Uh, yeah, I'm in a few groups. There's a couple of the crypto focused, uh, the also have been just, I wouldn't say [inaudible], but have put more emphasis on, you know, since we're technical traders, there's a reason not to take advantage of, uh, the market opportunities and traditional as they pop up. So we've been focused mainly on just very few inverse etfs to short the s&p to short some major Chinese stocks, um, doing some stuff with, uh, oil, gas. And then there's some groups that I'm in that are specifically focused on just traditional, uh, that are broken up or categorized by what they're trading.

- Jan 2019

-

www.at-the-intersection.com www.at-the-intersection.com

-

-

static1.squarespace.com static1.squarespace.com

-

multiple and collective

Knowledge is social.

-

-

static1.squarespace.com static1.squarespace.com

-

“It seems like everything used to be something else, yes?”

Everything used to be something else, just like everything that is to come will have been something else first. This is one of the biggest proponents to knowledge being a social act. Every idea you have was sparked by something that you observed outside of yourself.

-

-

www.weibo.com www.weibo.com

-

#快如科技2019发布会# 聊天给钱、看新闻给钱、买东西给钱、玩游戏给钱……在聊天宝,几乎干啥都给钱。

<big>评:</big><br/><br/> 这一次,罗永浩的发布会上有一张幻灯片如是写道: <br/><br/> 「为什么 Facebook 挣到的钱大部分进了马克扎克伯格的口袋?」 <br/><br/> 对于上述设问,想必罗永浩早已得出自己的答案。但从此次推出的聊天软件「聊天宝」来看,他似乎一直在刻意强调「激励机制」的作用,而这点也被许多内容公链方拿来借势营销了一把。「拿出部分利润来回报用户参与」看似要革老平台的命,实则只是刺激流量的运营手段,同那些鼓励用户主动观看广告以换取游戏道具的手游并无本质差异,而这与区块链社交的设计蓝图相差甚远——社交产品最重要的激励凭证不是金钱,而是人际关系,更何况你我都同处在「『关系』等同于金钱」的社会大环境里。当我们谈论区块链社交产品时,我们应首先关注新秩序下人际关系网的重塑,其次才是利益的重新分配。 <br/><br/> 或许可以说,驾驭产品,就是驾驭那些随时随地能满足的欲望,包括匹配得很精准的欲望,但欲望并不等同于需求,亦或是利益。当产品经理试图深刻地理解人性时,我们就应当往更深处去进化自己的人性。经理可以钻研产品之道,但我们要当魔。

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

foucault.info foucault.info

-

Seneca stresses the point: the practice of the self involves reading, for one could not draw everything from ones own stock or arm oneself by oneself with the principles of reason that are indispensable for self-conduct: guide or example, the help of others is necessary

This made me think of David Bartholomae's piece, "Inventing the University." One cannot just know things and be able to write about them unless they are introduced to by some outside force. And, one cannot attempt to find new meaning unless you have prior meaning you can debunk or build upon. https://wac.colostate.edu/jbw/v5n1/bartholomae.pdf

-

-

www.techdirt.com www.techdirt.com

-

Do we want technology to keep giving more people a voice, or will traditional gatekeepers control what ideas can be expressed?

Part of the unstated problem here is that Facebook has supplanted the "traditional gatekeepers" and their black box feed algorithm is now the gatekeeper which decides what people in the network either see or don't see. Things that crazy people used to decry to a non-listening crowd in the town commons are now blasted from the rooftops, spread far and wide by Facebook's algorithm, and can potentially say major elections.

I hope they talk about this.

-

-

indiedigitalmedia.com indiedigitalmedia.com

-

“I’m always genuinely happy to interact with listeners,” he said, “and since some prefer social media, I use it. But my (thus far only modestly effective) strategy has been to try and produce enduring content and let it speak for itself, rather than posting ephemera on Facebook and Twitter at regular intervals.”

I love his use of the word "ephemera" in relation to social media, particularly as he references his podcast about ancient history.

-

-

-

This distinction enlightens the reading of thegrowing social media and mass emergency lit-erature for three reasons. First, without it, thisnew literature risks undoing decades of work bysocial scientists who have dismantled the mythsof disaster, with a dominant discourse thatincludes panic and unlawful behavior by victims.But in disasters arising from natural hazards, weknow such behaviors are not typical. Massemergencies arising from criminal behavior canhave a much wider range of collective behaviorbecause the source of the hazard is unknown,unpredictable and perhaps more imminentlydangerous

Palen and Hughes raise concern about boundaries and classification in mass emergency research. They define crisis as an overarching term that incorrectly generalizes sociobehavioral phenomena during natural and criminal events.

-

Misinforma-tion arising from natural hazards or exogenousevents might be greater in kind, but less inimpact, with fewer in-common readers as it tra-verses a network that can move a little slowerthan it might in criminal mass emergency events.Because the problem-solving tends to be morediffuse in exogenous events, the same messagemight not reach enough people; in other words,the misinformation might also be thinly diffused.Misinformation in such events is more likely toage out, or not be relevant to enough locations topose a big threat—in other words, all informationin thefirst place is less likely to be categoricallycorrect or incorrect, and as such, it is hard tofindas much value in pursuing the threat of misin-formation in such situations.

Not sure I entriely agree with this argument that misinformation in natural disaster/exogenous events.

Mis/Dis-information definitely matters for those affected. (see Neal, 1997 and Phillips work on phases of response for minority groups).

What about misinformation campaigns during mass migration or other politically-tinged humanitarian crises where the exogenous factor (long-standing war, religious conflict/persecution, colonialism, etc.) is far removed from the immediate crisis? (Think 2015 migration crisis in Europe, Rohingya genocide in Myanmar implications for Bangaldesh).

Is there a middle ground between endogenous and exogenous hazards?

-

Wefindendogeneityandexogeneityof haz-ards to be a meaningful distinction in socialmedia in mass emergencies research, one thatreadily clarifies for a range of researchers andreaders who are outside the social science disci-pline. Just as events that arise from exogenousand endogenous hazards differently impact legal,political, health, and other societal systems, so dothey differently impact social media behavior.8With exogenous events, the culprit is beyondreach, and unstoppable. With endogenous agents,the suspect lies within. Therefore, organizingfeatures of the communication are distinctlydifferent, because the source(s) of the problem(s),the nature of their solutions,and the ability forthe perception of the collective control of theoutcomeare different. Online participation focu-ses on in-common salient problems when theyare present; when the problems are lessin-common and must be addressed in parallel, thecrowd organizes in many smaller groupings and,often endogeneity and exogeneity of hazardspredicts this (Palen & Anderson,2016).

Describes differences in social media response between 2012 Hurricane Sandy (exogenous) and 2013 Boston Bombing (endogenous) mass emergencies.

-

We make this point because we worrythat the very idea of“social media”flattens themany meanings of“crisis”and“emergency”forwhich social sciencefields have worked to pro-vide insight. For example, because Twitter orFacebook are available for use in any kind ofcrises, it is easy to make these applications thesalient concern, and ask“Is Twitter or Facebookbetter in emergency response?,”rather thanquestion how the very nature of emergencyresponse might beg for different forms of infor-mation seeking and reporting. We refer to thisflattening of communication medium and hazardas thesocial media and crisis confound.

Definition of social media and crisis confound

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

Our extensions also have implications for theories ontrust.

Bookmarked section for later consideration of proposal studies on how time interacts with trust in time- and safety-critical social coordination.

-

Therefore, training should focus on learning how toquickly recognize volunteers’ volition in participating inan emergent group, the tasks they might engage in, andthe support they might need to carry out those tasks.Such training could also help people to recognize thebenefits and dangers of generalized trust. It could alsohelp people to quickly evolve a coordination mecha-nism that does not rely on what people know, but oncompiling and communicating a narrative of the actionsthat volunteers take, so that others are able to assess forthemselves what actions they could take to help.

Majchrzak et al continue to suggest that emergent response training could reconceptualize a new role for emergency management professionals, aside from the default coordination/management. Further, they suggest that citizens could be trained to participate.

-

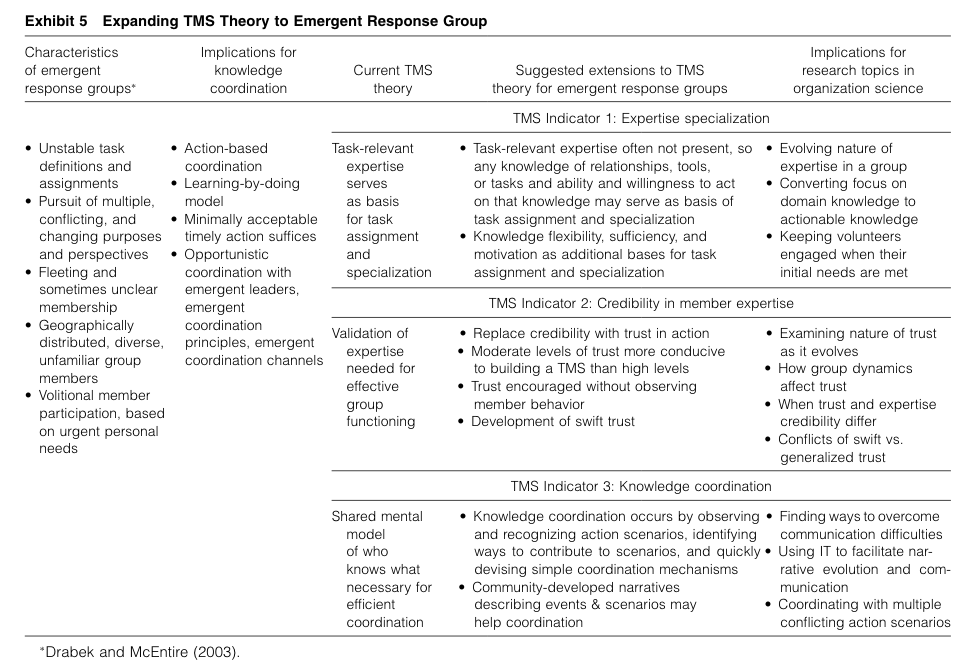

ur examination suggests that by expandingthe context in which TMS theory is applied to includeemergent response groups, insights can be gained intotheir internal dynamics. The three indicators of the levelof development of a TMS provide a useful frameworkfor organizing these insights in the exhibit.

-

The urgency of time may make it too onerous forthe extra effort of articulating actions as they are beingperformed, yet most emergency response requires somecommunication.

Interaction of time (tempo/pace) and breakdowns in articulation work.

-

Explicitly articulated narratives mayalso make clearer that multiple sequences of actions maybe occurring simultaneously, thus resolving role conflictsby allowing multiple ways to accomplish a task

Evokes Schmidt and Bannon's articulation work in CSCW.

-

Emergent response groups may also use a mechanismof creating a community narrative (Boland and Tenkasi1995), which is a running narrative of the actions takenand not taken, the decisions made, and the theories inuse. Narratives do not represent a single shared under-standing of a domain; rather they represent the mul-tiplicity of events and actions a community is taking,as members are taking them. Narratives may be articu-lated explicitly or understood implicitly.

SBTF after-action report, as an example. But who is the audience for this narrative?

-

Whenemergent response groups first come together, membersare likely not to ask one another about who knows what;instead, they are likely to ask about what is knownabout the situation and about the actions taken thus far(Dyer and Shafer 2003, Hale et al. 2005). The cogni-tive structure that they develop for the group centersnot around people, but on action-based scenarios thateither have been or might be carried out. These scenariosinclude decisions, actions, knowledge, events, and feed-back (Vera and Crossan 2005).

Suggested extensions for TMS theory:

"1. Tailor the Role of Expertise"

"2. "Replacing Credibility in Expertise with Trust Through Action"

"3. "Coordinating Knowledge Processes Without a Shared Metastructure"

-

On the surface, the lack of sta-ble membership suggests that a shared mental modelmay not be viable or even desired in emergent responsegroups. Time may be too precious to seek consensus onevents and actions, and agreements may make the groupless flexible to accommodate to changing inputs.

Evokes pluritemporal concerns about tempo, pace and synchronization.

-

hus, we believe challenges occur in all three indica-tors of the level of development of a TMS—expertisespecialization, credibility, and expertise coordination—requiring a need to consider extending theorizing abouteach indicator for emergent response groups.

Ways to extend TMS to emergent groups:

"1. Reconceptualize the Role of Expertise Specialization as a Basis for Task Assignment"

"2. Assessing Credibility in Emergent Response Groups"

"3. Expertise Coordination in Emergent Response Groups"

These extensions evoke boundary objects and invisibility

-

Moreland and Argote(2003) suggest that the dynamic conditions under whichthese groups form and work together are likely to havenegative effects on the development of transactive mem-ory.

Are there workflow or technology breakdowns that could help ameliorate the negative effects?

-

Research on TMS has identified three indicators of thelevel of development of a TMS (Lewis 2003, Morelandand Argote 2003):1.Memory (or expertise) specialization:the tendencyfor groups to delegate responsibility and to specialize indifferent aspects of the task;2.Credibility:beliefs about the reliability of mem-bers’ expertise; and3.Task (or expertise) coordination:the ability of teammembers to coordinate their work efficiently based ontheir knowledge of who knows what in the group.The greater the presence of each indicator, the more de-veloped the TMS and the more valuable the TMS is forefficiently coordinating the actions of group members.

Three indicators of the level of sophistication of the system:

• Memory specialization (think trauma/hospital care CSCW studies)

• Credibility

• Task coordination

-

A TMS can be thoughtof as a network of interconnected individual memorysystems and the transfer of knowledge among them(Wegner 1995). Individuals who are part of a TMSassume responsibility for different knowledge domains,and rely on one another to access each other’s expertiseacross domains. Expertise is defined in the TMS litera-ture to broadly include the know-what, know-how, andknow-why of a knowledge domain (Quinn et al. 1996),what Blackler (1995) refers to as embodied competen-cies. Expertise specialization, then, reduces the cognitiveload of each individual and the amount of redundantknowledge in the group, while collectively providingthe dyad or group access to a larger pool of knowl-edge. What makes transactive memory transactive arethe communications (called transactions) among individ-uals that make possible the codifying, storing, retrieving,and updating of information from individual memorysystems. For transactive memory to function effectively,individuals must have a shared conceptualization of whoknows what in the group.

Majchrzak et al describe how TMS is oeprationalized as a network.

-

TMS theory, a theoryof group-level cognition, explains how people in collec-tives learn, store, use, and coordinate their knowledge toaccomplish individual, group, and organizational goals.It is a theory about how people in relationships, groups,and organizations learn who knows what, and use thatknowledge to decide who will do what, resulting in moreefficient and effective individual and collective perfor-mance.

Definition of transactive memory systems theory -- used in org studies to understand how knowledge is coordinated among groups.

-

The urgency of the situation meansthat the objective of coordination is to achieve minimallyacceptable and timely action, even when more effec-tive responses may be feasible—but would take longerand use more resources.

temporal issues related to emergent response: pace and timeliness

-

hese characteristics require thatemergent response groups adopt specific approaches forknowledge coordination. One such approach commonlydocumented in studies of such groups is their use ofa learn-by-doing (versus decision making) action-basedmodel of coordinated problem solving, in which sensemaking and improvisation are the norm rather than theexception

Evokes LPP, sensemaking, and improvised coordination.

-

isaster researchers havedefinedemergent response groupsas collectives of indi-viduals who use nonroutine resources and activities toapply to nonroutine domains and tasks, using nonroutineorganizational arrangements (Bigley and Roberts 2001,Drabek et al. 1981, Drabek 1986, Drabek and McEntire2003, Kreps 1984, Tierney et al. 2001).

Definition of emergent response groups

-

Disasters have wideimplications for expertise coordination because the pre-conditions known to facilitate expertise coordination arelimited or nonexistent in disaster response. Such precon-ditions include but are not limited to, a shared goal; aclear reward structure; known group membership, exper-tise, and skills to accomplish the task; and time to sharewho knows what.

Implications for org studies research.

At least as of 2007 (publication date), the internal dynamics of emergent orgs were still relatively unknown.

The dynamics of professional-emergent disaster response is under-studied.

-

Although the con-ventional indicators of efficient coordination—expertisespecialization, credibility in expertise, and coordinationof expertise—are relevant in disaster response, disasterspresent a unique operational environment. Disasters are“events, observable in time and space, in which societiesor their subunits (e.g., communities, regions) incur phys-ical damages and losses and/or disruption of their routine

"Disasters represent a unique operational environment."

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

Experimentation, the third affordance, refers to theuse of technology to encourage participants to try outnovel ideas.

Definition of experimentation.

Describes the use of comment/feedback boxes, ratings, polls, etc. to generate ideas for new coordination workflows, design ideas, workarounds, etc.

-

Recombinability refers to forms of technology-enabled action where individual contributors build oneach others’ contributions.

Definition of recombinability.

Cites Lessig in describing recombinability "as both a technology design issue and a community governance principle" for reusing/remixing/recombining knowledge

-

Reviewability refers to the enactment of technology-enabled new forms of working in which participantsare better able to view and manage the content offront and back narratives over time (West and Lakhani2008). By allowing participants to easily and collab-oratively review a range of ideas, technology-affordedreviewability helps the community respond to tensionsin disembodied ideas, because the reviews can provideimportant contextual information for building on others’ideas.

Definition of reviewability.

Faraj et al offer the example of Wikipedia edit log to track changes.

-

Technology platforms used by OCs can providea number of affordances for knowledge collabora-tion, three of which we mention here: reviewability,recombinability, and experimentation. These affordancesevolve as new participants provide new ways to use thetechnologies, new social norms are developed around thetechnology affordances, and new needs for fresh affor-dances are identified.

Ways that technology affordances can influence/motivate change in social coordination practices.

-

Given the fluid nature of OCsand their rapidly evolving technology platforms, and inline with calls to avoid dualistic thinking about tech-nology (Leonardi and Barley 2008, Markus and Silver2008, Orlikowski and Scott 2008), we suggest technol-ogy affordance as a generative response, one that viewstechnology, action, and roles as emergent, inseparable,and coevolving. Technology affordances offer a relationalperspective on human action, where neither the technol-ogy nor the actor is dominant in the sense that the tech-nology does not define what is possible for the actor todo, nor is the actor free from the limitations of the tech-nological environment. Instead, possibilities for actionemerge from the reciprocal interaction between actor andartifact (Gibson 1979, Zammuto et al. 2007). Thus, anaffordance perspective focuses on the organizing actionsthat are afforded by technology artifacts.

Interesting perspective on how technology affordances are a generative response to coordination tensions.

-

third response to manage tensions is to promoteknowledge collaboration by enacting dynamic bound-aries. In social sciences, although boundaries divide anddisintegrate collectives, they also coordinate and inte-grate social action (Bowker and Star 1999, Lamont andMolnár 2002). Fluidity brings the need for flexible andpermeable boundaries, but it is not only the propertiesof the boundaries but also their dynamicity that helpmanage tensions.

Cites Bowker and Star

Good examples of how boundaries co-evolve and take on new meanings follow this paragraph.

-

We have observed in OCs that no single narrative isable to keep participants informed about the current stateof the OC with respect to each tension. These commu-nities seem to develop two different types of narratives.Borrowing from Goffman (1959), we label the two nar-ratives the “front” and the “back” narratives.

Cites Goffman and the performative vs invisible aspects of social coordination work.

-

Based on our collective research on to date, we haveidentified that as tensions ebb and flow, OCs use (or,more precisely, participants engage in) any of the fourtypes of responses that seem to help the OC be gen-erative. The first generative response is labeledEngen-dering Roles in the Moment. In this response, membersenact specific roles that help turn the potentially negativeconsequences of a tension into positive consequences.The second generative response is labeledChannelingParticipation. In this response, members create a nar-rative that helps keep fluid participants informed ofthe state of the knowledge, with this narrative havinga necessary duality between a front narrative for gen-eral public consumption and a back narrative to airthe differences and emotions created by the tensions.The third generative response is labeledDynamicallyChanging Boundaries. In this response, OCs changetheir boundaries in ways that discourage or encouragecertain resources into and out of the communities at cer-tain times, depending on the nature of the tension. Thefourth generative response is labeledEvolving Technol-ogy Affordances. In this response, OCs iteratively evolvetheir technologies in use in ways that are embedded by,and become embedded into, iteratively enhanced socialnorms. These iterations help the OC to socially and tech-nically automate responses to tensions so that the com-munity does not unravel.

Productive responses to experienced tensions.

Evokes boundary objects (dynamically changing boundaries) and design affordances/heuristics (evolving technology affordances)

-

Tension 5: Positive and Negative Consequences ofTemporary ConvergenceThe classic models of knowledge collaboration in groupsgive particular weight to the need for convergence. Con-vergence around a single goal, direction, criterion, pro-cess, or solution helps counterbalance the forces ofdivergence, allowing diverse ideas to be framed, ana-lyzed, and coalesced into a single solution (Couger 1996,Isaksen and Treffinger 1985, Osborn 1953, Woodmanet al. 1993). In fluid OCs, convergence is still likelyto exist during knowledge collaboration, but the conver-gence is likely to be temporary and incomplete, oftenimplicit, and is situated among subsets of actors in thecommunity rather than the entire community.

Positive consequences: The temporary nature can advance creative uses of the knowledge without hewing to structures, norms or histories of online collaboration.

Negative consequences: Lack of P2P feedback may lead to withdrawal from the group. Pace of knowledge building can be slow and frustrating due to temporary, fleeting convergence dynamics of the group.

-

ension 2: Positive and Negative Consequencesof TimeA second tension is between the positive and negativeconsequences of the time that people spend contribut-ing to the OC. Knowledge collaboration requires thatindividuals spend time contributing to the OC’s virtualworkspace (Fleming and Waguespack 2007, Lakhani andvon Hippel 2003, Rafaeli and Ariel 2008). Time has apositive consequence for knowledge collaboration. Themore time people spend evolving others’ contributedideas and responding to others’ comments on thoseideas, the more the ideas can evolve

Positive consequences: Attention helps to advance the reuse/remix/recombination of knowledge

Negative consequences: "Old-timers" crowd out newcomers

Tension can lead to "unpredictable fluctuations in the collaborative process" such as labor shortages, lack of fresh ideas, in-balance between positive/negative consequences that catalyzes healthy fluidity

Need to consider other possibilities for time/temporal consequences. These examples seem lacking.

-

We argue that it is the fluidity, the tensions that flu-idity creates, and the dynamics in how the OC respondsto these tensions that make knowledge collaboration inOCs fundamentally different from knowledge collabora-tion in teams or other traditional organization structures.

Faraj et al identify 5 tensions that have received little attention in the literature (doesn't mean these are the only tensions):

passion, time, socially ambiguous identities, social disembodiment of ideas, and temporary convergence.

-

As fluctuations in resource endowments arise overtime because of the fluidity in the OC, these fluctua-tions in resources create fluctuations in tensions, makingsimple structural tactics for managing tensions such ascross-functional teams or divergent opinions (Sheremata2000) inadequate for fostering knowledge collaboration.As complex as these tension fluctuations are for the com-munity, it is precisely these tensions that provide thecatalyst for knowledge collaboration. Communities thatthen respond to these tensions generatively (rather thanin restrictive ways) will be able to realize this potential.Thus, it is not the simple presence of resources that fos-ter knowledge collaboration, but rather the presence ofongoing dynamic tensions within the OC that spur thecollaboration. We describe these tensions in the follow-ing section

Tension as a catalyst for knowledge work/collaboration

-

Fluidity requires us to look at the dynamics—i.e., thecontinuous and rapid changes in resources—rather thanthe presence or the structural form of the resources.Resources may flow from outside the OC (e.g., pas-sion) or be internally generated (e.g., convergence), sub-sequently influencing and influenced by action (Feldman2004). Resources come with the baggage of having bothpositive and negative consequences for knowledge col-laboration, creating a tension within the community inhow to manage the positive and negative consequencesin a manner similar to the one faced by ambidextrousorganizations (O’Reilly and Tushman 2004).

Fluidity vs material resources

-

However, failure to examine the critical roleof even the inactive participants in the functioning of thecommunity is to ignore that passive (and invisible) par-ticipation may be a step toward greater participation, aswhen individuals use passivity as a way to learn aboutthe collective in a form of peripheral legitimate partici-pation (Lave and Wenger 1991, Yeow et al. 2006).

Evokes LPP

-

Fluidity recognizes the highly flexible or permeableboundaries of OCs, where it is hard to figure out whois in the community and who is outside (Preece et al.2004) at any point in time, let alone over time. Theyare adaptive in that they change as the attention, actions,and interests of the collective of participants change overtime. Many individuals in an OC are at various stagesof exit and entry that change fluidly over time.

Evokes boundary objects and boundary infrastructures.

-

We argue that fluid-ity is a fundamental characteristic of OCs that makesknowledge collaboration in such settings possible. Assimply depicted in Figure 1, we envision OCs as fluidorganizational objects that are simultaneously morphingand yet retaining a recognizable shape (de Laet and Mol2000, Law 2002, Mol and Law 1994).

Definition of fluidity: "Fluid OCs are ones where boundaries, norms, participants, artifacts, interactions, and foci continually change over time..."

Faraj et al argue that OCs extend the definition of fluid objects in the existing literature.

-

a growing consensus on factors that moti-vate people to make contributions to these communities,including motivational factors based on self-interest (e.g.,Lakhani and von Hippel 2003, Lerner and Tirole 2002,von Hippel and von Krogh 2003), identity (Bagozzi andDholakia 2006, Blanchard and Markus 2004, Ma andAgarwal 2007, Ren et al. 2007, Stewart and Gosain2006), social capital (Nambisan and Baron 2010; Waskoand Faraj 2000, 2005; Wasko et al. 2009), and socialexchange (Faraj and Johnson 2011).

Motivations include: self-interest, identity, social capital, and social exchange, per org studies researchers.

Strange that Benkler, Kittur, Kraut and others' work is not cited here.

-

For instance, knowledge collaboration in OCscan occur without the structural mechanisms tradition-ally associated with knowledge collaboration in orga-nizational teams: stable membership, convergence afterdivergence, repeated people-to-people interactions, goal-sharing, and feelings of interdependence among groupmembers (Boland et al. 1994, Carlile 2002, Dougherty1992, Schrage 1995, Tsoukas 2009).

Differences between offline and online knowledge work

Online communities operate with fewer constraints from "social conventions, ownership, and hierarchies." Further, the ability to remix/reuse/recombine information into new, innovative forms of knowledge are easier to generate through collaborative technologies and ICT.

-

Knowledge collaboration is defined broadly as thesharing, transfer, accumulation, transformation, andcocreation of knowledge. In an OC, knowledge collab-oration involves individual acts of offering knowledgeto others as well as adding to, recombining, modify-ing, and integrating knowledge that others have con-tributed. Knowledge collaboration is a critical elementof the sustainability of OCs as individuals share andcombine their knowledge in ways that benefit them per-sonally, while contributing to the community’s greaterworth (Blanchard and Markus 2004, Jeppesen andFredericksen 2006, Murray and O’Mahoney 2007, vonHippel and von Krogh 2006, Wasko and Faraj 2000).

Definition of knowledge work

-

Online communities (OCs) are open collectives of dis-persed individuals with members who are not necessarilyknown or identifiable and who share common inter-ests, and these communities attend to both their indi-vidual and their collective welfare (Sproull and Arriaga2007).

Definition of online communities

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

The situated and emergent nature of coordinationdoes not imply that practices are completely uniqueand novel. On the one hand, they vary accordingto the logic of the situation and the actors present.On the other hand, as seen in our categorizationof dialogic coordination, they follow a recognizablelogic and are only partially improvised. This tensionbetween familiarity and uniqueness of response is atthe core of a practice view of work (Orlikowski 2002).

This is an important and relevant point for SBTF/DHN work. Each activation is situated and emergent but there are similarities -- even though the workflows tend to change for reasons unknown.

Cites Orlikowski

-

Recently, Brown and Duguid (2001, p. 208) sug-gested that coordination of organizational knowledgeis likely to be more challenging than coordination ofroutine work, principally because the “elements to becoordinated are not just individuals but communitiesand the practices they foster.” As we found in ourinvestigation of coordination at the boundary, signif-icant epistemic differences exist and must be recog-nized. As the dialogic practices enacted in responseto problematic trajectories show, the epistemic dif-ferences reflect different perspectives or prioritiesand cannot be bridged through better knowledge

Need to think more about how subgroups in SBTF (Core Team/Coords, GIS, locals/diaspora, experienced vols, new vols, etc.) act as communities of practice. How does this influence sensemaking, epistemic decisions, synchronization, contention, negotiation around boundaries, etc.?

-

nature point to the limitations of a structuralist viewof coordination. In the same way that an organi-zational routine may unfold differently each timebecause it cannot be fully specified (Feldman andPentland 2003), coordination will vary each time.Independent of embraced rules and programs, therewill always be an element of bricolage reflecting thenecessity of patching together working solutions withthe knowledge and resources at hand (Weick 1993).Actors and the generative schemes that propel theiractions under pressure make up an important com-ponent of coordination’s modus operandi (Bourdieu1990, Emirbayer and Mische 1998).

Evokes the improvisation of synchronization efforts found in coordination of knowledge work in a pluritemporal setting

-

These practices are highly situated, emer-gent, and contextualized and thus cannot be prespec-ified the way traditional coordination mechanismscan be. Thus, recent efforts based on an information-processing view to develop typologies of coordina-tion mechanisms (e.g., Malone et al. 1999) may be tooformal to allow organizations to mount an effectiveresponse to events characterized by urgency, novelty,surprise, and different interpretations.

More design challenges

-

Our findings also point to a broader divide in coor-dination research. Much of the power of traditionalcoordination models resides in their information-processing basis and their focus on the design issuessurrounding work unit differentiation and integra-tion. This design-centric view with its emphasis onrules,structures,andmodalitiesofcoordinationislessuseful for studying knowledge work.

The high-tempo, non-routine, highly situated knowledge work of SBTF definitely falls into this category. Design systems/workarounds is challenging.

-

Boundarywork requires the ability to see perspectives devel-oped by people immersed in a different commu-nity of knowing (Boland and Tenkasi 1995, Star andGriesemer 1989). Often, particular disciplinary focilead to differences in opinion regarding what stepsto take next in treating the patient.

Differences in boundary work can lead to contentiousness.

-

The termdialogic—as opposed to monologic—recognizes dif-ferences and emphasizes the existence of epistemicboundaries, different understandings of events, andthe existence of boundary objects (e.g., the diagnosisor the treatment plan). A dialogic approach to coordi-nation is the recognition that action, communication,and cognition are essentially relational and highlysituated. We use the concept of trajectory (Bourdieu1990, Strauss 1993) to recognize that treatment pro-gressions are not always linear or positive.

Cites Star (boundary objects) and Strauss, Bourdieu (trajectory)

-

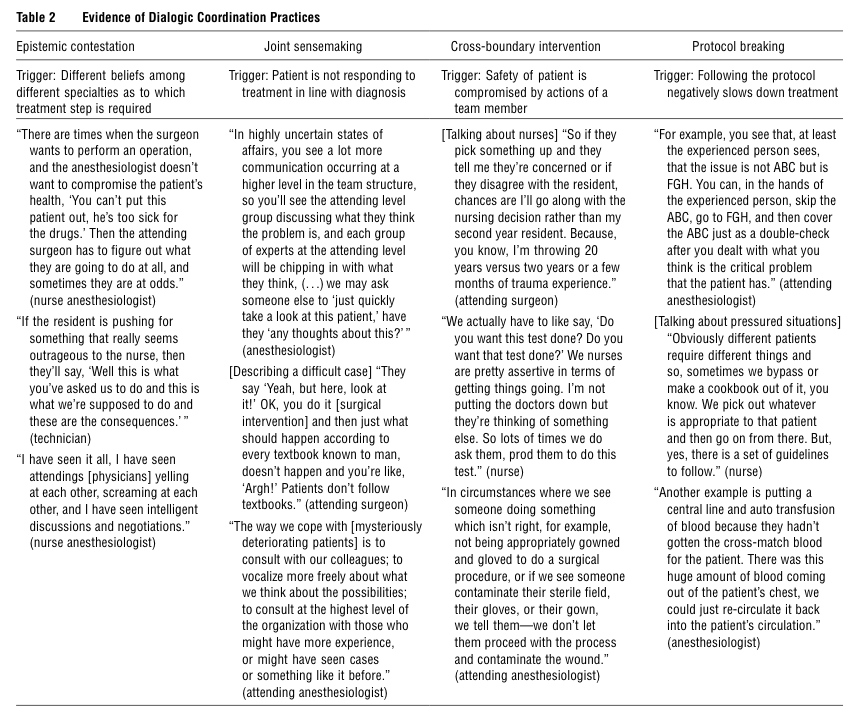

A dialogic coordination practice differs from moregeneral expertise coordination processes in that itis highly situated in the specifics of the unfoldingevent, is urgent and high-staked, and occurs at theboundary between communities of practice. Becausecognition is distributed, responsibility is shared, andepistemic differences are present, interactions can becontentious and conflict laden.

Differences between expertise and dialogic coordination processes.

-

xpertisecoordination refers to processes that manage knowl-edge and skill interdependencies

-

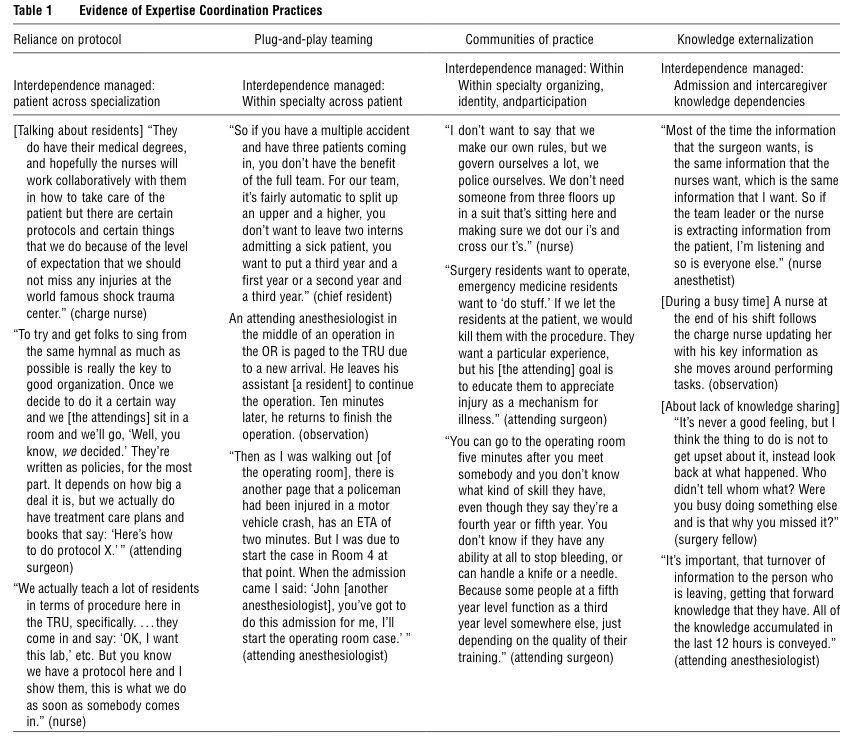

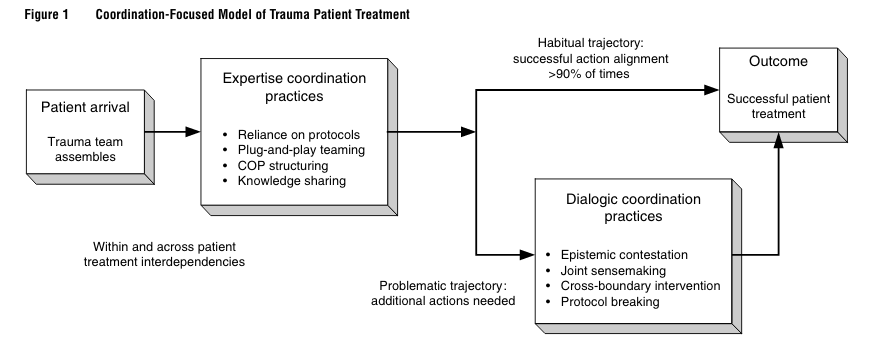

we describe two categories ofcoordination practices that ensure effective work out-comes. The first category, which we callexpertise coor-dination practices, represents processes that make itpossible to manage knowledge and skill interdepen-dencies. These processes bring about fast response,superior reconfiguration, efficient knowledge shar-ing, and expertise vetting. Second, because of therapidlyunfoldingtempooftreatmentandthestochas-tic nature of the treatment trajectory,dialogic coordina-tion practicesare used as contextually and temporallysituated responses to occasional trajectory deviation,errors, and general threats to the patient. These dia-logic coordination practices are crucial for ensuringeffective coordination but often require contentiousinteractions across communities of practice. Figure 1presents a coordination-focused model of patienttreatment and describes the circumstances underwhich dialogic coordination practices are called for.

-

We found that coordination in a trauma settingentails two specific practices.

"1. expertise coordination practices"

"2. dialogic coordination practices"

What would be the SBTF equivalent here?

-

Based on a practice view, we suggest the followingdefinition ofcoordination: a temporally unfolding andcontextualized process of input regulation and inter-action articulation to realize a collective performance.

Faraj and Xiao offer two important points: Context and trajectories "First, the definition emphasizes the temporal unfolding and contextually situated nature of work processes. It recognizes that coordinated actions are enacted within a specific context, among a specific set of actors, and following a history of previous actions and interactions that necessarily constrain future action."

"Second, following Strauss (1993), we emphasize trajectories to describe sequences of actions toward a goal with an emphasis on contingencies and interactions among actors. Trajectories differ from routines in their emphasis on progression toward a goal and attention to deviation from that goal. Routines merely emphasize sequences of steps and, thus, are difficult to specify in work situations characterized by novelty, unpredictability, and ever-changing combinations of tasks, actors, and resources. Trajectories emphasize both the unfolding of action as well as the interactions that shape it. A trajectory-centric view of coordination recognizes the stochastic aspect of unfolding events and the possibility that combinations of inputs or interactions can lead to trajectories with dreadful outcomes—the Apollo 13 “Houston, we have a problem” scenario. In such moments, coordination is more about dealing with the “situation” than about formal organizational arrangements."

-

Theprimarygoalispatientstabilizationandini-tiating atreatment trajectory—a temporally unfolding

Full quote (page break)

"The primary goal is patient stabilization and initiating a treatment trajectory—a temporally unfolding sequence of events, actions, and interactions—aimed at ensuring patient medical recovery"

Knowledge trajectory is a good description of SBTF's work product/goal

-

rauma centersare representative of organizational entities that arefaced with unpredictable environmental demands,complexsetsoftechnologies,highcoordinationloads,and the paradoxical need to achieve high reliabilitywhile maintaining efficient operations.

Also a good description of digital humanitarian work

-

We sug-gest that for environments where knowledge work isinterdisciplinary and highly contextualized, the rele-vant lens is one of practice. Practices emerge from anongoing stream of activities and are enacted throughthe contextualized actions of individuals (Orlikowski2000). These practices are driven by a practical logic,thatis,arecognitionofnoveltaskdemands,emergentsituations,andtheunpredictabilityofevolvingaction.Bourdieu (1990, p. 12) definespracticesas generativeformulas reflecting the modus operandi (manner ofworking) in contrast to the opus operatum (finishedwork).

Definition and background on practice.

Cites Bourdieu

-

In knowledge work, several related factors sug-gest the need to reconceptualize coordination.

Complex knowledge work coordination demands attention to how coordination is managed, as well as what (content) and when (temporality).

"This distinction becomes increasingly important in complex knowledge work where there is less reliance on formal structure, interdependence is changing, and work is primarily performed in teams."

Traditional theories of coordination are not entirely relevant to fast-response teams who are more flexible, less formally configured and use more improvised decision making mechanisms.

These more flexible groups also are more multi-disciplinary communities of practice with different epistemic standards, work practices, and contexts.

"Thus, because of differences in perspectives and interests, it becomes necessary to provide support for cross-boundary knowledge transformation (Carlile 2002)."

Evokes boundary objects/boundary infrastructure issues.

-

Usinga practice lens (Brown and Duguid 2001, Orlikowski2000), we suggest that in settings where work iscontextualized and nonroutine, traditional models ofcoordination are insufficient to explain coordinationas it occurs in practice. First, because expertise is dis-tributed and work highly contextualized, expertisecoordination is required to manage knowledge andskill interdependencies. Second, to avoid error andto ensure that the patient remains on a recoveringtrajectory, fast-response cross-boundary coordinationpractices are enacted. Because of the epistemic dis-tance between specialists organized in communitiesofpractice,theselattercoordinationpracticesmagnifyknowledge differences and are partly contentious.

Faraj and Xiao contend that coordination practices of fast-response organizations differ from typical groups' structures, decision-making processes and cultures.

1) Expertise is distributed 2) Coordination practices are cross-boundary 3) Knowledge differences are magnified

-

In this paper, we focus on the collective perfor-manceaspectofcoordinationandemphasizethetem-poral unfolding and situated nature of coordinativeaction. We address how knowledge work is coor-dinated in organizations where decisions must bemade rapidly and where errors can be fatal.

Summary of paper focus

-

-

wendynorris.com wendynorris.com

-

Also, with disaster research having strong theoretical ties with the study of collective behavior(Wenger 1987), and with the field of collective behavior often looking at issues related to social change {e.g., riots, social movements), another link between disasters and social change has implicitly

Neal connects concerns about disaster-driven social change and the natural desire for people to respond via some collective action impulse.

Nice segue into SBTF as collection action motivated by social change

-

Cross-cultural disaster research may also provide further insights regarding disaster phases.

Evokes feminist, critical and post-colonial theory, as well as multi- and inter-disciplinary research methods/perspectives, e.g., anthropology, etc.

These points of view may also provide insights on how disaster phases interact with wholly different notions of social time.

-

As the field of collective behavior highlights, individuals in social settings have different perceptions of reality-social settings are not homogeneous (e.g., Turner and Killian I 987).' Thus, to tap further the mutually inclusive, multidimensional and social-time aspects of disaster phases, researchers should draw upon multiple publics and their definition of disaster phases.

Neal suggests avoiding the disaster phase terminology when interviewing various stakeholders (emergency mgt, disaster-affected people, government agencies) in order to "draw upon various groups' language to describe phases" instead of the National Governors Assn phases.

-

Consid� e�g the redefinition of disaster phases based on social time may help us WJtb the broader and more important struggle of defining disaster.

What happened with this call to arms? Did Neal or others in the emergency management research community follow up?

http://ijmed.org/articles/624/download/ <-- Neal's 2013 paper on "Social Time and Disaster"

-

Consid� e�g the redefinition of disaster phases based on social time may help us WJtb the broader and more important struggle of defining disaster

Neal wrote a more recent 2013 paper discussing the topic of social time and disaster.

-

D!saster and hazard researchers have recognized the social time aspect of disasters. Dynes_ (1970) alludes to social time regarding the social consequences of a disaster. Dynes observes that social time: is important because the activities of every community vary over a period of time duri�� �e day, the week, the month, and the year. S�c� patterned acuv1nes have implications for potential damage within thecommurnty, for preventative activity within the commu�ty, for the inventory of the meaning of the disaster, for the rmm�?1ate tasks necessary within the community, and for the mobilizanon of community effort. (Dynes 1970, p. 63)

As early as 1970 (pre-Zerubavel, Adam, Nowotny, and Giddens), Dynes suggested that social time be taken into account for disaster response.

** Get this paper. What social time work did he cite?

-

The Phases Should Reflect Social Rather Than Objective Time Giddens (I 987), although not the first, makes an important theoretical distinction between social and objective time. Giddens defines clock time as the use of quantified units. Clock time represents "day-to-day" structured activities. Typically, studies refer to disaster phases with hours, days, weeks, or years. Social time, however, is contingent upon the needs or opportunities of a society.

Cites Giddens here to describe differences between social time (sturcturation) and clock time.

-

-

www.theatlantic.com www.theatlantic.com

-

The technology that favored democracy is changing, and as artificial intelligence develops, it might change further.

i would like to see arguments around this as i further read.

-

-

blog.edtechie.net blog.edtechie.net

-

What social media did was to transform discovery into a passive rather than an active process.

Nicely put observation on how social media changed the way in which we discover information.

-

- Dec 2018

-

austinkleon.com austinkleon.com

-

One must always be beware of the advice-giver’s context.

-

-

inst-fs-iad-prod.inscloudgate.net inst-fs-iad-prod.inscloudgate.net

-

One is to imagine that culture is a self-contained "super-organic" reality with forces and purposes of its own; that is, to reify it. Another is to claim that it consists in the brute pattern of behavioral events we observe in fact to occur in some identifiable community or other; that is, to reduce it.

Geertz warns about the danger of reducing or reifying culture. While this may have been a debate in anthropology in 1973 (hopefully resolved), it still seems to resonate in HCI today between the factions of technological determinism and social constructionism

-

-

inst-fs-iad-prod.inscloudgate.net inst-fs-iad-prod.inscloudgate.net

-

movements, among other things, are attempts to intervene in the public sphere through collective, coordinated action. A social movement is both a type of (counter)public itself and a claim made to a public that a wrong should be righted or a change should be made.13 Regardless of whether movements are attempt-ing to change people’s minds, a set of policies, or even a government, they strive to reach and intervene in public life, which is centered on the public sphere of their time.

a solid definition of what a movement is

-

-

scripting.com scripting.com

-

His dream is to put a live Web server with easy-to-edit pages on every person's desktop, then connect them all in a robust network that feeds off itself and informs other media.

An early statement of what would eventually become all of social media.

-

The Weblog community is basically a whole bunch of expert witnesses who increase their expertise constantly through a sort of reputation engine."

The trouble is how is this "reputation engine" built? What metrics does it include? Can it be gamed? Social media has gotten lots of this wrong and it has caused problems.

-

Man, this is a beast that's hungry all the time."

Mind you he's saying this in 2001 before the creation of more wide spread social networks.

-

-

hybridpedagogy.org hybridpedagogy.org

-

It is based on reciprocity and a level of trust that each party is actively seeking value-added information for the other.

Seems like this is a critical assumption to examine for current media literacy/misinformation discussions. As networks become very large and very flat, does this assumption of reciprocity and good faith hold? (I'm thinking, here, of people whose expertise I trust in one domain but perhaps not in another, or the fact that sometimes I'm talking to one part of my network and not really "actively seeking information" for other parts.)

-

-

www.oblomovka.com www.oblomovka.com

-

On the net, you have public, or you have secrets. The private intermediate sphere, with its careful buffering. is shattered. E-mails are forwarded verbatim. IRC transcripts, with throwaway comments, are preserved forever. You talk to your friends online, you talk to the world.

-

-

ohhelloana.blog ohhelloana.blog

-

Maybe during this Christmas break I will find the guts to do a purge but I know that it will be a "fake purge".

I've been seeing a lot about (Japanes) minimalism this past year in relation to physical goods, but hadn't considered what a minimal social media presence would look like.

-

-

ricmac.org ricmac.org

-

I adopted a ‘horses for courses’ approach to keep it in check. I used Facebook primarily to keep in touch with family and real-world friends, I used Twitter for tech discussions and networking, I used LinkedIn sparingly, and I dropped any social media that didn’t fulfill a specific function for me.

-

-

gutenberg.net.au gutenberg.net.auSanditon8

-

sir

Mr. Heywood has a point regarding resort areas. Connecting this to modern day resorts, when these things pop up, the prices of everyday things are inflated. This results in the residents of the area not being able to afford to live there and become impoverished.

-

"move in a circle"

This phrase is often used in Austen's works, referring to the particular society or selected families a person interacts with, and which usually indicates a level of social class. In Pride and Prejudice, Mrs. Gardener says she "moved in different circles" from the Darcys, and in Emma, Mrs. Elton hopes to install Miss Fairfax as a governess in a better circle than she might be able to procure on her own.

-

neither able to do or suggest anything

This might be a genuine characerization of the wife or possibly a sarcastic comment on the stereotypes of women during the time.

-

fancy themselves equal

Highlights the slight strife between "old" and "new" money. Lady Denham's words seem reminiscent of Sir Walter Elliot's disdain for those who made their fortune instead of inheriting it in Persuasion.

-

The mere trash

Many people criticized circulating libraries in the 17th and 18th centuries due to the genre they gave access to--the novel. It was thought that the novel would ruin people's minds and give them false expectations of life. Source.

-

rich people

A powerful final line concluding the chapter, as it reflect's Austen's larger criticism of "rich people" who she believes often behave with distasteful and contemptible motivations. In this instance, Austen labels rich people as "sordid."

-

seen romantically situated among wood on a high eminence at some little distance

This description of a cottage reminds me of the contrast in Austen's Sense and Sensibility between how the upper classes and the landed gentry view cottages. The upper classes view cottages in a romantic way as cute, comfy homes, however the landed gentry know that cottages result out of a neccesity brough on by an oppresive and restrictive economic system.

https://janeaustensworld.wordpress.com/tag/19th-century-cottages/

-

Links to common words/themes throughout the annotations

Tags

- poetry

- marriage plot

- geography

- northanger abbey

- plot

- pride & prejudice

- health

- tone

- Emma

- vocab

- reference

- persuasion

- predictions

- synopsis

- prose

- mansfield park

- emma

- sense & sensibility

- history

- mr parker

- austen lore

- opinion

- sir edward

- social commentary

- theme

- pride and prejudice

- lady denham

- other Austen

- sir walter elliot

- other austen

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.independent.co.uk www.independent.co.uk

-

signal-boost

another great description of the phenomenon

-

-

infojustice.org infojustice.org

-

Today, I had the privilege of speaking on a panel at the Comparative and International Education Society’s Annual Conference with representatives of two open education projects that depend on Creative Commons licenses to do their work. One is the OER publisher Siyavula, based in Cape Town, South Africa. Among other things, they publish textbooks for use in primary and secondary school in math and science. After high school students in the country protested about the conditions of their education – singling out textbook prices as a barrier to their learning – the South African government relied on the Creative Commons license used by Siyavula to print and distribute 10 million Siyavula textbooks to school children, some of whom had never had their own textbook before. The other are the related teacher education projects, TESSA, and TESS-India, which use the Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike license on teacher training materials. Created first in English, the projects and their teachers rely on the reuse rights granted by the Creative Commons license to translate and localize these training materials to make them authentic for teachers in the linguistically and culturally diverse settings of sub-Saharan Africa and India. (Both projects are linked to and supported by the Open University in the UK, http://www.open.ac.uk/, which uses Creative Commons-licensed materials as well.) If one wakes up hoping to feel that one’s work in the world is useful, then an experience like this makes it a good day.

I think contextualizing Creative Commons material as a component in global justice and thinking of fair distribution of resources and knowledge as an antidote to imperialism is a provocative concept.This blog, infojusticeorg offers perspectives on social justice and Creative Commons by many authors.

-

- Nov 2018

-

inst-fs-iad-prod.inscloudgate.net inst-fs-iad-prod.inscloudgate.net

-

Digital connectivity reshapes how movements connect, organize, and evolve during their lifespan.

-

My goal in this book was above all to develop theories and to present a conceptual analysis of what digital technologies mean for how social move-ments, power and society interact, rather than provide a complete empirical descriptive account of any one movement.

-

-

www.nytimes.com www.nytimes.com

-

Facebook’s lofty aims were emblazoned even on securities filings: “Our mission is to make the world more open and connected.”

Why not make Facebook more open and connected? This would fix some of the problems.

As usual, I would say that they need to have a way to put some value on the "connections" that they're creating. Not all connections are equal. Some are actively bad, particularly for a productive and positive society.

-

-

bryanalexander.org bryanalexander.org

-

The opening section also lays out come key concepts for the book, including social movement capacities (“social movements’ abilities”) and signals (“their repertoire of protest, like marches, rallies, and occupations as signals of those capacities”) (xi), as well as the problem of tactical freeze (“the inability of these movements to adjust tactics, negotiate demands, and push for

I believe this is an excellent way to share thoughts in a book club.

-

-

www.niemanlab.org www.niemanlab.org

-

As deepfakes make their way into social media, their spread will likely follow the same pattern as other fake news stories. In a MIT study investigating the diffusion of false content on Twitter published between 2006 and 2017, researchers found that “falsehood diffused significantly farther, faster, deeper, and more broadly than truth in all categories of information.” False stories were 70 percent more likely to be retweeted than the truth and reached 1,500 people six times more quickly than accurate articles.

This sort of research should make it eaiser to find and stamp out from the social media side of things. We need regulations to actually make it happen however.

-

-

-

But now it was all for the best: a law of nature, a chance for the monopolists to do good for the universe. The cheerer-in-chief for the monopoly form is Peter Thiel, author of Competition Is for Losers. Labeling the competitive economy a “relic of history” and a “trap,” he proclaimed that “only one thing can allow a business to transcend the daily brute struggle for survival: monopoly profits.”

Sounds like a guy who is winning all of the spoils.

-

-

intermezzo.enculturation.net intermezzo.enculturation.net

-

BUT, our students will not (most) have the economic, cultural, historical provenances nor intention ... the reality of community college students is that most will not produce academic discourse but will eak through multiple courses with minimum academic writing (and if so, poorly) while they will continue their certain continued marginalized communities that are, per Bourdieu, decapitalized (lacking cultural capital), whereas critical rhetoric could address these systemics inegalitarianism.

-

-

-

Entscheidend ist, dass sie Herren des Verfahrens bleiben - und eine Vision für das neue Maschinenzeitalter entwickeln.

Es sieht für mich nicht eigentlich so aus als wären wir jemals die "Herren des Verfahrens" gewesen. Und auch darum geht es ja bei Marx. Denke ich.

-

-

eric.ed.gov eric.ed.gov

-

Instructional Design Strategies for Intensive Online Courses: An Objectivist-Constructivist Blended Approach

This was an excellent article Chen (2007) in defining and laying out how a blended learning approach of objectivist and constructivist instructional strategies work well in online instruction and the use of an actual online course as a study example.

RATING: 4/5 (rating based upon a score system 1 to 5, 1= lowest 5=highest in terms of content, veracity, easiness of use etc.)

Tags

- distance education

- instructional methods

- Instructional systems design; Distance education; Online courses; Adult education; Learning ability; Social integration

- Performance Factors, Influences, Technology Integration, Teaching Methods, Instructional Innovation, Case Studies, Barriers, Grounded Theory, Interviews, Teacher Attitudes, Teacher Characteristics, Technological Literacy, Pedagogical Content Knowledge, Usability, Institutional Characteristics, Higher Education, Foreign Countries, Qualitative Research

- etc556

- etcnau

- online education growth

- constructivism

- instructional design systems

- instructiveness effectiveness

- instructional technology

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.ncolr.org www.ncolr.org

-

The Importance of Interaction in Web-Based Education: A Program-level Case Study of Online MBA Courses

This case study explores perceptions of instructors vs. end-users with web-based training. It examines various technologies and techniques.

RATING: 4/5 (rating based upon a score system 1 to 5, 1= lowest 5=highest in terms of content, veracity, easiness of use etc.)

-

-

eds.a.ebscohost.com.libproxy.nau.edu eds.a.ebscohost.com.libproxy.nau.edu

-

Learning Needs Analysis of Collaborative E-Classes in Semi-Formal Settings: The REVIT Example.

This article explores the importance of analysis of instructional design which seems to be often downplayed particularly in distance learning. ADDIE, REVIT have been considered when evaluating whether the training was meaningful or not and from that a central report was extracted and may prove useful in the development of similar e-learning situations for adult learning.

RATING: 4/5 (rating based upon a score system 1 to 5, 1= lowest 5=highest in terms of content, veracity, easiness of use etc.)

-

-

www.zylstra.org www.zylstra.org

-

They can spew hate amongst themselves for eternity, but without amplification it won’t thrive.

This is a key point. Social media and the way it amplifies almost anything for the benefit of clicks towards advertising is one of its most toxic features. Too often the extreme voice draws the most attention instead of being moderated down by more civil and moderate society.

-

-

www.chronicle.com www.chronicle.com

-

My work, rooted in both theory and practice, reveals three things that are essential to bringing individuals into the circle of change: autonomy, guidance, and a sense of social community, or working toward a larger meaningful goal.

-

-

journals.sagepub.com journals.sagepub.com

-

Humans participate in social learning for a variety of adaptive reasons, such as reducing uncertainty (Kameda and Nakanishi, 2002), learning complex skills and knowledge that could not have been invented by a single individual alone (Richerson and Boyd, 2000; Tomasello, Kruger, and Ratner, 1993), and passing on beneficial cultural traits to offspring (Palmer, 2010). One proposed social-learning mechanism is prestige bias (Henrich and Gil-White, 2001), defined as the selective copying of certain “prestigious” individuals to whom others freely show deference or respect in orderto increase the amount and accuracy of information available to the learner.Prestige bias allows a learner in a novel environment to quickly and inexpensively choose from whom to learn, thus maximizing his or her chances of acquiring adaptive behavioral so lutions toa specific task or enterprisewit hout having to assess directly the adaptiveness of every potential model’s behavior.Learners provide deference to teachers in order to ingratiate themselves with a chosen model, thus gaining extended exposure to that model(Henrich and Gil-White, 2001).New learners can then use that information—who is paying attention to whom—to increase their likelihood of choosing a good teacher.

Throughout this article are several highlighted passages that combine to form this annotation.

This research study presents the idea that the social environment is a self-selected learning environment for adults. The idea of social prestige-bias learning is intriguing because it is derived from the student, not an institution nor instructor. The further idea of selecting whom to learn from based on prestige-bias also creates further questions that warrant a deeper understanding of the learner and the environment which s/he creates to gain knowledge.

Using a previously conducted experiment on success-based learning and learning due to environmental change, this research further included the ideal of social prestige-biased learning.self-selected by the learner.

In a study of 167 participants, three hypotheses were tested to see if learners would select individual learning, social learning, prestige-biased learning (also a social setting), or success-based learning. The experiment tested both an initial learning environment and a learning environment which experienced a change in the environment.

Surprisingly, some participants selected social prestige-biased learning and some success learning and the percentages in each category did not change after the environmental change occurred.

Questions that arise from the study:

- Does social prestige, or someone who is deemed prestigious, equate to a knowledgeable teacher?

- Does the social prestige-biased environment reflect wise choices?

- If the student does not know what s/he does not know, will the social prestige-bias result in selecting the better teacher, or just in selecting a more highly recognized teacher?

- Why did the environmental change have little impact on the selected learning environment?

REFERENCE: Atkinson, C., O’Brien, M.J., & Mesoudi, A. (2012). Adult learners in a novel environment use prestige-biased social learning. Evolutionary Psychology, 10(3), 519-537. Retrieved from (Prestige-biased Learning )

RATINGS content, 9/10 veracity, 8/10 easiness of use, 9/10 Overall Rating, 8.67/10

-

- Oct 2018

-

digitalpedagogy.mla.hcommons.org digitalpedagogy.mla.hcommons.org

-

http://www.zachwhalen.net/posts/how-to-make-a-twitter-bot-with-google-spreadsheets-version-04

useful for automating tweets?

-

-

wiobyrne.com wiobyrne.com

-

Why do people troll? Eight factors are given, which might boil down to:

- Perceived lack of consequences.

- Online mob mentality.

-

-

-

-

Universal education is now widely viewed as one of the basic requirements for a modern society and it serves as a chief catalyst for socio-economic and personal development.

-

-

www.projectinfolit.org www.projectinfolit.org

-

news is stressful and has little impact on the day-to-day routines —use it for class assignments, avoid it otherwise.” While a few students like this one practiced news abstinence, such students were rare.

This sounds a bit like my college experience, though I didn't avoid it because of stressful news (and there wasn't social media yet). I generally missed it because I didn't subscribe directly to publications or watch much television. Most of my news consumption was the local college newspaper.

-

-

medium.com medium.com

-

Research shows Russian trolls working both ends of the political spectrum.

-

-

-

When students are shown quick techniques for judging the veracity of a news source, they will use them. Regardless of their existing beliefs, they will distinguish good sources from bad sources.

-

-

digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu

-

While Silvia and Irene are in a very different place from Lacey, in that they are able to work and attend college, respectively, at this point in their lives, they and their children are still at risk

Lacey no tuvo el privilegio de educación superior lo cual es uno de los mayores determinantes del ingreso y por ende de la salud.

-

-

wiobyrne.com wiobyrne.com

-

The Online Disinhibition Effect (John Suler, 2004) - the lack of restraint shown by some people when communicating online rather than in person. (It can be good as well as bad. How can we reduce the bad behavior?)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Online_disinhibition_effect http://truecenterpublishing.com/psycyber/disinhibit.html

-

-

betterworldsblog.com betterworldsblog.com

-

On the other hand, though much less likely, is the possibility of the gig economy becoming a long-term fixture of capitalism.

Whether or not the gig economy is here to stay, the result will be widespread un- or under-employment caused by technological displacement. Whether workers are gathered into a gig economy or are outright unemployed is what remains to be seen.

-

-

hybridpedagogy.org hybridpedagogy.org

-

“The purpose of education, finally, is to create in a person the ability to look at the world for himself, to make his own decisions… What societies really, ideally, want is a citizenry which will simply obey the rules of society. If a society succeeds in this, that society is about to perish. The obligation of anyone who thinks of himself as responsible is to examine society and try to change and fight it – at no matter what risk. This is the only hope that society has. This is the only way societies change.” — James Baldwin, “A Talk to Teachers,” 1963

-

-

www.theatlantic.com www.theatlantic.com

-

On social media, the country seems to divide into two neat camps: Call them the woke and the resentful. Team Resentment is manned—pun very much intended—by people who are predominantly old and almost exclusively white. Team Woke is young, likely to be female, and predominantly black, brown, or Asian (though white “allies” do their dutiful part). These teams are roughly equal in number, and they disagree most vehemently, as well as most routinely, about the catchall known as political correctness.

-

-

cloud.degrowth.net cloud.degrowth.netdownload2

-

Local- using social media, technology, keeping it horizontal, keeping it simple and humble, celebration is important.

-

the social technologies- knowing how to organize and have effective meeting- from sociocracy and dragon dreaming, agile tools.

There is a lot to learn from, about Teixidora's meeting notes methodology, for example. http://peerproduction.net/editsuite/issues/issue-11-city/peer-reviewed-papers/the-case-of-teixidora-net-in-barcelona/

-

-

www.vox.com www.vox.com

-

We live in a world of bots and trolls and curated news feeds, in which reality is basically up for grabs.

-

-

www.w3.org www.w3.orgMicropub1

-

-

www.powazek.com www.powazek.com

-

The last thing most people need is another microphone. They need something to say. (And time to say it.)

Interesting to hear this from 2006 and looking back now...

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

github.com github.com

-

-

www.mnemotext.com www.mnemotext.com

-

In the past, technology has extended the human body, providing it with tools to act upon the world. But at some point, a tool becomes something more. When does it become part of its user?

In this passage, the author is claiming that with transhumanism and the growing appeal of technology as tools to advance or "extend" the human body, it can blur the lines between what is considered human and what is considered technology. For example, the author previously mentions social media and cell phone use in today's world. In today's society, using smartphones has become second nature. The author is implying that in the near future tools and technology such as anabolic steroids, laser surgery, advanced prosthetic limbs, etc can also become as prominent to humans as cellphones/social media is now.

-

- Sep 2018

-

solid.inrupt.com solid.inrupt.com

-

-

mashable.com mashable.com

-

Snap is also confident that it can reach a high amount of new voters: 80 percent of its users are over 18, so this campaign won't just fall on well-meaning (but still too young) thumbs

Snapchat becomes confident due to being the new form of communication and it happens to be the most activated and number one form of social media. This allows people to be reached out because almost everyone has a Snapchat account.

-

-

www.lostgarden.com www.lostgarden.com

-

We can’t force two people to become friends, nor should we want to.

How many social engineers does it take to change a light bulb? An infinite number. That's why they leave you in the dark till you become the change you seek and make your own light to live by.

If you cant force two people to become friends, then how do 'diplomats' (political manipulators?) profess to do the same thing with entire nations? Especially while so often, using the other hand to deal the deck for other players, in a game of "let's you and him fight"; or just being bloody mercenaries with sheer might is right political ethos installed under various euphemistic credos. 'My country right or wrong' or 'Mitt Got Uns' or ...to discover weapons of mass destruction...etc.

So much for politics and social engineering, but maybe we can just be content with not so much forcing two people to be friends, as forcing them to have sex while we're filming them, so we can create more online amateur porn content. LOL ;)

-

-

www.slideshare.net www.slideshare.net

-

www.makeuseof.com www.makeuseof.com

-

Facebook does not allow third-party apps to display your newsfeed. This applies to Hootsuite. For this reason, you’ll always have to use Facebook natively. The same pretty much goes for Instagram.

Facebook does not allow third-party apps to display your newsfeed. This applies to Hootsuite. For this reason, you’ll always have to use Facebook natively. The same pretty much goes for Instagram.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

tools.ietf.org tools.ietf.org

-

This specification defines the WebFinger protocol, which can be used to discover information about people or other entities on the Internet using standard HTTP methods. WebFinger discovers information for a URI that might not be usable as a locator otherwise, such as account or email URIs.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

blog.joinmastodon.org blog.joinmastodon.org

-

All of these platforms are different and they focus on different needs. And yet, the foundation is all the same: people subscribing to receive posts from other people. And so, they are all compatible. From within Mastodon, Pleroma, Misskey, PixelFed and PeerTube users can be followed and interacted with all the same.

-

-

activitypub.rocks activitypub.rocks

-

ActivityPub is a decentralized social networking protocol based on the ActivityStreams 2.0 data format. ActivityPub is an official W3C recommended standard published by the W3C Social Web Working Group. It provides a client to server API for creating, updating and deleting content, as well as a federated server to server API for delivering notifications and subscribing to content.

-

-

indieweb.org indieweb.orgIndieWeb1

-

-

webmention.io webmention.io

-

<link rel="pingback" href="https://webmention.io/username/xmlrpc" /> <link rel="webmention" href="https://webmention.io/username/webmention" />

-

-

github.com github.com

-

Federated blogging application, thanks to ActivityPub

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

forumpa-librobianco-innovazione-2018.readthedocs.io forumpa-librobianco-innovazione-2018.readthedocs.io

-

promuoverne

Bando "Blockchains for Social Good": links funzionanti:

https://ec.europa.eu/research/eic/index.cfm?pg=prizes_blockchains

https://ec.europa.eu/research/eic/pdf/infographics/eic_horizon-prize-blockchains.pdf

-

Appare necessario, per quell’indispensabile ripristino delle condizioni della fiducia, avere la massima attenzione alle diversità di ogni tipologia di amministrazione, dal piccolo comune al grande ente centrale, mettendo in evidenza sempre le tante eccellenze presenti, nate spesso dell’impegno di una unità organizzativa e dei suoi dirigenti, che devono trovare pubblicità, apprezzamento dell’opinione pubblica, effettivi riconoscimenti da parte del governo centrale. Anche appoggiandosi a agenzie indipendenti, il governo dovrebbe curare un catalogo ricco e aggiornato di “buoni esempi”, che porti con sé anche la strumentazione amministrativa utile per replicarlo.

… Valorizzare le buone pratiche realizzate dagli enti italiani e promuoverne la diffusione dovrebbe essere un obiettivo prioritario utilizzando il bando Horizon 2020 "Blockchains for Social Good", links: [https://ec.europa.eu/research/eic/index.cfm?pg=prizes_blockchains] [https://ec.europa.eu/research/eic/pdf/infographics/eic_horizon-prize-blockchains.pdf] Il bando ha il seguente Timetable aggiornato a maggio 2018:<br> 16 May 2018 – contest opens ; 2 April 2019 – deadline for registration of interest ; 3 September 2019 – deadline to submit applications.<br> This prize aims to develop solutions to social innovation challenges using distribute ledger technology. The contest is open to individuals, groups, organisations and companies.

-

-

www.mnemotext.com www.mnemotext.com

-

Oh no I’m sure any delta is brighter than an epsilon like those. That’s one of the wonderful things about being a gamma. We’re not too stupid and we’re not too bright to be a gamma is to be just right

this part of the dialogue creates a great sense of social and class inequality in the world created by this movie. Deltas are considered wise and have greater responsibilities whereas gammas are considered somewhere in between and are in charge of more mundane matters.

-

-

hapgood.us hapgood.us

-

Rather than imagine a timeless world of connection and multiple paths, the Stream presents us with a single, time ordered path with our experience (and only our experience) at the center.

-

-

motherboard.vice.com motherboard.vice.com

-

Trump’s digital strategy, Singer and Brooking argue, is not unlike militant groups and street gangs that leverage the viral web to tell a compelling story about policy, religious dogma, or their own perceived fearsomeness, all in an engaging voice, while repeatedly targeting exactly the right audience to trigger a dopamine response or sheer terror, both online and IRL. "To 'win' the internet, one must learn how to fuse these elements of narrative, authenticity, community, and inundation," Singer and Brooking write. "And if you can 'win' the internet, you can win silly feuds, elections, and deadly serious battles."

-