University of California, Berkeley — The Repatriation Project<br /> by Ash Ngu, Andrea Suozzo

- Mar 2023

-

projects.propublica.org projects.propublica.org

-

learningaloud.com learningaloud.com

-

How I would prompt ChatGPT to help me write an Introduction to Psychology Textbook<br /> by Mark Grabe

Contemplating writing an introductory psychology textbook (OER) using ChatGPT.

-

-

forum.zettelkasten.de forum.zettelkasten.de

-

we create (knowledge) tools to measure how good we are, and avoid just feeling good (Collector's Fallacy).

Collecting for collections' sake is a fools errand. Collecting to connect and create is where the magic happens.

-

-

twitter.com twitter.com

-

We create product not to show how good we are, but to measure how good we are.

<script async src="https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js" charset="utf-8"></script>We create product not to show how good we are, but to measure how good we are.

— Naval (@naval) February 19, 2023

-

-

zettelkasten.de zettelkasten.de

-

Little Machines in Your Zettelkasten<br /> by Sascha Fast

-

a Structure Note can make use of a TOC form, a normal table, a mind map, a flow diagram, a straight list, or even a picture.

Structure notes can take a variety of forms including lists, diagrams, mind maps, tables, and tables of contents.

-

-

twitter.com twitter.com

-

The beauty of FAST framework Overloaded with information → Filter Drowning in busywork → Automate Descending into chaos → Structure Doing things over and over → Templatize

<script async src="https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js" charset="utf-8"></script>The beauty of FAST framework<br><br>Overloaded with information → Filter<br><br>Drowning in busywork → Automate<br><br>Descending into chaos → Structure<br><br>Doing things over and over → Templatize pic.twitter.com/kn6Gi27DLG

— Andrew Altshuler (@1eo) February 4, 2023

-

-

notes.azlen.me notes.azlen.me

-

https://notes.azlen.me/g3tibyfv/

Inspired by Andy Matuschak's site

-

-

beepb00p.xyz beepb00p.xyz

-

https://beepb00p.xyz/

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

-

This research site has a digitized copy of Jonathan Edwards' commonplace book (aka Miscellanies): http://edwards.yale.edu/research/misc-index

-

-

niklas-luhmann-archiv.de niklas-luhmann-archiv.de

-

Tutorial: https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/bestand/zettelkasten/tutorial

Note search: https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/bestand/zettelkasten/suche

Table of contents for ZKI and ZKII: https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/bestand/zettelkasten/inhaltsuebersicht

-

-

www.rossashby.info www.rossashby.info

-

www.roland-barthes.org www.roland-barthes.org

-

https://www.roland-barthes.org/index.html

Roland Barthes research site maintained by Mathieu Messager.

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

Dans le fichier de Roland Barthes. Bibliothèque nationale de France, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eQX7jWqoq4o.

Watched 2023-03-03 at 11:55 AM

-

Mathieu Messager imagines a digital archive of Roland Barthes' Grand Fichier, but as of 2021-05-05 it has not yet been realized. He presented an imagined version of it in his presentation at the BnF.

-

A few times in his Grand Fichier, Barthes includes notebook paper from other sources which he's cut down to fit into his box or clippings of newspapers which he's taped to cards and included. ᔥ [00:32:00]

-

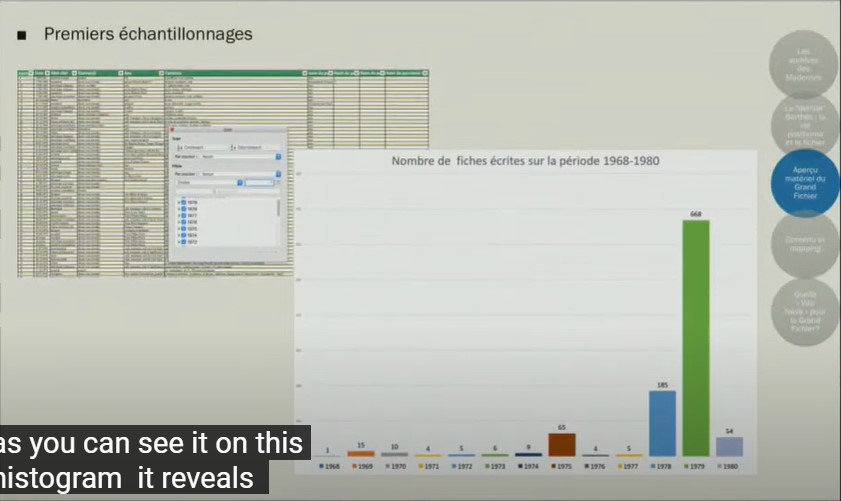

partir de 78 79 mais plutôt 79 et 81 donc dans les derniers dans les deux dernières années de sa vie l'avant veille de son accident l'a dit les prises de notes sont alors beaucoup moins espacées dans le temps et bar peut écrire jusqu'à une quinzaine de fiches par jour voire plus on voit ici sur ce diagramme l'année 1979 avec véritablement un bon mois à l'été 79 ou [00:29:35]

In 1978/79 Roland Barthes was making up to 15 cards per day. ᔥ

-

Histogram of Roland Barthes fiches between 1968 and 1980 from [29:28]

-

Since it seems more natural, I'm switching tags from "Roland Barthes' zettelkasten" to "Roland Barthes' fichier boîte". Future me will have to cross-correlate these.

-

avoir cela à l'esprit c'est vraiment du format a6 je le disais ce sont des fiches des feuilles a4 que bart devait plier et découper et à avoir un stock ainsi de feuilles pourra noter ce qui lui passait par la tête tout ce qu'ils avaient envie d'écrire jour après jour donc de petits formats elles se disent aussi en mode paysage n'est pas en mode portrait elles portent quasiment toute la date au recto comme [00:28:08]

Barthes used A4 sheets which he folded and cut by hand to make A6 sheets for his notes. Most sheets are in landscape orientation and dated by hand in the top right corner, though some appear in portrait orientation presumably as tabs with the month and year centered in the top.

-

de l'ensemble de cet objet le fond et sa cotation je passe très brièvement le grand fichier on l'a dit se compose ainsi on le voit 2083 fiches manuscrites qui sont datés donc entre 1968 et 1980 et conservés depuis 2010 depuis le don de michel salzedo on a dit au département des manuscrits de la bibliothèque nationale sur le site richelieu toutes ces fiches sont contenues dans deux boîtes distincts qui apparaissent ici à gauche qui porte la cotation de la bibliothèque nationale nouvelle acquisition française 28 600 34 51 et 4,52 dans ces deux boîtes [00:27:01] (via autogenerated subtitles in French)

The Grand Fichier de Roland Barthes is composed of two boxes with 1083 handwritten cards and dated between 1968 and 1980.

-

il existe donc un sous ensemble composite qui porte le nom de grand fichier il est composé de d'environ 1000 feuillets et 1083 pour être exact [00:19:13]

The grand fichier of Roland Barthes contains 1083 fiches. ᔥ

-

Roland Barthes has had published a number of works posthumously by way of his archives.

Were they all "finished" in his archive and then put out, or were they pieced together from outlines and notes? What state of preparation were they in?

-

There's something lovely about calling it le «Grand fichier» de Roland Barthes.

-

Michel Salzedo, Roland Barthes' brother, donated Barthes' papers to the BnF in 2010. [08:40]

Tags

- watch

- administrative note

- Roland Barthes

- Grand fichier

- Bibliothèque nationale de France

- Roland Barthes' zettelkasten

- references

- fleeting notes

- cards of equal size

- digitized note collections

- newspaper clippings

- 1979

- ars excerpendi

- Roland Barthes' fichier boîte

- 2010

- notes per day

- fichier boîte

- Fonds Roland Barthes

- histograms

- 2021-05-05

- Mathieu Messager

- posthumous publication

- 1978

- Michel Salzedo

- paper sizes

Annotators

URL

-

-

Local file Local file

-

Graeber, David. Pirate Enlightenment, or the Real Libertalia. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2023.

annotation target: url: urn:x-pdf:5a3fb6ca3c4ae2face96d0cb615518fe

Tags

Annotators

-

-

-

Blair, Ann M. Too Much to Know: Managing Scholarly Information before the Modern Age. Yale University Press, 2010, https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300165395/too-much-know.

ISBN: 978-0-300-11251-1 (cloth) Library of Congress Control Number: 2010024663

annotation target: url: urn:x-pdf:1a01bfa446187f0bb8bd5db6cc6ad53e

-

-

-

Paul, Annie Murphy. The Extended Mind: The Power of Thinking Outside the Brain. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2021, https://www.hmhbooks.com/shop/books/The-Extended-Mind/9780544947580.

annotation target: urn:x-pdf:37343666363464373933303538336161623732646237386463616662643365313266653032623035373331303031636338326237316361396637343432643431

-

-

learn-us-east-1-prod-fleet01-xythos.content.blackboardcdn.com learn-us-east-1-prod-fleet01-xythos.content.blackboardcdn.com

-

Graeber, David & Wengrow, David. The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity, McClelland & Stewart, 2021.

annotation target: url: urn:x-pdf:5cc55e090d83801cab6e2a2b429fa2e8

-

-

Local file Local file

-

Scheper, Scott. Antinet Zettelkasten: A Knowledge System That Will Turn You Into a Prolific Reader, Researcher and Writer. Greenlamp, LLC, 2022.

annotation target: url: urn:x-pdf:614d5b6d353f410da4a46e5eddde997e

-

-

-

Rank, Mark Robert, Lawrence M. Eppard, and Heather E. Bullock. Poorly Understood: What America Gets Wrong About Poverty. Oxford University Press, 2021.

Reading as part of Dan Allosso's Book Club

Mostly finished last week, though I managed to miss the last book club meeting for family reasons, but finished out the last few pages tonight.

annotation target: url: urn:x-pdf:c3701d1c083b974a888f7eaa4009f11f

-

-

Local file Local file

-

Piketty, Thomas. A Brief History of Equality. Translated by Steven Rendall. Harvard University Press, 2022. https://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674273559.

annotation target: url: urn:x-pdf:61f07d62a5664b0280bb35ee2d6a69e5

-

-

web.hypothes.is web.hypothes.is

-

Annotation and AI Starter Assignments<br /> by Jeremy Dean

- students as fact-checkers

- students as content experts

- students as editors

-

see also: https://web.hypothes.is/annotation-and-ai-starter-assignments/

-

A coming google project of interest here: https://hypothes.is/search?q=%22wordcraft%22

-

With respect to the predictive text portion of ChatGPT, a good non-technical (non-mathematical) description of a related mathematical model is described in chapter 3 of:

Pierce, John Robinson. An Introduction to Information Theory: Symbols, Signals and Noise. Second, Revised. Dover Books on Mathematics. 1961. Reprint, Mineola, N.Y: Dover Publications, Inc., 1980. https://www.amazon.com/Introduction-Information-Theory-Symbols-Mathematics/dp/0486240614.

-

-

-

After you've read a bit you may have some idea of some of the topics you'd like to cover and can begin creating an outline of what you'd like to express. Create a blank page and start the shape of the outline. As you proceed, you'll have an idea of a few specific notes that will fit under individual areas. What are those notes linked to? Perhaps add them as well if appropriate. As you outline you can add markup like

![[noteA]]to your outline which, in preview mode, will render or transclude the contents of that note and any others similarly formatted. Once you've done this with lots of notes you can copy/paste the contents into a draft which you can massage into finished form. Perhaps Obsidian's Canvas functionality might be helpful for you as well for mapping out the ideas/outline? It's at this point that many people realize how useful physical paper cards are for doing this process. The user interface and affordances in this last mile of output with respect to a digital tool is definitely a general drawback. This short video may be somewhat helpful for some of the process: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kxyy0THLfuI

-

-

www.amazon.com www.amazon.com

-

https://www.amazon.com/s?k=The+Cornell+Note-Taking+System+Walter+Pauk&ref=nb_sb_noss

Provides a page of pre-formated/printed notebooks for use with the Cornell note taking system.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

en.forum.saysomethingin.com en.forum.saysomethingin.com

-

Slow learner

reply to jo-king

https://en.forum.saysomethingin.com/t/slow-learner/38360/8

I don't do it as much as I did when I started out, but I would put the audio files into a podcatcher that allowed me to speed up or slow down the audio. The first time through I would slow the audio down to 75% of full speed so I didn't need to fiddle so much with the pause button (especially when I was listening while commuting or doing other household chores). Then I'd speed it up a bit each time until I was able to do 1.10 or 1.25x speed at which point the pauses weren't long enough to get a word in edgewise. At this point I move on to the next. Be careful here though as on some of the longer sentences at the ends of some lessons, if you play them too slowly, you'll forget what the beginning of the sentence was by the time they get to the end.

Based on a trick in my daughter's dual immersion Japanese class which used the word "wakanai" (Japanese for "I don't know"), I also formed the practice of saying "ddim gwybod" in place of words I couldn't immediately remember so that I could focus on the ones I did know instead of getting too tripped up on the ones I didn't. Eventually on repetition and revision they would slowly seep into my brain. Fortunately the kind and patient instructors on the tape never made fun of me or judged me for my mistakes and that made it much easier to eventually pick things up.

Sticking with it has become quite fun and it definitely gets easier with time. pob lwc!

-

-

sharegpt.com sharegpt.com

-

How does a zettelkasten differ from a card index?A zettelkasten is a type of note-taking system that originated in Germany and is typically used for knowledge management and creative writing. While a card index is a similar system, there are some key differences between the two.Structure: A zettelkasten is a hierarchical system of notes, where each note is linked to other notes through a system of cross-referencing. This means that each note can be linked to multiple other notes in a non-linear way. A card index, on the other hand, is typically organized in a linear fashion, with each card representing a discrete piece of information.Contextual linking: In a zettelkasten, notes are linked to other notes based on their context and relevance, rather than by a predetermined system of organization. This allows for more creative and flexible connections between ideas, and can help to generate new insights and connections. A card index, on the other hand, is typically organized based on a pre-defined system of categories or tags.Purpose: While both systems can be used for a variety of purposes, a zettelkasten is often used specifically for knowledge management, research, and creative writing. It is designed to help users capture and organize their ideas, and to facilitate the development of new insights and connections. A card index, on the other hand, can be used for a wider range of purposes, including contact management, recipe organization, and more.Overall, a zettelkasten and a card index are both useful note-taking systems, but they differ in terms of structure, contextual linking, and purpose. A zettelkasten is typically more flexible and creative, while a card index is more structured and organized.

https://sharegpt.com/c/0mrnsgg

Not a half bad answer...

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

help.openai.com help.openai.com

-

Will OpenAI claim copyright over what outputs I generate with the API? Written by Asher Ryan Updated over a week ago OpenAI will not claim copyright over content generated by the API for you or your end users. Please see our Terms of Use for additional details.

notice the specification of API here, what about non-API use?

-

-

sharegpt.com sharegpt.com

-

Can I use a card index for note taking?Yes, you can certainly use a card index for note-taking. Card indexes have been a popular method of note-taking for many years and can be very effective. Here are a few tips to get you started:Choose the right size of card index: Card indexes come in various sizes, so choose one that is comfortable for you to handle and store.Use cards of the same size: Using cards of the same size ensures that they will fit into your index box or file and that they will be easy to handle.Choose a system for organizing your cards: You can organize your cards alphabetically, by subject, by date, or any other system that works for you.Use one card per idea or topic: To keep your notes organized and easy to find, use one card per idea or topic.Keep your notes brief and to the point: Use brief notes that summarize the key points of your topic. This will make it easier to review your notes and find the information you need.Review your notes regularly: Review your notes regularly to keep the information fresh in your mind and to make sure you haven't missed anything important.Overall, a card index can be a very effective method of note-taking, as long as you develop a system that works for you and use it consistently.

Q: Can I use a card index for note taking?

Compare with: https://hypothes.is/a/HTqQPrksEe2XdQcSVvzXLQ

-

-

chat.openai.com chat.openai.comChatGPT2

-

Yes, you can definitely use a card index for note-taking. In fact, many people find card indexes to be a useful and convenient tool for organizing and storing notes. Here are some tips for using a card index for note-taking:Choose a system: Decide on a system for organizing your cards. You could organize them alphabetically, by topic, by date, or by any other method that works for you.Choose the size of cards: Choose the size of cards that works best for your needs. Common sizes include 3" x 5", 4" x 6", and 5" x 8".Use one card per idea: Write one idea or piece of information on each card. This will help keep your notes organized and easy to reference.Include keywords: Include keywords on each card to make it easier to find relevant information later.Use dividers: Use dividers to separate different topics or sections in your card index. This will help keep your notes organized and easy to navigate.Carry it with you: A card index is a portable tool, so you can take it with you wherever you go. This makes it easy to take notes on the go and to refer to your notes when you need them.Overall, a card index can be a useful and efficient tool for note-taking, especially if you prefer a physical, tangible way of organizing and storing information.

Q: Can I use a card index for note taking?

ChatGPT does a reasonable bit of advice on how one would use a card index for note taking.

-

ChatGPTThis is a free research preview.🔬Our goal is to get external feedback in order to improve our systems and make them safer.🚨While we have safeguards in place, the system may occasionally generate incorrect or misleading information and produce offensive or biased content. It is not intended to give advice.

-

-

-

<small><cite class='h-cite via'>ᔥ <span class='p-author h-card'>Hypothesis</span> in Liquid Margins 38: The rise of ChatGPT and how to work with and around it : Hypothesis (<time class='dt-published'>02/09/2023 16:11:54</time>)</cite></small>

-

-

platform.openai.com platform.openai.com

-

inst-fs-iad-prod.inscloudgate.net inst-fs-iad-prod.inscloudgate.netview1

-

Jackson, H. J. (2001). Marginalia: Readers writing in books. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Both of Jackson's books on marginalia are practically required reading: Marginalia: Readers Writing in Books and Romantic Readers: The Evidence of Marginalia

-

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

-

In short, in the absence of legal tender laws, the seller will not accept anything but money of certain value (good money), but the existence of legal tender laws will cause the buyer to offer only money with the lowest commodity value (bad money), as the creditor must accept such money at face value.

During the coronavirus pandemic, many vendors facing inflation began to pass along the 3% (or more) credit card processing fees to their customers. Previously many credit card companies would penalize vendors for doing this (and possibly cut them off). This fee was considered "the cost of doing business".

Some vendors prior to the pandemic would provide cash discounts on large orders because they could circumvent these fees.

Does this affect (harm) inflation? Is it a form of Gresham's law at play here? What effect does this have on credit card companies? Are they so integral to the system that it doesn't affect them, but instead the customers using their legal tender?

-

-

The old saying "a bad penny always turns up" is a colloquial recognition of Gresham's Law.

The colloquialism "a bad penny always turns up" is recognition of Gresham's law because the bad (cheap) pennies will be in higher circulation compared with purer or more valuable copper pennies which will have been hoarded or left circulation.

-

In economics, Gresham's law is a monetary principle stating that "bad money drives out good". For example, if there are two forms of commodity money in circulation, which are accepted by law as having similar face value, the more valuable commodity will gradually disappear from circulation.[1][2] The law was named in 1860 by economist Henry Dunning Macleod after Sir Thomas Gresham (1519–1579), an English financier during the Tudor dynasty. Gresham had urged Queen Elizabeth to restore confidence in then-debased English currency. The concept was thoroughly defined in medieval Europe by Nicolaus Copernicus and known centuries earlier in classical Antiquity, the Middle East and China.

Gresham's law is an economic monetary principle which states that "bad money drives out good."

It relates to commodity value, particularly in coinage, where cheaper base metals in coins will cause more expensive coinage to disappear from circulation.

-

-

www.theatlantic.com www.theatlantic.com

-

None of this is easy. In the words of Jill Lepore, one of our finest historians, “Writing history requires empathy, inquiry, and debate. It requires forswearing condescension, cant, and nostalgia. The past isn’t quaint. Much of it, in fact, is bleak.”

ostensibly in The Story of America: Essays on Origins

-

“Wisdom is the tears of experience,” the eminent sociologist Daniel Bell told my graduating class at Brandeis University.

-

Instructive quotations: Who doesn’t love a great quote? And quotations can work very well in a media environment that privileges brevity and catchiness. On the surface, the words of a past leader might seem explanatory for a topical news story, but dig a little deeper into the quote’s original setting, and the particularities—who said it, when, and for what purpose—might make the saying less apt.

Often instructive quotations aren't appropriate for the current situation because they have been stripped of their original context which doesn't apply to the new situation in which it is being used.

-

Nor does the cycles thesis have much to say about what social scientists call policy entrenchment—the way new policies outlast the coalition that created them.

Policy entrenchment is when policies outlast the people, movements, or coalitions that created those policies.

-

In their 1986 book, Thinking in Time, Ernest May and Richard Neustadt showed how bad analogies have led to poor foreign-policy decisions

Bad analogies can lead to poor decisions.

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

how did you teach yourself zettelkasten? .t3_11ay28d._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postBodyLink-VisitedLinkColor: #989898; }

reply to u/laystitcher at https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/11ay28d/how_did_you_teach_yourself_zettelkasten/

Roughly in order: - Sixth grade social studies class assignment that used a "traditional" index card-based note taking system. - Years of annotating books - Years of blogging - Havens, Earle. Commonplace Books: A History of Manuscripts and Printed Books from Antiquity to the Twentieth Century. New Haven, CT: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, 2001. - Locke, John, 1632-1704. A New Method of Making Common-Place-Books. 1685. Reprint, London, 1706. https://archive.org/details/gu_newmethodmaki00lock/mode/2up. - Erasmus, Desiderius. Literary and Educational Writings, 1 and 2. Edited by Craig R. Thompson. Vol. 23 & 24. Collected Works of Erasmus. Toronto, Buffalo, London: University of Toronto Press, 1978. https://utorontopress.com/9781487520731/collected-works-of-erasmus. - Kuehn, Manfred. Taking Note, A blog on the nature of note-taking. December 2007 - December 2018. https://web.archive.org/web/20181224085859/http://takingnotenow.blogspot.com/ - Ahrens, Sönke. How to Take Smart Notes: One Simple Technique to Boost Writing, Learning and Thinking – for Students, Academics and Nonfiction Book Writers. Create Space, 2017. - Sertillanges, Antonin Gilbert, and Mary Ryan. The Intellectual Life: Its Spirit, Conditions, Methods. First English Edition, Fifth printing. 1921. Reprint, Westminster, MD: The Newman Press, 1960. http://archive.org/details/a.d.sertillangestheintellectuallife. - Webb, Beatrice Potter. Appendix C of My Apprenticeship. First Edition. New York: Longmans, Green & Co., 1926. - Schmidt, Johannes F. K. “Niklas Luhmann’s Card Index: The Fabrication of Serendipity.” Sociologica 12, no. 1 (July 26, 2018): 53–60. https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.1971-8853/8350. - Hollier, Denis. “Notes (On the Index Card).” October 112, no. Spring (2005): 35–44. - Wilken, Rowan. “The Card Index as Creativity Machine.” Culture Machine 11 (2010): 7–30. - Blair, Ann M. Too Much to Know: Managing Scholarly Information before the Modern Age. Yale University Press, 2010. https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300165395/too-much-know. - Krajewski, Markus. Paper Machines: About Cards & Catalogs, 1548-1929. Translated by Peter Krapp. History and Foundations of Information Science. MIT Press, 2011. https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/paper-machines. - Goutor, Jacques. The Card-File System of Note-Taking. Approaching Ontario’s Past 3. Toronto: Ontario Historical Society, 1980. http://archive.org/details/cardfilesystemof0000gout.

And many, many others as I'm a student of intellectual history.... If you want to go spelunking on some of my public notes, perhaps this is an interesting place to start: https://hypothes.is/users/chrisaldrich?q=tag%3A%22note+taking%22 I also keep a reasonable public bibliography on this and related areas: https://www.zotero.org/groups/4676190/tools_for_thought

-

-

-

New book 'Myth America' examines misinformation in U.S. history<br /> https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HLAPfRqBHYs

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

revolutionpopuli.com revolutionpopuli.com

-

Flancian thought this was interesting.

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

In der aktuellen Folge „research_tv“ der Universität Bielefeld erklären Professor Dr. André Kieserling, Johannes Schmidt und Martin Löning, wie sie sich der so genannten „intellektuellen Autobiographie“ Luhmanns annähern.

Translation:

In the current episode "research_tv" of Bielefeld University, Professor Dr. André Kieserling, Johannes Schmidt and Martin Löning how they approach Luhmann's so-called “intellectual autobiography”.

!!

-

-

www.johndcook.com www.johndcook.com

-

Emacs on windows<br /> by John D. Cook

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

Analog Supplies

I should mention that the Stockroom Plus 4 x 6" cards I got a while back are great with even my juiciest fountain pens. They're some of the least expensive gridded cards I've been able to find and are a fraction of the cost of the Exacompta.

-

Analog Supplies .t3_11erqdi._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postBodyLink-VisitedLinkColor: #989898; }

- The Ultimate Guide to Zettelkasten Index Card Storage

- Index Card Accessories for Note Taking on the Go

- Be sure to check the comments for other options; I ended up binding my own using glue and chipboard which is both easy and inexpensive.

- For cost, custom made/printed slips may be the way to go for great paper if you're all-in. Many stationery/paper shops can help you custom design something.

- I've heard good things about Exacompa/Bristol index cards for fountain pens, but not tried them personally. They can tend toward the expensive side.

- Card bleachers and desk-based display options

- This playing card set is what I ultimately opted for

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

Definitely Exacompta. The color grid cards in 3x5 and 4x6 are fountain pen friendly and delightful to use.

u/abbienormal, u/Alan_Shutko, u/CynTut all recommend Exacompta cards for fountain pen friendly use.

4x6": - Goulet Pens - White Graph $9.00 - White lined $9.00 - White blank $9.00 - Pastel graph $13.50 - Flotsam and Fork Pastel graph $9.50 - Anderson Pens $13.50 (multi-color) - JetPens Pastel graph $14.50 - Amazon White(?) grid $19.96

- Kokuyo

- may be close in size but A or B style sizing

- Kokuyo

-

-

www.levenger.com www.levenger.com

-

https://www.levenger.com/products/nantucket-bamboo-compact-bleacher?variant=42489708773525

This sort of reminds me about the way Rick Nicita kept his to do list on index cards spread out all over his desk.

Perhaps he might have benefitted from an index card bleacher?

-

-

zettelkasten.de zettelkasten.de

-

Luhmanns intent was to create an organic growing system – not to implement Folgezettel.

I have a separate theory here...

-

A Zettelkasten is a system of notes that fit the criteria of being a system. Being alive vs. being a machine is a good metaphor to understand the difference. A Zettelkasten is alive, a conventional note taking system is a machine.

I'm not the only one to think of zettelkasten as "living"...

-

Luhmann’s Zettelkasten does not show the Zettelkasten Method

what is the meaning of "the" here (which is italicized for emphasis)?!?

-

My translation of Niklas Luhmann (1997): Die Gesellschaft der Gesellschaft, Frankfurt/M: Suhrkamp. S.11: “Bei meiner Aufnahme in die 1969 gegründete Fakultät für Soziologie der Universität Bielefeld fand ich mich konfrontiert mit der Aufforderung, Forschungsprojekte zu benennen, an denen ich arbeite. Mein Projekt lautete: Theorie der Gesellschaft; Laufzeit: 30 Jahre; Kosten: keine.”

As I began to work at the 1969 founded faculty of sociology of the University of Bielefeld, I was confronted with the request to name research projects I work on. My project was: a theory of society; Duration: 30 years; Costs: none.(1)

-

That entails that Luhmann had to close the system–environment border of the Zettelkasten in order to make it a system. The Zettelkasten had to be autopoietic, it reproduces only with its own elements. It can only connect to its own operations.

I don't think I buy any of this argument even on the surface level...

-

- Feb 2023

-

arstechnica.com arstechnica.com

-

www.hup.harvard.edu www.hup.harvard.edu

-

This Vast Southern Empire explores the international vision and strategic operations of these southerners at the commanding heights of American politics.

How does this book speak with respect to Immerwahr's How to Hide an Empire?

-

-

goodereader.com goodereader.com

-

Amazon removing titles from Kindle Unlimited due to ebook piracy issues<br /> by Sovan Mandal

Read at Tue 2023-02-28 6:50 AM

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

What screenwriting books recommend note cards for drafting/outlining? Do any go beyond the general outlining advice?

What is the overlap of this sort of writing practice with comedians who had a practice of writing jokes on index cards? (Ronald Reagan, Phyllis Diller, etc.?

-

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mwKjuBvNi40

Ben Rowland uses index cards to outline the plot of his screenplays. This is a common practice among screenwriters. Interestingly he only uses it for plot outlining and not for actual writing the way other writers like Vladimir Nabokov may have. Both Benjamin Rowland and Duston Lance Black use cards for outlining but not at the actual writing stage.

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

<small><cite class='h-cite via'>ᔥ <span class='p-author h-card'>Billy Oppenheimer</span> in The Notecard System: Capture, Organize, and Use Everything You Read, Watch, and Listen To (<time class='dt-published'>11/03/2022 16:53:44</time>)</cite></small>

Nothing stupendous here. Mostly notes on cards and then laid out to outline. Most of the writing sounds like it happens at the transfer stage rather than the card and outline stage.

This process seems more akin to that of Victor Margolin than Vladimir Nabokov.

-

NOW I SAY, "OKAY, THIS IS DONE." I READ IT. IT FEELS LIKE A MOVIE. AND I'M GONNA PUT IT IN THE BOX. AND I'M GONNA PUT IT IN THE BOX IN THIS ORDER, AND THIS IS THE ORDER THAT I'M GONNA WRITE IT IN IN MY FIRST DRAFT. OVER THE NEXT NUMBER OF WEEKS, I START WRITING. WHAT I'VE BEEN DOING, I'VE BEEN SEEING THE SCENES IN MY HEAD FOR SO LONG AT THIS POINT THAT IT'S ALMOST LIKE JUST REGURGITATION. LIKE, I'M JUST GETTING OUT. AND I CALL IT MY VOMIT DRAFT. #

Dustin Lance Black's "vomit draft" is similar to Mozart's peeing his music out like a cow. His method is also similar to Victor Margolin who's gone over the material several times by the time he's finally writing out his draft.

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5O8pBbcCWME

Harri Potter yn Cymraeg

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

duome.eu duome.eu

-

https://duome.eu/chrisaldrich/progress

Duolingo progress with words and grammar tabs

-

-

zettelkasten.de zettelkasten.de

-

Johnson's articles on DT were a great inspiration when I fiddled with the app. Surprise/serendipity is a moment he shares with the Zettelkasten Method -- but he focuses too much on finding new stuff in original sources (PDFs, web clippings), so you figured that out all right: his popular approach only makes you suffer from Collector's Fallacy more and more. Christian Tietze 2015-11-16 https://zettelkasten.de/posts/luedeckes-follow-up/#comment-2362116722

Christian Tietze credits Stephen Johnson for inspiration with respect to his DevonThink work and writing but accuses him of popularizing an approach which tends to draw people into the "collector's fallacy". Johnson's more traditional commonplace book approach seems to have worked incredibly well for him and allowed him to have a rather large output of books, articles, and blog posts over the years.

Tietze also suggests that the surprise/serendipity portion of the system works well for both the commonplace book and Luhmann-esque zettelkasten approaches.

-

-

zettelkasten.de zettelkasten.de

-

Fast, Sascha. “No, Luhmann Was Not About Folgezettel.” Topical Blog. Zettelkasten Method, October 31, 2015. https://zettelkasten.de/posts/luhmann-folgezettel-truth/.

-

I don’t think it is the best choice to realize Luhmann’s principles. Yet it is the best application adapting his techniques I know so far.

Sascha Fast appreciated Lüdecke's ZKN3 application as one of the best for adapting Luhmann's techniques to a digital space, but felt that it could have gone further in realizing Luhmann's principles.

Some of the tension in this debate is that between the affordances of analog (paper) versus digital information storage and tagging.

Paper lacks easy corpus text search while simultaneously requiring additional manual indexing to make up for it. Paper also doesn't have the discovery value of autocomplete. On the opposite end paper forces one to more regularly review physical associative trails through one's past work while digital allows one to skip over some of this review process.

-

Folgezettel

Do folgezettel in combination with an index help to prevent over-indexing behaviors? Or the scaling problem of categorization in a personal knowledge management space?

Where do subject headings within a zettelkasten dovetail with the index? Where do they help relieve the idea of heavy indexing or tagging? How are the neighborhoods of ideas involved in keeping a sense of closeness while still allowing density of ideas and information?

Having digital search views into small portions of neighborhoods like gxabbo suggested can be a fantastic affordance. see: https://hypothes.is/a/W2vqGLYxEe2qredYNyNu1A

For example, consider an anthropology student who intends to spend a lifetime in the subject and its many sub-areas. If they begin smartly tagging things with anthropology as they start, eventually the value of the category, any tags, or ideas within their index will eventually grow without bound to the point that the meaning or value as a search affordance within their zettelkasten (digital or analog) will be utterly useless. Let's say they fix part of the issue by sub-categorizing pieces into cultural anthropology, biological anthropology, linguistic anthropology, archaeology, etc. This problem is fine while they're in undergraduate or graduate school for a bit, but eventually as they specialize, these areas too will become overwhelming in terms of search and the search results. This problem can continue ad-infinitum for areas and sub areas. So how can one solve it?

Is a living and concatenating index the solution? The index can have anthropology with sub-areas listed with pointers to the beginnings of threads of thought in these areas which will eventually create neighborhoods of these related ideas.

The solution is far easier when the ideas are done top-down after-the-fact like in the Dewey Decimal System when the broad areas are preknown and pre-delineated. But in a Luhmann-esque zettelkasten, things grow from the bottom up and thus present different difficulties from a scaling up perspective.

How do we classify first, second, and third order effects which emerge out of the complexity of a zettelkasten? - Sparse indexing can be a useful long term affordance in the second or third order space. - Combinatorial creativity and ideas of serendipity emerge out of at least the third order. - Using ZK for writing is a second order affordance - Storage is a first order affordance - Memory is a first order affordance (related to storage) - Productivity is a second+ order (because solely spending the time to save and store ideas is a drag at the first order and doesn't show value until retrieval at a later date). - Poor organization can be non-affordance or deterrent which results in a scrap heap - lack of a reason why can be a non-affordance or deterrence as well - cross reference this list and continue on with other pieces and affordances

-

One piece of clutter was the concept of Folgezettel.

Sascha Fast felt in 2015 that the idea of Folgezettel within a zettelkasten was unnecessary "clutter".

Did he later change his mind after further discussion?

check this for further arguments: https://hypothes.is/a/xzuclLbBEe2Ov4viA3XOkQ

-

Update 2020-04-15: The topic re-emerged after a couple of years. There is quite some discussions in the forum. For example: Here, here and here. See this new post from 2020 for an expansion on that topic.

For the folgezettel debate check the following through 2020-04-15: - https://forum.zettelkasten.de/discussion/928/hierarchical-branched-note-taking-and-the-archive-app-is-topography-important - https://forum.zettelkasten.de/discussion/978/is-there-a-benefit-to-luhmann-ids-vs-date-time-ids - https://forum.zettelkasten.de/discussion/976/the-case-for-a-digital-folgezettel - https://zettelkasten.de/posts/understanding-hierarchy-translating-folgezettel/

-

I got rid of most of the features after I realized that they are redundant or a just plain harmful when they slowed me down.

Many long time practitioners of note taking methods, particularly in the present environment enamored with shiny object syndrome, will advise to keep one's system as simple as possible. Sascha Fast has specifically said, "I got rid of most of the features after I realized that they are redundant or a (sic) just plain harmful when they slowed me down."

-

During my journey of developing the Zettelkasten Method,

Seems like he's saying he developed the Zettelkasten Method... perhaps his version of the method based on Luhmann's? Commodifying the version "created" by Luhmann?

Credit here for native German speaker writing in English....

-

Principles are higher than techniques. Principles produce techniques in an instant. —Ido Portal

source?

Tags

- note taking affordances

- zettelkasten method

- zettelkasten origin myth

- neighborhoods

- folgezettel debate

- lost in translation

- quotes

- references

- complexity

- folgezettel

- examples

- topology of zettelkasten

- open questions

- planning

- read

- principles

- ZKN3

- shiny object syndrome

- zettelkasten

- Sascha Fast

- Ido Portal

- emergence

- scaling problem of categorization

- simplifications

- K.I.S.S.

- over-indexing

- Daniel Lüdecke

- gxabbo

- strategy

Annotators

URL

-

-

github.com github.com

-

ditchthattextbook.com ditchthattextbook.comHome1

-

notes.nicolevanderhoeven.com notes.nicolevanderhoeven.com

-

tantek.com tantek.com

-

-

www.propublica.org www.propublica.org

-

How to Report on the Repatriation of Native American Remains at Museums and Universities Near You<br /> by Ash Ngu, ProPublica

-

-

projects.propublica.org projects.propublica.org

-

Does Your Local Museum or University Still Have Native American Remains?<br /> by Ash Ngu, Andrea Suozzo (ProPublica)

-

-

www.bl.uk www.bl.uk

-

p143 contains details for calculation of gravity

-

1478-1518, Notebook of Leonardo da Vinci (''The Codex Arundel''). A collection of papers written in Italian by Leonardo da Vinci (b. 1452, d. 1519), in his characteristic left-handed mirror-writing (reading from right to left), including diagrams, drawings and brief texts, covering a broad range of topics in science and art, as well as personal notes. The core of the notebook is a collection of materials that Leonardo describes as ''a collection without order, drawn from many papers, which I have copied here, hoping to arrange them later each in its place according to the subjects of which they treat'' (f. 1r), a collection he began in the house of Piero di Braccio Martelli in Florence, in 1508. To this notebook has subsequently been added a number of other loose papers containing writing and diagrams produced by Leonardo throughout his career. Decoration: Numerous diagrams.

-

-

news.artnet.com news.artnet.com

-

Marginalia Uncovered in Leonardo's Famous Codex Arundel Suggests the Renaissance Polymath Theorized Gravity Before Galileo by Jo Lawson-Tancred, February 20, 2023, Artnet News

cc: @remikalir

-

-

www.nytimes.com www.nytimes.com

-

Despite the crudeness of his experimental setup 500 years ago, da Vinci, Dr. Gharib said, was able to calculate the gravitational constant to an accuracy within 10 percent of the modern value.

Nearly a hundred years before Galileo and two hundred years before Newton, in a series of diagrams and notes in the Codex Arundel, Da Viinci was able to calculate the gravitational constant to an accuracy within 10 percent of the accepted value.

-

The Codex Arundel, named after a British collector, the Earl of Arundel, who acquired it early in the 17th century. Da Vinci composed the collection of hundreds of papers between 1478 and 1518 — that is, between the ages of 26 and 66 — the year before his death. The papers now reside in the British Library. The collection features his famous mirror-writing as well as diagrams, drawings and texts covering a range of topics in art and science.

Da Vinci composed a collection of hundreds of papers from 1478 and 1518 which are now bound in the Codex Arundel, named for the Earl of Arundel who acquired it in the 17th century.

-

-

www.ebay.com www.ebay.com

-

VINTAGE quartersawn oak wood 2 drawer library card file catalog Cabinet 13x13x5

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.comYouTube5

-

Stop Procrastinating With Note-Taking Apps Like Obsidian, Roam, Logseq https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=baKCC2uTbRc by Sam Matla

sophisticated procrastination - tweaking one's system(s) or workflow with the anticipation it will help them in the long run when it is generally almost always make-work which helps them feel smart and/or productive. Having measurable results which can be used against specific goals will help weed this problem out.

-

Example of someone who says most of their best flashes of thought or creativity come when they're out walking or doing something else #

-

optimization-procrastination trap is related to shiny object syndrome - the idea of tweaking one's system constantly

perfect tool trap - guess what? there isn't one

-

"Personal knowledge management is an aid to your work, not the work itself." —Sam Matla #

This is entirely dependent on what and how you're doing it. If you're actively reading and annotating, and placing it somewhere, then that is the work, just in small progressive steps.

He needs to be more specific about what he means by "personal knowledge management" as a definition of something.

-

Sam Matla talks about the collector's fallacy in a negative light, and for many/most, he might be right. But for some, collecting examples and evidence of particular things is crucially important. The key is to have some idea of what you're collecting and why.

Historians collecting small facts over time may seem this way, but out of their collection can emerge patterns which otherwise would never have been seen.

cf: Keith Thomas article

concrete examples of this to show the opposite?

Relationship to the idea of AI coming up with black box solutions via their own method of diffuse thinking

Tags

- flâneur

- procrastination

- watch

- sophisticated procrastination

- optimization-procrastination trap

- perfect system fallacy

- diffuse thinking

- artificial intelligence

- tools are not the work

- aha moments

- examples

- card index for creativity

- productivity

- perfection is the enemy of progress

- eureka moments

- shiny object syndrome

- creativity

- productivity guru

- definitions

- collector's fallacy

- historical method

- note taking advice

- personal knowledge management

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.dalekeiger.net www.dalekeiger.net

-

G-L-O-R-EYE-EYE-EYE<br /> by Dale Keiger

-

-

forum.zettelkasten.de forum.zettelkasten.de

-

Not sure I completely follow the logic of the debate between Sascha and taurusnoises (Bob Doto) here. I'll have to look closer.

Perhaps mapping out the 1-1 distinctions between the digital and the analog here would be helpful. What structures would be needed to make them 1-1?

-

-

fz is less about the tree (though that is important) and more about the UX.

I do like the framing of folgezettel as a benefit with respect to user experience.

There is a lot of mention of the idea of trees within the note taking and zettelkasten space, but we really ought to be looking more closely at other living systems models like rhizomes and things which have a network-like structure.

-

-

-

Part 2: Search & Inspect. Denote as a Zettelkasten, 2023. https://share.tube/w/4ad929jjNYMLc6eRppVQmc.

His file naming convention and search operation in this is really fantastic:

20230226155400==51a3b--note-title__tag1_tag2.org

This allows one to search the file by date/time, signature, title or tags, by using the =, - or _ along with text.

Beyond this however, there's a fair amount of context to build to use this system including using regex search.

-

-

-

Part 1: What Do We Need? Denote as a Zettelkasten, 2023. https://share.tube/w/mu7fMr5RWMqetcZRXutSGF.

It starts and ends with Denote, but has an excellent overview of the folgezettel debate (or should one use Luhmann-esque identifiers within their digital zettelkasten system?)

Some of the tension within the folgezettel debate comes down to those who might prefer more refined evergreen (reusable) notes in many contexts, or those who have potentially shorter notes that fit within a train of thought (folgezettel) which helps to add some of the added context.

The difference is putting in additional up-front work to more heavily decontextualize excerpts and make them reusable in more contexts, which has an uncertain future payoff versus doing a bit less contextualization as the note will speak to it's neighbors as a means of providing some of this context. With respect to reusing a note in a written work, one is likely to remove their notes and their neighbors to provide this context when needed for writing.

(apparently I didn't save this note when I watched it prior to number 2, blech....)

-

-

strengejacke.wordpress.com strengejacke.wordpress.com

-

protesilaos.com protesilaos.com

-

ᔥ u/gxabbo in r/Zettelkasten - Video Series: Denote as a Zettelkasten (accessed:: 2023-02-26 02:52:52)

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

through research on the topic, i accidentally learned about the Zettelkasten industry.

—u/theinvertedform

It's an "industry" now! long live the zettelkasten capitalists!

antecedent: research on Walter Benjamin's Archive

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

Am I taking too long to finish notes? .t3_11bxjms._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postBodyLink-VisitedLinkColor: #989898; }

reply to u/m_t_rv_s__n at https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/11bxjms/am_i_taking_too_long_to_finish_notes/

Some of it depends on what you're reading for and what you're trying to get out of the reading. On a recent 26 page journal article, I spent several hours over a couple of days (months apart) reading and taking notes in a relatively thorough fashion. I spent another hour or so refining them further and filing them and another 15 minutes noting out references for follow up. It was in an area I'm generally very familiar with, so it wasn't difficult or dense, but has lots of material I specifically know I'll be using in the near future for some very specific writing. Because I know it's something of specific interest to me and several overlapping projects, I had a much deeper "conversation with the text" than I otherwise might have.

Because it was done digitally, you can see the actual highlights and annotations and even check the timestamps if you like (you'll have to click through individual notes to get these timestamps): https://hypothes.is/users/chrisaldrich?q=url%3Aurn%3Ax-pdf%3A6053dd751da0fa870cad9a71a28882ba Some of it is basic data I'll use for a variety of purposes on several already well-defined projects. A few are for more slowly developing projects further out on the horizon. It's relatively easy to see the 10 or 15 permanent notes that I'll pull out of this group of about 74 notes. Since writing them, I've already referenced two of the more fleeting notes/highlights by searching for related tags on other reading which look like they may actually develop further.

Had this been something less targeted to my specific area, say for a master's level course of general interest, I'd probably have spent far less time on it and likely not gone over about 15 or so notes. Sometimes for these, I'll just read the abstract and conclusions and scan the references. Reading lots of these in your area of interest gives you some idea of the space and types of questions you might be asking. As you hone in on a thesis, you'll begin asking more and more questions and delve more deeply into material, and if something you read in the past becomes more specific to your project then you'll likely go back to re-read it at a deeper level, but you'll still have your prior work at your fingertips as a potential guide.

Once you know what your particular thesis is going to be your reading becomes more dense and targeted. Some things you'll read several times and go through with fine-toothed combs while others you'll skim to get the gist/context and only excerpt small specific pieces which you need and then move on.

(If you need it, remember that you only need one or two good permanent notes per day to make some serious progress.)

-

-

docdrop.org docdrop.org

-

- ~ 90,000 notes

- 1,250 index entries

- 600 notes as manuscript outlines

- ~15,000 Literature notes

(10:35)

-

I have you two sheet boxes I gave up on that I'm using a to buy from a colleague of mine he's written a small program 00:46:58 based on lumen set accustomed but it's a one-man show I mean he's it's not an open-source project but it's the only one that really tries to emulate that system so 00:47:11 I'm using that at the moment

Ahrens had started out using his method in an analog process using shoe boxes, but in 2018 was using a small program based on Luhmann's process, but it was a one man show and wasn't an open source project.

(I'm pretty sure this is Daniel Lüdecke's ZKN3, but should double check.)

-

Ahrens, Sönke. “How to Take Smart Notes.” Presented at newcrafts: Professional Developer’s Conference at Paris, France, May 17, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nPOI4f7yCag.

annotations at https://docdrop.org/video/nPOI4f7yCag/

-

if you break it down it's just six notes a day 00:11:11 and that doesn't include Saturdays and Sundays

Ahrens' 6 notes per day calculation doesn't include Saturdays or Sundays

-

-

www.soenkeahrens.de www.soenkeahrens.de

-

My program of choice used to be ZKN3 by Daniel Lüdecke, which is free and developed explicitly to emulate the Zettelkasten, but it lacks the flexibility of newer apps. Alternatives of stand-alone Zettelkasten programs include Zettlr and The Archive.Nowadays, I use and value Roam Research, but would probably go with Obsidian if I had to start over today.

Sönke Ahrens used to use Daniel Lüdecke's ZKN3, but currently uses Roam Research, though he's said he might choose Obsidian if he were starting over again today.

-

-

www.zotero.org www.zotero.org

-

https://www.zotero.org/support/note_templates

Used this and the templates for setting up templates in Zotero to import notes from .pdf files into Zotero to migrate into Obsidian.

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

-

Posted byu/A_Dull_Significance6 hours agoWhat’s something you do with your Zettelkasten that you’re “not supposed to do”? .t3_11awtrx._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postBodyLink-VisitedLinkColor: #989898; } questionI think the title says it all.There are lots of ideas about things you should, or shouldn’t, do with you zettelkasten. What is something that works for you that you’re “not supposed to do”?For me, it’s the idea you shouldn’t keep quotes. I have a section (56/2) which is mainly a collection of different quotes on the topic of writing complexity and ease of comprehension. Some are for complexity, some against. Some place the burden on the writer, some on the reader, some mutual. I find it fruitful.What about you? What “rule” do you break?

Who made up this supposed rule against quotes! Are they not aware that quotes, particularly of sententiae, are some of the most excerpted and transmitted bits of knowledge in the entire Western canon? Without quotes, the entire tradition of note taking would probably not exist. Of course properly quoting is a sub-art in and of itself within rhetoric and the ars excerpendi.

A zettelkasten with no quotes— by definition— shouldn't carry the name.

-

level 2A_Dull_SignificanceOp · 2 hr. agoYes! When I run across a comment on a book I haven’t read yet but seems interesting I make a little card with the comment and book title2ReplyGive AwardShareReportSaveFollowlevel 2taurusnoises · 2 hr. agoObsidianSo, you keep the titles of books you want to read organized in folgezettel (you give them an alphanumeric ID?) among your ZK notes? That's really interesting!

I've done something like this when I think a particular reference(s) can answer a question related to a train of thought. But I keep cards of unread sources at the front of my sources section so that it's easier to pull it out frequently to prioritize and decide what I should be reading or working on next. These will then have links to the open questions I've noted, so that I can go back to those sections either as I'm reading/writing or to add those ideas into the appropriate folgezettel. These sorts of small amounts of work documented briefly can add up quickly over time. Source cards with indications of multiple open questions that might be answered is sometimes a good measure of desire to read, though other factors can also be at play.

That to-read pile of bibliographic source notes (a mini antilibrary) is akin to walking into a party and surveying a room. I may be aware of some of the people I haven't met yet and the conversations we might have, but if there are interesting questions I know I want to ask of specific ones or conversations I already know I want to have, it can be more productive to visit those first.

This sort of practice has been particularly helpful for times when I want to double check someone's sources or an original context, but don't have the time to do it immediately, don't want to break another extended train of thought, have to wait on materials, or may have to make a trip to consult physical materials that are singular or rare. For quick consultative reading, this can be a boon when I know I don't want or need to read an entire work, but skimming a chapter or a few pages for a close reading of a particular passage. I'll often keep a pile of these sorts of sources at hand so that I can make a short trip to a library, pick them up, find what I need and move on without having to recreate large portions of context to get the thing done because I've already laid most of the groundwork.

-

-

curtismchale.ca curtismchale.ca

-

Should You Read Antinet Zettelkasten by Scott P Scheper<br /> by Curtis McHale

Generally mirrors most of my opinion.

Odd that there haven't been many reviews of this...

-

What Scott is really engaged in is a religious argument.

amen

-

When an idea feels like too much work to write down, you just told yourself it wasn’t valuable enough.

-

They write a bunch of crap down that they wish they’d be able to do (secretly knowing they never will) and then their task manager gets overwhelming and they drop it because there is too much noise. This is why systems like Bullet Journal thrive in a digital world. When something is too hard to migrate to a new page or notebook, you just said it’s not worth doing and you let it go. Bullet Journal is a no-first system.

Bullet journaling works well in a noisy world because it forces people to confront what they're eventually not going to do anyway and gets them to drop it rather than leaving it on an ever-growing list.

Carrying forward to do lists manually encourages one to quit things that aren't going to get done.

-

There is no link to this book because you shouldn’t read it.

Scalding...

-

-

curtismchale.ca curtismchale.ca

-

PKM Weekly Feb 19 2023 – Issue 057 – Curtis McHale<br /> by Curtis McHale

-

Dendron is shutting down active development. (discord)

https://discord.com/channels/717965437182410783/737323300967022732/1072563304289030164

-

-

forums.zotero.org forums.zotero.org

-

Ctrl+Shift+Z

https://forums.zotero.org/discussion/71852/how-to-remove-or-edit-zotero-shortcut-in-chrome

Keyboard shortcut to add something to Zotero using Zotero connector browser extension.

Could potentially be changed at chrome://extensions/shortcuts

-

-

www.arthurperret.fr www.arthurperret.fr

-

Autobibliographie annotée (2018-2022) <br /> by Arthur Perret on 2023-02-20 (accessed:: 2023-02-24 11:30:20)

Perret looks back at several years of blogposts and comments on his growth over the intervening years. This sort of practice and providing indicators of best posts is an interesting means of digital gardening.

-

-

www.librariansmatter.com www.librariansmatter.com

-

Kathryn Greenhill in PhD notetaking workflow – PDF to Zotero to Zotfile to Dropbox to GoodNotes to Zotero to Scrivener. Blogjune 2019/7 at 2019-06-07 (accessed:: 2023-02-24 10:18:56)

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

Regina Martínez Ponciano aka u/NomadMimi in r/ObsidianMD - PhD workflow: Obsidian, Zettelkasten, Zotero, Pandoc, and more at 2021-03-15 (accessed:: 2023-02-24 10:10:11)

Broadly similar to my own workflow though I use Hypothes.is for fleeting notes rather than Zotero.

Original copy at: https://martinezponciano.es/2021/04/05/research-workflow-as-a-phd-student-in-the-humanities/

-

I started capturing everything directly in Obsidian but it has two major drawbacks. The first is that I will inevitably end up taking a lot of fleeting notes that I don't want to be included in the literature note. By taking the fleeting notes and highlights in Zotero, and then exporting a copy to Obsidian, I have the piece of mind that much raw material (that I might possibly need one day) is in Zotero, but that a more polished and reduced version is in my literature notes. The clutter stays in Zotero, in other words, while Obsidian is the home of the more processed notes.

Keeping one's fleeting notes separate from their permanent notes can be useful for managing the idea of clutter.

Luhmann generally did this by keeping things in different boxes. Modern academics may use different digital applications (Zotero/Obsidian, Hypothes.is/Zettlr, etc.as examples) for each as long as there is some reasonable dovetail between the two for data transfer when necessary.

-

If you want one final piece of (unsolicited) advice: if you bulk-import those Kindle highlights, please do not try to create literature Zettels out of everything. I did it and I DO NOT RECOMMEND. It was just too much work to rehash stuff that I had already (kind of) assimilated. Reserve that energy to write permanent notes (you probably know much more than you give yourself credit for) and just use the search function (or [^^]) to search for relevant quotes or notes. Only key and new papers/chapters you could (and should, I think) take literature notes on. Keep it fun!

Most veteran note takers will advise against importing old notes into a new digital space for the extra amount of administrative overhead and refactoring it can create.

Often old notes may be: - well assimilated into your memory already - poorly sourced or require lots of work and refactoring to use or reuse them - become a time suck trying to make them "perfect"

Better advice is potentially pull them into your system in a different spot so they're searchable and potentially linkable/usable as you need them. If this seems like excessive work, and it very well may be, then just pull in individual notes as you need or remember them.

With any luck the old notes are easily searchable/findable in whichever old system they happen to be in, so they're still accessible.

I'll note here the conflicting definitions of multiple storage in my tags to mean: - storing a single note under multiple subject headings or index terms - storing notes in various different (uncentralized locations), so having multiple different zettelkasten at home/office, storing some notes in social media locations, in various notebooks, etc. This means you have to search across multiple different interfaces to find the thing you're looking at.

I should create a new term to distinguish these two, but for now they're reasonably different within their own contexts that it's not a big problem unless one or the other scales.

-

I find it very tiring haha. As I said in another comment, processing a single chapter can take me a full day or two. However, I keep reminding myself that I would rather spend a day processing a chapter well, and have literature notes to serve me a lifetime (potentially, at least), rather than reading a chapter in two hours and not remember a single thing the next day. When I REALLY need a reminder of this, I just look at my "Backlog" folder which contains old "notes" that are now pretty much useless: I didn't use a reference manager consistently during my first two years of PhD so there are a lot of citations which are unreliable; I didn't really summarise texts, I only read them and highlighted; I didn't use the cloud for a long time, so I lost a lot of notes; and I didn't have Obsidian, so a lot of my notes are just contained within the context of the place I read them, rather than being connected. Seeing three years worth of useless materials, and knowing that I read a couple hundred of articles/chapters but I have nothing to show for it, that makes me more patient when writing my literature notes now. However I also find it very exciting that I can future-proof some of my notes. I feel like I'm working for my future self.

A partial answer to note taking why.

-

sometimes I’m afraid I’m more fighting the tools than doing research. Sometimes it seems to me there’s too much friction, and not the productive kind.

relation to Note taking problem and proposed solution?

This seems to be a common reality and/or fear.

-

I’m an imposter-perfectionist

—NomadMimi

Perfectionism is a good thing to be an imposter at.

-

I finished processing the 22 page chapter. It took me about 10 hours total to read, take notes, polish notes, and connect them to 39 permanent notes (6 new notes and 33 existing notes). Bear in mind, this is an extremely important reference for me, so it's by far one of the most-linked literature notes in my vault.

-

I knew you could do [[filename# to search for headings in a specific file, but I didn't realize you could do [[^^# to search all headings until I just tried it.

-

my Zettelkasten is named "House of Pomegranates", after my favorite Oscar Wilde short story collection.

Tags

- Zotero

- idea links

- future self

- card index as memory

- digital notes

- quotes

- fleeting notes

- note taking

- Zotfile

- tools for thought

- Obsidian for academia

- productivity

- read

- information processing

- time

- permanent notes

- naming

- importing notes

- search

- before and after

- note taking affordances

- note reuse

- multiple storage

- zettelkasten for academia

- note taking why

- fighting with tools

- friction

- imposter syndrome

- digital card index

- anecdotal evidence

- perfectionists

- subject headings

- examples

- note taking faq

- Pandoc

- Obsidian

- zettelkasten

- imposter perfectionist

- clutter

- workflows

- note taking advice

Annotators

URL

-

-

mailchi.mp mailchi.mp

-

INFORMA(C)TION No. 135: Plain Text <br /> by Jorge Arango at 2023-02-19 (accessed:: 2023-02-24 09:05:06)

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

blay.se blay.se

-

Vismann, Cornelia. Files: Law and Media Technology. Stanford University Press, 2008.

This looks intriguing...

autocomplete tells me I've seen her before....

update: it's a Rowan Wilken reference! https://hypothes.is/a/xwRnzr-REeyvvDd7YBbLVA

-

Living with a Zettelkasten | Blay <br /> by Magnus Eriksson at 2015-06-21 <br /> (accessed:: 2023-02-23 06:40:39)

a zettelkasten method one pager based generally on Luhmann's example and broadly drawn from material only on zettelkasten.de up to the date of writing in 2015.

Interesting to see the result of a single source without any influence from Ahrens, Eco, or any others from what I can tell. Perhaps some influence from Kuehn, but only from the overlap of zettelkasten.de and Kuehn's blog.

Note that it's not as breathless as many one page examples and doesn't focus on Luhmann's massive output, but it's still also broadly devoid of any other history or examples.

I would have hoped for more on the "living with" portion that was promised.

-

A sequence of Folgezetteln notes in the filenames of the Zettelns can from this perspective be considered a hardcoded outline and should be avoided, however convenient it seems.

And here he says it out loud... see https://hypothes.is/a/Gl5ferPsEe2Yf5P83a3wUg

-

But it is your writing that is the map, not the Zettelkasten, it can’t do that for you, you have to put in the work.

He's arguing here for even more work to make an outline for writing as if some of that work hasn't already been done. This seems very off to me.

The author would likely fall into the "folgezettel is not an outline" camp. I take a middle ground that it could be an outline or at least help to lower the activation threshold to making one.

-

You are presented with traces of your past thoughts, each Zettel bringing something back to life within you, lighting up some parts of your brain that start to remember those trains of thoughts the memory had sorted away.

traces of your past thoughts feels closely related to Vannevar Bush's associative trails

-

The collector’s fallacy should be channeled, not squashed. Cherish your inner “archive fever”[12] — it is your engine — but channel it to productivity. Use strategic procrastination.

The second reference to "archive fever" in almost as many weeks.

- Derrida, Jacques, and Eric Prenowitz. Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

-

Collecting does not transform us and always postpones learning and transformation to the future. Collecting creates debt that we promise to pay back in some future that never arrives.

There's some truth and falsity here...

-

Life in Zettelkasten is more like dance than a factory.

link to related: https://hypothes.is/a/whBvKrLnEe2OvPOgSd_4zg

-

A Zettelkasten becomes uninteresting when 1) It does not grow, 2) it grows only with isolated notes, 3) it never produces an output.

Factors that will cause one to lose interest in the maintenance of their card index...

-

In computer science, this is called “Separation of concerns” [1507211921].

Has the author accidentally included a zettelkasten identification number here?

-

The core of the system is a collection of shorter notes with links between them.

anecdotal definition/summary of zettelkasten.

I like the "shorter notes" idea here which would have arisen before the "atomic notes" or "evergreen notes" ideas.

-

implemented on index cards

Interesting to see a somewhat out of place link to Pile of Index Cards system here.

Given the 2015 date of the post this could be a part of the small distribution of the 2006 idea into the conversation a decade later.

-

The term Zettelkasten comes from Luhmann’s note-taking system.

At least they don't say he invented it...

Tags

- zettelkasten method

- outlines

- traces of past thoughts

- administrative debt

- media studies

- note lengths

- zettelkasten origin myth

- associative trails

- zettelkasten numbering

- folgezettel is not an outline

- quotes

- cognitive load

- zettelkasten death

- information management

- dance

- Pile of Index Cards

- writing process

- zettelkasten method one pager

- folgezettel

- associative memory

- read

- 2015

- Jacques Derrida

- archive fever

- Cornelia Vismann

- typo

- zettelkasten

- definitions

- files

- collector's fallacy

- learning

- factories

- Vannevar Bush

Annotators

URL

-

-

forum.zettelkasten.de forum.zettelkasten.de

-

Remember that life in a Zettelkasten is supposed to be fun. It is a joyful experience to work with it when it works back with you. Life in Zettelkasten is more like dance than a factory.

I've always disliked the idea of "work" involved in "making" notes and "processing" them. Framing zettelkasten and knowledge creation in terms of capitalism is a painful mistake.

the quote is from https://blay.se/2015-06-21-living-with-a-zettelkasten.html

-

-

www.amazon.com www.amazon.com

-

forum.zettelkasten.de forum.zettelkasten.de

-

reply https://forum.zettelkasten.de/discussion/comment/16622/#Comment_16622

Adler has an excellent primer on this subject that covers a lot of the basics in reasonable depth: - Adler, Mortimer J. “How to Mark a Book.” Saturday Review of Literature, July 6, 1940. (https://stevenson.ucsc.edu/academics/stevenson-college-core-courses/how-to-mark-a-book-1.pdf)

Marking books can be useful not only to the original reader, but future academics and historians studying material culture (eg: https://apps.lib.umich.edu/online-exhibits/exhibits/show/marks-in-books), and as @GeoEng51 indicates they might be shared by friends, family, romantic interests, or even perhaps all of the above (see: https://newcriterion.com/issues/2017/4/mrs-custers-tennyson).

For those interested in annotation marks and symbols (like @ctietze's "bolt" ↯) I outlined a few ideas this last month at: https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/10qw4l5/comment/j6vxn6a/?utm_source=reddit&utm_medium=web2x&context=3

-

-

newcriterion.com newcriterion.com

-

Mrs. Custer’s Tennyson April 2017<br /> by William Logan

-

-

spectator.org spectator.org

-

Reagan’s Note Card Treasures<br /> by John H. Fund <br /> at August 10, 2011, 12:00 AM<br /> (accessed:: 2023-02-23 12:25:06)

archived copy: https://web.archive.org/web/20151017020314/http://spectator.org/articles/37399/reagans-note-card-treasures

-

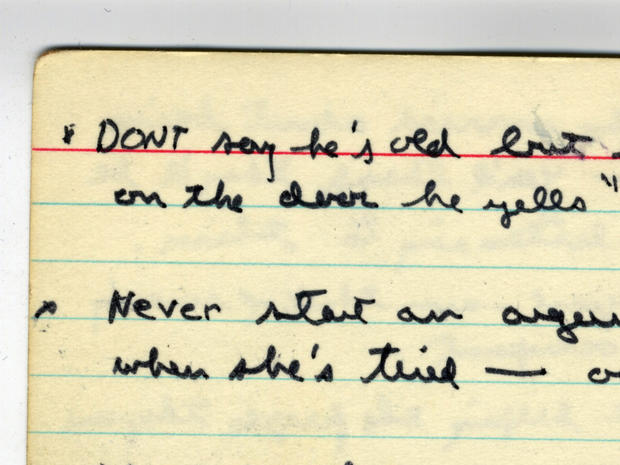

WHILE REAGAN was governor, I will never forget his taking time out of his schedule after a television taping to show me—a 15-year-old high school student—how he could instantly arrange his packs of anecdote-filled index cards into a speech tailor-made for almost any audience. I still use a variation of Reagan’s system to construct my own speeches.

John H. Fund wrote that while he was a a 15-year old high school student, Reagan taught him how he arranged his index card-based notes to tailor-make a speech for almost any audience. In 2011, Fund said he still used a variation of Reagan's system for his own speeches.

-

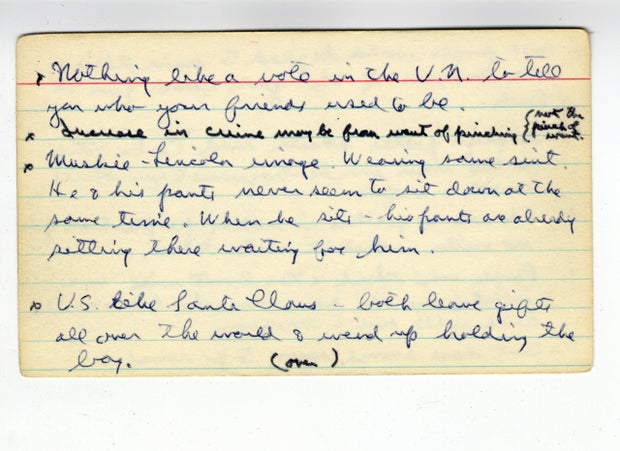

No such care in sourcing was needed for the time-tested jokes: “Those congressmen who worry about being bugged by the FBI—you’d think they’d be glad someone was listening to them.”

Reagan, however, did not source many of his one-liner jokes.

-

As one looks at the yellowing speech cards, one can see Reagan was always careful to include the documentation and source at the top. In his shorthand, you can see him quoting Thomas Jefferson: “If a nation expects to be ignorant & free in a state of civilizations, it expects what never was & what never will be.”

On many quote-based cards, Reagan was careful to cite his sources.

-

Indeed, Martin Anderson, Reagan’s former domestic policy adviser, says that Reagan’s system did wonders for his ability to give speeches. Reagan was able to approach a lectern with no sign anywhere of a prepared speech. Only those seated on the stage behind him could see his left hand drop into his suitcoat pocket and pull out a neat, small packet of cards and slip off the elastic band with his right hand as he set the cards down. And as for helping him in preparing the speech material, “his system was unrivaled,” Anderson remembers. “Before the speech Reagan would pore over the packs of cards, then pluck a few cards from one pack, a few from another, and combine them. In a matter of minutes, he would create an entirely new speech. The system was as flexible as a smooth gold chain.”

-

He compiled hundreds of them over the course of his career. Some were lost or given away as souvenirs, but 91 were recently discovered at the Reagan Library, stored in boxes that contained the contents of Reagan’s desk at his Los Angeles office on the day he died in June 2004.

Ronald Reagan compiled hundreds of index card-based notes over his career. Some were lost or given away as souvenirs, but 91 we discovered at the Reagan library (circa 2011). They were discovered among boxes which contained the contents of his Los Angeles office desk after his death in June 2004,

-

The cards would feature between five and 10 items and would be written on both sides in Reagan’s inimitable shorthand.

Ronald Reagan broke the typical rule to "write only on one side" of his index cards. His cards would typically have five to ten items written out by hand.