reply to u/glugolly at https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/16njtfx/comment/k1l8lyk/?utm_source=reddit&utm_medium=web2x&context=3

How is it that you're defining knowledge management or knowledge management system?

I would argue that any zettelkasten of any stripe is taking knowledge/ideas from either content or one's own brain and transferring them into some sort of media by which they are managed or structured in some way for later linking, combination, or other reuse. By base definition this is clearly knowledge management. I don't know how one defines it otherwise except by pure denial.

Your view of zettelkasten seems remarkably narrow. As a small sample the original Maschinen der Phantasie Marbach exhibition in 2013, which broadly prefigured the popularization of zettelkasten (and in particular the launch of zettelkasten.de) which we see today featured six zettelkasten of which Luhmann's was the only one with reference numbers or what we might now consider explicit HTML-like links. Most of the others contained either explicit groupings or implied links, but that doesn't diminish the value they held for their creators for creating a conversation of ideas for them. Incidentally most of the zettelkasten featured there prefigured Luhmann's and only two were roughly contemporaneous with his.

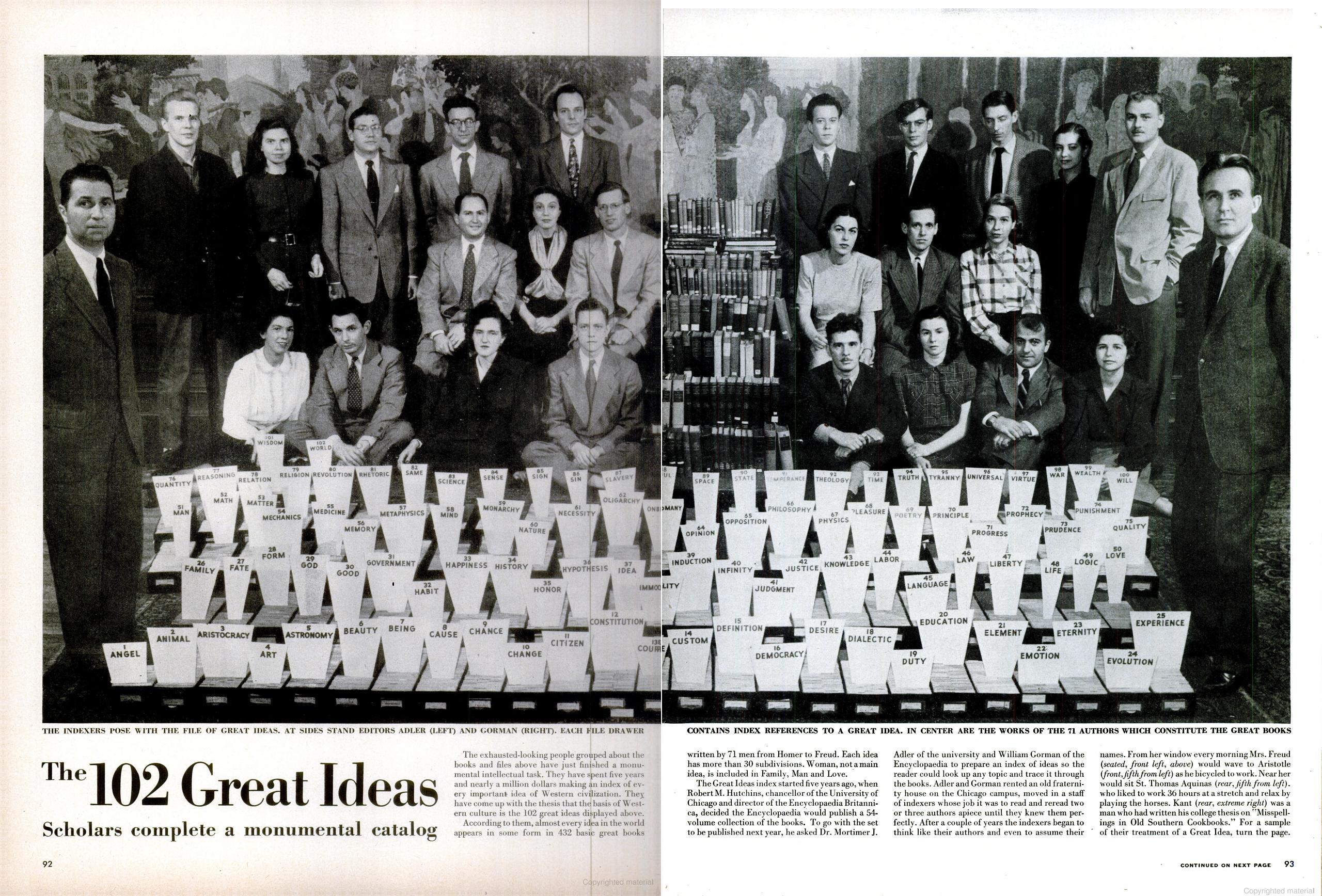

If you look more closely at Adler, et al. you'll notice that the entire purpose of their enterprise was to create and nurture a conversation between themselves and their readers with texts and authors spanning over 2,500 years, a point which is underlined by the introductory volume which preceded the two volumes of the Syntopicon. Not coincidentally, that first volume of the 54 book series was entitled "The Great Conversation."

Specifically from Adler's "How to Read a Book", the first edition of which predated the Great Books of the Western World:

Reading a book should be a conversation between you and the author.

This is a process which is effectuated by

Marking a book is literally an expression of your differences or your agreements with the author. It is the highest respect you can pay him.

and later,

That is to make notes about the shape of the discussion-the discussion that is engaged in by all of the authors, even if unbeknownst to them. For reasons that will become clear in Part Four, we prefer to call such notes dialectical.

(As an aside, why aren't more people talking about the nature of dialectical notes, which seem far more important and useful than either fleeting notes and permanent notes?)

In your link to Holiday, he doesn't say his system isn't a zettelkasten, a word which an English speaker was highly unlikely to have used in 2013 in any case, even when referencing Manfred Kuehn from 2007. It simply indicates that "[Luhmann's] discipline seems to exceed mine because I am a lot less ordered".

The Goitein source (which I wrote) may use commonplace book as a descriptor but that doesn't mitigate the fact that the entirety of the zettelkasten tradition arises from it (the primary difference being things written (usually) on bound pages versus slips of paper). Before these there was the closely related idea of florilegia stemming from the earlier locus communis (Latin) and tópos koinós (Greek).