- Jul 2023

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

Hello! I've recently encountered the Zettelkasten system and adore the emphasis on connecting ideas. However, I don't want to use the traditional index card way, seeing as I have a ring binder with 90 empty pages thus I don't want it to go to waste. I've researched a lot of methods using a notebook, where some organize their zettels by page number, while others write as usual and connect and index the ideas for every 30 pages or so. But considering that the loose-leaf paper can be in any order I chose, I think there can be a better workaround there. Any suggestions? Thanks in advance!

reply to u/SnooPandas3432 at https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/158tzk7/zettelkasten_on_a_ring_binder_with_looseleaf_paper/

She didn't specify a particular dimension, but I recall that Beatrice Webb used larger sheets of paper than traditional index-card sized slips in her practice and likely filed them into something akin to hanging files in a filing cabinet.

For students, I might suggest using the larger sheets/3-ring binder to make Cornell notes for coursework and then later distilling down one or two of the best ideas from a lecture or related readings into index card form for filing away over time. You could then have a repository of bigger formatted literature notes from books/lectures with more space and still have all the benefits of a more traditional card-based zettelkasten for creativity and writing. You could then have the benefit of questions for spaced repetition for quizzes/tests, while still keeping bigger ideas for writing papers or future research needs.

-

-

blog.ayjay.org blog.ayjay.org

-

https://blog.ayjay.org/unanswered-questions/

The index-card based notes pictured in this post certainly makes me think that Alan Jacobs has the sort of note taking/commonplace book sort of practice I thought he would.

-

-

www.nytimes.com www.nytimes.com

-

About 24 percent of Italians are over 65, making it the oldest country in Europe, and over 4 million of them live alone.

24% of Italy's population is roughly 14 million people.

So there are 14 million people over 65 in Italy.

If 4 million of them live alone, that is approximately 28%.

This is as of 7/21/23

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

Overloaded with notes .t3_15218d5._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postBodyLink-VisitedLinkColor: #989898; } A few years ago I moved from Evernote to Obsidian. Evernote had this cool web clipper feature that helped me gather literary quotes, tweets, Wikipedia facts, interview bits, and any kinds of texts all around the web. And now I have a vault with 10k notes.I am trying to review a few every time I open Obsidian (add tags, link it, or delete) but it is still too much.Did someone have the same experience? How did you manage to fix everything and move to a bit more controllable system (zettelkasten or any other)?Cus I feel like I am standing in front of a text tsunami

reply to u/posh-and-repressed at https://www.reddit.com/r/ObsidianMD/comments/15218d5/overloaded_with_notes/

Overwhelm of notes always reminds me of this note taking story from 1908: https://boffosocko.com/2022/10/24/death-by-zettelkasten/ If you've not sorted them, tagged/categorized them or other, then search is really your only recourse. One of the benefits of Luhmann's particular structure is that it nudged him to read and review through older cards as he worked and filed new ones. Those with commonplace books would have occasionally picked up their notebooks and paged through them from time to time. Digital methods like Obsidian don't always do a good job of allowing or even forcing this review work on the user, so you may want to look at synthetic means like one of the random note plugins. Otherwise don't worry too much. Fix your tagging/categorizing/indexing now so that things slowly improve in the future. (I'm sitting on a pile of over 50K notes without the worry of overwhelm, primarily as I've managed to figure out how to rely on my index and search.)

-

-

-

But I would do less than justice to Mr. Adler's achieve-ment if I left the matter there. The Syntopicon is, in additionto all this, and in addition to being a monument to the indus-try, devotion, and intelligence of Mr. Adler and his staff, astep forward in the thought of the West. It indicates wherewe are: where the agreements and disagreements lie; wherethe problems are; where the work has to be done. It thushelps to keep us from wasting our time through misunder-standing and points to the issues that must be attacked.When the history of the intellectual life of this century iswritten, the Syntopicon will be regarded as one of the land-marks in it.

p xxvi

Hutchins closes his preface to his grand project with Mortimer J. Adler by giving pride of place to Adler's Syntopicon.

Adler's Syntopicon isn't just an index compiled into two books which were volumes 2 and 3 of The Great Books of the Western World, it's physically a topically indexed card index of data (a grand zettelkasten surveying Western culture if you will). It's value to readers and users is immeasurable and it stands as a fascinating example of what a well-constructed card index might allow one to do even when they don't have their own yet.

Adler spoke of practicing syntopical reading, but anyone who compiles their own card index (in either analog or digital form) will realize the ultimate value in creating their own syntopical writing or what Robert Hutchins calls participating in "The Great Conversation" across twenty-five centuries of documented human communication.

See also: https://hypothes.is/a/WF4THtUNEe2dZTdlQCbmXw

The way Hutchins presents the idea of "Adler's achievement" here seems to indicate that Hutchins didn't have a direct hand in compiling or working on it directly.

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

Converting Commonplace Books? .t3_14v2ohz._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postBodyLink-VisitedLinkColor: #989898; }

reply to u/ihaveascone at https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/14v2ohz/converting_commonplace_books/

Don't convert unless you absolutely need to, it will be a lot of soul-crushing make work. Since some of your practice already looks like Ross Ashby's system, why not just continue what you've been doing all along and start a physical index card-based index for your commonplaces? (As opposed to a more classical Lockian index.) As you browse your commonplaces create index cards for topics you find and write down the associated book/page numbers. Over time you'll more quickly make your commonplace books more valuable while still continuing on as you always have without skipping much a beat or attempting to convert over your entire system. Alternately you could do a paper notebook with a digital index too. I came across https://www.indxd.ink, a digital, web-based index tool for your analog notebooks. Ostensibly allows one to digitally index their paper notebooks (page numbers optional). It emails you weekly text updates, so you've got a back up of your data if the site/service disappears. This could potentially be used by those who have analog commonplace/zettelkasten practices, but want the digital search and some back up of their system.

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

Inserting a maincards with lack of memory .t3_14ot4na._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postBodyLink-VisitedLinkColor: #989898; } Lihmann's system of inserting a maincard is fundamentally based on a person's ability to remember there are other maincards already inserted that would be related to the card you want to insert.What if you have very poor memory like many people do, what is your process of inserting maincards?In my Antinet I handled it in an enhanced method from what I did in my 27 yrs of research notebooks which is very different then Lihmann's method.

reply to u/drogers8 at https://www.reddit.com/r/antinet/comments/14ot4na/inserting_a_maincards_with_lack_of_memory/

I would submit that your first sentence is wildly false.

What topic(s) cover your newly made cards? Look those up in your index and find where those potentially related cards are (whether you remember them or not). Go to that top level card listed in your index and see what's there or in the section of cards that come after it. Find the best card in that branch and file your new card(s) as appropriate. If necessary, cross-index them with sub-topics in your index to make them more findable in the future. If you don't find one or more of those topics in your index, then create a new branch and start an index entry for one or more of those terms. (You'll find yourself making lots of index entries to start, but it will eventually slow down—though it shouldn't stop—as your collection grows.)

Ideally, with regular use, you'll likely remember more and more, especially for active areas you're really interested in. However, take comfort that the system is designed to let you forget everything! This forgetting will actually help create future surprise as well as serendipity that will actually be beneficial for potentially generating new ideas as you use (and review) your notes.

And if you don't believe me, consider that Alberto Cevolini edited an entire book, broadly about these techniques—including an entire chapter on Luhmann—, which he aptly named Forgetting Machines!

-

-

Local file Local file

-

Webb, Beatrice P. (1926). My Apprenticeship. Longmans, Green & Co.

urn:x-pdf:d46f7c2791538c32a5ef76b13cdb9fe8

https://hypothes.is/users/chrisaldrich?q=urn%3Ax-pdf%3Ad46f7c2791538c32a5ef76b13cdb9fe8

Available at archive.org: https://archive.org/details/myapprenticeship0000beat/page/n7/mode/2up

-

- Jun 2023

-

docdrop.org docdrop.org

-

As indicated in the analysis of the tune, the A section of “Confirmation” contains elementsof the blues, such as single blue-note inflections and characteristic blues harmonies

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

What I love and appreciate from Metivier, he will cite his sources. He makes it super easy to go back to his sources and mine those materials myself. He gives credit to other memory experts and is transparent throughout his books and course about where he is in his own process of growing and learning. In summary, we don't need originality, we need what works and in the scholarly world- syncretizing multiple sources and distilling them into a process IS original even if every building block is coming from another source. We're all standing on the shoulders of the giants before us.

My note-taking method is informed by the commonplace book and zettelkasten: why reinvent a wheel that needs no reinventing (it is only, really, about translating things from one medium to another)

-

I just can't get into these sort of high-ritual triage approaches to note-taking. I can admire it from afar, which I do, but find this sort of "consider this ahead of time before you make a move" approaches to really drag down my process.But, I do appreciate them from a sort of "aesthetics of academia" perspective.

Reply to Bob Doto at https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/14ikfsy/comment/jplo3j2/?utm_source=reddit&utm_medium=web2x&context=3 with respect to PZ Compass Points.

I'll agree wholeheartedly that applying methods like this to each note one takes is a "make work" exercise. It's apt to encourage people into the completist trap of turning every note they take into some sort of pristine so-called permanent or evergreen note, and there are already too many of those practitioners, who often give up in a few weeks wondering "where did I go wrong?".

It's useful to know that these methods and tools exist, particularly for younger students, but I would never recommend that one apply them on a daily or even weekly basis. Maybe if one was having trouble with a particular idea or thought and wanted to more exhaustively explore the adjacent space around it, but even here going out for a walk in nature and allowing diffuse thinking to do some of the work is likely to be just as (maybe more?) productive.

It could be the sort of thing to write down in your collection of Oblique Strategies to pull out when you're hitting a wall?

-

-

translate.google.com translate.google.com

-

https://translate.google.com/?sl=ja&tl=en&text=%E6%B3%A8&op=translate

注 (Chū), Japanese for note

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

According to Henderson, there are three steps to keeping a commonplace book:

1) Read (Consume)

"Commonplace books begin with observation."

2) Capture (Write) Always also capture the source.

3) Reflect Write own thoughts about the material. Synthesize, think.

I'd personally use a digital commonplace book (hypothes.is), like Chris Aldrich explains, as my capture method and my Antinet Zettelkasten as my reflect methodology. This way the commonplace book fosters what Luhmann would call the thought rumination process.

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

A commonplace book, according to Jared Henderson, is a way to not collect own thoughts (though sometimes it is) but rather to collect thoughts by others that you deem interesting.

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

(1:21:20-1:39:40) Chris Aldrich describes his hypothes.is to Zettelkasten workflow. Prevents Collector's Fallacy, still allows to collect a lot. Open Bucket vs. Closed Bucket. Aldrich mentions he uses a common place book using hypothes.is which is where all his interesting highlights and annotations go to, unfiltered, but adequately tagged. This allows him to easily find his material whenever necessary in the future. These are digital. Then the best of the best material that he's interested in and works with (in a project or writing sense?) will go into his Zettelkasten and become fully fledged. This allows to maintain a high gold to mud (signal to noise) ratio for the Zettelkasten. In addition, Aldrich mentions that his ZK is more of his own thoughts and reflections whilst the commonplace book is more of other people's thoughts.

-

-

www.uclaextension.edu www.uclaextension.edu

-

Nick Milo is offering a remote digital note taking and writing course for $485 for UCLA Extension in late summer 2023.

Nick Milodragovich

-

-

www.gutenberg.org www.gutenberg.org

-

I would advise you to read with a pen in your hand, and enter in a little book short hints of what you find that is curious or that may be useful; for this will be the best method of imprinting such particulars in your memory, where they will be ready either for practice on some future occasion if they are matters of utility, or at least to adorn and improve your conversation if they are rather points of curiosity.

Benjamin Franklin letter to Miss Stevenson, Wanstead. Craven-street, May 16, 1760.

Franklin doesn't use the word commonplace book here, but is actively recommending the creation and use of one. He's also encouraging the practice of annotation, though in commonplace form rather than within the book itself.

-

-

docdrop.org docdrop.org

-

Bent-note and Double-note Techniques

-

-

docdrop.org docdrop.orgUntitled1

-

MELODIC STRUCTURES»

https://docdrop.org/pdf/Bergonzi1992Melodic_Structures-4edv1_ocr.pdf/?src=ocr

Melodic Structures (Vol 1) Bergonzi, J 1994

-

-

forum.zettelkasten.de forum.zettelkasten.de

-

Todd Henry in his book The Accidental Creative: How to be Brilliant at a Moment's Notice (Portfolio/Penguin, 2011) uses the acronym FRESH for the elements of "creative rhythm": Focus, Relationships, Energy, Stimuli, Hours. His advice about note taking comes in a small section of the chapter on Stimuli. He recommends using notebooks with indexes, including a Stimuli index. He says, "Whenever you come across stimuli that you think would make good candidates for your Stimulus Queue, record them in the index in the front of your notebook." And "Without regular review, the practice of note taking is fairly useless." And "Over time you will begin to see patterns in your thoughts and preferences, and will likely gain at least a few ideas each week that otherwise would have been overlooked." Since Todd describes essentially the same effect as @Will but without mentioning a ZK, this "magic" or "power" seems to be a general feature of reviewing ideas or stimuli for creative ideation, not specific to a ZK. (@Will acknowledged this when he said, "Using the ZK method is one way of formalizing the continued review of ideas", not the only way.)

via Andy

Andy indicates that this review functionality isn't specific to zettelkasten, but it still sits in the framework of note taking. Given this, are there really "other" ways available?

-

- May 2023

-

www.nicksantalucia.com www.nicksantalucia.com

-

Santalucia, Nick. “The Zettelkasten in the Secondary Classroom.” Blog, July 6, 2021. https://www.nicksantalucia.com/blog/the-zettelkasten-in-the-secondary-classroom-k12.

-

-

getupnote.com getupnote.com

-

Suggested by Cato Minor<br /> Mac, Windows, Linux, iOS, Android

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

forum.zettelkasten.de forum.zettelkasten.de

-

@Will Thanks for always keeping up with your regular threads and considerations.

I've been keeping examples of people talking about the "magic of note taking" for a bit. I appreciate your perspectives on it. Personally I consider large portions of it to be bound up with the ideas of what Luhmann termed as "second memory", the use of ZK to supplement our memories, and the serendipity of combinatorial creativity. I've traced portions of it back to the practices of Raymond Llull in which he bound up old mnemonic techniques with combinatorial creativity which goes back to at least Seneca.

A web search for "combinatorial creativity" may be useful, but there's a good attempt at what it entails here: https://fs.blog/seneca-on-combinatorial-creativity/

-

The magic comes from the repetition of adding your thoughts to the notes you take and reviewing notes regularly.

Will Simpson feels that the magic of note taking stems from "the repetition of adding your thoughts to the notes you take and reviewing notes regularly".

I think it sems more from the serendipitous connections and resultant combinatorial creativity.

-

Links are where the magic happens.

cross reference: https://hypothes.is/a/QLyD4P6mEe2uC4O7z2QOOQ

-

-

forum.zettelkasten.de forum.zettelkasten.de

-

It is unfortunate that the German word for a box of notes is the same as the methodology surrounding Luhmann.

reply to dandennison84 at https://forum.zettelkasten.de/discussion/comment/17921/#Comment_17921

I've written a bit before on The Two Definitions of Zettelkasten, the latter of which has been emerging since roughly 2013 in English language contexts. Some of it is similar to or extends @dandennison84's framing along with some additional history.

Because of the richness of prior annotation and note taking traditions, for those who might mean what we're jokingly calling ZK®, I typically refer to that practice specifically as a "Luhmann-esque zettelkasten", though it might be far more appropriate to name them a (Melvil) "Dewey Zettelkasten" because the underlying idea which makes Luhmann's specific zettelkasten unique is that he was numbering his ideas and filing them next to similar ideas. Luhmann was treating ideas on cards the way Dewey had treated and classified books about 76 years earlier. Luhmann fortunately didn't need to have a standardized set of numbers the way the Mundaneum had with the Universal Decimal Classification system, because his was personal/private and not shared.

To be clear, I'm presently unaware that Dewey had or kept any specific sort of note taking system, card-based or otherwise. I would suspect, given his context, that if we were to dig into that history, we would find something closer to a Locke-inspired indexed commonplace book, though he may have switched later in life as his Library Bureau came to greater prominence and dominance.

Some of the value of the Dewey-Luhmann note taking system stems from the same sorts of serendipity one discovers while flipping through ideas that one finds in searching for books on library shelves. You may find the specific book you were looking for, but you're also liable to find some interesting things to read on the shelves around that book or even on a shelf you pass on the way to find your book.

Perhaps naming it and referring to it as the Dewey-Luhmann note taking system or the Dewey-Luhmann Zettelkasten may help to better ground and/or demystify the specific practices? Co-crediting them for the root idea and an early actual practice, respectively, provides a better framing and understanding, especially for native English speakers who don't have the linguistic context for understanding Zettelkästen on its own. Such a moniker would help to better delineate the expected practices and shape of a note taking practice which could be differentiated from other very similar ones which provide somewhat different affordances.

Of course, as the history of naming scientific principles and mathematical theorems after people shows us, as soon as such a surname label might catch on, we'll assuredly discover someone earlier in the timeline who had mastered these principles long before (eg: the "Gessner Zettelkasten" anyone?) Caveat emptor.

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

Edit: also, my antinet gaining some personality points by having parrot bite marks here and there. ‘:D

via u/nagytimi85 at https://www.reddit.com/r/antinet/comments/13s84q3/comment/jlof6b9/?utm_source=reddit&utm_medium=web2x&context=3

File this one under the most bizarre potential note collection damage vector: a parrot who bites index cards!

-

-

archive.org archive.org

-

https://archive.org/details/myapprenticeship0000beat/page/412/mode/2up

Appendix C: The Art of Note-Taking in My Apprenticeship (1926)

-

-

www.amazon.com www.amazon.com

-

I am wholly unsurprised that Harold Innis maintained a card index (zettelkasten) through his research life, but I am pleased to have found that his literary estate has done some work on it and published it. The introduction seems to have some fascinating material on the form and structure as well as decisions on how they decided to present and publish it.

https://www.amazon.com/Idea-Harold-Adams-Innis-Heritage/dp/0802063829/

-

-

-

I get by when I work by accumulating notes—a bit about everything, ideas cap-tured on the fly, summaries of what I have read, references, quotations . . . Andwhen I want to start a project, I pull a packet of notes out of their pigeonhole anddeal them out like a deck of cards. This kind of operation, where chance plays arole, helps me revive my failing memory.16

via: Didier Eribon, Conversations with Claude Lévi-Strauss (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991), vii–viii; Claude Lévi-Strauss, Structural Anthropology (New York: Basic Books, 1963), 129f.

-

system was described by Charles Darwin:I keep from thirty to forty large portfolios, in cabinets with labeled shelves, intowhich I can at once put a detached reference or memorandum. I have bought manybooks and at their ends I make an index of all the facts that concern my work.Before beginning on any subject I look to all the short indexes and make a generaland classified index, and by taking the one or more proper portfolios I have all theinformation collected during my life ready for use.13

via Nora Barlow ed., The Autobiography of Charles Darwin 1809–1882 vol. 1 (London: Collins, 1958), 137.

-

-

get.mem.ai get.mem.ai

-

I've had this on a list for ages, but never put into my digital notes...

-

-

jillianhess.substack.com jillianhess.substack.com

-

www.ploter.io www.ploter.ioPloter1

-

Modern all-in-one reader Read EPUBs, PDFs and audiobooks on all of your devices. Reading progress and highlights synced seamlessly.

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

Physical vs Digital Note Systems

There's a lot of useful detail hiding in this 15 minutes as an overview, but nothing new/interesting for me.

I will say that he completely misses a lot of the subtleties of indexing and multiple storage within the analog space, but it's likely because he's not done it personally or doesn't have enough experience there.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

notes.andymatuschak.org notes.andymatuschak.org

-

Evergreen notes should be atomicEvergreen notes should be concept-orientedEvergreen notes should be densely linkedPrefer associative ontologies to hierarchical taxonomiesWrite notes for yourself by default, disregarding audience

Deben ser de una forma en la que pueda tomar el concepto de lo que quería anotar solo con leer la nota, (como si fuera un guía definitiva en YT) tienen que estar enlazadas con otros conceptos (como el ejemplo de guía definitiva de YT) para tomar una idea más completa y amplia sobre la nota tienen que estar categorizadas por el concepto que estoy tratando, no sobre autor, libro, fecha. Tiene que sobre concepto general, evitamos tener millones de notas de diferentes categorías y las metemos todas en una categoría madre (sleep en vez de andrew huberman, o youtube) tengo que hacer notas para mi sin pensar que las voy a compartir, (que también puedo hacer) Y que puedan crecer, verlas como una red muy compleja como celulas o neuraonas en un cerebro que se concetan entre si hacer este tipo de notas con cada cosa interesante que encuentre y me gustaría guardar

-

-

patrickrhone.com patrickrhone.com

-

https://patrickrhone.com/dashplus/

referenced via Simon Woods at micro.camp https://hypothes.is/a/_GvLrPczEe2T-tfEqnLNhw

-

-

-

https://xtiles.app/en

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.marginnote.com www.marginnote.com

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

-

During his imprisonment, Gramsci wrote more than 30 notebooks and 3,000 pages of history and analysis. His Prison Notebooks are considered a highly original contribution to 20th-century political theory.

Antonio Gramsci, an Italian Marxist philosopher, journalist, writer, politician, and linguist, was imprisoned from 1926 until his death in 1937 as a vocal critic of Benito Mussolini. While in prison he wrote more than 3,000 pages in more than 30 notebooks. His Prison Notebooks comprise a fascinating contribution to political theory.

-

-

www.arno-schmidt-stiftung.de www.arno-schmidt-stiftung.de

-

https://www.arno-schmidt-stiftung.de/Archiv/Zettelarchiv.html

The »notes of the day« shown so far from Arno Schmidt's note box for »Zettel's Traum« can be downloaded here:

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

people are great at the collecting and categorizing pieces, but we're less good at going back in and connecting or expressing and this is where the value increases exponentially

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

More than just taking notes - Learning exhaust by Nicole van der Hoeven

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3L24rKggMX8

Nice framing to broadly define note taking as a form of learning exhaust, but broadly nothing new here for me.

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

An Inside Look into Obsidian Book Club

Several nice mentions of me throughout...

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

Requesting advice for where to put a related idea to a note I'm currently writing .t3_13gcbj1._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postBodyLink-VisitedLinkColor: #989898; } Hi! I am new to building a physical ZK. Would appreciate some help.Pictures here: https://imgur.com/a/WvyNVXfI have a section in my ZK about the concept of "knowledge transmission" (4170/7). The below notes are within that section.I am currently writing a note about how you have to earn your understanding... when receiving knowledge / learning from others. (Picture #1)Whilst writing this note, I had an idea that I'm not quite sure belongs on that note itself - and I'm not sure where it belongs. About how you also have to "earn" the sharing of knowledge. (Picture #2)Here are what I think my options are for writing about the idea "you have to earn your sharing of knowledge":Write this idea on my current card. 4170/7/1Write this idea on a new note - as a variant idea of my current note. 4170/7/1aWrite this idea on a new note - as a continuation of my current note. 4170/7/1/1Write this idea on a new note - as a new idea within my "knowledge transmission" branch. 4170/7/2What would you do here?

reply to u/throwthis_throwthat at https://www.reddit.com/r/antinet/comments/13gcbj1/requesting_advice_for_where_to_put_a_related_idea/

I don't accept the premise of your question. This doesn't get said often enough to people new to zettelkasten practice: Trust your gut! What does it say? You'll learn through practice that there are no "right" answers to these. Put a number on it, file it, and move on. Practice, practice, practice. You'll be doing this in your sleep soon enough. As long as it's close enough, you'll find it. Save your mental cycles for deeper thoughts than this.

Asking others for their advice is fine, but it's akin to asking a well-practiced mnemonist what visual image they would use to remember something. Everyone is different and has different experiences and different things that make their memories sticky for them. What works incredibly well for how someone else thinks and the level of importance they give an idea is never as useful or as "true" as how you think about it. Going with your gut is going to help you remember it better and is far likelier to make it easier to find in the future.

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

Jared Henderson writes excerpted ideas in block capital letters and his own observations and thoughts in small print as a means of distinguishing his own ideas from others.

Others might do this using other means: fonts, color, writing instrument, etc.

-

-

librarian.aedileworks.com librarian.aedileworks.com

-

The promise of using machine learning on your own notes to connect with external sources is not new. Andromeda Yelton’s HAMLET is six years old.

-

-

howaboutthis.substack.com howaboutthis.substack.com

-

Enter the venerable composition notebook. For $1.507, I get 180 pages at that composition book size (larger than A5) with a reasonably durable hard cover. The paper is quite acceptable for writing and I really don’t care if I make a huge mess within because it’s relatively inexpensive8.

At Mark Dykeman's rate, to convert to cheap composition books, he's looking at $26/year for the equivalent paper consumption. On a per day basis, it's $0.071 per day in paper.

This can be compared with my per day cost of $0.421 per day for index cards, which is more expensive, though not $1-2 per day for more expensive notebooks.

-

I take a lot of notes during my day job. More like a huge amount of notes. On paper. As an experiment I started using several Dingbats* notebooks during the day job to see how they would work4 for me. After about 9 weeks of trials, I learned that I could fill up a 180 page notebook in about 3 weeks, plus or minus a few days. Unfortunately, when you factor in the cost of these notebooks, that’s like spending $1 - $2 per day on notebooks. Dingbats* are lovely, durable notebooks. But my work notes are not going to be enshrined in a museum for the ages5 and until I finally get that sponsorship from Dingbats* or Leuchtuurm19176, I probably need a different solution.

Mark Dykeman indicates that at regular work, he fills up a 180 page notebook and at the relatively steep cost of notebooks, he's paying $1-2 a day for paper.

This naturally brings up the idea of what it might cost per day in index cards for some zettlers' practices. I've already got some notes on price of storage...

As a rough calculation, despite most of my note taking being done digitally, I'm going through a pack of 500 Oxford cards at $12.87 every 5 months at my current pace. This is $0.02574 per card and 5 months is roughly 150 days. My current card cost per day is: $0.02574/card * 500 cards / (150 days) = $12.78/150 days = $0.0858 per day which is far better than $2/day.

Though if I had an all-physical card habit, I would be using quite a bit more.

On July 3, 2022 I was at 10,099 annotations and today May 11, 2023 I'm at 15,259 annotations. At one annotation per card that's 5,160 cards in the span of 312 days giving me a cost of $0.02574/card * 5,160 cards / 312 days = $0.421 per day or an average of $153.75 per year averaging 6,036 cards per year.

(Note that this doesn't also include the average of three physical cards a day I'm using in addition, so the total would be slightly higher.)

Index cards are thus, quite a bit cheaper a habit than fine stationery notebooks.

-

-

jillianhess.substack.com jillianhess.substack.com

-

’ve been studying notebooks for over a decade and I still haven’t landed on a perfect organization method. I have, however, found the perfect pen: uni-ball signo, .38mm. I discovered them while teaching in Korea in 2008 and haven’t looked back.

It can't be a good sign that an academic who has spent over a decade studying notebooks and note taking still hasn't found the "perfect" organization method.

-

-

jillianhess.substack.com jillianhess.substack.com

-

4/20/52[Keime.] Murder by mental nagging. Woman nags her husband to suicide, which he does so it looks like he has been murdered. Poison, which he puts in her desk drawer, her fingerprints on it.

Jillian Hess noted that Patricia Highsmith uses the German word Keime, meaning "germ of an idea" in her cahiers to indicate ideas which might be used in her novels or short stories.

-

I highly recommend notebooks for writers, a small one if one has to be out on a job all day, a larger one if one has the luxury of staying at home.

from Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction

-

-

jillianhess.substack.com jillianhess.substack.com

-

Write down all these slender ideas. It is surprising how often one sentence, jotted in a notebook, leads immediately to a second sentence. A plot can develop as you write notes. Close the notebook and think about it for a few days — and then presto! you’re ready to write a short story. — Patricia Highsmith: Her Diaries and Notebooks

quote is from Highsmith's Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction

I love the concept of "slender ideas" as small, fleeting notes which might accumulate into something if written down. In saying "Close the notebook and think about it for a few days" Patricia Highsmith seems to be suggesting that one engage in diffuse thinking, passive digesting, or mulling rather than active or proactive thinking.

She also invokes the magic word "presto!" (which she exclaims) as if to indicate that magically the difficult work of writing is somehow no longer difficult. Many writers seem to indicate that this is a phenomenon, but never seem to put their finger on the mechanism of why it happens. Some seems to stem from the passive digestion over days with diffuse thinking, with portions may also stem from not starting from a blank page and having some material to work against instead of a vacuum.

From Patricia Highsmith: Her Diaries and Notebooks: 1941-1995 (Swiss Literary Archives)

-

-

jillianhess.substack.com jillianhess.substack.com

-

What's with the bees? by [[Jillian Hess]]

A tipping out of Hess' zettelkasten on the theme of bees (apes) in note taking.

-

As they flit like so many little bees between Greek and Latin authors of every species, here noting down something to imitate, here culling some notable saying to put into practice in their behavior, there getting by heart some witty anecdote to relate among their friends, you would swear you were watching the Muses at graceful play in the lovely pastures of Mount Helicon, gathering flowers and marjoram to make well-woven garlands. —The Adages of Erasmus

-

The bee plunders the flowers here and there, but afterwards they make of them honey, which is all theirs; it is no longer thyme or marjoram. Even so with the pieces borrowed from others; he will transform and blend them to make a work that is all his own, to wit, his judgment — The Complete Essays of Michel de Montaigne

Cross reference with Seneca's note taking metaphors with apes.

-

Besides the metaphor of the honeybee, Seneca also compares this method to a stomach digesting food as well as a choir that produces one sound from many harmonized voices.

In addition to the honeybee metaphor, Seneca compared note taking and collecting sententiae to a stomach digesting food and a choir producing a harmonized sound out of many voices.

(Sources from these last two? Potentially Epistle LXXXIV?)

-

-

jillianhess.substack.com jillianhess.substack.com

-

Looking forward to being notespired!

notespired

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

It’s great that there’s interest in this stuff. Your articles are inspiring, as is Jillian Hess’s NotesSubstack, team Greene/Holiday/Oppenheimer, and the German scholars who focus on the technology of writing, such as Hektor Haarkötter. But I don’t see this as nostalgia. For me it’s history in service of the present and the future.

reply to u/atomicnotes at https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/13cqnsk/comment/jjkwc05/?utm_source=reddit&utm_medium=web2x&context=3

Definitely history in service of the present and the future. Too many people are doing some terribly hard work attempting to reinvent wheels which have been around for centuries.

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

Note taking should serve a specific purpose; it should be a means to some end.

-

Note taking can also be done to create a database (a la Beatrice Webb's scientific note taking).

-

Writing permanent notes was time consuming as f***.

The framing of "permanent notes" or "evergreen notes" has probably hurt a large portion of the personal knowledge management space. Too many people are approaching these as some sort of gold standard without understanding their goal or purpose. Why are you writing such permanent/evergreen notes? Unless you have an active goal to reuse a particular note for a specific purpose, you're probably wasting your time. The work you put into the permanent note is to solidify an idea which you firmly intend to reuse again in one or more contexts. The whole point of "evergreen" as an idea is that it can actively be reused multiple times in multiple places. If you've spent time refining it to the nth degree and writing it well, then you had better be doing so to reuse it.

Of course many writers will end up (or should end up) properly contextualizing individual ideas and example directly into their finished writing. As a result, one's notes can certainly be rough and ready and don't need to be highly polished because the raw idea will be encapsulated somewhere else and then refined and rewritten directly into that context.

Certainly there's some benefit for refining and shaping ideas down to individual atomic cores so that they might be used and reused in combination with other ideas, but I get the impression that some think that their notes need to be highly polished gems. Even worse, they feel that every note should be this way. This is a dreadful perspective.

For context I may make 40 - 60 highlights and annotations on an average day of reading. Of these, I'll review most and refine or combine a few into better rougher shape. Of this group maybe 3 - 6 will be interesting enough to turn into permanent/evergreen notes of some sort that might be reused. And even at this probably only one is interesting enough to be placed permanently into my zettelkasten. This one will likely be an aggregation of many smaller ideas combined with other pre-existing ideas in my collection; my goal is to have the most interesting and unique of my own ideas in my permanent collection. The other 2 or 3 may still be useful later when I get to the creation/writing stage when I'll primarily focus on my own ideas, but I'll use those other rougher notes and the writing in them to help frame and recontextualize the bigger ideas so that the reader will be in a better place to understand my idea, where it comes from, and why it might be something they should find interesting.

Thus some of my notes made while learning can be reused in my own ultimate work to help others learn and understand my more permanent/evergreen notes.

If you think that every note you're making should be highly polished, refined, and heavily linked, then you're definitely doing this wrong. Hopefully a few days of attempting this will disabuse you of the notion and you'll slow down to figure out what's really worth keeping and maintaining. You can always refer back to rough notes if you need to later, but polishing turds is often thankless work. Sadly too many misread or misunderstand articles and books on the general theory of note taking and overshoot the mark thinking that the theory needs to be applied to every note. It does not.

If you find that you're tiring of making notes and not getting anything out of the process, it's almost an assured sign that you're doing something wrong. Are you collecting thousands of ideas (bookmarking behavior) and not doing anything with them? Are you refining and linking low level ideas of easy understanding and little value? Take a step back and focus on the important and the new. What are you trying to do? What are you trying to create?

-

The few notes I did refer back to frequently where checklists, self-written instructions to complete regular tasks, lists (reading lists, watchlists, etc.) or recipes. Funnily enough the ROI on these notes was a lot higher than all the permanent/evergreen/zettel notes I had written.

Notes can be used for different purposes.

- productivity

- Knowledge

- basic sense-making

- knowledge construction and dispersion

The broad distinction is between productivity goals and knowledge. (Is there a broad range I'm missing here within the traditions?) You can take notes about projects that need to be taken care of, lists of things to do, reminders of what needs to be done. These all fall within productivity and doing and checking them off a list will help one get to a different place or location and this can be an excellent thing, particularly when the project was consciously decided upon and is a worthy goal.

Notes for knowledge sake can be far more elusive for people. The value here generally comes with far more planning and foresight towards a particular goal. Are you writing a newsletter, article, book, or making a video or performance of some sort (play, movie, music, etc.)? Collecting small pieces of these things on a pathway is then important as you build your ideas and a structure toward some finished product.

Often times, before getting to this construction phase, one needs to take notes to be able to scaffold their understanding of a particular topic. Once basically understood some of these notes may be useless and not need to be reviewed, or if they are reviewed, it is for the purpose of ensconcing ideas into long term memory. Once this is finished, then the notes may be broadly useless. (This is why it's simple to "hide them with one's references/literature notes.) Other notes are more seminal towards scaffolding ideas towards larger projects for summarization and dissemination to other audiences. If you're researching a topic, a fair number of your notes will be used to help you understand the basics while others will help you to compare/contrast and analyze. Notes you make built on these will help you shape new structures and new, original thoughts. (note taking for paradigm shifts). These then can be used (re-used) when you write your article, book, or other creative project.

-

I used Apple Notes, Evernote, Roam, Obsidian, Bear, Notion, Anki, RemNote, the Archive and a few others. I was pondering about different note types, fleeting, permanent, different organisational systems, hierarchical, non-hierarchical, you know the deal. I often felt lost about what to takes notes on and what not to take notes on.

Example of someone falling prey to shiny object syndrome, switching tools incessantly, then focusing on too many of the wrong things/minutiae and getting lost in the shuffle.

Don't get caught up into this. Understand the basics of types of notes, but don't focus on them. Let them just be. Does what you've written remind you of the end goal?

Tags

- personal knowledge management

- note taking advice

- types of notes

- note taking as aide-mémoire

- examples

- note taking why

- note taking for paradigm shifts

- card index as database

- shiny object syndrome

- note taking is learning

- evergreen notes

- note taking affordances

- note taking process

- permanent notes

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

I'm not actually setting a productivity goal, I'm just tracking metadata because it's related to my research. Of which the ZettelKasten is one subject.That being said, in your other post you point to "Quality over Quantity" what, in your opinion, is a quality note?Size? Number of Links? Subjective "goodness"?

reply to u/jordynfly at https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/13b0b5c/comment/jjcu3cn/?utm_source=reddit&utm_medium=web2x&context=3

I'm curious what your area of research is? What are you studying with respect to Zettelkasten?

Caveat notetarius. Note collections are highly idiosyncratic to the user or intended audience, thus quality will vary dramatically on the creator's needs and future desires and potential uses. Contemporaneous, very simple notes can be valuable for their initial sensemaking and quite often in actual practice stop there.

Ultimately, only the user can determine perceived quality and long term value for themselves. Future generations of historians, anthropologists, scholars, and readers, might also find value in notes and note collections, but it seems rare that the initial creators have written them with future readers and audiences in mind. Often they're less useful as the external reader is missing large swaths of context.

For my own personal notes, I consider high quality notes to be well-sourced, highly reusable, easily findable, and reasonably tagged/linked. My favorite, highest quality notes are those that are new ideas which stem from the combination of two high quality notes. With respect to subjectivity, some of my philosophy is summarized by one of my favorite meta-zettels (alt text also available) from zettelmeister Umberto Eco.

Anecdotally, 95% of my notes are done digitally and in public, but I've only got scant personal evidence that anyone is reading or interacting with them. I never write them with any perceived public consumption in mind (beyond the readers of the finished pieces that ultimately make use of them), but it is often very useful to get comments and reactions to them. I'm only aware of a small handful of people publishing their otherwise personal note collections (usually subsets) to the web (outside of social media presences which generally have a different function and intent).

Intellectual historians have looked at and documented external use cases of shared note collections, commonplace books, annotated volumes, and even diaries. There are even examples of published (usually posthumously) commonplace books, waste books, etc., but these are often for influential public and intellectual figures. Here Ludwig Wittgenstein's Zettel, Walter Benjamin's Arcades Project, Vladimir Nabokov's The Original of Laura, Roland Barthes' Mourning Diary, Georg Christoph Lichtenberg's Waste Books, Ralph Waldo Emmerson, Ronald Reagan's card index commonplace, Stobaeus' Anthology, W. H. Auden's A Certain World, and Robert Southey’s Common-Place Book come quickly to mind not to mention digitized scholarly collections of Niklas Luhmann, W. Ross Ashby, S.D. Goitein, Jonathan Edwards' Miscellanies, and Aby Warburg's notes. Some of these latter will give you an idea of what they may have thought quality notes to have been for them, but often they mean little if nothing to the unstudied reader because they lack broader context or indication of linkages.

-

Why are folks so obsessed with notes per day? Perhaps a proxy for toxic capitalism and productivity issues? Is the number of notes the best measure or the things they allow one to do after having made them? What is the best measure? Especially when there are those who use them for other purposes like lecturing, general growth, knowledge acquisition, or even happiness?

-

-

www.napkin.one www.napkin.one

-

https://www.napkin.one/

Yet another collection app that belies the work of taking, making, and connecting notes.

Looks pretty and makes a promise, but how does it actually deliver? How much work and curation is involved? What are the outputs at the other end?

-

- Apr 2023

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

-

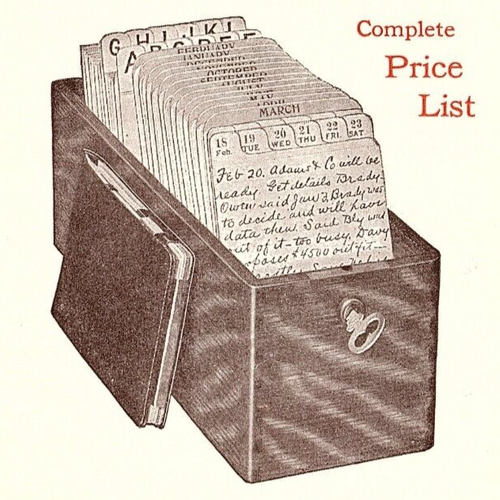

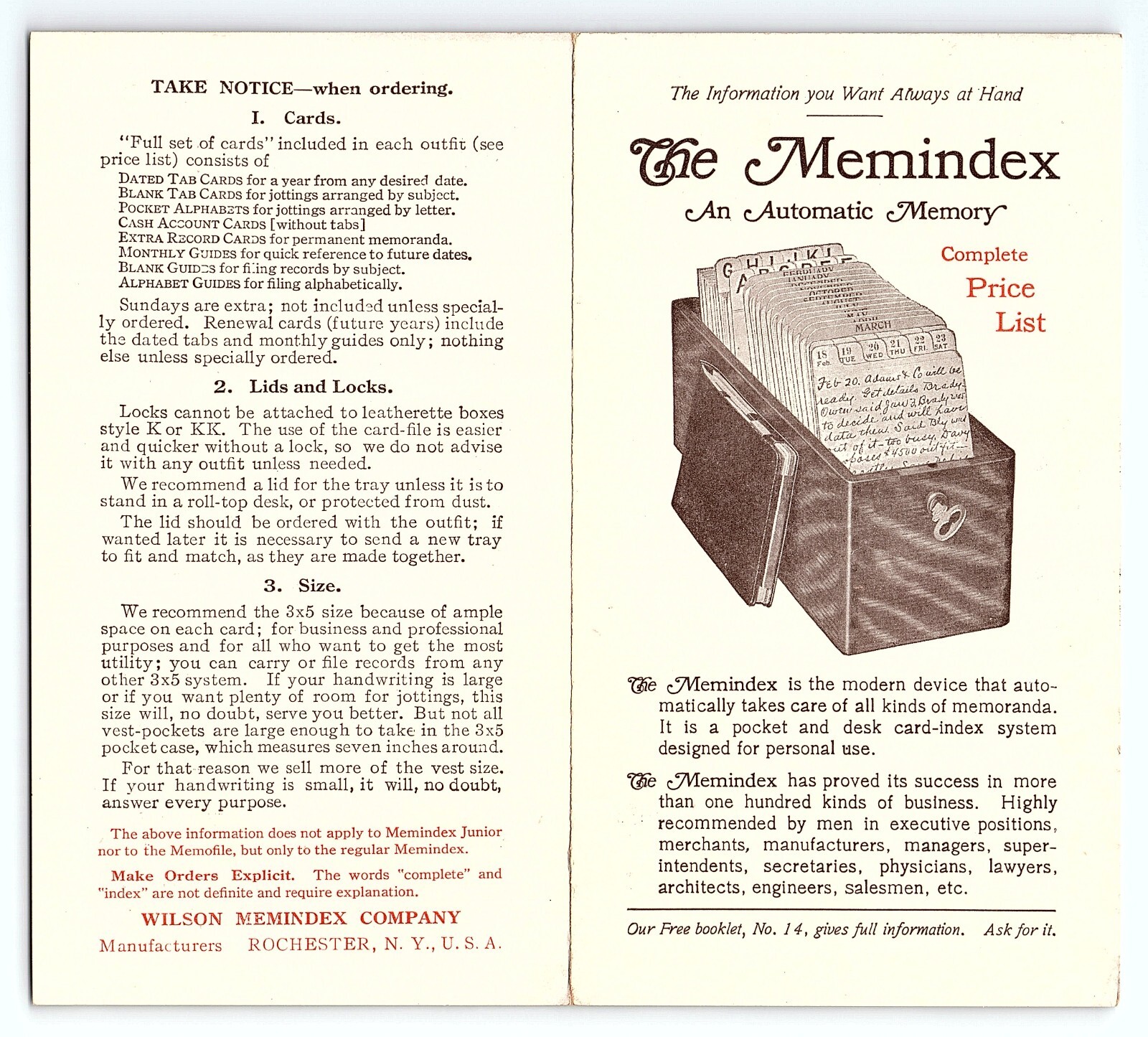

Catalog cards were 2 by 5 inches (5 cm × 13 cm); the Harvard College size.

Early library card catalogs used cards that were 2 x 5" cards, the Harvard College size, before the standardization of 3 x 5" index cards.

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

Emergent note taking: what ants can teach us about notes

Nothing new to me, but interesting to see part of Nicole van der Hoeven's process.

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

Zhao briefly describes Cal Newport's Questions, Evidence, Conclusions (QEC) framework which she uses as a framework for quickly annotating books and then making notes from those annotations later.

How does QEC differ from strategies in Adler/Van Doren?

-

-

www.dalekeiger.net www.dalekeiger.net

-

Roy Peter Clark, writing scholar and coach at The Poynter Institute, says, “Reports give readers information. Stories give readers experience.” I would add: An article is generic; a story is unique.

There's something interesting lurking here on note taking practice as well.

Generic notes for learning may rephrase or summarize an idea int one's own words and are equivalent to basic information or articles as framed by Clark/Keiger. But in building towards something, that goes beyond the basic, one should strive in their notes to elicit experience and generate insight; take the facts and analyze them, create something new, interesting, and unique.

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

Mobility of the Antinet

reply to u/523tailor at https://www.reddit.com/r/antinet/comments/12xpq6s/mobility_of_the_antinet/

Many parts of the process are small bits that loan themselves to filling 5 minutes here or 10 minutes there, so mobility is a good thing, especially if you have a schedule that moves you around. I use a few of the following to help on the mobility front:

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

How I annotate books as a PhD student (simple and efficient)

She's definitely not morally against writing in her books, but there are so many highlights and underlining that it's almost useless.

She read the book four times because she didn't take good enough notes on it the first three times.

Bruno Latour's Down to Earth

Tools: - sticky tags (reusable) - purple for things that draw attention - yellow/green referencing sources, often in bibliography - pink/orange - extremely important - highlighter - Post It notes with longer thoughts she's likely to forget, but also for writing summaries in her own words

Interesting to see another Bruno Latour reference hiding in a note taking context. See https://hypothes.is/a/EbNKbLIaEe27q0dhRVXUGQ

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

thanks for the comprehensive overview; i'm going back to grad school after working for a couple years, any guides in particular you would recommend for getting up to speed and setting up a good workflow to keep track of articles and other references + store files and notes?

reply to u/whysofancy at https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/12u8gbv/comment/jh61vqw/?utm_source=reddit&utm_medium=web2x&context=3

My general advice is to keep things as stupidly simple as possible and use as few tools/platforms as you can get away with.

If you haven't come across them, I highly recommend these two books:

- Eco, Umberto. How to Write a Thesis. Translated by Caterina Mongiat Farina and Geoff Farina. 1977. Reprint, Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press, 2015. https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/how-write-thesis.

- Adler, Mortimer J., and Charles Van Doren. How to Read a Book: The Classical Guide to Intelligent Reading. Revised and Updated ed. edition. 1940. Reprint, Touchstone, 2011.

You might also appreciate the short article by Mills:

Mills, C. Wright. “On Intellectual Craftsmanship (1952).” Society 17, no. 2 (January 1, 1980): 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02700062.

Chances are pretty good your college/university's library does regular tutorials for tools like Zotero, particularly at the beginning of the term. Raul Pacheco has some good notes/ideas which may be helpful for things like literature reviews: http://www.raulpacheco.org/resources/. For Hypothes.is, try starting with this tutorial by their head of education: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=09z5hyBMs8s. If you're using Obsidian with Zotero, I'd recommend this walk through https://forum.obsidian.md/t/zotero-zotfile-mdnotes-obsidian-dataview-workflow/15536 and this video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XbGJH08ZfCs. If you have other tools in mind that you'd like to use, let the community know and perhaps we can make some suggestions about tutorials, but really, just jump in and try something out. Search YouTube and see what you find.

At the end of the day, start using a tool or two and simply practice with them. Practice, practice, and practice some more as that's what you'll be doing regularly in grad school. Read, write notes, organize them, write short articles or papers as practice. You'll eventually build up enough for a much longer thesis.

-

-

zettelkasten.de zettelkasten.de

-

Why the Single Note Matters by Sascha Fast

Diligence is required.

-

-

wi-calm.sas.ac.uk wi-calm.sas.ac.uk

-

The searchable digital archive for Aby Warburg's zettelkasten at The Warburg Institute: https://wi-calm.sas.ac.uk/CalmView/Default.aspx

-

-

wi-calm.sas.ac.uk wi-calm.sas.ac.uk

-

An example of a digital record of a physical divider in Aby Warburg's zettelkasten for Jakob Burkhardt with subsections listed.

Ref No: WIA III.2.1. ZK/4a/2<br /> Title: Jakob Burkhardt Briefe<br /> Physical Description: Divider<br /> Contents: Subsections: 1rst level: Vorträg Burckhardt 1927 Sommersemester [appr. 56 items, numbered and unnumbered]; 2nd level: Burckhardt an Nietzsche; 3rd level: Brief Nietzsches an Burckhardt 6 Januar 1889. 2nd level: Jakob Burckhardt und die nordische Kunst Conversations Lexikon, Burckhardt Festwesen, zu Rougemont Cicerone, Wanderer in der Schweiz, Hedlinger, Hedlinger.

-

-

wi-calm.sas.ac.uk wi-calm.sas.ac.uk

-

Collection of Index Card Boxes (Zettelkästen) Aby Warburg’s collection of index cards (III.2.1.ZK), containing notes, bibliographical references, printed material and letters, was compiled throughout the scholar’s life. Ninety-six boxes survive, each containing between 200 and 800 individually numbered index cards. Cardboard dividers and envelopes group these index cards into thematic sections. The online catalogue reproduces the structure of the dividers and sub-dividers with their original titles in German and consists of about 3,200 items. Since the titles are transcribed (and not translated into English) you can only search for words in the original German.

Aby Warburg's extant zettelkasten at the Warburg Institute's Archive consists of ninety-six surviving boxes which contain between 200-800 individually numbered index cards. Dividers and envelopes are used within the boxes to separate the cards into thematic sections.

The digitized version is transcribed in the original German and is not available translated into English (at least as of 2023). The digitized version maintains the structure of the dividers and consists of only about 3,200 items.

-

-

warburg.sas.ac.uk warburg.sas.ac.uk

-

A full catalogue of Aby Warburg's correspondence, the Institute's correspondence up to 1933 and Warburg's index card boxes is available online through the Warburg Institute Archive online database.

A full catalog of Aby Warburg's 104 index card boxes (reference: WIA III.2.1.ZK) are available online by way of The Warburg Institute's online database at http://wi-calm.sas.ac.uk/calmview/. They are catalogued at the file level.

via https://warburg.sas.ac.uk/archive/archive-online-catalogues

-

-

themindfulteacher.medium.com themindfulteacher.medium.com

-

Stream of Consciousness to Atomic Notes: A Powerful Note-Taking Workflow

Broadly a workflow that takes journaling/morning pages and then progressively refines them into atomic-like notes.

Uses the idea of open loops from the GTD-space.

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

does my zettelkasten make writing... harder?

Worried about self-plagiarizing in the future? Others like Hans Blumenberg have struck through used cards with red pencil. This could also be done with metadata or other searchable means in the digital realm as well. (See: https://hypothes.is/a/mT8Twk2cEe2bvj8lq2Lgpw)

General problems she faces: 1. Notetaking vs. writing voice (shifting between one and another and not just copy/pasting) 2. discovery during writing (put new ideas into ZK as you go or just keep writing on the page when the muse strikes) 3. Linearity of output: books are linear and ZK is not

Using transclusion may help in the initial draft/zero draft?<br /> ie: ![[example]] (This was mentioned in the comments as well.)

directional vs. indirectional notes - see Sascha Fast's article

Borrowing from the telecom/cable industry, one might call this the zettelkasten "last mile problem". I've also referred to it in the past as the zettelkasten output problem. (See also the description and comments at https://boffosocko.com/2022/07/12/call-for-model-examples-of-zettelkasten-output-processes/ as well as some of the examples linked at https://boffosocko.com/research/zettelkasten-commonplace-books-and-note-taking-collection/)

Many journal articles that review books (written in English) in the last half of the 20th century which include the word zettelkasten have a negative connotation with respect to ZK and frequently mention the problem that researchers/book writers have of "tipping out their ZKs" without the outlining and argument building/editing work to make their texts more comprehensible or understandable.

Ward Cunningham has spoken in the past about the idea of a Markov Monkey who can traverse one's atomic notes in a variety of paths (like a Choose Your Own Adventure, but the monkey knows all the potential paths). The thesis in some sense is the author choosing a potential "best" path (a form of "travelling salesperson problem), for a specific audience, who presumably may have some context of the general area.

Many mention Sonke Ahrens' book, but fail to notice Umberto Eco's How to Write a Thesis (MIT, 2015) and Gerald Weinberg's "The Fieldstone Method (Dorset House, 2005) which touch a bit on these composition problems.

I'm not exactly sure of the particulars and perhaps there isn't enough historical data to prove one direction or another, but Wittgenstein left behind a zettelkasten which his intellectual heirs published as a book. In it they posit (in the introduction) that rather than it being a notetaking store which he used to compose longer works, that the seeming similarities between the ideas in his zettelkasten and some of his typescripts were the result of him taking his typescripts and cutting them up to put into his zettelkasten. It may be difficult to know which direction was which, but my working hypothesis is that the only way it could have been ideas from typescripts into his zettelkasten would have been if he was a "pantser", to use your terminology, and he was chopping up ideas from his discovery writing to place into contexts within his zettelkasten for later use. Perhaps access to the original physical materials may be helpful in determining which way he was moving. Cross reference: https://hypothes.is/a/BptoKsRPEe2zuW8MRUY1hw

Some helpful examples: - academia : Victor Margolin - fiction/screenwriting: - Dustin Lance Black - Vladimir Nabokov - others...

-

-

notes.andymatuschak.org notes.andymatuschak.org

-

Write notes for yourself by default, disregarding audience<br /> by Andy Matuschak

-

-

Local file Local file

-

Of all skill, part is infused by precept, and part is obtained by habit.SAMUEL JOHNSON

link to: - https://hypothes.is/a/hkyPEtm9Ee21MFP9ynnj0g

-

one must also submit to the discipline provided by imitationand practice.

Too many zettelkasten aspirants only want the presupposed "rules" for keeping one or are interested in imitating one or another examples. Few have interest in the actual day to day practice and these are often the most adept. Of course the downside of learning some of the pieces online leaves the learner with some (often broken) subset of rules and one or two examples (often only theoretical) and then wonder why their actual practice is left so wanting.

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

One idea to store pictures of an analog Zettelkasten: Tropy - it's a side project to Zotero. https://tropy.org/

-

-

-

any easy strategies to improve my notetaking?

reply to u/all_flowers_in_time_ at https://www.reddit.com/r/NoteTaking/comments/12g3idj/any_easy_strategies_to_improve_my_notetaking/

In many ways I was just like you in school...

Some of it depends on what your notes are for. Are you using them to write things in your own words to increase understanding and tie them into other ideas? Are you using them as reminders? Are you using them to build material for later (papers, articles, write a book, other?) For memorization?

Your notes look like they've got a Cornell Notes appearance, so perhaps more formally structuring your pages that way will help? Creating sample test questions afterward for practice and recall can be highly useful and force you to create answers which is dramatically more productive than simply reviewing over notes which usually creates a false sense of familiarity.

If you're using them for memorization, then perhaps convert the notes after lecture into flash cards (physical cards, Anki, Mnemosyne, etc.) that you can use for spaced repetition.

If you're using them to later create other content, then perhaps a commonplace book or zettelkasten structure may be helpful for cross indexing ideas. If you're not familiar with these, try out the following book which covers all of these use cases and mores:

Ahrens, Sönke. How to Take Smart Notes: One Simple Technique to Boost Writing, Learning and Thinking – for Students, Academics and Nonfiction Book Writers. Create Space, 2017.

I wish I had been able to do so when I was a student.

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

Benefits of sharing permanent notes .t3_12gadut._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postBodyLink-VisitedLinkColor: #989898; }

reply to u/bestlunchtoday at https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/12gadut/benefits_of_sharing_permanent_notes/

I love the diversity of ideas here! So many different ways to do it all and perspectives on the pros/cons. It's all incredibly idiosyncratic, just like our notes.

I probably default to a far extreme of sharing the vast majority of my notes openly to the public (at least the ones taken digitally which account for probably 95%). You can find them here: https://hypothes.is/users/chrisaldrich.

Not many people notice or care, but I do know that a small handful follow and occasionally reply to them or email me questions. One or two people actually subscribe to them via RSS, and at least one has said that they know more about me, what I'm reading, what I'm interested in, and who I am by reading these over time. (I also personally follow a handful of people and tags there myself.) Some have remarked at how they appreciate watching my notes over time and then seeing the longer writing pieces they were integrated into. Some novice note takers have mentioned how much they appreciate being able to watch such a process of note taking turned into composition as examples which they might follow. Some just like a particular niche topic and follow it as a tag (so if you were interested in zettelkasten perhaps?) Why should I hide my conversation with the authors I read, or with my own zettelkasten unless it really needed to be private? Couldn't/shouldn't it all be part of "The Great Conversation"? The tougher part may be having means of appropriately focusing on and sharing this conversation without some of the ills and attention economy practices which plague the social space presently.

There are a few notes here on this post that talk about social media and how this plays a role in making them public or not. I suppose that if I were putting it all on a popular platform like Twitter or Instagram then the use of the notes would be or could be considered more performative. Since mine are on what I would call a very quiet pseudo-social network, but one specifically intended for note taking, they tend to be far less performative in nature and the majority of the focus is solely on what I want to make and use them for. I have the opportunity and ability to make some private and occasionally do so. Perhaps if the traffic and notice of them became more prominent I would change my habits, but generally it has been a net positive to have put my sensemaking out into the public, though I will admit that I have a lot of privilege to be able to do so.

Of course for those who just want my longer form stuff, there's a website/blog for that, though personally I think all the fun ideas at the bleeding edge are in my notes.

Since some (u/deafpolygon, u/Magnifico99, and u/thiefspy; cc: u/FastSascha, u/A_Dull_Significance) have mentioned social media, Instagram, and journalists, I'll share a relevant old note with an example, which is also simultaneously an example of the benefit of having public notes to be able to point at, which u/PantsMcFail2 also does here with one of Andy Matuschak's public notes:

[Prominent] Journalist John Dickerson indicates that he uses Instagram as a commonplace: https://www.instagram.com/jfdlibrary/ here he keeps a collection of photo "cards" with quotes from famous people rather than photos. He also keeps collections there of photos of notes from scraps of paper as well as photos of annotations he makes in books.

It's reasonably well known that Ronald Reagan shared some of his personal notes and collected quotations with his speechwriting staff while he was President. I would say that this and other similar examples of collaborative zettelkasten or collaborative note taking and their uses would blunt u/deafpolygon's argument that shared notes (online or otherwise) are either just (or only) a wiki. The forms are somewhat similar, but not all exactly the same. I suspect others could add to these examples.

And of course if you've been following along with all of my links, you'll have found yourself reading not only these words here, but also reading some of a directed conversation with entry points into my own personal zettelkasten, which you can also query as you like. I hope it has helped to increase the depth and level of the conversation, should you choose to enter into it. It's an open enough one that folks can pick and choose their own path through it as their interests dictate.

-

-

www.reddit.com www.reddit.com

-

To buy or not to buy a course? And, if the latter, which one? .t3_12fowjy._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postBodyLink-VisitedLinkColor: #989898; } questionSo, I've been considering buying an online course for Zettelkasten (in Obsidian). Thing is... There are a bunch of them. Two (maybe three) questions:Is it worth it? Has anyone gone down that path and care to share their experience?Any recommendations? I've seen a bunch of options and really don't have any hints on how to evaluate them.

reply to u/Accomplished-Tip-597 at https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/12fowjy/to_buy_or_not_to_buy_a_course_and_if_the_latter/

Which "industry", though? Productivity? Personal Knowledge Management? Neither of these are focused on the idea of a Luhmann-esque specific zettelkastenare they?

For the original poster, what is your goal in taking a course? What do you want to get out of it? What are you going to use such a system for? The advice you're looking for will hinge on these.

Everyone's use is going to be reasonably idiosyncratic, so not knowing anything else, my general recommendation (to minimize time, effort, and expense) would be to read one of the following (for free), practice at some of it for a few weeks before you do anything else. Then if you need it, talk u/taurusnoises into a few consultations based on what you'd like to accomplish. He's one of the few who does this who's got experience in the widest variety of traditions in addition to expertise in the platform you want (though I'd still recommend him if you were using something else.)

- https://zettelkasten.de/posts/overview/

- https://minnstate.pressbooks.pub/write/ (just 1-7, though the rest is profitable)

- https://www.academia.edu/35101285/Creating_a_Commonplace_Book_CPB_

-

-

www.vousnousils.fr www.vousnousils.fr

-

L’évaluation du travail doit découler de l’appréciation du travail uniquement : si la copie d’un élève mérite 19, il doit obtenir 19, même si c’est un perturbateur. Par contre, cela n’empêche pas l’enseignant de lui mettre une heure de colle pour son comportement !

-

-

zettelkasten.de zettelkasten.de

-

after decades of using the Zettelkasten it might become impossible to access it from your place at the desk. To mitigate this issue, it is recommended to use normal (thin) paper instead of (thick) index cards.

After having used his zettelkasten for 26 years, Luhmann mentions that he chose normal paper as his substrate for note taking over thicker index cards to save on storage space and particularly to make it possible to keep more material closer to his desk rather than need to store it at larger distances within his office. This allows more slips per drawer and also tends to have an effect on productivity with respect to daily use and searching.

One might need to balance this out with frequency of use and slip wear, as some slips in his box show heavy use and wear, especially at the top.

-

If you have to write anyway, it is pragmatic to exploit this activity by creating a system of notes that can act as a competent communication partner.

-

-

zettelkasten.de zettelkasten.de

-

Fast, Sascha. “Field Report #5: How I Prepare Reading and Processing Effective Notetaking by Fiona McPherson.” Zettelkasten Method (blog), March 29, 2022. https://zettelkasten.de/posts/field-report-5-reading-processing-effective-notetaking-mcpherson/.

-

-

forum.zettelkasten.de forum.zettelkasten.de

-

There is no real difference if you think about the boundaries between reading and notetaking. Moving the eyes over text: Sounds like reading. Highlighting key words while reading: Still sounds like reading. Jotting down keywords in the margins: Some writing, but still could count as reading. Writing tasks in the marings (e.g. "Should compare that to Buddhism"): Don't know. Reformulating key sections in your own words: Sounds like writing. But could be just the externalisation of what could be internal. Does make a difference if you stop and think about what you read or do it in written form?

Perhaps there is a model for reading and note taking/writing with respect to both learning and creating new knowledge that follows an inverse mapping in a way similar to that seen in Galois theory?

Explore this a bit to see what falls out.

-

-

-

How do I store when coming across an actual FACT? .t3_12bvcmn._2FCtq-QzlfuN-SwVMUZMM3 { --postTitle-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postTitleLink-VisitedLinkColor: #9b9b9b; --postBodyLink-VisitedLinkColor: #989898; } questionLet's say I am trying to absorb a 30min documentary about the importance of sleep and the term human body cells is being mentioned, I want to remember what a "Cell" is so I make a note "What is a Cell in a Human Body?", search the google, find the definition and paste it into this note, my concern is, what is this note considered, a fleeting, literature, or permanent? how do I tag it...

reply to u/iamharunjonuzi at https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/12bvcmn/how_do_i_store_when_coming_across_an_actual_fact/

How central is the fact to what you're working at potentially developing? Often for what may seem like basic facts that are broadly useful, but not specific to things I'm actively developing, I'll leave basic facts like that as short notes on the source/reference cards (some may say literature notes) where I found them rather than writing them out in full as their own cards.

If I were a future biologist, as a student I might consider that I would soon know really well what a cell was and not bother to have a primary zettel on something so commonplace unless I was collecting various definitions to compare and contrast for something specific. Alternately as a non-biologist or someone that doesn't use the idea frequently, then perhaps it may merit more space for connecting to others?

Of course you can always have it written along with the original source and "promote" it to its own card later if you feel it's necessary, so you're covered either way. I tend to put the most interesting and surprising ideas into my main box to try to maximize what comes back out of it. If there were 2 more interesting ideas than the definition of cell in that documentary, then I would probably leave the definition with the source and focus on the more important ideas as their own zettels.

As a rule of thumb, for those familiar with Bloom's taxonomy in education, I tend to leave the lower level learning-based notes relating to remembering and understanding as shorter (literature) notes on the source's reference card and use the main cards for the higher levels (apply, analyze, evaluate, create).

Ultimately, time, practice, and experience will help you determine for yourself what is most useful and where. Until you've developed a feel for what works best for you, just write it down somewhere and you can't really go too far wrong.

-

- Mar 2023

-

www.edutopia.org www.edutopia.org

-

Werberger, Raleigh. “Using Old Tech (Not Edtech) to Teach Thinking Skills.” Edutopia (blog), January 28, 2015. https://www.edutopia.org/blog/old-tech-teach-thinking-skills-raleigh-werberger.

link to: https://boffosocko.com/2022/11/05/55811174/ for related suggestion using index cards rather than Post-it Notes.

This process is also a good physical visualization of how Hypothes.is works.

-

-

twitter.com twitter.com

-

<script async src="https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js" charset="utf-8"></script>I do my thinking with pen on paper. Digital tools, even (or especially?) the note-taking ones, are just not for me. <br><br>They may be easy to access or carry around, but what’s the point if they constrain the output?

— Julia Pappas (@JuliaPappasJoy) March 30, 2023A common issue of many digital note taking apps is that while they may have ease for cutting and pasting data into them, moving data around, visualizing it in various forms, and exporting it into a final product may be much more difficult. At the opposite end of the spectrum, physical index cards are much easier to sort, resort, and place into an outline form to create output.

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.comYouTube1

-

Hypothesis Animated Intro, 2013. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QCkm0lL-6lc.

This was an early animation for Hypothes.is as a tool. It was on one of their early homepages and is (still) a pretty good encapsulation of what they do and who they are as a tool for thought.

-

-

mastodon.social mastodon.social

-

Ein Zettel, auf den kein anderer Zettel verweist, ist kein Zettel