- Jan 2022

-

-

Placcius recommended considering the first, the second, and the third letters in the words listed in the subject index in order to avoid spending too much time in searching for an entry;

Placcius, De arte excerpendi, 84–5;

-

Just Christoph Udenius, for example, sug-gested leaving thirty or forty blank pages at the end of a commonplace book to be filled in with a well-made subject index, or devoting a separate in-octavo booklet for this essential task;

Just Christoph Udenius, Excerpendi ratio nova (Nordhausen, 1687), 62–3; Placcius, De arte excerpendi, 84–5; Drexel, Aurifodina, 135.

What earlier suggestions might there have been for creating indices for commonplaces?

-

-

stevenson.ucsc.edu stevenson.ucsc.edu

-

I use the end-papers at the back of the book to make a personal index of the author's points in the order of their appearance.

Interesting that he makes no reference to the commonplace book or zettelkasten traditions—particularly because we know he (later?) had an extensive system of index cards.

-

A few friends are better than a thousand acquaintances.

Adler is analogizing friendship to books here.

-

Most of the world's great books are available today, in reprint editions.

Published in 1941, this article precedes the beginning of the project of publishing the Great Books of the Western World for Encyclopedia Britannica, so Adler isn't just writing this from a marketing perspective.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Books_of_the_Western_World

-

-

telepathics.xyz telepathics.xyz

-

What an awesome little site. Sadly no RSS to make it easy to follow, so bookmarking here.

I like that she's titled her posts feed as a "notebook": https://telepathics.xyz/notebook. There's not enough content here (yet) to make a determination that they're using it as a commonplace book though.

Someone in the IndieWeb chat pointed out an awesome implementation of "stories" she's got on her personal site: https://telepathics.xyz/notes/2020/new-york-city-friends-food-sights/

I particularly also like the layout and presentation of her Social Media Links page which has tags for the types of content as well as indicators for which are no longer active.

This makes me wonder if I could use tags on some of my links to provide CSS styling on them to do the same thing for inactive services?

-

-

www.historyofinformation.com www.historyofinformation.com

-

Reflecting upon Robert Darnton's comment, perhaps my personal reading and writing style is more representative of the seventeenth century than the twentieth or twenty-first. Throughout my career in the antiquarian book trade, which began in the 1960s, I found myself moving between subjects in the course of a day as I catalogued various books in stock, read about other books for sale, or discussed the different interests of clients. With access to the Internet in the 1990s it was, of course, possible to follow-up more efficiently on diverse topics with Internet searches and hyperlinks. The way that HistoryofInformation.com is written, as a series of reading and research notes connected by links and indexed in a database, may be viewed to a certain extent as analogous to the method of maintaining and indexing commonplace books described by Locke.

Jeremy Norman, an antiquarian bookseller, indicates that his website is written in much the same manner as John Locke's commonplace book.

-

-

notebook.wesleyac.com notebook.wesleyac.com

-

barnsworthburning.net barnsworthburning.net

-

pluralistic.net pluralistic.net

-

I go through my old posts every day. I know that much – most? – of them are not for the ages. But some of them are good. Some, I think, are great. They define who I am. They're my outboard brain.

Cory Doctorow calls his blog and its archives his "outboard brain".

-

First and foremost, I do it for me. The memex I've created by thinking about and then describing every interesting thing I've encountered is hugely important for how I understand the world. It's the raw material of every novel, article, story and speech I write.

On why Cory Doctorow keeps a digital commonplace book.

-

My composition is greatly aided both 20 years' worth of mnemonic slurry of semi-remembered posts and the ability to search memex.craphound.com (the site where I've mirrored all my Boing Boing posts) easily. A huge, searchable database of decades of thoughts really simplifies the process of synthesis.

Cory Doctorow's commonplace makes it easier to search, quote, and reuse in his process of synthesis.

-

-

www.literature-map.com www.literature-map.com

-

<small><cite class='h-cite via'>ᔥ <span class='p-author h-card'>John Philpin</span> in // John Philpin (<time class='dt-published'>01/05/2022 22:55:00</time>)</cite></small>

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

takingnotenow.blogspot.com takingnotenow.blogspot.com

-

In this spirit he castigated Alexander Harden as "an enemy of the spirit that was fed by a small mind with a large card index," taking up what appears to have been a common criticism of the author, who because of his style that relied overly much on quotations [Die Fackel, Heft 360-62 (1912)].

Some of this critique relates to my classification about the sorts of notes that one takes. Some are more important or valuable than others.

Some are for recall and later memory, some may be collection of ideas, but the highest seems to be linking different ideas and contexts together to create completely new and innovative ideas. If one is simply collecting sententiae and spewing them back out in reasonable contexts, this isn't as powerful as nurturing one's ideas to have sex.

-

-

takingnotenow.blogspot.com takingnotenow.blogspot.com

-

Francis Bacon, for instance, thought that "some books are to be tasted, others to be swallowed and some few to be chewed and digested; that is, some books are to be read only in parts; others to be read, but not curiously; and some few to be read wholly, and with diligence and attention."

An interesting classification of books which fits a fair amount of my own views, particularly looking at the difference between fiction, poetry, and non-fiction.

Source?

-

-

infocult.typepad.com infocult.typepad.com

-

https://infocult.typepad.com/infocult/2020/09/a-book-which-kills.html

A short piece about the book Shadows from the Walls of Death by R. C. Kedzie to highlight arsenic in wallpaper.

-

-

www.newyorker.com www.newyorker.com

-

<small><cite class='h-cite via'>ᔥ <span class='p-author h-card'>Manfred Kuehn</span> in Taking note: Grafton on the Future of Reading (<time class='dt-published'>01/01/2022 12:57:23</time>)</cite></small>

-

If you visit the Web site of the Online Computer Library Center and look at its WorldMap, you can see the numbers of books in public and academic systems around the world. Sixty million Britons have a hundred and sixteen million public-library books at their disposal, while more than 1.1 billion Indians have only thirty-six million. Poverty, in other words, is embodied in lack of print as well as in lack of food. The Internet will do much to redress this imbalance, by providing Western books for non-Western readers. What it will do for non-Western books is less clear.

-

Early English Books Online offers a hundred thousand titles printed between 1475 and 1700. Massive tomes in Latin and the little pamphlets that poured off the presses during the Puritan revolution—schoolbooks, Jacobean tragedies with prompters’ notes, and political pamphlets by Puritan regicides—are all available to anyone in a major library.

-

Chadwyck-Healey and Gale, which sell their collections to libraries and universities for substantial fees.

-

But Google also uses optical character recognition to produce a second version, for its search engine to use, and this double process has some quirks. In a scriptorium lit by the sun, a scribe could mistakenly transcribe a “u” as an “n,” or vice versa. Curiously, the computer makes the same mistake. If you enter qualitas—an important term in medieval philosophy—into Google Book Search, you’ll find almost two thousand appearances. But if you enter “qnalitas” you’ll be rewarded with more than five hundred references that you wouldn’t necessarily have found.

I wonder how much Captcha technology may have helped to remedy this in the intervening years?

-

Scholars well grounded in this regime, like Isaac Casaubon, spun tough, efficient webs of notes around the texts of their books and in their notebooks—hundreds of Casaubon’s books survive—and used them to retrieve information about everything from the religion of Greek tragedy to Jewish burial practices.

What was the form of his system? From where did he learn it? What does it show about the state of the art for his time?

-

Manuals such as Jeremias Drexel’s “Goldmine”—the frontispiece of which showed a scholar taking notes opposite miners digging for literal gold—taught students how to condense and arrange the contents of literature by headings.

Likely from Aurifondina artium et scientiarum omnium excerpendi solerti, omnibus litterarum amantibus monstrata. worldcat

h/t: https://hyp.is/tz3lBmznEeyvEmOX-B5DxQ/infocult.typepad.com/infocult/2007/11/future-reading-.html

Tags

- search

- manuals

- manuscript studies

- publishing

- structural racism

- accessibility

- rare books

- Jeremias Drexel

- Anthony Grafton

- Early English Books Online

- archiving

- institutional racism

- history

- reading practices

- poverty

- Google Books

- Isaac Causaubon

- commonplace books

- Chadwyck-Healey and Gale

- books

- note taking

- transcription errors

- progressive summarization

- examples

Annotators

URL

-

-

takingnotenow.blogspot.com takingnotenow.blogspot.com

-

But this is not the main reason. The other three programs try to achieve the connection or linking between different topics or cards (mainly) by assigning keywords. But this is not what Luhmann's approach recommended. While he did have a register of keywords, this was certainly not the most important way of interconnecting his slips. He linked them by direct references (Verweisungen). Any slip could refer directly to the physical and unchanging location of any other slip.

Niklas Luhmann's zettelkasten had three different forms of links.

- The traditional keyword index/link from the commonplace book tradition

- A parent/child link upon first placing the idea into the system (except when starting a new top level parent)

- A direct link (Verweisungen) to one or more ideas already in the index card catalog.

Many note taking systems are relying on the older commonplace book taxonomies and neglect or forego both of the other two sorts of links. While the second can be safely subsumed as a custom, one-time version of the third, the third version is the sort of link which helps to create a lot of direct value within a note taking system as the generic links between broader topic heading names can be washed out over time as the system grows.

Was this last link type included in Konrad Gessner's version? If not, at what point in time did this more specific direct link evolve?

-

- Dec 2021

-

www.goodreads.com www.goodreads.com

-

That’s it. That’s the only pro I could think of. What were some cons?• From January 1st, 2021, there was a “judge” behind my head, forming impressions and making “hmmmm” and “ummmm” noises when I picked up a book, failed to read on a consistent, schedule, etc.• I felt as though I could not pick up more difficult books and gain from them, as I felt that any longer and/or more difficult book would throw me off my path. I wanted to do some of the classic “Hard Books” ™ in 2021, and that never happened.• I also started to have the completely irrational thought that it somehow “wouldn’t count” toward the challenge if I just picked up and read something that I enjoyed, but that was immensely short. This included most poetry (though I did read some) and most graphic novels (ditto). This is a damn shame, because I would have loved to delve more into both of these genres, and will be doing so a lot more.

You end up optimizing for the thing that you were measuring.

-

-

www.nytimes.com www.nytimes.com

-

Mr. Byers coined a term — “book-wrapt” — to describe the exhilarating comfort of a well-stocked library.

-

-

luhmann.surge.sh luhmann.surge.sh

-

Considering the absence of a systematic order, we must regulate the process of rediscovery of notes, for we cannot rely on our memory of numbers. (The alternation of numbers and alphabetic characters in numbering the slips helps memory and is an optical aid when we search for them, but it is insufficient. Therefore we need a register of keywords that we constantly update.

Luhmann indicated that one must keep a register of keywords to assist in the rediscovery of notes. This had been the standard within the commonplacing tradition for centuries before him. The potential subtle difference is that he seems to place more value on the placement links between cards as well as other specific links between cards over these subject headings.

Is it possible to tell from his system which sets of links were more valuable to him? Were there more of these topical heading links than other non-topical heading links between individual cards?

-

-

boook.link boook.link

-

This looks a lot like Linktree, but for books.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.newyorker.com www.newyorker.com

-

-

Discussion is led by an instructor, but the instructor’s job is not to give the students a more informed understanding of the texts, or to train them in methods of interpretation, which is what would happen in a typical literature- or philosophy-department course. The instructor’s job is to help the students relate the texts to their own lives.

The format of many "great books" courses is to help students relate the texts to their own lives, not to have a better understanding of the books or to hone methods of interpreting them.

This isn't too dissimilar to the way that many Protestants are taught to apply the Bible to their daily lives.

Are students mis-applying the great books because they don't understand their original ideas and context the way many religious people do with the Bible?

-

The idea of the great books emerged at the same time as the modern university. It was promoted by works like Noah Porter’s “Books and Reading: Or What Books Shall I Read and How Shall I Read Them?” (1877) and projects like Charles William Eliot’s fifty-volume Harvard Classics (1909-10). (Porter was president of Yale; Eliot was president of Harvard.) British counterparts included Sir John Lubbock’s “One Hundred Best Books” (1895) and Frederic Farrar’s “Great Books” (1898). None of these was intended for students or scholars. They were for adults who wanted to know what to read for edification and enlightenment, or who wanted to acquire some cultural capital.

Brief history of the "great books".

-

-

thestorygraph.com thestorygraph.com

-

A potential tool to replace Goodreads.

<small><cite class='h-cite via'>ᔥ <span class='p-author h-card'>Kevin Smokler</span> in Kevin Smokler on Twitter: "who else is planning a shift from @goodreads to @thestorygraph in the coming year? Eh, @readandbreathe ?" / Twitter (<time class='dt-published'>12/13/2021 20:39:28</time>)</cite></small>

-

-

-

In fact, the methodical use of notebooks changed the relationship between natural memory and artificial memory, although contemporaries did not immediately realize it. Historical research supports the idea that what was once perceived as a memory aid was now used as secondary memory.18

During the 16th century there was a transition in educational centers from using the natural and artificial memories to the methodical use of notebooks and commonplace books as a secondary memory saved by means of writing.

This allows people in some sense to "forget" what they've read and learned and be surprised by it again later. They allow themselves to create liminal memories which may be refreshed and brought to the center later. Perhaps there is also some benefit in this liminal memory for allowing ideas to steep on the periphery before using them. Perhaps combinatorial creativity happens unconsciously?

Cross reference: learning research by Barbara Oakley and Terry Sejnowski.

-

Commonplaces were no longer repositories of redundancy, but devices for storing knowledge expansion.

With the invention of the index card and atomic, easily moveable information that can be permuted and re-ordered, the idea of commonplacing doesn't simply highlight and repeat the older wise sayings (sententiae), but allows them to become repositories of new and expanding information. We don't just excerpt anymore, but mix the older thoughts with newer thoughts. This evolution creates a Cambrian explosion of ideas that helps to fuel the information overload from the 16th century onward.

-

Simultaneously, there was a revival of the old art of excerpting and the use of commonplace books. Yet, the latter were perceived no longer as memory aids but as true secondary memo-ries. Scholars, in turn, became increasingly aware that to address the informa-tion overload produced by printing, the best solution was to train a card index instead of their own individual consciousness.

Another reason for the downfall of older Western memory traditions is the increased emphasis and focus on the use of commonplaces and commonplace books in the late 1400s onward.

Cross reference the popularity of manuals by Erasmus, Agricola, and Melanchthon.

-

At the beginning of the seventeenth century, the German Jesuit Jeremias Drexel noted that in the celebrated Justus Lipsius, one can find ‘tam copiosa, and illustris eruditio’ (a so abundant and glorious erudition) because the Flemish philosopher not only read many books; he also selected and ex-cerpted the best from them.5

Jeremias Drexel, Aurifodina artium et scientiarum omnium. Excerpendi sollertia, omnibus lit-terarum amantibus monstrata (Antwerp, 1638), 18–19

Tags

- combinatorial creativity

- excerpting

- Melanchthon

- intellectual history

- information management

- second brain

- decline of memory

- Erasmus

- liminal memories

- flâneur

- Jeremias Drexel

- forgetting

- index cards

- art of memory

- erudition

- Cambrian explosion

- cognitive neuroscience

- secondary memory

- learning

- commonplace books

- Terry Sejnowski

- note taking

- Barbara Oakley

- Agricola

- information overload

- Justus Lipsius

- personal knowledge management

Annotators

-

-

publish.obsidian.md publish.obsidian.md

-

https://publish.obsidian.md/danallosso/Bloggish/Actual+Books

I've often heard the phrase, usually in historical settings, "little book" as well and presupposed it to be a diminutive describing the ideas. I appreciate that Dan Allosso points out here that the phrase may describe the book itself and that the fact that it's small means that it can be more easily carried and concealed.

There's also something much more heartwarming about a book as a concealed weapon (from an intellectual perspective) than a gun or knife.

-

-

www.nytimes.com www.nytimes.com

-

“It’s become more and more important as the years went on,” said Marc Resnick, executive editor at St. Martin’s Press. “We learned some hard lessons along the way, which is that a tweet or a post is not necessarily going to sell any books, if it’s not the right person with the right book and the right followers at the right time.”

This seems like common sense to me, why hasn't the industry grokked it?

-

-

twitter.com twitter.com

-

“I could fit this in my pocket,” I thought when the first newly re-designed @parisreview arrived. And sure enough editor Emily Stokes said it’s was made to fit in a “large coat pocket” in the editor’s note.

I've been thinking it for a while, but have needed to write it down for ages---particularly from my experiences with older manuscripts.

In an age of print-on-demand and reflowing text, why in goodness' name don't we have the ability to print almost anything we buy and are going to read in any font size and format we like?

Why couldn't I have a presentation copy sized version of The Paris Review?

Why shouldn't I be able to have everything printed on bible-thin pages of paper for savings in thickness?

Why couldn't my textbooks be printed with massively large margins for writing notes into more easily? Why not interleaved with blank pages even? Particularly near the homework problem sections?

Why can't I have more choice in a range of fonts, book sizes, margin sizes, and covers?

-

-

www.newyorker.com www.newyorker.com

-

Talking about his process, he quoted the jazz pianist Keith Jarrett: “I connect every music-making experience I have, including every day here in the studio, with a great power, and if I do not surrender to it nothing happens.” During our conversations, Strong cited bits of wisdom from Carl Jung, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Karl Ove Knausgaard (he is a “My Struggle” superfan), Robert Duvall, Meryl Streep, Harold Pinter (“The more acute the experience, the less articulate its expression”), the Danish filmmaker Tobias Lindholm, T. S. Eliot, Gustave Flaubert, and old proverbs (“When fishermen cannot go to sea, they mend their nets”). When I noted that he was a sponge for quotations, he turned grave and said, “I’m not a religious person, but I think I’ve concocted my own book of hymns.”

Based on the collection of quotes and proverbs it sounds more like he's got his own commonplace book which he uses to inform his acting process. Sounds almost like he uses them so frequently that he's memorized many of them.

Interesting that he refers to them as "hymns".

Compare this with Eminem's "stacking ammo" for a particular use case.

h/t to Kevin Marks for directing me to this article for this.

-

-

-

From 1676 onward, he follows an excerpting practice that directly refers to Jungius (via one of his students). Regarding Leibniz ’ s Excerpt Cabinet He wrote on slips of paper whatever occurred to him — in part when perusing books, in part during meditation or travel or out on walks — yet he did not let the paper slips (particularly the excerpts) cover each other in a mess; it was his habit to sort through them every now and then.

According to one of his students, Leibniz used his note cabinet both for excerpts that he took from his reading as well as notes an ideas he came up separately from his reading.

Most of the commonplace book tradition consisted of excerpting, but when did note taking practice begin to aggregate de novo notes with commonplaces?

-

It is an important fact that the Bibliotheca Universalis addresses a dual audience with this technology of indexing: on the one hand, it aims at librarians with its extensive and far-reaching bibliography; on the other hand, it goes to didactic lengths to instruct young scholars in the proper organization of their studies, that is, keeping excerpted material in useful order. In this dual aim, the Bibliotheca Universalis unites a scholar ’ s com-munication with library technology, before these directions eventually branch out into the activity of library professionals on the one hand and the private and discreet practices of scholarship on the other hand

Konrad Gessner's Bibliotheca Universalis has two audiences: librarians for it's extensive bibliography and scholars for the instruction of how to properly organize their studies by excerpting material and keeping it in a useful order.

-

Dominicus Nanus did in the Polyanthea

Example of a commonplace book to look into

-

Gessner 1548, fol. 24, following Zedelmaier 1992, p. 88. It is worth noting the fi rst hint about the origin of the German word Kartei : chart books, chartaceos libros , are apparently already in use around 1550.

chart books, cartaceros libros

What are these? Shape/form? Contents?

-

The second volume of the Bibliotheca Universalis , published in 1548 under the title Pandectarum sive Partitionum Universalium , contains a list of keywords, ordered not by authors ’ names, but thematically. This intro-duces a classifi cation of knowledge on the one hand, and on the other hand offers orientation for the novice about patterns and keywords (so-called loci communes ) that help organize knowledge to be acquired.

Konrad Gessner's second edition of Bibliotheca Universalis in 1548 contains a list of keywords (loci communes) thus placing it into the tradition of the commonplace book, but as it is published for use by others, it accelerates the ability for others to find and learn about information in which they may have an interest.

Was there a tradition of published or manuscript commonplace books prior to this?

-

One more thing ought to be explained in advance: why the card index is indeed a paper machine. As we will see, card indexes not only possess all the basic logical elements of the universal discrete machine — they also fi t a strict understanding of theoretical kinematics . The possibility of rear-ranging its elements makes the card index a machine: if changing the position of a slip of paper and subsequently introducing it in another place means shifting other index cards, this process can be described as a chained mechanism. This “ starts moving when force is exerted on one of its movable parts, thus changing its position. What follows is mechanical work taking place under particular conditions. This is what we call a machine . ” 11 The force taking effect is the user ’ s hand. A book lacks this property of free motion, and owing to its rigid form it is not a paper machine.

The mechanical work of moving an index card from one position to another (and potentially changing or modifying links to it in the process) allows us to call card catalogues paper machines. This property is not shared by information stored in codices or scrolls and thus we do not call books paper machines.

Tags

- publishing

- zettelkasten

- librarians

- index cards

- commonplace books

- Conrad Gesner

- Bibliotheca Universalis

- research methods

- links

- catalogs

- note taking

- books

- card catalogs

- Konrad Gessner

- paper machines

- examples

- working in public

- chart books

- information processing

- Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz

- commonplace cabinets

Annotators

-

-

www.amazon.com www.amazon.com

-

aworkinglibrary.com aworkinglibrary.comAbout1

-

I began this site in 2008 in an effort to bring some structure to a long held habit: taking notes about the books I read in a seemingly endless number of notebooks, which then piled up, never to be opened again. I thought a website would make that habit more fruitful and fun, serving as a reference, something the notebooks never did. It did that handily, and more, including making space for me to write and think about adjacent things. More than a dozen years later and this site has become the place where I think, often but not exclusively about books—but then books are a means of listening to the thoughts of others so that you can hear your own thoughts more clearly. Contributions have waxed and waned over the years as life got busy, but I never stopped reading, and I always come back.

Several things to notice here:

- learning in public

- posting knowledge on a personal website as a means of sharing that knowledge with a broader public

- specifically not hiding the work of reading in notebooks which are unlikely to be read by others.

-

- Nov 2021

-

Local file Local file

-

On the other hand, paremiologists seldom specify "definitions"-much less ori- gins-of proverbial expressions that they collect, for the simple reason that so little can be known with certainty.

Paremiology (from Greek παροιμία (paroimía) 'proverb, maxim, saw') is the collection and study of proverbs.

Paremiography is the collection of proverbs.

-

-

www.amazon.com www.amazon.com

-

Indexing Paper: Create Your Own Indexes For The Stuff You Read

https://www.amazon.com/Indexing-Paper-Create-Indexes-Stuff/dp/1926892267/

This really could be quite useful to those with a paper commonplace book or zettelkasten

-

-

www.amazon.com www.amazon.com

-

https://www.amazon.com/Marginalia-Paper-Very-Margin-Notebook/dp/192689202X/

Marginalia Paper, you know, for annotating your own writing...

A must-have for the Hypothes.is fan who wants to go the hipster route.

-

-

www.amazon.com www.amazon.com

-

https://www.amazon.com/Blog-Paper-Advanced-Taking-Technology/dp/1926892100/

Doing some research for my Paper Website / Blog.

Similar to some of the pre-printed commonplace books of old particularly with respect to the tag and tag index sections.

I sort of like that it is done in a way that makes it useful for general life even if one isn't going to use it as a "blog".

How can I design mine to be easily photographed and transferred to an actual blog, particularly with Micropub in mind?

Don't forget space for the blog title and tagline. What else might one put on the front page(s) for identity? Name, photo, address, lost/found info, website URL (naturally)...

Anything else I might want to put in the back besides an category index or a tag index? (Should it have both?)

-

-

site.pennpress.org site.pennpress.org

-

Though firmly rooted in Renaissance culture, Knight's carefully calibrated arguments also push forward to the digital present—engaging with the modern library archives where these works were rebound and remade, and showing how the custodianship of literary artifacts shapes our canons, chronologies, and contemporary interpretative practices.

This passage reminds me of a conversation on 2021-11-16 at Liquid Margins with Will T. Monroe (@willtmonroe) about using Sönke Ahrens' book Smart Notes and Hypothes.is as a structure for getting groups of people (compared to Ahrens' focus on a single person) to do collection, curation, and creation of open education resources (OER).

Here Jeffrey Todd Knight sounds like he's looking at it from the perspective of one (or maybe two) creators in conjunction (curator and binder/publisher) while I'm thinking about expanding behond

This sort of pattern can also be seen in Mortimer J. Adler's group zettelkasten used to create The Great Books of the Western World series as well in larger wiki-based efforts like Wikipedia, so it's not new, but the question is how a teacher (or other leader) can help to better organize a community of creators around making larger works from smaller pieces. Robin DeRosa's example of using OER in the classroom is another example, but there, the process sounded much more difficult and manual.

This is the sort of piece that Vannevar Bush completely missed as a mode of creation and research in his conceptualization of the Memex. Perhaps we need the "Inventiex" as a mode of larger group means of "inventio" using these methods in a digital setting?

-

By examining works by Shakespeare, Spenser, Montaigne, and others, he dispels the notion of literary texts as static or closed, and instead demonstrates how the unsettled conventions of early print culture fostered an idea of books as interactive and malleable.

Jeffrey Todd Knight in Bound to read: Compilations, Collections, and the Making of Renaissance Literature examines the works of various writers to dispel the notion of literary texts as static. He shows how the evolution of early print culture helped to foster the idea as interactive and malleable. This at a time when note takers and writers would have been using commonplacing techniques at even smaller scales for creating their own writing thus creating a similar pattern from the smaller scale to the larger scale.

This pattern of small notes building into larger items with rearrangement which is seen in Carl Linnaeus' index card-based notes as well as his longer articles/writings and publication record over time as well.

-

In Bound to Read, Jeffrey Todd Knight excavates this culture of compilation—of binding and mixing texts, authors, and genres into single volumes—and sheds light on a practice that not only was pervasive but also defined the period's very ways of writing and thinking.

-

In this early period of print, before the introduction of commercial binding, most published literary texts did not stand on shelves in discrete, standardized units. They were issued in loose sheets or temporarily stitched—leaving it to the purchaser or retailer to collect, configure, and bind them.

In the early history of printing, books weren't as we see them now, instead they were issued in loose sheets or with temporary stitching allowing the purchaser or retailer to collect, organize, and bind them. This pattern occurs at a time when one would have been thinking about collecting, writing, and organizing one's notes in a commonplace book or other forms. It is likely a pattern that would have influenced this era of note taking practices, especially among the most literate who were purchasing and using books.

-

This looks interesting with respect to the flows of the history of commonplace books.

Making the Miscellany: Poetry, Print, and the History of the Book in Early Modern England by Megan Heffernan

Tags

- Mortimer J. Adler

- publishing

- Carl Linnaeus

- Wikipedia

- tools for thought

- Smart Notes

- want to read

- inventio

- collective memory

- Great Books of the Western World

- commonplace books

- compilation

- neologisms

- collections

- note taking

- OER

- Vannevar Bush

- Memex

- book binding

- history of the book

- miscellany

- Sönke Ahrens

Annotators

URL

-

-

vimeo.com vimeo.com

-

Reporter John Dickerson talking about his notebook.

While he doesn't mention it, he's capturing the spirit of the commonplace book and the zettelkasten.

[...] I see my job as basically helping people see and to grab ahold of what's going on.

You can decide to do that the minute you sit down to start writing or you can just do it all the time. And by the time you get to writing you have a notebook full of stuff that can be used.

And it's not just about the thing you're writing about at that moment or the question you're going to ask that has to do with that week's event on Face the Nation on Sunday.

If you've been collecting all week long and wondering why a thing happens or making an observation about something and using that as a piece of color to explain the political process to somebody, then you've been doing your work before you ever sat down to do your work.

<div style="padding:56.25% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/169725470?h=778a09c06f&title=0&byline=0&portrait=0" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

Field Notes: Reporter's Notebook from Coudal Partners on Vimeo.

-

-

en.wikipedia.org en.wikipedia.org

-

www.theguardian.com www.theguardian.com

-

Lowering these risks and adapting to those we can no longer avoid will require a mobilisation of resources on the scale of a war economy.

A Good War: Mobilizing Canada for the Climate Emergency by Seth Klein

We did it for the Second World War. We can do it again.

-

-

-

Anything by Chuck Klosterman.

-

I also got into Ayn Rand and George Orwell during the Buckyballs v. The Man days.

-

-

tracydurnell.com tracydurnell.com

-

I’ve been casually looking into WordPress themes designed for news websites since they’re often broken into categories, but haven’t found anything I liked so far.

I haven't had time to look into it yet, but Piper has a custom WordPress theme she's created specifically for commonplace books: https://github.com/piperhaywood/commonplace-wp-theme

-

-

docdrop.org docdrop.org

-

Fromthe sixteenth century we have printed school texts abundantly annotated inthe margins and on interleaved pages with commentary that was likely dic-tated in the classroom and copied over neatly after the fact in the printedbook (fig. 3).

-

Mary Poovey,A History of the Modern Fact: Problems of Knowledge in the Sciences ofWealth and Society(Chicago, 1998).

Most recently, the emergence of the fact has been attributed to methods of commercial recordkeeping (and double-entry bookkeeping in particular).

Reference to read/look into with respect to accounting and note taking.

-

Ciceroalready contrasted the short-lived memoranda of the merchant with the more carefully kept accountbook designed as a permanent record; see Cicero, “Pro Quinto Roscio comoedo oratio,”TheSpeeches,trans. John Henry Freese (Cambridge, Mass., 1930), 2.7, pp. 278–81.

-

The comparison also occurs in GeorgChristoph Lichtenberg, as discussed in Anke te Heesen, “Die doppelte Verzeichnung: Schriftlicheund ra ̈umliche Aneignungsweisen von Natur im 18. Jahrhundert,” inGeha ̈use der Mnemosyne:Architektur als Schriftform der Erinnerung,ed. Harald Tausch (Go ̈ttingen, 2003), pp. 263–86.

-

Y trancis pacon compared one of hisnotebooks to a merchant’s wastebooki see prian ̈ickersW introduction to trancis paconW yrancisuaconX edY ̈ickers SfixfordW ]ggdTW pY xli

Francis Bacon compared one of his notebooks to a merchant's wastebook.

-

was common among early modern authorsW and the notion of the merXchant as a model to imitate persisted through changes to new techniquesY

References to the merchant’s two notebooks as a model for student note taking was common among early modern authors, and the notion of the merchant as a model to imitate persisted through changes to new techniques.

-

acon favored the latter as “of far more profitW and use” Squotedin “tpW” pY ae‘TY

Francis Bacon preferred commonplaces (quotes under topical headings) to adversaria (summaries) as they were "of far more profit, and use".

Note that other references equate these two types of notes: https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/adversaria

-

wn a looser sense the term is also used to designate notes of any kindW as in the tdvY shelfmark inthe qambridge ˆniversity zibrary reserved for books containing marginal annotationsi see ̧illiam vY `hermanW –ohn weem The Politics of Reading and Writing in the xnglish RenaissanceSomherstW ffassYW ]ggcTW ppY dc–ddY

"Adv." (standing for adversaria) is a shelfmark in the Cambridge University Library that is used for books which contain marginal annotations.

-

trancis pacon outlined the two principal methods ofnote taking in a letter of advice to tulke urevilleW who was seeking to hireone or more research assistants in qambridge around ]cggh “ve that shallout of his own ”eading gather [notes] for the use of anotherW must Sas wthinkT do it by spitomeW or obridgmentW or under veads and qommonfllacesY spitomes may also be of ‘ sortsh of any one ortW or part of ynowledgeout of many pooksi or of one pook by itselfY”

Quoted in Vernon F Snow “Ftrancis Bacon's Advice to Fulke Greville on Research Techniques," Huntington Library Quarterly 23, no.4 (1960): 370.

-

wn written cultures material is typically sorted alphabeticallySor by some other method of linguistic ordering such as the number ofstrokes in qhinese charactersTW or systematicallyW according to various sysXtems that strive to map or hierarchize the relations between the items storedSincluding those of uoogle or ffiahooTW or miscellaneouslyY

What about the emergence of non-hierarchal methods? (Can these logically be sorted somehow without this structure?)

With digital commonplacing methods, I find that I can sort and search for things temporally by date and time as well as by tag/heading.

Cross reference:

Tags

- search

- annotations

- interleaved books

- hierarchies

- sorting

- Francis Bacon

- modeling behavior

- pedagogy

- epitome

- abridgment

- discovery

- Cicero

- waste books

- adversaria

- Fulke Greville

- commonplace books

- daybooks

- topical headings

- accounting

- Georg Christoph Lichtenberg

- note taking

- commonplaces

- double-entry accounting

Annotators

URL

-

- Oct 2021

-

-

Jacobean gentleman Henry Peacham wrote in his treatise ‘The Gentleman’s Exercise’ (1612; left) ‘The making of ordinary Lamp blacke. Take a torch or linke, and hold it under the bottome of a latten basen, and as it groweth to be furd and blacke within, strike it with a feather into some shell or other, and grinde it with gumme water.”

I've run across Henry Peacham, the younger, in other contexts and his father within the context of rhetoric and commonplacing.

-

-

www.allwecansave.earth www.allwecansave.earth

-

All We Can Save is a bestselling anthology of writings by 60 women at the forefront of the climate movement who are harnessing truth, courage, and solutions to lead humanity forward.

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

www.youmattermorethanyouthink.com www.youmattermorethanyouthink.com

-

I wrote it because I believe everyone can contribute to the radical transformations we need today.

-

Have we been underestimating our collective capacity for social change?

Recommended by Mark Wagnon

A new way of ‘World Building (Manifesting through Quantum Social Science)

Tags

Annotators

URL

-

-

yishunlai.medium.com yishunlai.medium.com

-

Holiday’s is project-based, or bucket-based.

Ryan Holiday's system is a more traditional commonplace book approach with broad headings which can feel project-based or bucket-based and thus not as flexible or useful to some users.

-

A lot of the literature and shorter articles out there treat many of these systems as recent or "new inventions". Many reference "innovators" like Ryan Holiday or Niklas Luhmann. They patently are not. They've grown out of the Western commonplace book tradition which were traditionally written into books underneath thematic headings (tags/categories in modern digital parlance) until it became cheap enough to mass manufacture Carl Linnaeus' earlier innovation of the index cards in the early 1900s. Then one could more easily rerarrange their ideas with these cards. Luhmann allowed uniquely addressing his cards which made things easier to link. Now there are about thirty different groups working on creating digital tools to do this work, some under the heading of creating "digital gardens".

Often I think it may be easier to go back to some of the books of Erasmus, Melanchthon, or Agricola in the 1500s which described these systems for use in education. Sadly Western culture seems to have lost these traditions and we now find ourselves spending an inordinate amount of time reinventing them.

I'd love to hear your experience in re-introducing it to students in modern educational settings.

-

I’ve been trying for the last year and a half to implement Ryan Holiday’s great index-card filing system for keeping ideas in place.

I don't like the common framing I see in posts like this that want to credit a particular person for "inventing" a pattern like these that goes back centuries. The fact that we've lost these patterns is a terrible travesty.

-

I’m not going to post them at this point in this post, because I want to save you from my experience: I spent three hours one day watching videos and reading links and posting on message boards and reading the replies, and that doesn’t include the year and a half I spent half-heartedly trying to understand the system. I’ll also only post the links that really made sense to me.

It shouldn't take people hours a day with multiple posts, message boards, reading replies, and excessive research to implement a commonplace book. Herein lies a major problem with these systems. They require a reasonable user manual.

One of the reasons I like the idea of public digital gardens is that one can see directly how others are using the space in a more direct and active way. You can see a system in active use and figure out which parts do or don't work or resonate with you.

-

Weirdly, in the master of fine arts classes I’ve taught so far, there’s never been a single class on how to store and access your research.

The fact that there generally aren't courses in high school or college about how to better store and access one's research is a travesty. I feel like there are study skills classes, but they seem to be geared toward strategies and not implemented solutions.

-

-

bildung.royscholten.nl bildung.royscholten.nl

-

What I'm interested in is doing this with visual artefacts as source material. What does visual pkm look like? Journaling, scrapbooking, collecting and the like. The most obvious tool is the sketchbook. How does a sketchbook work?

It builds on many of these traditions, but there is a rather sizeable movement in the physical world as well as lots online of sketchnotes which might fit the bill for you Roy.

The canonical book/textbook for the space seems to be Sketchnote Handbook, The: the illustrated guide to visual note taking by Mike Rohde.

For a solid overview of the idea in about 30 minutes, I found this to be a useful video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=evLCAYlx4Kw

-

-

www.hylo.com www.hylo.comHylo1

-

Ministry for the Future

The Amazon product page for the book, Ministry for the Future, quotes Ezra Klein.

If I could get policymakers, and citizens, everywhere to read just one book this year, it would be Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Ministry for the Future.

-

-

charleseisenstein.org charleseisenstein.org

-

The More Beautiful World Our Hearts Know Is Possible

-

-

www.springer.com www.springer.com

-

A Fuller Explanation

-

-

www.penguinrandomhouse.com www.penguinrandomhouse.com

-

Who Really Feeds the World?

-

-

www.penguinrandomhouse.com www.penguinrandomhouse.com

-

Earth Democracy

-

-

www.kentuckypress.com www.kentuckypress.com

-

The Violence of the Green Revolution

-

-

medium.com medium.com

-

First, set clear goals and prioritize among conflicting goals (for instance, price to maximize revenue but ensure a 10 percent profit increase).Second, pick one of the three types of pricing strategies: maximization, skimming, or penetration.Third, set price-setting principles that define the rules of your monetization models, price differentiation, price endings, price floors, and price increases.Finally, define your promotional and competitive reaction principles to avoid knee-jerk price reactions.

Il documento di [[Strategia di monetizzazione]] dovrebbe essere costruito su 4 blocchi:

- Avere obiettivi chiari e messi in priorità tra loro, specialmente tra gli obiettivi in conflitto;

- Prendere una decisione riguardo una delle strategie di prezzo tra: massimizzazione, skimming o penetrazione;

- Stabilire dei principi che determinino le regole riguardo i modelli di monetizzazione, la differenziazione di prezzo ecc;

- Definire pattern di prezzo in reazione ai competitor e di promozione, per evitare di fare errori;

-

A pricing strategy is your short- and long-term monetization plan. The best companies document their pricing strategies and make it a living and breathing document.

È importante delineare una #[[Strategia di monetizzazione]] che sia a breve termine, come a lungo termine. Tale documento raccoglie le diverse strategie di pricing e deve essere costantemente aggiornato e monitorato.

-

What monetization model do we envision for our new product? Why is it the right one, and how did we choose it?Which models did we not pick, and why?What are the most important trends in our industry? How do they affect our choice of a monetization model? How do we plan to monetize our product if customer usage varies significantly? Which price structures have we considered and why?Do we have the right capabilities and infrastructure to execute the chosen monetization model and price structure?

Queste sono domande che il CEO dovrebbe porsi riguardo la scelta del modello di #pricing

-

To have a chance at converting free customers to paid customers, you need to test what benefits they will pay for and ensure a functional free experience. You also need to know exactly how many customers will actually be willing to pay. What’s more, you must avoid giving the farm away for free because it will leave your premium offering with very little value.

Nel caso del #pricing #freemium è importante considerare che l'obiettivo è quello di convertire le persone free in persone paganti. Per farlo è necessario però capire quali sono i benefici per cui queste persone sono disposte a pagare, bisogna anche evitare di dare via tutto gratis togliendo valore alla nostra offerta premium.

-

Customers pay when they use or benefit from the product. This can be exceptionally successful if you can align the metric directly to how customers perceive value. This can be effective if you are adept at predicting future trends. The alternative pricing model makes sense when your innovation creates significant value to end customers but you cannot capture a fair share of that value using traditional monetization models.

Il modello di pricing del #[[alternate metric]] si applica quando i clienti pagano se usano effettivamente il prodotto. Questo tipo di modello ha senso solo se il tuo prodotto genera un'innovazione tale che non riesci a trovare un modello di #pricing adatto

-

Auctions — competition based pricing for goods and services. Google AdWords, eBay, and other two-sided marketplaces use auctions. Market determines price. If you can control inventory for an in demand product, you should consider this model.

Il modello delle #aste è un modello in cui il mercato determina il prezzo di un bene. Se si è in controllo di un prodotto per cui c'è tanta richiesta, allora bisogna considerare questo modello.

-

Dynamic pricing — airline industries, Uber offer dynamic pricing for peak demand times. Dynamic pricing boosts the monetization of fixed and constrained capacity. Complex model requiring extensive data analytics.

Il modello del #[[pricing dinamico]] è il modello tipico di Uber e delle linee aeree. Questo modello migliora le vendite di disponibilità limitate e fisse. Si tratta di un modello complesso, richiede tanti dati ed analisi.

-

Subscription —recurring revenue increases customer lifetime revenue, revenue predictability, cross-sell and upselling opportunities. Works well in online and offline services where the product is used continually, in competitive industries, and where it can reduce barriers to entry through large upfront payments.

In che casi ha senso utilizzare un modello di pricing basato su #abbonamento ?

Quando si sceglie questa opzione ci si ritrova in una situazione in cui gli acquisti ricorrenti aumentano il #[[lifetime value]] dei clienti, inoltre è possibile stimare delle previsioni di vendita proprio a causa dei pagamenti ricorrenti, ci sono tante opportunità di #cros-sell e di #upsell.

È un sistema adatto sia ai servizi online che offline ma la condizione è che il prodotto venga usato continuamente ed inoltre è ottimale nelle situazioni in cui riduce le barriere all'entrata tramite un grande pagamento in anticipo.

-

What are the product configuration/bundles we plan to offer? Why did we pick these offers? Do they align with our key segments? If not, why not?What are the leader, filler, and killer features for the new product or service our company is developing? How did we find out?Have we explored a good/better/best approach to product configuration and bundling? What do we expect sales to be for each product configuration? Is the share of the basic product configuration lower than 50 percent? If not, why not?Have we explored bundling our new product with existing products? What would be the benefits for us and the customers?Have we considered unbundling as an opportunity? What would be the benefits to customers and our business (if any)?

Queste sono le domande che un CEO dovrebbe porsi riguardo i bundle di prodotto:

- Quali sono i bundle che abbiamo deciso di offrire? A che prezzo? Queste offerte si allineano con i segmenti individuati?

- Quali sono le caratteristiche leader, filler e killer di questo bundle? Come le abbiamo scoperte?

- Quali sono le opzioni bene/meglio e top per questo bundle? Quali ci aspettiamo siano le vendite per ogni bundle? La condivisione della configurazione base del prodotto è al di sotto del 50%? Se no, perché?

- Abbiamo ipotizzato di creare bundle di prodotto con altri prodotti? Quali sarebbero i benefici nostri e dei clienti?

- Abbiamo considerato l'ipotesi di smantellare il bundle? Quali sarebbero i vantaggi per noi e per i clienti?

-

Align offers with segmentsDon’t go beyond nine benefits or four productsCreate win-win bundles for you and the customerDon’t give away too much in the entry-level product. Look at customer distribution by product and upsell percentage to qualify a problemHard bundles might not work and an a la carte bundle may be betterPer product pricing needs to be higher than bundled pricingMessaging and communicating the value of the bundle is a sales opportunity depending on what product or feature they are afterBundle an integrated experience and charge a premium instead of a discountDon’t bundle for the sake of bundlingLook for inverse correlations and exploit both by including the nice to have inverse.

Questi sono alcuni dei consigli che bisogna considerare nella creazione di configurazioni di prodotto diverse.

- Allineare l'offerta ai segmenti;

- Non andare oltre i 9 benefits o i 4 prodotti;

- Crea bundle che siano vittoria per te e per i consumatori;

- Non dare troppo valore nel prodotto di entrata, guarda la distribuzione dei clienti per prodotto e fai upsell in percentuale, così da qualificare il problema;

- I bundle fissi potrebbero non funzionare, quelli personalizzati invece si;

- Il prezzo per singolo prodotto deve essere più alto di quello in bundle;

- Comunicare il valore del bundle può essere una opportunità di vendita a seconda di quale prodotto si sta cercando di vendere;

- Crea un'esperienza premium riguardo il tuo prodotto e dalle un prezzo premium, invece che un prezzo scontato;

- Non creare bundle semplicemente per lo sfizio;

- Cerca correlazioni inverse includendo l'opposto delle feature nice to have;

-

Establishing which features are leaders (must-haves), fillers (nice-to-haves), and killers (features that are deal killers), andCreating good/better/best options.

Due sono gli aspetti principali di una configurazione di prodotto efficace:

- Bisogna stabilire le caratteristiche leader (must have), filler (nice to have) e killer

- Bisogna creare delle opzioni di prodotto che siano buone, migliori, top

-

Product configuration and bundling are your key building blocks for designing the right products for the right segments at the right price points. Product configuration is about putting the appropriate features and functionality — those customers need, value, and are willing to pay for — into the product; this process has to be done for each identified segment. Systematic product configuration prevents you from loading too many features into a product and producing a feature shock.

Un prodotto deve essere creato configurando le giuste caratteristiche in dei bundle che rispettino i determinati segmenti che abbiamo individuato. Ogni configurazione di prodotto deve rispettare i determinati bisogni, valori e WTP dei segmenti.

-

Does our product development team have serious pricing discussions with customers in the early stages of the new product’s development process? If not, why not?What data do we have to show there’s a viable market that can and will pay for our new product?Do we know our market’s WTP range for our product concept? Do we know what price range the market considers acceptable? What’s considered expensive? How did we find out?Do we know what features customers truly value and are willing to pay for, and which ones they don’t and won’t? And have we killed or added to the features as a consequence of this data? If not, why not?What are our product’s differentiating features versus competitors’ features? How much do customers value our features over the competition’s features?

Queste sono valutazioni che deve fare il CEO riguardo il #pricing del prodotto da lui creato.

Tra le valutazioni e domande da porsi ci sono:

- Il team rivolto al prodotto ha avuto una seria discussione riguardo il #pricing? Se no, perché non è accaduto?

- Quali dati abbiamo che indicano che c'è un mercato che può e vuole pagare per questo prodotto?

- Conosciamo il range di #WTP del nostro concetto di prodotto? Sappiamo il nostro target quali prezzi ritiene accettabili, esagerati ed immotivati? Come lo abbiamo scoperto?

- Sappiamo quali caratteristiche del prodotto hanno maggiore valore agli occhi dei consumatori, quali sono disposti a pagare e quali invece non hanno alcun valore? Se no, perché?

- Quali sono le caratteristiche del nostro prodotto che sono elemento di #differenziazione rispetto ai prodotti dei nostri competitor? Quanto valore hanno queste caratteristiche agli occhi dei consumatori?

-

Did we segment before we designed the product? If not, why not?What were the segments? How did we get to these? Which ones would we serve initially? Do they represent a sizable market?What criteria were they based on? How different are these segments in their WTP? Can we respond differently to each segment? If so, how?How did we describe the segments? What observable criteria do we have in these descriptions? Do our descriptions and observable criteria on each segment pass our sales team’s sniff test?How many segmentation schemes do we have in our company? Can we consolidate to one segmentation across product, marketing, and sales?Who in our company is responsible for segmentation? At what point in the innovation cycle does this person (or people) get involved?

Queste sono le domande che un CEO dovrebbe porsi riguardo la segmentazione per la creazione di un prodotto.

- Abbiamo fatto una segmentazione prima di creare il prodotto? Se no perché?

- Quali sono i segmenti che abbiamo individuato, in che modo ci siamo arrivati, quale abbiamo deciso di servire inizialmente, rappresentano un mercato sostenibile?

- In funzione di quale criterio sono distinti i segmenti? In che modo cambia la #WTF dei differenti segmenti? Possiamo rispondere diversamente ad ogni segmento?

- In che modo descriviamo i segmenti? Quali sono i criteri osservabili che abbiamo in queste descrizioni?

- Quanti schemi di segmentazione abbiamo? Riusciamo a consolidare su un solo segmento tutte le nostre energie aziendali?

- Chi è il responsabile della segmentazione? In che momento interviene?

-

Do Segmentation Right:Begin with WTP data — By clustering individuals according to their WTP, value, and needs data, you will discover your segments — groups of people whose needs, value, and willingness to pay differ.Use common sense — Practicality and common sense are as important as statistical indicators.Create fewer segments, not more — Serving each new segment adds significant complexity for sales, marketing, product and service development, and other functions. Smart companies start with a few segments — three to four — and then expand gradually until they reach the optimal number.Don’t try to serve every segment — The products and services you develop should match your company’s overall financial and commercial goals. A segment must deliver enough customers — and enough money — to make the investment worthwhile.Describe segments in detail in order to address them — Investigate whether each segment has observable criteria for customizing your sales and marketing messages to them.

Come si può segmentare in maniera efficace?

- Si comincia con i dati emersi dall'analisi sul #WTP, si creano cluster di individui in funzione di WTP, valori e bisogni, così emergono dei segmenti;

- Punta a pochi segmenti, non molti, ogni segmento porta con sé entropia che deve essere gestita, il numero ideale di segmenti è 3-4 e poi ci si espande in maniera graduale fino a raggiungere il numero ottimale;

- Non devi servire ogni segmento, il prodotto che crei dovrebbe essere coerente con gli obiettivi generali ed economici della tua azienda. Un segmento deve essere visto come un investimento;

- Descrivi ogni segmento in dettaglio e cerca criteri evidenti nel comportamento del segmento per poter customizzare il più possibile;

-

The message here is clear: You need to create segments in order to design highly attractive products for each segment. And you must base your segmentation on customers’ needs, value, and WTP. This way, segmentation becomes a driver of product design and development, not an afterthought.

Quale è il modo migliore per definire le caratteristiche migliori di un prodotto?

Bisogna analizzare il mercato e segmentare i bisogni, valori e WTP dei consumatori. In questo modo la segmentazione diventa la guida della creazione del prodotto.

-

New products fail for many reasons. But the root of all innovation evil is the failure to put the customer’s willingness to pay for a new product at the very core of product design.

Quale è una delle prime cose che si deve valutare nell'elaborazione di un prezzo per un prodotto?

Una dele prime cose da valutare è la volontà di pagare per il nuovo prodotto in questione da parte dei consumatori, questa deve essere messa al centro del processo di creazione del nuovo prodotto.

-

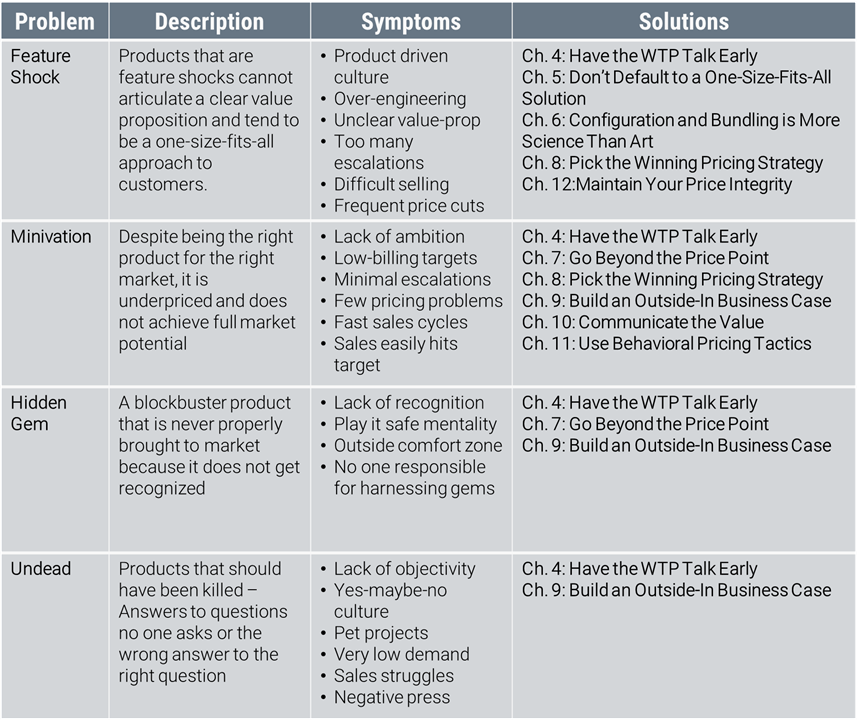

Startup companies are much more likely to possess Feature Shock and Undead pricing problems. However, some product launches are treated as Minivations and startup companies with Hidden Gem technology may not see the need for a pivot. Regardless of the problem you may encounter, there are certain things you can do to find the solution.

Quelli mostrati nella tabella sono i 4 tipi di problemi in termini di #pricing che si possono incontrare nella creazione di un prodotto.

Quelli mostrati nella tabella sono i 4 tipi di problemi in termini di #pricing che si possono incontrare nella creazione di un prodotto.Tra i problemi che si verificano più di frequente nelle startup abbiamo il fenomeno del #featureshock oppure dell' #undead

-

Feature shocks happen when you try to cram too many features into one product, creating a confusing and often expensive mess. In a sincere effort to have it be “all things to all people,” you launch a product that pleases few. The result is the product’s value is less than the sum of the parts. Due to its multitude of features — none of them a standout — these products are costly to make, overengineered, hard to explain, and usually overpriced.

Si ha un problema di #featureshock nel momento in cui si cerca di inserire troppe funzioni all'interno di un prodotto.

Così facendo si incorre nella situazione in cui cercando una soluzione "unica per tutti" si crea una soluzione che accontenta nessuno ed il cui valore è inferiore al valore delle sue singole parti. In questo modo tutte le caratteristiche si annullano tra loro e ci si ritrova con un prodotto che inoltre è nella maggior parte dei casi:

- costoso da creare;

- complicato da creare;

- difficile da spiegare;

- troppo costoso da acquistare

-

No one wants to sell his or her idea short. Minivations are products that tap neither a product concept’s full market potential nor its full price potential. Companies that fall into the minivation trap underexploit the market opportunity and the price they could have charged, thereby robbing themselves of profits. Minivations go down as undermonetized products cursed with a “what might have been” tag.

Il caso del problema di #minivation è quello in cui il prodotto non raggiunge né il massimo del potenziale di mercato né il massimo del potenziale di prezzo. Le aziende che cadono in questa trappola sono aziende che danno al proprio prodotto un prezzo più basso di quanto sia effettivamente il suo valore ed in questo modo rinunciano a dei guadagni.

-

With a hidden gem product, a company has a brilliant, even revolutionary idea but fails to both recognize it and quantify the product’s value to customers. Or the company decides it lacks the capabilities to bring the unusual idea to market. Hidden gems often end up in limbo, neither launched nor killed. They often don’t make it to market, but if they do, they arrive undervalued, as freebies or deal sweeteners.

Ci si ritrova in un caso di #hiddengem quando si ha un'idea innovativa, addirittura rivoluzionaria, ma non si riesce a riconoscere sia la portata di impatto dell'idea sia a darle il giusto valore.

In questo modo ci si ritrova con trascurare l'idea non riuscendo mai a portarla sul mercato, oppure si decide in maniera volontaria di non farla evolvere mai.

-

Applied to monetizing innovation, an undead product is one that still exists in the marketplace, but demand is virtually nonexistent. The product, for all intents and purposes, is dead, yet it continues to “walk around” like a zombie.

Un prodotto #undead è semplicemente un prodotto che ancora infesta il mercato ma che ha una richiesta quasi inesistente.

-

When an undead is in the making, you become delusional and detest any evidence that goes against your beliefs. You resist objectivity and keep investing time, feeling you have come too far. Once the product is in the market, your sales teams can’t sell it, and it causes them to miss their targets — by a lot.

In che modo si può capire se ci si ritrova a lavorare con un prodotto #undead ?

Si può capire che ci si ritrova con un prodotto di questo tipo se si diviene sempre più illusi riguardo il prodotto e si odia e disprezza ogni prova che vada contro le proprie convinzioni.

Si cerca di resistere all'oggettività e si continua ad investire tempo, emozioni ed altre risorse. Una volta che il prodotto è poi sul mercato il team sales e marketing non riescono a piazzarlo né farci alcuna vendita, spesso sbagliando il target.

-

Myth #1: If you simply build a great new product, customers will pay fair value for it. “Build it, and they will come” is the mantra. Why we believe it: because Star Wars, FedEx, Harry Potter were all rejected by directors, businessmen, and editors and were wild successes. But they are the exceptions not the rule.Myth #2: The new product or service must be controlled entirely by the innovation team working in isolation. Why we believe it: because Henry Ford said that customers would have wanted a faster horse. Indeed, the Innovators Dilemma, Different, Play Bigger, etc. put a premium on this as well. The fine line that must be walked is that of being different in a way that we are confident will resonate with customers. Confident because you have talked, consulted, argued, and shown the product to customers and more importantly, gauged their willingness to pay.Myth #3: High failure rate of innovation is normal and is even necessary. Why we believe it: sports analogies.Myth #4: Customers must experience a new product before they can say how much they’ll pay for it. Why we believe it: because its safe.Myth #5: Until the business knows precisely what it’s building, it cannot possibly assess what it is worth. Why we believe it: a cost-plus mindset that ties willingness to pay with what it cost us to build.

Ci sono alcuni miti riguardo l'elaborazione del #pricing.

-

The most important aspect of moving to a “design the product around the price” innovation process is finding out as early as you can whether customers value your innovation and would pay for it. You can only determine customers’ WTP by actually asking them — not by imagining what they will say.Two pieces of information are important in this phase: customers’ overall WTP for a product (the price range they have in mind) and their WTP for each feature (so you know which features matter most and which features don’t matter at all).Five types of research questions will help you get these answers. Best practices in having these discussions include positioning them as “value talks” (not as pricing discussions), expecting key insights to come from the simplest questions, mixing structured with unstructured questions, and not relying solely on quantitative data.

La valutazione della volontà di pagamento da parte dei clienti è una delle valutazioni più importanti da fare quando si decide il prezzo di un prodotto. Ci riferiamo ad essa con #WTP.

Dei 4 problemi di #pricing discussi in questo libro, una #WTP effettuata nelle fasi iniziali del progetto è determinante e capace di evitare il manifestarsi di TUTTI I PROBLEMI DI PREZZO.

Per poter capire questa #WTP è essenzialmente necessario se effettivamente i consumatori danno valore al tuo prodotto oppure no, un valore economico, si intende.

-

Direct, purchase probability: “what do you think could be an acceptable price?” “What do you think would be an expensive price?” “What do you think would be a prohibitively expensive price?” “Would you buy this product at $?”Purchase probability questions: “On a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 is, I would never buy this product and 5 is, I would most definitely buy this prdouct, how would you rate this product?” 4 or 5 you stop. Less than 3 lower the price and try again.Most–least: create a subset of your features and ask them to rank the features from most valuable to least. Change the subset for 5 different sets. You will end up with rich feature by feature feedback.Build-your-own: give them a list of features and ask them to build their “ideal product.” As they add features, the price increases. See where they stop with features and price.Purchase simulations: A.K.A Conjoint analysis. This is where you test the pricing of certain bundles of features. Changing bundles and prices. Definitely the most complex option and usually requires software and/or a consultant to manage. As expected, however, the results can be game changing.

Questo è un framework che si può utilizzare per stabilire la #WTP riguardo un prodotto.

- Fare domande di questo tipo, volte a verificare la probabilità di acquisto in maniera diretta:

- Quanto pensi possa essere un prezzo accettabile per questo prodotto?

- Quanto pensi possa essere un prezzo esagerato per questo prodotto?

- Quanto pensi possa essere un prezzo proibitivo per questo prodotto?

- Compreresti questo prodotto alla cifra di..?

- Domande volte a verificare la probabilità di acquisto in maniera indiretta:

- Su una scala da 1 a 5, dove 1 è "Non comprerei mai questo prodotto" e 5 è "Lo comprerei sicuramente" che voto daresti a questo prodotto? Se il voto è <= di 3 abbassa il prezzo e riprova;

- Crea un gruppo di feature del prodotto e chiedi alle persone di metterle in ordine dalla più valida alla meno valida, usa 5 gruppi di caratteristiche;

- Dai una lista delle caratteristiche alle persone e chiedigli di creare il loro "prodotto ideale" con le caratteristiche che gli hai fornito, ad ogni caratteristica aggiunta aumenta il prezzo, vedi dove si fermano nel processo di aggiunta;

- Testa diverse configurazioni di caratteristiche, cambiando configurazione e prezzo, di solito questo test richiede software o consulenti per poter essere effettuato, i risultati però sono validissimi.

-

-

www.youtube.com www.youtube.com

-

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zjZAdPX6ek0

Osculatory targets or plaques were created on pages to give priests

Most modern people don't touch or kiss their books this way and we're often taught not to touch or write in our texts. Digital screen culture is giving us a new tactile touching with our digital texts that we haven't had since the time of the manuscript.

-

- Sep 2021

-

www.academia.edu www.academia.edu

-

tracydurnell.com tracydurnell.com

-

I think it’s valuable to add some initial thinking and reflection when I bookmark an article or finish reading a book, but haven’t yet figured out a process for revisiting recent notes to find connections and turn that into longer or more complex thought.

This is definitely the harder part of the practice, but daily, weekly, monthly, quarterly, and annual reviews can definitely help.

To start I primarily focused on 3-5 broader sub-topics of things I felt were most important to me and always did those first. This helps to begin aggregating things and making a bigger difference. The rest of my smaller "fleeting" notes I didn't worry so much about and left to either come back to later or just allow them to sit there.

I think Sonke Ahrens' book How to Take Smart Notes was fairly helpful in laying this out.

Incidentally the spaced repetition of review is also good for your memory of the things you find important.

-

-

s3.us-central-1.wasabisys.com s3.us-central-1.wasabisys.com

-

I love this outline/syllabus for creating a commonplace book (as a potential replacement for a term paper).

I'd be curious to see those who are using Hypothes.is as a communal reading tool in coursework utilize this outline (or similar ones) in combination with their annotation practices.

Curating one's annotations and placing them into a commonplace book or zettelkasten would be a fantastic rhetorical exercise to extend the value of one's notes and ideas.

-

For example, I will be keeping my own Commonplace Book this semester, and because of my particular research interests I may include headings such as “Cosmetics,” “Perfume,” “Odors,” and “Cannibalism.”

Based on these headings, I think it would be quite interesting to read her commonplace, but I suspect the heading Cannibalism is a sly side-reference to Montaigne's own "Des cannibales".

-

Public link to the document: https://docdrop.org/pdf/Creating-a-Commonplace-Book---Kennedy-Colleen-E_-0r3r1.pdf/

-

I will be looking for your conscious choice in your entry selections, dedicated organizational patterns and curation techniques, self-reflection and thoughtful responses in your short writing exercises, and as a whole, your engagement with and understanding of our various texts.

Focus on some of the conscious choices, organization and curation are pieces missing from modern digital note taking space in talking about digital gardens and zettelkasten.

-

Please include only quotations, and a brief bibliographic reference. Do not add commentary explaining why you like or chose a particular quotation. (e.g. Hieronimo in The Spanish Tragedy 3.2.1-15, or Kyd, The Spanish Tragedy 3.2.1-15,or evenas simple asThe Spanish Tragedy 3.2.1-15).

She's a bit over-prescriptive here in terms of the form a commonplace book should contain. In particular, she seems to be holding to the form up to the 17th Century. Personally in a classroom exercise, I wouldn't include this particular limitation.

-

☞An index(the final pages of the Commonplace Book) of at least 20 words. The index will be listed alphabetically (or thematically, then alphabetically) by your commonplace book headings with page numbers. You may decide to also add cross-references to authors, other frequently appearing terms that were not heading chapters, etc. (Figure 9)

One might also suggest the use of John Locke's method here: See: https://publicdomainreview.org/collection/john-lockes-method-for-common-place-books-1685

-

☞(excerpts) Beal, Peter. Dictionary of English Manuscript Terminology: 1450 to 2000.Oxford, GB: OUP Oxford, 2007. ProQuest ebrary. Web. 19 December 2016.☞Lesser, Zachary and Peter Stallybrass. “The First Literary Hamlet and the Commonplacing of Professional Plays.” Shakespeare Quarterly, (2008), 371–420.☞Smyth, Adam. “Commonplace Book Culture: A List of Sixteen Traits.” Women and Writing, c.1340-c.1650: The Domestication of Print Culture. Manuscript Culture in the British Isles. Eds. Lawrence-Mathers, A. and Hardman, P. Rochester, U.S.: Boydell and Brewer, 90-110.☞Summers, David. “—the proverb is something musty: The Commonplace and Epistemic Crisis in Hamlet.”Hamlet Studies 20.1-2(1998): 9-34.

sources to add to my reading list, if not already there

-