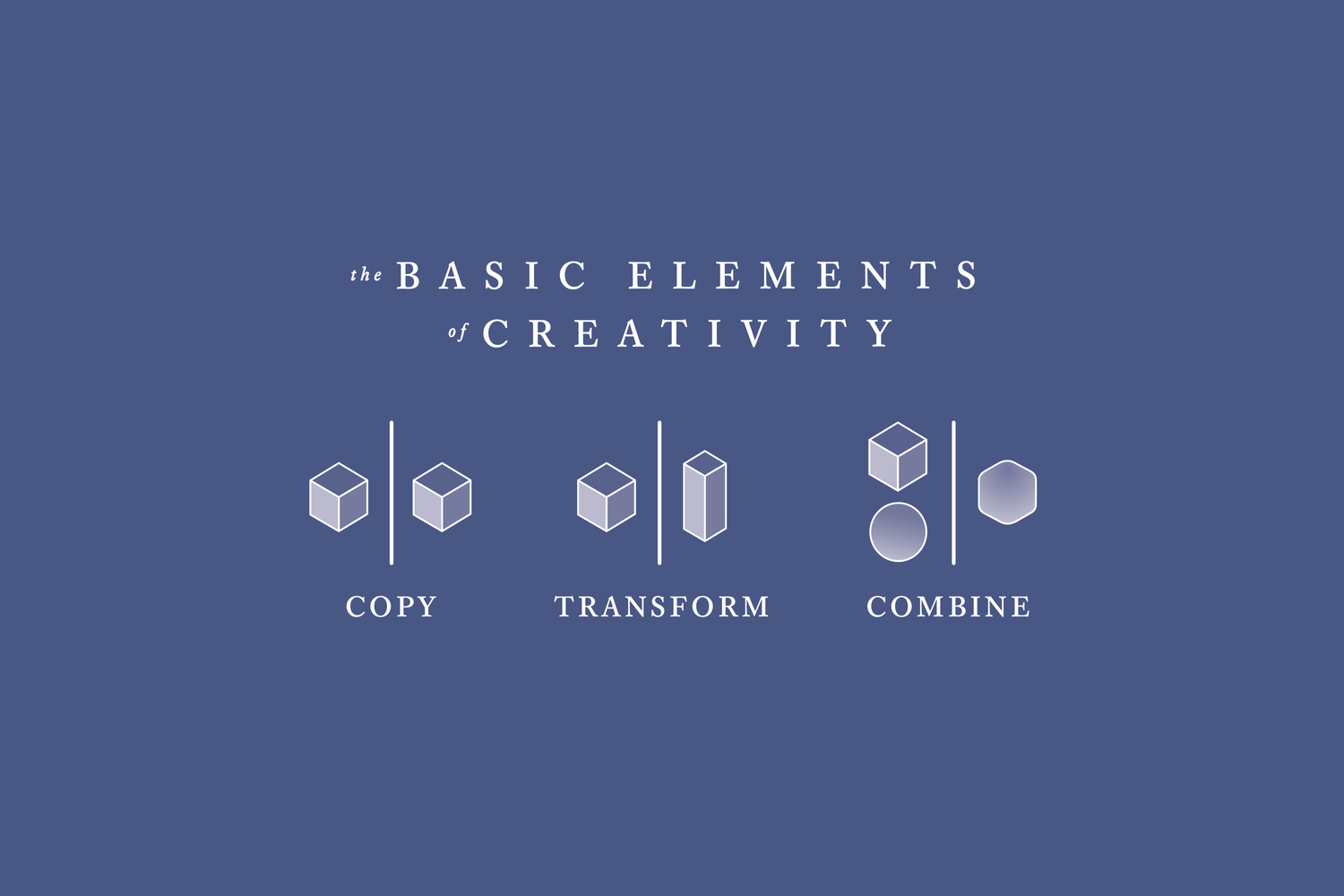

I find often in my annotations, the most recent one just above is such a one, where I start with a tiny kernel of an idea and then my brain begins warming up and I put down some additional thoughts. These can sometimes build and turn into multiple sentences or paragraphs, other times they sit and need further work. But either way, with some work they may turn into something altogether different than what the original author intended or discussed.

These are the things I want to keep, expand upon, and integrate into larger works or juxtapose with other broader ideas and themes in the things I am writing about.

Sadly, we're just not teaching students or writers these tidbits or habits anymore.

Sönke Ahrens mentions this idea in his book about Smart Notes. When one is asked to write an essay or a paper it is immensely difficult to have a perch on which to begin. But if one has been taking notes about their reading which is of direct interest to them and which can be highly personal, then it is incredibly easy to have a starting block against which to push to begin what can be either a short sprint or a terrific marathon.

This pattern can be seen by many bloggers who surf a bit of the web, read what others have written, and use those ideas and spaces as a place to write or create their own comments.

Certainly this can involve some work, but it's always nicer when the muses visit and the words begin to flow.

I've now written so much here in this annotation that this note here, is another example of this phenomenon.

With some hope, by moving this annotation into my commonplace book (or if you prefer the words notebook, blog, zettelkasten, digital garden, wiki, etc.) I will have it to reflect and expand upon later, but it'll also be a significant piece of text which I might move into a longer essay and edit a bit to make a piece of my own.

With luck, I may be able to remedy some of the modern note taking treatises and restore some of what we've lost from older traditions to reframe them in an more logical light for modern students.

I recall being lucky enough to work around teachers insisting I use note cards and references in my sixth grade classes, but it was never explained to me exactly what this exercise was meant to engender. It was as if they were providing the ingredients for a recipe, but had somehow managed to leave off the narrative about what to do with those ingredients, how things were supposed to be washed, handled, prepared, mixed, chopped, etc. I always felt that I was baking blind with no directions as to temperature or time. Fortunately my memory for reading on shorter time scales was better than my peers and it was only that which saved my dishes from ruin.

I've come to see note taking as beginning expanded conversations with the text on the page and the other texts in my notebooks. Annotations in the the margins slowly build to become something else of my own making.

We might compare this with the more recent movement of social annotation in the digital pedagogy space. This serves a related master, but seems a bit more tangent to it. The goal of social annotation seems to be to help engage students in their texts as a group. Reading for many of these students may be more foreign than it is to me and many other academics who make trade with it. Thus social annotation helps turn that reading into a conversation between peers and their text. By engaging with the text and each other, they get something more out of it than they might have if left to their own devices. The piece I feel is missing here is the modeling of the next several steps to the broader commonplacing tradition. Once a student has begun the path of allowing their ideas to have sex with the ideas they find on the page or with their colleagues, what do they do next? Are they being taught to revisit their notes and ideas? Sift them? Expand upon them. Place them in a storehouse of their best materials where they can later be used to write those longer essays, chapters, or books which may benefit them later?

How might we build these next pieces into these curricula of social annotation to continue building on these ideas and principles?

Is this Tess McGill's zettelkasten in the movie Working Girl?

Is this Tess McGill's zettelkasten in the movie Working Girl?