- Aug 2021

-

web.archive.org web.archive.org

-

In 2003, Ross's family gave his journals, papers, and correspondence to the British Library, London. Then, in March 2004, on the last day of the W. Ross Ashby Centenary Conference, they announced the intention to make his journal available on the Internet. Four years later, this website fulfilled that promise, making this previously unpublished work available on-line.

The journal consists of 7,189 numbered pages in 25 volumes, and over 1,600 index cards. To make it easy to browse purposefully through so many images, extensive cross-linking has been added that is based on the keywords in Ross's original keyword index.

This definitely sounds like a commonplace book. Also an example of one which has been digitized.

-

-

edwardbetts.com edwardbetts.com

-

Now, whenever I have a thought worth capturing, I write it on an index card in either marker pen or biro (depending on the length of the thought), and place in the relevant box. I use index cards for books, blogs, conversations I overhear at the club, memories, etc. They’re in my coat pocket when I fetch the kids from school. I leave them handy in the locker at the swimming pool (where I do much of my best thinking). And I run with them. Sound weird? Well, I’m in good company. Ryan Holiday[116], Anne Lamott[117], Robert Greene[118], Oliver Burkeman[119], Ronald Reagan, Vladimir Nabokov[120] and Ludwig Wittgenstein[121] all use (d) the humble index card to catalogue and organise their thoughts. If you’re serious about embarking on this digital journey, buy a hundred-pack of 127 x 76mm ruled index cards for less than a pound, rescue a shoebox from the attic and stick a few marker-penned notecards on their end to act as dividers. Write a “My Digital Box” label on the top of the shoebox, and you’re off.

apparently a quote from Reset: How to Restart Your Life and Get F.U. Money by David Sawyer FCIPR.

Notes about users of index card based commonplace books.

-

-

edwardbetts.com edwardbetts.comBooks1

-

Edward Betts is using his website as a commonplace book of sorts with a wide variety of topic headings based on his reading.

He also keeps a separate wiki: https://edwardbetts.com/wiki/

-

-

www.rossashby.info www.rossashby.info

-

http://www.rossashby.info/origins.html

This page looks like a zettelkasten card embedded into a commonplace book.He's cross linking ideas using page numbers. I wonder if he's also got headings as well?

-

-

groups.google.com groups.google.com

-

I am also interested in the work and method of Ross Ashby. His card index and notebooks have been put online by the British Commputer Society. I am fascinated by his law of requisite variety and how variety relates to complexity and its unfolding in general and in relation to design.

Sounds like Ross Ashby kept a commonplace book here.

Could be worth looking into: http://www.rossashby.info/ and digging further.

-

-

Local file Local file

-

In other words, the chapter titles of the Fundamenta botanicawere effectively titularheads which were transferable from one book to another and which served as labels for textualunits that could be moved through the space of the page in a manner that split books into chap-ters and chapters into books.

In much the way one might move around portions of ideas under heads in a commonplace book, Carl Linnaeus was moving around bigger ideas/chapters within books and moving from one book to another.

-

Like so manynaturalists of the Enlightenment, he was familiar with a wide variety of textual techniques, manyof which were direct descendants of the compositional and pedagogical tools used to harness themnemonic utility of words inscribed on the clean spaces of erasable surfaces such as librellos dememoria and chalk boards, or upon more permanent forms of print such as commonplace books(adversaria), cabinet labels, marginaliaand printed books.

Some interesting concepts to explore here.

-

when he laid out the early form of his classification method in a pamphletentitled Methodus(1736), he used heads to order the text.16

Carl Linnaeus' classification method in Systema Naturae, his famous nomenclature system, was informed by the traditional topical headings of commonplace books.

[16] The content of Methodus and the nature of the heads is addressed in S. Müller-Wille, ‘Introduction’, in C.Linnaeus, Musa Cliffortiana: Clifford’s Banana Plant, translated by S. Freer (Liechtenstein: A.R.G. Gantner VerlagK.G., 2007), 33

-

First, what were the economies of attention thatguided his commonplacing techniques? Second, what type of impact did his note-taking skillshave upon the way that he arranged information in texts?

The two questions addressed in this article.

-

The foregoing studies suggest two strands of commonplacing circa 1700. The first was thecollection of authoritative knowledge, usually in the form of quotations. The second was thecollection of personal or natural knowledge, with Francis Bacon’s lists, desiderata and apho-risms serving as early examples. While Moss has shown that the first strand was losing popular-ity by the 1680s, recent scholarship has shown that the second retained momentum through theeighteenth century,9especially in scientific dictionaries,10instructional cards,11catalogues,12

loose-leaf manuscripts,13syllabi14and, most especially, notebooks.15

There are two strands of commonplacing around 1700: one is the traditional collection of authoritative knowledge while the second was an emergent collection of more personal knowledge and exploration.

-

In recent decades there have been a number of stud-ies that have shown how humanist approaches to commonplacing not only evolved in tandemwith attempts to coherently arrange naturaliain studioli, wunderkammernand museums, butalso facilitated the conceptual development of natural history. Key works that led up to this rein-terpretation were Walter Ong’s work on Ramus, Frances Yates’s history of the art of memory,Tony Grafton’s defence of humanistic textual practices and, crucially, Paolo Rossi’s argumentthat Francis Bacon used topical logic to organize his lists and tables.7Once the topical box wasopened, a number of seminal studies on commonplacing natural knowledge followed. Keyentries in this canon are works written by Ann Blair, Ann Moss, Jonathan Spence and HowardHotson.8

Lots of references to add or read here.

-

Eddy, Mathew Daniel, Tools for Reordering: Commonplacing and the Space of Words in Linnaeus's Philosophia Botanica, Intellectual History Review, 20 (2010), 227-252

-

-

en.wiktionary.org en.wiktionary.org

-

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/adversaria

Note the use of adversaria also as a book of accounts. This is intriguing and gives a historical linguistic link to the idea of waste books being used in the commonplace tradition. When was this secondary use of adversaria used?

-

-

www.wired.com www.wired.com

-

This book consists of ideas, images, & quotations hastily jotted down for possible future use in weird fiction. Very few are actually developed plots—for the most part they are merely suggestions or random impressions designed to set the memory or imagination working. Their sources are various—dreams, things read, casual incidents, idle conceptions, & so on. —H. P. LovecraftPresented to R. H. Barlow, Esq., on May 7, 1934—in exchange for an admirably neat typed copy from his skilled hand.

Somewhat bizarre that Wired published this in this form without any sort of preamble or description.

-

-

www.amazon.com www.amazon.com

-

An edited and published volume of Ronald Reagan's commonplace book, which he kept on index cards.

-

-

www.usatoday.com www.usatoday.com

-

http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/washington/2011-05-08-reagan-notes-book-brinkley_n.htm

An article indicating that President Ronald Reagan kept a commonplace book throughout his life. He maintained it on index cards, often with as many as 10 entries per card. The article doesn't seem to indicate that there was any particular organization, index, or taxonomy involved.

It's now housed at the Reagan Presidential Library in Simi Valley, CA.

-

-

thoughtcatalog.com thoughtcatalog.com

-

Heyyy!!! I am so happy to see that I am not the only one following a similar system. I have lots of books marked in the same way and also with notes (by the way when taking notes use black ink - blue reflects in light and tired mind - ) and then my solution. After reading it all and taking notes, I categorized all my notes and distribute around my Excel file as attaching. Using this way I can add it to different categories and use it every where.

Look up Ken Wilber's system, which he apparently used for researching and writing his books.

-

Heyyy!!! I am so happy to see that I am not the only one following a similar system. I have lots of books marked in the same way and also with notes (by the way when taking notes use black ink - blue reflects in light and tired mind - ) and then my solution. After reading it all and taking notes, I categorized all my notes and distribute around my Excel file as attaching. Using this way I can add it to different categories and use it every where.

Example of person using Excel to keep a commonplace book.

-

-

ryanholiday.net ryanholiday.net

-

Just this year I made a gmail account, just for me to send myself creative ideas, interesting quotes, and write down moving experiences. I also send myself articles that I like and it’s nice to be able to write my thoughts or key words to go with it. Then the email can be organized into folders for the different themes. It’s a really easy way to bring it all with me and to never feel like I have to wait to record an idea.

An example of someone using a gmail account to create a commonplace book!

-

I have been thinking about putting this system into place for my own writing. I first came across it whilst reading ‘Lila’ by Robert Pirsig.

Apparently Robert Pirsig mentions the commonplace book idea in his book Lila.

-

-

It’s not totally dissimilar to the Dewey Decimal system and old library card catalogs.

Ryan Holiday notes the similarity of his method to that of the Dewey Decimal system and library card catalogs.

-

Ronald Reagan also kept a similar system that apparently very few people knew about until he died. In his system, he used 3×5 notecards and kept them in a photo binder by theme. These note cards–which were mostly filled with quotes–have actually been turned into a book edited by the historian Douglas Brinkley. These were not only responsible for many of his speeches as president, but before office Reagan delivered hundreds of talks as part of his role at General Electric. There are about 50 years of practical wisdom in these cards. Far more than anything I’ve assembled–whatever you think of the guy. I highly recommend at least looking at it.

Ronald Reagan kept a commonplace in the form of index cards which he kept in a photo binder and categorized according to theme. Douglas Brinkley edited them into the book The Notes: Ronald Reagan's Private Collection of Stories and Wisdom.

-

-It looks like the system is also very similar to Luhmann’s Zettelkasten. Though again, his discipline seems to exceed mine because I am a lot less ordered.

Ryan Holiday on 2014-04-01 mentioning Niklas Luhmann and his Zettelkasten and linking to another article.

Note he doesn't use the phrase commonplace book here, though the comments includes it.

-

-

www.gentlemanstationer.com www.gentlemanstationer.com

-

Zealous stationery guy writing generally about starting a commonplace book. He's more interested in the tactile portion of the process seemingly over the format and form.

-

-

www.gentlemanstationer.com www.gentlemanstationer.com

-

Unlike traditional journaling or commonplacing, my pocket notebooks don’t have any set format, and mostly amount to a collection of short lists, reminders, and random stream-of-consciousness jottings. These notebooks essentially serve the same purpose as scratch paper, only I have all of my random musings gathered together in one place as opposed to scattered around my desk on post-its and the backs of old grocery lists.

This is an example in the wild of someone using pocket notebooks as waste books. Though in this case they weren't actively moving pieces into a more permanent commonplace.

-

-

www.erasmusdarwin.org www.erasmusdarwin.org

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Commentarii

Relation to hypomnema

I'm curious how accurate these may have been and could they have contained falsehoods to support later re-imaginings of history? (cf. Relatio in the article Forging Communities by Jennifer Paxton).

-

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silva_rerum

Presumably these are the same sylvae mentioned by Earle Havens on page 10 of his book Commonplace Books (Yale, 2001).

Where do these fit into a historical commonplace tradition? From a timing and logical perspective they certainly could be a transplant from other parts of Europe in modified forms.

I'll note that some of the pattern is similar to printed bibles in the 1900's (and perhaps going back earlier) in the United States which held pre-printed pages for adding this sort of historical personal family data that would likely be handed down from generation to generation.

Compare and contrast this form to the idea of the Relatio chronicle in Jennifer Paxton's essay Forging Communities: Memory and Identity in Post-Conquest England.

-

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sammelband

Sammelband (/ˈzæməlbænt/ ZAM-əl-bant, plural Sammelbände /ˌzæməlˈbɛndə/ ZAM-əl-BEN-də or Sammelbands), or sometimes nonce-volume, is a book comprising a number of separately printed or manuscript works that are subsequently bound together.

Compare and contrast this publishing scheme with the idea of florilegium and commonplace books.

Did commonplace keepers ever sammelband their own personal volumes? And perhaps include more comprehensive indices?

What time periods did this pattern take place? How does this reflect on the idea of reorganizing early modern information management practices? Could these have bled over into the idea of the evolution of the Zettelkasten?

-

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hypomnemata

See definition of hypomnema.

May be useful to look at some of these literary works to compare/contrast them against commonplace books and their general use in early writings.

-

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hypomnema

Hypomnema (Greek. ὑπόμνημα, plural ὑπομνήματα, hypomnemata), also spelled hupomnema, is a Greek word with several translations into English including a reminder, a note, a public record, a commentary, an anecdotal record, a draft, a copy, and other variations on those terms.

Compare and contrast the idea of this with the concept of the commonplace book. There's also a tie in with the idea of memory, particularly for meditation.

There's also the idea here of keeping a note of something to be fixed or remedied and which needs follow up or reflection.

-

-

books.google.com books.google.com

-

Google Ngram Viewer for "commonplace book",florilegium,memex,"note taking"

-

-

Local file Local file

-

The issue of terminology is still problematic since some scholars insist that thegenre must be defined expansively in order to reflect accurately early modernpractice. Adam Smyth’s sixteen characteristics of commonplace book culture(II, A) are particularly useful in this regard

Adam Smyth compiled sixteen characteristics of commonplace book culture. This could be an interesting starting point for comparing and contrasting all the flavors of commonplace book relatives.

Adam Smyth, “Commonplace Book Culture: A List of Sixteen Traits,” in Women and Writing, c.1340–c.1650: The Domestication of Print Culture, ed. Anne Lawrence-Mathers and Phillipa Hardman (2010), pp.90–110

See also possibly: Smyth, Adam. “Printed Miscellanies: An Opening Survey,” in his “Profit and Delight”: Printed Miscellanies in England,1640–1682 (2004), pp.1–31.

-

Many of the snippets here talk about what was in individual commonplace books and how their contents indicated what was admired. What about the negative image of all the things which were excluded?

What things did people read which they didn't commonplace? What does that say about them? Their times? The way they thought?

Could their commonplacing be compared with their marginalia to show what rose to certain levels of interest and what didn't? Digging through the records to find and verify marginalia may be incredibly tedious in comparison with specifically kept things.

Some of my own fleeting notes, which I keep because it's easy, may show some interesting things about the way I think in comparison to those things upon which I expand, keep, and value more for my work and my worldview.

-

William Poole, “The Genres of Milton’sCommonplace Book,” inThe Oxford Handbook of Milton, ed. NicholasMcDowell and Nigel Smith (2009), pp.367–81, argues that since Milton’scommonplace book was an exercise in moral philosophy (the discipline towhich his headings of ethics, economics, and politics correspond), it wascompiled for action.

John Milton's commonplace book was an exercise in moral philosophy and it was compiled for action, not just a collection.

-

Yeo, “Notebooks as Memory Aids” (II, G), locates Locke’s views at a crucialjuncture in the status of memory, when commonplace books were seen assites for ordering information and not as prompts for recalling it.

Interesting datum along the timeline of commonplacebooks and memory. Worth logging and following.

Note the difference in the ideas of ordering information versus being able to recall it. How does this step in the evolution figure for the concept of the zettelkasten?

-

Hesperides, or The Muses’ Garden. Hao Tianhu, “Hesperides, or the Muses’Gardenand its Manuscript History,”Library10(2009),372–404, convincinglyunpacks the complicated history ofHesperides, a manuscript commonplacebook of thousands of passages of contemporary verse and prose extractsarranged alphabetically under headings which exists in two extant versions:Folger Shakespeare Library, MS V.b.93(compiled c.1654–66) and a secondversion based on the former that was prepared for print in1655–65but neverprinted, was cut up in the nineteenth century by James Orchard Halliwell-Phillipps, and now exists in three Folger manuscripts and seventy scrapbooksat the Shakespeare Centre Library in Statford-upon-Avon. Gunnar Sorelius,“An Unknown Shakespearian Commonplace Book,”Library28(1973),294–308, demonstrates that the source of the Shakespeare quotations cut andpasted into over sixty of Halliwell-Phillipps’ Shakespearean scrapbooks was amanuscript that also once contained the now-fragmentary Folger MSSV.a.75,79, and80, and argues that the manuscript is valuable for the light itsheds on seventeenth-century taste and on how a reader spontaneously editedShakespeare. Beal (III, E), vol.1, part2(1980), p.450, discovered thecompiler’s identity (John Evans), an entry in the Stationers’ Register for1655and an advertisement of1659indicating thatHesperideswas to be publishedby Humphrey Moseley (though it never was), and the existence of FolgerMS V.b.93.

This provides evidence and at least a date for the idea of cutting up books into scraps and then rearranging them to create a commonplace. Where does this fit into the continuum on the evolution of the zettelkasten idea?

How was this rearrangement physically done besides the cutting up of pieces? Were they pasted in? Clipped? other?

-

Francis Bacon. Angus Vine, “Commercial Commonplacing: FrancisBacon, the Waste-Book, and the Ledger,”EMS16(2011),197–218, analyzesBacon’s manuscript ‘Comentarius Solutus’ which includes comments onorganizing his twenty-eight notebooks, including several commonplacebooks, one of which is extant (British Library, MS Harley7017, fols83-129v); Bacon’s proposal of a method of note-taking that followed the mer-cantile practice of double-entry bookkeeping reconciled his desire to makethe commonplace book engage with not only words but also the world.

Francis Bacon used double-entry bookkeeping as par of his commonplace practice.

-

readers did not merely read for extractiblewisdom but also retained an interest in the work as a whole.

I'll note that I'm often reading for the inventio. It's not always what one can extract, but what interesting ideas that might be sparked anew.

-

RECENT STUDIES IN COMMONPLACE BOOKS

Burke provides a sort of miniature commonplace book about journal articles and books on commonplaces!

A great resource for an overview of some of the more recent studies (since year TK?) on commonplace book research.

-

Randall L.Anderson, “Metaphors of the Book as Garden in the English Renaissance,”YES33(2003),248–61, explains that seventeenth-century commentators sawmiscellanies as private, idiosyncratic collections and commonplace books asproduced with a readership in mind, for reference.

This would appear to be an interesting direct connection of the analogy of commonplaces to digital gardens.

-

Harold Love (III, G) distinguishes usefully between the common-place book and the miscellany

Look this up. I'd love to see a more delineated comparison of the difference between commonplace books and miscellanies.

-

KateEichhorn, “Archival Genres: Gathering Texts and Reading Spaces,”InvisibleCulture: An Electronic Journal for Visual Culture12(2008), correlates thecommonplace book and the blog as archival genres, transitional collectionsand spaces in which readers interact with texts and straddle public and privatespheres.

Interesting analogy of the genres of commonplacing and blogging.

What axes of genre and publication might one consider in creating such a comparison?

-

Peter Beal, “Notions in Garrison: The Seventeenth-Century Com-monplace Book,” inNew Ways of Looking at Old Texts: Papers of the Renais-sance English Text Society,1985–1991, ed. W. Speed Hill (1993), pp.131–47,

Look up this reference.

-

The term “commonplace book” typically refers to a collection ofhumanist-inspired extracts from classical writers arranged under topicheadings, but it is also sometimes used to describe an unstructured compi-lation of verse and prose passages. In this essay, the term refers to a book inwhich extracts were collected for reference, usually under topic headings.

Burke takes a much more limited definition of commonplace book than I generally do.

Tags

- John Milton

- philosophy

- exclusion

- references

- miscellany

- genres

- negative images

- scrapbooks

- inventio

- inclusion

- zettel

- memory

- scraps

- blogging

- commonplace books

- Adam Smyth

- open questions

- John Locke

- Francis Bacon

- worldview

- history

- definition

- zettelkasten

- digital gardens

- rhetoric

- active reading

Annotators

-

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Album_(Ancient_Rome)

Historical precursor of the idea of the modern album (photograph as well as musical), which also bears some resemblance to the commonplace book.

-

-

Local file Local file

-

" Havens' inclusive approach and argument for a broad definition of the commonplace book responds to previous scholarship whose scope has been restricted to documents that fit classical theories of the commonplace. In Havens' view, this exclusivity obscures much of the actual history and personal practices of compilers of commonplaces, particularly because it focuses on Renaissance humanist compilations that were made for print.

I take this more inclusive approach to note taking as well.

-

Reviewed Work(s): Commonplace Books: A History of Manuscripts and Printed Books from Antiquity to the Twentieth Century by Earle Havens

Review by: Daniel Knauss

Source: The Sixteenth Century Journal, Vol. 34, No. 2, Marriage in Early Modern Europe (Summer, 2003), pp. 610-611

Published by: Sixteenth Century Journal

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20061514

Tags

Annotators

-

-

-

Review: Printed Commonplace-Books and the Structure of Renaissance Thought by Ann Moss

Author(s): Terence Cave

Review by: Terence Cave

Source: Rhetorica: A Journal of the History of Rhetoric, Vol. 15, No. 3 (Summer 1997), pp. 337-340

Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the International Society for the History of Rhetoric

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/rh.1997.15.3.337

-

One might weU see a further example of this process in the incorporation into Alsted's Consiliarius académicas et schohsticus (1610) of a category of random, day-to-day observations and reading notes ("ephemerides" or "diaria").

Is this similar to the mixing of a daily journal page with note taking seen in systems like Roam Research and the way some use Obsidian?

-

Moss points out the implied analogy between the commonplace-book and "moveable type, capable of both setting a page of text in an apparentiy immutable form and of rearranging all the eléments of that page into other pattems for other meanings" (p. 252); with characteristie prudence, she mentions this analogy only when it finally becomes explicit in one of her later texts, Jean Oudart's Methode des orateurs oí 1668

The ideas of moveable type and moveable information can be an important idea in the evolution of commonplace books to zettelkasten and thence into digital forms of commonplaces.

-

At the heart of these is the shift from a manuscript culture to a print culture, which leads first to a rapid increase in the production and use of commonplace-books, and eventuaUy to a kind of implosión, where the wealth of materi-als available in print makes it virtuaUy impossible to devise a comprehen-sive compendium.

Was the decline of commonplaces in culture due to a sort of defeatist attitude about the ever-increasing amount of information?

Evidence of this can be found in the expressions of how impressive Niklas Luhmann's 90,000 index card zettelkasten is. For those without the value of keeping and using one, it can seem a lot of work, but to what end?

-

The importance of the Renaissance commonplace-book and the theory that underpins it has been acknowledged since the pioneering work of Robert Bolgar and others and reiterated by numerous Renaissance special-ists ever since.

Look into Robert Bolgar, this is the first I've seen his name in the space.

-

-

Local file Local file

-

After a long and influential career, commonplace books lost their influence in the late seventeenth century. Classical passages were relegated to the anti- quarian scholar; they no longer molded discourse and life. Men who sought confirmation in empirical evidence and scientific measurement had little use for commonplace books.

I believe that Earle Havens disputes the idea of the waning of the commonplace book after this.

I would draw issue with it as well. Perhaps it lost some ground in the classrooms of the youth, but Harvard was teaching the idea during Ralph Waldo Emerson's time during the 1800s. Then there's the rise of the Zettelkasten in Germany in the 1700s (and later officially in the 1900s).

Lichtenberg specifically mentions using his commonplace as a scientific tool for sharpening his ideas.

Can we find references to other commonplacers like Francis Bacon mentioning the use of them for science?

-

Moss shows how Protestant pedagogues such as Johann Sturm at Strasbourg used commonplace books in the schoolroo

What was the relationship, if any, between Johann Sturm, a Protestant pedagogue, and Petrus Ramus? Any link here in the offloading of memory into the commonplace book as a means of sidelining the ars memoria?

-

. Publishers quickly produced numerous printed commonplace books in order to satisfy the deman

I'll note that we've seen a similar trend here in publishers making copies of bullet journals in the past several years.

-

Review of Ann Moss. Printed Commonplace-Books and the Structuring of Renaissance Thought. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996. xiv + 345 pp. f, 80. ISBN: 0-1981- 5908-0

Author(s): Paul F. Grendler Review by: Paul F. Grendler Source: Renaissance Quarterly, Vol. 51, No. 3 (Autumn, 1998), pp. 1001-1002 Published by: University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Renaissance Society of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2901782

-

-

themorningnews.org themorningnews.org

-

Imagine a zettelkasten created by post?

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

He mentions Amazon wishlists that pile up and never get used. Similar to the way people pile up bookmarks and never use or revisit them.

One of the benefits of commonplace books (and tools like Obsidian, et al.) is that one is forced to re-see or re-discover these over time. This restumbling upon these things can be incredibly valuable.

-

- Jul 2021

-

drkimburns.com drkimburns.com

-

How do you remember what you read?

I too keep a commonplace book. First it was (and in part still is) on my personal website. Lately I've been using Hypothes.is to annotate digital documents and books, the data of which is piped into the clever tool (one of many) Obsidian.md, a (currently) private repository which helps me to crosslink my thoughts and further flesh them out.

I've recently found that Sönke Ahrens book How to Take Smart Notes: One Simple Technique to Boost Writing, Learning and Thinking – for Students, Academics and Nonfiction Book Writers is a good encapsulation of my ideas/methods in general, so I frequently recommend that to friends and students interested in the process.

In addition to my commonplace book, I also practice a wealth of mnemonic techniques including the method of loci/songlines and the phonetic system which helps me remember larger portions of the things I've read and more easily memorized. I've recently been teaching some of these methods to a small cohort of students.

syndication link: https://drkimburns.com/why-i-keep-a-commonplace-book/?unapproved=4&moderation-hash=d3f1c550516a44ba4dca4b06455f9265#comment-4

-

https://drkimburns.com/why-i-keep-a-commonplace-book/

A personal statement from a researcher that keeps one where she describes some of the how and why.

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

oldandgreat · 21hMe, and probably others, would be really interested to hear your book recommendations!2ReplyGive AwardShareReportSavelevel 4FluentFelicityOp · 20hThank you for sharing. I hope I am able to engage more intelligent readers like yourself in the future.I also agree with the other redditor. It's clear you have a much more comprehensive mental model of knowledge management than most of us who even regularly engage with this stuff.

I've probably read more and deeper about the space than most, but a lot of my knowledge here is practical in having worked on and used a commonplace for a while. I've generally figured out what does and doesn't work for me over the years. Having more than six months experience sure helps a lot. :) Book recommendations: Practical note taking and reading:

- Ahrens, Sönke. How to Take Smart Notes: One Simple Technique to Boost Writing, Learning and Thinking – for Students, Academics and Nonfiction Book Writers

- A recent sine qua non of note taking. Regardless of the form you're using, there's some very solid and practical advice here.

- Doren, Charles Van, and Mortimer J. Adler. How to Read a Book. Revised and Updated ed. edition. Touchstone, 2011.

- Adler compiled a massive encyclopedia using a version of a community zettelkasten. He's mired in the general tradition and this is a classic about how to think about reading.

- Photo: https://c7.alamy.com/comp/2FG8GNF/mortimer-j-adler-surrounded-by-his-great-ideas-photo-by-george-skaddingthe-life-picture-collection-via-getty-images-2FG8GNF.jpg History:

- Havens, Earle. Commonplace Books: A History of Manuscripts and Printed Books from Antiquity to the Twentieth Century. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library New Haven, CT, 2001.

- Great introduction to the definition and form over the last 2000 years. Nice timeline of history and some examples of use.

- Moss, Ann. Printed Commonplace-Books and the Structuring of Renaissance Thought. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198159087.001.0001.

- Comprehensive with some interesting speculation about their origin and evolution of commonplaces. Related books that are also relatively fun (for the space).

- Blair, Ann M. Too Much to Know. Yale University Press, 2011. https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300165395/too-much-know.

- Krajewski, Markus. Paper Machines: About Cards & Catalogs, 1548-1929. Translated by Peter Krapp. History and Foundations of Information Science. The MIT Press, 2011. https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/paper-machines.

- Ahrens, Sönke. How to Take Smart Notes: One Simple Technique to Boost Writing, Learning and Thinking – for Students, Academics and Nonfiction Book Writers

-

FluentFelicityOp · 12hBrilliant... I must ask you to share a little of your story. What brought you to have learned this much history and philosophy?

I've always had history and philosophy around me from a relatively young age. Some of this stems from a practice of mnemonics since I was eleven and a more targeted study of the history and philosophy of mnemonics over the past decade. Some of this overlaps areas like knowledge acquisition and commonplace books which I've delved into over the past 6 years. I have a personal website that serves to some extent as a digital commonplace book and I've begun studying and collecting examples of others who practice similar patterns (see: https://indieweb.org/commonplace_book and a selection of public posts at https://boffosocko.com/tag/commonplace-books/) in the blogosphere and wiki space. As a result of this I've been watching the digital gardens space and the ideas relating to Zettelkasten for the past several years as well. If you'd like to go down a similar rabbit hole I can recommend some good books.

-

-

uniweb.uottawa.ca uniweb.uottawa.caMembers2

-

Victoria E. Burke, Commonplace Genres, Or Women’s Interventions in Non-Traditional Literary Forms: Madame de Sablé, Aphra Behn, and the Maxim, World-making Renaissance Women: Rethinking Women's Place in Early Modern English Literature and Culture, Cambridge University Press Cambridge, 2022Editors: Pamela S. Hammons and Brandie R. SiegfriedEarly modern literatureSeventeenth-century women's writingFranceLiterary Genre

Another interesting one to pick up when it comes out.

-

Victoria E. Burke, Commonplacing, Making Miscellanies, and Interpreting Literature, The Oxford Handbook of Early Modern Women’s Writing in English, 1540-1680, Oxford University Press Oxford, 2022Editors: Danielle Clarke, Sarah C.E. Ross, and Elizabeth Scott-BaumannBook historyEarly modern literatureManuscript studiesSeventeenth-century women's writing

This looks like a fun read to track down.

-

-

digitalcollections.tcd.ie digitalcollections.tcd.ie

-

Papers of John Millington Synge: Literary Papers

John Millington Synge, the author of [[The Playboy of the Western World]] has several digitized commonplace books available at [[Trinity College Dublin]]'s library:

https://digitalcollections.tcd.ie/concern/subseries/tx31qh73c?locale=en

-

-

delong.typepad.com delong.typepad.com

-

To be informed is to know simply that something is the case. To be enlightened is to know, in addition, what it is all about: why it is the case, what its connections are with other facts, in what respects it is the same, in what respects it is different, and so forth.

The distinctions between being informed and enlightened.

Learning might be defined as the pathway from being informed as a preliminary base on the way to full enlightenment. Pedagogy is the teacher's plan for how to take this path.

How would these definitions and distinctions fit into Bloom's taxonomy?

Note that properly annotating and taking notes into a commonplace book can be a serious (necessary?) step one might take on the way towards enlightenment.

-

Mortimer]. Adler

Adler apparently kept a commonplace book in the form of a massive zettelkasten (and may have kept a more traditional commonplace book as well). I wonder if they detail any note taking details or advice here.

-

-

commonplaces.io commonplaces.io

-

This looks like a bookmarking service that is billing itself as a digital commonplace book. I'm not sure about the digital ownership aspect, but it does have a relatively pretty UI.

Looks like it works via a Chrome extension: https://chrome.google.com/webstore/detail/commonplaces-your-digital/ckiapimepnnpdnoehhmghgpmiondhbof

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

u/MushroomPuddle17 days agoGetting started with a commonplace notebook as someone who isn't creative? .t3_ojhwrb ._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; } Hello everyone!I've known about commonplace books for years and always feel a surge of inspiration when I see them but I'm really not creative. I don't know what I'd ever write in one? I don't ever really have any grand ideas or plans. I don't seem to have conversations or read things that necessarily inspire me. I just live a very regular life where nothing really sticks out to me as important. I've tried bullet journals before and had the same issue.Does anyone have any suggestions? I'd really appreciate it.

I'm not sure what you mean by your use of the word "creative". I'm worried that you've seen too many photos of decorative and frilly commonplace books on Instagram and Pinterest. I tend to call most of those "productivity porn" as their users spend hours decorating and not enough collecting and expanding their thoughts, which is really their primary use and value. Usually whatever time they think they're "saving" in having a cpb, they're wasting in decorating it. (Though if decorating is your thing, then have at it...) My commonplace is a (boring to others) location of mostly walls of text. It is chock full of creative ideas, thoughts, and questions though. If you're having trouble with a place to start, try creating a (free) Hypothes.is account and highlighting/annotating everything you read online. (Here's what mine looks like: https://hypothes.is/users/chrisaldrich, you'll notice that it could be considered a form of searchable digital commonplace book all by itself.) Then once a day/week/month, take the best of the quotes, ideas, highlights, and your notes, replies, questions and put them into your physical or digital commonplace. Build on them, cross link them, expand on them over time. Do some research to start answering any of the questions you came up with. By starting with annotating things you're personally interested in, you'll soon have a collection of things that become highly valuable and useful to you. After a few weeks you'll start seeing something and likely see a change in the way you're reading, writing, and even thinking.

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

I've used something like this in a textbook before while also using different colored pens to help differentiate a larger taxonomy. I found it to be better for a smaller custom cpb that only had a narrow section of topics. In my larger, multi-volume commonplace, I have a separate volume that serves as an index and uses a method similar to John Locke's, though larger in scope and shape. Sadly in this case, the index would be much too large (with too many entries) to make the high five method practicable.

-

-

www.highfivehq.com www.highfivehq.com

-

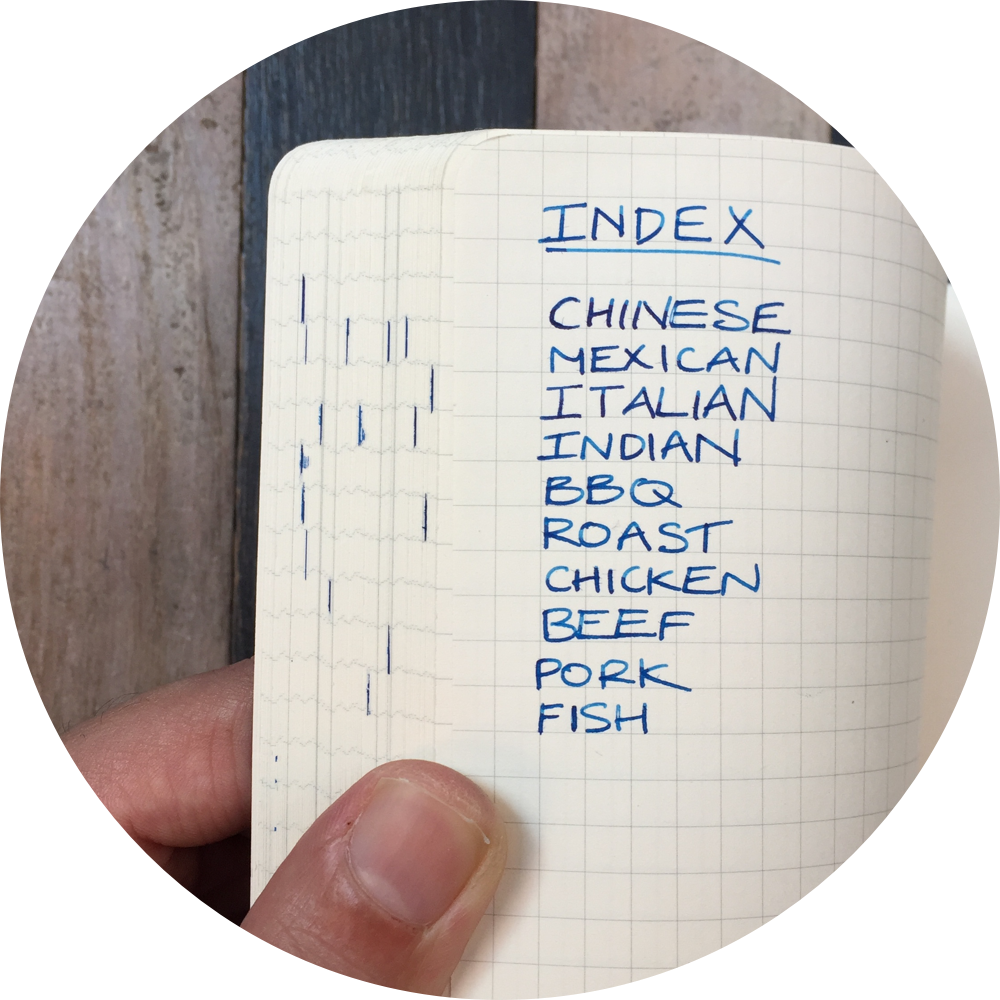

Highfive Notebook indexing method

A clever method for creating an index or tracking system in a bound notebook by creating an index and then marking the edge of the page for related pages.

Could also be used for tracking one's mood or other similar taxonomic items.

<small><cite class='h-cite via'>ᔥ <span class='p-author h-card'>u/mor-leidr </span> in Has anyone used this indexing system? Curious what you think : commonplacebook (<time class='dt-published'>07/30/2021 12:29:53</time>)</cite></small>

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

Of interest to many here, I and a few others have been maintaining a list of personal website-based online commonplace books, examples, tools, and related information for a few years. It can be found on the IndieWeb Community's wiki (aka a community-based digital commonplace book) at: https://indieweb.org/commonplace_book

It's got:

- links to online examples to view for potentially creating your own digital commonplace;

- lists of tools and resources for creating and maintaining a digital (and especially online) commonplace;

- lists of articles and related books which some (especially beginners) may find helpful;

- examples of written, historical and sometimes digitized and browsable online commonplaces;

- details about other commonplace "flavors" including: anthologies/florilegium, waste books/sudelbücher, wikis, second brains, and the increasingly popular Zettelkasten and digital gardens.

Syndicated copies: https://www.reddit.com/r/commonplacebook/comments/ourjnl/resources_for_personal_digital_online_commonplace/

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

u/thepoisonouspotato5 months agoWhat should I use for a Digital Commonplace book? .t3_lxgjgl ._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; } I never really kept my notes digitally, I have mostly used physical notebooks for journaling, bujoing and other stuffs, mostly decorating and spending a lot of time on it. But with my Uni and all the study pressure and a busy life I am often demotivated to get back on paper, cause I always find this voice inside me, "it should look good". So I'm planning to try a Digital Commonplace book, but since I never really did anything digitally I'm not sure if I can stick to it or not and I'm not up for investing in something I might leave in mid way. Anything you wanna suggest I can use as a beginner?

Did you pick something? How's it going? For ease of use and simplicity, I most often recommend and personally use the free Obsidian.md, so that I can own all the data and do other things with it easily if I choose. They've also got a very useful forum and a discord with sections on use for education/academia. If you're starting one for educational purposes, I highly recommend reading How to Take Smart Notes: One Simple Technique to Boost Writing, Learning and Thinking – for Students, Academics and Nonfiction Book Writers by Sönke Ahrens. It's written in the framing of a Zettelkasten, an index-card-based cousin of the commonplace, but the method is essentially equivalent to commonplacing and often seen in digital spaces lately. For other digital and online versions of commonplace software, I've been updating a list I (and others) maintain at https://indieweb.org/commonplace_book which has lots of options for either self-hosted solutions, commercial solutions as well as public/private options and examples.

-

-

browninterviews.org browninterviews.org

-

I like the idea of some of the research into education, pedagogy, and technology challenges here.

Given the incredibly common and oft-repeated misconception which is included in the article ("But Zettelkasten was a very personal practice of Nicholas Luhmann, its inventor."), can we please correct the record?

Niklas Luhmann positively DID NOT invent the concept of the Zettelkasten. It grew out of the commonplace book tradition in Western culture going back to Aristotle---if not earlier. In Germany it was practiced and morphed with the idea of the waste book or sudelbücher, which was popularized by Georg Christoph Lichtenberg or even re-arrangeable slips of paper used by countless others. From there it morphed again when index cards (whose invention has been attributed to Carl Linnaeus) were able to be mass manufactured in the early 1900s. A number of well-known users who predate Luhmann along with some general history and references can be found at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zettelkasten.

I suspect that most of the fallacy of Luhmann as the inventor stems from the majority of the early writing about Zettelkasten as a subject appears in German and hasn't been generally translated into English. What little is written about them in English has primarily focused on Luhmann and his output, so the presumption is made that he was the originator of the idea---a falsehood that has been repeated far and wide. This falsehood is also easier to believe because our culture is generally enamored with the mythology of the "lone genius" that managed Herculean feats of output. (We are also historically heavily prone to erase the work and efforts of research assistants, laboratory members, students, amanuenses, secretaries, friends, family, etc. which have traditionally helped writers and researchers in their output.)

Anyone glancing at the commonplace tradition will realize that similar voluminous outputs were to be easily found among their practitioners as well, especially after their re-popularization by Desiderius Erasmus, Rodolphus Agricola, and Philip Melanchthon in the emergence of humanism in the 1500s. The benefit of this is that there is now a much richer area of research to be done with respect to these tools and the educational enterprise. One need not search very far to discover that Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau's output could potentially be attributed to their commonplace books, which were subsequently published. It was a widely accepted enough technique that it was taught to them at Harvard University when they attended. Apparently we're now all attempting to reinvent the wheel because there's a German buzzword that is somehow linguistically hiding our collective intellectual heritage. Maybe we should put these notes into our digital Zettelkasten (née commonplace books) and let them distill a bit?

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.kristofferbalintona.me www.kristofferbalintona.me

-

I argue Zettelkasten’s essence is to repeatedly revisit, recall, and engage with that which you have learned, iterating upon the writing artifacts of that process—your crystallized thoughts—over time. Engaging with what you learn is the crux to a successful knowledge management system. The contribution of backlinks is too commonly conflated with the contribution of that routine. Backlinks are a complementary feature.

I think that this is the biggest part of the value proposition as well. Backlinks can be fun and useful, but it's all the other pieces that add the most value.

The long tradition of commonplace books in the Western intellectual tradition underlines this as well. The Zettelkasten is simply an iteration of the commonplace book instantiated into index card form.

-

-

forum.obsidian.md forum.obsidian.md

-

https://forum.obsidian.md/t/workflow-reading-ebook-epub-mobi-azw-etc-in-obsidian/17977

This is a clever hack for getting ebooks from Calibre to be readable within Obsidian, potentially for cutting/pasting and taking notes directly.

I think I still prefer my other methods, but this might be fun to play around with since I have so much stored in Calibre.

-

-

docdrop.org docdrop.org

-

Watched up to 2:33:00 https://youtu.be/wB89lJs5A3s?t=9181 with talk about research papers.

Some interesting tidbits and some workflow tips thus far. Not too jargony, but beginners may need to look at some of his other videos or work to see how to better set up pieces. Definitely very thorough so far.

He's got roughly the same framing for tags/links that I use, though I don't even get into the status pieces with emoji/tags as much as he does.

I'm not a fan of some of his reliance on iframes where data can (and will) disappear in the future. For Twitter, he does screencaptures of things which can be annoying and take up a lot of storage. Not sure why he isn't using twitter embed functionality which will do blockquotes of tweets and capture the actual text so that it's searchable.

Taking a short break from this and coming back to it later.

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

In the Western tradition, these memory traditions date back to ancient Greece and Rome and were broadly used until the late 1500s. Frances A. Yates outlines much of their use in The Art of Memory (Routledge, 1966). She also indicates that some of their decline in use stems from Protestant educational reformers like Peter Ramus who preferred outline and structural related methods. Some religious reformers didn't appreciate the visual mnemonic methods as they often encouraged gross, bloody, non-religious, and sexualized imagery.

Those interested in some of the more modern accounts of memory practice (as well as methods used by indigenous and oral cultures around the world) may profit from Lynne Kelly's recent text Memory Craft (Allen & Unwin, 2019).

Lots of note taking in the West was (and still is) done via commonplace book, an art that is reasonably well covered in Earle Havens' Commonplace Books: A History of Manuscripts and Printed Books from Antiquity to the Twentieth Century (Yale, 2001).

-

-

roam.garden roam.garden

-

There's apparently a product that will turn one's Roam Research notes into a digital garden.

Great to see a bridge for making these things easier for the masses, but I have to think that there's a better and cheaper way. Perhaps some addition competition in the space will help bring the price down.

-

-

bzawilski.medium.com bzawilski.medium.com

-

A lot of guru-esque figures have appeared in the personal knowledge management arena, but once you reach past some of the marketing bluster, there’s a lot to be gained by taking up a note-taking system to help organize your thoughts.

Sadly this article takes the magical thinking/guru idea to the extreme and misses the longer tradition of these ideas in Western thought.

-

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.orgHeadword1

-

The term 'lemma' comes from the practice in Greco-Roman antiquity of using the word to refer to the headwords of marginal glosses in scholia; for this reason, the Ancient Greek plural form is sometimes used, namely lemmata (Greek λῆμμα, pl. λήμματα).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Headword

No mention here of the use of headwords within the commonplace book tradition.

-

-

hackaday.com hackaday.com

-

https://hackaday.com/2019/06/18/before-computers-notched-card-databases/

Originally suggested by Alan Levine. Some interesting specific examples here, but I've been aware of the concept for a while.

-

-

thomasfoster.co thomasfoster.co

-

twitter.com twitter.com

-

who’s gonna let me create a digital garden / commonplace book on the blockchain

Registering that this was a question in the wild. Crazypants, but there it is.

What problem would this actually be solving though?!?

-

-

twitter.com twitter.com

-

Feature Idea: Chaos Monkey for PKM

This idea is a bit on the extreme side, but it does suggest that having a multi-card comparison view in a PKM system would be useful.

Drawing on Raymond Llull's combitorial memory system from the 12th century and a bit of Herman Ebbinghaus' spaced repetition (though this is also seen in earlier non-literate cultures), one could present two (or more) random atomic notes together as a way of juxtaposing disparate ideas from one's notes.

The spaced repetition of the cards would be helpful for one's long term memory of the ideas, but it could also have the secondary effect of nudging one to potentially find links or connections between the two ideas and help to spur creativity for the generation of new hybrid ideas or connection to other current ideas based on a person's changed context.

I've thought about this in the past (most likely while reading Frances Yates' Art of Memory), but don't think I've bothered to write it down (or it's hiding in untranscribed marginalia).

-

-

academic.logos.com academic.logos.com

-

I'm particularly interested here in the idea of interleaved books for additional marginalia. Thanks for the details!

An aspect that's missing from the overall discussion here is that of the commonplace book. Edwards' Miscellanies is a classic example of the Western note taking and idea collecting tradition of commonplace books.

While the name for his system is unique, his note taking method was assuredly not. The bigger idea goes back to ancient Greece and Rome with Aristotle and Cicero and continues up to the modern day.

From roughly 900-1300 theologians and preachers also had a sub-genre of this category called florilegia. In the Christian religious tradition Philip Melanchthon has one of the more influential works on the system: De locis communibus ratio (1539).

You might appreciate this article on some of the tradition: https://blog.cph.org/study/systematic-theology-and-apologetics/why-are-so-many-great-lutheran-books-called-commonplaces-or-loci

You'll find Edwards' and your indexing system bears a striking resemblance to that of philosopher John Locke, (yes that Locke!): https://publicdomainreview.org/collection/john-lockes-method-for-common-place-books-1685

-

The miscellanies, numbered and indexed, would often be noted in the margins of his Bible as well, especially if the note was an expansion of an exegetical point.

Interesting to see that Jonathan Edwards cross referenced his commonplace book to his bible as well.

-

As I studied Edwards’ writings and insights, I realized that I might be sitting at the feet of not only Edwards’ intellectual genius but his organizational genius, too.

For what I expect to be a coming description of Jonathan Edwards' commonplace book, I'm surprised that the page doesn't use the word or even florilegium.

Everhard here makes in one breath a common error I'm coming to notice. While it might be true that Edwards had some organizational genius, I think it's disingenuous to attribute his output to his intellectual genius. More and more I'm seeing that throughout history those who were thought of as intellectual geniuses really relied on the organization structures of their commonplace books (or similar devices). By writing, thinking, and producing in a commonplace tradition they were able to do far more, think more clearly, and accomplish more.

This can be linked with the idea also espoused in Robert Greene's Mastery which seems to have some of the similar flavor.

-

-

-

Best Bible Note-Taking System: Jonathan Edwards's Miscellanies

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fqq-4-LiFVs

Overview of Jonathan Edwards Miscellanies system along with a a few wide-margin bibles. Everhard apparently hasn't heard of the commonplace concept, though I do notice that someone mentions the zettelkasten system in the comments.

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

Most of this is material I've seen or heard in other forms in the past. It's relatively well reviewed and summarized here though, but it's incredibly dense to try to pull out, unpack and actually use if one were coming to it as a something new.

3 Productivity hacks

- Zen Meditation (Zen Mind, Beginners Mind by Shunryū Suzuki

- Research Process -- Annotations and notes, notecards

- Rigorous exercise routine -- plateau effect

The Zen meditation hack sounds much in the line of advice to often get away from what you're studing/researching and to let the ideas stew for a bit before coming back to them. It's the same principle as going for walks frequently heard from folks or being a flâneur. (cross reference Nassim Nicholas Taleb et al.) The other version of this that's similar are the diffuse modes of learning (compared with focused modes) described in learning theory. (Examples in work of Barbara Oakley and Terry Sejnowski in https://www.coursera.org/learn/learning-how-to-learn)

I've generally come to the idea that genius doesn't exist myself. Most of it distills down to use of tools like commonplace books.

Perhaps worth looking into some of the following to see what, if anything, is different than prior version of the commonplace book tradition:

The Ryan Holiday Notecard System @Intermittent Diversion - https://youtu.be/QoFZQOJ8aA0

Article On Notecard System [1] https://medium.com/thrive-global/the-notecard-system-the-key-for-remembering-organizing-and-using-everything-you-read-4f48a82371b1 [2] https://www.writingroutines.com/notecard-system-ryan-holiday/ [3] https://www.gallaudet.edu/tutorial-and-instructional-programs/english-center/the-process-and-type-of-writing/pre-writing-writing-and-revising/the-note-card-system/

-

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

-

Reminded by Connor of Mortimer Adler's Syntopicon. I'm pretty sure I've got it in my list of encyclopedias growing out of the commonplace book tradition, but... just in case.

If I recall it was compiled using index cards, thus also placing it in the zettelkasten tradition.

(via Almay)

(via Almay)

<script async src="https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js" charset="utf-8"></script>If you’re generalizing Zettelkasten to “All Non-Linear Knowledge Management Strategies” You should include Mortimer Adler and the Syntopicon, and John Locke’s guide to how to set up a commonplace book<br><br>This isn’t a game of calling “dibs”<br><br>it’s about 🧠👶shttps://t.co/sH3JO6d9Jq

— Conor White-Sullivan 𐃏🇸🇻 (@Conaw) July 8, 2021

-

-

-

This looks interesting upon a random Google search.

-

-

boffosocko.com boffosocko.com

-

and bullet journal for more modern take on commonplace books

Bullet Journals certainly are informed by the commonplace tradition, but are an incredibly specialized version of lists for productivity.

Perhaps there's more influence by Peter Ramus' outlining tradition here as well?

I've seen a student's written version of the idea of a Bullet Journal technique which came out of a study habits manual in the 1990's. It didn't quite have the simplicity of the modern BuJo idea or the annotations, but in substance it was the same idea. I'll have to dig up a reference for this.

-

This isn’t a game of calling “dibs”

It's definitely not a game of "dibs", but we're all fooling ourselves if we're not taking a look at the incredibly rich history of these ideas.

-

Your post says nothing at all to suggest Luhman didn’t “invent” “Zettelkasten” (no one says he was only one writing on scraps of paper), you list two names and no links

My post was more in reaction to the overly common suggestions and statements that Luhmann did invent it and the fact that he's almost always the only quoted user. The link was meant to give some additional context, not proof.

There are a number of direct predecessors including Hans Blumenberg and Georg Christoph Lichtenberg. For quick/easy reference here try:

- https://jhiblog.org/2019/04/17/ruminant-machines-a-twentieth-century-episode-in-the-material-history-of-ideas/

- https://muse.jhu.edu/article/715738

If you want some serious innovation, why not try famous biologist Carl Linnaeus for the invention of the index card? See: http://humanities.exeter.ac.uk/history/research/centres/medicalhistory/past/writing/

(Though even in this space, I suspect that others were already doing similar things.)

-

Not all the ancients are ancestors.

I'll definitely grant this and admit that there may be independent invention or re-discovery of ideas.

However, I'll also mention that it's far, far less likely that any of these people truly invented very much novel along the way, particularly since Western culture has been swimming in the proverbial waters of writing, rhetoric, and the commonplace book tradition for so long that we too often forget that we're actually swimming in water.

It's incredibly easy to reinvent the wheel when everything around you is made of circles, hubs, and axles.

-

Would love links to any descriptions of the systems used by Conrad Gessner (1516-1565) or Johann Jacob Moser (1701–1785)

I'm only halfway down the rabbit hole on some of these sources myself, a task made harder by my lack of facility with German. I am reasonably positive that the Gessner and Moser references are going to spring directly out of the commonplace book tradition, but include some of the innovation of having notes on slips of paper so that they're more easily re-arranged.

I'm also sitting on a huge trove of unpublished research which provides a lot more evidence and a trail of context which is missing from the short provocative statement I've made. I've added a few snippets to the Wikipedia page on Zettelkasten which outlines pieces for the curious.

I suspect soon enough I'll have a handful of journal articles and/or a book to cover some of the more modern history of notes and note taking that picks up where Earle Havens' Commonplace Books: A History of Manuscripts and Printed Books from Antiquity to the Twentieth Century (Yale, 2001) leaves off.

-

-

www.hps.cam.ac.uk www.hps.cam.ac.uk

-

Researcher working on the idea of Carl Linnaeus and the invention of the index card.

-

-

cathieleblanc.com cathieleblanc.com

-

Cathie is experimenting with Wikity for keeping reading notes.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

condensr.de condensr.de

-

<small><cite class='h-cite via'>ᔥ <span class='p-author h-card'>Matthias Melcher</span> in About | x28's new Blog (<time class='dt-published'>07/06/2021 11:09:19</time>)</cite></small>

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

x28newblog.wordpress.com x28newblog.wordpress.com

-

Which makes them similar to “commonplace”: reusable in many places. But this connotation has led to a pejorative flavor of the German translation “Gemeinplatz” which means platitude. That’s why I prefer to call them ‘evergreen’ notes, although I am not sure if I am using this differentiation correctly.

I've only run across the German "Gemeinplatz" a few times with this translation attached. Sad to think that this negative connotation has apparently taken hold. Even in English the word commonplace can have a somewhat negative connotation as well meaning "everyday, ordinary, unexceptional" when the point of commonplacing notes is specifically because they are surprising or extraordinary by definition.

Your phrasing of "evergreen notes" seems close enough. I've seen some who might call the shorter notes you're making either "seedlings" or "budding" notes. Some may wait for bigger expansions of their ideas into 500-2000 word essays before they consider them "evergreen" notes. (Compare: https://maggieappleton.com/garden-history and https://notes.andymatuschak.org/Evergreen_notes). Of course this does vary quite a bit from person to person in my experience, so your phrasing certainly fits.

I've not seen it crop up in the digital gardens or zettelkasten circles specifically but the word "evergreen" is used in the journalism space) to describe a fully formed article that can be re-used wholesale on a recurring basis. Usually they're related to recurring festivals, holidays, or cyclical stories like "How to cook the perfect Turkey" which might get recycled a week before Thanksgiving every year.

-

-

fedwiki.frankmcpherson.net fedwiki.frankmcpherson.net

-

Commonplace Book

Just ran into someone using FedWiki as a commonplace book via a random search.

-

-

www.jayeless.net www.jayeless.net

-

Finding these kinds of sites can be tough, especially if you’re looking for authentic 1990s sites and not retro callbacks, since Google seems to refuse to show you pages from over 10 years ago.

I think I've read this bit about Google forgetting from Tim Bray(?) before. Would be useful to have additional back up for it.

Not being able to rely on Google means that one's on personal repositories of data in their commonplace book becomes far more valuable in the search proposition. This means that Google search is more of a discovery mechanism rather than having the value of the sort of personalized search people may be looking for.

-

-

www.theatlantic.com www.theatlantic.com

-

Linnaeus may have drawn inspiration from playing cards. Until the mid-19th century, the backs of playing cards were left blank by manufacturers, offering “a practical writing surface,” where scholars scribbled notes, says Blair. Playing cards “were frequently used as lottery tickets, marriage and death announcements, notepads, or business cards,” explains Markus Krajewski, the author of Paper Machines: About Cards and Catalogs.

There was a Krajewski reference I couldn't figure out in the German piece on Zettelkasten that I read earlier today. Perhaps this is what was meant?

These playing cards might also have been used as an idea of a waste book as well, and then someone decided to skip the commonplace book as an intermediary?

-

Thomas Harrison, a 17th-century English inventor, devised the “ark of studies,” a small cabinet that allowed scholars to excerpt books and file their notes in a specific order. Readers would attach pieces of paper to metal hooks labeled by subject heading. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, the German polymath and coinventor of calculus (with Isaac Newton), relied on Harrison’s cumbersome contraption in at least some of his research.

Reference for this as well?

Is this the same piece of library furniture that I've also recently read of Leibniz using?

-

Many scholars, like the 17th-century chemist Robert Boyle, preferred to work on loose sheets of paper that could be collated, rearranged, and reshuffled, says Blair.

Reference for this? Perhaps in the Ann Blair text cited in this piece?

-

More than 1,000 of them, measuring five by three inches, are housed at London’s Linnean Society. Each contains notes about plants and material culled from books and other publications. While flimsier than heavy stock and cut by hand, they’re virtually indistinguishable from modern index cards.

Information culled from other sources indicates they come from the commonplace book tradition. The index card-like nature becomes the interesting innovation here.

-

-

www.sciencedaily.com www.sciencedaily.com

-

Linnaeus had to manage a conflict between the need to bring information into a fixed order for purposes of later retrieval, and the need to permanently integrate new information into that order, says Mueller-Wille. “His solution to this dilemma was to keep information on particular subjects on separate sheets, which could be complemented and reshuffled,” he says.

Carl Linnaeus created a method whereby he kept information on separate sheets of paper which could be reshuffled.

In a commonplace-centric culture, this would have been a fascinating innovation.

Did the cost of paper (velum) trigger part of the innovation to smaller pieces?

Did the de-linearization of data imposed by codices (and previously parchment) open up the way people wrote and thought? Being able to lay out and reorder pages made a more 3 dimensional world. Would have potentially made the world more network-like?

cross-reference McLuhan's idea about our tools shaping us.

-

-

www.heise.de www.heise.de

-

Dafür spricht das Credo des Literaten Walter Benjamin: Und heute schon ist das Buch, wie die aktuelle wissenschaftliche Produktionsweise lehrt, eine veraltete Vermittlung zwischen zwei verschiedenen Kartotheksystemen. Denn alles Wesentliche findet sich im Zettelkasten des Forschers, der's verfaßte, und der Gelehrte, der darin studiert, assimiliert es seiner eigenen Kartothek.

The credo of the writer Walter Benjamin speaks for this:

And today, as the current scientific method of production teaches, the book is an outdated mediation between two different card index systems. Because everything essential is to be found in the slip box of the researcher who wrote it, and the scholar who studies it assimilates it in his own card index.

Here's an early instantiation of thoughts being put down into data which can be copied from one card to the next as a means of creation.

A similar idea was held in the commonplace book tradition, in general, but this feels much more specific in the lead up to the idea of the Memex.

-

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716), der nicht nur angesehener Mathematiker und Philosoph war, sondern auch Bibliothekar der Herzog August Bibliothek in Wolfenbüttel, soll sich eigens einen Karteischrank als Büchermöbel nach eigenen Vorstellungen haben bauen lassen.

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716), who was not only a respected mathematician and philosopher, but also librarian at the Herzog August Library in Wolfenbüttel, is said to have had a filing cabinet built for him as book furniture according to his own ideas.

I'm curious to hear more about what this custom library furniture looked like? Could it have been the precursor to the modern-day filing cabinet?

I can picture something like the recent photo I saw of Bob Hope amidst his commonplace book.

-

-

-

snarkmarket.com snarkmarket.com

-

Revisiting this essay to review it in the framing of digital gardens.

In a "gardens and streams" version of this metaphor, the stream is flow and the garden is stock.

This also fits into a knowledge capture, growth, and innovation framing. The stream are small atomic ideas flowing by which may create new atomic ideas. These then need to be collected (in a garden) where they can be nurtured and grow into new things.

Clippings of these new growth can be placed back into the stream to move on to other gardeners. Clever gardeners will also occasionally browse through the gardens of others to see bigger picture versions of how their gardens might become.

Proper commonplacing is about both stock and flow. The unwritten rule is that one needs to link together ideas and expand them in places either within the commonplace or external to it: essays, papers, articles, books, or other larger structures which then become stock for others.

While some creators appear to be about all stock in the modern era, it's just not true. They're consuming streams (flow) from other (perhaps richer) sources (like articles, books, television rather than social media) and building up their own stock in more private (or at least not public) places. Then they release that article, book, film, television show which becomes content stream for others.

While we can choose to create public streams, but spending our time in other less information dense steams is less useful. Better is to keep a reasonably curated stream to see which other gardens to go visit.

Currently is the online media space we have structures like microblogs and blogs (and most social media in general) which are reasonably good at creating streams (flow) and blogs, static sites, and wikis which are good for creating gardens (stock).

What we're missing is a structure with the appropriate and attendant UI that can help us create both a garden and a stream simultaneously. It would be nice to have a wiki with a steam-like feed out for the smaller attendant ideas, but still allow the evolutionary building of bigger structures, which could also be placed into the stream at occasional times.

I can imagine something like a MediaWiki with UI for placing small note-like ideas into other streams like Twitter, but which supports Webmention so that ideas that come back from Twitter or other consumers of one's stream can be placed into one's garden. Perhaps in a Zettelkasten like way, one could collect atomic notes into their wiki and then transclude those ideas into larger paragraphs and essays within the same wiki on other pages which might then become articles, books, videos, audio, etc.

Obsidian, Roam Research do a somewhat reasonable job on the private side and have some facility for collecting data, but have no UI for sharing out into streams.

-

Where does this idea fit into the historical concept of the commonplace book?

-

-

www.gq.com www.gq.com

-

-

For the past thirty-some years, Rivers has been filing each and every joke she's written (at this point she's amassed over a million) in a library-esque card cabinet housed in her Upper East Side apartment. The jokes—most typed up on three-by-five cards—are meticulously arranged by subject, which Rivers admits is the hardest part of organizing: "Does this one go under ugly or does it go under dumb?"

Joan Rivers kept a Zettelkasten of jokes in her Upper East Side apartment. They spanned over thirty years and over a million items, most of them typed on 3"x5" index cards and carefully arranged by subject.

-

-

guides.loc.gov guides.loc.gov

-

The Joke File has been scanned into an internal database that is accessible on-site in both the Recorded Sound and Moving Image Research Centers.

Bob Hope's commonplace book of jokes has been scanned digitally and available at the United States Library of Congress.

-

-

www.loc.gov www.loc.gov

-

https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/bobhope/images/vcjokes1.jpg

Annie Leibovitz. Bob Hope in his joke vault. Photograph, July 17, 1995. Courtesy of Annie Leibovitz

https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/bobhope/images/vcjokes1.jpg

Annie Leibovitz. Bob Hope in his joke vault. Photograph, July 17, 1995. Courtesy of Annie LeibovitzBob Hope amidst his commonplace book of jokes.

-

The jokes included in the final script, as well as jokes not used, were categorized by subject matter and filed in cabinets in a fire- and theft-proof walk-in vault in an office next to his residence in North Hollywood, California. Bob Hope could then consult this “Joke File,” his personal cache of comedy, to create monologs for live appearances or television and radio programs. The complete Bob Hope Joke File—more than 85,000 pages—has been digitally scanned and indexed according to the categories used by Bob Hope for presentation in the Bob Hope Gallery of American Entertainment.

Bob Hope's joke file of over 85,000 pages represents a massive commonplace book of comedy.

-

-

-

A description of how George Carlin collected material for his comedy. No discussion of how he further worked on or refined it.

-

“It certainly makes me want to improve my own record-keeping and organization,” he says. “I think there’s a lot people can learn not just about building a comedy routine but about approaching mortality honestly. There’s a real sense of impermanence in all of what he saved.”

This links together the ideas of memory, commonplace books, and mortality.

This also underlines the idea that commonplaces could be very specific to their creators.

-

Over time, Carlin formalized that system: paper scraps with words or phrases would each receive a category, usually noted in a different color at the top of the paper, and then periodically those scraps would be gathered into plastic bags by category, and then those bags would go into file folders. Though he would later begin using a computer to keep track of those ideas, the basic principle of find-ability remained. “That’s how he built this collection of independent ideas that he was able to cross-reference and start to build larger routines from,” Heftel explains.

George Carlin's process of collecting and collating his material. His plastic bags by category were similar to the concept of waste books to quickly collect information (similar to the idea of fleeting notes). He later placed them into file folders (an iteration on the Zettelkasten using file folders of papers instead of index cards).

-

Seeing how his system worked is enough to inspire anyone not to let thoughts go to waste, notes Carlin estate archivist Logan Heftel. “A good idea,” Heftel says Carlin learned early, “is not of any use if you can’t find it.”

-

-

austinkleon.com austinkleon.com

-

-

In some sense, this very blog is a system for me to find out what I have: I take material from my notebooks and turn it into blog posts, and the posts become tags, which become book chapters, etc.

-

Like William Blake said, you either create your own system or get enslaved by another’s.

Interesting quote (direct attribution?) particularly within the context of commonplace books.

-