I just finished my Bachelor thesis working with Obsidian! by u/ThiIsAnkou

100 literature- and about 650 permanentnotes. Thanks to Obsidian and Zettelkasten!

I just finished my Bachelor thesis working with Obsidian! by u/ThiIsAnkou

100 literature- and about 650 permanentnotes. Thanks to Obsidian and Zettelkasten!

Luhmann, Niklas. “Improved Translation of ‘Communications with Zettelkastens.’” Translated by Sascha Fast. Zettelkasten Method, April 5, 2023. https://zettelkasten.de/communications-with-zettelkastens/.

I decided to translate the German “Zettelkasten” as “Zettelkasten” since I consider this an established term.

An example of a bi-lingual German-English speaker/writer specifically translating and using Zettelkasten as an established word in English.

Without variation on given ideas, there are no possibilities of scrutiny and selection of innovations. Therefore, the actual challenge becomes generating incidents with sufficiently high chances of selection.

The value of a zettelkasten is as a tool to actively force combinatorial creativity—the goal is to create accidents or collisions of ideas which might have a high chance of being discovered and selected for.

Compared to this structure that offers actualizable connection possibilities, the relevance of the actual content of the note subsides. Much of it quickly becomes useless or is unusable for a concrete occasion. That is true for both collected quotes, which are only worth collecting when they are exceptionally concise, and for your own thoughts.

Luhmann felt that quotations aren't worth collecting unless they were "exceptionally concise, and for your own thoughts."

The Zettelkasten needs a couple of years to reach critical mass.

I find that this is not the case. Even a few hundred cards is more than enough to create something interesting.

Though what does he mean specifically by "critical mass"?

A Zettelkasten that is constructed based on our instructions can achieve high independence. There may be other ways to achieve this goal. The described reduction to a fixed-placement (but merely formal) order, and the corresponding combination of order and disorder, is at least one of them.

The structural components of Luhmann's zettelkasten which allow for "achieving high independence" are also the same structures found in an indexed commonplace book: namely fixed placement (formally by the order in which things are found and collected) as well as combinations of order and disorder (the methods by which they can be retrieved and read).

Similarly, you must give up the assumption that there are privileged places, notes of special and knowledge-ensuring quality. Each note is just an element that gets its value from being a part of a network of references and cross-references in the system. A note that is not connected to this network will get lost in the Zettelkasten, and will be forgotten by the Zettelkasten.

This section is almost exactly the same as Umberto Eco's description of a slip box practice:

No piece of information is superior to any other. Power lies in having them all on file and then finding the connections. There are always connections; you have only to want to find them. -- Umberto Eco. Foucault's Pendulum

See: https://hypothes.is/a/jqug2tNlEeyg2JfEczmepw

Interestingly, these structures map reasonably well onto Paul Baran's work from 1964:

The subject heading based filing system looks and functions a lot like a centralized system where the center (on a per topic basis) is the subject heading or topical category and the notes related to that section are filed within it. Luhmann's zettelkasten has the feel of a mixture of the decentralized and distributed graphs, but each sub-portion has its own topology. The index is decentralized in nature, while the bibliographical section/notes are all somewhat centralized in form.

Cross reference:<br /> Baran, Paul. “On Distributed Communications: I. Introduction to Distributed Communications Networks.” Research Memoranda. Santa Monica, California: RAND Corporation, August 1964. https://doi.org/10.7249/RM3420.

(Alternating numbers and letters helps the memory and may be an optical aid when searching notes, but is of course not enough).

The alternation of letters and numbers helps to create some visual differentiation of various branches, but how does it help the memory? Help as in it's easier to search for these sorts of combinations versus remembering strings of only numbers?

A content-based system (like a book’s table of contents) would mean that you would have to adhere to a single structure forever (decades in advance!).

Starting a zettelkasten practice with a table of contents as the primary organization is difficult due to planning in advance.

There are two ways for a communication system to maintain its integrity over long periods of time: you need to decide for either highly technical specialisation, or for a setup that incorporates coincidence and ad hoc generated information. Translated to note collections: you can choose a setup categorized by topics, or an open one. We chose the latter and, after 26 successful years with only occasionally difficult teamwork, we can report that this way is successful – or at least possible.

Luhmann indicates that there are different methods for keeping note collections and specifically mentions categorizing things by topics first. It's only after this that he mentions his own "open" system as being a possible or successful one.

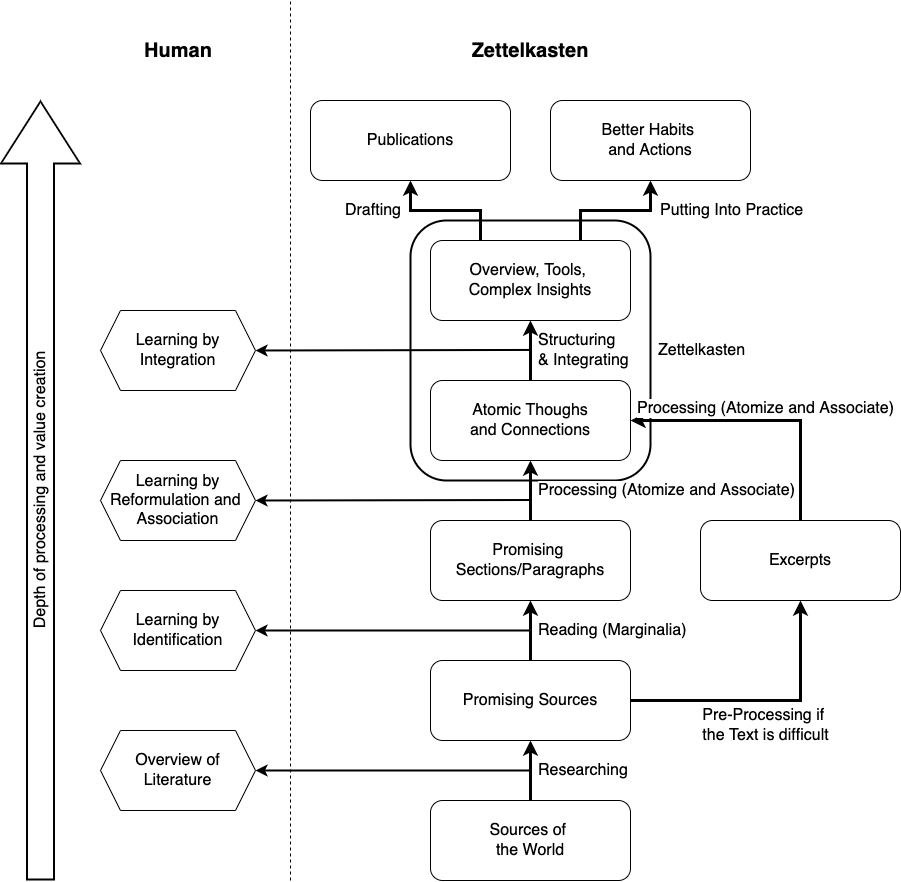

Fast, Sascha. “Field Report #5: How I Prepare Reading and Processing Effective Notetaking by Fiona McPherson.” Zettelkasten Method (blog), March 29, 2022. https://zettelkasten.de/posts/field-report-5-reading-processing-effective-notetaking-mcpherson/.

Sascha Fast's conceptual diagram of Human and Zettelkasten

How do I store when coming across an actual FACT? .t3_12bvcmn._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postBodyLink-VisitedLinkColor: #989898; } questionLet's say I am trying to absorb a 30min documentary about the importance of sleep and the term human body cells is being mentioned, I want to remember what a "Cell" is so I make a note "What is a Cell in a Human Body?", search the google, find the definition and paste it into this note, my concern is, what is this note considered, a fleeting, literature, or permanent? how do I tag it...

reply to u/iamharunjonuzi at https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/12bvcmn/how_do_i_store_when_coming_across_an_actual_fact/

How central is the fact to what you're working at potentially developing? Often for what may seem like basic facts that are broadly useful, but not specific to things I'm actively developing, I'll leave basic facts like that as short notes on the source/reference cards (some may say literature notes) where I found them rather than writing them out in full as their own cards.

If I were a future biologist, as a student I might consider that I would soon know really well what a cell was and not bother to have a primary zettel on something so commonplace unless I was collecting various definitions to compare and contrast for something specific. Alternately as a non-biologist or someone that doesn't use the idea frequently, then perhaps it may merit more space for connecting to others?

Of course you can always have it written along with the original source and "promote" it to its own card later if you feel it's necessary, so you're covered either way. I tend to put the most interesting and surprising ideas into my main box to try to maximize what comes back out of it. If there were 2 more interesting ideas than the definition of cell in that documentary, then I would probably leave the definition with the source and focus on the more important ideas as their own zettels.

As a rule of thumb, for those familiar with Bloom's taxonomy in education, I tend to leave the lower level learning-based notes relating to remembering and understanding as shorter (literature) notes on the source's reference card and use the main cards for the higher levels (apply, analyze, evaluate, create).

Ultimately, time, practice, and experience will help you determine for yourself what is most useful and where. Until you've developed a feel for what works best for you, just write it down somewhere and you can't really go too far wrong.

zettelkasten

(free of this context, but I need somewhere just to place this potential title/phrase...)

Purpose Driven Zettelkasten

Hypothesis Animated Intro, 2013. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QCkm0lL-6lc.

This was an early animation for Hypothes.is as a tool. It was on one of their early homepages and is (still) a pretty good encapsulation of what they do and who they are as a tool for thought.

In the fall of 2015, she assigned students to write chapter introductions and translate some texts into modern English.

continuing from https://hypothes.is/a/ddn4qs8mEe2gkq_1T7i3_Q

Potential assignments:

Students could be tasked with finding new material or working off of a pre-existing list.

They could individually be responsible for indexing each individual sub-text within a corpus by: - providing a full bibliography; - identifying free areas of access for various versions (websites, Archive.org, Gutenberg, other OER corpora, etc.); Which is best, why? If not already digitized, then find a copy and create a digital version for inclusion into an appropriate repository. - summarizing the source in general and providing links to how it fits into the broader potential corpus for the class. - tagging it with relevant taxonomies to make it more easily searchable/selectable within its area of study - editing a definitive version of the text or providing better (digital/sharable) versions for archiving into OER repositories, Project Gutenberg, Archive.org, https://standardebooks.org/, etc. - identifying interesting/appropriate tangential texts which either support/refute their current text - annotating their specific text and providing links and cross references to other related texts either within their classes' choices or exterior to them for potential future uses by both students and teachers.

Some of this is already with DeRosa's framework, but emphasis could be on building additional runway and framing for helping professors and students to do this sort of work in the future. How might we create repositories that allow one a smörgåsbord of indexed data to relatively easily/quickly allow a classroom to pick and choose texts to make up their textbook in a first meeting and be able to modify it as they go? Or perhaps a teacher could create an outline of topics to cover along with a handful of required ones and then allow students to pick and choose from options in between along the way. This might also help students have options within a course to make the class more interesting and relevant to their own interests, lives, and futures.

Don't allow students to just "build their own major", but allow them to build their own textbooks and syllabi with some appropriate and reasonable scaffolding.

In the fall of 2015, she assigned students to write chapter introductions and translate some texts into modern English.

Perhaps of interest here, would not be a specific OER text, but an OER zettelkasten or card index that indexes a variety of potential public domain or open resources, articles, pieces, primary documents, or other short readings which could then be aggregated and tagged to allow for a teacher or student to create their own personalized OER text for a particular area of work.

If done well, a professor might then pick and choose from a wide variety of resources to build their own reader to highlight or supplement the material they're teaching. This could allow a wider variety of thinking and interlinking of ideas. With such a regiment, teachers are less likely to become bored with their material and might help to actively create new ideas and research lines as they teach.

Students could then be tasked with and guided to creating a level of cohesiveness to their readings as they progress rather than being served up a pre-prepared meal with a layer of preconceived notions and frameworks imposed upon the text by a single voice.

This could encourage students to develop their own voices as well as to look at materials more critically as they proceed rather than being spoon fed calcified ideas.

Zettel, right

Smith, Chris. “Thesaurus Linguae Latinae: How the World’s Largest Latin Lexicon Is Brought to Life.” De Gruyter Conversations, July 5, 2021. https://blog.degruyter.com/thesaurus-linguae-latinae-how-the-worlds-largest-latin-lexicon-is-brought-to-life/.

Basic overview article without much direct data/insight

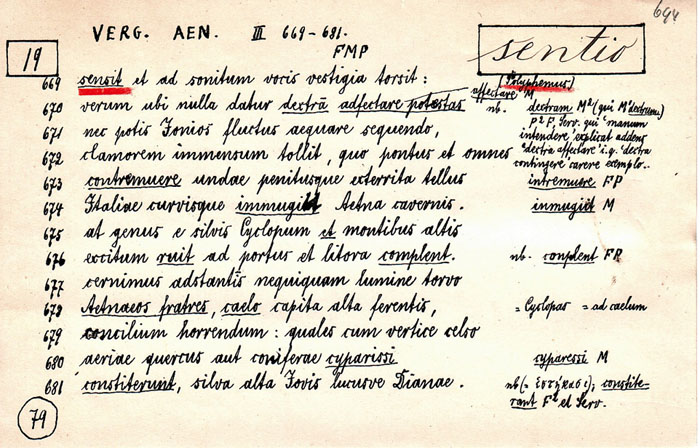

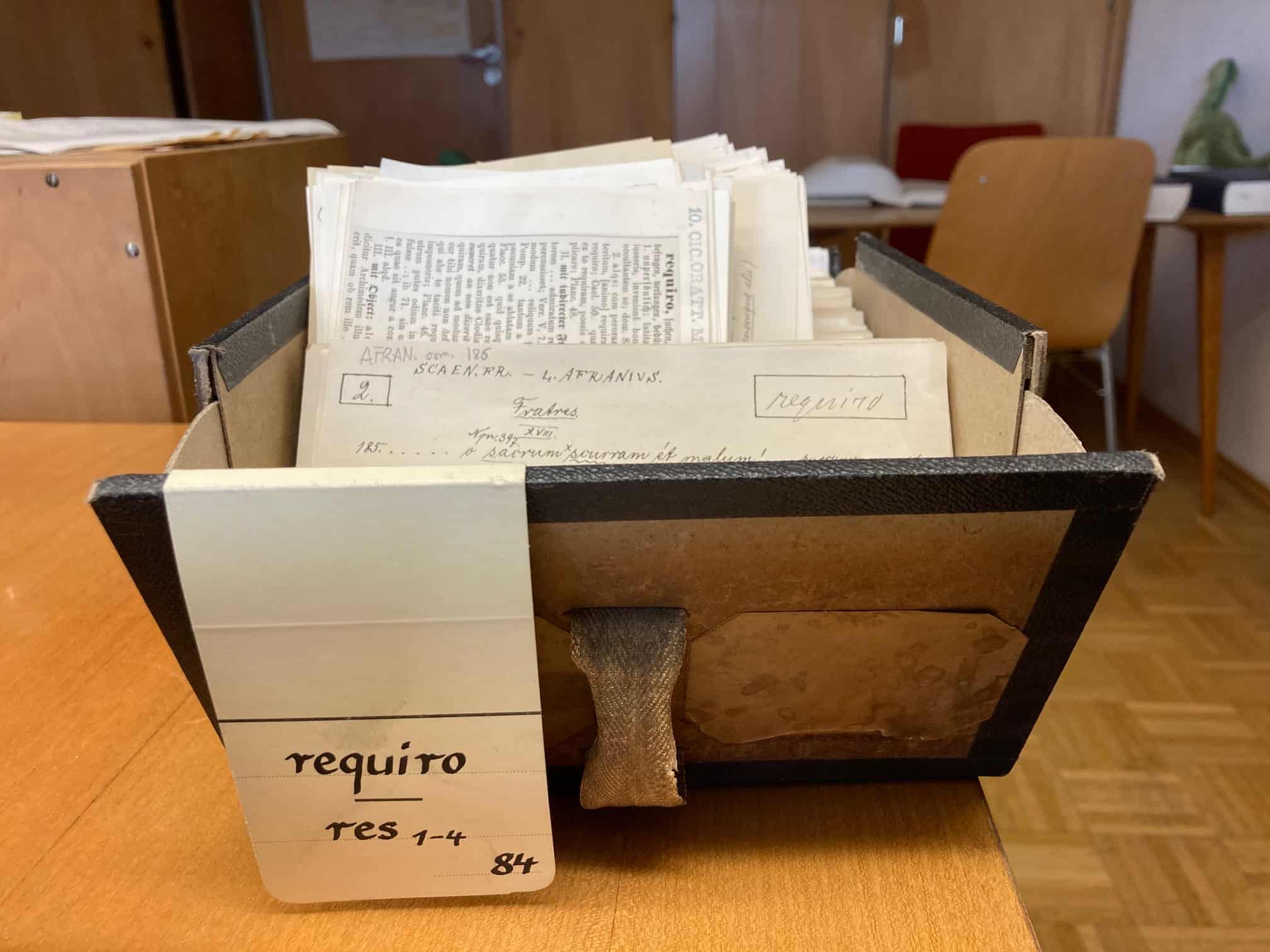

Slip box for the word ‘requiro’ © Adam Gitner

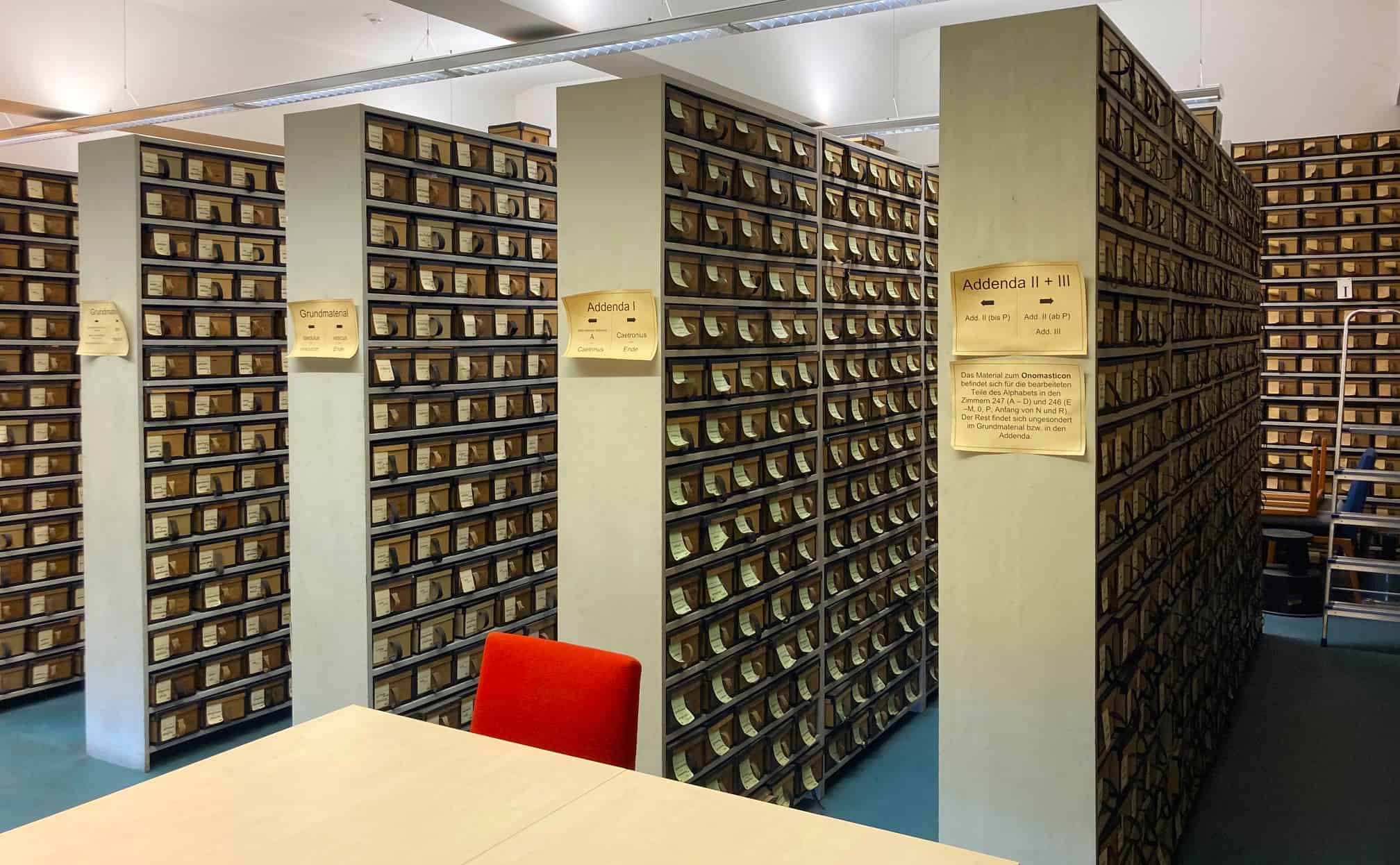

TLL slip archive © Adam Gitner

A sample of the note cards the scholars are using to assemble the comprehensive Latin dictionary. Courtesy of Samuel Beckelhymer. hide caption toggle caption Courtesy of Samuel Beckelhymer.

The archive contains boxes filled with notes on each Latin word. In most cases, the scholars made the notes more than a century ago. Courtesy of Nigel Holmes hide caption toggle caption Courtesy of Nigel Holmes

Stefano Rocchi, a researcher on the Thesaurus Linguae Latinae, the comprehensive Latin dictionary that has been in the works since 1894 in Germany. Researchers are currently working on the letters N and R. They don't expect to finish until around 2050. BAdW/Foto Janina Amendt hide caption toggle caption BAdW/Foto Janina Amendt

They both talk, though, about going over material again and again. The process of writing an article involves putting words in chronological order, but also creating branching, sub-dividing trees of syntax and semantics.

Interesting to see a reference the branching nature of the meanings of an individual word which has multiple ways of being categorized.

The TLL categorizes words alphabetically first and then by chronologically second. The rest of the structure shakes out from there as editors write articles for each of the words.

The TLL was moved to a monastery in Bavaria during WWII because they were worried that the building that contained the zettelkasten would be bombed and it actually was.

The slips have been microfilmed and a copy of them is on store at Princeton as a back up just i case.

[01:17:00]

Remember the Thesaurus is a work of the human brain and therefore it is fallible. —Kathleen M. Coleman

replace Thesaurus with zettelkasten...

Basic statistics regarding the TLL: - ancient Latin vocabulary words: ca. 55,000 words - 10,000,000 slips - ca. 6,500 boxes - ca. 1,500 slips per box - library 32,000 volumes - contributors: 375 scholars from 20 different countries - 12 Indo-European specalists - 8 Romance specialists - 100 proof-readers - ca. 44,000 words published - published content: 70% of the entire vocabulary - print run: 1,350 - Publisher: consortium of 35 academies from 27 countries on 5 continents

Longest remaining words: - non / 37 boxes of ca 55,500 slips - qui, quae, quod / 65 boxes of ca. 96,000 slips - sum, esse, fui / 54.5 boxes of ca. 81,750 slips - ut / 35 boxes of ca 52,500 slips

Note that some of these words have individual zettelkasten for themselves approaching the size of some of the largest personal collections we know about!

[18:51]

The Thesaurus Linguae Latinae used the Meusel system for creating Zettel by utilizing double folio sheets onto which they copied text in hectographic ink which can be reproduced by lithography before cutting them up into slips.

Done alphabetically and then secondarily by chronological time. (Indicated in a box on the top left of each slip.) The number of copies of each slip is written in the bottom left hand corner and circled.

Forschung: Der Thesaurus linguae Latinae. Munich, Germany: Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C3Eqt2QBKNs.

Based on the history and usage of horreum here in this first episode of the Thesaurus Linguae Latinae podcast, a project featuring a 10+ million slip zettelkasten at its core, I can't help but think that not only is the word ever so apropos for an introduction, but it does quite make an excellent word for translating the idea of card index in English or Zettelkasten from German into Latin.

My horreum is a storehouse for my thoughts and ideas which nourishes my desire to discover and build upon my knowledge.

This seems to be just the sort of thing that Jeremy Cherfas might appreciate on multiple levels.

Project: Thesaurus linguae Latinae<br /> from Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften

The advent of computer technology facilitated the assembly of the Demotic Dictionary, which unlike its older sister, the Chicago Assyrian Dictionary, could be organized electronically rather than on index cards.

The Chicago Demotic Dictionary compiled by the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago was facilitated by computers compared with the Chicago Assyrian Dictionary which relied on index cards.

Hayes, William C. Review of Historical Records of Rameses III, by William F. Edgerton and John A. Wilson. American Journal of Archaeology 40, no. 4 (1936): 558–59. https://doi.org/10.2307/498809.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/498809

...have been diligently consulted and compared with the present versions and the authors have also availed themselves of the invaluable material contained in the Zettelkasten of the Berlin Wirterbuch der...

This is the oldest appearance of the word "Zettelkasten" appearing in a journal article which I could find on JSTOR.

I'm not surprised it's in a journal in the humanities and specifically on archaeology.

Update: even better, this has introduced me to a massive new ZK: Wörterbuch der ägyptischen Sprache!

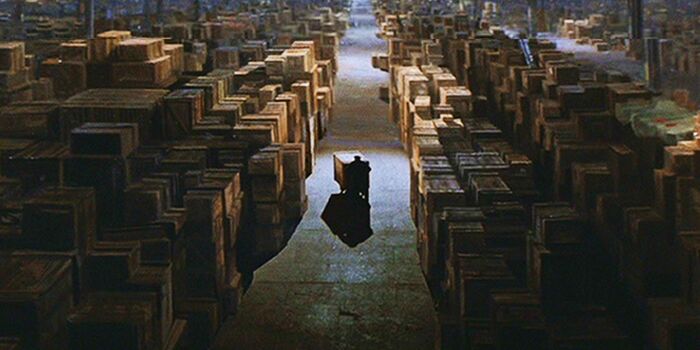

Where is Indiana Jones' zettelkasten?!

https://aaew.bbaw.de/digitalisiertes-zettelarchiv

The Digitized Card Archive ( DZA ) of the Dictionary of the Egyptian Language (Wörterbuch der ägyptischen Sprache) has been available on the Internet since 1999. The archive can be searched at: https://aaew.bbaw.de/tla/servlet/DzaIdx.

Since 2004, the materials and query functions have been integrated into the larger Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae project at https://aaew.bbaw.de/thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.

The Wörterbuch der ägyptischen Sprache was an international collaborative zettelkasten project begun in 1897 and finally published as five volumes in 1926.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/W%C3%B6rterbuch_der_%C3%A4gyptischen_Sprache

Structures and Transformations of the Vocabulary of the Egyptian Language: Text and Knowledge Culture in Ancient Egypt. “Altägyptisches Wörterbuch: Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften 1999,” 2007. https://web.archive.org/web/20180627163317/https://aaew.bbaw.de/wbhome/Broschuere/index.html.

Wesentlich gefördert durch die Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, wurde in den Jahren 1997 und 1998 das gesamte Zettelarchiv des Wörterbuches der ägyptischen Sprache, insgesamt 1,5 Millionen Blätter, verfilmt und digitalisiert. Dadurch wurde dieses einmalige Archiv auch erstmals gesichert.

With support from the German Research Foundation, the 1.5 million sheets of the Wörterbuch der ägyptischen Sprache began to be digitized and put online in 1997.

Die schiere Menge sprengt die Möglichkeiten der Buchpublikation, die komplexe, vieldimensionale Struktur einer vernetzten Informationsbasis ist im Druck nicht nachzubilden, und schließlich fügt sich die Dynamik eines stetig wachsenden und auch stetig zu korrigierenden Materials nicht in den starren Rhythmus der Buchproduktion, in der jede erweiterte und korrigierte Neuauflage mit unübersehbarem Aufwand verbunden ist. Eine Buchpublikation könnte stets nur die Momentaufnahme einer solchen Datenbank, reduziert auf eine bestimmte Perspektive, bieten. Auch das kann hin und wieder sehr nützlich sein, aber dadurch wird das Problem der Publikation des Gesamtmaterials nicht gelöst.

Google translation:

The sheer quantity exceeds the possibilities of book publication, the complex, multidimensional structure of a networked information base cannot be reproduced in print, and finally the dynamic of a constantly growing and constantly correcting material does not fit into the rigid rhythm of book production, in which each expanded and corrected new edition is associated with an incalculable amount of effort. A book publication could only offer a snapshot of such a database, reduced to a specific perspective. This too can be very useful from time to time, but it does not solve the problem of publishing the entire material.

While the writing criticism of "dumping out one's zettelkasten" into a paper, journal article, chapter, book, etc. has been reasonably frequent in the 20th century, often as a means of attempting to create a linear book-bound context in a local neighborhood of ideas, are there other more complex networks of ideas which we're not communicating because they don't neatly fit into linear narrative forms? Is it possible that there is a non-linear form(s) based on network theory in which more complex ideas ought to better be embedded for understanding?

Some of Niklas Luhmann's writing may show some of this complexity and local or even regional circularity, but perhaps it's a necessary means of communication to get these ideas across as they can't be placed into linear forms.

One can analogize this to Lie groups and algebras in which our reading and thinking experiences are limited only to local regions which appear on smaller scales to be Euclidean, when, in fact, looking at larger portions of the region become dramatically non-Euclidean. How are we to appropriately relate these more complex ideas?

What are the second and third order effects of this phenomenon?

An example of this sort of non-linear examination can be seen in attempting to translate the complexity inherent in the Wb (Wörterbuch der ägyptischen Sprache) into a simple, linear dictionary of the Egyptian language. While the simplicity can be handy on one level, the complexity of transforming the entirety of the complexity of the network of potential meanings is tremendously difficult.

Auch die Korrektur einer Textstelle ist in der Datenbank sofort global wirksam. Im Zettelarchiv dagegen ist es kaum zu leisten, alle alphabetisch einsortierten Kopien eines bestimmten Zettels zur Korrektur wieder aufzufinden.

Correcting a text within a digital archive or database allows the change to propagate to all portions of the collection compared with a physical card index which has the hurdle of multiple storage and requires manual changes on all of the associated copies.

This sort of affordance can be seen in more modern note taking tools like Obsidian which does this sort of work with global search and replace of double bracketed words which change everywhere in the collection.

Ausgangspunkt und Zentrum der Arbeit am Altägyptischen Wörterbuch ist die Anlage eines erschöpfenden Corpus ägyptischer Texte.

In the early twentieth century one might have created a card index to study a large textual corpus, but in the twenty first one is more likely to rely on a relational database instead.

In looking at the uses of and similarities between Wb and TLL, I can't help but think that these two zettelkasten represented the state of the art for Large Language Models and some of the ideas behind ChatGPT

Abb. 9 Im Normalfall erarbeitete man jedoch eine detaillierte interne Feinsortierung des Belegmaterials häufiger Wörter. Naturgemäß hätte jede Dimension der Analyse (chronologisch, grammatisch, semantisch, graphisch) die Grundlage einer eigenen Sortierordnung bilden können.

Alternate sort orders for the slips for the Wb include chronological, grammatical, semantic, and graphic, but for teasing out the meanings the original sort order was sufficient. Certainly other sort orders may reveal additional subtleties.

The Wörterbuch der ägyptischen Sprache slip box collection is almost 17 times the size of Niklas Luhmann's by number of slips (1,500,000/90,000 = 16.67) and 58.81 times the size in number of boxes (1588/27).Though keep in mind that due to the multiple storage here each card was copied ~40 times, so if only only counts individual cards then the collection would have been (1.5M/40) 375,000 slips, which is still more than 4 times the size of Luhmann's collection of slips.

See: https://hypothes.is/a/QMYAQMztEe2disvmvCAEAA for source of Wb number source.

Insgesamt wurde auf diese Art ein Corpus von ca. 1,5 Millionen Textwörtern erschlossen. Allein dieser Teil des Zettelarchivs des Wörterbuches der ägyptischen Sprache füllt heute 1588 Zettelkästen.

The zettelkasten for the Wörterbuch der ägyptischen Sprache comprises approximately 1.5 million slips for words and the card archive fills 1588 boxes.

Textmaterials war zunächst ein technisches Problem. Angelehnt an die Praxis des Thesaurus Linguae Latinae wurde ein ausgeklügeltes Verzettelungssystem entworfen. Die gesammelten Texte wurden dazu in Passagen von jeweils etwa 30 Wörtern Länge unterteilt und in hieroglyphischer Form auf Zettel im Postkartenformat geschrieben. Die Bezeichnung des verzettelten Texts und der aktuellen Textpassage wurden in der Kopfzeile notiert. Wo erforderlich, sind auch Notizen zum szenischen Kontext einer Inschrift beigefügt, und meistens wurde der Versuch gemacht, eine Übersetzung der Textpassage zu geben. Gerade die Lückenhaftigkeit dieser Übersetzungen zeigt deutlich, wie unsicher man sich damals noch an vielen Stellen sein mußte. Die gesamte primäre Textaufnahme hatte bis zu einem gewissen Grade vorläufigen Charakter und war nicht als abschließende Analyse der Textstelle, sondern als Ausgangspunkt eines vertiefenden, vergleichenden Studiums gedacht. Dass heute viele der damals problematischen Passagen keine Schwierigkeiten mehr machen, ist zuallererst ein Verdienst des Wörterbuches und belegt, wie dieses das philologische Textverständnis auf ein neues Niveau gehoben hat.

The structure of the filing system for the Wörterbuch der ägyptischen Sprache was designed based on the work done for the Thesaurus Linguae Latinae started in 1894. Texts in the collection were roughly divided into passages of about 30 words and written in hieroglyphic form on postcard-sized slips of paper. The heading contained the designation of the text and the body included the texts' context (inscriptions, etc.) as well as a preliminary translation of the passage.

These passages were then cross-referenced with other occurrences of the hieroglyphics to provide better progressive translations which ultimately appeared in the final manuscript. As a result some of the translations on the cards were incomplete as work proceeded and cross-comparisons of individual words were puzzled out.

A slip showing a passage of text from the victory stele of Sesostris III at the Nubian fortress of Semna. The handwriting is that of project leader Adolf Erman, who had "already struggled with the text as a high school student".

A slip showing a passage of text from the victory stele of Sesostris III at the Nubian fortress of Semna. The handwriting is that of project leader Adolf Erman, who had "already struggled with the text as a high school student".

McCauley, Edward Y. “A Dictionary of the Egyptian Language.” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 16, no. 1 (1883): 1–241. https://doi.org/10.2307/1005403.

Prior to the Wörterbuch der ägyptischen Sprache, but nothing brilliant with respect to use of a zettelkasten to create.

Oxford English Dictionary first attests 'commonplace' (from the Latin 'locus communis') asnoun in 1531 and a verb in 1656; 'excerpt' (from the Latin 'excerpere') as a verb in 1536 and anoun in 1656.

The split between the ideas of commonplace book and zettelkasten may stem from the time period of the Anglicization of the first. If Gessner was just forming the tenets of a zettelkasten practice in 1548 and the name following(?) [what was the first use of zettelkasten?] while the word commonplace was entering English in 1531 using a book format, then the two traditions would likely have been splitting from that point forward in their different areas.

JSTOR has at least a dozen articles/journal entries in English referencing "zettelkasten" (mostly disparagingly). I searched a while back, and the earliest I found then was from 1967. But, there were others from the 70s, 80s, 90s, etc.

reply to u/taurusnoises at https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/11ov8qp/comment/jbvdyx8/?utm_source=reddit&utm_medium=web2x&context=3

Thanks for the tip Bob, JSTOR was a reasonably quick/easy search (compared to the larger list I've got that'll take some manual digging.) The vast majority of instances I found within JSTOR were in full German contexts, and many definitely were in a negative contextual light (generally as an epithet—one went so far as to mention a smell— describing authors' poor structure, over-reliance on ZK, argument, or writing style, potentially as not providing appropriate context.) Fascinatingly the number of appearances of zettelkasten in any language began in the early 1900s and have grown from a dozen every decade to 150 this past decade with a marked increase in the 1980s and 90s.

The oldest one I found in an English language article was from:

Hayes, William C. Review of Historical Records of Rameses III, by William F. Edgerton and John A. Wilson. American Journal of Archaeology 40, no. 4 (1936): 558–59. https://doi.org/10.2307/498809. (JSTOR https://www.jstor.org/stable/498809)

All available earlier copies and parallel texts have been diligently consulted and compared with the present versions and the authors have also availed themselves of the invaluable material contained in the Zettelkasten of the Berlin Wörterbuch der ägyptischen Sprache.

Potentially not the very first English appearance, but 1936 is reasonably early. I wasn't surprised that it appeared in an archaeology journal.

Of particular interest is that it provides an indication that the "Berlin Dictionary" or the Dictionary of the Egyptian Language, which was begun in 1897 just two years after the beginning of the Mundaneum by Paul Otlet and Henri La Fontaine, began life as a multi-user zettelkasten. For those who are looking for the rare versions of collaborative zettelkasten, this is a new version for folks to research.

Allavailable earlier copies and parallel texts havebeen diligently consulted and compared with thepresent versions and the authors have also availedthemselves of the invaluable material contained inthe Zettelkasten of the Berlin Wirterbuch der

ägyptischen Sprache.

This is the first use of the word Zettelkasten in an English (non-German) context in JSTOR that I've been able to find.

Still likely not the first appearance, but reasonably early...

Süss, Wilhelm. Karl Morgenstern (1770-1852), eloquentiae, I - ll. Gr. et Lat., antiquitatum, aesthetices et historiae litterarum atque artis p.p.o. simulque bibliothecae academicae praefectus : ein kulturhistorischer Versuch. Dorpat : Mattiesen. Accessed March 24, 2023. https://jstor.org/stable/community.32963350.

Karl Morgenstern (1770-1852), eloquence, I - ll. Gr. and Lat., antiquities, aesthetics and history of literature and art ppo and at the same time in charge of the academic library: ein kulturhistorischer Versuch<br /> 1928<br /> Sweet, William<br /> Karl Morgenstern (1770-1852), eloquence, I - ll. Gr. and Lat., antiquities, aesthetics and history of literature and art ppo and at the same time in charge of the academic library: ein kulturhistorischer Versuch,

... the ancient ones etc., his note boxes filled with quotations He compares the nations, speaks of the Germans who, since Gellert, “read and write and read what. has, eyes.. other nation has one, Leipziger which boasts such staid mass catalogues?” But not the word interpreters of the ancients, who the ...

Stroebe, Lilian L. “Die Stellung Des Mittelhochdeutschen Im College-Lehrplan.” Monatshefte Für Deutsche Sprache Und Pädagogik, 1924, 27–36. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44327729

The place of Middle High German in the college curriculum<br /> Lilian L. Stroebe<br /> Monthly magazines for German language and pedagogy (1924), pp. 27-36

... of course to the reading material. Especially in the field of etymology it is easy to stimulate the pupils' independence. For years I have had each of my students create an etymological card dictionary with good success, and I see that at the end of the course they have this card box ...

Müller, A., and A. Socin. “Heinrich Thorbecke’s Wissenschaftlicher Nachlass Und H. L. Fleischer’s Lexikalische Sammlungen.” Zeitschrift Der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 45, no. 3 (1891): 465–92. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43366657

Title translation: Heinrich Thorbecke's scientific estate and HL Fleischer's lexical collections Journal of the German Oriental Society

... wrote a note. There are about forty smaller and larger card boxes , some of which are not classified, but this work is now being undertaken to organize the library. In all there may be about 100,000 slips of paper; Of course, each note contains only one ...

Example of a scholar's Nachlass which contains a Zettelkasten.

Based on this quote, there is a significant zettelkasten example here.

Review: [Untitled] Roman und Satire im 18. Jahrhundert: Ein Beitrag zur Poetik by Jörg Schönert Review by: J. D. Workman Monatshefte, Vol. 62, No. 4 (Winter, 1970), pp. 420-421 https://www.jstor.org/stable/30156502

...form of the period for which there are no classical "rules." Schinert musters his evidence in an interesting and generally very lucid manner, although at times he may seem somewhat overzealous, if not indeed repetitious, in assembling all the data: at times one detects the faint odor of the Zettelkasten...

faint odor! ha! and in an English language document.

"Neither of us seems to be good for professors." The lectures by Jacob (1785-1863) and Wilhelm Grimm (1786-1859) Steffen Martus Journal for German Studies , New Series, Vol. 20, No. 1 (2010), pp. 79-103 https://www.jstor.org/stable/23977728

... of knowledge that can be constantly rearranged, constantly expanded, constantly rebuilt, added to and sorted out. While the topography was fixed in the old systems of knowledge, new categories could easily be set up in the Zettelkasten , for example, under which knowledge found its place that had not been foreseen ...

Paris on the Amazon?: Postcolonial Interrogations of Benjamin’s European Modernism (pp. 216-245) Willi Bolle From: A Companion to the Works of Walter Benjamin, Camden House (2009) Edition: NED - New edition https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7722/j.ctt14brv7g

...and complete but constitutes an open repertoire, always in movement, expressing and stimulating the spirit of experimentation and invention. Let us remember that Benjamin, in his early work Einbahnstraße (One-Way Street, 1923/28), argued in favor of direct communication between the “ Zettelkasten ” (card box...

communication between?! though it is 2009 and after Luhmann's reference to communication with slip boxes....

In Memoriam: Josef Körner (9 May 1950) Robert L. Kahn The Modern Language Review, Vol. 58, No. 1 (Jan., 1963), pp. 38-59 https://www.jstor.org/stable/3720394

...of German letters long before Heine, impudently naive and imprudently honest, though always in- dustrious, 'griindlich' (and was it not Korner who 'discovered' the numerous un- published notebooks of Friedrich Schlegel and, in turn, left behind some twenty ' Zettelkasten ' which were recently acquired by Bonn University, a unique 'Fund-...

example of use of zettelkasten in English here in 1963 specifically as a loan word from German...

On organizational forms of historical research in Germany Hermann Heimpel Historical Journal , Vol. 189 (Dec., 1959), pp. 139-222 https://www.jstor.org/stable/27612563

... , has worked through baroque collectaneas laid out in book form, will appreciate the uniform paper format, the slip box and its prerequisite, the paper cutting machine3). Without the railway there would be no congress?, no ?General Association of German Historical and Antiquity Associations ...

Review: [Untitled] Intellectual history of ancient Christianity by Carl Schneider Review by:Peter Nober Biblica , Vol. 36, No. 4 (1955), pp. 537-539 https://www.jstor.org/stable/42619108

... very different areas, which is all the more astonishing since the author had to endure difficult fates in life at the same time (I, VII: loss of his library and all card boxes in Königsberg). The author has a lot of church history, patristic, archaeological, old classical, rabbinic and even Byzantine literature ...

Der Thesaurus Linguae Latinae in München Adolf Lumpe Journal of Philosophical Research , Vol. 7, H. 1 (1953), pp. 122-125 https://www.jstor.org/stable/20480611

... J. Rubenbauer, Dr. Ida Kap and Dr. O. Hiltbrunner and a large number of domestic and foreign employees. The thesaurus archive, which after various transit stations is now housed in Arcisstrasse (No. 8/III), currently includes around ten million slips of paper in around 7000 slip boxes . So far are complete ...

Review: [Untitled] Richard Dehmel Man and the Thinker; A Biography of His Mind in the Reflection of Time by Harry Slochower Review by:Friedrich Bruns The Journal of English and Germanic Philology, Vol. 30, No. 2 (Apr., 1931), pp. 319-320 https://www.jstor.org/stable/27703515

... who is passionate about this work and who has extensive knowledge, especially in the philosophical field. A restriction must be made. The hardest thing about collecting is throwing it away. Too much is offered to us from a very large slip of paper . From Laotse it goes to John Dewey and from Buddha ...

Review: [Untitled] Historical Records of Rameses III by William F. Edgerton, John A. Wilson Review by: William C. Hayes American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 40, No. 4 (Oct. - Dec., 1936), pp. 558-559

...have been diligently consulted and compared with the present versions and the authors have also availed themselves of the invaluable material contained in the Zettelkasten of the Berlin Wirterbuch der...

This is the oldest appearance of the word "Zettelkasten" appearing in a journal article which I could find on JSTOR.

I'm not surprised it's in a journal in the humanities and specifically on archaeology.

Where is Indiana Jones' zettelkasten?!

Review: [Untitled] Frontier areas of forensic psychology, especially on the theory of legal capacity. (Archive for legal and economic philosophy, vol. 21, pp. 213-219) by Karl Haff Review by:Rümel's Archive for Civilistic Practice , vol. 128, h. 3 (1928), pp. 366-372

... " than with semi-finished products, in which the author's whole list of papers is poured out on the unfortunate reader - quite apart from the cram-books and mnemonics, which still find an all too believing audience. A quote from be in place for Don Quixote ...

Heyde, Johannes Erich. Technik des wissenschaftlichen Arbeitens. (Sektion 1.2 Die Kartei) Junker und Dünnhaupt, 1931.

annotation target: urn:x-pdf:00126394ba28043d68444144cd504562

(Unknown translation from German into English. v1 TK)

The overall title of the work (in English: Technique of Scientific Work) calls immediately to mind the tradition of note taking growing out of the scientific historical methods work of Bernheim and Langlois/Seignobos and even more specifically the description of note taking by Beatrice Webb (1926) who explicitly used the phrase "recipe for scientific note-taking".

see: https://hypothes.is/a/BFWG2Ae1Ee2W1HM7oNTlYg

first reading: 2022-08-23 second reading: 2022-09-22

I suspect that this translation may be from Clemens in German to Scheper and thus potentially from the 1951 edition?

Heyde, Johannes Erich. Technik des wissenschaftlichen Arbeitens; eine Anleitung, besonders für Studierende. 8., Umgearb. Aufl. 1931. Reprint, Berlin: R. Kiepert, 1951.

9/8b2 "Multiple storage" als Notwendigkeit derSpeicherung von komplexen (komplex auszu-wertenden) Informationen.

Seems like from a historical perspective hierarchical databases were more prevalent in the 1960s and relational databases didn't exist until the 1970s. (check references for this historically)

Of course one must consider that within a card index or zettelkasten the ideas of both could have co-existed in essence even if they weren't named as such. Some of the business use cases as early as 1903 (earlier?) would have shown the idea of multiple storage and relational database usage. Beatrice Webb's usage of her notes in a database-like way may have indicated this as well.

9/8b2 "Multiple storage" als Notwendigkeit derSpeicherung von komplexen (komplex auszu-wertenden) Informationen.

9/8b2 "Multiple storage" as a necessity of<br /> storage of complex (complex<br /> evaluating) information.

Fascinating to see the English phrase "multiple storage" pop up in Luhmann's ZKII section on Zettelkasten.

This note is undated, though being in ZKII likely occurred more than a decade after he'd started his practice. One must wonder where he pulled the source for the English phrase rather than using a German one? Does the idea appear in Heyde? It certainly would have been an emerging question within systems theory and potentially computer science ideas which Luhmann would have had access to.

Die vermutlich zwischen 1952 und Anfang 1997 entstandenen Aufzeichnungen, mithilfe derer Luhmann die Ergebnisse seiner exzessiven und interdisziplinär breit angelegten Lektüre systematisch organisiert hat, dokumentieren die Theorieentwicklung auf eine einzigartige Weise, so dass man die Sammlung auch als eine intellektuelle Autobiographie verstehen kann.

The researchers at the Niklas Luhmann-Archive studying Niklas Luhmann's Zettelkasten consider that "the collection can be understood as an intellectual autobiography" (translation mine) even though his slips were generally undated.

Hierbei handelt es sich um eine Sammlung von Notizen, die Luhmann vermutlich zwischen 1952 und 1961 angelegt hat (mit einzelnen späteren Nachträgen; Notizen insbesondere zum Themenkomplex Weltgesellschaft wurden allerdings noch bis ca. 1973 durchweg in diese Sammlung eingestellt). Die insgesamt ca. 23.000 Zettel verteilen sich auf die ersten sieben physischen Auszüge des Kastens sowie auf kleinere Registerabteilungen, die im 17. Auszug der zweiten Sammlung (physischer Auszug 24) stehen. Die Notizen sind im Wesentlichen in der Zeit entstanden, als Luhmann als Rechtsreferendar in Lüneburg bzw. als Regierungsrat im Kultusministerium in Niedersachen gearbeitet hat und dokumentieren seine Lektüre verwaltungs- bzw. staatswissenschaftlicher, philosophischer und zunehmend auch organisationstheoretischer sowie soziologischer Literatur.

According to the Niklas Luhmann-Archiv, Luhmann began his first zettelkasten in 1952 likely when he was working as a legal trainee in Lüneburg or as a government councilor in the Ministry of Education in Lower Saxony.

This timeframe would have been just after Johannes Erich Heyde had published the 8th edition of Technik des wissenschaftlichen Arbeitens in 1951.

Link to: - https://hypothes.is/a/Jn9elsk5Ee2hsLP5WWBEBw on dates of NL ZK - https://hypothes.is/a/CqGhGvchEey6heekrEJ9WA aktenzeichen - https://hypothes.is/a/4wxHdDqeEe2OKGMHXDKezA Clemens Luhmann link

What type of note did Niklas Luhmann average 6 times a day? .t3_11z08fq._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postBodyLink-VisitedLinkColor: #989898; }

reply to u/dotphrasealpha at https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/11z08fq/what_type_of_note_did_niklas_luhmann_average_6/

The true insight you're looking for here is: Forget the numbers and just aim for quality followed very closely by consistency!

Of course most will ignore my insight and experience and be more interested in the numbers, so let's query a the 30+ notes I've got on this topic in my own zettelkasten to answer the distal question.

Over the 45 years from 1952 to 1997 Luhmann produced approximately 90,000 slips which averages out to:

In a video, Ahrens indicates that Luhmann didn't make notes on weekends, and if true, this would revise the count to 7.69 slips per day.

260 working days a year (on average, not accounting for leap years or potential governmental holidays)

Compare these closer numbers to Ahrens' stated and often quoted 6 notes per day in How to Take Smart Notes.

I've counted from the start of '52 through all of '97 to get 45 years, but the true amount of time was a bit shorter than this in reality, so the number of days should be slightly smaller.

Keep in mind that Luhmann worked at this roughly full time for decades, so don't try to measure yourself against him. (He also published in a different era and broadly without the hurdle of peer review.) Again: Aim for quality over quantity! If it helps, S.D. Goitein created a zettelkasten of 27,000 notes which he used to publish almost a third more papers and books than Luhmann. Wittgenstein left far fewer notes and only published one book during his lifetime, but published a lot posthumously and was massively influential. Similarly Roland Barthes had only about 12,500 slips and loads of influential work.

I keep notes on various historical practitioners' notes/day output over several decades using these sorts of practices. Most are in the 1-2 notes per day range. A sampling of them can be found here: https://boffosocko.com/2023/01/14/s-d-goiteins-card-index-or-zettelkasten/#Notes%20per%20day.

Anecdotally, I've found that most of the more serious people here and on the zettelkasten.de forum are in the 4-10 slips per week range.

<whisper>quality...</whisper>

Übersicht über die Auszüge des Zettelkastens Der Zettelkasten Niklas Luhmanns besteht aus insgesamt 27 Auszügen mit jeweils 2500 bis 3500 Zetteln. Diese verteilen sich auf zwei getrennte Zettelsammlungen: Zettelkasten I: 7 Auszüge mit Notizen aus dem Zeitraum von ca. 1952 bis 1961, insgesamt ca. 23.000 Zettel Zettelkasten II: 20 Auszüge mit Notizen aus dem Zeitraum von 1961 bis Anfang 1997, insgesamt ca. 67.000 Zettel. In den Auszügen 15-17 des ZK II, die Teil des hölzernen Zettelkastens sind, sowie den Auszügen 18-20, die außerhalb dieses Kastens in einzelnen Schubern gelagert waren, befinden sich die bibliographischen Abteilungen des ZK II. Teil des Auszugs 17 sind zudem mehrere Schlagwortregister und ein Personenregister des ZK II sowie einige weitere Spezialabteilungen, außerdem das Schlagwortregister sowie die bibliographische Abteilung und eine Themenübersicht des ZK I.

Niklas Luhmann's zettelkasten consists of a total of 27 sections/drawers each containing from 2,500 to 3,500 slips.

Sections 15, 16, 17 were part of the beechwood zettelkasten and along with sections 18, 19, and 20 which were stored outside of the main boxes in individual slipcases contain the bibliographic portions of ZKII

Part of section 17 contains some of the index as well as an index of people for ZKII in addition to some other special portions along with the index of keywords, bibliographical slips, and an overview of topics from ZKI.

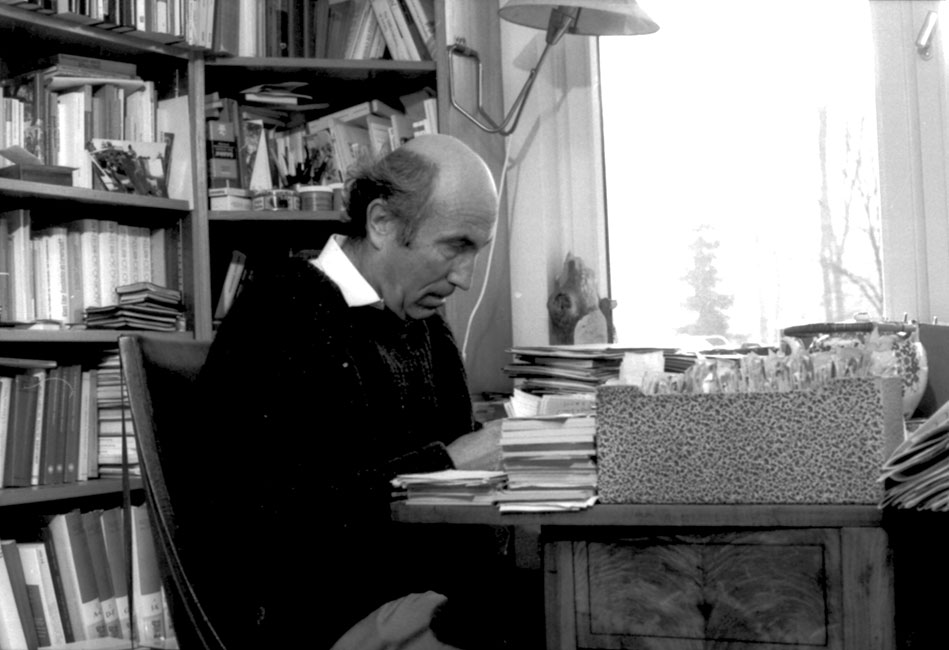

The primary wooden boxes frequently pictured as "Luhmann's zettelkasten" is comprised of six wooden four-drawer card index filing cabinets which were supplemented by three individual slipcases.

One would suspect the individual slipcases were like the one pictured on his desk here:

Luhmann zuhause am Zettelkasten (vermutlich Ende der 1970er/Anfang 1980er Jahre)<br />

Copyright Michael Wiegert-Wegener<br />

via Niklas Luhmann Online: die Erschließung seines Nachlasses - Geistes- & Sozialwissenschaften

Luhmann zuhause am Zettelkasten (vermutlich Ende der 1970er/Anfang 1980er Jahre)<br />

Copyright Michael Wiegert-Wegener<br />

via Niklas Luhmann Online: die Erschließung seines Nachlasses - Geistes- & Sozialwissenschaften

The Luhmann archive has a photo of the beechwood portion with 24 drawers and one of the additional slipboxes on top of it:

(via https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/nachlass/zettelkasten)

(via https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/nachlass/zettelkasten)

Most of the photos from the museum exhibition and elsewhere only focus on or include the main wooden portion of six cabinets with the 24 drawers.

See also: https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/nachlass/zettelkasten

Over the 45 years from 1952 to 1997 this production of approximately 90,000 slips averages out to

45 years * 365 days/year = 16,425 days 90,000 slips / 16,425 days = 5.47 slips per day.

260 working days a year (on average, not accounting for leap years or potential governmental holidays) 45 years x 260 work days/year = 11,700 90,000 slips / 11,700 days = 7.69 slips per day

In a video, Ahrens indicates that Luhmann didn't make notes on weekends, and if true this would revise the count to 7.69 slips per day.

Compare these closer numbers to Ahrens' stated 6 notes per day in How to Take Smart Notes. <br /> See: https://hypothes.is/a/iwrV8hkwEe2vMSdjnwKHXw

I've counted from the start of '52 through all of '97 to get 45 years, but the true amount of time was a bit shorter than this in reality, so the number of days should be slightly smaller.

Since Luhmann’s system of the slip box is well-known, Ahrens’ valuable contribution lies less in providing an innovative technique of note-taking and the organization of academic writing, but more in reflecting critically on the very nature of writing as a medium of knowledge generation.

I think that by saying "Luhmann's system of the slip box is well-known", Stephanie Schiller is not talking about his specific box or his specific method, but the broader rhetorical method of the ars excerpendi and note taking in general. There isn't a whole lot of evidence to indicate that, except for a small segment of sociologists who may have know his work, that Luhmann's slip box was specifically well known at all up to the point of Ahrens' book.

https://www.ebay.com/itm/155447667554

This Catalog has a page with the various sizes of card catalog boxes available from Cole Steel in 1950s. The external sizes can be useful for placing the individual card sizes for some of these boxes on the secondary market.

They also include approximate card capacities.

If I have many notes, is it more effective to load into chapters, or into ZK, organise, then load into chapters? .t3_11xcnqg._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postBodyLink-VisitedLinkColor: #989898; }

reply to u/jaybestnz https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/11xcnqg/if_i_have_many_notes_is_it_more_effective_to_load/

Part of the benefit of having a Luhmann-esque structured ZK, which is what I'm presuming your definition of a zettelkasten is, is that you're doing some of the interconnecting and building links and structures along the way. Instead, you'll now be doing that work after the fact and en-masse.

The underlying question is: do you plan on keeping and maintaining a more Luhmann-esque zettelkasten after your book? If you do, then it may be useful to take that step, otherwise, you're likely doing additional work that you may not see benefit from.

Making some broad assumptions about what you may have so far... If you've got physical index cards, things will be easier to collate and arrange. In your case, the closest (easy) workflow is that of Ryan Holiday who outlines his process in this video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dU7efgGEOgk

Beyond this, your next best bets might be informed by:

If you prefer your writing structural advice in written form, then perhaps you're already in the latter part of the process broadly described by Umberto Eco in How to Write a Thesis (MIT, 2015).

I find that last claim highly unlikely. If you walk through a bog, you get bogged down. That's where the phrase comes from, Magnus.

In re: Last lines of: https://www.nb.admin.ch/snl/en/home/about-us/sla/insights-outlooks/einsichten---aussichten-2012/aus-dem-nachlass-von-james-peter-zollinger.html

Google translate does a reasonable job on translating it as 'getting bogged down' but the original sich ‹verzettelt› would mean roughly to "get lost in the slips", perhaps in a way similar to Anatole France's novel Penguin Island (L’Île des Pingouins. Calmann-Lévy, 1908) but without the storm or the death.

A native and bi-lingual German speaker might be better at explaining it, but this is a useful explanation of the prefix (sich) ver- : https://yourdailygerman.com/german-prefix-ver-meaning/

https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/11uibsm/zettelkasten_or_hopeless_paper_chaos/

I guess a collection of notes is now a zettelkasten.

Don't be blinded by availability bias. It was historically almost always thus! Especially in Germany. (The French have traditionally called it a fichier boîte and in English it's the card index.) It's only been since the rise in popularity of the use of the German word in English (beginning in late 2013 with zettelkasten.de) where it has almost always been associated with Niklas Luhmann that has has most people now associating Luhmann's method with the word Zettelkasten.

If you look back at the 2013 exhibition "Zettelkästen. Machines of Fantasy" at the Museum of Modern Literature, Marbach am Neckar, you'll notice that there were six zettelkasten featured there including those of Arno Schmidt, Walter Kempowski, Friedrich Kittler, Aby Warburg, Paul, Blumenberg, and Luhmann. Of those, the structure of Luhmann's was the exception which wasn't primarily organized broadly by subject heading. You'll also find some historians and sociologists organizing theirs by date or geographic regions as well as other custom arrangements as their needs and work might dictate.

The preponderance of books talking about these note taking methods suggest a topic heading arrangement for filing, including the book by Johnannes Erich Heyde from which Luhmann's son has indicated he learned an old technique from which he evolved his own practice.

See also:

The Two Definitions of Zettelkasten https://boffosocko.com/2022/10/22/the-two-definitions-of-zettelkasten/

Heyde, Johannes Erich. Technik des wissenschaftlichen Arbeitens: zeitgemässe Mittel und Verfahrungsweisen. Junker und Dünnhaupt, 1931.

Rarely does a week go by that I don't run across another new/significant example of a zettelkasten. Thanks u/atomicnotes for keeping up the pace with James Peter Zollinger. (Though this week may be a twofer given my notes on Ludwig Wittgenstein's over the last few days.)

Aus dem Nachlass von James Peter Zollinger<br /> Swiss National Library NL

ᔥ u/atomicnotes in r/Zettelkasten - Zettelkasten, or "hopeless paper chaos"? <br /> (accessed:: 2023-03-20 04:49:15)

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Zettel. Edited by Gertrude Elizabeth Margaret Anscombe and Georg Henrik von Wright,. Translated by G. E. M. Anscombe. Second California Paperback Printing. 1967. Reprint, Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press, 2007.

annotation target: urn:x-pdf:15f4a1e48274f28b55eb6f8411c1ff1c

After most of the typed fragments had been traced to theirsources, comparison of them with their original forms, togetherwith certain physical features, shewed clearly that Wittgensteindid not merely keep these fragments, but worked on them,altered and polished them in their cut-up condition. This sug-gested that the addition of separate MS pieces to the box wascalculated; the whole collection had a quite different characterfrom the various bundles of more or less 'stray' bits of writingwhich were also among his Nachlass.

We were naturally at first rather puzzled to account for thisbox. Were its contents an accidental collection of left-overs?Was it a receptacle for random deposits of casual scraps ofwriting? Should the large works which were some of its sourcesbe published and it be left on one side?

This section makes me question whether or not the editors of this work were aware of the zettelkasten tradition?!?

Often fragments on the same topic were clipped together; butthere were also a large number lying loose in the box. Someyears ago Peter Geach made an arrangement of this material,keeping together what were in single bundles, and otherwisefitting the pieces as well as he could according to subject matter.This arrangement we have retained with a very few alterations

This brings up the question of how Ludwig Wittgenstein arranged his own zettelkasten...

Peter Geach made an arrangement of Wittgenstein's zettels which was broadly kept in the edited and published version Zettel (1967). Apparently fragments on the same topic were clipped together indicating that Wittgenstein's method was most likely by topical headings. However there were also a large number of slips "lying loose in the box." Perhaps these were notes which he had yet to file or which some intervening archivist may have re-arranged?

In any case, Geach otherwise arranged all the materials as best as he could according to subject matter. As a result the printed book version isn't necessarily the arrangement that Wittgenstein would have made, but the editors of the book felt that at least Geach's arrangement made it an "instructive and readable compilation".

This source doesn't indicate the use of alphabetical dividers or other tabbed divisions.

The earliest time of composition of any of these fragmentswas, so far as we can judge, 1929. The date at which the latestdatable fragment was written was August 1948. By far thegreatest number came from typescripts which were dictated from1945- 1948

Based on the dating provided by Anscombe and von Wright, Wittgenstein's zettelkasten slips dated from 1929 to 1948.

for reference LW's dates were 1889-1951

Supposing that the notes preceded the typescripts and not the other way around as Anscombe and von Wright indicate, the majority of the notes were turned into written work (typescripts) which were dictated from 1945-1948.

What was LW's process? Note taking, arranging/outlining, and then dictation followed by editing? Dictating would have been easier/faster certainly if he'd already written down his cards and could simply read from them to a secretary.

Others again were in manuscript,apparently written to add to the remarks on a particular matterpreserved in the box.

Some of the manuscript notes in Wittgenstein's zettelkasten were "apparently written to add to the remarks on a particular matter preserved in the box".ᔥ So much like Niklas Luhmann's wooden conversation partner, Wittgenstein was not only having conversations with the texts he was reading, he was creating a conversation between himself and his pre-existing notes thus extending his lines of thought within his zettelkasten.

. They were for the most partcut from extensive typescripts of his, other copies of which stillexist. Some few were cut from typescripts which we have notbeen able to trace and which it is likely that he destroyed but forthe bits that he put in the box.

In Zettel, the editors indicate that many of Wittgenstein's zettels "were for the most part cut from extensive typescripts of his, other copies of which still exist." Perhaps not knowing of the commonplace book or zettelkasten traditions, they may have mistook the notes in his zettelkasten as having originated in his typescripts rather than them having originated as notes which then later made it into his typescripts!

What in particular about the originals may have made them think it was typescript to zettel?

WB publish here a collection of fragments made by Wittgensteinhimself and left by him in a box-file

In 1967, G. E. M. Anscombe and G. H. von Wright published a collection of notes from Ludwig Wittgenstein's zettelkasten which they aptly titled Zettel.

"Personal Knowledge Management Is Bullshit"

reply to jameslongley at https://forum.zettelkasten.de/discussion/2532/personal-knowledge-management-is-bullshit

I find that these sorts of articles against the variety of practices have one thing in common: the writer fails to state a solid and realistic reason for why they got into it in the first place. They either have no reason "why" or, perhaps, just as often have all-the-reasons "why", which may be worse. Much of this is bound up in the sort of signaling and consumption which @Sascha outlines in point C (above).

Perhaps of interest, there are a large number of Hypothes.is annotations on that original article written by a variety of sense-makers with whom I am familiar. See: https://via.hypothes.is/https://www.otherlife.co/pkm/ Of note, many come from various note making traditions including: commonplace books, bloggers, writers, wiki creators, zettelkasten, digital gardening, writers, thinkers, etc., so they give a broader and relatively diverse perspective. If I were pressed to say what most of them have in common philosophically, I'd say it was ownership of their thought.

Perhaps it's just a point of anecdotal evidence, but I've been noticing that who write about or use the phrase "personal knowledge management" are ones who come at the space without an actual practice or point of view on what they're doing and why—they are either (trying to be) influencers or influencees.

Fortunately it is entirely possible to "fake it until you make it" here, but it helps to have an idea of what you're trying to make.

Don't Dehorsify the Horse<br /> by Sasha Fast

If someone tells you that your Zettelkasten is not a Zettelkasten, just refer him to the late Wittgenstein and send him a three-legged horse. It might not solve the issue but bring some peace to your mind.

Perhaps apropos from Wittgenstein's own zettelkasten? 🐎

- ''Putting the cart before the horse" may be said of an explanation like the following: we tend someone else because by analogy with our own case we believe that he is experiencing pain too.—Instead of saying: Get to know a new aspect from this special chapter of human behaviour—from this use of language. (p96)

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Zettel. Edited by Gertrude Elizabeth Margaret Anscombe and Georg Henrik von Wright,. Translated by G. E. M. Anscombe. Second California Paperback Printing. 1967. Reprint, Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press, 2007.

the very point of a Zettelkasten is to ditch the categories.

If we believe as previously indicated by Luhmann's son that Luhmann learned the basics of his evolved method from Johannes Erich Heyde, then the point of the original was all about categories and subject headings. It ultimately became something which Luhmann minimized, perhaps in part for the relationship of work and the cost of hiring assistants to do this additional manual labor.

The Zettelkasten Method seems to get more and more popular. With popularity of methods there always comes a problem: Overzealous Orthodoxy. Some people, for various reasons, try to state what a Zettelkasten is and what not.

The hilarious part of this is that within a much broader tradition of Western intellectual history, Niklas Luhmann's zettelkasten is one of the most heterodox approaches on the map.

https://www.indiamart.com/proddetail/charging-tray-for-library-readers-tickets-14436111112.html

A wooden 5 tray charging tray with lid! This could make a fascinating portable zettelkasten. It has options for both 2"x3" and 3"x5"Cards.

Brodart Full-Length Single Charging Tray<br /> Full- length charging tray with 1,000-card capacity<br /> Price: $96.32

See also: https://hypothes.is/a/ao89RMQmEe2zIvsu3lf6kw for a smaller version

Brodart Mini Single Charging Tray Mini single charging tray with 600-card capacity More Info Price: $76.76

This could be used for a modern day Memindex box for portrait oriented 3 x 5" index cards.

Einblicke in das System der Zettel - Geheimnis um Niklas Luhmanns Zettelkasten, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4veq2i3teVk.

Watched 2023-03-13

Mentioned elsewhere, but there's a segment here that he used whatever paper he happened to have around including the receipts from a brewery, tax papers, and even his children's art papers.

In der aktuellen Folge „research_tv“ der Universität Bielefeld erklären Professor Dr. André Kieserling, Johannes Schmidt und Martin Löning, wie sie sich der so genannten „intellektuellen Autobiographie“ Luhmanns annähern.

Translation:

In the current episode "research_tv" of Bielefeld University, Professor Dr. André Kieserling, Johannes Schmidt and Martin Löning how they approach Luhmann's so-called “intellectual autobiography”.

!!

Commenting can take many forms in your notes.

The issue is that most of times it is states like this, but almost every writer in the PKM and zettelkasten world do not provide a example as a model, so no one knows for sure if it is well commented or not.

The AdlerNet Guide, Part III<br /> by Amy Hunt

Scott Scheper has popularized a numbering scheme based on Wikipedia's Outline of Academic Disciplines.

It's not just me who's noticed this.

Interesting that for someone propounding Luhmann's zettelkasten system that Scheper has done this. Was it because he did it himself and then didn't want to change (likely) or because he spent time seeing others' problems with Luhmann's numbering system and designed a better way (less likely)?

Simon Winchester describes the pigeonhole and slip system that professor James Murray used to create the Oxford English Dictionary. The editors essentially put out a call to readers to note down interesting every day words they found in their reading along with examples sentences and references. They then collected these words alphabetically into pigeonholes and from here were able to collectively compile their magisterial dictionary.

Interesting method of finding example sentences in words.

A zettelkasten with no quotes—by definition—shouldn’t carry the name. So let’s lay to rest that dreadful idea that quotes aren’t allowed in a zettelkasten.

This is fundamental. No research project has no quotes. Sometimes the words of the author is just better than anything that one could say.

The width of the drawers of both McDowell & Craig and Steelcase desks is just wide enough to accommodate two rows of 4 x 6" index cards side by side with enough space that one might insert a sizeable, but thin divider between them

I suspect that this is a specific design choice in a world in which card indexes often featured in the office environment of the mid-twenty first century.

Were other manufacturers so inclined to do this? Is there any evidence that this was by design? Did people use it for this? Was there a standard drawer width?

The metal inserts to section off the desk drawer area could have also been used for this sort of purpose and had cut outs to allow for expanding and contracting the interior space.

Keep in mind that some of these tanker desks were also manufactured with specific spaces or areas intended for typewriters or for storing them.

https://www.garten-des-gedenkens.de/?page_id=118&lang=EN

Example of a zettelkasten as an Holocaust rememberance/momument installation in Marburg in 2012

http://tamaroszettelkasten.blogspot.com/

Example of a blog being kept as a zettelkasten....

Altfranzösisches etymologisches Wörterbuch : AGATE

I recall that the Oxford English Dictionary was also compiled using a slip box method of sorts, and more interestingly it was a group effort.

Similarly Wordnik is using Hypothes.is to recreate these sorts of patterns for collecting words in context on digital cards.

Many encyclopedias followed this pattern as did Adler's Syntopicon.

Not sure why Manfred Kuehn removed this website from Blogger, but it's sure to be chock full of interesting discussions and details on his note taking process and practice. Definitely worth delving back several years and mining his repository of articles here.

http://takingnotenow.blogspot.com/<br /> archive: https://web.archive.org/web/20230000000000*/http://takingnotenow.blogspot.com/

OurNew "400"SeriesNo.400(likecut)hasdeepdrawerarrangedwithVERTICALFILINGEQUIPMENT,writingbednotbrokenbytypewriter,whichdisappearsindust-proofcompartment.GUNNDESKSaremadein250differentpatterns,inallwoodsandfinishes,fittedwith ourtimesavingDROP-FRONTPigeonholebox.Ifyoudesireanup-to-datedeskofanydescriptionandbestpossiblevalueforyourmoneygetaGunn.Ourreference-TheUser-TheManwiththeGunn."Soldbyallleadingdealersorshippeddirectfrom thefactory.Sendforcatalogueof desksandfilingdevices-mailedFREE."AwardedGoldMedal,World'sFair,St.Louis."GUNNFURNITURECO.,GrandRapids,Mich.MakersofGunnSec-tionalBookCases

Gunn Desks and filing cabinets

Example advertisement of a wooden office desk with pigeonholes and a small card index box on the desktop as well as a drawer pull with a typewriter sitting on it.

Federal Steel FixtureCompany

Federal Steel Fixture Company manufactured a variety of steel office furniture including desks, cabinets, lockers, filing cabinets, shelving, and card cabinets.

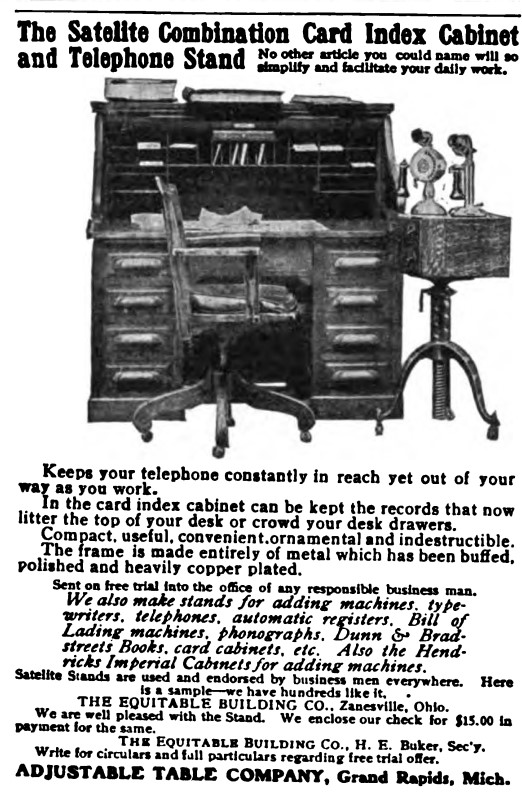

TheSateliteCombinationCard IndexCabinetandTelephoneStand

A fascinating combination of office furniture types in 1906!

The Adjustable Table Company of Grand Rapids, Michigan manufactured a combination table for both telephones and index cards. It was designed as an accessory to be stood next to one's desk to accommodate a telephone at the beginning of the telephone era and also served as storage for one's card index.

Given the broad business-based use of the card index at the time and the newness of the telephone, this piece of furniture likely was not designed as an early proto-rolodex, though it certainly could have been (and very well may have likely been) used as such in practice.

I totally want one of these as a side table for my couch/reading chair for both storing index cards and as a temporary writing surface while reading!

This could also be an early precursor to Twitter!

Folks have certainly mentioned other incarnations: - annotations in books (person to self), - postcards (person to person), - the telegraph (person to person and possibly to others by personal communication or newspaper distribution)

but this is the first version of short note user interface for both creation, storage, and distribution by means of electrical transmission (via telephone) with a bigger network (still person to person, but with potential for easy/cheap distribution to more than a single person)

You need to be on top of your index. This is your main navigation system.

This is a major drawback to this method and the affordance of sparse indexing using Luhmann's method.

It was easier said than done to know when to add punctuation like / or .

Example of someone who doesn't seem to understand that the / or . are primarily for readability.

The ‘top level’ category was too fixed, and it was hard to know when you needed a new category i.e. 1004 versus 1003/3.

The problem here is equating the "top level" number with category in the first place. It's just an idea and the number is a location. Start by separating the two.

https://www.ebay.com/itm/364064561931 Vintage The CE Ward Co. Wood Index Card File Box HTF

The state of current technology greatly impacts our ability to manipulate information, which in turn exerts influence on our ability to develop new ideas and technologies. Tools designed to enable networked thinking are a step in the direction of Douglas Engelbart’s vision of augmenting the human intellect, resulting in “more-rapid comprehension, better comprehension, the possibility of gaining a useful degree of comprehension in a situation that previously was too complex, speedier solutions, better solutions, and the possibility of finding solutions to problems that before seemed insolvable.”

There's a danger to using digital tools to help with Higher Order Thinking; namely, it offloads precious cognitive load, optimized intrinsic load, which is used to build schemas and structural knowledge which is essential for mastery. Another danger is that digital tools often make falling for the collector's fallacy easier, meaning that you horde and horde information, which makes you think you have knowledge, while in fact, you simply have (maybe related) information, not mastery. The analog way prevents this, as it forces you to carefully evaluate the value of an idea and decide whether or not it's worth it to spend time on writing it and integrating it into a line of thought. Evaluation/Analysis is forced in an analog networked thinking tool, which is a form of Higher Order Learning/Thinking, as they are in the higher orders of Bloom's Taxonomy/Hierarchy.

This is also true for AI. Always carefully evaluate whether or not a tool is worth using, like a farmer. (Deep Work, Cal Newport).

Instead, use a tool like mindmapping, the GRINDE way, which is digital, for learning... Or the Antinet Zettelkasten by Scott Scheper, which is analog, for research.

Divergence and emergence allow networked thinkers to uncover non-obvious interconnections and explore second-order consequences of seemingly isolated phenomena. Because it relies on undirected exploration, networked thinking allows us to go beyond common sense solutions.

The power of an Antinet Zettelkasten. Use this principle both in research and learning.

While I love a great notebook as much as (more than?) the next person, a lot of the notes I take are specifically for filing into either my zettelkasten or index card-based commonplace book for later re-use. Sadly there's not a lot out there in the 4 x 6" format, so I've been able to use some book binder's glue to fashion my own "index card notebooks" which are dissemble-able for filing into my card files for cross indexing. The best part is that I can choose the paper and what's printed on it (blank, lined, grid, etc.) for use with my favorite writing media including fountain pens. I've been doing this for a while and it's working out pretty well. More details: https://boffosocko.com/2022/12/01/index-card-accessories-for-note-taking-on-the-go/

Custom made notebook comprised of 4 x 6" index cards glued at the top with book adhesive surrounded by the binder clips and Lineco glue and paint brush used to make/bind the notebook. Arrayed around the "notebook" are a Lochby pen wallet and carrying case.

I've recently begun adding a chipboard backing to have a firmer writing surface while on the go as well as for inserting into a custom made journal cover/case/wallet in the future, though I've yet to find something off-the-shelf for this. Maybe an A6 cover with some extra margin for error in the size difference?

Has anyone else done this? Suggestions for improvement?

Understanding Zettelkasten notes <br /> by Mitch (@sacredkarailee@me.dm) 2022-02-11

Quick one pager overview which actually presumes you've got some experience with the general idea. Interestingly it completely leaves out the idea of having an index!

Otherwise, generally: meh. Takes a very Ahrens-esque viewpoint and phraseology.

The date and time (YYYYMMDD hhmm) form a unique identifier for the note. As I get it using this unique identifier is a way to make the notes "anonymous" so that "surprise" connections between them can be found that we wouldn't otherwise have noticed. In other words, it removes us from getting in our own way and forcing the notes to connect in a certain way by how we name them. A great introduction to the system can be found at zettelkasten.de. The page is written in English. The origional numbering system is discussed in the article. The modern computerized system uses the date and time as the unique identifier. I hope this helps.

reply to u/OldSkoolVFX at https://www.reddit.com/r/ObsidianMD/comments/11jiein/comment/jb6np3f/?utm_source=reddit&utm_medium=web2x&context=3

I've studied (and used) Luhmann and other related systems more closely than most, so I'm aware of zettelkasten.de and the variety of numbering systems available including how Luhmann's likely grew out of governmental conscription numbers in 1770s Vienna. As a result your answer comes close to a generic answer, but not to the level of specificity I was hoping for. (Others who use a timestamp should feel free to chime in here as well.)

How specifically does the anonymity of the notes identified this way create surprise for you? Can you give me an example and how it worked for you?

As an example in my own practice using unique titles in Obsidian, when I type [[ and begin typing a word, I'll often get a list of other notes which are often closely related. This provides a variety of potential links and additional context to which I can write the current note in light of. I also get this same sort of serendipity in the autocomplete functionality of my tagging system which has been incredibly useful and generative to me in the past. This helps me to resurface past notes I hadn't thought of recently and can provide new avenues of growth and expansion.