Rather than a homogenised rapid pace, the logic of temporal control fragments the pace of work and relies on the emergence of labour subjects who exist outside of the push for fast productivity.

- Apr 2025

-

nomadit.co.uk nomadit.co.uk

-

- Mar 2025

-

clarkdave.net clarkdave.net

-

wiki.postgresql.org wiki.postgresql.org

-

temporal_tables extension if you are in a pinch and want to use that for row versioning in place of a lacking SQL 2011 support.

-

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

- Jun 2024

-

-

for - Anthropocene - cross-scale spatial and temporal connectivity of water - governance - water - Anthropocene - cross scale - complexity - water governance - Anthropocene - from - Linked In post - new publication alart - to - Linked In post - new publication alert - Moving from fit to fitness for governing water in the Anthropocene

summary - This is a good review paper that summarizes findings from two decades of water research on river basins and watersheds, - It highlights how recent Anthropocene research shows the global interconnected nature of water systems, - which makes the traditional River Basin Organization form of local governance challenging since - variability in localities far from the governed river basin or watershed can have significant impact on it and vice versa - New governance systems must emerge to deal with this complexity

from - Linked In post - new publication alert - to - Linked In post - new publication alert - Moving from fit to fitness for governing water in the Anthropocene - https://hyp.is/GdXo1ipKEe-_FbMMhZGIMQ/www.linkedin.com/posts/activity-7207337444281659392-66RF/

Tags

- complexity - watershed management in cross-scale spatial and temporal connectivity of water

- from - Linked In post - new publication alert - to - Linked In post - new publication alert - Moving from fit to fitness for governing water in the Anthropocene

- complexity - governance - water - Anthropocene - cross scale

- anthropocene - cross-scale spatial and temporal connectivity of water

Annotators

URL

-

- May 2024

-

Local file Local file

-

“Listen to this,” he’d sometimes say, removing his headphones,breaking the oppressive silence of those long sweltering summer mornings.“Just listen to this drivel.” And he’d proceed to read aloud something hecouldn’t believe he had written months earlier.“Does it make any sense to you? Not to me.”“Maybe it did when you wrote it,” I said.He thought for a while as though weighing my words.“That’s the kindest thing anyone’s said to me in months”

In some way, this is like temporal parts -- how one can be completely A one day and then completely B the next

-

- Apr 2024

-

Local file Local file

-

A few hourslater, when I remembered that he had just finished writing a book onHeraclitus and that “reading” was probably not an insignificant part of hislife, I realized that I needed to perform some clever backpedaling and lethim know that my real interests lay right alongside his

Oliver wrote a book on Heraclitus, the main connector between his ideology, characterization, and the theory of universal flux, that one may not necessarily be one's past temporal part -- but one who continues it, like an illusion of movement.

-

- Mar 2024

-

off-planet.medium.com off-planet.medium.com

-

temporal conscientization” (becoming conscious of historical

for - definition - temporal conscientization - adjacency - temporal conscientization - Deep Humanity - poly-meta-perma-crisis - terror management - denial of death - Paolo Freire - denial of death - Ernest Becker - terror management - book - Critical Consciousness

definition - temporal conscientization - introduced by Paolo Freire n his book, temporal conscientization means becoming conscious of historical change, our - past, -present and - futures - For people to intervene in the movement of history, - people need to understand - how they got to where they are now, - the era that they are coming from, but as well to understand - the movements and potentialities of change that are leading to different futures.

adjacency - between - temporal conscientization - Deep Humanity - poly-meta-perma-crisis - terror management theory - denial of death - adjacency statement - Deep Humanity has always elevated the idea of knowing the past, present and future in order to frame meaning for navigating our future. - This is precisely the awareness of temporal conscientization. - Deep considerations of death, - and subsequently what meaning we can derive from life - is an integral part of the Deep Humanity exercise - A major theme of religions is the afterlife, or some continuation of consciousness after the process of death - In the context of temporal conscientization, - looking and - imagining - what our - individual and - collective future - looks like - the proposal of an afterlife is a terror management strategy to cope with our denial of death - Perhaps the emergence of the present poly-meta-perma-crisis is - a cultural indication to the collective intelligence of the human social superorganism that - the time has come to develop a mature theory of life and death that is - accessible to every member of our species so that - we can put the fragmenting, isolating existential question to rest once and for all

-

- Aug 2023

-

plato.stanford.edu plato.stanford.edu

- Dec 2022

-

www.sciencedirect.com www.sciencedirect.com

-

Tension management approaches and capabilities – definitions and key references.

Tension management scope: spatial separation, temporal separation, integration, analytical capability, executional capability, emotional capability, relational capability, balancing capability

-

- Apr 2022

-

www.cs.sfu.ca www.cs.sfu.ca

-

Focus your attention on the inner loops, where the bulk of the computationsand memory accesses occur.. Try to maximize the spatial locality in your programs by reading data objectssequentially, with stride 1, in the order they are stored in memory.. Try to maximize the temporal locality in your programs by using a data objectas often as possible once it has been read from memory.

为了写出有效率的程序,应该考虑哪些因素?

-

- Mar 2022

-

www.cs.sfu.ca www.cs.sfu.ca

-

Programs that repeatedly reference the same variables enjoy good temporallocality..For programs with stride-k reference patterns, the smaller the stride, thebetter the spatial locality. Programs with stride-1 reference patterns have goodspatial locality. Programs that hop around memory with large strides havepoor spatial locality..Loops have good temporal and spatial locality with respect to instructionfetches. The smaller the loop body and the greater the number of loop it-erations, the better the locality.

locality 总结起来的特点是什么?

-

- Jan 2022

-

spiral.imperial.ac.uk spiral.imperial.ac.uk

-

Elliott, P., Eales, O., Bodinier, B., Tang, D., Wang, H., Jonnerby, J., Haw, D., Elliott, J., Whitaker, M., Walters, C., Atchison, C., Diggle, P., Page, A., Trotter, A., Ashby, D., Barclay, W., Taylor, G., Ward, H., Darzi, A., … Donnelly, C. (2022). Post-peak dynamics of a national Omicron SARS-CoV-2 epidemic during January 2022 [Working Paper]. http://spiral.imperial.ac.uk/handle/10044/1/93887

-

-

-

Carmody, D., Mazzarello, M., Santi, P., Harris, T., Lehmann, S., Abbiasov, T., Dunbar, R., & Ratti, C. (2022). The effect of co-location of human communication networks. ArXiv:2201.02230 [Physics, Stat]. http://arxiv.org/abs/2201.02230

-

-

-

Liu, C., Yang, Y., Chen, B., Cui, T., Shang, F., & Li, R. (2022). Revealing spatio-temporal interaction patterns behind complex cities. ArXiv:2201.02117 [Physics]. http://arxiv.org/abs/2201.02117

-

- Aug 2021

-

library.scholarcy.com library.scholarcy.com

-

The Recorded Future system contains many components, which are summarized in the following diagram: The system is centered round the database, which contains information about all canonical event and entities, together with information about event and entity references, documents containing these references, and the sources from which these documents were obtained

-

We have decided on the term “temporal analytics” to describe the time oriented analysis tasks supported by our systems

RF have decided on the term “temporal analytics” to describe the time oriented analysis tasks supported by our systems

-

- Mar 2021

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

-

-

Karimi, Fariba, and Petter Holme. ‘A Temporal Network Version of Watts’s Cascade Model’. ArXiv:2103.13604 [Physics], 25 March 2021. http://arxiv.org/abs/2103.13604.

-

-

arxiv.org arxiv.org

-

Holme, Petter, and Jari Saramäki. ‘Temporal Networks as a Modeling Framework’. ArXiv:2103.13586 [Physics], 24 March 2021. http://arxiv.org/abs/2103.13586.

-

- Feb 2021

-

psyarxiv.com psyarxiv.com

-

Byrne, K. A., Six, S. G., Ghaiumy Anaraky, R., Harris, M. W., & Winterlind, E. L. (2020, November 5). Risk-Taking Unmasked: Using Risky Choice and Temporal Discounting to Explain COVID-19 Preventative Behaviors. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/uaqc2

-

- Oct 2020

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

teams establish shared temporal orders (and disorders) to orient around time

-

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

-

According to the endurantist view, material objects are persisting three-dimensional individuals wholly present at every moment of their existence

-

-

docs.google.com docs.google.com

-

-

But it’s really hard to see, because our human brains struggle to think about this Clock function as something for generating discrete snapshots of a clock, instead of representing a persistent thing that changes over time.

-

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

-

The perdurantist view is that an individual has distinct temporal parts throughout its existence.

-

- Sep 2020

-

-

Humphries, R., Mulchrone, K., Tratalos, J., More, S., & Hövel, P. (2020). A Systematic Framework of Modelling Epidemics on Temporal Networks. ArXiv:2009.11965 [Nlin, Physics:Physics]. http://arxiv.org/abs/2009.11965

-

- Aug 2020

-

psyarxiv.com psyarxiv.com

-

Ballard, Timothy, Ashley Luckman, and Emmanouil Konstantinidis. ‘How Meaningful Are Parameter Estimates from Models of Inter-Temporal Choice?’, 21 August 2020. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/mvk67.

-

- Jul 2020

-

-

Holme, P. (2020). Fast and principled simulations of the SIR model on temporal networks. ArXiv:2007.14386 [Physics, q-Bio]. http://arxiv.org/abs/2007.14386

-

- Jun 2020

-

-

Jazayeri, A., & Yang, C. C. (2020). Motif Discovery Algorithms in Static and Temporal Networks: A Survey. ArXiv:2005.09721 [Physics]. http://arxiv.org/abs/2005.09721

-

-

arxiv.org arxiv.org

-

Cai, L., Chen, Z., Luo, C., Gui, J., Ni, J., Li, D., & Chen, H. (2020). Structural Temporal Graph Neural Networks for Anomaly Detection in Dynamic Graphs. ArXiv:2005.07427 [Cs, Stat]. http://arxiv.org/abs/2005.07427

-

- May 2020

-

www.nature.com www.nature.com

-

Li, A., Zhou, L., Su, Q., Cornelius, S. P., Liu, Y.-Y., Wang, L., & Levin, S. A. (2020). Evolution of cooperation on temporal networks. Nature Communications, 11(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16088-w

-

- Apr 2020

-

cmmid.github.io cmmid.github.io

-

Russell, T.W., Hellewell, J., Abbott, S., Golding, N.,Gibbs, H., Jarvis, C.I., van Zandvoort, K., Flasche, S., Eggo, R., Edmunds, W.J., Kucharski., A.J. (2020, March 22). Using a delay-adjusted case fatality ratio to estimate under-reporting. CMMID Repository. https://cmmid.github.io/topics/covid19/global_cfr_estimates.html

-

-

cmmid.github.io cmmid.github.io

-

Russel, T.W., Hellewell, J., Abbott, S., Golding, N., Gibbs, H., Jarvis, C.I., van Zandvoort, K., Flasche, S., Eggo, R., Edmunds, W.J., Kucharski, A.J., (2020). Using a delay-adjusted case fatality ratio to estimate under-reporting. CMMID. https://cmmid.github.io/topics/covid19/severity/global_cfr_estimates.html

-

-

accessmedicine.mhmedical.com accessmedicine.mhmedical.com

-

The final stages of this sequence are caused by blood accumulation that forces the temporal lobe medially, with resultant compression of the third cranial nerve and eventually the brain stem.

-

- Mar 2020

-

geographicknowledge.de geographicknowledge.de

-

phd.rubensworks.net phd.rubensworks.net

-

Not only are public transport datasets useful for benchmarking route planning systems, they are also highly useful for benchmarking geospatial [13, 14] and temporal [15, 16] RDF systems due to the intrinsic geospatial and temporal properties of public transport datasets. While synthetic dataset generators already exist in the geospatial and temporal domain [17, 18], no systems exist yet that focus on realism, and specifically look into the generation of public transport datasets. As such, the main topic that we address in this work, is solving the need for realistic public transport datasets with geospatial and temporal characteristics, so that they can be used to benchmark RDF data management and route planning systems. More specifically, we introduce a mimicking algorithm for generating realistic public transport data, which is the main contribution of this work.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

- Apr 2019

-

hypothes.is hypothes.is

-

La accion del musculo temporal es de elevar la mandibula y dirigirla hacia atras, de esta ultima actividad se encargan los haces posteriores del temporal

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

- Feb 2019

-

bop.dacoruna.gal bop.dacoruna.gal

-

b) Contrato por esixencias circunstanciais do mercado, acumulación de tarefas ou exceso de pedidos:Para este tipo de contrato acordase que terá unha duración máxima de 12 meses nun período de 18 meses

-

- Jan 2019

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

the field. Such a fresh approach possibly improves a wide range of conceptual issues in disasters and hazards. In addition, such an approach would give us insights on how disaster managers, emergency responders, and disaster victims (recognizing that these “roles” may overlap in some cases) see, use and experience time. This, in turn, could assist with a number of applied issues (e.g., warning, effective “response,” priorities in “recovery”) throughout the process of disaster.

Neal cites his 1997 paper about the need to develop better categories to describe disaster phases. Here, her attempts to work through those classifications with a sociotemporal bent.

Evokes Bowker and Star's work on classification and boundary objects/infrastructures but also Yakura (2002) on temporal boundary objects.

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

Temporal differentiation helps substantiate elusive mental distinctions. Like their spatial counterparts, temporal boundaries often represent mental partitions and thus serve to divide more than just time.

Temporal boundaries (and the objects inherent in them) are used to convey additional meaning and context. These partitions are used to describe historical distinctions ("The Great Depression", "Vietnam Era"), life distinctions (work vs private time vs religious observance).

Examples above are from the chapter.

-

- Dec 2018

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

eople prefer to know who else is present in a shared space, and they usethis awareness to guide their work

Awareness, disclosure, and privacy concerns are key cognitive/perception needs to integrate into technologies. Social media and CMCs struggle with this knife edge a lot.

It's also seems to be a big factor in SBTF social coordination that leads to over-compensating and pluritemporal loading of interactions between volunteers.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

- Oct 2018

-

-

We want to make our model temporally-aware, as furtherinsights can be gathered by analyzing the temporal dy-namics of the user interactions.

sounds exciting

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

- Aug 2018

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

create the effect of temporal symmetry, of the group sharing a moment, even though individual members clearly read the message at different moments.

description of temporal symmetry

-

The notion of temporal structuring views "real time" not as an inherent property of Internetbased activities, or an inevitable consequence of technology use, but as an enacted temporal structure, reflecting the decisions people have made about how they wish to structure their activities, both on or off the Internet. As an alternative to the idea of '·real time," Bennett and Wei II ( 1997) have suggested the notion of "real-enough time," proposing that people design their process and technology infrastructures to accommodate variable timing demands, which are contingent on task and context. We believe such "real-enough" temporal structures are important areas of further empirical investigation, allowing us to move beyond the fixation on a singular, objective "real time" to recognize the opportunities people have to (re)shape the range of temporal structures that shape their lives.

real time vs real-enough time

-

The notion of temporal structuring we have developed here suggests instead that people enact multiple, heterogeneous, and shifting temporal structures in all aspects of their lives.

people experience temporal structures as dynamic

-

Our empirical example also highlighted the value of achieving virtual temporal symmetry for members of a geographically dispersed community. As electronic media become increasingly central to organizational life, individuals may use asynchronous media in various ways to shape devices of virtual symmetry that help them coordinate across geographical distance and across multiple temporal structures. This suggests that when studying the use of electronic media, researchers should pay attention to the conditions in which virtual temporal symmetry may be enacted to coordinate distributed activities, and with what consequences. Interesting questions for empirical research include the following. As work groups in organizations become more geographically dispersed and/or more dependent on electronic media, do members enact virtual temporal symmetry for certain purposes? If so, for which types of purposes? And how? If not, how do such work groups achieve temporal coordination?

virtual coordination across geographic distance via electronic media and how it shapes/is shaped by temporal structures

-

By examining a community's repertoire of temporal structures, we can understand the variety of ways in which community members' actions (re)produce the different temporal structures they constitute through their ongoing practices

A good justification for the SBTF study.

-

The notion of temporal structuring focuses attention on what people actually do temporally in their practices, and how in such ongoing and situated activity they shape and are shaped by particular temporal structures. By examining when people do what they do in their practices, we can identify what temporal structures shape and are shaped (often concurrently) by members of a community; how these interact; whether they are interrelated, overlapping, and nested, or separate and distinct; and the extent to which they are compatible, complementary, or contradictory.

Different interaction patterns of temporal structures that are shaped by people and shape people's activities.

-

In all these cases, the notion of temporal structuring through ongoing practices helps us understand and bridge the temporal oppositions underlying the research literature. We tum now to an empirical example to demonstrate how this perspective can offer a new understanding of the temporal conditions and consequences of organizational life.

Succint summation of previous section and transition.

-

In practice, however. an open-ended or closed temporal orientation is not a stable property of occupational groups, but an emergent property of the temporal structures being enacted at a given moment by the groups' members.

describes how a group orients around an emergent property of temporal structures depending on context.

Orlikowski and Yates write later in this passage:

"Moreover, point of view and moment of observation may also affect the type of structuring observed."

-

Viewed from a practice perspective, the distinction between cyclic and linear time blurs because it depends on the observer's point of view and moment of observation. In particular cases, simply shifting the observer's vantage point (e.g., from the corporate suite to the factory floor) or changing the period of observation (e.g., from a week to a year) may make either the cyclic or the linear aspect of ongoing practices more salient.

Could it be that SBTF volunteers are situating themselves in time as a way to respond to a cyclic/linear tension? or a spatial tension?

-

An emphasis on the cyclic temporality of organizational life also underpins the work on entrainment, developed in the natural sciences and gaining currency in organization studies. Defined as "the adjustment of the pace or cycle of one activity to match or synchronize with that of another" (Ancona and Chong 1996, p. 251 ), entrainment has been used to account for a variety of organizational phenomena displaying coordinated or synchronized temporal cycles (Ancona and Chong 1996, Clark 1990, Gersick 1994, McGrath 1990).

Entrainment definition.

-

In spite of the general movement from particular towards universal notions of time (Castells 1996, Giddens 1990, Zerubavel 1981 ), we can see that in use, all uni versa! temporal structures must be particularized to local contexts because they are enacted through the situated practices of specific community members in specific locations and time zones.

Cites Castells (networks), Giddens (structuration) and Zerubavel (semiotics) as moving away from particular time to more universal notions of real-time, 24-hour clock, and calendars, respectively.

Orlikowski and Yates argue that even universal notions need situated and contextual practices to make sense of time.

-

One such opposition is that between universal (global, standardized, acontextual) and particular (local, situated, contextspecific) time.

Orlikowski and Yates describe situated, contextual time as particular.

-

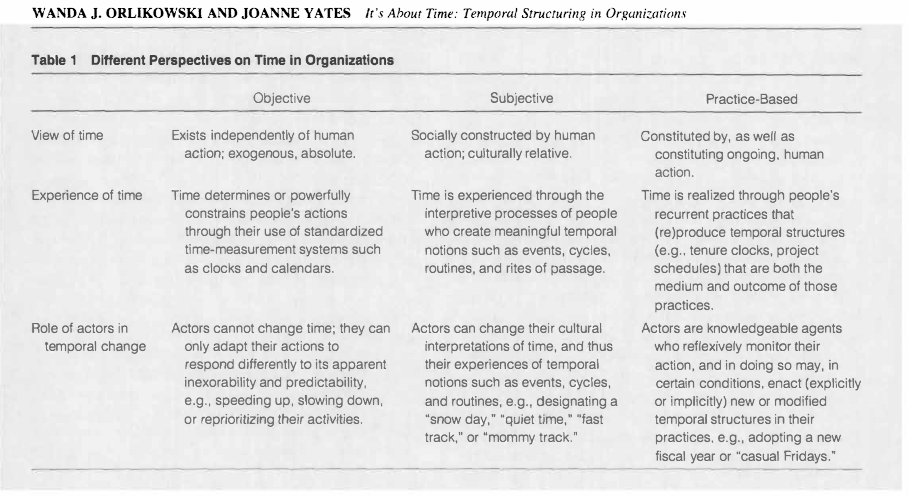

Table 1 Different Perspectives on Time in Organizations

Objective vs Subjective vs Practice-based perspectives in time

-

That is, people are purposive, knowledgeable, adaptive, and inventive actors who, while they are shaped by established temporal structures, can also choose (whether explicitly or implicitly) to (re)shape those temporal structures to accomplish their situated and dynamic ends.

People can enact their agency through practices, habits or planned intentions to change temporal structures against what frequently feels like an external time that operates independently.

-

scholars have begun to recognize the importance of what Nowotny (1992, p. 424) has termed pluritemporalism"the existence of a plurality of different modes of social time(s) which may exist side by side." Our structuring lens sees this not so much as the existence of multiple times, but as the ongoing constitution of multiple temporal structures in people"s everyday practices.

Cites Nowotny's pluritemporalism.

Orlikowski and Yates interpret this as enacting multiple temporal structures that are often interdependent and can also be in conflict. Raises the example of tensions between work and family temporal structures.

-

Like social structures in general (Giddens 1984 ), temporal structures simultaneously constrain and enable.

The paper provides an example of how work vacations and office schedules are restricted during certain seasons, and more open in other seasons.

-

While adopting one side or the other of this dichotomy may offer researchers analytic advantages in their temporal studies of organizations, difficulties arise when these positions are treated-not as conceptual tools-but as inherent properties of time. Focusing on one side or the other misses seeing how temporal structures emerge from and are embedded in the varied and ongoing social practices of people in different communities and historical periods, and at the same time how such temporal structures powerfully shape those practices in turn. By focusing on what organizational members actually do, our practice-based perspective on temporal structuring may offer new insights into how people construct and reconstruct the temporal conditions that shape their lives.

Nice summation of how practice-based experiences of time are not well-served by treating the objective-subjective dichotomy as properties of time.

Need for a different perspective to explore other emergent ways people engage with or experience time.

-

Thus temporal structures, like all social structures (Giddens 1984), are both the medium and the outcome of people's recurrent practices.

Wrapping Giddens' structuration theory into the concept of temporal structures.

-

This integration suggests that time is instantiated in organizational life through a process of temporal structuring,1 where people (re)produce (and occasionally change) temporal structures to orient their ongoing activities.

Succinct definition of temporal structures.

-

We contribute to this discussion within organizational research by offering an alternative third view-that time is experienced in organizational life through a process of temporal structuring that characterizes people's everyday engagement in the world. As part of this engagement, people produce and reproduce what can be seen to be temporal structures to guide, orient, and coordinate their ongoing activities.

How the concept of temporal structures fits in the literature.

-

emporal structures here are understood as both shaping and being shaped by ongoing human action, and thus as neither independent of human action (because shaped in action), nor fully determined by human action (because shaping that action). Such a view allows us to bridge the gap between objective and subjective understandings of time by recognizing the active role of people in shaping the temporal contours of their lives, while also acknowledging the way in which people's actions are shaped by structural conditions outside their immediate control.

Temporal structures definition

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

Third, the use of time and temporality for mak-ing and giving sense to unfinalized stories, antenar-ratives and future scenarios (see Boje 2011), includ-ing attention to issues, such as temporal depth, timeurgency and temporal orientation in promoting theneed for short or long-term strategies (see Jabri 2016,p. 97; Kunischet al. 2017, p. 1043)

Future research direction: Temporal depth // Tempo

See: Bluedorn 2002

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

A promising approach that addresses some worker output issues examines the way that workers do their work rather than the output itself, using machine learning and/or visualization to predict the quality of a worker’s output from their behavior [119,120]

This process improvement idea has some interesting design implications for improving temporal qualities of SBTF data: • How is the volunteer thinking about time? • Where does temporality enter into the data collection workflow? • What metadata do they rely on? • What is their temporal sensemaking approach?

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

User studies and intuition both suggest that the activities that a knowledge worker engages in change—sometimes dramatically—over time. Projects and milestones come and go, and the tools and information resources used within an activity often change over time as well. Furthermore, activities completed in the past and their outcomes often impact activities in the present, and ongoing activities will, in turn, affect activities that will be undertaken in the future. Capturing activity over the course of time has long been a problem for desktop computing.

"Activities are dynamic"

This challenge features temporal relationships between work and worker, in the past/present sense, and work and goals, in the present/future sense.

Evokes Reddy's T/R/H temporal organization of work and Bluedorn's work on polychronicity.

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

This means also that the predominantly linear time is comp-lemented by greater awareness of cyclical times and temporal routines which are overlapping each other.

Evokes Adam's timescape concepts of other shapes/dimensions beyond linear/clock time experiences.

This passage also seems to touch on Reddy et al's focus on temporal rhythms as an activity strategy

-

ut it will also have to come to terms with confronting 'the Other' (Fabian, 1983), with 'the curious asymmetry' still prevailing as a result of advanced industrial societies receiving a mainly endogenous and synchronic analytic treatment, while 'developing' societies are often seen in exogenous, diachronic terms. Study of 'Time and the Other' presupposes, often implicitly, that the Other lives in another time, or at least on a different time-scale. And indeed, when looking at the integrative but also potentially divisive 'timing' facilitated by modern communication and information-processing technology, is it not correct to say that new divisions, on a temporal scale, are being created between those who have access to such devices and those who do not? Is not one part of humanity, despite globalization, in danger of being left behind, in a somewhat anachronistic age?

Nowotny argues that "the Other" (non-western, developing countries, Global South -- my words, not hers) is presumed to be on a different time scale than industrial societies. Different "cultural variations and how societal experience shapes the construction of time and temporal reference..."

This has implications for ICT devices.

-

At present, information and communication technologies con-tinue to reshape temporal experience and collective time consciousness (Nowotny, 1989b)

Get this paper.

Nowotny, H. (1989b) 'Mind, Technologies, and Collective Time Consciousness', in J. T. Fraser (ed.) Time and Mind, The Study of Time VI, pp. 197-216. Madison, CT: International Universities Press.

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

Although the spatio-temporal variation in rumor quantity and content has long been of interest to thefield, collecting data that accounts for temporalandspatial characteristics of rumoring has been extraordinarily difficult to dowith any degree of precision. Some have been able to capture rumoring data with some degree of temporal precision (Bordiaand Rosnow, 1998; Danzig, 1958; Greenberg, 1964) or with some spatial precision (Larsen, 1954), but bridging the two hasbeen difficult. Synthesizing temporal and spatial rumoring data across a wide variety of events had long been beyond thecapabilities of researchers. Simply gathering reliable data on rumoring was already fraught with challenges.

Check these citations on difficulty of temporal data capture. Since they are all quite old studies (between 20-60 years old), I question how relevant they are to current behavior -- either offline or online.

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

“Since one cannot distinguish a figure without a background, the present does not meaningfully exist without a past” (emphasis added; 2001, p. 608). As the background, the past provides a benchmark for the present against which comparisons can be made. And such comparisons indicate whether the present is the same as the past or different from it.

Relationship between present and past for sensemaking and meaning.

Later Bluedorn notes that interpretation and understanding of the past can be applied to a similar present. If they are different, then "the past provides a context, a frame for the present, and the linkages with the past provide an explanation for the present by suggesting how the present came to be, which makes the present more understandable, more meaningful."

The question then becomes which past -- how long ago (its temporal depth) is compared to the present (or future) for sensemaking.

-

So connections and the meaning they generate are fundaThe Best of Times and the Worst of Timesmental, which is why the loss of meaning is so troubling—the systematic loss of meaning even more so.

Fundamental temporality of connections definition.

How two factors -- speed/tempo and temporal depth of an experience generate meaning.

-

“the dynamic weaving of events, interactions, situations, and phases that comprise those relationships” (2000, p. 27), the dynamic weaving of events, interactions, and situations being very similar to narrative.

Temporal context definition.

Furthers the notion of narrative and how relationships between events/things is transformed into a cohesive whole which is necessary for sensemaking.

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

Personal and organizational histories occupy prominent figure positions in the figure-ground dichotomy, and that such histories are used to cope with the future is indicated by several pieces of evidence.

Does this help to explain the need for SBTF volunteers to situate themselves in time -- as a way to construct a history in Weick's "figure-ground construction" method of sensemaking for themselves and to that convey sense to others?

-

Temporal focus is the degree of emphasis on the past, present, and future (Bluedorn 2000e, p. 124).

Temporal focus definition. Like temporal depth, both are socially constructed.

Cites Lewin (time perspective) and Zimbardo & Boyd.

-

The results presented in Bluedorn (2000e) and the Appendix consistently support the distinction between temporal depth and temporal focus. Conceptually the two terms refer to different phenomena, and empirical measures of the two share so little variance in common that for practical purposes they can be regarded as orthogonal. Temporal depth is the distance looked into past and

Differences between temporal depth vs temporal focus are orthogonal -- two separate conceptual ideas and refer to different phenomena.

Depth = "distance looked into the past and future" Focus = "importance attached to the past, present and future"

-

However, Boyd and Zimbardo’s interest was not in comparing short-, mid-, and long-term temporal depths; rather, it was in examining the degree to which people were oriented to a transcendental future, and in examining the extent to which this variation covaried with other factors such as age, gender, and ethnicity. This is a natural extension of the questions involved in research on general past, present, and future temporal orientations (e.g., Kluck- hohn and Strodtbeck 1961, pp. 13-15), orientations that at first glance appear similar to issues of temporal depth. However, as I have argued elsewhere in opposing the use of the temporal orientation label, these general orientations are more an issue of the general temporal direction or domain that an individual or group may emphasize (Bluedorn 2000e) than the distance into each that the individual or group typically uses. The latter is the issue of temporal depth; the former, what I have called temporal focus (Bluedorn 2000e)

Comparison of Bluedorn's thinking about temporal depth vs temporal focus instead of framing it as a temporal orientation (the direction/domain that an individual or group emphasizes in sensemaking).

ZImbardo and Boyd use the phrase "time perspective" rather than temporal orientation

-

And the determination of organizational age illustrates the constructed, enacted nature of the past, because what at first glance seems like a simple, even objective matter becomes ambiguous when mergers and acquisitions are involved. Is the founding date the date that the oldest of the merger partners began operations, or is it the date when the last partners merged? Families can face the same ambiguities when one or both spouses have been married previously and they and their children combine to form new families. As the definition of the situation principle teaches (see Chapter 1), the important issue is when the people in the organization or family believe it was founded.

Ambiguity about "founding date" of a merged organization is akin to the friction point for SBTF data collection -- is the date/timestamp the original social media post or the shared post (either of which may occur at different points in the stream). What is the boundary?

-

Steve Ferris and I found that organizational age was positively correlated with both past and future temporal depths, and that these relationships persisted after controlling for several organizational and environmental variables (Bluedorn and Ferris 2000). The older the organization, the further its members looked into both the past and the future, and the positive temporal depth correlations with the organization’s age may suggest why

Bluedorn argues that "organizational past apparently becomes received history" which is also socially constructed, interpreted and potentially inaccurate.

Having a longer history provides an organization with a longer timescape to imagine its past and future.

-

The past leads to and influences the future, but the future does not influence the past.Thus El Sawy s research provided a second clue that past and future are related, and it even added a causal direction (i.e., “A connection to the past facilitates a connection to the future” [March 1999, p. 75])·

Study demonstrates "time's arrow" that the past influences future but not the other way around.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arrow_of_time

This idea also contributes to a spatial sense of time in Western cultures as "behind", "forward", "ahead", etc. Eastern and Global South cultures do not share this spatial representation.

-

the result is a statistically significant positive correlation (see the Appendix). The proposed connection is accurate: The longer the respondent’s past temporal depth, the longer the respondent’s future temporal depth.

Past temporal depth and future temporal depth are positively connected. The longer the past perception, the longer the future perception.

This is true for both individuals and groups.

-

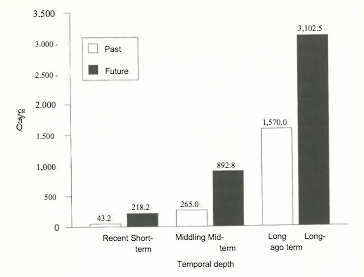

Perhaps the most noteworthy of the differences is that each of the future regions extends much further into the future than their past counterparts extend into the past. The short-term future extends about five times further than does the recent past; the mid-term future, about three-and-one-third times as far as the middling past; and the longterm future, about twice as far as the long-ago past. So although the steplike pattern is similar for both the past and future regions, the future depths extend over substantially larger amounts of time than do those in the past

Comparing respondents' differences in temporal depth of past vs future. A person's perception of future is considerably longer than their perception of the past.

-

the temporal distances into the past and future that individuals and collectivities typically consider when contemplating events that havehappened, may have happened, or may happen.

Temporal depth definition -- applies to individuals as well as groups.

It considers time in two directions (past and future)

-

- Jul 2018

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

So does polychronicity scale? Or is it a nested phenomenon whereby someone might be monochronic within hour- long intervals but polychronic when the frame enlarges to a month? And if so, what might be the consequences of different nesting combinations?

3rd wave: Does polychronicity scale over time periods larger than a daily work setting? Does it change depending upon the temporal trajectory, rhythm, or horizon?

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

er. Each of these choices reflect power dynamics and conflicting tensions. Desires for ‘presence’ or singular focus often conflict with obligations to be responsive and integrate ‘work’ and ‘life

Are these power dynamics/tensions: actor or agent-based? individual or technical? situational or contextual? deliberate or autonomous?

-

How do we understand such mosaictime in terms of striving for balance? Temporal units are rarely single-purpose and their boundaries and dependencies are often implicit. What sociotemporal values should we be honoring? How can we account for time that fits on neither side of a scale? How might scholarship rethink balance or efficiency with different forms of accounting, with attention to institutions as well as individuals?

Design implication: What heuristics are involved in the lived experience and conflicts between temporal logic and porous time?

-

Our rendering of porous time imagines a newperspective on time, in whichthe dominant temporal logic expandsbeyond ideals of control and mastery to include navigation(with or without conscious attention) of that which cannot be gridded or managed: the temporal trails, multiple interests, misaligned rhythms and expectations of others.

Design implication: How to mesh temporal logic with porous time realities?

-

Taken together, an orientation to time as spectral, mosaic, rhythmic (dissonant),and obligatedsuggestsa possible alternate understanding of what time is and how it can work.An initial typology ofporous time honors the fluidity of time and its unexpected shifts; it also acknowledges novel integrations of time in everyday practice. Addressingthese alternate temporal realities allows us to build on CSCW’s legacy of related research to questionthereach and scope of thedominant temporal logic.

Description of porous time and its elements as an extension of CSCW literature on temporal logic.

-

Yet, thepromise of social control affordedby information and communication technologies belies the inadequacy ofthe dominant temporal logic.

Design implication: Re-aligning real time needs/pressures/representations with temporal logic.

-

In contrast to the assumption oftime as linear, with ordered chunks progressing ina straightforward manner, people often negotiate time rhythmically, arranging timein patterns and tempos that do not always co-exist harmoniously. In line with earlier CSCW findings [e.g., 4, 9, 45, 46], we term thisrhythmic time, which acknowledges both the rhythmic nature of temporal experience as well a potential disorderliness or ‘dissonance’ when temporal rhythms conflict.Like mosaic time, bringing dissonant rhythms into semi-alignment requires adaptation, work, and patience.

Rhythmic time definition. Counters the idea of linear time.

How does this fit (or not) with Reddy's notion of temporal rhythms?

-

In alignmentwith Reddy and Dourish’s concept of temporal trajectory [45], spectral time suggests that temporal experience is more than a grid of accountable blocks; multiple temporalities create flowsthat often defy both logical renderingand seamless manipulation

Spectral time is linked to Reddy's idea of temporal trajectory.

-

bels. To date, we have found that our subjects have a minimal ability, and almost no language, to discuss the vagaries of time. In general, people attempt to negotiate their subjective experiences of time through the assumptions of the dominant temporal logic outlined a

So true, in my study too.

Cite this graf.

-

In witnessing how people struggle toorient to the dominant temporal logic,we find it isinsufficient to encapsulate temporal experiences. Thus, we now theorizea set of expanded notions, an initial typology that we call ‘porous time’.

Definition of porous time.

Elements of porous time include: spectral, mosaic, rhythmic and obligated.

-

One of the ways that a temporal logic becomesvisible for analysis and critique is through the tensions that emerge when its assumptions and norms do not align with daily experience. In our collective fieldwork we have observedmultiple examples of mundane dailypractices coming into conflict withthe logic that time is, or should be, chunk-able, singular purpose, linear, and/or owned.These tensionshelp bring to the fore the extent of the dominant temporal logic and showcase the inadequacy of this narrow set of assumptions to fully describetemporal experiences.

This section of the paper focuses on tensions in temporal logic that lead to the new typology of "porous time".

These tensions give rise to conflicts in how people's activities don't align with the logic of how they should/could allot, manage and/or own their time.

"The road to hell is paved with good intentions and bad calendaring?"

-

We call this prevailing temporal logic ‘circumscribed time.’ We use this label to highlight the underlying orientation to time as a resource that can, and should, be mastered. A circumscribed temporal logic infers that time should be harnessed into ‘productive’ capacity by approaching it as something that can be chunked, allocated to a single use, experienced linearly, and owned. In turn, the norms of society place the burden on individuals to manage and ‘balance’ time as a steward, optimizing this precious resource by way of control and active manipulation.

Description of the elements of circumscribed time.

-

Finally,time is understood asaresource that is owned by an individual and thus needs to be managed and apportioned by that individual.Like personal income, time is a resource that the individual has both the burden and responsibility to manage well. This vision of time reflects an assumption there are ‘better’ or ‘worse’ ways to use, spend and save time and it is up to the individual to engage in practices of temporal ownership. Controlling time doesnot suggest thatan individual can speed up or slow down time, but rather,suggeststhat timecan be personally configured to meet individual aims or goals.

Definition of time as ownable.

This idea of time as a resource also denotes a certain sense of personal agency/control over time when certain practices, like scheduling or efficiencies, are applied.

-

Thedominant temporal logicalso conceptualizestime aslinear. In other words,one chunk of time leads to another in a straight progression. While chunks of time can be manipulated and reordered in the course of a day (or week, or month), each chunk of time has a limited duration and each activity has a beginning and an end. An hour is an hour is an hour, and in the course of a day (or a lifetime) hours stack up like a vector, moving one forward in a straightforward progression.

Definition of linear time.

WRT to temporal linguistics, linear time drives moving-ego and moving-time metaphors.

-

Aligned with chunk-able time is the assumption that each chunk of time, or its particular gridded arrangement, is allocated to a single purpose.

Definition of single purpose time.

Design implication: How does single-purpose time align or conflict with multitasking and/or blurred task types that overlap home vs office, personal vs professional.

-

appointment. Time chunksopen up the possibility for future-oriented temporal manipulation and valuation; they assumethat we are able to know, in advance, the duration of tasks and experiences.

How does the idea of time chunks and future-orientation fit with:

Reddy's temporal horizon concept? Zimbardo's future time perspective?

-

The expectation that time is chunk-able is conditioned by an understanding that time exists in units (a second, a minute, a year) and that temporal units are equal–that can be swapped and exchanged with relative ease.

Definition of chunkable time.

Design implication: Time is experienced in consistent, measurable, and incremental units.

Ex: 60 minutes is always 60 minutes no matter what part of the day it occurs or in any social context, such as calendaring/scheduling an event.

Using a chunkable time perspective, we conform our activities/appointments to clock-time increments rather than making the calendar conform. Per Mazmanian, et al., this perspective "perpetuates a sense that time is malleable and responsive" with little concern about how changing an appointment time can affect the rest of the calendar.

-

the nature of timethat reflect a dominant temporal logic –specifically that timeischunkable, single-purpose, linearandownable

4 aspects of circumscribed time

describes time as a resource that can be mastered incrementally.

-

A temporal logicoperatesat multiple levels. It is perpetuated insocialand cultural discourse; is embedded in institutional expectations and policies; drivesthe design and implementation of technologies;establishes resilient social norms; and provides a cache of normative, rational examples to draw on when individuals needtomake sense of their everyday engagements with time. When a tool like Microsoft Outlook is designed, presented, and justified in a marketing campaign it is both reflecting and perpetuating atemporal logic.

Design implication: How temporal logic informs and influences other behaviors.

-

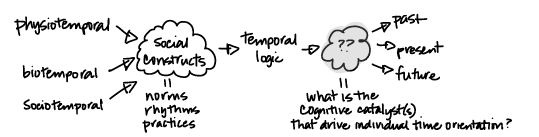

In particular, by temporal logicwe mean the socially legitimated, shared assumptions about time that areembedded in institutional and societal norms, discourses, material and technological processes, and shared ideologies. A temporal logic defines what is rational, normal and expected, andimbues a society with a definitionof what time is that directsindividuals in how they should operate in and through time.It provides an understanding of time that becomes so embedded that it seems to define reality.

Definition of temporal logic as a shared understanding that leads to social constructs of common practices, rules, and norms.

-

What would it look like to more explicitly acknowledge power dynamics in information and communication technologies? In the tradition of critical and reflective design [50], how might CSCW scholarship think about designing technologies that ‘protect’ users from temporal obligations and render messiness and disorganization a possible way of engaging with time?

Design implication: What if porous time was considered a feature not a bug?

How to better integrate personal agency/autonomy and values into a temporal experience?

How could a temporal artifact better support a user flexibly shifting/adapting temporal logic to a lived experience?

-

Interrogating the temporal logic of circumscribed time raises three related sociotemporal concerns particularly relevant to CSCW: lived experience, visions of success, and power relations. We address each concernin relation to key theoretical works to showhow the insights presented here both point tothe limitations of the dominant temporal logic of circumscribed time and demandexpanding this logic to include those orientations suggested by porous time.

3 sociotemporal concerns that help bridge circumscribed and porous time: lived experience, visions of success and power relations.

-

The temporal logic of circumscribed time falls short of describing, let alone organizing, the complex temporalities that govern American lives today. As an expansion of the dominant logic, porous time aims toprovide a more nuanced account of howtemporality shapes interactions among people, technologies, and the

The tension between circumscribed and porous time leads to control-seeking and a need to adapt to the "fluidities of time".

This tension serves up different coping mechanisms, such as: metaphors, time representations, design challenges, routines, need for self-reflection, quantification via scheduling, data collection, technical solutions, predictive models, etc.

-

We find and name an emergent set of temporal elements–spectral, mosaic,rhythmicand obligatedtime–which implicitly challenge the assumptions of the dominant logic. We call this collective set ‘porous time.’

Definition of porous time and the set of temporal elements that challenge the dominant logic.

-

s ‘circumscribed time.’This logic, which is embedded in many popular tools, current scholarship,and especially in the discourse of time management, is characterized by assumptions that time is chunk-able(i.e. unitized and measurable), oriented to a single purpose, experiencedlinearly, and owned by individuals

Definition of circumscribed time -- a dominant temporal logic.

-

temporal logic–a particular orientation to time that manifests in time-related social norms, moral judgments, daily practices, and technologies for scheduling and coordinat

Definition of temporal logic

Tags

- temporal logic

- linear time

- sociotemporality

- circumscribed time

- spectral time

- temporal trajectory

- chunkable time

- temporal horizon

- language of time

- rhythmic time

- time metaphor

- porous time

- single purpose time

- ownable time

- power dynamics

- future time perspective

- temporal rhythm

- design implication

- lived experience

- rhythm

Annotators

URL

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

The amount of time we are willing to devote to the various relations in which we are involved and organizations to which we belong clearly reflects the level of our commit- ment to each of them

Could this account for how/why SBTF volunteers use personally situated time references to signal how long they can be available/devote to an activation?

Is this a semiotic version of Reddy's temporal trajectory?

Motive expressed through "duration" seems to be fairly well determined for Wikipedia editors, per Kittur/Kraut/Resnick chapters. I don't see why it wouldn't also apply to SBTF.

-

Timing as a

Could the multiple temporalities that symbolize importance account for a source of tension between always online volunteers and those who show up for random periods of time?

Deployments have fixed time periods for data collection but no scheduling mechanisms for volunteers. Does this create a source of friction when there is no mechanism to signal social intent or meaning?

How does this problem get reflected in Reddy's TRH model or Mazmanian's porous time idea?

How can you manage social coordination of rhythms/horizons when there is no signal to convey intent/commitment?

What part of the SBTF social coordination is spectral, mosaic, rhythmic and/or obligated? And when is it not?

-

Temporal contrasts can be used not only to substantiate abstract conceptual contrasts but also to help accentuate actual social and political ones (Zerubavel 1985, pp. 47, 71-7

How are these contrasts represented? Does Bergson's paper reflect this idea?

Look up citation: Zerubavel.1985. The Seven-Day Circle

-

implies the virtual inseparability of semantics from syntactics, and, indeed, Saussure's followers are often quite appropriately called structuralists, as they view signs not so much in terms of their substantive "content" as in terms of the ways in which they are formally related to other signs (i.e., in terms of the structure of the symbolic system to which they belong). More specifically, they tend to focus particularly on the formal relation of opposition or contrast, because, "in any semiological system, whatever distin- guishes one sign from the oth

What is the SBTF structure? What differentiates it?

Do the temporal signs for data collection contrast/differ enough from the temporal signs for the crowd process to describe a single structure for digital humanitarian work?

Data time = desire for real time information where units of data have their own time contexts (meta data, periods, timelines, qualitative representations/metaphors, etc.)

Process time = acceptance that work time is always 24/7, urgent and feels like a step behind. The people who perform the process also have their own time contexts (personally situated time, trajectories, rhythms, horizons, etc.)

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

Consequently, efforts to design for temporal experience must do more than simply build desirable temporal models into technologies.

Quote this for CHI paper.

-

In their view, time is both independent of and dependent on behaviour: temporal structures are produced and reproduced through everyday action, and these in turn shape the rhythm and form of ongoing practices. Existing temporal structures become taken for granted and appear to be unbending, but time is also treated as malleable in that temporal structures can be changed and new ones estab-lished. The objective/subjective dichotomy is not inherent to the nature of time, but is a property of the particular tem-poral structures being enacted at a particular moment. They call for a focus on examining how temporal structures be-come established for a particular activity, and how they are sustained, reinforced or modified in practice.

Org studies perspective on temporal structures.

Does this have some implications for Reddy's paper on trajectories/rhythms/horizons?

-

Designing for an alternative temporal experience means understanding the ways in which multiple temporali-ties intersect, whether these frame a person’s working day, or allow a family to spend time together. While scheduling technologies do of course have a role to play here [see e.g. 31], many of the temporal structures that frame everyday life are not so much scheduled as unfold in a way that isunremarkable [54], or are so firmly established that they are no longer seen as alterable.

Design implication: To integrate multiple temporalities into technology we need to reconsider temporal structures -- or the patterns of social coordination that we use as rules, rhythms, habits, and practices that guide activity.

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

sregarded. Temporal Design attempts to counteract these effects by drawing attention to social practices of time. Time is a social process, tacitly defined through everyday practices. It is rehearsed, learned, designed, created, storied, and made. This aspect however is often overlooked not only by designers, but also by society in general. Designers can have a key role in unlocking the hegemonic narratives that restrict cultural understandings of time and in opening up new ways of making, living and thinking

Description of temporal design and its purpose.

-

As the original visions for Slow Design and Slow Technology suggest, the world is comprised of multiple temporal expressions, which play important roles in our lives, even if disregarded within dominant accounts of what ti

What are the "multiple temporal expressions?" Examples would help here.

Note to self: Use more explicit language, case examples, etc., to avoid reviewers' incorrectly filling in the gaps or misinterpreting an already cagey subject that's hard to pin down.

-

The documentation of routines invited the students to reflect on the multiplicity of practices that shape temporality inside the school community, making the social layering of time more perceptible. Far from being restricted to timetables, buzzers and timed tasks, school time is a fusion of personal times, rhythms and temporal force

This graf and the next, might be helpful for the Time Machine Project study. Cites: Adam on description of "school time."

-

While the Printer Clock focused on emphasising the embodied and situated nature of time, pointing to the mesh of activities and characters that come together to create time, the TimeBots drew attention to personal rhythms and how they played out within the context of the classroom

Pschetz, et al., also use idea of "situated time."

-

e students. The TimeBots interacted with each other on a different level, revealing the subjective timescap

Adam's timescape concept as applied to a group during social coordination.

-

4.3.3 TimeBotsWhile the Printer Clock focused on emphasising the embodied and situated nature of time, pointing to the mesh of activities and characters that come together to create time, the TimeBots drew attention to personal rhythms and how they played out within the context of the classroom. The aim was to challenge the idea that the world is in a state of constant acceleration by inviting children to reflect on the multiple speeds of their day. In contrast to the slow movement, which assumes acceleration as a universalised condition and attempts to counteract this condition by promoting opportunities to slow down, the intention here was to invite the students to explore the variant speeds at which they l

Does this idea map with Reddy's premise about temporal trajectories, rhythms, and horizons?

-

ast. Moving from a quantitative time to a qualitative one, the Printer Clock tells time through the activities of others and the variety of pictures reveals the multiplicity of rhythms within that

Qualitative time as a way to express a new present in some one else's past.

-

Temporal Design could thereforeinvolve:•Identifying dominant narratives, including the forces and infrastructures that sustain them or which they help to support;•Challenging these narratives, e.g. by revealing more nuanced expressions of time;•Drawing attention to alternative temporalities, their dynamics and significance;•Exposing networks of temporalities, so as to illustrate multiplicity and variety.The approach would bring several benefits:•Acknowledging that slow and fast rhythms co-occur and are often interdependent would challenge the assumption of universal acceleration,•Acknowledging that the times of some are more invested in than others, would enable challenges to temporal inequalities.•Acknowledging that the natural world has multiple rhythms would change the assumption that ittherefore provides a stable background for human-made ‘progress’(McKibben, 2008

Highlighting this section to return to it later with more concrete application to sociotemporal representations/expressions in crises and response to crises.

-

LARISSA PSCHETZ, MICHELLE BASTIAN, CHRIS SPEED 6With this in mind we propose Temporal Design as a shift within design towards a pluralist perspectiveon time. Temporal Design attempts to identify and challenge expressions of dominant narratives of time, as it recognises that everyday rhythms are composed of multiple temporalities, whichare defined by both direct and indirect factors. It also seeks to empower alternative notions that are neglected by these narratives. It suggests that designers should start looking at time as something that emerges in relation to a complexity of cultural, social, economicand political forces.Temporal designers wouldtherefore observe time in the social context, investigating beyond narratives of a universal time and linear progression, and beyond simple dichotomies of fast and slow. This is not to simply negate dominant notions but acknowledging that they co-exist with several other expressions in all aspects of life. There is a multiplicity of temporalities latent in the world. Designers can help to create tools that disclose them, also revealing the intricacies of temporal relationships and negotiations that take place across individuals, groups, and institutions. They would then consider a network of times that accommodates the multiplicity of temporalities in the everyday, the natural world, and in intersections between these re

Further description of the idea around Temporal Design. But still lacks clarity about what "multiple temporalities" are and how they manifest in social coordination.

Note to self: Use the template margins to offer concrete examples in my paper. The lack of specificity is frustrating and will surely draw the wrath of the reviewers.

-

Despite a clear social motivation, the alternative approaches to time in design described above have been constrained by dominant narratives of time. Further they have often only considered time in terms of pace, direction and flow rather than the more complex ways that it is involved in social life (e.g. Gre

Look up Greenhouse 1996 paper.

-

Thus in developing a theoretical framework which could support an understanding of time as multiple, heterogeneous and deeply entangled within various social formations (which may be discrete or overlapping), work in the social sciences, particularly anthropology and sociology, has proven to be more useful. Such approaches enable us to ask different questions about what time is and how it works. Rather than seeing time as a flow between past, present and future (whether this be linear or nonlinear), it becomes possible to ask how time operates as a system for social collaboration (Sorokin and Merton 1937), how it legitimates some and ‘manages’ others (Greenhouse 1996), or how it works within systems of exclusion (Fabian 1983). We thus move from time as flow to time as s

Describes how time bridges into the concept of social coordination.

Look up the Sorokin and Merton (1937). Greenhouse (1996) and Fabian (1983) papers to get a better handle on how "social coordination" is defined.

-

tries (Prado 2013). Here again, instead of looking at the present as a heterogeneous context, the present isconsidered as uniform and following a linear trajectory toward

This is an important caveat for the study of sociotemporality in humanitarian crises. Need to stay grounded in the present and how even some immediate, incremental steps toward improving the representation of time in the data and in the data gathering process can be serve the larger, future goals of attaining real-time situational awareness.

-

(Dunne, 1999). The call has influenced movements such as Critical Design (Dunne and Raby, 2001), Design Fictions (Bleecker, 2009) and Design for Debate (Dunne and Raby, 200

Unclear as to how these movements differ:

Critical Design Design Fiction Design for Debate

-

Design has also taken a critical approach to time in its attempt to anticipate the impacts of present actions in the future, particularly those concerning the introduction of new technologies. This attitude may be generally identified in particular design projects but is most evident in speculative design movements such as Design Fictions, Critical Design and Design for Debate.Since design is often focused on yet-to-exist interventions in a given context, it is often said to be invariably future-oriented (e.g. in Dunne & Rab

Look up Dunne & Raby's 2013 paper. This could be helpful to frame/cite in the virtual participatory design study.

-

evices. Similarly, Phoebe Sengers (2011) reflects on the way slower attitudes could be promoted by ‘‘making fewer choices, accessing less information, making productivity less central, keeping our lives less under formal control’’; she further considers how this attitude could be reflected in the design of communication technologies. Instead of reinforcing dichotomies, Fullerton (2010) and Sengers (2011) draw attention to practices that emphasise alternative expressions

Look up Sengers 2011 paper on ICT design.

What are the alternative expressions of time she references?

-

The association of alternative approaches to time with a rejection of technology reinforces dichotomies that do not reflect the way people relate to artefacts and systems (Wajcman 2015). As a result, these proposals not only risk being interpreted as nostalgic or backward looking, but also leave little space for integrating more complex accounts of time (particularly those arising in the social sciences) or for discussing more nuanced rhythms, as well as more complex forces and consequences related to temporal decisions. As a result, instead of challenging dominant accounts of time, these proposals arguably reinforce the overarching narrative of universalised acceler

Argument that slow technology is not anti-technology but should encourage different perspective on how people relate to artifacts and systems via time, rhythms, and other forces that help drive temporal decisions.

-

gs done. Accepting an invitation for reflection inherent in the design means on the other hand that time willappear, i.e. we open up for time presence” (Hallnas & Redstrom 2001). A slow technology would not disappear, but would make its

The idea of making time more present/more felt is counter-intuitive to how time is experienced in crisis response as urgent, as a need for effiicency, as an intense flow (Csikszentmihalyi) that disappears.

-

In Slow Technology, Hallnas & Redstrom (2001) advance the need for a form of design that emphasises reflection, the amplification of environments, and the use of technologies that a) amplify the presence of time; b) stretch time and extend processes; and c) reveal an expression of presenttime as slow-paced. Important here is the concept of “time presence”: “when we use a thing as an efficient tool, time disappears, i.e. we get things done. Accepting an invitation for reflection inherent in the design means on the other hand that time willappear, i.e. we open up for time presence” (Hallnas & Redstrom 2001). A slow technology would not disappear, but would make its

Definition of "slow technology" and its purpose to make time more present for the user.

-

Argument for the need for Temporal Design and how it could lead to broader notions/ideas/solutions of time's role in social coordination.

Tags

- critical design

- sociotemporality

- qualitative time representation

- speculative

- temporal expressions

- flow

- design fiction

- temporal design

- ICT

- school time

- rhythms

- horizon

- situated time

- time presence

- design implication

- present as past

- slow technology

- Time Machine Project

- future

- social coordination

- timescape

- trajectory

Annotators

URL

-

- May 2018

-

emlis.pair.com emlis.pair.com

-

The information contained in the information system is notsufficient in itself; the temporal context within which it can be placed,organized according to the trajectory, helps makes sense of it.

Likewise, in SBTF data collection. Temporal contexts are crucial but often not captured consistently or at all.

What are the temporal contexts in crisis situations that could/should be collected so that it doesn't lack meaning or is misinterpreted later?

-