https://www.reddit.com/r/Zettelkasten/comments/zl2hwh/is_the_concept_of_personal_knowledge_management/

This essay seems to be more about shiny object syndrome. The writer doesn't seem to realize any problems they've created. Way too much digging into tools and processes. Note the switching and trying out dozens of applications. (Dear god, why??!!) Also looks like a lot of collecting digitally for no clear goal. As a result of this sort of process it appears that many of the usual affordances were completely blocked, unrealized, and thus useless.

No clear goal in mind for anything other than a nebulous being "better".

One goal was to "retain what I read", but nothing was actively used toward this stated goal. Notes can help a little, but one would need mnemonic methods and possibly spaced repetition neither of which was mentioned.

A list of specific building blocks within the methods and expected outcomes would have helped this person (and likely others), but to my knowledge this doesn't exist as a thing yet though bits and pieces are obviously floating around.<br />

TK: building blocks of note taking

Evidence here for what we'll call the "perfect system fallacy", an illness which often goes hand in hand with "shiny object syndrome".

Too many systems bound together will create so much immediate complexity that there isn't any chance for future complexity or emergence as the proximal system is doomed to failure. One should instead strive for immediate and excessive simplicity which might then build with time, use, and practice into something more rich and complex. This idea seems to be either completely missed or lost in the online literature and especially the blogosphere and social media.

people had come up with solutions

Sadly, despite thousands of variations on some patterns, people don't seem to be able to settle on either "one solution" or their "own solution" and in trying to do everything all at once they become lost, set adrift, and lose focus on any particular thing they've got as their own goal.

In this particular instance, "retaining what they read" was totally ignored. Worse, they didn't seem to ever review over their notes of what they read.

I was pondering about different note types, fleeting, permanent, different organisational systems, hierarchical, non-hierarchical, you know the deal.

Why worry about all the types of notes?! This is the problem with these multi-various definitions and types. They end up confusing people without giving them clear cut use cases and methods by which to use them. They get lost in definitional overload and aren't connecting the names with actual use cases and affordances.

I often felt lost about what to takes notes on and what not to take notes on.

Why? Most sources seem to have reasonable guidance on this. Make notes on things that interest you, things which surprise you.

They seem to have gotten lost in all the other moving pieces. Perhaps advice on this should come first, again in the middle, and a third time at the end of these processes.

I'm curious how deeply they read sources and which sources they read to come to these conclusions? Did they read a lot of one page blog posts with summarizations or did they read book length works by Ahrens, Forte, Allosso, Scheper, et al? Or did they read all of these and watch lots of crazy videos as well. Doing it "all" will likely lead into the shiny object syndrome as well.

This seems to outline a list of specifically what not to do and how not to approach these systems and "popular" blog posts that are an inch deep and a mile wide rather than some which have more depth.

Worst of all, I spent so much time taking notes and figuring out a personal knowledge management system that I neglected the things I actually wanted to learn about. And even though I kind of always knew this, I kept falling into the same trap.

Definitely a symptom of shiny object syndrome!

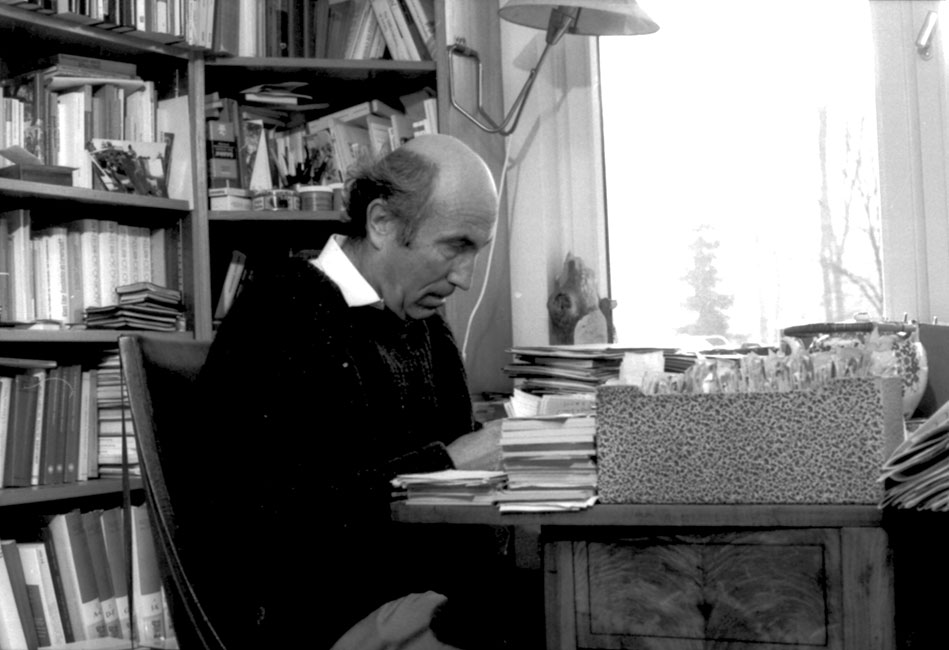

Luhmann zuhause am Zettelkasten (vermutlich Ende der 1970er/Anfang 1980er Jahre)<br />

Copyright Michael Wiegert-Wegener<br />

via

Luhmann zuhause am Zettelkasten (vermutlich Ende der 1970er/Anfang 1980er Jahre)<br />

Copyright Michael Wiegert-Wegener<br />

via  (via

(via